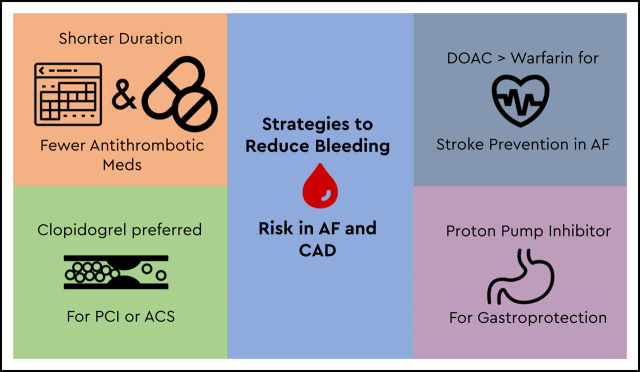

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Up to 10% of the >3 million Americans with atrial fibrillation will experience an acute coronary syndrome or undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. Therefore, concurrent indications for multiple antithrombotic agents is a common clinical scenario. Although each helps reduce thrombotic risk, their combined use significantly increases the risk of major bleeding events, which can be life threatening. In the past 5 years, a number of randomized clinical trials have explored different combinations of anticoagulation plus antiplatelet agents aimed at minimizing bleeding risk while preserving low thrombotic event rates. In general, shorter courses with fewer antithrombotic agents have been found to be effective, particularly when direct oral anticoagulants are combined with clopidogrel. Combined use of very low-dose rivaroxaban plus aspirin has also demonstrated benefit in atherosclerotic diseases, including coronary and peripheral artery disease. Use of proton pump inhibitor therapy while patients are taking multiple antithrombotic agents has the potential to further reduce upper gastrointestinal bleeding risk in select populations. Applying this evidence to patients with multiple thrombotic conditions will help to avoid costly and life-threatening adverse medication events.

Learning Objectives

Select appropriate patients with both atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease for dual therapy (oral anticoagulation and P2Y12 inhibitor therapy) to reduce bleeding risk

Select appropriate medication combinations for prevention of major adverse cardiovascular events for patients with atherosclerotic disorders

Apply multiple strategies to reduce bleeding risk for patients with multiple indications for anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy

Clinical case

The patient is a 65-year-old man who presented to the hospital with new chest discomfort at rest. He was diagnosed with a non–ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). He has a history of atrial fibrillation (AF), for which he takes warfarin to prevent stroke, but no prior history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or bleeding events. He is overweight but not obese (90 kg, body mass index of 27.0). He was initially treated with aspirin 325 mg once, then 81 mg daily. He was placed on an unfractionated heparin infusion before his PCI, when the infusion was discontinued. He was initiated on atorvastatin 80 mg daily and metoprolol tartrate 25 mg twice a day. His baseline laboratory studies included normal coagulation tests (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio), normal complete blood count, and normal renal function (serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL). Before he is discharged from the hospital, his physician wonders what the safest antithrombotic regimen to balance bleeding and thrombotic risk would be, given his known AF and recent ACS with PCI.

Introduction

Antithrombotic agents, consisting of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, are some of the most commonly prescribed medications. They are currently used by millions of Americans to prevent thrombotic complications in a wide variety of cardiovascular conditions.1 When combined, these medications increase the risk of significant bleeding complications. Recent studies have compared different combinations of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications for a variety of cardiovascular conditions. Applying the findings from these trials will help individual patients and their health care providers balance potential benefits and risks when selecting appropriate antithrombotic regimens.

Indications for antithrombotic therapies

Aspirin therapy has been used for decades to prevent and treat cardiovascular disease, including myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemic stroke. This usage is based, in part, on a series of studies published before 2005 demonstrating reductions in MI risk.2 Daily aspirin therapy was widely recommended in both clinical guidelines and the lay media, leading to broad application both with and without health care provider involvement. Aspirin is often combined with a P2Y12 receptor antagonist (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after PCI or ACS.3,4 Aspirin monotherapy or DAPT may also be used to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events for patients with peripheral artery disease.5 Oral anticoagulants, including warfarin and the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), are used for a wide range of thrombotic disorders, most commonly to prevent stroke and systemic embolism associated with AF and to prevent or treat venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Many patients have comorbid conditions that each have indications for different antithrombotic medications. In fact, up to half of patients with AF needing anticoagulation have comorbid coronary artery disease (CAD), nearly 10% of whom will undergo PCI and need antiplatelet therapy.6 However, with each additional antithrombotic agent that a patient is taking, their risk of major and life-threatening bleeding increases.7 Therefore, efforts to reduce bleeding risk for patients with comorbid prothrombotic conditions (eg, AF and PCI) are needed.

Combined anticoagulant–antiplatelet use by patients with multiple indications

Numerous trials have explored reducing the number of antithrombotic medications used by patients taking chronic oral anticoagulants, usually for AF, who then undergo PCI or experience an ACS that necessitates antiplatelet therapy. The first of these was the WOEST trial, an open-label trial comparing oral anticoagulation plus clopidogrel alone (double therapy) to oral anticoagulation plus DAPT (triple therapy).8 As might be expected, any bleeding was less common among patients in the double therapy group (19.4% vs 44.4%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.50). However, patients in the double therapy group also had fewer thrombotic events or deaths (11.1% vs 17.6%; HR 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38-0.94), including fewer MI, stroke, and stent thrombosis events.

As shown in Table 1, a number of subsequent trials compared variable numbers of antithrombotic medications, different anticoagulants (warfarin vs DOACs), and different dosages of anticoagulants (full dose vs reduced dose).9-12

Table 1.

Trials of combined antithrombotic therapy for AF and CAD

| Name | WOEST8 | PIONEER AF-PCI11 | RE-DUAL PCI9 | AUGUSTUS12 | ENTRUST-AF PCI13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 573 | 2124 | 2725 | 4614 | 1506 |

| Population | Patients taking OAC undergoing PCI | Patients with AF undergoing PCI | Patients with AF undergoing PCI | Patients with AF and recent ACS or PCI | Patients with AF and recent ACS or PCI |

| ACS | 155 (27.1%) | 1096 (51.6%) | 1744 (64.0%) | 2811 (60.9%) | 777 (51.6%) |

| Treatments |

|

|

|

|

|

| Notable exclusion criteria | Prior intracranial bleed, cardiogenic shock, recent peptic ulcer or major bleeding, or thrombocytopenia | Prior stroke, recent GI bleeding event, CrCl <30 mL/min, or anemia (Hg <10 g/dL) | Cardiac valve replacement (mechanical or bioprosthetic) or CrCl <30 mL/min | Anticoagulant use for indications other than AF, severe renal insufficiency, prior intracranial bleed, recent or planned coronary artery bypass graft surgery, or ongoing bleeding | Mechanical heart valve, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, and end-stage renal disease |

| Bleeding outcome: rate and definition |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bleeding outcome definition | Any bleeding | TIMI major + minor bleeding | ISTH major + CRNM bleeding | ISTH major + CRNM bleeding | ISTH major + CRNM bleeding |

CrCl, creatinine clearance; CRNM, clinically relevant nonmajor; Hg, hemoglobin; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; OAC, oral anticoagulant; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; TT, triple therapy; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

The largest trial comparing different oral anticoagulant dosages and number of antithrombotic medications is the AUGUSTUS trial.11 This trial used a 2 × 2 factorial design to compare treatment dosages of both warfarin and apixaban and to compare DAPT to clopidogrel alone in patients with AF who had undergone PCI or experienced an ACS. The findings suggest a marked reduction in major bleeding associated with the use of apixaban as compared with warfarin and with omission of aspirin therapy. Collectively, when the warfarin–clopidogrel–aspirin triple therapy combination was compared with the apixaban–clopidogrel double therapy combination, only 9 patients needed to be treated with the apixaban–clopidogrel regimen to avoid 1 major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding event. Of note, not all trials used full treatment dosages of anticoagulants, which limits the ability to compare the impact of different anticoagulant drugs and dosage combinations with the inclusion or omission of aspirin therapy on bleeding outcomes. Although some suggest that clinicians select the lowest possible anticoagulant dosage when combining with antiplatelet therapy, others favor use of an anticoagulant dosage that has been proven effective for stroke prevention in AF.

Equally important, the risk reduction in cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, and stent thrombosis associated with aspirin use is concentrated in the first 30 days but does not extend beyond that time point.13 In fact, there is a nearly equal increased risk of ischemic events and decreased risk of bleeding events in the first 30 days after PCI or ACS. But after those initial 30 days, the increased risk of bleeding associated with aspirin use persists, whereas the ischemic risk is equal with and without aspirin therapy.

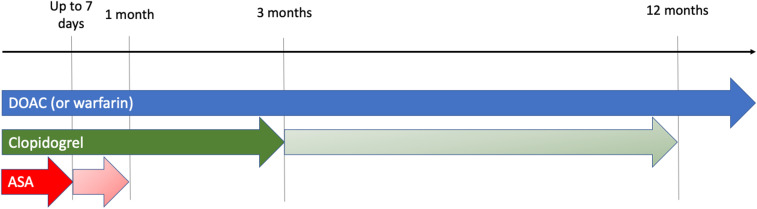

Independent of the need for ongoing anticoagulant therapy, recent studies have suggested that shorter courses of DAPT (sometimes ≤3 months) may be appropriate for many patients undergoing PCI.14,15 Therefore, many cardiovascular specialists, including interventional cardiologists, are recommending shorter courses of DAPT for patients after PCI or an ACS if they are taking concurrent anticoagulant medications (Figure 1). In fact, recent guidelines and expert consensus documents recommend shorter courses of triple therapy for most of these patients.16-18 This recommendation is supported by 2 recent meta-analyses showing lower rates of bleeding when dual therapy (an anticoagulant plus P2Y12 inhibitor) rather than triple therapy is used.19,20 This is particularly true for the combination of a DOAC plus P2Y12 inhibitor and is similar in both stable CAD and ACS. Fortunately, the meta-analyses have also demonstrated no significant increased risk in all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, MI, stent thrombosis, major adverse cardiac events, or stroke.

Figure 1.

Timeline of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease. For patients with high thrombotic risk (including ACS), ≥3 months (and ≤12 months) of clopidogrel and ≤1 month of aspirin (ASA) is recommended. Longer courses of clopidogrel use may be appropriate for patients with high ischemic risk or who experience an ACS. For PCI for stable angina, a shorter course of clopidogrel and ASA (≤7 days) may be more appropriate (indicated by dark shaded arrows).

In general, oral anticoagulant monotherapy is recommended for patients with AF who need anticoagulation for stroke prevention and have concomitant stable CAD (last ACS or PCI >12 months earlier). Although evidence in favor of this recommendation is less robust than evidence for therapy in the first 6 to 12 months after PCI, 2 recent trials demonstrated relative safety with regard to both bleeding outcomes and thromboembolic events (eg, MI, death).21,22 Some degree of caution is advised because 1 study was terminated prematurely for failure to enroll,22 and the other was conducted in a purely Japanese population.21 Nevertheless, concurrent use of oral anticoagulation with aspirin for patients with AF and stable CAD remains common and will probably require further efforts to promote deprescribing, including rigorous evaluation of these deprescribing efforts.23

Although the data on anticoagulation alone versus anticoagulation plus single antiplatelet therapy are limited for patients with stable CAD, there is more robust evidence that aspirin may have net clinical harm for primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease.2 This is particularly true for patients taking chronic anticoagulant therapy but without a clear indication for concurrent antiplatelet treatment.24 Efforts to reduce aspirin use in this population may lead to reductions in medication-related adverse events, including hospitalizations.25

Although data have rapidly emerged on the risks and benefits of double versus triple antithrombotic therapy for patients taking oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in AF, much less data is available for patients with VTE who need PCI. For most patients with VTE on oral anticoagulation, an approach similar to that of patients with AF can be taken. Namely, if a patient on chronic oral anticoagulation for VTE experiences an ACS or PCI, dual therapy with an oral anticoagulant (preferably DOAC) and P2Y12 inhibitor is generally recommended. However, for patients with acute VTE in the first 1 to 3 weeks of therapy, caution is advised if DAPT is combined with higher daily doses of either apixaban or rivaroxaban. For any patient with acute VTE early in their course of therapy, it may be advisable to delay PCI until after induction dosing for VTE is complete when possible (eg, PCI for stable angina). This also allows time to discuss the role of dual therapy (anticoagulation plus P2Y12 inhibitor) versus triple therapy with the interventional cardiologist. For patients whose recurrent risk for VTE is low, discontinuing anticoagulant therapy may be reasonable if a strong indication for antiplatelet therapy exists. Though less effective at reducing VTE recurrence risk, aspirin monotherapy is associated with a 32% relative risk reduction.26

Combined anticoagulant–antiplatelet use by patients with atherosclerotic disease

Although the most common combined anticoagulant–antiplatelet use involves patients with multiple indications (eg, AF and CAD), trial data support the use of select combined regimens for patients with various atherosclerotic disorders (Table 2). In the ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51 study, patients with ACS were randomly assigned to receive either rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily, rivaroxaban 5 mg twice daily, or placebo in addition to DAPT for a mean of 13 months.27 Although the primary composite efficacy end point of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke was reduced for both rivaroxaban dosages as compared with placebo, there was also a significantly increased risk of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage. A similar study, APPRAISE-2, randomly assigned patients with ACS to receive apixaban 5 mg twice a day or placebo in addition to DAPT.28 This study was stopped prematurely because of an excess of major bleeding events among patients taking apixaban plus DAPT (2.4 vs 0.9 per 100 patient-years, HR 2.59; 95% CI, 1.50-4.46).

Table 2.

Trials of combined antithrombotic therapy for atherosclerotic disease

| Name | APPRAISE-2 | ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51 | COMPASS | VOYAGER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 7392 | 15 526 | 27 395 | 6564 |

| Population | Patients with recent ACS and additional risk factors for recurrent ischemic events | Patients with recent ACS | Patients with stable CAD or PAD | Patients with PAD undergoing revascularization |

| Treatments |

|

|

|

|

| Notable exclusion criteria | Severe hypertension, CrCl < 20 mL/min, active bleeding, recent ischemic stroke, NYHA class IV heart failure, prior intracranial bleeding, anemia (Hg <9 g/dL), thrombocytopenia, ongoing use of anticoagulation or aspirin >325 mg daily | Thrombocytopenia, anemia (Hg <10 g/dL), CrCl <30 mL/min | High risk of bleeding, recent stroke, severe heart failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate <15 mL/min, use of dual antiplatelet therapy, or anticoagulation use | Unstable clinical condition, high risk for bleeding, or long-term use of clopidogrel (beyond 6 mo) |

| Efficacy outcome |

|

|

|

|

| Primary safety outcome |

|

|

|

|

| Intracranial bleeding |

|

|

|

|

CrCl, creatinine clearance; Hg, hemoglobin; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; PAD, peripheral artery disease; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; TT, triple therapy.

In the subsequent COMPASS trial, patients with stable CAD or peripheral artery disease (PAD; including carotid artery disease) were randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily plus aspirin 100 mg daily, rivaroxaban 5 mg twice daily without aspirin, or aspirin 100 mg daily.29 The composite primary outcome of cardiovascular death, stroke, or MI occurred less often among patients randomly assigned to rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily plus aspirin than among patients taking aspirin alone. Although major bleeding was higher in the rivaroxaban–aspirin combination group, there was no increased in intracranial or fatal bleeding as compared with aspirin monotherapy, a key distinction from the ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51 study results.27 Most recently, the VOYAGER study randomly assigned patients with PAD who had undergone revascularization to receive rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily or placebo in addition to aspirin.30 Patients receiving both rivaroxaban and aspirin experienced fewer thrombotic events (composite of acute limb ischemia, major amputation for vascular causes, MI, ischemic stroke, or cardiovascular death) than patients receiving aspirin monotherapy. Major bleeding was more common in the rivaroxaban plus aspirin group than the aspirin monotherapy group according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) definition but not the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) definition. There was no difference in intracranial or fatal bleeding between the two groups (0.52% vs 0.58%; HR 0.91; 95% CI, 0.47-1.76).

Taken together, these 4 trials outline a few key findings for combined anticoagulant–antiplatelet use in atherosclerotic disease. First, bleeding is a significant concern when anticoagulants are combined with DAPT, as has been shown in the AF plus CAD studies outlined earlier. Second, although major bleeding often increases with combined anticoagulant–antiplatelet combinations, fatal and intracranial hemorrhage risk appear to be increased when a third antiplatelet medication (eg, P2Y12 inhibitor) is included. Third, the anticoagulant drug and dosage selection is critical. Full-dose anticoagulation in the APPRAISE-2 study (apixaban 5 mg twice daily) was associated with higher rates of major bleeding.28 However, very low dosages of rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) were overall safe and efficacious in the COMPASS and VOYAGER studies.29,30

Other strategies to reduce bleeding risk

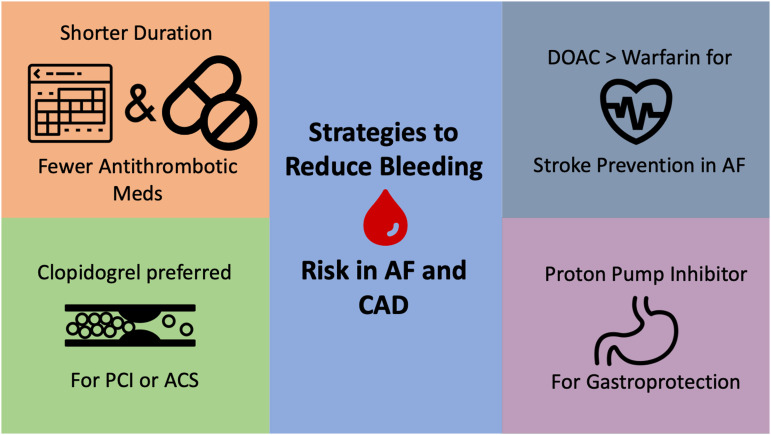

Although reducing the total number of antithrombotic medications is highly effective at reducing bleeding risk, this is not always feasible and does not completely eliminate bleeding risk for patients. Other strategies may be recommended (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Strategies to reduce bleeding risk for patients with AF and CAD.

First, the use of clopidogrel is recommended over other P2Y12 inhibitors (eg, prasugrel, ticagrelor) for patients taking concurrent oral anticoagulants. In fact, most patients in the randomized trials detailed earlier used clopidogrel rather than prasugrel or ticagrelor. This recommendation is also supported by a class IIa recommendation from the 2019 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guideline on AF management and the 2018 European Consensus guidelines.17,31

Second, use of a DOAC is preferred to warfarin when combined with either single antiplatelet or DAPT therapy. Although only the AUGUSTUS trial was designed for a head-to-head comparison of warfarin and a DOAC independent of antiplatelet therapy, data from randomized trials in AF, VTE, and other indications have generally demonstrated safety with the entire class of DOAC medications, especially with regard to intracranial hemorrhage.32 This finding has been reinforced in a number of guidelines and expert consensus documents favoring DOAC use over warfarin, both in general and when combined with antiplatelet therapy.16,31,33

Third, patients who need combined use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet medications are at increased risk for upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can be highly effective at reducing this risk, but they are often underused.34-37 Data supporting reductions in hospitalizations for upper GI bleed exist for patients taking anticoagulants and concurrent aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.34,35 Although the primary bleeding outcome was not significantly reduced in the PPI arm of the COMPASS trial (HR 0.88; 95% CI, 0.67-1.15), there was a reduction in overt GI bleeding events (HR 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.94).36 The low dosage of anticoagulant used in this study may have affected the overall bleeding rates. However, concerns remain regarding long-term PPI use and risk of cardiovascular disease, renal insufficiency, Clostridium difficile infection, and fracture risk.38 Guidelines from both North America and Europe recommend PPI use for patients taking combined anticoagulant–anticoagulant therapy given that the reduction in elevated GI bleeding risk probably outweighs any potential drug-related adverse event risk.17,39 It is also important to address PPI deprescribing once the bleeding risk has been mitigated (eg, transition to anticoagulation monotherapy).

Return to the case

The patient’s hospitalist and interventional cardiologist discuss the risks and benefits of various combinations of antithrombotic agents. Overall, the patient is thought to be at low bleeding risk given that he has not had a prior history of bleeding, has normal renal function, and has normal blood counts. Nonetheless, to minimize bleeding risk, they elect to change his warfarin to apixaban 5 mg twice daily, following data from the AUGUSTUS trial. Because he experiences an ACS, the interventional cardiologist feels more comfortable continuing aspirin 81 mg daily for 30 days, but then agrees to stop aspirin and continue dual therapy (apixaban and clopidogrel) for the remainder of the 12 months. This duration is selected because the patient experienced an ACS event. The hospitalists recommended use of a PPI to help minimize bleeding risk while the patient was taking multiple antithrombotic medications. The interventional cardiologist agrees to follow the patient for ≥12 months so that he can reassess the need for ongoing antiplatelet therapy in the future and address PPI deprescribing when a transition to apixaban monotherapy is initiated.

Conclusion

Combined use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications is common for patients with comorbid cardiovascular conditions, including CAD, AF, and VTE. Recent trial evidence has outlined the safety and efficacy of reducing the number of antithrombotic agents, favoring dual therapy (oral anticoagulant plus a single antiplatelet agent) in many clinical contexts. Additional strategies, including the use of clopidogrel over other P2Y12 inhibitors, preferential use of DOACs over warfarin, and use of PPI therapy, to reduce bleeding risk, should be explored for many patients who need multiple antithrombotic agents.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah R, Khan B, Latham SB, Khan SA, Rao SV. A meta-analysis of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in the context of contemporary preventive strategies. Am J Med. 2019;132(11):1295-1304 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):1150-1151]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):1082-1115.27036918 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. ; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(24):e44-e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):1521]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):e71-e126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michniewicz E, Mlodawska E, Lopatowska P, Tomaszuk-Kazberuk A, Malyszko J. Patients with atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease: double trouble. Adv Med Sci. 2018;63(1):30-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen ML, Sørensen R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(16):1433-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, et al. ; WOEST study investigators. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1107-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, et al. ; RE-DUAL PCI Steering Committee and Investigators. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1513-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connolly SJ, Milling TJ Jr, Eikelboom JW, et al. ; ANNEXA-4 Investigators. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopes RD, Heizer G, Aronson R, et al. ; AUGUSTUS Investigators. Antithrombotic therapy after acute coronary syndrome or PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(16):1509-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Eckardt L, et al. Edoxaban-based versus vitamin K antagonist–based antithrombotic regimen after successful coronary stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation (ENTRUST-AF PCI): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1335-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander JH, Wojdyla D, Vora AN, et al. Risk/benefit tradeoff of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation early and late after an acute coronary syndrome or percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from AUGUSTUS. Circulation. 2020;141(20):1618-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik AH, Yandrapalli S, Shetty SS, et al. Meta-analysis of dual antiplatelet therapy versus monotherapy with P2Y12 inhibitors in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2020;127:25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wernly B, Rezar R, Gurbel P, Jung C. Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) followed by P2Y12 monotherapy versus traditional DAPT in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: meta-analysis and viewpoint. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49(1):173-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capodanno D, Huber K, Mehran R, et al. Management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients undergoing PCI: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):83-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lip GYH, Collet JP, Haude M, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 Joint European consensus document on the management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous cardiovascular interventions: a joint consensus document of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), and European Association of Acute Cardiac Care (ACCA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), and Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA). Europace. 2019;21(2):192-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(2):87-165.30165437 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopes RD, Hong H, Harskamp RE, et al. Safety and efficacy of antithrombotic strategies in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(8):747-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan SU, Osman M, Khan MU, et al. Dual versus triple therapy for atrial fibrillation after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):474-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasuda S, Kaikita K, Akao M, et al. ; AFIRE Investigators. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1103-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumura-Nakano Y, Shizuta S, Komasa A, et al. ; OAC-ALONE Study Investigators. Open-label randomized trial comparing oral anticoagulation with and without single antiplatelet therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease beyond 1 year after coronary stent implantation. Circulation. 2019;139(5):604-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopin D, Jones WS, Klein A, Barnes GD. Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in stable coronary artery disease: a multicenter survey. Thromb Res. 2019;180(April):25-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaefer JK, Li Y, Gu X, et al. Association of adding aspirin to warfarin therapy without an apparent indication with bleeding and other adverse events. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):533-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaefer JK, Errickson J, Gu X, et al. Reduced bleeding after an intervention to limit excess aspirin use among patients on chronic warfarin. RPTH. 2020;4(suppl 1):PB2041. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simes J, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. ; INSPIRE Study Investigators (International Collaboration of Aspirin Trials for Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism). Aspirin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism: the INSPIRE collaboration. Circulation. 2014;130(13):1062-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, et al. ; ATLAS ACS 2–TIMI 51 Investigators. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(1):9-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander JH, Lopes RD, James S, et al. ; APPRAISE-2 Investigators. Apixaban with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):699-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J, et al. ; COMPASS Investigators. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1319-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonaca MP, Bauersachs RM, Anand SS, et al. Rivaroxaban in peripheral artery disease after revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1994-2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019;140(2):e125-e151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Lavie CJ, et al. Risk of major bleeding in different indications for new oral anticoagulants: insights from a meta-analysis of approved dosages from 50 randomized trials. Int J Cardiol. 2015;179:279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report [published correction appears in Chest. 2016;150(4):988]. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with reduced risk of warfarin-related serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1105-1112 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Association of oral anticoagulants and proton pump inhibitor cotherapy with hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2221-2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. ; COMPASS Investigators. Pantoprazole to prevent gastroduodenal events in patients receiving rivaroxaban and/or aspirin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(2):403-412.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurlander JE, Gu X, Scheiman JM, et al. Missed opportunities to prevent upper GI hemorrhage: the experience of the Michigan Anticoagulation Quality Improvement Initiative. Vasc Med. 2019;24(2):153-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoenfeld AJ, Grady D. Adverse effects associated with proton pump inhibitors. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):172-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation. 2008;118(18):1894-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]