Abstract

Giant left atrial appendage aneurysms (LAAAs) are rare causes of recurrent cardioembolism and managed routinely by surgery. A first catheter closure of a giant LAAA is reported, when a recent cerebral infarct precluded immediate surgery. Planning included ostial measurement on multimodal imaging, echo navigation for septal puncture, rotational angiogram for profiling, overlay imaging for device placement, and cerebral embolic protection from thrombus debris.

Keywords: Cardioembolism, device closure, left atrial appendage aneurysm, recurrent embolic strokes, rotational angiogram

INTRODUCTION

Giant left atrial appendage aneurysms (LAAAs) are caused by dysplasia of pectinate muscles in the appendage.[1] Criteria for diagnosis include origin from a normal left atrium, well-defined neck, and intrapericardial position and distortion of the left ventricular free wall by the aneurysm.[2] Their progressive enlargement in the second to fourth decades leads to atrial fibrillation, thromboembolism, ventricular distortion, pulmonary vein compression, mitral regurgitation, or fatal rupture.[3] Fetal or infantile detection is rare.[4,5] Differential diagnosis include left atrial dissection, cysts, tumors, and herniation through partially absent pericardium and pericardial cysts.[1] Surgery on or off bypass may be risky or morbid.[6,7] A transcatheter closure of this condition is reported for the first time, with emphasis on planning and follow-up.

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old patient presented with seizures and abnormal behavior due to a left frontal lobe infarction. Agitated saline study excluded patent foramen ovale. Despite aspirin and clopidogrel, she developed another right middle cerebral artery infarction after 6 months warranting a cardiac re-evaluation. Echocardiogram identified a “minimal localized left-sided pericardial effusion” on both admissions but “was not tapped.” Investigations for tuberculosis, vasculitis, and other inflammatory diseases were negative.

On presentation, clinical cardiovascular and neurological examinations were unproductive as was the electrocardiogram. Routine and transesophageal echocardiogram showed a large LAAA communicating to the left atrium through a 20-mm ostium showing to-and-fro flows [Figure 1]. Computed tomography confirmed a giant LAAA measuring 10.8 cm that was larger than the combined size of the left atrium and ventricle with a 20-mm communicating orifice [Figure 2]. Recent stroke precluded cardiopulmonary bypass and favored a transcatheter intervention after obtaining informed consent. Oral anticoagulation was stopped for 5 days under cover of enoxaparin.

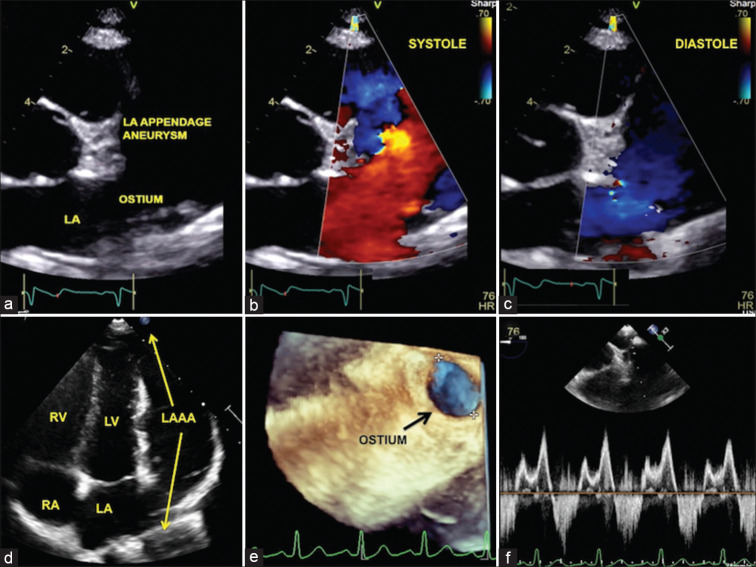

Figure 1.

To-and-fro blood flows in the left atrial appendage aneurysm. Echocardiogram in the parasternal short-axis view (a) showing the ostium of the left atrial appendage aneurysm with to-and-fro flows from the left atrium in systole (b) and diastole (c). Apical view (d) showing a comparison of the large fifth chamber to the four chambers of the heart. Transesophageal three-dimensional volume rendered image (e) assisted ostial measurement. Spectral Doppler (f) showing systolic entry of blood into the aneurysm and diastolic exit

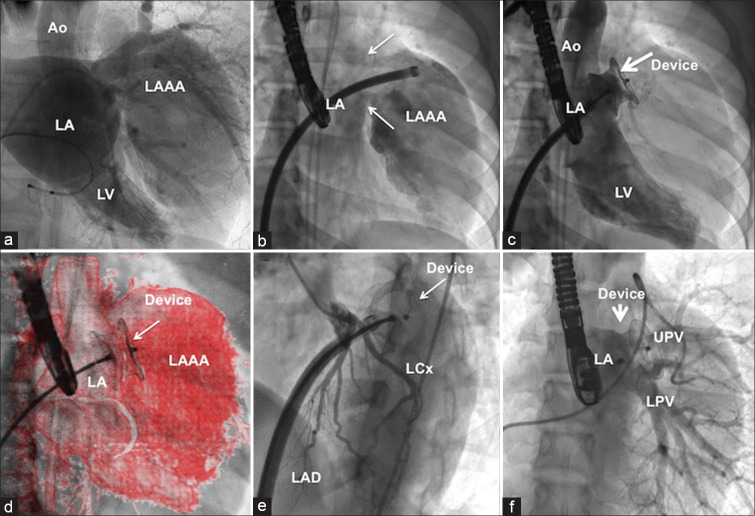

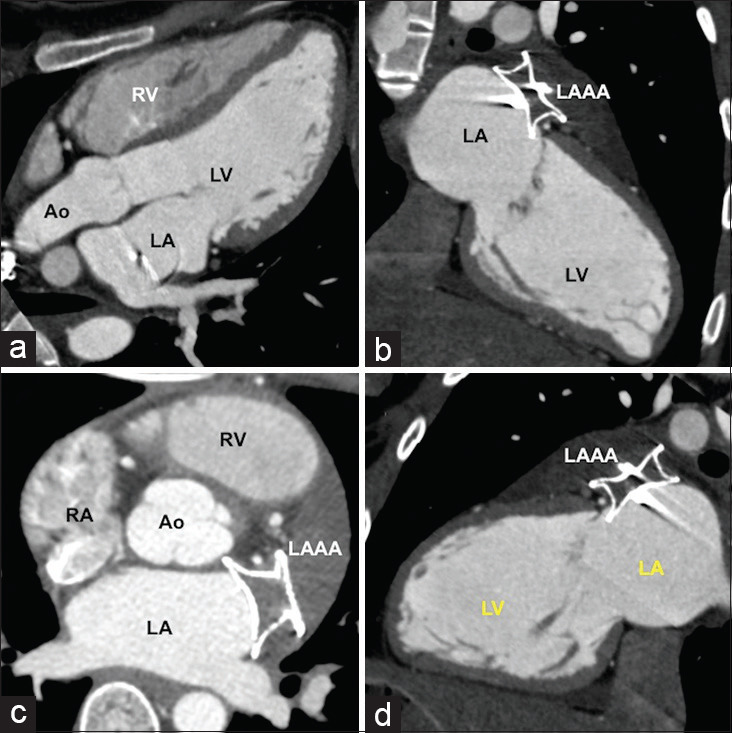

Figure 2.

Computed tomographic analysis. Multiplanar reformatted (a and b), axial (c), and color-coded volume-rendered (d) images of computed tomography-assisted ostial measurement and excluded large thrombus with the sac. RA: Right atrium, RAA: Right atrial appendage, LA: Left atrium, LAAA: Left atrial appendage aneurysm, LV: Left ventricle, Ao: Aorta, PA: Pulmonary artery, LPA: Left pulmonary artery, SVC: Superior vena cava

Two femoral arterial accesses facilitated placing two SpiderFX embolic protection filters (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to protect from thrombus debris in both carotid arteries. Echonavigation (Philips Medical System, Best, The Netherlands) guided a transseptal puncture in the posteroinferior part of the interatrial septum. Activated clotting time was maintained above 250 s. The working imaging plane to profile the ostium of the LAAA was determined by a rotational left atrial angiogram [Online Video]. A good separation of the LAAA and left atrium was seen in 26° right–anterior–oblique projections, which profiled the orifice. A hydrophilic angled Radifocus Glidewire (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) gently manipulated into the LAAA assisted passage of a 10F Mullins sheath (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) beyond the ostium. A 24-mm Amplatzer Postinfarct muscular VSD occluder (Abbott Medical, Plymouth, MN, USA) was deployed precisely across the ostium facilitated by overlay of the three-dimensional roadmap from the rotational angiogram dataset [Figure 3]. The closure was confirmed by angiography and transechocardiography. Patency of the left circumflex artery and left pulmonary veins was confirmed before release of the device.

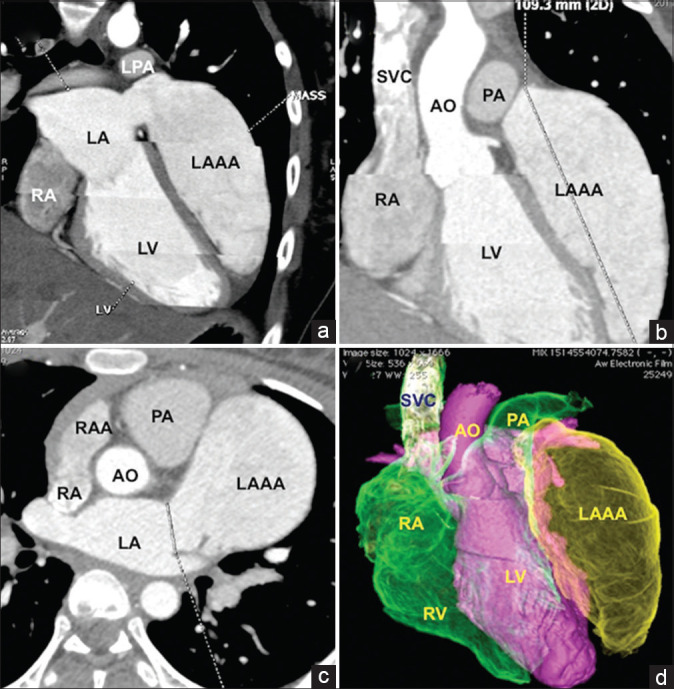

Figure 3.

Catheter closure of ostium of left atrial appendage aneurysm. Still-frame of rotational left atrial angiogram (a) identified right anterior oblique projection 26° degree as the best imaging plane [Online Video] to separate the left atrium and the aneurysm (b) that helped deployment of a 24-mm postmyocardial infarction muscular ventricular septal occluder device (c) using overlay imaging (d). Absence of left circumflex artery compression (e) and left upper pulmonary vein and lower pulmonary vein impingement (f) by the device was confirmed. LAD: Left anterior descending interventricular artery

Postprocedural fever for 1 week with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate possibly due to inflammation from massive thrombus in the aneurysm was managed with indomethacin. A persistent sinus tachycardia for 2 weeks was treated with beta-blockers. Immediate postprocedural computed tomography confirmed complete thrombosis of the LAAA [Figure 4]. Dual antiplatelet therapy was weaned after 1 year. A repeat imaging at a follow-up of 30 months showed complete shrinkage of the thrombosed sac [Figure 5].

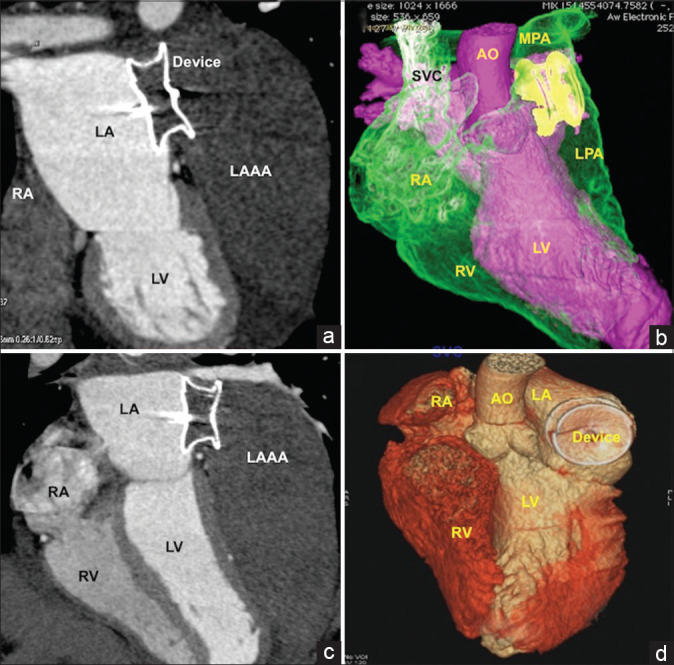

Figure 4.

Complete thrombosis of the aneurysmal sac. Immediate postprocedural computed tomography in multiplanar reformatted (a and c) and volume-rendered images (b and d) showing complete closure of the ostium of the aneurysm leading to thrombosis in the entire sac. The left atrial disc of the device was well opposed to left atrial walls to promote future endothelialization

Figure 5.

Three-year follow-up. Computed tomography after 3 years showed complete shrinkage of the aneurysmal sac and adequate endothelialization of the edges of the device in multiplanar reformatted (a and b), axial (c), and modified sagittal (d) views

DISCUSSION

Giant LAAA is seldom suspected in cryptogenic strokes due to its rarity.[1,3] Immediate surgery on cardiopulmonary bypass is forbidden if there are recent large brain infarcts.[6,7] Even though catheter closure is never reported, multimodal imaging of the ostium of the aneurysm suggested feasibility. Technological assistance included precise septal puncture guided by echo navigation, cerebral embolic protection from thrombus debris, profiling imaging plane that separates the LAAA from the atrium using rotational angiogram, and use of the roadmap during device deployment. This is the first planned catheter intervention in this rare condition, which presented a heart with an aneurysmal fifth chamber.[8] Even though a thrombus was not detected in the large aneurysm on transesophageal echocardiography, cerebral protection strategy was followed due to recent recurrence of stroke. Vertebral arteries were not covered due to nonavailability of appropriate protection strategies. Postmyocardial infarction ventricular septal rupture device was chosen due to its availability in large size to suit the 20-mm orifice.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Videos Available on: www.annalsofian.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Chowdhury UK, Seth S, Govindappa R, Jagia P, Malhotra P. Congenital left atrial appendage aneurysm: A case report and brief review of literature. Heart Lung Circ. 2009;18:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foale RA, Gibson TC, Guyer DE, Gillam L, King ME, Weyman AE. Congenital aneurysms of the left atrium: Recognition by cross-sectional echocardiography. Circulation. 1982;66:1065–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.5.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson D, Kalra N, Brody EA, Van Dyk H, Sorrell VL. Left atrial appendage aneurysm-A rare anomaly with an atypical presentation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2009;4:489–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2009.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aydin Sahin D, Vefa Yildirim S, Ozkan M. A rare giant congenital left atrial appendage aneurysm in a 1-day-old newborn. Echocardiography. 2018;35:757–9. doi: 10.1111/echo.13883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho MJ, Park JA, Lee HD, Choo KS, Sung SC. Congenital left atrial appendage aneurysm diagnosed by fetal echocardiography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38:94–6. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadowaki MH, Berger S, Shermeta DW, Arcilla RA, Karp RB. Congenital left atrial aneurysm in an infant. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:306–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaliciñski ZM, Jr, Orłowska H, Werner B. Images in congenital heart disease. Symptomatic left atrial aneurysm in a neonate. Cardiol Young. 2001;11:654–5. doi: 10.1017/s1047951101001032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nezafati MH, Nazari Hayanou H, Kahrom M, Khooei A, Nezafati P. Five chambered heart: Case of a huge left atrial appendage aneurysm. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2018;34:43–45. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.