Abstract

Nanoscale systems have increasingly been used in biomedical applications, enhancing the demand for the development of biomolecule-functionalized nanoparticles for targeted applications. Such designer nanosystems hold great prospective to refine disease diagnosis and treatment. To completely investigate their potential for bioapplications, nanoparticles must be biocompatible and targetable toward explicit receptors to guarantee particular detecting, imaging, and medication conveyance in complex organic milieus, for example, living cells, tissues, and organisms. We present recent works that explore enhanced biocompatibility and biorecognition of nanoparticles functionalized with DNA and different DNA entities such as aptamers, DNAzymes, and aptazymes. We sum up the methods utilized in the amalgamation of complex nanostructures, survey the significant types of multifunctional nanoparticles that have been developed in the course of recent years, and give a perceptual vision of the significant field of nanomedicine. The field of DNA-functionalized nanoparticles holds an incredible guarantee in rising biomedical zones, for example, multimodal imaging, theranostics, and picture-guided treatments.

Introduction

Biomolecular functionalized nanoparticles (NPs) have started to be commercialized for their applications in diagnosis and therapeutics. A plethora of NPs have been investigated as tests for a scope of uses in detecting, imaging, and distinction of medication. Based on their shape and size, NPs can be categorized into 0D, 1D, 2D, or 3D. The size of the NPs influences the overall physicochemical properties of NPs; for example, 20 nm gold (Au), silver (Ag), platinum (Pt), and palladium (Pd) NPs have different optical properties, showing characteristic wine red, black, yellowish gray, and deeper black colors, respectively. NPs are themselves complex molecules made up of three layers: (a) The outermost layer is functionalized by surfactants, polymers, and metal ions which are smaller in size. (b) The shell covering is chemically different from the core material of NPs. (c) The core points to the NP itself. NPs are categorized based on their morphology, size, and chemical properties. Some of the common NPs based on their physical and chemical properties are (a) carbon-based NPs, (b) ceramic NPs, (c) semiconductor NPs, (d) polymeric NPs, and (e) lipid-based NPs.1 The characteristic electronic, optical, attractive, and mechanical properties of both natural and inorganic nanoparticles make them a perfect contender for use as an enclosing and delivery agent of biosensing, imaging tests, and therapeutic loads. Given their robust chemical composition and ease of surface functionalization, nanoparticles can be fine-tuned for controlled, stimulus-triggered release of cargo in the biological milieu. Owing to specific display of functionalized ligands on their surfaces, the interactions of nanoparticles with cellular systems have been optimized to make functionalized nanoparticles one of the main drivers of next-generation nanomedicine. Increasing the specificity of nanoparticles through surface ligands and minimizing off-target binding and possible side effects is currently a key focus in the research pertaining to precision and customized nanomedicine.

The therapeutic interest of nanoparticles has set off the advancement of functionalized, theranostics nanoparticles that combine diagnosis, drug tracking, target-specific delivery, and controlled medication discharge in a solitary stage. Nanoparticles with multimodal imaging potentials offer better images at different length scales or treatment stages, allowing more accurate disease diagnosis, thus facilitating better therapeutics. Although nanoparticles might resemble the smart nanorobots, they indeed have the potential to operate in an integrated way, offering invaluable assistance in disease diagnosis and treatment.

One of the primary functionalizations that allows the use of nanoparticles in biomedical applications is conjugation with DNA. Attachment of nanoparticles to diverse structural and functional DNA sequences can be made by forming (a) hybridization-based double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), (b) aptamers (bind selectively to targets), (c) DNAzymes (just like enzymes catalyze reactions), and (d) aptazymes (are a combination of the aptamers and DNAzymes). Hypothetically such DNA entities can be created against any biological target in a test tube through a procedure called systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX).2 Ease of synthesis, low immunogenicity, small size, ease of chemical modification, as well as controlled functionalization on nanoparticle surfaces, all favorable features for biological applications, can be provided by DNA-based motifs such as aptamers. Coating of nanoparticle surfaces with such DNA entities makes nanoparticles compatible to be targeted to most biological receptors which can range from simple biomolecules to entire viruses or even mammalian cells.

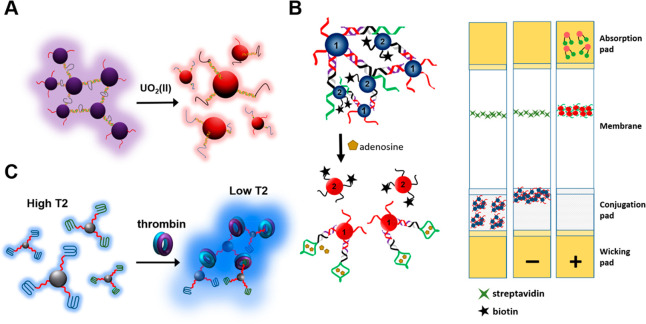

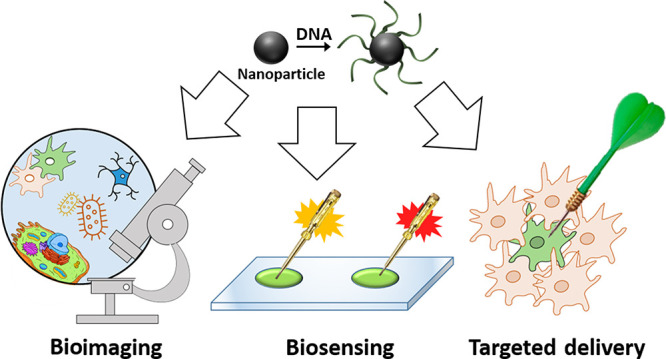

Multiple strategies have been explored recently to construct DNA-functionalized nanoparticles for their potential applications in nanomedicine. Strategies to functionalize nanoparticles with DNA and other fundamental properties of nanoparticles that make them useful in biological applications have been extensively covered before.3 Apart from biological applications, DNA-conjugated nanoparticles are also used in materials science for the creation of unique architectures and crystal engineering that are not feasible through top-down construction approaches.4 In this mini-review, we discuss key developments in DNA-functionalized nanoparticles functionalized with aptamers, DNAzymes, and aptazymes. We provide recent examples of DNA-functionalized nanoparticles from the aspects of target-specific biosensing, bioimaging, and drug delivery. Finally, we present our vision and perspectives for the translation of DNA-functionalized nanoparticles into real-world devices with a multitude of biomedical applications (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of DNA-functionalized nanoparticles. DNA-functionalized nanoparticles have been immensely explored for their potential applications in different areas of biomedical research. In the scope of this mini-review, we broadly divide them into three categories: (a) biosensing, (b) bioimaging, and (c) targeted drug delivery in living systems.

DNA Motifs Used for Functionalizing Nanoparticles

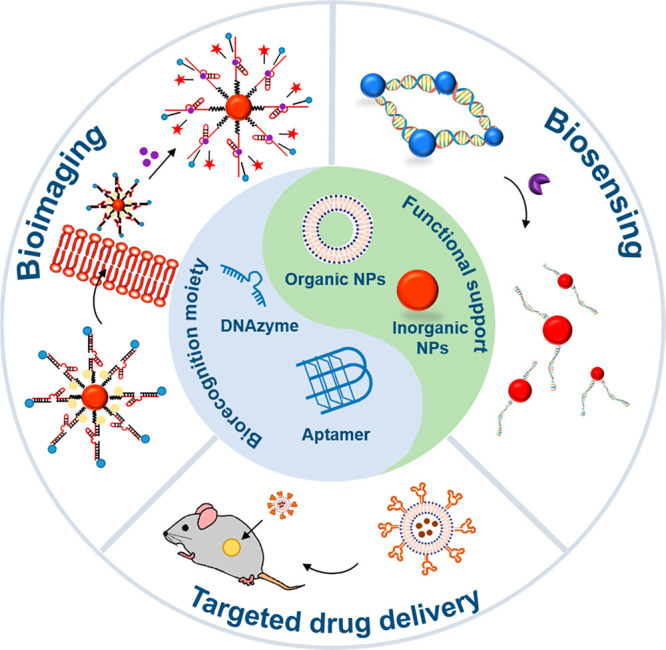

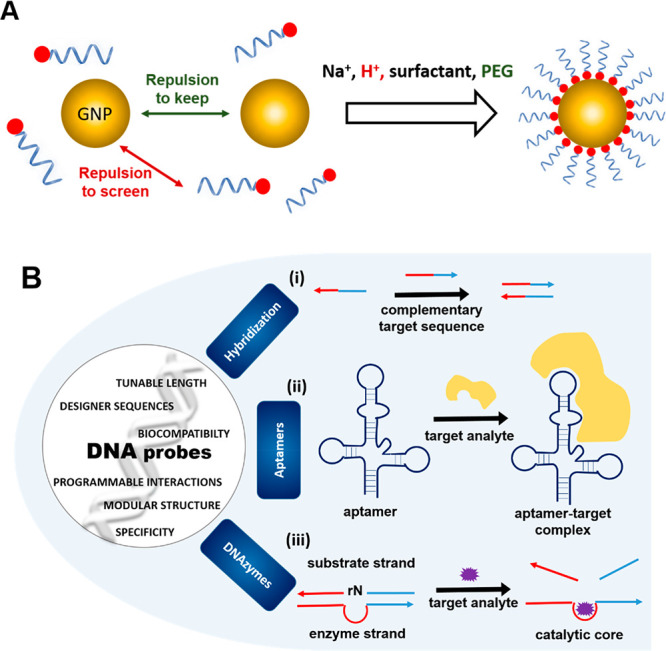

A variety of biomolecules have been functionalized on nanoparticles for different purposes. Of these, DNA-based nanoparticles have emerged as probes of choice due to the programmable nature of DNA and robust chemical modifications available on DNA, thus aiding coupling it to multiple types of organic and inorganic nanoparticles, a property that has driven the emergence of an entirely separate field of research—DNA nanotechnology (Figure 2A).5 DNA oligonucleotides, also called staples, can be synthesized up to hundreds of bases in sequence, at relatively low cost, in high purity and high yield. Further, compared to other biomolecules, DNA is more robust and amenable for chemical modifications in the nucleotide sequence, sugar modification, or phosphate backbone modifications, thus providing a huge diversity in terms of chemical functionality. Importantly, DNA-based probes are extremely biocompatible and nontoxic to cells. They can be conjugated to multiple types of nanoparticles, and these DNA-functionalized nanoparticles are taken into cells and have also been shown to play a role in gene regulation of targeted cells.

Figure 2.

(A) DNA-functionalized nanoparticles and (B) different DNA motifs used for functionalizing nanoparticles. There are broadly three classes of nucleic acid probes: (i) hybridization-based probes, (ii) aptamers, and (iii) DNAzymes. Single-stranded hybridization-based probes identify a complementary target strand through Watson–Crick base pairing. Aptamers are oligonucleotides advanced through combinatorial choice procedures that can tie to analytes of enthusiasm including particles, atoms, and proteins. Aptamers frequently embrace complex tertiary structures that empower target acknowledgment. Then again, target binding can incite conformational changes in their structure. DNAzymes are comprised of a substrate strand and a catalyst strand (containing a synergist center) hybridized to one another. Reproduced with permission from ref (9). Copyright 2019 John Wiley and Sons.

A variety of methods have been used to functionalize the DNA onto the surface of nanoparticles, such as covalent conjugation, dative bonding, electrostatic interaction, etc. In the case of the covalent mode of functionalization, reagents of EDC/NHS chemistry are being used, but it may reduce the quantum yield of nanoparticles. In dative bonding there can be aggregation of nanoparticles as these bonds between monothiols and nanoparticles can be easily broken because of high temperature and oxidation. Electrostatic interaction is formed by opposite charges but is nonspecific in nature. Another method to synthesize DNA-functionalized nanoparticles apart from traditional method is biotemplated synthesis of nanoparticles.6 These DNA-functionalized nanoparticles have stronger dative bonding and are much more stable thermally. Nanoparticles are predominantly coated with single-stranded DNA sequences that through very specific Watson Crick base pairing can easily bind to complementary nucleic acid sequences. Hybridization-based probes including mRNA, microRNA, and noncoding RNA are used in the detection of nucleic acids (Figure 2B-i).7

Single-stranded DNA sequences can also be evolved by selection techniques such that they recognize and bind to any target molecule of interest (aptamers) or catalyze specific chemical or biochemical reactions (DNAzymes).8 Aptamers can be generated against any target through an in vitro process called SELEX.2 Aptamers represent DNA analogues of antibodies; it is well established in some cases that their performance metrics (target-binding affinities and detection limits) are much higher than classical antibodies, and DNA provides this advantage at a reduced cost and greater stability as compared to antibodies.9 Aptamers can be evolved in the laboratory using the simple secondary structure of DNA alone, without having definite information on tertiary folding. More than 500 aptamers have been created for in excess of 100 unique targets, going from ions, atoms, proteins, to entire cells (Figure 2B-ii).9

DNAzymes, just like aptamers, have similar DNA structures that catalyze specific chemical or biochemical reactions.8 DNAzymes can also be obtained in vitro using a process similar to that of aptamers. DNAzymes have been used to detect multiple metal ions, although recent work has shown the catalytic activity of DNAzymes in detecting other analytes such as RNA (Figure 2B-iii).10 Hybrid probes which leverage the properties of two or more of the above such classes of molecules have also been realized. Aptazymes is a term for DNA entities which integrates the functionalities of aptamers and aptazymes in the same species.11 In aptazymes, the catalytic activity of DNA is activated only post binding to target through its aptamer domain (Figure 2B-iii).

DNA-Functionalized Nanoparticles for Biosensing Applications

There are no functional groups present on DNA sequences alone that can generate noticeable signals in solutions directly. The DNA sequences are converted into sensing probes by coupling them to inorganic NPs through thiol–Au coupling. These DNA–NP conjugates can be used for biosensing based on different properties of nanoparticles such as their unique optical and magnetic properties.10

DNA–NP-based colorimetric sensors have been developed using labeled as well as label-free methods. The labeled method first conjugates DNA to GNPs and is subsequently exposed and binds analytes of choice. There is a color change in the solution as the target binding triggers either assembly or disassembly of GNPs. This is due to a plasmon resonance peak shift of GNPs (Figure 3A).12 Multiple such colorimetric sensors based on DNA–GNP aggregation have been used to sense metal ions12 and biomolecules. The labeled method of biosensing requires the covalent conjugation of DNA to GNPs. Different noncovalent adsorption behaviors of single-stranded and double-stranded DNA molecules on GNPs are being used for a label-free method, with analyte-stimulated aggregation of GNPs in high salt concentrations. Similar to labeled detection, a label-free method of detection has also been used for extremely low nanomolar detection of UO22+ and Pb2+ using DNAzyme–GNP complexes.12

Figure 3.

(A) Colorimetric sensors dependent on the dismantling of GNPs connected by a uranyl-specific DNAzyme. Reproduced with permission from ref (12). Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society. (B) Aptamer/GNP-based horizontal stream gadget: adenosine-initiated dismantling of aptamer-connected GNPs and schematic representation of sidelong stream gadgets stacked with assembled GNPs before use (left strip) and in a negative (center strip) or a positive (right strip) test. Reproduced with permission from ref (13). Copyright 2006 John Wiley and Sons. (C) Structure of MRI contrast agent dependent on thrombin-prompted assembly of aptamer-functionalized SPIOs, changing from high to low spin–spin relaxation time (T2). Reproduced with permission from ref (14). Copyright 2007 John Wiley and Sons.

The lateral flow assays in dip stick format have been adapted to use the concept of target-induced assembly and disassembly of DNA–GNPs (Figure 3B).13 Here, lateral flow devices (LFDs) are loaded with non-cross-linked DNAzyme–GNP conjugates or aptamer-linked GNP aggregates (Figure 3B),13 allowing solution-based assays on LFDs for one-step colorimetric detection of multiple targets. These devices remarkably simplify the test operations, enabling the use of DNA–GNPs for point-of-care (POC) and home-based diagnostics.

Quantum dots (QDs), inorganic nanoparticles with extremely bright fluorescence, have been incorporated into GNP aggregates for photoluminescent detection of different targets in one assay. Other classes of nanoparticles such as superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs (SPIOs) hold peculiar magnetic properties. The definite change of spin–spin relation time (T2) of SPIOs for the close by water protons could be produced by the assembly and disassembly of SPIOs. Smart magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents using DNA–SPIO conjugates were developed, based on this principle. For example, a “turn-off” thrombin-detecting MRI sensor was constructed based on the thrombin-induced assembly of SPIOs. Aggregation of nanoparticles by attaching to thrombin leads to a reduction in brightness of the MR image (Figure 3C).14 Similarly, a “turn-on” MRI sensor for adenosine detection was constructed based on adenosine-induced disassembly of prearranged SPIO aggregates connected to aptamer strands forming cross-links. The disassembly of SPIO aggregates on addition of adenosine leads to brighter MR image and larger T2. Aptamer-modified SPIOs used for sensitive detection of cancer cells have been reported by the Tan group.14 While most current MRI techniques can recognize tissue harm and tumor development, which is regularly past the point of no return for preventative medication, the strategies introduced by such DNA–SPIOs may permit recognition of protein and metabolite biomarkers directly at the beginning of tumor improvement.

DNA-Engineered Nanoparticle Systems for Targeted Bioimaging in Living Cells

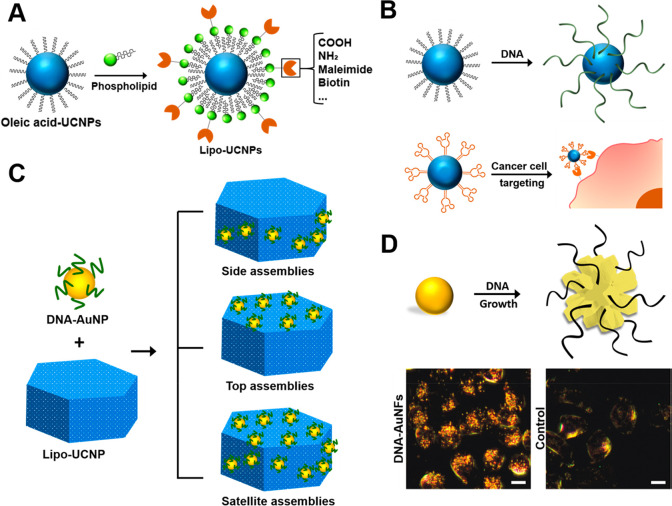

Nanoparticles doped with rare-earth ions display a very peculiar feature which is why they are called UpConversion NanoParticles (UCNPs). The exceptional property shown by these nanoparticles, to upconvert near-infrared (NIR) radiation into shorter-wavelength photoluminescence, makes them highly useful in diagnostic and bioimaging applications. Numerous methodologies have been tried to join DNA onto UCNP surfaces for bioimaging; however, these conventions request three basic steps: change of UCNPs into water-dissolvable structures, surface alteration of functional groups, trailed by conjugation of DNA. These basic multistep synthesis frequently lead to low conjugation reproducibility and effectiveness. To address this difficulty, Li and colleagues created ways to synthesize DNA-functionalized UCNPs in a smaller number of steps for biological imaging and sensing. They covered a UCNP with functionalizable phospholipids that filled in as the conjugation trap for various biomolecules (Figure 4A).15 The lipids of the outer cell membrane are mimicked by these phospholipids, comprised of a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) segment, two fatty chains, and a functional group. The phospholipids exhibit amphiphilic behavior which drives the hydrophobic association of the tail of the lipids to the nanoparticle surface. Once coated on UCNPs, the hydrophilic part of the phospholipid is pointed outward toward the aqueous environment, facilitating the PEG modification on the UCNP’s surface and thus making the UCNPs, which are earlier hydrophobic, now water-soluble. Apart from that, functional groups like carboxylic acid, amine, and maleimide allow the UCNPs to be modified with diverse biomolecules. Thiol-modified DNA was coupled in high yields with maleimide-modified lipids on UCNPs to achieve DNA coupling on UCNPs. Importantly, DNA molecules implanted onto lipid-coated UCNPs keep their specific biorecognition properties.

Figure 4.

(A) Functionalizable and water-dispersible UCNPs synthesized by biomimetic surface engineering using phospholipids. Reproduced with permission from ref (15). Copyright 2013 John Wiley and Sons. (B) Schematic of DNA-functionalized UCNPs synthesized through a simple one-step ligand exchange strategy and aptamer-coated UCNPs for targeting cancer cells. Reproduced with permission from ref (16). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. (C) Heteroassembly superstructures of DNA-Au/UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref (17). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (D) Diagram of DNA–AuNF sequence-specific synthesis and dark-field image of CHO cells treated with DNA–AuNFs or without treatment. Reproduced from ref (18). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

The same group went on to explore one step process of DNA-UCNP hybrids synthesis using hydrophobic UCNPs (Figure 4B).16 A new strategy was developed to use DNA molecules instead of original oleate ligands on UCNPs through simple one-step ligand-exchange procedure. The recognition capacities of DNA molecules present on the surface of UCNPs leads to formation of programmable NP assembly with multiple DNA strands. Though negatively charged due to presence of DNA coating, uptake of DNA – UCNPs by cells did not required transfection agents. The DNA–UCNPs were able to be uptaken by cells without the need for transfection agents and their application for DNA delivery and continuous imaging was also exhibited. The method allowed the authors to modify specific recognition abilities of the UCNPs coated with DNA aptamers for targeted imaging of cancer cells. For example, UCNPs attached with a DNA aptamer that can target nucleolin (AS1411), was used for targeting MCF-7 cancer cell line (Figure 4B).16 AS1411-coated UCNPs incubated with MCF-7 cells, cells showed a strong upconversion luminescent image compared to control nanoparticles. These surface engineered UCNPs showed that they can be easily uptaken in cancer cells via aptamer-dependent nucleolin-receptor-mediated endocytosis.

GNPs are not fluorescent in visible spectrum but they can be combined with complementary fluorescent materials to achieve multimodal bioimaging.17 Li and colleagues designed an innovative approach for targeted dual-modality bioimaging using regiospecific assembly of DNA–GNP conjugates onto UCNPs (Figure 4C).17 Using DNA–GNPs, specifically assembled on the hexagonal plate-like surface of UCNPs with rigid stoichiometry, leading to multiple addressable superstructures. The plasmonic resonance of GNPs combined with the fluorescent properties of UCNPs opens up numerous avenues for dual-modality imaging probes. This approach enables us to do targeted bioimaging in living system by allowing polyvalent DNA displayed on the superstructure surface. The specific molecular recognition abilities of DNA–GNP–UCNP superstructures make them very useful for targeted bioimaging. For targeted imaging of cancer cells, the same group developed aptamer-functionalized hybrid assemblies. Strong upconversion luminescence along with light-scattering signal were displayed by the cells incubated with AS1411-functionalized GNP–UCNPs as compared to control nanoparticles, indicating successful targeting and uptake of a dual-nanoparticle probe mediated by aptamer-based recognition of membrane receptors.

GNPs present very unique absorption and emission properties which make them ideal for multiple imaging modalities such as photothermal imaging, two-photon luminescence imaging, and photoacoustic imaging. These properties of GNPs depend on critical structural properties such as different surface features and shapes since the resulting geometries control optical properties of GNPs. For programmable manipulation of the surface geometries and properties of GNPs, distinctive molecular encapsulators such as surfactants have been developed that control nanocrystal growth in a face-selective manner. However, to use GNPs in the imaging applications demands methodical conjugation chemistry methods for further surface engineering of these nanoparticles. Fine tuning of morphology of GNPs using DNA, thus tuning the optical properties of GNPs, was also explored (Figure 4D).18 The morphology of GNPs can be easily tuned using DNA in a sequence-dependent manner. As a demonstration, GNPs synthesized in the presence of 30-mer oligo-A or -C leads to the formation of flower-shaped NPs, while those synthesized in the presence of 30-mer oligo-T lead to normal gold nanospheres. Using thiolated DNA is one of the most frequent ways to couple DNA to GNPs. The only problem with thiolated DNA is that they can easily detach from GNPs in biofluids, in the presence of reducing agents. This limits the large-scale use of DNA–GNPs for therapeutic applications and imaging in living systems. However, the synthesis of GNPs in a DNA-controlled system with different morphologies led to a system where DNA was mostly retained on GNP surfaces even after overnight incubation with mercaptothiol, maybe because of integration of DNA into the GNPs during nanoparticle synthesis. Importantly, DNA exposed on the DNA–GNP surfaces keeps its biorecognition capability for complementary hybridization.

This enhanced biorecognition ability and DNA stability project DNA-conjugated nanoparticles as ideal tools for bioimaging applications. DNA-coupled nanoparticles of different shapes (such as the nanoflowers described above) could be easily uptaken by cells and visualized by light-scattering imaging, and DNA–gold nanoflowers (DNA–AuNFs) exhibit much higher brightness than DNA–GNP nanospheres of similar composition.18 This strategy of DNA-mediated growth of gold nanoparticles could easily be generalized for synthesis of multiple metallic NPs with numerous morphologies, including gold, silver, and lead–gold core–shell nanoparticles. Quantum dots (QDs) come with unique optical and electronic properties depending on their size, shape, and composition. These parameters control the band gap that can, in turn, tune the fluorescence emission continuously from 400 to 900 nm while showing high absorption cross section, high quantum yields at room temperature, and resistance to photobleaching. The low nonspecific binding between the QDs and the DNA bioconjugates helps in assembling these DNA-functionalized nanoparticles through base pairing. Different methods are being used in recent years to conjugate DNA on the surface of QDs, namely, covalent interaction, direct dative interaction, electrostatic interaction, etc.19 Biotemplated synthesis of QDs can be used to directly attach DNA on a nascent nanoparticle’s surface, as compared to other traditional methods. The investigation of this synthesis procedure gives further bits of knowledge on the molecular mechanisms of morphological control of any nanoparticle by topping ligands that are attached to various facets and further opening numerous roads for different biomedical applications.

DNA-Engineered Nanoparticle Systems for Targeted Drug Delivery Applications in Living Systems

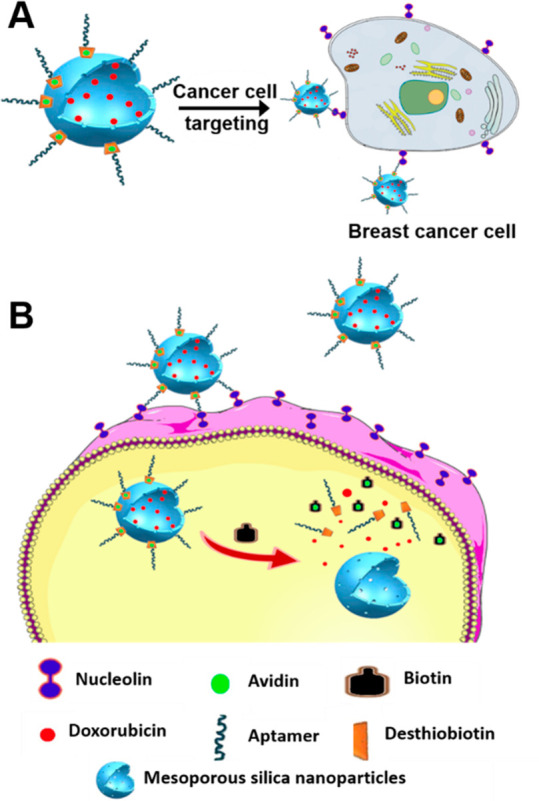

In vivo drug delivery using multivalent nanoparticles provides control over the targeted and controlled release of therapeutics in tumor tissues. It can thus overcome the unwanted side effects of classical chemotherapy-based treatments. In order to achieve this, mesoporous silica-based nanoparticles (MSNs) have been explored extensively for drug delivery applications owing to their biocompatible nature and easy alteration of nanopores for trapping and release of multiple therapeutics. Aptamer specific to cancer cells can be coupled to such silica nanocarriers to develop smart drug delivery systems to target cancer cells (Figure 5A).20 The previously described AS1411 aptamer was similarly coupled to the MSN surface for recognizing nucleolin-overexpressing breast cancer cells specifically. The mesoporous structure allowed high drug loading as compared to solid nanoparticles. Aptamer-driven cellular targeting of the drug-loaded silica nanoparticles showed much efficient killing of cancer cells compared to unfunctionalized NPs.

Figure 5.

(A) Aptamer-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. (B) Vitamin H or biotin-responsive drug release based on an aptamer–MSN-targeted delivery system.

Intracellular stimuli-responsive drug release is yet another parameter that needs to be optimized to improve the onsite drug delivery. Active cellular targeting in combination with stimuli-responsive drug release could increase drug efficiency and decrease off-target effects in living systems. A better version of MSN-based smart drug delivery systems for cancer targeting in parallel to responsive intracellular drug release was recently demonstrated (Figure 5B).21 The pores of MSNs were loaded with cancer chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin (DOX), capped with avidins. The surface of MSNs was functionalized with a DNA aptamer, sgc8, to target the tyrosine kinase 7, which is a cell membrane receptor protein. During the process of delivery, there is no drug release owing to the capped nanoparticles. When uptaken by the cells, the cytoplasmic vitamin H (commonly known as Biotin, present in higher concentration in cancer cells) stimulates cap opening and releases the encapsulated drug inside the targeted cells. Such multimodal nanoparticle-based systems could minimize the undesirable off-target effects and demonstrate remarkable increment in destruction of cancer cells over free drugs or drug-loaded nanoparticles without an active targeting module. Vries et al. used a similar targeting strategy to increase the retention time of antibacterial drugs on the corneal surface of the eyes. Aptamer-modified DNA–lipid nanoparticles have been used in an aqueous medium and used as an eye drop for ophthalmic drug delivery.22,23 Thus, designer nanoparticles serve two purposes—as vessels for carrying the drugs and, at the same time, as a platform for coupling DNA aptamers for active targeting to cancer cells.

Challenges and Future Prospects

We have briefly summarized the recent trends in engineering functional DNA-based multiple nanoparticle systems for various biomedical applications. The current emphasis on research involving nanoparticles includes several strategies for incorporating the biorecognition abilities of DNA with distinctive optical, magnetic, and electronic properties of nanoparticles for sensitive and fast detection of analytes, targeted delivery, and bioimaging. Due to the limited scope of this mini-review, we have covered only key discoveries involving inorganic nanoparticles for these applications. There is an equivalent wave of research involving similar research with organic nanoparticles like graphene or carbon-based materials. In any case, in spite of the kind of nanoparticles utilized for these applications, the improvement of novel nanoscale reporters and transducers, DNA design, and the controlled coupling of DNA on just explicit nanoparticle surfaces are pivotal and developing to accomplish the superior requests of cutting-edge nanomedicine-based therapeutics.

With the rapid development of nanoparticles with controlled and on-demand provision of optical, magnetic, and electronic properties, a multitude of DNA nanoparticle systems have been explored and designed for point-of-care diagnostics. Notwithstanding, there are still difficulties that require further enhancement and improvement before these nanoparticle systems become ready to hit real markets. DNA-based diagnostic revolution still awaits fully operational improvement of profoundly alluring homogeneous “bind and detect” assays which are fast, sensitive, and cost-effective compared to classical antibody-based assays. Some arenas where DNA clearly offers advantages over antibodies are small-molecule targets that antibodies fail to bind/recognize. DNA-based sensors can be used as commercial products because of their ability to detect small molecules. There is clearly an increasing demand for the development of DNA-based sensors for more clinically relevant targets to attract the attention of the medical and biomedical community. In parallel, DNA-based sensors developed so far could be combined with existing devices. For example, lately, a DNA-based sensor was joined with a routinely utilized personal glucose meter (PGM) to distinguish numerous objectives. Along these lines quickening the speed of interpretation by consolidating research with item improvement and scaling-up assembly steps that the current point of care gadgets has set up.

Aptamer-mediated nanoparticle delivery in biological systems has shown promise in improving the delivery success and reducing the side effects caused by off-target piling up of therapeutic drugs or diagnostic agents. However, in the current scenario, research in the field of targeted drug delivery falls far behind from reaching clinical trials. Multiple crucial problems such as lack of aptamers for clinically relevant targets, lack of large-scale manufacturing infrastructure for these materials, biocompatibility, and toxicity have hindered the real commercialization of these nanosystems. Optimization is greatly needed in the aspects where cancer-targeted aptamers are used to improve the pharmacokinetic profiles and targeting specificities of established nanocarriers like liposomes. Such endeavors could provide a promising route to lower the development costs and facilitate new development cycles. Other avenues to improve targeted nanoparticle therapy might explore external stimuli such as ultrasound or the photothermal effect to control drug release24 or the use of checkpoint inhibitors (such as CTLA-4 or PD-L1 inhibitors) as accompanying immunotherapy agents to improve the efficacy of nanoparticle-based treatments.25 Most importantly, toxicity assessment of DNA-based nanoparticles demands more consideration for their likely clinical interpretation. An integrated, targeted, focused, interdisciplinary collaborative research by nanotechnologists, biologists, biomedical experts, and clinicians is needed to project DNA–NPs in advancing both clinical applications and the fundamental science of next-generation nanomedicine.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Profs. Sharad Gupta and Himanshu Shekar, at IIT Gandhinagar, India and all the members of DB group for critically reading the manuscript and their valuable feedback. US, VM, AR thank IITGN-MHRD, GoI for fellowship. DB thanks SERB, GoI for Ramanujan Fellowship and IIT Gandhinagar and BARC-BRNS for research grant. The work in host laboratories are funded by MHRD and DST-SERB and GSBTM, GoI.

Biographies

Dhiraj Bhatia is an Assistant Professor and Ramanujan Fellow in Biological Engineering at Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar (IITGN). He obtained his PhD from National Center for Biological Sciences, TIFR and worked as HFSP Postdoctoral fellow at Institut Curie, Paris before establishing his laboratory at IITGN, India in 2018.

Bhaskar Datta is an Associate Professor in Chemistry with joint appointment with Biological Engineering at Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar (IITGN). He obtained his PhD from Carnige Mellon University and worked as Postdoctoral fellow at Georgia Institute of Technology followed by Assistant Professor at Missouri State University, USA before moving and establishing his laboratory at IITGN in 2011.

Chinmay Ghoroi is an Professor in Chemical Engineering at Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar (IITGN). He obtained his PhD from Indian Institute of Tecchnology Bombay and worked as Postdoctoral fellow at New Jersey Institute of Technology, USA before moving and establishing his laboratory at IITGN in 2009.

Arun Richard Chandrasekaran is Scientist at the RNA institute, University of Albany, USA. He obtained his PhD from New York University, USA under the guidance of Prof. Nadrian Seeman and moved to work as Postdoctoral fellow at the RNA Institute at Albany, USA.

Udisha Singh and Anjali Rajwar are PhD students under the supervision of Dr. Dhiraj Bhatia in Biological Engineering at IIT Gandhinagar while Vinod Morya is a PhD student under the supervision of Prof. Chinmay Ghoroi at IIT Gandhinagar.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Khan I.; Saeed K.; Khan I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arabian J. Chem. 2019, 12 (7), 908–931. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Cao Z.; Lu Y. Functional nucleic acid sensors. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109 (5), 1948–1998. 10.1021/cr030183i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Wang F.; Sheng J.-L.; Sun M.-X. Advances and Application of DNA-functionalized Nanoparticles. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 26 (40), 7147–7165. 10.2174/0929867325666180501103620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N.; Minevich B.; Liu J.; Ji M.; Tian Y.; Gang O. Directional Assembly of Nanoparticles by DNA Shapes: Towards Designed Architectures and Functionality. Top Curr. Chem. (Z) 2020, 378, 36. 10.1007/s41061-020-0301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkin C. A.; Letsinger R. L.; Mucic R. C.; Storhoff J. J. A DNA-based method for rationally assembling nanoparticles into macroscopic materials. Nature 1996, 382 (6592), 607–609. 10.1038/382607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algar W. R.; Prasuhn D. E.; Stewart M. H.; Jennings T. L.; Blanco-Canosa J. B.; Dawson P. E.; Medintz I. L. The controlled display of biomolecules on nanoparticles: a challenge suited to bioorthogonal chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22 (5), 825–858. 10.1021/bc200065z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. K.; Jung W. Y.; Park M. G.; Song S. K.; Lee Y. S.; Heo H.; Kim S. Bioimaging of multiple piRNAs in a single breast cancer cell using molecular beacons. MedChemComm 2017, 8 (12), 2228–2232. 10.1039/C7MD00515F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein M. DNA catalysis: the chemical repertoire of DNAzymes. Molecules 2015, 20 (11), 20777–20804. 10.3390/molecules201119730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta D.; Ebrahimi S. B.; Mirkin C. A. Nucleic-acid structures as intracellular probes for live cells. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32 (13), 1901743. 10.1002/adma.201901743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H.; Li X.-F.; Zhang H.; Le X. C. A microRNA-initiated DNAzyme motor operating in living cells. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famulok M.; Hartig J. S.; Mayer G. Functional aptamers and aptazymes in biotechnology, diagnostics, and therapy. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107 (9), 3715–3743. 10.1021/cr0306743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H.; Wang Z.; Liu J.; Lu Y. Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric sensors for uranyl (UO22+): Development and comparison of labeled and label-free DNAzyme-gold nanoparticle systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (43), 14217–14226. 10.1021/ja803607z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Mazumdar D.; Lu Y. A simple and sensitive “dipstick” test in serum based on lateral flow separation of aptamer-linked nanostructures. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45 (47), 7955–7959. 10.1002/anie.200603106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yigit M. V.; Mazumdar D.; Kim H. K.; Lee J. H.; Odintsov B.; Lu Y. Smart “turn-on” magnetic resonance contrast agents based on aptamer-functionalized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. ChemBioChem 2007, 8 (14), 1675–1678. 10.1002/cbic.200700323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. L.; Zhang R.; Yin L.; Zheng K.; Qin W.; Selvin P. R.; Lu Y. Corrigendum: biomimetic surface engineering of lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles as versatile bioprobes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (32), 8190–8190. 10.1002/anie.201305509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. L.; Wu P.; Hwang K.; Lu Y. An exceptionally simple strategy for DNA-functionalized up-conversion nanoparticles as biocompatible agents for nanoassembly, DNA delivery, and imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (7), 2411–2414. 10.1021/ja310432u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.-L.; Lu Y. Regiospecific hetero-assembly of DNA-functionalized plasmonic upconversion superstructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (16), 5272–5275. 10.1021/jacs.5b01092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Zhang J.; Ekman J. M.; Kenis P. J.; Lu Y. DNA-mediated control of metal nanoparticle shape: one-pot synthesis and cellular uptake of highly stable and functional gold nanoflowers. Nano Lett. 2010, 10 (5), 1886–1891. 10.1021/nl100675p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A.; Pons T.; Lequeux N.; Dubertret B. Quantum dots–DNA bioconjugates: synthesis to applications. Interface Focus 2016, 6 (6), 20160064. 10.1098/rsfs.2016.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. L.; Yin Q.; Cheng J.; Lu Y. Polyvalent mesoporous silica nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates target breast cancer cells. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2012, 1 (5), 567–572. 10.1002/adhm.201200116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.-L.; Xie M.; Wang J.; Li X.; Wang C.; Yuan Q.; Pang D.-W.; Lu Y.; Tan W. A vitamin-responsive mesoporous nanocarrier with DNA aptamer-mediated cell targeting. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49 (52), 5823–5825. 10.1039/c3cc41072b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries J. W.; Schnichels S.; Hurst J.; Strudel L.; Gruszka A.; Kwak M.; Bartz-Schmidt K.-U.; Spitzer M. S.; Herrmann A. DNA nanoparticles for ophthalmic drug delivery. Biomaterials 2018, 157, 98–106. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshaer W.; Hillaireau H.; Fattal E. Aptamer-guided nanomedicines for anticancer drug delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2018, 134, 122–137. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rwei A. Y.; Paris J. L.; Wang B.; Wang W.; Axon C. D.; Vallet-Regí M.; Langer R.; Kohane D. S. Ultrasound-triggered local anaesthesia. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1 (8), 644–653. 10.1038/s41551-017-0117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios-Doria J.; Durham N.; Wetzel L.; Rothstein R.; Chesebrough J.; Holoweckyj N.; Zhao W.; Leow C. C.; Hollingsworth R. Doxil synergizes with cancer immunotherapies to enhance antitumor responses in syngeneic mouse models. Neoplasia 2015, 17 (8), 661–670. 10.1016/j.neo.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]