Abstract

Background

Advanced heart failure (AHF) carries a morbidity and mortality that are similar or worse than many advanced cancers. Despite this, there are no accepted quality metrics for end‐of‐life (EOL) care for patients with AHF.

Methods and Results

As a first step toward identifying quality measures, we performed a qualitative study with 23 physicians who care for patients with AHF. Individual, in‐depth, semistructured interviews explored physicians' perceptions of characteristics of high‐quality EOL care and the barriers encountered. Interviews were analyzed using software‐assisted line‐by‐line coding in order to identify emergent themes. Although some elements and barriers of high‐quality EOL care for AHF were similar to those described for other diseases, we identified several unique features. We found a competing desire to avoid overly aggressive care at EOL alongside a need to ensure that life‐prolonging interventions were exhausted. We also identified several barriers related to identifying EOL including greater prognostic uncertainty, inadequate recognition of AHF as a terminal disease and dependence of symptom control on disease‐modifying therapies.

Conclusions

Our findings support quality metrics that prioritize receipt of goal‐concordant care over utilization measures as well as a need for more inclusive payment models that appropriately reflect the dual nature of many AHF therapies.

Keywords: end‐of‐life care, heart failure, hospice

Subject Categories: Heart Failure, Quality and Outcomes

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AHF

advanced heart failure

- CARD

cardiologist

- EOL

end‐of‐life

- HF

heart failure cardiologist

- PCP

primary care physician

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Our study found that physicians caring for patients with advanced heart failure have varying views of what constitutes high‐quality end‐of‐life care.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our findings indicate a need for quality metrics prioritizing receipt of value‐concordant care.

Patients with advanced heart failure would also benefit from inclusive payment models that allow receipt of disease‐modifying therapies concurrently with hospice.

Advanced heart failure (AHF) carries a mortality rate similar to, or worse than, many cancers. 1 Patients with AHF report high symptom burden 2 , 3 and more physical complaints and depression than patients with metastatic cancer. 4 Unfortunately, there are no widely accepted quality measures to guide improvement in end‐of‐life (EOL) care for patients with AHF.

Quality metrics for EOL care have been successfully implemented for advanced cancer. Earle and others conducted qualitative studies of patients, family members, oncologists, and relevant stakeholders 5 and analyzed national administrative claims data, to determine benchmarks. 6 Established standards for high‐quality EOL care included rates of hospice admission (≥55%), hospitalizations and emergency room visits in the last month of life (≤4%), admission to the intensive care unit (≤4%), and death in the hospital (<17%). These benchmarks were subsequently endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Quality Forum 7 and have been applied widely in analyses of quality of EOL care for patients with cancer. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 However, no similar efforts have been undertaken to develop EOL care quality indicators for patients with AHF.

There are several important differences between heart failure and cancer, which make generalizing EOL care quality indicators from cancer to patients with AHF challenging. 14 First, evidence suggests that patients with AHF may be more accepting of hospitalizations and hospital deaths than patients with cancer. 15 , 16 The disease trajectories for patients with AHF and cancer also differ markedly, with greater perceived prognostic uncertainty for heart failure. 17 , 18 , 19 Many patients with AHF die suddenly; those who do not typically have a disease course marked by recurrent exacerbations, often for years. 14 , 20 Complicating matters, evidence suggests that patients with heart failure, unlike patients with cancer, often have poor prognostic understanding 21 , 22 , 23 and do not view their disease as terminal. 22 , 24 , 25 Lastly, contemporary heart failure care focuses on invasive life‐prolonging therapies, such as left ventricular assist device (LVAD) insertion, 26 occasionally to the exclusion of palliative care. 22 , 27

This study aimed to begin addressing these challenges by identifying acceptable quality measures for EOL care for patients with AHF. We explored how physicians (cardiologists and primary care physicians [PCPs]) define high‐quality EOL care for patients with AHF, and what barriers they encounter in delivering such care. In order to maximize the representativeness of our findings, we purposively included physicians providing care in rural communities to capture how rurality affects the quality of EOL care. Prior research has demonstrated differences in EOL care based on rurality, which has been attributed in part to access to in‐home care such as hospice services 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ; rurality also likely affects EOL care by limiting access to specialists and advanced therapies. By accounting for this factor, we sought to generate an inventory of potential indicators of high‐quality EOL care that would be applicable across different geographical care settings.

Methods

Study Design, Participants, and Data Collection

We conducted in‐depth, semistructured qualitative interviews between January 1, and December 31, 2018 with physicians who care for patients with AHF in the state of Maine. Purposive sampling was conducted to recruit physicians representing multiple specialties and practice settings (including rural, semirural and urban). Physicians were identified through snowball recruiting by practice leaders in cardiology and through web searches to ensure sampling of physicians practicing in rural environments. Rurality was determined based on rural‐urban commuting area codes using the zip code of the physician's clinical office. There were 4 heart failure specialists in the state of Maine at the time of this study; 1 was an investigator and did not participate, the remaining 3 were participants. Interviews lasted about an hour, and were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized by a professional transcription service. Deidentified transcripts are available from the corresponding author upon request. Verbal consent was obtained; the project was approved by the Maine Medical Center institutional review board.

Interview Content

Interviews were conducted by trained qualitative researchers (C.G., H.M.) who followed a moderator guide designed by an interdisciplinary team composed of a qualitative physician researcher (P.H.), palliative medicine physicians (P.H., R.H.), and an experienced heart failure cardiologist (D.S.). We used a semistructured interview guide consisting of open‐ended questions and closed‐ended probes designed to explore providers' opinions regarding how they define high‐quality EOL care for patients with AHF, barriers to providing high‐quality EOL care, and the ways rurality affects EOL care. After conducting and analyzing 3 interviews, the interview guide was modified to improve flow and clarity (see Table S1 for final interview guide).

Data Analysis

The current analysis focused on defining characteristics of, and barriers to, high‐quality EOL care for patients with AHF. MaxQDA 32 was used for in‐depth analysis and line‐by‐line software‐assisted coding using an inductive, constant comparative method of analysis aimed at approaching the data with minimal preconceptions and identifying key themes and relationships between them. First, 3 investigators (R.H., C.G., H.M.) developed a preliminary codebook by independently reading 3 transcripts, categorizing participants' verbatim statements (open coding), and organizing emergent themes (axial coding). 33 The preliminary codebook was reviewed by the entire coding team (R.H., C.G., H.M., P.H.) and areas of disagreement were resolved with discussion. This work culminated in a single working codebook that 3 investigators (R.H., C.G., H.M.) used to code the remaining transcripts. Weekly meetings were held to discuss coding decisions, identify new themes and resolve coding disagreement for each transcript. Analysis occurred concurrently with interviews. The interview guide was modified after the first 3 coding sessions based on initial findings. The interview guide was not revised further; however, as the study progressed, the focus of the interviews was changed based on the coding discussions, to prioritize questions that were generating new themes, and deprioritize questions that were not. Finally, 3 investigators (P.H., R.H. and C.G.) conducted a secondary review of all coded text to organize dominant themes. Themes were further refined with a heart failure specialist (D.S.).

Results

Sample Demographics

The final sample consisted of 23 physicians: 16 (70%) cardiologists (including general [n=10], electrophysiologists [n=3], and AHF specialists [n=3]) and 7 (30%) PCPs (Table 1). 22% of physicians were female and 30% practiced in rural environments. The mean age was 49.7 years, and about half had been practicing for over 20 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristics |

Full Sample N (%) |

Cardiologists | Primary Care Physician |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 23 | 16 (70%) | 7 (30%) |

| Age | |||

| 30–39 y | 5 (22%) | 4 (25%) | 1 (14%) |

| 40–49 y | 6 (26%) | 4 (25%) | 2 (29%) |

| 50–59 y | 7 (30%) | 6 (38%) | 1 (14%) |

| 60–69 y | 5 (22%) | 2 (13%) | 3 (43%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 18 (78%) | 12 (75%) | 6 (86%) |

| Female | 5 (22%) | 4 (25%) | 1 (14%) |

| Practice location | |||

| Urban | 6 (26%) | 1 (6%) | 5 (71%) |

| Rural | 7 (30%) | 5 (31%) | 2 (29%) |

| Mixed, mostly urban | 10 (44%) | 10 (63%) | 0 |

| Years in practice | |||

| ≤5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6–10 | 5 (22%) | 3 (19%) | 2 (29%) |

| 11–15 | 4 (17%) | 4 (25%) | 0 |

| 16–20 | 2 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (14%) |

| ≥21 | 12 (52%) | 8 (50%) | 4 (57%) |

| Type of cardiologist | |||

| General | 10 (63%) | ||

| Electrophysiology | 3 (19%) | ||

| Heart failure specialist | 3 (19%) | ||

Themes

Characteristics of High‐Quality EOL Care

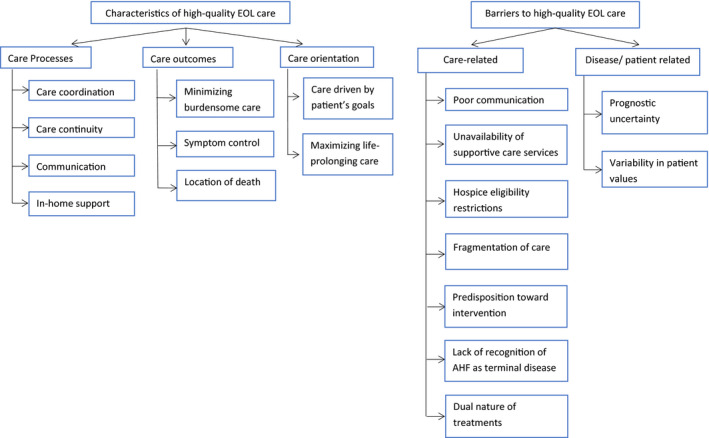

We organized elements of high‐quality EOL care into 3 categories: care processes, care outcomes, and care orientation (Figure 1 and Table 2). Rural and urban physicians largely agreed on the characteristics of high‐quality care.

Figure 1. Conceptual model for characteristics and barriers to high‐quality EOL care for patients with AHF.

AHF indicates advanced heart failure; and EOL, end‐of‐life.

Table 2.

Characteristics of High‐Quality Care*

| Theme | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Processes of care | |

| Care coordination | “High‐quality care is, I would say that there’s clarity of, ‐ like there’s a point person managing medications, so that there’s not any discord about who should the patient be going to or turning to if they’re having symptoms. So I would vote, I think the higher quality care is provided by a single team with single decision makers, that sort of thing, because as soon as patients think well should I go to this doctor for this or this doctor for this? I think they don’t know who to turn to. So the more shuffling around they have to do to get the assistance they need, I think the more stressful it is for them.” (PCP5U) |

| “My patients can’t go right back to see the cardiologist and so I’m left with the job of managing their congestive heart failure more than say if they were closer.” (PCP6R) | |

| Continuity of care | “So, to me the primary cardiologist often is the one that’s most responsible [for ensuring high‐quality care]. So that’s where the discussion should occur with the patient. And that’s the person that should waive off procedures, you know, EP docs, ICDs, you know the stuff that goes on here.” (CARD1U) |

| “… you know I espouse the belief that a good relationship with a patient that’s been developed over however many years goes a long way to having honest conversation about the person’s actual prognosis and nearing end‐of‐life” (PCP5U) | |

| Communication | “These [EOL] conversations really have to happen, and if [they don’t] then the patient could be set up for the classic sort of in and out of the hospital. Hopefully not in and out of the ICU or in places where they don’t really want to be, and if someone had a good conversation with them that they wouldn’t have ended up there. Meaning like in the ICU or tethered to IV diuretic in the hospital, or whatever.” (PCP5U) |

| “Usually the reason that [the end‐of‐life period goes poorly] is that patients or their families have unrealistic expectations or don’t really understand how ill patients are. I think if you’re unable to make that transition with them in their thinking that’s when the outcomes become worse” (CARD‐HF1U) | |

| In‐home support | “[High quality is] being able to be at home with family rather than hospitalized or at a skilled nursing facility … And so [when I think of high quality] I think about frequent contact with the patient at home. Visiting nurses coming with frequency to the home; helping people with the medications; adjusting medications as needed based on symptoms and physical exam findings.” (CARD 8R) |

| “[Rurality impacts quality EOL experience because] when it comes to like … home services, with weather road conditions, that absolutely impacts some of the services that are delivered. Some patients don’t have stable phone lines, which then takes out tele‐health and things like that. So it’s definitely more of a challenge.” (CARD5R) | |

| “Sometimes it’s just little things that they really appreciate. Somebody who gets a home concentrator for their oxygen changes their life… like making their day‐to‐day life meaningful and manageable, which is usually in part a lot of practical stuff. Like the right kind of wheel chair, and making sure that somebody checks on them every other day and all that stuff.” (CARD7R) | |

| Outcomes of care | |

| Minimizing burdensome care | “[High quality EOL care is] not necessarily all – pulling out all the stops, doing everything possible, but sort of making it so the patient is sort of well taken care of … but that it’s not necessarily like all of the expensive high quality medical interventions, but more of the things to sort of make them have the highest quality at the end of their life in terms of fewest symptoms.” (PCP2U) |

| “In some ways it’s easier to [avoid aggressive care in a rural] community, than it is in a ‘big city, big hospital environment,’ particularly if you know the patients and families … It’s … difficult to get patients to go for advanced therapies like LVADs or internal defibrillators, bi‐v pacing … But to get ‘em to go to [the city] to die is not exactly at the top of all people’s wish list.” (CARD 9R) | |

| Symptom control | “… and really, that they would want to just be comfortable and not be in any pain and not be in any distress with their breathing.”(CARD6U) |

| “…able to manage their symptoms in a timely manner that sort of takes away the stress of the family,” (CARD‐HF3U) | |

| Location of death | “[E]veryone wants to die at home with their family by their side” (PCP7R); |

| “[M]ost patients … want to be in their own house surrounded by their family and friends.” (CARD6U) | |

| “Dying at home is very hard. It’s very hard for the family. And at times does not fully probably optimize symptom management the way they can in a specific dedicated hospice care facility or occasionally in the hospital. I don’t know that the hospital is best necessarily either. But I think it’s extremely variable. So I think people would prefer at least to not die in the hospital and they would rather die at home, but I think we don’t have,‐ we’re not optimally equipped to do that. There’s a real lack of,‐ we do it pretty well, but it’s not great.” (PCP3U) | |

| Orientation of care | |

| Care driven by patient’s goals | “[High quality end‐of‐life care is] patient‐driven all the time assuming the patient is competent to make those decisions, and has a full understanding of what’s going on and what the implications are. I freely make recommendations to patients, but I emphasize that they’re recommendations, that they’re in the driver’s seat.” (CARD9R) |

| “… a well‐informed patient … will drive what we do. That [we should do] anything that is potentially medically reasonable even if reasonable means a low probability that it will work.” (CARD‐EP2U) | |

| Maximizing life‐prolonging care | “[Patients] want to know that everything possible is being done. And they feel as if going home is like people giving up.” (CARD6U) |

| “I would say that [high quality care is] they have had every opportunity to have had a work up done, medically. And treatment that has been fully optimized, meaning that this is the best that medically any physician or physician team can do for the patient and they’ve failed. Or if not failed, but the patient has not responded to that therapy.” (CARD‐HF2U) | |

| “…no one likes to get angry phone calls or be sort of accused of not taking the best care of their loved one, or giving up on them. It’s that dance around giving up, the perception of giving up on them when you start talking about end‐of‐life in hospice and that sort of thing.” (PCP5U) | |

| “[Rurality impacts the ability to achieve a quality EOL experience because] it limits some of the patients in regards to what can be offered to them. So someone who’s living in the backwoods of me, an hour north of us, not in close proximity to [the city academic medical center] will have, you tell them “I’d like you to think about a transplant evaluation or an LVAD, or this, to be seen in the heart failure clinic … some of these folks, they say, ‘It’s gonna take me an hour to drive [to the city] I don’t want to go there 5 times in a month.’ And they’ll actually give up what they might have for care because they don’t want to drive that far. That’s hard.” (CARD10R) | |

CARD indicates cardiologist; EOL, end of life; EP, electrophysiologist; HF, heart failure specialist; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; ICU, intensive care unit; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; PCP, primary care physician; R, physician practicing in rural environment; and U, physician practicing in urban environment.

Type of physician indicated after each quote.

Care processes

Physicians identified care coordination, care continuity, communication, and in‐home support (Table 2) as essential processes of care. Regarding coordination, physicians emphasized the need for clear delineation of who is responsible for various care tasks. Several PCPs noted that a rural environment made coordination a priority because of the heavy reliance on PCPs for patient care. A rural PCP explained: “My patients can’t go right back to see the cardiologist and so I’m left with the job of managing their congestive heart failure more than say if they were closer” PCP6R. In contrast, 1 cardiologist described a lack of physicians in rural areas creating an increase in reliance on cardiology: “… in these rural areas, there are … a bunch of sort of mid‐level, and I would say with respect, … not that well trained people trying to do heroic work with limited resources and not a great education. So if you are [an] advanced heart failure [patient], that is cardiology’s problem, I think” CARD2U. Additionally, rural and urban physicians suggested that the doctor who knew the patient best should be the primary orchestrator of EOL care and was most likely to forego burdensome care.

Both rural and urban participants described a need for communication as another important characteristic; they noted a need for discussing prognosis, individual values, and goals of care. Furthermore, multiple physicians attributed overly aggressive, nonbeneficial care to communication failures. Many participants also noted the necessity of home care, often by hospice, to titrate medications and provide emotional support for patients and families. Physicians described rural patients as having an increased need for paid in‐home care because of lower socioeconomic status and decreased family support, stating “people can wind up like geographically separated from family, due to the resource issue [in rural environments]” CARD4U.

Care Outcomes

Physicians identified several key elements related to care outcomes: minimizing burdensome care, symptom control, and patient‐preferred location of death (Table 2). One participant described the need to avoid procedures stating, “most procedures, I’m not sure that the risk versus potential benefit makes sense when someone is near end‐of‐life. I think less is more generally” (CARD8R). Another cardiologist explained the impact of providing aggressive care on his own feelings: “You start well intentioned to do one thing and it leads to another and another and the patient doesn’t survive our attempts. And so now we’ve made the last weeks, months of a patient’s life kind of in intensive care units having procedures. And that never feels good” (CARD1U). Several rural physicians noted rurality as a facilitator for avoiding excessive interventions, noting that some rural patients “don’t want to go anyplace outside their home community … it’s sometimes even difficult to get patients to go for advanced therapies like LVADs or internal defibrillators, bi‐v pacing. Sometimes it’s tough to convince people to go there” (CARD9R). Good symptom control, both psychological and physical, was emphasized by rural and urban physicians. One of the heart failure providers described how rurality makes symptom management challenging: “Having the patients far away from me in particular makes it more difficult to manage their fluid and manage their symptoms, so yes, I think the rurality certainly does make a difference” (CARD‐HF1U). Most participants identified dying at home as a key outcome measure for high‐quality care; however, some physicians acknowledged that death in the hospital may be “the right place for the family” (CARD2U). Physicians noted a lack of homecare services as a barrier disproportionately affecting rural patients wishing to die at home (see barriers).

Orientation of care

We found 2 themes related to care orientation: Care should be driven by patients’ individual goals and physicians should maximize life‐prolonging care (Figure 1 and Table 2). Rural and urban physicians alike emphasized the need for goal‐directed care; several participants felt that even interventions with a low likelihood of success were appropriate if they were consistent with patients' preferences. In potential conflict with goal‐directed care and the avoidance of burdensome care at EOL, however, cardiology providers endorsed a belief in exhausting all potential life‐prolonging interventions. Providers expressed reluctance to designate patients as EOL until there were no medical treatments to offer, a move that effectively shortened the EOL time period. As 1 participant put it: “I made it clear to them that I think we were kind of at the end of what we could do. And … the patient passed away within 24‐48 hours of making that decision … That is kind of an ideal and again, we’re talking about [EOL as] the last days to weeks” (CARD1U). Rural providers had a similar need to maximize available aggressive therapies, and described negative feelings if patients could not receive them: “They’ll actually give up what they might have for care because they don’t want to drive that far. That’s hard” (CARD10R). Many participants attributed their desire to exhaust aggressive options to a perceived patient need. Others believed that failure of aggressive therapies helped patients and families accept a poor prognosis.

Barriers to High‐Quality EOL Care

We categorized identified barriers to high‐quality EOL care into care‐related factors and disease/patient factors (Figure 1, Table 3). Participants identified several challenges that disproportionately affected quality of EOL care for rural patients.

Table 3.

Themes Around Barriers to High‐Quality EOL Care*

| Theme | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Care‐related factors | |

| Systemic barriers to communication | “Most people that are with advanced heart failure, they have many comorbidities a lot of times and it’s very … complicated. So to take time to have a conversation about goals of care … I just think that a lot of times that doesn’t get prioritized at the time that maybe it should have in retrospect … and it really requires a lot of effort and it requires time to do it properly. And it’s difficult to do that in the clinic when you have a 15 minute appointment and you have 20 patients to see.” (CARD8R) |

| “But I don’t feel like … I was trained well to have [conversations] because we were sort of trained well to … try to fix the problem and [move] on, you know?” (PCP5U) | |

| “End‐of‐life decisions, there’s gotta be some preparation for that and none of us really like to talk about it because it’s not a pleasant topic.” (CARD‐EP3U) | |

| Unavailability of supportive care services | “[Rurality impacts quality EOL experience because] when it comes to like … home services, with weather road conditions, that absolutely impacts some of the services that are delivered… So it’s definitely more of a challenge.” (CARD5R) |

| “[M]y ideal service would be if a nurse could come into a home, assess a patient, and if they needed some IV Lae for comfort to help someone breathe, they would be able to kind of give a shot of IV Lasix at home [so] that they didn’t have to come to the Emergency Room.” (CARD10R) | |

| “Yeah it’s definitely tricky I think, for patients in terms of a quality end‐of‐life because the resources [are less in rural environments] whether that be home care, getting to see – even into a practice to see their doctor. And so that can be really tricky. And obviously we have some hospice locations, but again those are sometimes far away for patients as well.” (PCP2U) | |

| Hospice restrictions on palliative interventions | “The only other correspondences I’ll have with a hospice nurse are, ‘No, I can’t draw blood,' or, ‘No, I can’t give IV drugs at home.’ In terms of, I feel like IV Lasix to a CHF patient is like IV morphine to a cancer patient. And it provides comfort. (CARD10R) |

| Palliative care involvement increases fragmentation of EOL care | “[A] palliative care consultation in which they have to go someplace sometimes just adds another consultation for them when they’re already trying to navigate sometimes three specialists including myself. So to throw in a palliative care consultation, it seems to me that sometimes I’m adding an additional burden to them.” (PCP5U) |

| “[The problem with palliative care is that] some of the providers can feel stepped on. They want to be controlling the clinical care.” (CARD‐EP2U) | |

| Predisposition toward intervention | “You start well‐intentioned to do one thing and it leads to another and another and the patient doesn’t survive our attempts. And so now we’ve made the last weeks, months of a patient’s life kind of in intensive care units having procedures.” (CARD1U) |

| “Most as I’m thinking about that had a more aggressive approach [at end‐of‐life]. Most of it is because we didn’t necessarily think it was the end. And when we’re not sure we continue to treat aggressively and despite those aggressive management techniques, tactics, the patient expired.” (CARD1U) | |

| Lack of recognition of AHF as terminal disease | “[T]here’s a cultural acceptance that not every cancer is curable. There’s a cultural acceptance that end stage lung disease is end stage lung disease. I feel like culturally with heart disease that people kind of expect this is fixable or you’re giving up.” (CARD‐EP2U) |

| “And part of that I think is the idea that we can fix everything. There’s always a new procedure that can be done as opposed to oncology where you actually run out of things you can do. In cardiology, there’s always this perception that there’s one more thing you can try.” (PCP7R) | |

| Dual nature of treatments: disease modifying and palliative | “Let’s say that you have someone with end‐stage heart failure who goes into atrial fibrillation and they start to get a lot worse. I would cardiovert that patient. Let’s say there’s a patient who’s got end‐stage heart failure and their heart rate is too slow, and they can’t stand up without falling over. I’m going to put a pacemaker in that patient… they draw a lot of comparisons between cardiology and oncology when they talk about palliative care and hospice, [but] they’ll withdraw chemotherapy and go on hospice. We don’t ever really withdraw our medications.” (CARD10R) |

|

“So we have for example, Bi v pacemakers … They’re better at relieving symptoms than Morphine is. So I think things like that are potentially appropriate for someone otherwise seeming like an end‐of‐life patient.” (CARD‐EP2U) “A hospitalization is not a defeat… I know plenty of patients that don’t mind coming in if it means that they might feel a little better.” (CARD‐HF3U) |

|

| “I think things like heart catheterization would be appropriate [at end‐of‐life], left‐heart catheterization if there is something that’s amenable for an intervention for symptom relief.” (CARD5R) | |

| Disease/patient factors | |

| Prognostic uncertainty | “I think it’s oftentimes hard to predict which one of those decompensations may be the one where they don’t really bounce back.”(CARD‐HF3U) |

| “I think the statistics aren’t as clear cut as they are for example with cancer or various other things like that, at least in my experience.”(CARD3U) | |

| “… the challenge is the same as any exercise you go through where you’re trying to apply data from a study to an individual, right? So studies are done on populations. And we manage individuals, so I guess that’s that the challenge of translating study data from populations that allow us to have a handle on prognosis of the individual patient.” (CARD4U) | |

| Variability in patient values | “I think high quality end‐of‐life care is care that matches what the patient wants. And I think the hard part is that really varies from patient to patient. So some patients like being in the hospital. … They’re lonely at home and they’re elderly and so having,‐ for some patients probably for them high quality means being in the safety of a beeping monitor that tells them that they’re still alive. Whereas some patients, high quality is going to mean ‐ I’m at home, I die at home with my family around me, I minimize my interaction with the health.” (PCP1U) |

| “Well, I don’t know if there’s a good measure. I think at the end of the day, what defines high quality in my mind is if the patient and family are satisfied that the care that they received was within the wishes that they would have wanted. And that again can be fairly individualistic… I think for quality measures, that’s a tough thing.” (CARD‐EP3U) | |

CARD indicates cardiologist; CHF, congestive heart failure; EOL, end of life; EP, electrophysiologist; HF, heart failure specialist; PCP, primary care physician; R, physician practicing in rural environment; and U, physician practicing in urban environment.

Type of physician indicated after each quote.

Care‐related factors

We identified multiple care‐related barriers to high‐quality care (Table 3). The first subtheme was systemic barriers to communication. Both rural and urban participants attributed poor communication to time scarcity, inadequate training, low confidence, and aversion to difficult conversations. Participants explained that the increased comorbidity burden of patients with heart failure made EOL conversations more challenging to prioritize among the demands of managing complex medical conditions.

Physicians also cited issues of unavailability of supportive care services. Participants referenced challenges of providing intravenous diuretic therapy at home. Participants viewed the lack of services, in home and inpatient hospice settings, as particularly challenging in rural environments. One primary care physician described, “It’s definitely tricky, I think for [rural] patients in terms of a quality end‐of‐life, because getting the resources like whether that be home care … [or] even into a practice to see their doctor. A lot of [rural] patients live far away and travel a long ways … and so that can be really tricky. And obviously we have some hospice locations, but again those are sometimes far away for patients as well” (PCP2U). Other physicians also described geographical separation, lower socioeconomic statuses, and lack of transportation as barriers disproportionately affecting rural patients.

Hospice eligibility restrictions was another subtheme. Physicians perceived the Hospice Medicare benefit rules as antithetical to providing high‐quality EOL care. Specifically, they struggled with the inability to provide intravenous diuretics or continuous inotropic support while on hospice. Physicians also noted the need for a single qualifying terminal diagnosis as a barrier for patients with AHF because the cause of death is due to multimorbidity.

Although many participants felt involving palliative care teams is beneficial, some felt that additional providers increases fragmentation of care and may be burdensome for patients, who already see many specialists. Other providers believed that involving palliative care clinicians may reduce their control over patient care. Several rural providers noted lacking access to palliative medicine, 1 physician explained: “Where I practice in rural Maine … I’m not sure I’ve ever directly interacted with a palliative care specialist … it’s an availability thing. They just aren’t available here” (PCP7R).

Another care‐related barrier was a perception that our medical system has a predisposition toward intervention. One physician described this predisposition using LVADs as an example: “and we’re offering these advanced platforms like they’re magic. And they’re incredibly over‐marketed by hospitals that want to put them in. So you’re sitting in the matrix of marketing, right, multi‐tens of thousands of dollar device going in, for what? It’s oversold” (CARD2U). Primary care physicians also described this predisposition theme as an important factor affecting EOL care, though they attributed it to cardiologists. Another physician related a case where the patient “was sent to I think their third transplant center for evaluation, and then a fourth one … we extended suffering by doing that” (CARD‐HF1U). Physicians recognized that pursuing aggressive treatment prevents patients from engaging in more meaningful activities, such as time with family. Several providers felt that a bias toward interventions, combined with prognostic uncertainty, explained why some patients with AHF receive overly aggressive EOL care. Although rural physicians noted that their patients were less likely to undergo interventions because of travel requirements (see quote about maximizing life‐prolonging care in Table 2), they perceived this propensity as a harm rather than a benefit—suggesting that rural cardiologists are also predisposed toward intervention. Physicians identified lack of recognition of AHF as a terminal disease by patients in both rural and urban settings as a care‐related barrier and described how it delays transitions from purely cure‐focused to comfort‐focused care. Participants attributed this lack of recognition to our society and felt it was exacerbated by the culture of cardiology.

The final care‐related barrier shared by urban and rural physicians was a perception that AHF treatment is unique in the dual nature of treatments; many of the disease‐modifying treatments, such as diuretics and inotropic support, are also palliative—that is, they also make patients feel better. Several physicians felt that invasive procedures, such as biventricular pacers and cardioversion, were indicated during EOL because of their symptomatic benefits. Physicians recognized positive and negative impact of the conceptual overlap in the goals of therapies. On the positive side, the overlap encouraged continued involvement of cardiologists in EOL care. However, there may be hesitation to refer patients to palliative and hospice care, because hospice admission would limit access to symptom‐palliating IV diuretics or inotropic therapy. Other physicians noted the overlap is a barrier to prognostic conversations because patients aware of a poor prognosis might be less vigilant about their volume status, ultimately causing unmanaged symptoms.

Disease/patient factors

Rural and urban participants described 2 subthemes categorized into disease/patient factors: prognostic uncertainty and variability in patient values. Physicians noted the disease trajectory of AHF, marked by multiple exacerbations with recovery, makes it challenging to identify EOL. Many reported prognostic uncertainty was greater in heart failure than in other diseases. Uncertainty was attributed to multiple causes: lack of reliable models, decreased confidence in model accuracy, challenges applying population‐based models to individuals, and prior errors in prognostication decreasing ability to rely on risk estimates. Providers described offering aggressive interventions more frequently when there was prognostic uncertainty. Although most participants reported struggling with prognosticating, a few believed they were able to prognosticate with a high level of precision. Notably, multiple providers reported distress resulting from prognostic uncertainty.

Providers also noted a variability in patient values as a barrier to high‐quality care. Some providers believed that patients may not understand their own values and that providers must be skilled to elicit them. Some providers perceived that variation in values was greater for patients with AHF than for other populations. For example, physicians believed that patients with AHF felt better after hospitalizations, they were more accepting of being hospitalized. In addition to creating care challenges for individual patients, physicians felt the variation in values was a critical barrier to developing universal quality measures.

Discussion

This study used rigorous qualitative methods to explore essential elements of, and barriers to, high‐quality EOL care in patients with AHF. We identified several barriers similar to those found in studies about inclusion of palliative medicine for patients with AHF. 34 , 35 To our knowledge, however, this is the first study addressing how these and other barriers affect quality of EOL care. Our findings have important implications for developing quality indicators for patients with AHF.

Several identified elements of high‐quality EOL care for patients with AHF resembled established quality indicators for patients with cancer: dying at home, receiving adequate in‐home support, and good symptom control. Participants endorsed the need to avoid overly aggressive care; however, many cardiologists simultaneously expressed ambivalence towards life‐prolonging interventions—a finding that, to our knowledge, has not been previously documented. Prior qualitative studies with physicians have characterized the culture of cardiology as being biased toward aggressive care, 35 , 36 such that transitions to palliative or comfort‐oriented care are indicative of defeat or failure. 34 , 36 The desire to exhaust interventions may explain observed low rates of goals of care conversations 37 and advance directive completion, 38 resistance to palliative care, 35 and late hospice admissions. 39 The predisposition toward aggressive care and the association of death with failure likely contributes to unnecessary moral distress.

Many physicians cited AHF’s high level of perceived prognostic uncertainty, relative to other diseases, as hindering high‐quality EOL care. 18 The heart failure trajectory is highly variable, likely increasing physician perception of uncertainty in prognostic estimates. Prior qualitative studies have identified this uncertainty as impeding prognostic conversations and the involvement of palliative care specialists. 27 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 40 , 41 A national survey found cardiology and primary care physicians did not feel confident in their ability to identify when a patient was in the last 6 months of life. 18 Our study highlights the importance of accounting for prognostic uncertainty in establishing standards for high‐quality EOL care for patients with AHF, compared with other disease conditions such as cancer. The high degree of prognostic uncertainty for patients with AHF may warrant relatively less stringent benchmarks for EOL care, as well as payment models that allow patients to concurrently receive disease‐directed therapy alongside treatments directed toward symptom palliation, quality of life, and preparation for potential death.

Similar to other qualitative studies, patients' lack of recognition of AHF as a terminal disease was recognized by our participants as a unique barrier for AHF patients. 19 , 21 , 26 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 One reason for this lack of awareness is the high level of multimorbidity in the AHF population, which fosters a belief that patients with AHF will die from other diseases, 19 and may lead patients and clinicians to discount the mortality risk of multimorbidity itself. Not recognizing heart failure as a terminal disease may exacerbate clinicians' and patients' avoidance of difficult conversations about prognosis and considerations of goals of care. 42

The final unique barrier identified by our study has been discussed in the literature 14 but not, to our knowledge, empirically documented: the overlap between disease‐modifying and symptom‐modifying therapies. Participants mentioned multiple therapies (eg, diuretics, inotropes, pacemakers, biventricular pacemakers, and cardioversion) as treatments that both modify the disease course and alleviate symptoms. This overlap has the potential to create hesitation in referring patients for palliative care because of an unclear role of palliative medicine in symptom management. 34 This reluctance regarding palliative care is problematic because, although therapies used by cardiologists may palliate dyspnea, they do not treat other symptoms, including depression, pain, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbances, which represent important sources of suffering for patients with AHF. 2 , 3 , 43 With regard to initiating hospice, some participants reported worrying that hospice referral would result in suboptimal management of fluid status. In fact, there is evidence that hospices may lack competence managing volume status and adequate understanding of the role of inotropes for comfort. 44 Hence, the overlap between disease‐modifying and symptom‐modifying therapies may impair hospice programs' ability to provide the most effective symptom management for patients.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate how rurality affects quality of EOL care for patients with AHF. The inclusion of rural providers increases the generalizability of quality metrics derived from our analysis. We found that rural and urban providers had similar views on the characteristic of, and barriers to, high‐quality care. However, rural providers perceived disparities in access to in‐home supports, an increase need for coordination of care, and a reliance on primary care providers for most EOL care delivered. Prior studies for other diseases support their perception of decreased access to hospice and in‐home care. 30 , 31 , 45 Rural physicians also noted that their more remote location resulted in fewer patients receiving aggressive interventions at EOL. Participants perceived this difference as both beneficial and a source of distress, reflecting conflicting desires to avoid invasive therapies at EOL and maximize life‐prolonging interventions.

Overall, these findings have several implications for the development of EOL care quality measures for patients with AHF. High‐quality EOL care for AHF and cancer are similar in some respects; however, perceptions of high prognostic uncertainty, along with a predisposition toward exhausting disease‐modifying therapies, makes it unlikely that cancer care benchmarks can be applied to AHF. Based on these distinctions and our study's other findings, we believe several problems must be addressed before developing indicators of high‐quality AHF EOL care. First, more research is needed to implement evidence‐based prognostic tools for patients with AHF. Risk prediction holds potential to individualize treatment decisions; however, there are gaps in our understanding of appropriate risk thresholds to drive clinical decisions. 46 Importantly, risk estimates derived from predictive models often require specific recalibration procedures to optimize performance for local populations 47 and guard against harm. 48 These limitations must be addressed before these tools can inform clinical decisions. Meanwhile, more research is needed to develop and test communication interventions that can help patients with AHF understand their prognosis and cope with prognostic uncertainty.

Our findings also suggest that EOL care quality measures for AHF should be patient‐centered and emphasize the receipt of goal‐concordant care and optimal symptom control (beyond dyspnea), rather than on utilizing aggressive care (eg, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, intensive care unit stays). The outcome from this study also has implications for healthcare policy. Payment models should be reformed to enable patients to receive concurrent disease‐directed therapies and maximal in‐home support. These models involve rethinking ethical priorities. Medicine generally adopts the principle of double effect to justify enacting symptom‐modifying interventions to relieve suffering, despite possibly shortening life. In the care of patients with AHF at EOL, however, this double effect is reversed: some available disease‐modifying interventions have the dual benefit of relieving suffering (eg, intravenous inotropes) but may not be pursued because they are perceived to be life prolonging. Concurrent delivery of disease‐directed care and comfort‐based care has been shown to be cost effective and helpful in decreasing burdensome care at EOL for patients with cancer 49 and should be studied for patients with AHF.

Notably, there are likely some indicators of high‐quality care that went unrecognized by our participants. Our participants did not raise caregiver burden and the need to include adequate support for caregivers as a quality metric. Additionally, participants did not discuss the potential benefits of using interdisciplinary team approaches to facilitate decision making regarding invasive procedures to reduce burdensome care. Finally, our participants discussed the need to control dyspnea and pain at EOL; however, other symptoms known to be prevalent in AHF went unmentioned.

Our study has several limitations. We interviewed physicians from a variety of backgrounds but did not include all types of physicians (eg, interventional cardiologists) or other interdisciplinary providers (eg, social workers or nurses) involved in the care of AHF. Although many disciplines contribute to the EOL care received by patients with AHF, physicians were the focus of this study because of their role as director of the interprofessional team. We also did not interview palliative medicine providers given the lack of palliative medicine specialists in rural areas. Patient and/or caregivers may have differing opinions of important elements of high‐quality EOL care and these opinions along with those of other specialists merit exploration in the future. Whether or not a patient is a candidate for heart transplant may influence how doctors define high‐quality EOL care; however, this factor was not explored and is another important focus for future research. Finally, our study sample was relatively small and limited to a single state; larger studies with more geographically diverse samples are needed to confirm our findings.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to empirically investigate the unique attributes of, and barriers to, high‐quality EOL care for patients with AHF. Although we found elements and barriers that are similar to other diseases' EOL care, our results affirm that identifying the EOL phase is a difficult and unique challenge for AHF because of 3 factors: increased prognostic uncertainty, failure to recognize AHF as a terminal disease, and conceptual overlap in symptom‐modifying and disease‐modifying therapies. Left unmodified, the challenges to identifying EOL combined with a culture that values exhausting life‐prolonging treatments will result in patients receiving overly burdensome care at EOL. This work emphasizes the need for further research to improve prognostication and measurement of value‐concordant care as well as the need for more flexible care approaches that do not require patients to forgo helpful treatments in order to receive hospice services and high quality EOL care.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by the Natalie V. Zucker Research Center for Women Scholars.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016505 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016505.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

This work was published in abstract form (Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2020; 60: 274.)

References

- 1. Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. More ‘malignant’than cancer? Five‐year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alpert CM, Smith MA, Hummel SL, Hummel EK. Symptom burden in heart failure: assessment, impact on outcomes, and management. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, Yamashita TE, Hutt E, Gottlieb SH, Dy SM, Kutner JS. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well‐being: a comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;592–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, Kutner JS, Peterson PN, Wittstein IS, Gottlieb SH, Yamashita TE, Fairclough DL, Dy SM. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2007;643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ, Block S. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end‐of‐life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;1133–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Weeks JC, Block SD, Grunfeld E, Ayanian JZ. Evaluating claims‐based indicators of the intensity of end‐of‐life cancer care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Quality Forum . National quality forum endorsed measures. Web site. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/QPSTool.aspx. Accessed March 9, 2018.

- 8. Fairfield KM, Murray KM, Wierman HR, Han PK, Hallen S, Miesfeldt S, Trimble EL, Warren JL, Earle CC. Disparities in hospice care among older women dying with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suero‐Abreu GA, Johnson CM, McKenna M, Wang JC, Barajas‐Ochoa A, De Silva P, Perez A, Zhong F, Srinivas S, Chang VT‐S. Assessment of end‐of‐life care quality indicators in veterans with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;1133–1138. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hutchinson RN, Lucas FL, Fairfield K. End‐of‐life healthcare use of medicare patients with melanoma based on patient characteristics and year of death. J Maine Med Cent. 2020;2. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hutchinson RN, Lucas FL, Becker M, Wierman HR, Fairfield KM. Variations in hospice utilization and length of stay for Medicare patients with melanoma. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;1165–1172.e1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morden NE, Chang C‐H, Jacobson JO, Berke EM, Bynum JP, Murray KM, Goodman DC. End‐of‐life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;786–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miesfeldt S, Murray K, Lucas L, Chang C‐H, Goodman D, Morden NE. Association of age, gender, and race with intensity of end‐of‐life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2012;548–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warraich HJ, Meier DE. Serious‐illness care 2.0—meeting the needs of patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;2492–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haydar ZR, Lowe AJ, Kahveci KL, Weatherford W, Finucane T. Differences in end‐of‐life preferences between congestive heart failure and dementia in a medical house calls program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Formiga F, Chivite D, Ortega C, Casas S, Ramon JM, Pujol R. End‐of‐life preferences in elderly patients admitted for heart failure. QJM. 2004;803–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gelfman LP, Barrón Y, Moore S, Murtaugh CM, Lala A, Aldridge MD, Goldstein NE. Predictors of hospice enrollment for patients with advanced heart failure and effects on health care use. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;780–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hauptman PJ, Swindle J, Hussain Z, Biener L, Burroughs TE. Physician attitudes toward end‐stage heart failure: a national survey. Am J Med. 2008;127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Momen NC, Barclay SI. Addressing ‘the elephant on the table’: barriers to end of life care conversations in heart failure–a literature review and narrative synthesis. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2011;312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poole‐Wilson PA, Uretsky BF, Thygesen K, Cleland JG, Massie BM, Ryden L. Mode of death in heart failure: findings from the ATLAS trial. Heart. 2003;42–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O’Donnell AE, Schaefer KG, Stevenson LW, DeVoe K, Walsh K, Mehra MR, Desai AS. Social Worker‐Aided Palliative Care Intervention in High‐risk Patients With Heart Failure (SWAP‐HF): a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;516–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klindtworth K, Oster P, Hager K, Krause O, Bleidorn J, Schneider N. Living with and dying from advanced heart failure: understanding the needs of older patients at the end of life. BMC Geriatr. 2015;125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, Levy WC, Tulsky JA, Bowers MT, Dodson GC, O'Connor CM, Felker GM. Discordance between patient‐predicted and model‐predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2008;2533–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kendall M, Carduff E, Lloyd A, Kimbell B, Cavers D, Buckingham S, Boyd K, Grant L, Worth A, Pinnock H, et al. Different experiences and goals in different advanced diseases: comparing serial interviews with patients with cancer, organ failure, or frailty and their family and professional carers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hjelmfors L, Sandgren A, Stromberg A, Martensson J, Jaarsma T, Friedrichsen M. "I was told that I would not die from heart failure": patient perceptions of prognosis communication. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fang JC. Rise of the machines—left ventricular assist devices as permanent therapy for advanced heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2009;2282–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, Coady E, Hazeldine C, Walton M, Gibbs L, Higginson IJ. Improving end‐of‐life care for patients with chronic heart failure: "Let's hope it'll get better, when I know in my heart of hearts it won't". Heart. 2007;963–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang H, Qiu F, Boilesen E, Nayar P, Lander L, Watkins K, Watanabe‐Galloway S. Rural‐urban differences in costs of end‐of‐life care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Rural Health. 2016;353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waldrop D, Kirkendall AM. Rural–urban differences in end‐of‐life care: implications for practice. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;263–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rainsford S, MacLeod RD, Glasgow NJ, Phillips CB, Wiles RB, Wilson DM. Rural end‐of‐life care from the experiences and perspectives of patients and family caregivers: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2017;895–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Madigan EA, Wiencek CA, Vander Schrier AL. Patterns of community‐based end‐of‐life care in rural areas of the United States. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2009;71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. MaxQDA 2020 . VERBI Software.Web site. Available at: maxqda.com. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 33. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, Dev S, Biddle AK, Reeve BB, Abernethy AP, Weinberger M. “Not the ‘grim reaper service’”: an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;e000544 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Siouta N, Clement P, Aertgeerts B, Van Beek K, Menten J. Professionals' perceptions and current practices of integrated palliative care in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study in Belgium. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Green E, Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C. Exploring the extent of communication surrounding transitions to palliative care in heart failure: the perspectives of health care professionals. J Palliat Care. 2011;107–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldstein NE, Mather H, McKendrick K, Gelfman LP, Hutchinson MD, Lampert R, Lipman HI, Matlock DD, Strand JJ, Swetz KM. Improving communication in heart failure patient care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;1682–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Butler J, Binney Z, Kalogeropoulos A, Owen M, Clevenger C, Gunter D, Georgiopoulou V, Quest T. Advance directives among hospitalized patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;112–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aldridge MD, Bradley EH. Epidemiology and patterns of care at the end of life: rising complexity, shifts in care patterns and sites of death. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, May C, Ward C, Capewell S, Litva A, Corcoran G. Doctors' perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: focus group study. BMJ. 2002;581–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harding R, Selman L, Beynon T, Hodson F, Coady E, Read C, Walton M, Gibbs L, Higginson IJ. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, Coady E, Hazeldine C, Walton M, Gibbs L, Higginson IJ. Improving end‐of‐life care for patients with chronic heart failure:“Let’s hope it’ll get better, when I know in my heart of hearts it won’t”. Heart. 2007;963–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Allen LA, Shakar S, Kutner JS, Matlock DD. Outpatient palliative care for chronic heart failure: a case series. J. Palliat Med. 2011;815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goodlin SJ, Kutner JS, Connor SR, Ryndes T, Houser J, Hauptman PJ. Hospice care for heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watanabe‐Galloway S, Zhang W, Watkins K, Islam K, Nayar P, Boilesen E, Lander L, Wang H, Qiu F. Quality of end‐of‐life care among rural Medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer. J Rural Health. 2014;397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, Granger BB, Steinhauser KE, Fiuzat M, Adams PA, Speck A, Johnson KS, Krishnamoorthy A. Palliative care in heart failure: the PAL‐HF randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wessler BS, Ruthazer R, Udelson JE, Gheorghiade M, Zannad F, Maggioni A, Konstam MA, Kent DM. Regional validation and recalibration of clinical predictive models for patients with acute heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;e006121 10.1161/JAHA.117.006121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Van Calster B, Vickers AJ. Calibration of risk prediction models: impact on decision‐analytic performance. Med Decis Making. 2015;162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mor V, Wagner TH, Levy C, Ersek M, Miller SC, Gidwani‐Marszowski R, Joyce N, Faricy‐Anderson K, Corneau EA, Lorenz K. Association of expanded VA hospice care with aggressive care and cost for veterans with advanced lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;810–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1