Abstract

360-degree video recorded in fires provides a unique perspective that allows the viewer to change the viewing direction as regions of interest change during a fire. Use of 360-degree and traditional cameras at some locations in intense fires for extended durations has been hampered in the past by the high levels of radiant heat flux that will damage the camera’s imaging sensor. This paper describes how a thin layer of moving water can be used to significantly reduce unwanted infrared radiation generated by a fire while allowing visual imaging using a simple and inexpensive enclosure. Essential details to replicate this system are provided and three illustrative example deployments are discussed.

Keywords: 360-degree video, fire, instrumentation, virtual reality

1. Introduction

As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Videos and images enable compelling technical storytelling and can quickly convey the significance of events and complex physical phenomena in ways that the most elegant prose or brilliantly depicted numerical data often cannot. Occasionally, images stand on their own; they are the data and the message. Frequently, images provide the context to understand the data being communicated.

Fire science lends itself to imaged-based data, in particular video, because it frequently deals with spatially-distributed phenomena that vary with time as a fire grows and decays. The objective of this work is twofold. First, to thermally protect cameras to allow them to record video in the middle of intense fires for indefinite durations and, second, to take advantage of recent developments in omnidirectional (360-degree) camera technologies. By using 360-degree video, as opposed to cameras with a limited directional field of view, the viewer can focus on changing regions of interest and can watch video footage in immersive viewing environments such as a virtual reality head-mounted display or in room-scale virtual environments.

Placing cameras into fires is not new. Video and photography have long been used as primary measurement tools for fire detection [1] and in the study of flaming combustion; e.g., [2-4]. In large-scale compartment fire experiments [5-7] video is nearly always recorded and there has been widespread use of video in the study of wildland fire [8,9]. What is new about the present work is that it significantly improves the tenability of video cameras inside of severe fires in an inexpensive and robust way. In addition to resolving the obvious need to keep a camera from overheating in a fire, the solution significantly reduces the intense infrared radiation generated by the fire that would quickly damage the camera’s imaging sensor when it is close to a fire.

This paper describes the concept design for an enclosure to house 360-degree video cameras, provides the essential fabrication details necessary to replicate the system and shows select applications of the system that illustrate its strengths and weaknesses. This paper should be of value to fire scientists and others interested in capturing better video footage of fires.

2. Concept design

In fire research it is often desired to place cameras, or other optical instruments, close to a fire or another heat source (e.g., radiant panel or gas furnace) where high ambient temperatures exist. In these situations, air cooling systems or liquid (usually water) cooled metallic enclosures are often employed to protect the camera from overheating. Numerous examples of custom-built and commercially-available [10,11] systems can be found.

In the extreme case of a fully-developed compartment fire, however, air temperatures can exceed 800 °C even near the floor of the compartment, and, more importantly, heat flux intensities inside the compartment can be greater than 150 kW/m2 [12-14]. Fig. 1 shows a snapshot from video footage taken just outside of the doorway opening of a fully-developed furnished compartment fire 17 min after ignition when the heat release rate (HRR) was 10 MW. Heat fluxes measured 1.8 m above the floor along the wall of the compartment over 200 kW/m2 were sustained for over 10 min [13]. For comparison, solar radiation reaching the surface of the earth on a clear day is about 1 kW/m2 and heat flux of 15 kW/m2 has been shown to melt a hole through polycarbonate self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) facepieces in less than 5 min [15]. Even if a camera is protected from overheating in such an environment, heat flux at the levels observed in a compartment fire would rapidly (in seconds) destroy the camera’s imaging sensor. Therefore, the radiant heat flux must be significantly reduced to record video.

Fig. 1.

Snapshot from video footage taken outside of the doorway opening of a fully-developed furnished compartment fire extracted from [16].

The radiative energy produced by a hydrocarbon fire, which is often quantified in terms of heat flux, comes primarily from spectral emissions produced by the change in energy state of molecules during combustion, largely carbon dioxide and water, and from black-body radiation emitted by heated soot particles. The schematic illustration in Fig. 2 emphasizes that the majority of this radiative energy (defined as the area under the curve) is in the infrared (IR) portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, with smaller portions in the visible (VIS) and ultraviolet (UV) portions of the spectrum. In the case of video cameras, one wants to preserve energy at visible wavelengths, while blocking energy at infrared (and to a small extent ultraviolet) wavelengths.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of relative intensity spectrum of a typical hydrocarbon fire.

For low-levels of heat flux, anti-reflective (AR) coated glass filters can be used to reduce unwanted radiant energy. However, at higher levels of heat flux, AR coated filters will not sufficiently reduce the undesired radiation and the coatings may be prone to thermal damage. Here, we are aided by nature. Water is extremely good at absorbing energy in the infrared spectrum while transmitting energy in the visible spectrum. This is illustrated in Fig. 3 by a measured transmittance spectrum for pure water. As water absorbs the energy emitted by the fire, it is heated. The hot water can be transported away and replaced with cool water providing a filter and heat exchanger that can survive for an indefinite time. These properties make water a good low-pass filter for visible spectrum cameras exposed to intense fires.

Fig. 3.

Relative transmittance spectrum for a 30 mm thick sheet of deionized water.

The electromagnetic radiation absorption, i.e., filtering, characteristics of liquid water can be affected (or intentionally modified) by many factors [17] including temperature, impurities in the water, as well by the thickness of the water sheet. The efficacy of tap water to absorb the broadband radiation emitted by a hydrocarbon fire was determined empirically. Exploratory experiments showed that the radiant energy produced by a natural gas diffusion flame could be reduced from 100 kW/m2 to less than 1 kW/m2 behind a 30 mm thick sheet of tap water. This insight was first used to protect distance measurement lasers [18] from thermal radiation in ‘dry’ systems, where the measurement instrument was placed behind a moving sheet of water, and subsequently in ‘wet’ systems with traditional, i.e., not 360-degree, video cameras, where the camera was placed in the water in a waterproof enclosure. The advantage of a ‘wet’ system over a ‘dry’ system is that the water serves the dual purpose of cooling the camera.

Fig. 4 shows a concept sketch of the extension of the ‘wet’ system to a 360-degree camera. The design has been implemented with various monoscopic 360-degree cameras, which provide flat, spherical projections, but could potentially be adapted for use with stereoscopic cameras that also provide depth information. Several waterproof sports action 360-degree cameras are commercially available for under 800 USD and products are rapidly getting better, cheaper, and smaller. The 360-degree camera is placed at the center of a transparent globe made of temperature-resistant glass. The glass dome is clamped to a pipe flange and made watertight with a temperature-resistant silicon O-ring. A ceramic fabric gasket is placed between the clamping ring and the glass dome to reduce stress concentrations and the chance of cracking the dome. The pipe flange has a diaphragm at its center with two holes and is connected to a threaded pipe. The holes allow for water to flow into and out of the dome. The outflow hole in the diaphragm is connected to a flexible tube with a diameter smaller than that of the threaded pipe. A flow separator divides the lower portion of the glass dome into inflow and outflow sides. Finally, an air bleed tube runs from the top center of the dome into the outflow tube.

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of 360-degree camera enclosure (image credit: N. Hanacek/NIST).

The cool water flowed into the dome cools both the construction and the camera and forces out the heated water that is absorbing the radiation from the fire. The flow separator causes mixing of the cool and heated water in the dome. Due to the pressure difference between the water at the top of the dome and in the outflow tube, the air bleed tube, which terminates just below the diaphragm in the outflow tube, ensures that air bubbles in the water supply line or that form due to micro-boiling at the inner surface of the glass do not collect at the top of the dome.

Because the construction is water cooled, most of the parts can be fabricated from mild steel. Only the clamping ring and posts are not effectively cooled by the water and must be fabricated using materials capable of withstanding the high temperatures in a fire. Experience has shown that it is important to reduce thermally-induced stress gradients in the construction as much as possible; in particular in the glass dome. The design in Fig. 4 is conceived to minimize ‘thermal shadowing’ on the glass which would cause stress gradients.

Placing the camera in water has two notable drawbacks. First, the camera’s audio fidelity is significantly reduced, and second, the water changes the index of refraction of visible light which affects the stitching of the images from the camera. The audio limitation can be overcome in some applications using external microphones; see Section 4. With regard to the stitching, monoscopic 360-degree cameras capture video from two cameras with hemispherical lens placed back-to-back. The video images are stitched together to form a flat spherical image that can be viewed like a projection on the inside of a globe. Because the water refracts (bends) the visible light, a portion of the field of view is corrupted along the seam between the two hemispherical images. This problem could be eliminated using a camera with additional overlapping lens and more sophisticated stitching techniques. However, the author found that the lost field of view along the seam (on the order of a few degrees of angle) did not warrant the effort to correct this. It is noted that scuba divers using 360-degree cameras also face this problem and it is possible that solutions will be commercially available in the future.

3. Fabrication examples

This section provides examples of the fabrication of the above-described concept design. The detailing and dimensioning of the system can vary based on the fire scenario. The examples provided are designed for use in large compartment fires or wildland fires.

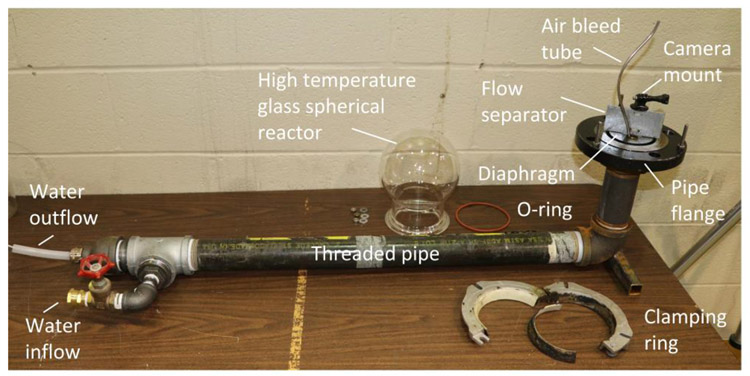

Fig. 5 shows the first functional prototype of what has been named the Burn Observation Bubble, or BOB for short. Except for the diaphragm, flow separator, and air bleed tube, all of the components are off-the-shelf items. A spherical reaction vessel made of borosilicate glass that allows the 360-degree camera to fit through the opening and provides a layer of water in all directions between the camera and the glass is first selected. Fused silica glass resists higher temperatures than borosilicate glass and can also be used but is significantly more expensive. The opening diameter dictates the clamping ring size as well as the pipe flange diameter. In this prototype a commercial clamping ring for reaction vessels is used to secure the spherical reactor to the pipe flange. The pipe diameter for the horizontal and vertical portions of the setup is governed by the magnitude of the thermal energy that will be transferred to the water, the resulting required volumetric flow rate to transport that heated water out of the setup and replace it with cool water before exceeding the specified temperature limit of the camera, and the maximum pressure that the waterproof camera can sustain. By using standard threaded pipe, the height of the camera and position in a room can be easily varied. The steel diaphragm is drilled through with two 12 mm diameter holes and welded to a pipe reducer that connects the pipe flange to the vertical threaded pipe (refer to Fig. 4). The hot water outflow hole is threaded to allow attachment of a compression fitting for high-density polyethylene tubing that runs inside the threaded pipe and out the rear of the setup. The flow separator is a thin piece of galvanized sheet steel attached to the camera mount post. Finally, the air bleed tube is constructed from stainless steel tube attached to the flow separator.

Fig. 5.

Photograph of first prototype of a Burn Observation Bubble.

For the design of the prototype in Fig. 5 it is assumed that a spherical reactor with a radius r of 0.0762 m is exposed to a constant heat flux q of 200 kW/m2 for an indefinite period of time (i.e., steady state conditions are achieved), that all heat transfer to the water takes place at the spherical reactor (i.e., heat transfer to the pipe is neglected), and that an infinite supply of 23 °C cooling water is available. The allowable residence time tres of the water in the spherical reactor to not exceed a temperature rise (ΔT) of 20 °C (i.e., a camera temperature of 43 °C) can be calculated from the heat capacity as:

| (1) |

where, for water, the density ρ is 1000 kg/m3 and the specific heat cp is 4200 J/kg–°C. The required volumetric flow rate of water through the sphere of volume V is then:

| (2) |

For this prototype, this yields an allowable residence time of 10.7 s for the water in the spherical reactor and a required volumetric flow rate of the water of 17.4 × 10−5 m3/s (10.4 1/min). While Eqns. (1) and (2) are often sufficient for design, more detailed heat transfer calculations were performed by Yang [19]. Yang’s dimensionless solutions based on the energy balance of a closed, recirculating system with a heated enclosure and a cooling reservoir incorporate time-dependent temperature change of the reservoir and enclosure, as well as the volume ratio of the two bodies. While Yang’s solutions simplify to Eqns. (1) and (2) under the assumptions stated above, in some applications the expanded solutions may be useful for design.

The required volumetric flow rate must be supplied with a pressure at the spherical reactor that does not exceed the pressure rating of the camera. Pressure to the water inflow in Fig. 5 will vary based on factors including on the water supply pressure, as well as the hose diameter and hose length between the supply and the setup. Consequently, determining this pressure for a given application using an in-line pressure gauge is recommended. The 50 mm diameter threaded pipe used for the prototype in Fig. 5 was selected because it provides a stable support for the spherical reactor and has sufficient inside diameter for the water outflow tube and compression fittings inside the pipe without restricting the water flow for the design volumetric flow rate.

In a setting where enough clean water is available, the cooling water can be supplied by a garden hose connected to the water supply and the water outflow can be discharged to a drainage. In humid environments, it is desirable to be able to adjust the inflow water temperature to avoid condensation from forming on the outside of the glass dome prior to fire growth.

Fig. 6 shows details of a subsequent prototype for deployment in wildland fires. In this application, a recirculated water supply was required so the setup is constructed out of stainless steel to avoid discoloration of the water due to oxidation. Additionally, the clamping ring (Fig. 6b) is custom made out of Inconel to sustain higher temperatures and the threaded posts and nuts are made of high-temperature A286 stainless steel (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Photographs of a Burn Observation Bubble for field deployment in wildland fires (a) top of flange without glass dome, (b) glass dome with clamping ring, (c) assembly at pipe flange.

4. Application examples

The following application examples are selected to illustrate significant evolutions of the system and learnings from deployments that may be useful to the reader. The 360-degree videos from these experiments and additional case studies are available online at https://www.nist.gov/el/fire-research-division-73300/national-fire-research-laboratory-73306/360-degree-video-fire.

4.1. Furnished compartment fire

An early deployment of the camera system was in a compartment fire inside of a replica of a museum collection storage room (Fig. 7a). The experiment was part of a training workshop with the Smithsonian Institution's Preparedness and Response in Collections Emergencies (PRICE) team held at the National Fire Research Laboratory (NFRL). The fire was ignited using an ‘electric match’ placed in a trashcan filled with shredded paper and plastic bottles and spread to involve a cardboard box filled with packing peanuts and neighboring materials (Fig. 7b). The fire was extinguished manually prior to compartment flashover using an overhead sprinkler when the upper layer gas temperature in the compartment reached approximately 750 °C. The peak heat release rate, measured using oxygen consumption calorimetry, was 2350 kW.

Fig. 7.

Furnished compartment fire experiment of a replica of a museum collection storage room: (a) compartment prior to ignition, (b) fire approximately 4 min after ignition.

The 360-degree camera was placed near the center of the room approximately 60 cm up from the floor. The height and location were selected to provide a good field of view but also so that the glass dome would stay below the calculated smoke layer. This reduced the chance that the dome would become obstructed by soot and smoke from the fire. In the approximately half dozen deployments of the BOB to date, in most cases soot obstruction has been minimal due to judicious placement of the camera or the use of low soot yield fuels. However, in applications where the dome becomes engulfed in smoke, soot deposition on the glass will severely limit visibility, making this setup unsuitable for many compartment fire environments.

Using the 360-degree camera setup in this application had three notable advantages over traditional video cameras. First, a single camera placed near the center of the compartment allowed viewing of multiple aspects of the experiment, e.g., fire ignition and growth, the condition of the dummy artifacts (no actual museum objects were used) located throughout the room, and smoke behavior, that would have otherwise required multiple, thermally-hardened, video cameras to capture. Second, the video can be viewed using a virtual reality head-mounted display, which is engaging for communication and training; a key requirement of the stakeholders from the Smithsonian Institution. Third, it is possible to overlay the resulting 360-degree video with compartment temperatures measured during the experiment using WebVR virtual reality software tools. Interactive, data-augmented 360-degree video provides new possibilities to communicate results from large fire experiments. A disadvantage of this approach was that, at present, commercially-available waterproof 360-degree video cameras do not permit wired1 live streaming of video. This meant that the video was recorded to the local memory on the camera and viewed after the experiment was complete.

During this deployment and a previous one, it was observed that the posts securing the clamping ring on the first prototype (Fig. 5) underwent excessive thermal expansion which relaxed the seal between the glass dome and the pipe flange allowing water to leak. Subsequently, the clamping ring and posts were redesigned from more temperature resistant materials and the post lengths were reduced to minimize thermal elongation (refer to Fig. 6).

In these experiments external audio was first added. Although audio can be recorded using the camera’s built-in microphones, sounds outside the glass dome are strongly attenuated by the water. For fires in open areas, audio can be obtained by placing directional microphones, e.g., cardioid ‘shotgun’ microphones, at a sufficient distance from the fire to avoid thermal damage. By placing two shotgun microphones in an XY-pattern that intersects at the camera (Fig. 8) one obtains (reversed) stereo sound at the position of the camera. The separately recorded audio can be overlaid on the video during post-processing. It should be noted that this audio will not track the rotation of the video during viewing, i.e., if you look 180° from the initial video orientation the sound will be reversed, however, if additional microphones are used, spatial audio that tracks the 360-degree field of view can be created using audio post-processing software. High-quality audio in a fire provides a more immersive viewing experience.

Fig. 8.

Example of directional microphones in an XY-pattern to record audio for fires in an open area.

For enclosed areas like compartment fires, thermally-protected omnidirectional capsule microphones placed at multiple locations can be used to record audio. An example for the museum collection fire is shown in Fig. 9a. While there is limited directionality to the audio, i.e., sounds close to the mic will sound louder, because the sounds in the room reflect off walls, the audio still feels natural when overlaid on the 360-degree video. To protect the microphones from thermal damage, they were placed low on the walls and covered with a noncombustible aramid fabric and an acoustically-transparent silver scrim to slow convective heat transfer and reflect radiant energy generated by the fire (Fig. 9b). While this worked for this application, temperatures measured at the microphones over 100 °C immediately prior to fire suppression suggest that they would have been destroyed had the fire been allowed to progress to flashover of the compartment. The sheet metal ‘roof’ above the microphone in Fig. 9b prevented water from the sprinklers from running down the wall into the microphone. The same capsule microphones covered with aramid fabric and an acoustically-transparent silver scrim were used to record audio successfully in wildland fires, however, in this application the microphones were buried underground (Fig. 9c).

Fig. 9.

Example of capsule microphones to record audio for fires: (a) one mounting location relative to camera in a compartment, (b) detail of thermal protection, (c) capsule microphone buried underground for use in wildland fire; the thermal protection is upside down next to microphone and not in its final position.

4.2. Prescribed forest management fire

360-degree video is particularly well-suited to fires in large areas where the fire moves over time. Forest fires are a good example of such an application. The camera system was deployed in a series of prescribed forest management fires in the Pinelands National Reserve of New Jersey, USA to investigate the performance of the camera system in this application and to provide video footage to the U.S. Forest Service and the researchers conducting the burns.

Because limited water was available in the forest, a recirculated water-cooling system was constructed that consisted of a plastic water tank and battery powered water pump that could run for 60 min and be buried underground (Fig. 10a). The required mass of water (mH2O) to maintain an allowable temperature rise (ΔT) of 20 °C for the camera was estimated assuming that all heat transfer from the fire to the water took place at the glass dome according to Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where the total heat flux q at the height of the dome as the fully-developed fire moved past the camera was assumed to be 100 kW/m2, the surface area of the glass A was 0.08 m2, the exposure time texp at peak heat flux was assumed to be 10 min, and the specific heat of water cp is 4200 J/kg–°C. This yields a required water mass of 57 kg (57 liters). More detailed heat transfer analysis that includes the time-dependent increase in reservoir temperature using the equations by Yang [19] show a slightly shorter time of 7 min will result in the 20 °C threshold being exceeded under the assumed conditions. Heat transfer to the water through the threaded pipe was neglected because it was planned to wrap the pipe in thermal ceramic fiber blanket. Although the pipe was ultimately left unwrapped, the above assumptions proved to be suitable for the fires studied.

Fig. 10.

Prescribed forest management fire: (a) camera setup with portable water supply, (b) equirectangular snapshot from 360-degree video taken during a crown fire.

360-degree video of two surface fires and one crown fire were recoded. The viewer can watch the fires progress from when they are lines on the horizon, warp around and engulf the camera and then recede into the distance. The movement of the treetops caused by the fire-driven winds, fire spread along the forest floor, as well as ember formation and spotting fires can be viewed in a single video. This allows the viewer to appreciate the behavior of the fires more completely than multiple, single camera views, had in past experiments [8]. The video can be unwrapped to an equirectangular format that allows one to see the fire in all directions at one time (Fig. 10b) and then zoomed to focus on fire behavior at a specific location of interest.

4.3. Parallel privacy fence fire

The final example is that of a parallel privacy fence fire. Additional information about these experiments is available in [20]. The camera is placed in close proximity to the burning material; the fence separation is 30 cm (Fig. 11). This illustrates an example of the camera system in a well-ventilated confined space with significant thermal radiation. The same recirculating water system from the prescribed forest management fire discussed above was used. Because the thermal radiation to the threaded pipe was significant, and not considered in the water mass calculations, the water exceeded the allowable temperature rise of 20 °C within less than 5 min and by the end of the approximately 15 min burn duration the water was boiling. While the camera did not shut down and the video footage was recovered from the memory card following the experiment, the 360-dgree camera was permanently damaged due to water leakage into the camera.

Fig. 11.

Fire test of parallel privacy fence panels: (a) side view of setup prior to placement of second fence panel, (b) end view of setup during fire growth.

Fig. 12 shows a snapshot of the flame spread along the inside fence surfaces. Without the water filtering the radiation, a camera could not survive in this intense thermal environment. By placing a single 360-degree camera at the center of the test specimen, the fire spread along the inside of the fences can be viewed from a perspective that was previously inaccessible. This is achieved with limited impact on the air flow between the fences; which was important for the experiment. Soot deposition was not a problem until late in the fire decay due to the well-ventilated conditions.

Fig. 12.

Equirectangular snapshot from 360-video taken during parallel privacy fence panel fire.

5. Conclusions and future work

A relatively thin (e.g., 30 mm) layer of water can be used to significantly reduce infrared radiation from a fire while remaining transparent to visible light. This insight was used to build simple, inexpensive (less than 1000 USD) and robust enclosures for cameras placed in fires. The transparent enclosure to house commercial monoscopic 360-degree cameras presented in this paper allows users to record video from the middle of intense fires for indefinite durations.

The fact that the camera can be placed at the center of a fire, provides new perspectives for many applications in fire research. Moreover, by using a 360-degree camera, the viewer can better understand the spatial development of the fire or zoom in to focus on specific regions of interest that can vary over the duration of the fire.

In addition to the video provided by these cameras, which can be viewed in immersive environments like the example in Fig. 13, work is ongoing at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to augment the 360-degree video with measurements taken during fire experiments. This data augmented 360-degree video provides the viewer with spatial and temporal context for the measurements and will hopefully be a useful tool for technical communication in fire science in the future.

Fig. 13.

360-degree video taken from within a prescribed forest management fire viewed in a cave automatic virtual environment (image credit: L. Gerskovic/NIST).

Highlights:

A simple and inexpensive way to significantly improve the tenability of video cameras in severe fire environments is described.

Fabrication details required to replicate the system are provided.

Three application cases that illustrate 360-degree video footage acquired using the system for various fire scenarios are shown to illustrate its strengths and weaknesses.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Special thanks are given to Andrew Mundy, Matthew Bundy, Jeffrey Fagen and Christopher Smith for their support and expertise, as well as to Michael Gallagher, Rory Hadden, and Erik Johnsson for allowing the author to deploy the camera in their fire experiments.

Footnotes

Wireless live streaming of low-resolution video is possible for many cameras, however, it shortens battery life and wireless communication through water to a receiving device at the standoff distances typically required for large fires is prohibitive.

6. References

- [1].Çetin AE, Dimitropoulos K, Gouverneur B, Grammalidis N, Günay O, Habiboğlu YH, Töreyin BU, Verstockt S, Video fire detection - Review, Digit. Signal Process. A Rev. J (2013). doi: 10.1016/jdsp.2013.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Xiao H, Gollner MJ, Oran ES, From fire whirls to blue whirls and combustion with reduced pollution, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 113 (2016) 9457–9462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605860113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Raj VC, Prabhu SV, Measurement of geometric and radiative properties of heptane pool fires, Fire Saf. J (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.firesaf.2017.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fang J, Wang J, Tu R, Shang R, ming Zhang Y, jun Wang J, Optical thickness of emissivity for pool fire radiation, Int. J. Therm. Sci (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2017.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bisby L, Gales J, Maluk C, A contemporary review of large-scale non-standard structural fire testing, Fire Sci. Rev 2 (2013) 1–27. doi: 10.1186/2193-0414-2-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hidalgo JP, Goode T, Gupta V, Cowlard A, Abecassis-Empis C, Maclean J, Bartlett AI, Maluk C, Montalva JM, Osorio AF, Torero JL, The Malveira fire test: Full-scale demonstration of fire modes in open-plan compartments, Fire Saf. J (2019). doi: 10.1016/j.firesaf.2019.102827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Beji T, Verstockt S, Van de Walle R, Merci B, On the Use of Real-Time Video to Forecast Fire Growth in Enclosures, Fire Technol. 50 (2012) 1021–1040. doi: 10.1007/s10694-012-0262-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Thomas JC, Mueller EV, Santamaria S, Gallagher M, El Houssami M, Filkov A, Clark K, Skowronski N, Hadden RM, Mell W, Simeoni A, Investigation of firebrand generation from an experimental fire: Development of a reliable data collection methodology, Fire Saf. J (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.firesaf.2017.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Finney MA, Cohen JD, Forthofer JM, McAllister SS, Gollner MJ, Gorham DJ, Saito K, Akafuah NK, Adam BA, English JD, Role of buoyant flame dynamics in wildfire spread., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112 (2015) 9833–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504498112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Water cooled camera enclosure for industrial high temperature applications, (n.d.). http://www.tecnovideocctv.com/cooled_camera_enclosure.php (accessed August 28, 2019).

- [11].Videotec Products, (n.d.). https://www.videotec.com/cat/en/products/fixed-cameras-and-housings/stainless-steel-housings-and-cameras/nxw/ (accessed August 28, 2019).

- [12].Madrzykowski D, Kerber S, Fire Fighting Tactics Under Wind Driven Conditions: Laboratory Experiments, NIST; TN 1618, Gaithersburg, MD, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Su J, Lafrance P, Hoehler M, Bundy M, Fire Safety Challenges of Tall Wood Buildings – Phase 2: Task 2 & 3 – Cross Laminated Timber Compartment Fire Tests, Fire Protection Research Foundation, Quincy, MA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hoehler MS, Andres B, Bundy MF, Influence of Fire on the Lateral Resistance of Cold-Formed Steel Shear Walls – Phase 2: Oriented Strand Board, Strap Braced, and Gypsum-Sheet Steel Composite (NIST; Technical Note 2038), Gaithersburg, 2019. doi: 10.6028/NIST.TN.2038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Putorti A, Mensch A, Bryner N, Braga GCB, Thermal Performance of Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus Facepiece Lenses Exposed to Radiant Heat Flux (NIST; Technical Note 1785), Gaithersburg, MD, 2013. doi: 10.6028/NIST.TN.1785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hoehler MS, Bundy MF, Su J, Dataset from Fire Safety Challenges of Tall Wood Buildings – Phase 2: Task 3 - Cross Laminated Timber Compartment Fire Tests, (2018). doi: 10.18434/T4/1422512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chaplin M, Water absorption spectrum, (2019). http://www1.lsbu.ac.uk/water/water_vibrational_spectrum.html (accessed August 29, 2019).

- [18].Hoehler MS, Smith CM, Application of blue laser triangulation sensors for displacement measurement through fire, Meas. Sci. Technol 27 (2016). doi: 10.1088/0957-0233/27/11/115201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yang JC, On the Cooling of a 360° Video Camera to Observe Fire Dynamics In Situ - NIST; TN 2080, Gaithersburg, MD, 2019. doi: 10.6028/NIST.TN.2080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Butler K; Johnsson E, Understanding the Fire Hazards from Fences, Mulch, and Woodpiles, in: Proc. 6th Int. Fire Behav. Fuels Conf., International Association of Wildland Fire, Missoula, 2019. [Google Scholar]