Abstract

Canine malignant mammary gland tumors present with a poor prognosis due to metastasis to other organs, such as lung and lymph node metastases. Unlike in human studies where obesity has been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, this has not been well studied in veterinary science. In our preliminary study, we discovered that leptin downregulated cathepsin A, which is responsible for lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2a (LAMP2a) degradation. LAMP2a is a rate-limiting factor in chaperone-mediated autophagy and is highly active in malignant cancers. Therefore, in this study, alterations in metastatic capacity through cathepsin A by leptin, which are secreted at high levels in the blood of obese patients, were investigated. We used a canine inflammatory mammary gland adenocarcinoma (CHMp) cell line cultured with RPMI-1640 and 10% fetal bovine serum. The samples were then subjected to real-time polymerase chain reaction, Western blot, immunocytochemistry, and lysosome isolation to investigate and visualize the metastasis and chaperone-mediated autophagy-related proteins. Results showed that leptin downregulated cathepsin A expression at both transcript and protein levels, whereas LAMP2a, the rate-limiting factor of chaperone-mediated autophagy, was upregulated by inhibition of LAMP2a degradation. Furthermore, leptin promoted LAMP2a multimerization through the lysosomal mTORC2 (mTOR complex 2)/PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase 1 (PHLPP1)/AKT1 (Serine/threonine-protein kinase 1) pathway. These findings suggest that targeting leptin receptors can alleviate mammary gland cancer cell metastasis in dogs.

Keywords: leptin, canine adenocarcinoma, CTSA, metastasis, obesity

1. Introduction

Leptin is a peptide hormone produced and secreted mainly by adipose cells, playing a crucial role in reproduction [1], appetite [2], and cancer environment [3]. Previous studies described leptin as a tumor metastasis-promoting factor that induces inflammation [4] and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), mostly in malignant breast [5,6] and lung cancers [7,8]. Thus, many studies have been conducted to find novel antagonists against the leptin receptor (OBR) [9]. Of these, Allo-aca, a leptin antagonist binding selectively to the C-terminus of OBR without any agonistic effects, has been shown to be effective against triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) by increasing survival rates [10]. As the blood leptin concentration increases proportionally to the degree of obesity and aging in both humans and dogs [11,12,13,14,15], the regulation of leptin activity is crucial for managing and inhibiting cancer. Given the potential similarity between them, canine mammary gland tumors (CMTs) are considered as a model for investigating human breast cancer [16]. Similar to women, mammary gland tumors are the most common tumor in domestic intact bitches, and approximately half of them are diagnosed as malignant [11]. Canine inflammatory mammary carcinoma (cIMC) is a fast-growing, malignant form that shows poor prognosis (mean survival time of 25 days) because of its high incidence of metastasis to regional lymph nodes [17], which has risk factors that are similar to those of human breast cancers (e.g., age, progesterone, obesity) [18,19].

It has been suggested that leptin upregulates autophagy and promotes lysosomal degradation of long-lived proteins in adipose cells [20] and MCF-7 cells [4]. Lysosomal activity is closely related to autophagy, especially chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), a selective form of autophagy targeting substrate proteins bearing KFERQ-motifs (e.g., GAPDH) [21]. It is involved in cellular homeostasis and is highly expressed in cancer, promoting proliferation, anti-apoptosis, and metastasis [22,23]. The multimerization of lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2a (LAMP2a) on the lysosomal membrane is crucial for binding with the chaperone protein HSP70 (Heat shock protein 70) through the lysosomal mTORC2 (mTOR complex 2)/PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase 1 (PHLPP1)/AKT1 (Serine/threonine-protein kinase 1) pathway [24]. Cuervo and her colleagues demonstrated that the lysosomal enzyme cathepsin A (CTSA) regulates the half-life of LAMP2a, the rate-limiting factor for CMA, through its degradation [25]. Mutations in the CTSA gene cause the lysosomal storage disorder galactosialidosis both in humans and dogs [26,27]. However, the association between leptin and CMTs has not yet been described. Moreover, although previous studies have described the relationship between cathepsins and leptin [28,29], CTSA has not been extensively studied in cancer metastasis. Therefore, in this study, we mainly focused on the alteration of metastasis of canine inflammatory mammary adenocarcinoma (CHMp) cells with leptin (with or without Allo-aca) and CTSA and further evaluated the alteration of CMA activity.

2. Results

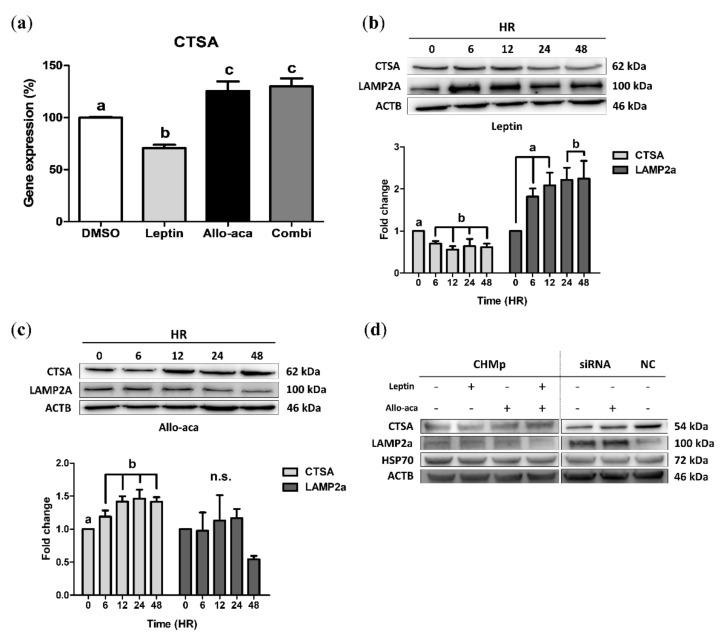

2.1. Leptin Downregulated CTSA and Upregulated LAMP2a in CHMp Cells

To determine the optimal concentration of leptin and Allo-aca, we introduced leptin into CHMp cells. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay showed that 6 nM leptin had a cell proliferation effect, while Allo-aca did not show this effect, even at 100 nM (the highest concentration) (Figure S1a,b). Interestingly, CTSA mRNA was significantly decreased with 12 nM leptin treatment and increased at the lowest concentration (1 nM) with Allo-aca (Figure S1c,d). Thus, we treated cells with 12 nM leptin and/or 100 nM Allo-aca to maximize its antagonistic effect. Real-time PCR analysis showed that gene expression was upregulated following treatment with Allo-aca, disregarding the presence of leptin (Figure 1a). Subsequently, the time-course immunoblot of CTSA and LAMP2a showed that leptin gradually downregulated CTSA from 6 h while significantly upregulating LAMP2a after 24 h (Figure 1b). Conversely, Allo-aca upregulated CTSA after 6 h of treatment, but no significance was observed in LAMP2a (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Leptin downregulated the cathepsin A (CTSA) gene in canine inflammatory mammary adenocarcinoma (CHMp) cells. (a) CTSA gene expression in CHMp cells treated with leptin and Allo-aca was evaluated using real-time PCR. (b,c) Western blot analysis of time-course CTSA/lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2a (LAMP2a) alteration induced by leptin (b) and Allo-aca (c) treatment. (d) Western blot analysis of chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA)-related genes. Cells were incubated with leptin and/or Allo-aca for 24 h, and CTSA small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) was transfected 24 h before chemical treatment. All graphs are visualized as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with at least three replicates. The column bars with different alphabetical letters indicate significant difference among groups (p < 0.05). Combi: combination of leptin and Allo-aca; NC: negative control siRNA.

As shown in Figure 1d, Allo-aca antagonized the effect of leptin in CHMp cells, resulting in decreased LAMP2a expression. To elucidate the role of leptin in CMA, we transfected CHMp cells with CTSA small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) (Figure S2). Immunoblot analysis showed that Allo-aca upregulated CTSA in the transfected cells, but the expression of LAMP2a was not significantly altered.

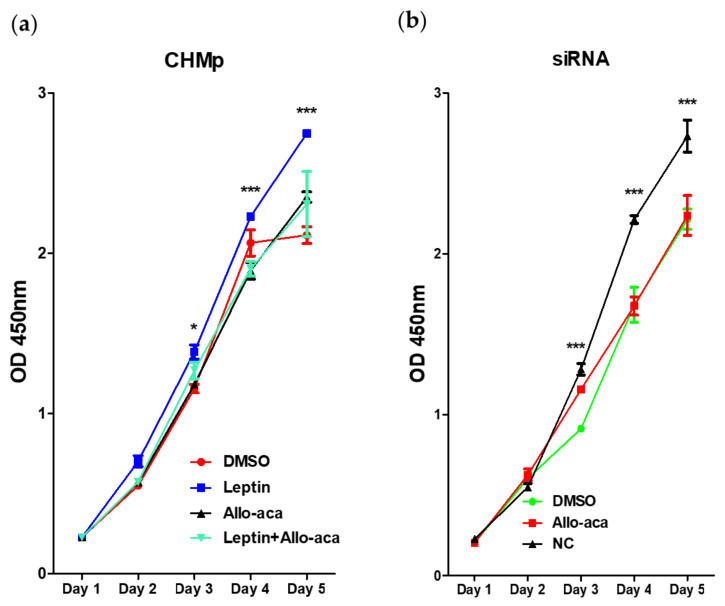

2.2. Leptin Promoted Cell Proliferation in CHMp Cells

Cell proliferation assay showed that the proliferation capacity of CHMp cells was significantly increased with 12 nM leptin treatment, and Allo-aca antagonized its effect (Figure 2a), resulting in a significantly lower proliferation index. Moreover, Allo-aca alone did not show a negative effect on cell proliferation, as no significant difference was observed between the control and Allo-aca groups. In agreement with the previous results, we also found that the knockdown of CTSA using siRNA inhibited cell proliferation, and that Allo-aca did not affect cell proliferation in transfected cells (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Cell proliferation assay. Quantitative measurement was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Five thousand cells per well were seeded and cultured for 5 days in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. (a) Leptin significantly promoted cancer cell proliferation from day 3, whereas Allo-aca inhibited its effect in CHMp cells. (b) Allo-aca treatment on CTSA siRNA-transfected cells did not affect cell proliferation. However, it seemed that the knockdown of CTSA decreased cell proliferation compared to the negative control group. The results were expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

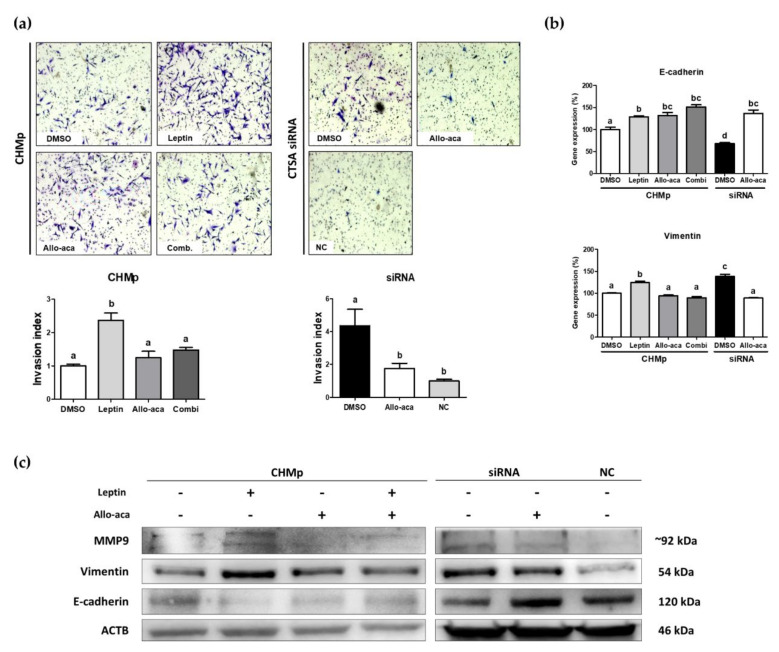

2.3. Leptin Stimulated EMT in CHMp Cells

To investigate the role of leptin in canine mammary adenocarcinoma progression, we introduced leptin and Allo-aca into CHMp cells. Matrigel invasion assay (Figure 3a) showed that the invasion capacities of CHMp cells were significantly increased by leptin treatment, while those of Allo-aca-treated cells (including the combination group) remained the same as the control group. In addition, siRNA-transfected cells showed significantly increased invasion capacities, but these were significantly reduced by treatment with Allo-aca.

Figure 3.

Leptin stimulated epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in CHMp cells. (a) Matrigel invasion assay and calculated invasion index of CHMp and siRNA-transfected cells. Invaded cells were counted under light microscopy (40×) using ImageJ software. (b) Comparison of EMT-related gene (E-cadherin and vimentin) expression using real-time PCR analysis among experimental groups. (c) Western blot analysis of tumor invasion-related genes. All graphs are visualized as mean ± SEM with at least three replicates. The column bars with different alphabetical letters indicate significant difference among groups (p < 0.05). Combi: combination of leptin and Allo-aca; NC: negative control siRNA.

Real-time PCR of EMT-related genes showed that both E-cadherin and vimentin were significantly altered by leptin treatment. Allo-aca significantly upregulated E-cadherin, a cell adhesion factor, in both CHMp cells and transfected cells. However, leptin and siRNA significantly upregulated vimentin, whereas its effect was inhibited by Allo-aca (Figure 3b).

To validate whether leptin alters EMT genes at the translational level, we also performed Western blot analysis (Figure 3c). The overall tendencies were matched with mRNA expression, but leptin and knockdown of CTSA significantly upregulated MMP9 (matrix metalloproteinase 9), a biomarker of tumor invasion and metastasis [30]. In addition, Allo-aca downregulated vimentin and MMP9 and upregulated E-cadherin in both cell types. Taken together, these results suggest that leptin and subsequent CTSA downregulation stimulate tumor invasion and metastasis via activation of the EMT process.

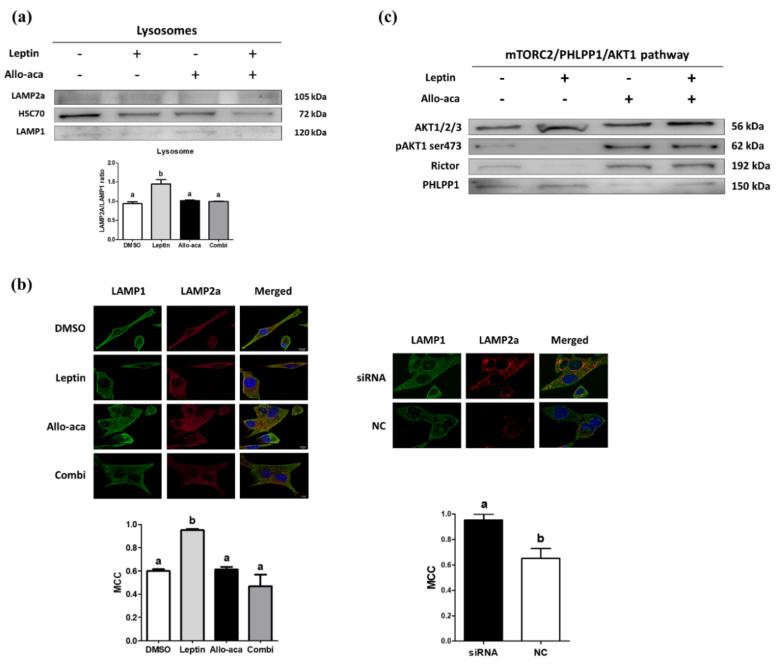

2.4. Leptin Delayed the Degradation of LAMP2a Through Downregulation of CTSA

To specifically investigate the alteration of lysosomal proteins, we isolated lysosome fractions from CHMp cells. We found that the LAMP2a/LAMP1 ratio increased with leptin treatment, and no significant differences were observed among the DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide), Allo-aca, and combination groups (Figure 4a). In addition, HSC70 (Heat shock cognate 71kDa protein), LAMP2a, and LAMP1 colocalization tests analyzed with Mander’s colocalization coefficient (MCC) demonstrated that leptin and knockdown of CTSA increased the ratio, while Allo-aca showed no agonistic effect and an antagonistic effect on leptin (Figure 4b). On the basis of these results, we can assume that leptin and subsequent downregulation of CTSA are possibly correlated with higher CMA activity.

Figure 4.

Leptin induced a higher LAMP2a/LAMP1 ratio in lysosomal membranes. (a) Western blot analysis of lysosomes isolated from CHMp cells targeting CMA-associated lysosomal proteins. The results showed that the LAMP2a/LAMP1 ratio was increased with leptin treatment and Allo-aca acted as a leptin receptor (OBR) antagonist. Then, the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. (b) Leptin and Allo-aca-treated CHMp cells and CTSA siRNA were visualized with confocal microscopy with immunofluorescence technique. The colocalization ratio was measured by Fiji software developed by Schindelin and colleagues [31] and analyzed on the basis of Mander’s colocalization coefficient (MCC). The results were in concordance with the lysosome immunoblot experiments. (c) Western blot analysis of the lysosomal mTORC2/PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase 1 (PHLPP1)/AKT1 pathway in lysosomes isolated from CHMp cells. pAKT1(ser473) and rictor were inhibited with leptin treatment, but PHLPP1 was stimulated. All graphs are visualized as mean ± SEM with at least three replicates. The column bars with different alphabetical letters indicate significant difference among groups (p < 0.05). Combi: combination of leptin and Allo-aca; NC: negative control siRNA.

2.5. Leptin May Promote Lysosomal LAMP2a Multimerization Through the mTORC2/PHLPP1/AKT1 Pathway

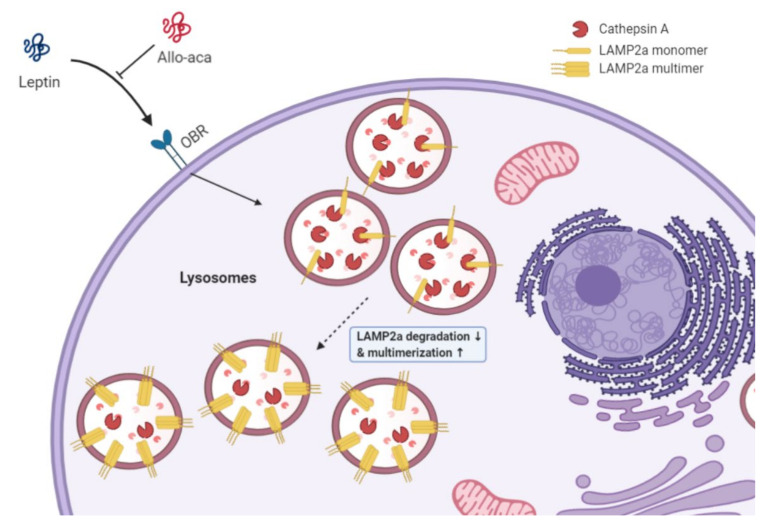

To further investigate the role of leptin in the regulation of CMA, we analyzed the lysosomal kinase/phosphatase complex. We found that leptin downregulates rictor, a subunit of the mTORC2 complex, and upregulates PHLPP1, a serine/threonine phosphatase, inhibiting the action of AKT1 via phosphorylation of pAKT1(ser473). Conversely, similar to the previous results, Allo-aca antagonized these effects regardless of the presence of leptin (Figure 4c). Thus, we can suggest that leptin promotes the multimerization of LAMP2a in lysosomal membranes through the activation of the mTORC2/PHLPP1/AKT1 pathway and that Allo-aca can prevent the formation of LAMP2a multimers (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic images describing the summarized results in this study. Leptin downregulated CTSA and, following delayed LAMP2a degradation, resulted in CMA activation and stimulation of LAMP2a multimerization through the mTORC2/PHLPP1/AKT1 pathway.

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the concurrent effects of leptin on the lysosomal enzyme CTSA and the following effects on tumor cell proliferation and invasion capacity of CHMp, a canine mammary adenocarcinoma cell line. In our preliminary study, we found that CTSA gene expression was significantly downregulated and enhanced cell viability with 12 nM leptin treatment, which was reversed with the OBR antagonist Allo-aca. Interestingly, Allo-aca itself could also inhibit EMT and metastasis in both cell types. Moreover, the increased expression of MMP9 indicates a higher chance of metastasis to other organs [32]. To determine the effect of leptin on CTSA, we applied CTSA siRNA to knock down its expression in CHMp cells. In addition, we also found that leptin promotes tumor cell growth, which is significant in other control and experimental groups in the time-course cell proliferation assay. Interestingly, the knockdown of CTSA did not promote tumor cell proliferation but rather inhibited it. As patients with galactosialidosis typically show lower body weight, we suspect that higher LAMP2a activity due to delayed degradation is responsible for a slower proliferation rate [25]. Moreover, Allo-aca inhibited leptin-induced cell proliferation in the co-treatment group but did not inhibit the growth itself, and no alteration was observed in transfected cells. Therefore, we focused on utilizing leptin and Allo-aca to investigate the role of CTSA in CHMp cells.

We subsequently investigated leptin as a therapeutic target for preventing mammary cancer metastasis in dogs and identified it as an endogenous LAMP2a activator by modulating its stability and promoting multimerization. An in vitro invasion assay showed that leptin and knockdown of CTSA promoted CHMp cell invasion by upregulating vimentin and metallo-proteinase 9 (MMP9), and downregulating E-cadherin. In addition, supplementation of Allo-aca antagonized the effect of leptin on EMT even without leptin co-treatment. E-cadherin, a transmembrane epithelial cell marker, is considered a prognostic factor in both human and dog mammary gland cancer [33,34]. Its decreased expression represents upregulated cancer invasion ability and poor prognosis, causing EMT progression together with increased expression of vimentin, a mesenchymal cell marker. The radical knockdown of CTSA also induced EMT, similar to leptin treatment. On the basis of the ability to induce EMT, we found leptin and its ability to downregulate CTSA to promote the migration and invasiveness of CHMp cells and upregulate metastasis-related genes, which shows poor prognosis for mammary gland tumor patients. In addition, we also found that Allo-aca antagonized leptin in CHMp cells but also reversed the consequences of the knockdown of CTSA and further showed anti-EMT effects. Therefore, these results indicate that leptin may also induce metastasis in canine mammary adenocarcinoma cells and that Allo-aca seems to have anti-metastatic properties retrieving CTSA expression, which prolongs the half-life of LAMP2a.

It has been suggested that the knockdown of LAMP2a, which induces lower CMA, reduces the metastatic capacity of lung cancer cells [22]. In other words, the level of CMA in cancer cells is associated with cancer metastasis. In agreement with the previous study, the upregulation of LAMP2a through knockdown or leptin treatment in CHMp cells resulted in enhanced invasion and metastasis. These alterations were prevented with Allo-aca treatment and reduced LAMP2a ratio normalized by LAMP1 (LAMP2a/LAMP1 ratio) significantly. That is, the prolonged LAMP2a half-life results in a higher level of LAMP2a on the lysosomal membrane. Moreover, leptin stimulated PHLPP1, thus showing inhibitory effects on AKT. PHLPP1 is known to inhibit CMA activity through AKT dephosphorylation. In addition, phosphorylated AKT1 ser473 (pAKT1(ser473)) is lower in CMA-active lysosomes in starved animals [24]. Together with these findings, we conclude that leptin also promotes CMA activity through LAMP2a multimerization (Figure 5). Moreover, Allo-aca can offset its effects in CHMp cells by blocking OBR.

Higher levels of LAMP2a in cancers play important roles in cell survival and their microenvironment. Therefore, previous studies have focused on LAMP2a as a therapeutic target. However, specific manipulation of one specific gene or protein using RNAi (RNA interference) can result in unpredictable side effects such as RNAi off-target effects and carrier-mediated toxicity [35,36], which can be rather fatal for veterinary patients. Therefore, through Allo-aca treatment, which can offset the CMA-stimulating effect of leptin demonstrated in this study, we suggest the possibility of inhibiting metastasis with relatively few side effects in the treatment of cIMCs. However, the fact that Allo-aca itself can enter the blood–brain barrier must be improved because it can stimulate appetite and weight gain.

Although canine inflammatory mammary adenocarninoma has not been studied much, in terms of the subject, CHMp is a relatively well-phenotyped cell line and thus can represent the alterations of cIMCs shown in the study with leptin and Allo-aca. However, the single use of CHMp cell line cannot represent the definitive physiology of all types (epithelial, myoepithelal, mesenchymal) of CMTs because the cell line is of an epithelial origin. Moreover, the lack of direct confirmation of CMA activity as a substrate and the inability to quantitatively analyze LAMP2a multimerization using blue native PAGE due to the absence of suitable antibodies are limitations in this study. Further studies on samples from mammary adenocarcinoma patients and their retrospective studies are needed to assess clinical validity of Allo-aca as an anti-metastases agent.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Cell Culture Methods

The CHMp cell line was generously donated by Professor So Young Lee from the Department of Veterinary Pharmacology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea. The cells were originally isolated from the primary lesions of 12-year-old mixed-breed female inflammatory mammary adenocarcinoma and established as a cell line by Professor Nobuo Sasaki from the University of Tokyo [37]. The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% charcoal-dextran treated fetal bovine serum (both from Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA), and 0.5% gentamicin (Merck), in a 5% carbon dioxide 37 °C incubator.

4.2. Chemicals and Antibodies

Canine leptin was purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and Allo-aca (H-alloThr-Glu-Nva-Val-Ala-Leu-Ser-Arg-Aca-NH2), developed by Otvos et al. [38], was synthesized by Koma Biotechnology (Seoul, Korea). DMSO was used as their solvent and the control group. Co-treatment of leptin and Allo-aca is described as Combi in this study. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise stated. The antibodies used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in this study.

| Target | Catalog Number | Host | Clone | Dilution | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP2a | ab18528 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:1000 | Abcam |

| LAMP1 | ab24170 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:1000 | Abcam |

| HSP70 | ab53496 | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:1000 | Abcam |

| VIM | ab1316 | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:400 | Abcam |

| MMP9 | ab38898 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:1000 | Abcam |

| pAKT1(ser473) | ab81283 | Rabbit | Monoclonal | 1:5000 | Abcam |

| ACTB | ab8227 | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:5000 | Abcam |

| CDH1 | 14-3249-82 | Rat | Monoclonal | 1:250 | Invitrogen |

| AKT1 | sc-135829 | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:1000 | SCBT |

| PHLPP1 | sc-390129 | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:500 | SCBT |

| mTOR | sc-517464 | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:200 | SCBT |

| CTSA | 139645 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:1000 | US Biological |

4.3. Reverse siRNA Transfection

Cathepsin A siRNA (CTSA siRNA) was transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Before seeding the cells in 6-well dishes, we diluted 50 pmol of CTSA siRNA in 500 µL Opti-MEM (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) with the addition of 7 µL of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). After 20 min of incubation at room temperature, 300,000 CHMp cells were seeded and incubated for 24 h and then used for further experiments. The siRNA sequences are listed in Table S1.

4.4. Cell Proliferation Assay

Five thousand cells per well were seeded in a 96-well dish with phenol red-free RPMI-1640 and 10% FBS (Fetal bovine serum) and treated with 12 nM leptin and 100 nM Allo-aca for 5 days to exclude the interference of phenol red. Each day, the whole medium was discarded and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, 10 µL of 12 mM MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) in 100 µL phenol red-free RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) were added and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C to form the formazan crystals. After incubation, 85 µL of MTT-containing media was discarded, and 80 µL of DMSO was added as a solvent to dissolve the formazan for 10 min at 37 °C following horizontal shaking for 30 min in the dark. The technical replicates of each variable were repeated 4 times. The samples were analyzed at 450 nm using a Tecan Sunrise Microplate Reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

4.5. Cell Invasion Assay

The cultured cells were treated with non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min to detach cells without damaging cell surface receptors. Suspended cells were subjected to a cell invasion assay using 8 µm BioCoat Matrigel invasion chambers (Corning, Bedford, MA, USA). Cells (2 × 105) were seeded in each well with RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS and incubated for 22 h. After incubation, the upper membrane was swabbed with sterile cotton swabs to remove non-invading cells and stained with Diff-Quick solution (Sysmax, Tokyo, Japan). The invaded cells were counted under a 40 × bright microscope and counted with ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.6. RNA Extraction and Real-time Quantitative PCR Analysis (RT-qPCR)

After 24 h of incubation with the addition of leptin and/or Allo-aca, the cells were collected for RNA extraction. We used an easy-spin Total RNA Extraction Kit, and complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using the Maxime RT PreMix Kit (both kits from Intron Biotechnology, Gyeonggi, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For RT-qPCR analysis, we used 2× SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA) as a probe, and the primer sequences are listed in Table 2. Amplification was performed using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA) with reactions containing 50 ng cDNA, 10 pmol of forward and reverse primers, 10 μL of SYBR green premix, and nuclease-free water in each well. The thermocycling protocol was 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 40 s. All reaction cycles were conducted in a MicroAmp Optical 96-Well Reaction Plate (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA). To compare mRNA expression based on leptin and Allo-aca treatment in CHMp cells, we normalized mRNA expression to the housekeeping gene β-actin (ΔCt), and the relative amount of each transcript was quantified in at least 3 replicates using the following equation: relative quantity (R) = 2−(ΔCt sample−ΔCt control).

Table 2.

Primers and their sequences used in this study. 1 CDH1 is also known as E-cadherin.

| Gene | GenBank Accession No. |

Primer Sequences | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTSA | NM_001109915.1 | F: 5′-CAG ACC CAC TGC TGT TCT CA-3′ | 56 |

| R: 5′-CTG CAG ATT TGT CAC GCA TT-3′ | |||

| R: 5′-GAG TAC TTC AGG GCC GTC AG-3′ | |||

| VIM | NM_001287023.1 | F: 5′-CCG ACA GGA TGT TGA CAA TG-3′ | 116 |

| R: 5′-GCT CCT GGA TTT CCT CAT CA-3′ | |||

| CDH1 1 | NM_001287125.1 | F: 5′-AAT GAC CCA GCT CGT GAA TC-3′ | 108 |

| R: 5′-CAC CTG GTC CTT GTT CTG GT-3′ | |||

| ACTB | NM_001195845.2 | F: 5′-GCG CAA GTA CTC TGT GTG GA-3′ | 65 |

| R: 5′-ACA TTT GCT GGA AGG TGG AC-3′ |

F: Forward; R: Reverse

4.7. Immunofluorescence Analysis

The cells were seeded in 8-well SPL Cell Culture (SPL Life Science, Gyeonggi, Korea) at a density of 5000 cells per well. After 6 h of incubation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 diluted in PBS for 10 min. One percent bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS-Tween 20 was used for blocking for 1 h, and primary antibodies against LAMP1 (diluted 1:200 in PBS-T with 1% BSA) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day, goat anti-rabbit IgG (Immunoglobulin G) H&L Alexa Fluor 488 antibody against LAMP1 primary antibodies was added for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. For the anti-LAMP2a antibody, the antibody was manually conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 Conjugation Kit-Lightning-Link (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) to visualize colocation of LAMP1 and LAMP2a despite the same antibody origin, and incubated overnight in the dark. The slides were then washed with ice-cold PBS and then mounted with Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, United Kingdom). All images were obtained using a Ti2-E confocal microscopy system (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The negative control images are attached in Figure S3.

4.8. Lysosome Isolation and Immunoblot

CHMp cells were cultivated in 148.2 mm dishes at a density of 5 × 106 and then treated with 0.01% DMSO (control), leptin (12 nM), Allo-aca (100 nM), or combination of leptin and Allo-aca. After treatment with chemicals, the cells were collected with disposable cell scrapers. Lysosomes were then isolated from cells using the Minute Lysosome Isolation Kit (Invent Biotechnologies, Plymouth, MN, USA) on the basis of the spin-column method. Approximately 1.0 × 108 cells were subjected to lysosome isolation. The isolated lysosomes were resuspended in RIPA (Radioimmuno-precipitation assay) buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with a protein inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor to prevent protein degradation, blocking the activity of phosphatases, and were centrifuged at 16,000× g for 30 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5 mL tube and subjected to protein quantification using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Lysosome lysates (10 μg) were loaded onto 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast gels. After transfer and blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary overnight and developed with HRP (Horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated secondary antibodies.

4.9. Western Blot Analysis

For time-course investigation of CTSA and LAMP2a, we collected the samples at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48, h of incubation with leptin and Allo-aca to assess the alteration of CMA-related factors. For EMT pathway investigation, the samples were collected at 24 h of incubation. The samples were lysed with PRO-PREP Protein Extraction Solution (Intron Biotechnology, Gyeonggi, Korea), and their protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay. For SDS-PAGE, 5 µg of each sample was loaded onto each well of 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and paged at 100 V for 1 h 30 min. The samples were then transferred to 0.45 µm methanol-activated polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) at 350 mA for 1 h 10 min. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk solution and washed 3 times each with TBS-T for 10 min, followed by primary antibody incubation overnight. The next day, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. For primary antibodies, we used rabbit anti-LAMP1, LAMP2a, cathepsin A (PPCA), mouse anti-HSP70, β-actin, PHLPP1, AKT1, pAKT1(ser473), and rat anti-E-cadherin (CDH1).

For time-course investigation of CTSA and LAMP2a, we collected the samples at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48, h of incubation with leptin and Allo-aca to assess the alteration of CMA-related factors. For EMT pathway investigation, the samples were collected at 24 h of incubation. The samples were lysed with PRO-PREP Protein Extraction Solution (Intron Biotechnology, Gyeonggi, Korea), and their protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay. For SDS-PAGE, 5 µg of each sample was loaded onto each well of 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and paged at 100 V for 1 h 30 min. The samples were then transferred to 0.45 µm methanol-activated polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) at 350 mA for 1 h 10 min. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk solution and washed 3 times each with TBS-T for 10 min, followed by primary antibody incubation overnight. The next day, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. For primary antibodies, we used rabbit anti-LAMP1, LAMP2a, cathepsin A (PPCA), mouse anti-HSP70, β-actin, PHLPP1, AKT1, pAKT1(ser473), and rat anti-E-cadherin (CDH1).

4.10. Statistical Analysis

The raw data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) with one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test for further analysis. The Western blot and immunocytochemistry images were analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institute of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA) according to NIH guidelines.

5. Conclusions

From our findings, we suggest that leptin, which increases with age and obesity in dogs, can stimulate mammary gland cancer metastasis by elongating the half-life and multimerization of LAMP2a. We also demonstrated that Allo-aca can reverse the promotion of EMT and invasiveness of CHMp cells treated with leptin through selective pairing to OBR without any agonistic effects. These findings provide evidence that leptin receptor antagonists are a therapeutic and prophylactic option for cIMCs without unwanted side effects.

Acknowledgments

We deeply thank So Young Lee from Seoul National University for providing the CHMp cell line. We also thank Ye Sual Yun and Hyo Kyung Yu for their technical help. We hope that this work will help veterinary and human patients fight cancer as well as enhance their quality of life.

Abbreviations

| CMT | Canine mammary gland tumor |

| cIMC | Canine inflammatory mammary carcinoma |

| CTSA | Lysosomal protective protein cathepsin A (PPCA) |

| LAMP1 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 |

| LAMP2a | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2a |

| CMA | Chaperone-mediated autophagy |

| OBR | Leptin receptor |

| PHLPP1 | PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase 1 |

| ACTB | Beta-actin |

| VIM | Vimentin |

| CDH1 | E-cadherin |

| siRNA | Small interfering ribonucleic acid |

| cDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/23/8963/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-W.K.; methodology, J.-W.K.; software, J.-W.K.; validation, J.-W.K. and G.A.K., formal analysis, J.-W.K.; investigation, J.-W.K. and F.Y.M.; resources, J.-W.K. and G.A.K.; data curation, J.-W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-W.K.; writing—review and editing, J.-W.K., F.Y.M.; visualization, J.-W.K.; supervision, G.A.K.; project administration, G.A.K.; funding acquisition, G.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Center for Companion Animal Research (CCAR), Rural Development Administration, Korea, grant number PJ014990022020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Moschos S., Chan J.L., Mantzoros C.S. Leptin and reproduction: A review. Fertil. Steril. 2002;77:433–444. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)03010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegel K., Tasali E., Penev P., Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004;141:846–850. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garofalo C., Surmacz E. Leptin and cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2006;207:12–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nepal S., Kim M.J., Hong J.T., Kim S.H., Sohn D.H., Lee S.H., Song K., Choi D.Y., Lee E.S., Park P.H. Autophagy induction by leptin contributes to suppression of apoptosis in cancer cells and xenograft model: Involvement of p53/FoxO3A axis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7166–7181. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan D., Avtanski D., Saxena N.K., Sharma D. Leptin-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells requires beta-catenin activation via Akt/GSK3- and MTA1/Wnt1 protein-dependent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:8598–8612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei L., Li K., Pang X., Guo B., Su M., Huang Y., Wang N., Ji F., Zhong C., Yang J., et al. Leptin promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer via the upregulation of pyruvate kinase M2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;35:166. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0446-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng H., Liu Q., Zhang N., Zheng L., Sang M., Feng J., Zhang J., Wu X., Shan B. Leptin promotes metastasis by inducing an epithelial-mesenchymal transition in A549 lung cancer cells. Oncol. Res. 2013;21:165–171. doi: 10.3727/096504014X13887748696662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu M., Cao F.L., Li N., Gao X., Su X., Jiang X. Leptin induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via activation of the ERK signaling pathway in lung cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018;16:4782–4788. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Candelaria P.V., Rampoldi A., Harbuzariu A., Gonzalez-Perez R.R. Leptin signaling and cancer chemoresistance: Perspectives. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;8:106–119. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i2.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otvos L., Jr., Kovalszky I., Riolfi M., Ferla R., Olah J., Sztodola A., Nama K., Molino A., Piubello Q., Wade J.D., et al. Efficacy of a leptin receptor antagonist peptide in a mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2011;47:1578–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alenza M.D.P., Pena L., del Castillo N., Nieto A.I. Factors influencing the incidence and prognosis of canine mammary tumours. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2000;41:287–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2000.tb03203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isidori A.M., Strollo F., More M., Caprio M., Aversa A., Moretti C., Frajese G., Riondino G., Fabbri A. Leptin and aging: Correlation with endocrine changes in male and female healthy adult populations of different body weights. J. Clin. Endocr Metab. 2000;85:1954–1962. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.5.6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim H.Y., Im K.S., Kim N.H., Kim H.W., Shin J.I., Yhee J.Y., Sur J.H. Effects of Obesity and Obesity-Related Molecules on Canine Mammary Gland Tumors. Vet. Pathol. 2015;52:1045–1051. doi: 10.1177/0300985815579994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishioka K., Hosoya K., Kitagawa H., Shibata H., Honjoh T., Kimura K., Saito M. Plasma leptin concentration in dogs: Effects of body condition score, age, gender and breeds. Res. Vet. Sci. 2007;82:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishioka K., Soliman M.M., Sagawa M., Nakadomo F., Shibata H., Honjoh T., Hashimoto A., Kitamura H., Kimura K., Saito M. Experimental and clinical studies on plasma leptin in obese dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2002;64:349–353. doi: 10.1292/jvms.64.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray M., Meehan J., Martinez-Perez C., Kay C., Turnbull A.K., Morrison L.R., Pang L.Y., Argyle D. Naturally-Occurring Canine Mammary Tumors as a Translational Model for Human Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:617. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez Alenza M.D., Tabanera E., Pena L. Inflammatory mammary carcinoma in dogs: 33 cases (1995–1999) J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001;219:1110–1114. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.219.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen L.N. A comparative study of canine and human breast cancer. Investig. Cell Pathol. 1979;2:257–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammed S.I., Utturkar S., Lee M., Yang H.H., Cui Z., Lanman N.A., Zhang G., Cardona X.E.R., Mittal S.K., Miller M.A. Ductal Carcinoma In Situ Progression in Dog Model of Breast Cancer. Cancers. 2020;12:418. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein N., Haim Y., Mattar P., Hadadi-Bechor S., Maixner N., Kovacs P., Bluher M., Rudich A. Leptin stimulates autophagy/lysosome-related degradation of long-lived proteins in adipocytes. Adipocyte. 2019;8:51–60. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2019.1569447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dice J.F. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;3:295–299. doi: 10.4161/auto.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kon M., Kiffin R., Koga H., Chapochnick J., Macian F., Varticovski L., Cuervo A.M. Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy Is Required for Tumor Growth. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:109ra117. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saha T. LAMP2A overexpression in breast tumors promotes cancer cell survival via chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:1643–1656. doi: 10.4161/auto.21654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arias E., Koga H., Diaz A., Mocholi E., Patel B., Cuervo A.M. Lysosomal mTORC2/PHLPP1/Akt Regulate Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:270–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuervo A.M., Mann L., Bonten E.J., d’Azzo A., Dice J.F. Cathepsin A regulates chaperone-mediated autophagy through cleavage of the lysosomal receptor. EMBO J. 2003;22:47–59. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knowles K., Alroy J., Castagnaro M., Raghavan S.S., Jakowski R.M., Freden G.O. Adult-onset lysosomal storage disease in a Schipperke dog: Clinical, morphological and biochemical studies. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;86:306–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00304147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caciotti A., Catarzi S., Tonin R., Lugli L., Perez C.R., Michelakakis H., Mavridou I., Donati M.A., Guerrini R., d’Azzo A., et al. Galactosialidosis: Review and analysis of CTSA gene mutations. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2013;8:114. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naour N., Rouault C., Fellahi S., Lavoie M.E., Poitou C., Keophiphath M., Eberle D., Shoelson S., Rizkalla S., Bastard J.P., et al. Cathepsins in human obesity: Changes in energy balance predominantly affect cathepsin s in adipose tissue and in circulation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95:1861–1868. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveira M., Assis D.M., Paschoalin T., Miranda A., Ribeiro E.B., Juliano M.A., Bromme D., Christoffolete M.A., Barros N.M., Carmona A.K. Cysteine cathepsin S processes leptin, inactivating its biological activity. J. Endocrinol. 2012;214:217–224. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a Cancer Biomarker and MMP-9 Biosensors: Recent Advances. Sensors. 2018;18:3249. doi: 10.3390/s18103249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Darlix A., Lamy P.J., Lopez-Crapez E., Braccini A.L., Firmin N., Romieu G., Thezenas S., Jacot W. Serum NSE, MMP-9 and HER2 extracellular domain are associated with brain metastases in metastatic breast cancer patients: Predictive biomarkers for brain metastases? Int. J. Cancer. 2016;139:2299–2311. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gama A., Paredes J., Gartner F., Alves A., Schmitt F. Expression of E-cadherin, P-cadherin and beta-catenin in canine malignant mammary tumours in relation to clinicopathological parameters, proliferation and survival. Vet. J. 2008;177:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z., Yin S., Zhang L., Liu W., Chen B. Prognostic value of reduced E-cadherin expression in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:16445–16455. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lv H., Zhang S., Wang B., Cui S., Yan J. Toxicity of cationic lipids and cationic polymers in gene delivery. J. Control. Release. 2006;114:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue H.Y., Liu S., Wong H.L. Nanotoxicity: A key obstacle to clinical translation of siRNA-based nanomedicine. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:295–312. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uyama R., Nakagawa T., Hong S.H., Mochizuki M., Nishimura R., Sasaki N. Establishment of four pairs of canine mammary tumour cell lines derived from primary and metastatic origin and their E-cadherin expression. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2006;4:104–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5810.2006.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otvos L., Kovalszky I., Scolaro L., Sztodola A., Olah J., Cassone M., Knappe D., Hoffmann R., Lovas S., Hatfield M.P.D., et al. Peptide-Based leptin Receptor Antagonists for Cancer Treatment and Appetite Regulation. Biopolymers. 2011;96:117–125. doi: 10.1002/bip.21377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.