Abstract

During the COVID-19 outbreak, which is effective worldwide, the psychological conditions of healthcare professionals deteriorate. The aim of this study was to examine health professionals’ changes in their sexual lives due to the COVID-19 outbreak in Istanbul, Turkey. This online survey was conducted between 2 and 26 May 2020 with 232 healthcare professionals working in a pandemic hospital. After obtaining informed consent, a questionnaire was sent online from the hospital database and health institutions social media accounts (Twitter®, Facebook®, Instagram®, WhatsApp® etc.) and e-mail addresses. The first section of the four-part questionnaire included demographic data, the second and third sections of pre-and post-COVID-19 attitudes, and the last section to assess sexual functions (International Index of Erecile Function for male and Female Sexual Function Index for female), anxiety and depression. Dependent sample t-test, Mc Nemar test, and multivariate analysis were used.The study was completed with 185 participants in total. Healthcare workers’ sexual desire (3.49 ± 1.12 vs. 3.22 ± 1.17; p = 0.003), weekly sexual intercourse/masturbation number (2.53 ± 1.12 vs. 1.32 ± 1.27; p < 0.001), foreplay time (16.38 ± 12.35 vs. 12.02 ± 12.14; p < 0.001), sexual intercourse time (24.65 ± 19.58 vs. 19.38 ± 18.85; p < 0.001) decreased compared to the Pre-COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, participants prefer less foreplay (p < 0.001), less oral sex (p < 0.001) and anal sex (p = 0.007) during COVID-19 and more non-face to face sexual intercourse positions (p < 0.001). When factors affecting sexual dysfunction were analyzed as univariate and multivariate, sexual dysfunction was shown to be significantly more common in males (OR = 0.053) and alcohol users (OR = 2.925). During the COVID-19 outbreak, healthcare workers’ sexual desires decreased, the number of sexual intercourses decreased, their foreplay times decreased, and their sexual intercourse positions changed to less face to face.

Subject terms: Quality of life, Risk factors

Introduction

At the end of December 2019, a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) has been identified as the cause of a cluster of pneumonia cases in city of Wuhan, Hubei Province, China and has caused a COVID-19 outbreak [1]. COVID-19 is a respiratory virus that is contagious through direct contact with large respiratory droplets or secretions of infected people [2]. The rate of its spread has been gradually increasing in the United States and Europe. Approximately 5 million people worldwide have been infected and the number of COVID-19 deaths has exceeded 300,000 [3].

Social isolation can lead to widespread fear, anxiety, and panic, which can lead to further negative effects, including depression and sexual dysfunction. The sexual attitudes of the healthcare workers who are most in contact with the virus are unknown.

Healthcare professionals who are not directly related to COVID-19 worldwide are also assigned to acute care departments such as intensive care unit or emergency room from clinical specialties in other departments [4]. Healthcare professionals are those with the most contact with the virus in this outbreak. It has been found that 35.5% of the workers were positive in the study in which PCR positivity of healthcare professionals was evaluated [5].

Although the spread of the virus with body fluids is known, there is not yet sufficient evidence that the virus is isolated in sperm and vaginal fluid [6]. Close contact of partners due to the nature of sexual intercourse may affect the transmission of the virus to one another. Healthcare professionals may be concerned about transmitting the virus they received from the hospital to their partners.

While there are studies evaluating healthcare workers’ attitudes toward virus protection in the literature [7, 8], there are no studies on sexual life attitudes. The purpose of this cross-sectional study is to examine health workers’ changes in their sexual lives due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Other purposes of the study are to examine the status of maintaining sexual life and the use of contraceptive methods of healthcare workers.

Method

This cross-sectional, online survey evaluated the sexual attitudes of healthcare professionals working in a Pandemic Hospital, in Istanbul, Turkey, during the COVID-19 outbreak between 2 and 26 May, 2020. Between these dates, temporary restrictions (such as weekend lockdown) were taken by the government.

The study was accepted by the local ethics committee under the Institutional Review Board (IRB) number 130/2020. Inform consent was obtained from all participants. The study was designed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The article was designed as specified in the CHERRIES criteria [9].

Inclusion criteria in the study were 18 years and older, working in pandemic hospitals, married or having a regular sexual relationship (lasting at least 6 months) and agreeing to participate in the study. Participants who do not have an active sexual relationship, who were under 18 years of age, who do not work in a pandemic hospital, who underwent radical pelvic surgery and/or who received radiotherapy or any treatment due to sexual dysfunction (phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor, dapoxetine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, flibanserin, etc.) were excluded.

After obtaining the permission of healthcare professionals, a questionnaire was sent online from the hospital database and health institutions’ social media accounts (Twitter®, Facebook®, Instagram®, WhatsApp® etc.) and e-mail addresses. With the completion of the study online, it is aimed not to share sex life answers and other information without shame with third parties. The first part of the four-part questionnaire is about the demographic characteristics of the participants, the second part is about the sexual life attitudes before the COVID-19 outbreak (sexual intercourse frequency, sexual intercourse time, foreplay time, frequent positions, methods of protection). The third part, covering the period after the COVID-19 outbreak occurred in our country, is about the changes in participants’ sexual attitudes (relationship frequency, sexual intercourse time, foreplay duration, frequent positions, contraception methods, contagion concerns, social media usage status for communication with the opposite sex). In the last part, validated questionnaires are asked to determine the sexual functions, anxiety and depression levels of the participants.

The international erectile function index (IIEF), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-1 (STAI-1), STAI-2 and BECK depression inventory will be used for men. For women, a 19-question female sexual function index (FSFI), STAI-1, STAI-2 and BECK depression inventory will be used.

IIEF is a questionnaire developed by Rosen et al. [10] to question on sexual functions. With this questionnaire, 15 questions that determine the participants’ erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction status are asked and these 5 different sexual function areas are scored according to the answers received (erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction). The total score under the erectile function subdivision is below 25, which is defined as erectile dysfunction [11]. Turkish validation was done in 2002 by the Turkish Andrology Association [12].

FSFI consists of 19 questions and 6 subdomains and determines the sexual function status of women [13]. While a maximum of 36 points can be obtained from the survey, a score below 26.55 indicates sexual dysfunction [14]. Turkish validity was made in 2005 [15].

The sexual desire levels of the participants were evaluated by asking IIEF 12th question and FSFI 2nd question.

The State Anxiety Inventory (STAI-1 and 2) consists of two 20 items. Answers range from 1 to 4. The total score value obtained from the scale is between 20 and 80. A high score indicates the anxiety level is high [16]. Linguistic validation was published in 1985 [17].

The BECK depression scale was used to evaluate the degree of depression. In the survey consisting of 21 questions, a score between 0–63 is obtained [18, 19].

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 21.0 (IBM, NY, USA) program was used for statistical analysis. The normality of the distribution was evaluated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Mean and standard deviation values and percentages were specified. Changes before and after COVID-19 were evaluated with a dependent sample t-test, Wilcoxon test, chi-square test and Mc Nemar test. ANOVA test was used for evaluation between the units worked. Univariate and multivariate regression analysis were used for factors affecting sexual dysfunction. A significant p value was <0.05.

Results

The questionnaire was sent to 232 participants. Thirty-one of the participants were excluded from the study due to the lack of active sexual intercourse for the last 6 months, 13 could not complete the questionnaire questions and 3 received radiotherapy due to pelvic cancer (2 over cancer, 1 testis cancer). The study was completed with 185 participants in total. The response rate of the study is 79.74%.

The average age of the participants was 30.65 ± 5.99 (18–53) years and the average of BMI was 24.49 ± 4.03 (16.80–39.45). Eighty-nine (48.1%) of the health workers who completed the questionnaire were women and 96 (51.9%) were men. In total, 4 participants had COVID-19 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| n | % | Min–Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 89 | 48.1 | ||

| Male | 96 | 51.9 | ||

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 30.65 ± 5.99 | 18–53 | ||

| Height (Mean ± SD) | 172.60 ± 12.39 | 154–195 | ||

| Weight (Mean ± SD) | 73.31 ± 15.12 | 43–125 | ||

| BMI (Mean ± SD) | 24.49 ± 4.03 | 16.80–39.45 | ||

| Department | ||||

| COVID clinic | 48 | 25.9 | ||

| COVID outpatient clinic | 42 | 22.7 | ||

| COVID emergency | 43 | 23.2 | ||

| COVID ICU | 48 | 25.9 | ||

| Other | 4 | 2.2 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 93 | 50.3 | ||

| Married | 92 | 49.7 | ||

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| High school | 12 | 6.5 | ||

| University | 172 | 93.0 | ||

| Income level | ||||

| Low | 4 | 2.2 | ||

| Average | 35 | 18.9 | ||

| High | 145 | 78.4 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 37.8 | ||

| No | 115 | 62.2 | ||

| Alcohol status | ||||

| Yes | 85 | 45.9 | ||

| No | 100 | 54.1 | ||

| Cronic disease | ||||

| No | 150 | 81.1 | ||

| Hypertension | 3 | 1.6 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 7 | 3.8 | ||

| Cardiac disease | 5 | 2.7 | ||

| Thyroid disease | 10 | 5.4 | ||

| Neurological disease | 9 | 4.9 | ||

| COVID-19(+) | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 2.2 | ||

| No | 181 | 97.8 | ||

| Has anyone been diagnosed with Covid-19 around you? | ||||

| Yes | 136 | 73.5 | ||

| No | 49 | 26.5 | ||

| COVID-19 symptoms | ||||

| Yes | 28 | 15.1 | ||

| No | 157 | 84.9 | ||

Healthcare professionals’ sexual desire (p = 0.003), weekly sexual intercourse frequency (p < 0.001), foreplay time (p < 0.001), sexual intercourse time (p < 0.001) decreased compared to the before the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, participants preferred less foreplay (p < 0.001), less oral sex (p < 0.001) and anal sex (p: 0.007) during the COVID-19 outbreak, and more non-face to face sexual intercourse positions (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of participants’ sexual attitudes before and during COVID-19.

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual desire level | 3.49 ± 1.12 | 3.22 ± 1.17 | 0.003a |

| Sexual intercourse or masturbation/week | 2.53 ± 1.12 | 1.32 ± 1.27 | <0.001a |

| Foreplay | |||

| Yes | 171 | 125 | <0.001 |

| No | 14 | 60 | |

| Foreplay time (min) | 16.38 ± 12.35 | 12.02 ± 12.14 | <0.001a |

| Oral sex | |||

| Yes | 111 | 63 | <0.001Mc |

| No | 74 | 122 | |

| Anal sex | |||

| Yes | 19 | 8 | 0.007Mc |

| No | 166 | 177 | |

| Sexual intercourse time (min) | 24.65 ± 19.58 | 19.38 ± 18.85 | <0.001a |

| Positions (%) | |||

| Face to face | 54.51 | 45.49 | |

| Not face to face | 42.34 | 57.66 | <0.001Mc |

| Contraception | |||

| Yes | 110 | 90 | <0.006Mc |

| No | 75 | 95 | |

| Contraception method | |||

| Calender method | 3 | 0 | <0.001A |

| Coitus interruptus (withdrawal) | 29 | 26 | |

| Male/female condom | 39 | 62 | |

| Contraceptive pills | 21 | 18 | |

| Intra uterine device | 10 | 9 | |

| Tubal ligation | 3 | 3 | |

| Other | 5 | 4 | |

Mc Mc Nemar test, A ANOVA.

aDependent t-test.

Prevention methods were less preferred than before the COVID-19 outbreak, and condom protection was used more during the outbreak. (p < 0.001).

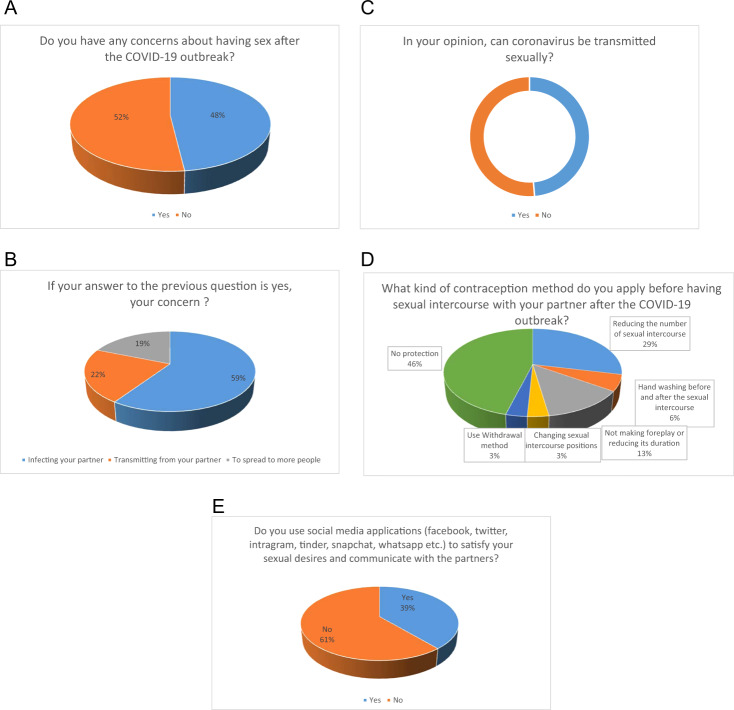

The percentage of participants concerned about sex due to the COVID-19 outbreak was 47.8%. (Fig. 1A). When asked about the reason for these concerns, 59.4% of the participants were concerned about infecting their partner. While 21.9% of the participants were worried about getting this virus from their partner, 18.7% are worried about the virus being transmitted to more people (Fig. 1B). About half (90/185) of the respondents answered yes to the question “Do you think Coronavirus can be transmitted sexually?” (Fig. 1C). In order to protect against COVID-19 transmission by sexual intercourse, it is preferred to decrease the amount of sexual intercourse (28.6%) and not to have foreplay or preferred to shorten the duration of foreplay (13%) (Fig. 1D). During this pandemic, 38.9% of the participants (72/185) reported that they used social media applications (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tinder, Snapchat, WhatsApp etc.) to satisfy their sexual desires and communicate with the opposite sex (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1. Participants’ sexual attitudes towards COVID-19.

a Concerns about COVID-19. b Cause of Concern. c Do you think can coronavirus be transmitted sexually? d Protection contraception method of Healthcare workers on sexual intercourse. e Social media usage during COVID-19 for sexual satisfaction.

The mean scores of the male and female sexual function subdomains are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mean IIEF, FSFI, STAI-I, STAI-II and BECK scores of the participants.

| Mean ± SD | Min–Max | |

|---|---|---|

| IIEF-EF | 21.65 ± 9.00 | 0–30 |

| IIEF-OF | 7.46 ± 3.56 | 0–10 |

| IIEF-SD | 6.92 ± 2.32 | 0–10 |

| IIEF-IS | 8.51 ± 5.30 | 0–14 |

| IIEF-OS | 6.19 ± 2.98 | 0–10 |

| FSFI-desire | 3.75 ± 1.46 | 1–6 |

| FSFI-arousal | 2.92 ± 2.21 | 0–6 |

| FSFI-lubrication | 3.16 ± 2.33 | 0–6 |

| FSFI-orgasm | 3.19 ± 2.25 | 0–6 |

| FSFI-satisfaction | 2.93 ± 2.37 | 0–6 |

| FSFI-pain | 3.21 ± 2.64 | 0–6 |

| FSFI-total | 19.13 ± 11.42 | 1–35 |

| STAI-I | 44.61 ± 11.74 | 20–80 |

| STAI-II | 42.01 ± 8.66 | 23–62 |

| BECK | 11.49 ± 7.82 | 0–34 |

IIEF International Index of Erectile Function, EF Erectile Function, OF Orgasmic Function, SD Sexual Desire, IS Intercourse satisfaction, OS Overall Satisfaction, FSFI Female Sexual Function Index, STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

A total of 41 participants had sexual dysfunction (cutoff for sexual dysfunction in women: 26.55, male: 24). Sexual dysfunction was more common in men (p < 0.001) and alcohol users (p: 0.003). The anxiety score of the participants with sexual dysfunction was higher (p: 0.022) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison between participants with sexual dysfunction and normal controls.

| Normal sexual function (n = 144) | Sexual dysfunction (n = 41) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 58 | 38 | <0.001*Chi |

| Female | 86 | 3 | |

| Age group | |||

| 18–24 | 10 | 3 | 0.332A |

| 25–34 | 108 | 30 | |

| 35–44 | 18 | 8 | |

| 45–54 | 8 | 0 | |

| Department | |||

| COVID department | 38 | 10 | 0.533A |

| COVID outpatient clinic | 33 | 9 | |

| COVID emergency | 30 | 13 | |

| COVID ICU | 39 | 9 | |

| Other | 4 | 0 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 70 | 23 | 0.398Chi |

| Married | 74 | 18 | |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 1 | 0 | 0.137A |

| High school | 12 | 0 | |

| University | 131 | 41 | |

| Income level | |||

| Low | 3 | 1 | 0.230A |

| Average | 31 | 4 | |

| High | 109 | 36 | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Yes | 57 | 13 | 0.233Chi |

| No | 87 | 28 | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Yes | 58 | 27 | 0.003*Chi |

| No | 86 | 14 | |

| Chronic disease | |||

| 0 | 113 | 37 | 0.065Chi |

| ≥1 | 31 | 4 | |

| STAI-I | 44.06 ± 10.92 | 46.56 ± 14.23 | 0.022*t |

| STAI-II | 42.35 ± 8.53 | 40.80 ± 9.11 | 0.313t |

| BECK | 11.40 ± 7.62 | 11.80 ± 8.59 | 0.775t |

t Independent t-test, chi Chi square test, A ANOVA.

*p < 0.05.

When factors affecting sexual dysfunction were analyzed as univariate and multivariate, sexual dysfunction was shown to be significantly more common in male sex (OR: 0.053) and alcohol users (OR: 2.925) (Table 5).

Table-5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p | CI | OR | p | CI | |

| Gender | 0.056 | <0.001 | 0.016–0.201 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 0.015–0.181 |

| Age | 1.014 | 0.717 | 0.941–1.093 | |||

| Chronic disease | 1.318 | 0.676 | 0.361–4.820 | |||

| Smoking | 1.463 | 0.395 | 0.609–3.515 | |||

| Alcohol | 2.818 | 0.016 | 1.214–6.544 | 2.925 | 0.009 | 1.309–6.538 |

| COVID-19(+) | 0.326 | 0.366 | 0.029–3.704 | |||

| Close Contact with COVID-19(+) person | 0.480 | 0.696 | 0.280–2.007 | |||

Discussion

In this survey study involving healthcare professionals struggling with the COVID-19 outbreak in pandemic hospitals, the participants’ sexual desire decreased, their foreplay and sexual intercourse frequency decreased and their sexual intercourse positions changed during the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, it was found that male participants, alcohol users and participants with higher anxiety scores had more sexual dysfunction.

Due to the rapid spread of the COVID-19 outbreak worldwide, patients with sexual health problems cannot apply to the hospitals [20]. With the progression of the pandemic, studies showing that sexual life has changed have been published [21, 22]. In this period, it is recommended that healthcare professionals who are interested in sexual health use different methods to find solutions to patients’ problems rather than face to face [23]. The foremost methods is telemedicine. Patients can communicate with the physician via audio or video calls without the need to come to the hospital.

The rate of spread of the COVID-19 outbreak appears to be quite high and causes severe stress for healthcare professionals working in the front line. A study on the psychological effects of the outbreak of the SARS virus, which is a member of the coronavirus family, in 2003, showed that the social and mental health of healthcare workers worsened after caring for SARS patients [24]. A recent study on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on health workers has found that health workers show symptoms of 29.8% stress, 24.1% anxiety, and 13.5% depression [25]. It has been observed that the effects of this outbreak, which affects the world, on the psychology of healthcare workers have an effect on their sexual lives [8]. The anxiety scores of the participants who had sexual dysfunction were significantly higher. In addition, although no significant difference was found with the depression scale scores, the depression scores were higher in the group with sexual dysfunction. We believe that this situation may contribute to the spread of the virus of healthcare workers and a decrease in their sexual desire due to this anxiety.

The primary mode of transmission of SARS CoV-2 is from person to person with respiratory droplets and respiratory contact. There are two modes of spread—(1) Droplet transmission and (2) Airborne transmission [26]. It is not yet known whether SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted sexually. Although virus RNA has been detected in semen in a recently published study [27], it has not yet been shown to be transmitted by sexual intercourse. However, due to the nature of sex, the possibility of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 may be high due to the close contact of the partners and the possibility of droplets passing into the respiratory tract during sexual intercourse and foreplay. The lack of clarity of this situation is also observed in healthcare professionals. In our study, almost half of healthcare workers stated that it could be transmitted by sexual intercourse and they were concerned about this issue. In addition, oral sex and anal sex preferences decreased during the COVID-19 outbreak. Previously, SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to be positive in rectal and anal swab samples [28, 29]. The possibility of contamination between body fluids has been effective in participants’ oral and anal sex preferences.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, participants preferred male condom use more to prevent transmission during possible sexual intercourse (p < 0.001). As a barrier that prevents vaginal fluid and semen from infecting the body, male condoms, an easy-to-apply and inexpensive method, has been preferred by the vast majority of participants considering contraception.

Appropriate hygiene methods include hand hygiene to reduce the risk of contamination from the infected person, relatives and healthcare workers [30]. Providing hand hygiene with alcohol or povidone iodine has been reported to be more effective against enveloped corona viruses compared to other antiseptic agents [31]. The vast majority of participants apply shortened foreplay and sexual intercourse and/or reduced sexual intercourse as a method of protection. In addition, the caution of hand hygiene before and after the relations is considered as another protection method.

Recently, the New York City Health Department issued guidance for its residents on safe sex practices during the COVID-19 outbreak [32]. In this guide, it was suggested to reduce the number of partners, to reduce or not to have foreplay, to provide hand hygiene before and after sexual intercourse and to use male condoms as a method of protection for a safe sexual intercourse. In the results of our study, it was observed that the healthcare professionals, who have the most contact with the virus and have the most information in the COVID-19 outbreak, comply with these protection methods.

Another interesting result was that it was determined that the majority of the participants with sexual dysfunction were male, used alcohol and had higher anxiety scores. People can use alcohol and other substances to deal with sexual performance anxiety, improve sexual performance, or overcome sexual dysfunction [33]. However, with prolonged use, alcohol use negatively affects sexual function and can lead to the development of sexual disorders. [34, 35]. Alcohol consumption can cause oxidative damage by increasing the production of toxic free radicals or reducing antioxidant levels [36].

The study has some limitations. The first is that the sexual functions of the participants before the COVID-19 outbreak and their anxiety and depression were not evaluated with validated questionnaires. In addition, the lack of questions for LGBT individuals is another limitation of the study. The response rate may be low due to the survey being answered online. Another limitation is that the date range of the study is when the pace of the epidemic begins to slow down. The time spent in the hospital and whether the relatives of the healthcare workers had COVID-19 were not questioned. Recall bias is another limitation of the study. This study is a preliminary study evaluating the sexual attitude of healthcare professionals. This study will shed light on conducting similar studies in more detail in healthcare workers and populations with similar risk groups (for example: teachers, bank employees, supermarket employees, etc).

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 outbreak, healthcare workers’ sexual desires decreased, the number of sexual intercourses decreased, their foreplay times decreased, and their sexual intercourse positions changed to less face to face. While men face more sexual dysfunction, alcohol use and anxiety are seen as an independent risk factor in the development of sexual dysfunction. In order to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2, it is necessary to reduce the frequency of sexual intercourse, shorten the foreplay time and pay attention to hand cleaning before/after intercourse. Future studies are needed to adapt and compare the results obtained from the sexual life attitudes of healthcare professionals who are most in contact with the virus.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. Jama. 2020;323:1239–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 4.Dunn M, Sheehan M, Hordern J, Turnham HL, Wilkinson D. ‘Your country needs you’: the ethics of allocating staff to high-risk clinical roles in the management of patients with COVID-19. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:436–40. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinzerling A, Stuckey MJ, Scheuer T, Xu K, Perkins KM, Resseger H, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 to Health Care Personnel During Exposures to a Hospitalized Patient - Solano County, California, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:472–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paoli D, Pallotti F, Colangelo S, Basilico F, Mazzuti L, Turriziani O, et al. Study of SARS-CoV-2 in semen and urine samples of a volunteer with positive naso-pharyngeal swab. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43:1819–22. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dost B, Koksal E, Terzi O, Bilgin S, Ustun YB, Arslan HN. Attitudes of Anesthesiology Specialists and Residents toward Patients Infected with the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19): A National Survey Study. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2020;21:350–6. doi: 10.1089/sur.2020.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, Ni X, Deng X, Jia Y, et al. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms of Health Care Workers during the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27:384–95. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30.. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Mishra A, Osterloh IH. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 1999;54:346–51.. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akkus E, Kadioglu A, Esen A, Doran S, Ergen A, Anafarta K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction in Turkey: a population-based study. Eur Urol. 2002;41:298–304. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aygin D, Aslan F. The Turkish adaptation of the Female Sexual Function Index. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2005;25:393–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spielberger CDGR, Luschene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Invenntory. California: ConsultingPsychologists Press; 1970.

- 17.Öner NLCA. Durumluk – Sürekli Kaygı Envanteri El Kitabı. Istanbul: İstanbul Bogaziçi Üniversitesi Yayınları, No:233; 1985.

- 18.Hisli N. Beck Depresyon Envanterinin üniversite öğrencileri için geçerliği, güvenirliği. Psikol Derg. 1989;7:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol. 1984;40:1365–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::AID-JCLP2270400615>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rizzo M, Liguori G, Verze P, Palumbo F, Cai T, Palmieri A. How the andrological sector suffered from the dramatic Covid 19 outbreak in Italy: supportive initiatives of the Italian Association of Andrology (SIA) Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:547–8. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-0288-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cocci A, Giunti D, Tonioni C, Cacciamani G, Tellini R, Polloni G, et al. Love at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic: preliminary results of an online survey conducted during the quarantine in Italy. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:556–7. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacob L, Smith L, Butler L, Barnett Y, Grabovac I, McDermott D, et al. COVID-19 social distancing and sexual activity in a sample of the British Public. J Sex Med. 2020.

- 23.Cocci A, Presicce F, Russo GI, Cacciamani G, Cimino S, Minervini A. How sexual medicine is facing the outbreak of COVID-19: experience of Italian urological community and future perspectives. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:480–2. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-0270-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen NH, Wang PC, Hsieh MJ, Huang CC, Kao KC, Chen YH, et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome care on the general health status of healthcare workers in taiwan. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:75–9. doi: 10.1086/508824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar M, Taki K, Gahlot R, Sharma A, Dhangar K. A chronicle of SARS-CoV-2: Part-I - Epidemiology, diagnosis, prognosis, transmission and treatment. Sci Total Environ. 2020;734:139278. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li D, Jin M, Bao P, Zhao W, Zhang S. Clinical Characteristics and Results of Semen Tests Among Men With Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208292. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kipkorir V, Cheruiyot I, Ngure B, Misiani M, Munguti J. Prolonged SARS-Cov-2 RNA Detection in Anal/Rectal Swabs and Stool Specimens in COVID-19 Patients After Negative Conversion in Nasopharyngeal RT-PCR Test. J Med Virol. 2020. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Wu Y, Guo C, Tang L, Hong Z, Zhou J, Dong X, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:434–5. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldust M, Abdelmaksoud A, Navarini AA. Hand disinfection in the combat against Covid-19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Rabenau HF, Kampf G, Cinatl J, Doerr HW. Efficacy of various disinfectants against SARS coronavirus. J Hosp Infect. 2005;61:107–11.. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sex and COVID-19 Fact Sheet The NYC Health Department 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-sex-guidance.pdf.

- 33.Grover S, Mattoo SK, Pendharkar S, Kandappan V. Sexual dysfunction in patients with alcohol and opioid dependence. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36:355–65.. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.140699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peugh J, Belenko S. Alcohol, drugs and sexual function: a review. J Psychoact Drugs. 2001;33:223–32.. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10400569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang XM, Bai YJ, Yang YB, Li JH, Tang Y, Han P. Alcohol intake and risk of erectile dysfunction: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Impot Res. 2018;30:342–51.. doi: 10.1038/s41443-018-0022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams ML, Nock B, Truong R, Cicero TJ. Nitric oxide control of steroidogenesis: endocrine effects of NG-nitro-L-arginine and comparisons to alcohol. Life Sci. 1992;50:Pl35–40. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]