Abstract

A downward trend in opioid prescribing between 2011 and 2018 has brought per-capita opioid prescriptions below the levels of 2006, the earliest year for which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published data. That trend has affected roughly ten million patients who previously received long-term opioid therapy. Any effort to reduce or replace a prior health practice is termed de-implementation. We suggest that the evaluation of opioid prescribing de-implementation has been misdirected, within US policy and health research, resulting in detrimental impacts on patients, their families and clinicians. Policymakers and implementation scientists can address these deficiencies in how we study and how we perform opioid de-implementation by applying an implementation science framework: the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. The Consolidated Framework lays out relevant domains of activity (internal, external, etc.) that influence implementation processes and outcomes. It can deepen our understanding of how policies are chosen, communicated, and carried out. Policymakers and researchers who embrace this framework will need a better approach to measuring success and failure in health care where both pain and opioids are concerned. This would involve shifting from a reductive focus on opioid prescription counts toward measures that are more effective, holistic, and patient-centered.

A downward trend in opioid prescribing has emerged in the wake of a crisis of overdose and addiction related to opioids, coupled with a recognition that the benefits of opioids had been oversold.1 According to 2019 data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), opioid prescribing has declined 37% since its peak in 2011, while prescriptions exceeding 90 morphine milligram equivalents fell by 67% since 2008.2 This decline accelerated after a 2016 Guideline was issued.3 Such efforts, however, can have unintended consequences.4 By 2019, there was widespread recognition that reductions in prescribing had not been implemented in ways that consistently protected patients.5–9 Patients, media, government agencies, and professional literature acknowledged instances of worsening pain, loss of access to care, and death by suicide,7,10–13 even as others described successes in patient-centered voluntary dose reduction14 and post-operative pain management.15

By 2019, the CDC avowed that its guidance had been misapplied.16,17 Just as opioid prescribing once had rocketed ahead of the supporting science, opioid deprescribing was often mandated and carried out in ways that lacked evidentiary support.6,7,18,19 But this failure raises urgent questions for agencies seeking to implement changes to care and for researchers who partner with them: how can well-intended changes to care sometimes transpire in ways that are unsafe or harmful? Studies that measure the rise and fall of prescriptions rarely portray how such opioid prescribing changes are carried out.20 So how should these changes to care be measured, particularly if patient harm may be taking place amidst efforts to change care that are intended to be beneficial?21

Implementation science provides a framework to explain how organizational efforts to change care may play out poorly in practice and can improve efforts to measure such change.22–24 In this perspective, we describe how a well-regarded framework for understanding implementation of health system change can guide needed changes and ensure that research can assess their success or failure for the 10 million Americans who receive opioids long term.25

CONSIDERATIONS TO GUIDE FUTURE IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE ON PRESCRIPTION OPIOID REDUCTION

Research on changing opioid prescriptions has emphasized number of pills prescribed,26 or the number of long- versus short-term prescriptions,27 with weaker focus on outcomes for patients, or on how health care organizations reduce or eliminate opioid prescribing for long-term recipients. De-implementation has been defined as reducing or stopping services or practices that are ineffective, unproven, harmful, overused, or inappropriate.4 In relation to prescription opioids, de-implementation can mean dose reductions, stoppage, or a decision not to initiate. In proposing how better to study this process, one stipulation is offered. The interest in reducing opioid reliance does not represent, for us, a commitment to eliminating opioids from pain care.28 Rather, if de-implementation occurs, it must be undertaken with care,4,29 so as to alleviate adverse outcomes7,12,13,30 and avoid exacerbating health care inequities.31 The following section will show how the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) can help us carry out, evaluate, and study those changes in a way that includes patients.32

CONSOLIDATED FRAMEWORK FOR IMPLEMENTATION RESEARCH

Implementation researchers ask how and why efforts to change health care delivery succeed or fail. It is not enough to ask whether prescriptions have declined, but how reductions were made to happen and what the impact was on patients with pain. The CFIR groups relevant constructs into five domains.32 Each domain can shed light on shortfalls in current opioid reduction efforts and point to contextual factors that influence whether de-implementation is done well or poorly. For these reasons, metrics serve as the focal point for recommendations to improve research in the future.

Characteristics of Individuals

This domain is linked to all others, as the prescriber and collaborating clinical personnel are central actors in any deprescribing process. This domain includes professionals’ knowledge and competence with pain, opioids, and related topics, along with the condition of their therapeutic relationship. It includes their comfort with difficult interactions. Clinicians’ longstanding distrust of patients with pain or opioid receipt,33,34 and their discomfort with uncertainty,35 may pose challenges. One study found primary care providers often are not motivated to treat chronic pain or opioid use disorder.36 Finally, the prescriber’s ability to handle external pressures matters. Such pressures may include fear of losing a license, being investigated, being physically attacked, or being censured. Training initiatives address knowledge,37 but rarely address provider capacity to handle external pressures or to achieve clinical engagement and boundary clarity.38 Future de-implementation efforts should evaluate provider characteristics, such as knowledge and competence related to taper and pain care, confidence and ability to navigate challenging professional pressures, and how these factors influence de-implementation and patient outcomes.

Characteristics of the Intervention

To study the effects of local, regional, or national prescribing policies, researchers must document specific steps taken to alter care. They must characterize the flexibility of the policy (or alternatively, its inflexibility). What letters, orders, policies, resources, supports, or other actions were used to change pain care and opioid prescribing? What did clinicians perceive to be the consequences of deviating from new policies? Health system payers and administrators often are the ones who decide whether de-implementation of some practices will be coupled to implementation of others,39 such as new pain care modalities.40,41 They decide whether prescription reduction policies are unilaterally mandated, or permit individualization. Given the lack of evidence on across-the-board opioid reduction outcomes, we favor strategies that attend to the unique needs of the individual patient. Whether individualization is permitted, however, is rarely reported.20,42–45 Evaluation of de-implementation efforts should ask whether proposed alternatives to opioids are appropriate for the patient, provider, and setting.29 Such research should include record review, surveys, interviews, and organizational assessments to capture these matters.

Inner Setting

Inner setting includes organizational culture and actions taken by leaders including commitment and alignment of effort.46 Their actions may include offers of tangible support, or the use of threats or reward to accelerate changes, or to pre-empt expressions of concern from staff. Care transformation efforts falter if perceptions of professional risk constrain communication about risk to patients.47 The CFIR defines “learning climate” to include psychological safety: the degree to which “leaders express their fallibility and need for team members’ assistance and input.” Such issues echo across industries and they are measurable.48,49

Process

The implementation process includes multiple organizational factors, such as implementation plans, engagement of the team, resource allocation, results measurement across stakeholders, and how the process is revised in real time. Contemporary reports on opioid deprescribing often lack descriptions of process of change,20,21,43 or they reference a single element (e.g., a clinic policy)50 with prescription volume and dose treated as a proxy for both the intervention and the outcome. Such “pill dynamic” analyses typically fail to include measures of process or patient-centered outcomes, and they fail to measure the experience of the prescriber.20,43,51 As a result, they tend to reinforce a reductive focus on opioid dose reduction, alone.

Outer Setting

Outer setting is key to understanding why opioid prescribing reductions unfolded in problematic ways in the USA.6,7,13,52 Outer setting has several components, but we focus on two.

The first domain involves the extent to which the implementation (or de-implementation) program reflects the needs of the patient group and the barriers to meeting such needs. It is axiomatic that patient needs should be the first consideration in care delivery, and yet programmatic efforts to address pain may falter in this regard. Patients with severe pain often have multiple serious comorbidities53 and logistic barriers that may stymie receipt of care.54 The complexity of the patient and their health care needs is insufficiently addressed in national opioid prescribing guidance.55–57 When opioid reduction is considered, one published tapering protocol stresses the need for patient-centeredness, including in the outer setting: “the focus should never be solely on opioid reduction. The biopsychosocial model of pain treatment should be applied to facilitate not only goals for pain and opioid reduction but improved function and quality of life.”58

The second aspect of the outer setting involves external policies. For instance, national quality metrics have caused problematic forms of de-implementation rife with unintended consequences. External policies, including metrics, reflect public concern, which has taken count of the role played by prescriptions in the overdose crisis.59,60 That concern is embodied by high-stakes litigation,61 state and federal laws, novel regulations,62 media coverage,63 research, and payer policies. One quality metric treats the number of patients at high dose (initially, 120 MME, later revised downward to 90 MME) as reflecting poor care. That metric was proposed by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance,64 then embraced by the National Committee for Quality Assurance65 and others.66 In the CDC’s Guideline, the 90 MME threshold was couched as cautionary (“should avoid increasing dosage to ≥90 MME/day or carefully justify a decision to titrate dosage to ≥90 MME/day”), and the CDC did not require or insist on dose reduction for patients above such doses.57 While invoking the CDC’s authority, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General simplified 90 MME as a dose “to avoid” in a report declaring its partnership with law enforcement. That threshold is now used to profile federal agency performance,67 to allocate bonus payments under the Medicare 5-Star Program,68 to initiate criminal investigations,69 and for pharmacy benefits decisions. The original distinction between doses forced down, versus doses not escalated, has no presence in these metrics used by law enforcement, quality arbiters, or payers. This situation induces fear among clinicians. In interviews conducted by our team, one clinician stated: “Government involvement in this issue really does not help in terms of regulation, it makes people paranoid about treating patients.”70

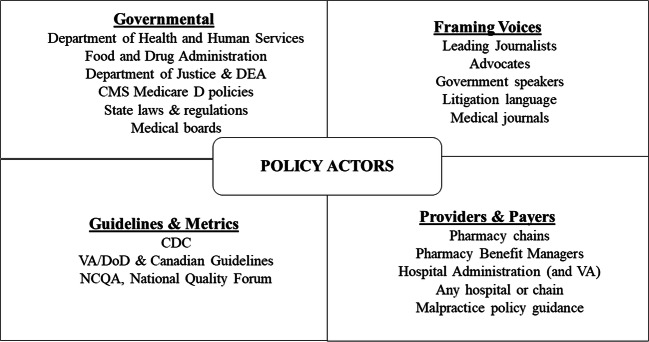

Contemporary scholarship on policy helps to explain why implementation of the CDC’s Guideline has often contradicted both the language and the spirit of the Guideline itself.7,71 First, policy scholars note that the aspiration for completely rational policies is almost never upheld in real-world responses to complex problems (this is termed “bounded rationality”71). Decision-makers lack the time to absorb the problems they are called upon to solve, or power to fully solve them. Thus, they are drawn to reductive solutions, targeting the most accessible point of leverage, based on which advocates they listen to. Second, policy is not shaped by one party, but by many at once. We illustrate the diversity of opioid prescription policy vectors in Figure 1, broken crudely into categories of “Governmental,” “Guidelines and Metrics,” “Providers and Payers,” and “Framing Voices,” even though there is overlap among these compartments. Very few studies formally assess how these parties interact and the resultant effects on care.72

Fig. 1.

The figure offers selected examples of actors and agencies that, collectively, influence opioid prescribing in the USA, grouped into the following domains: “Governmental,” “Guidelines and Metrics,” “Framing Voices,” and “Providers and Payers.” The four domains are offered with illustrative intent and are not necessarily exhaustive or mutually exclusive. For example, a government agency may produce a guideline and also influence how the guideline is understood through collaboration with a journalist (i.e., a Framing Voice). CMS, The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DEA, Drug Enforcement Agency; VA, Department of Veteran Affair’s; DoD, Department of Defense; NCQA, National Committee for Quality Assurance.

A WAY FORWARD

The CFIR domains should be considered by leaders and researchers seeking to advance pain care. The domains expose the complexity of prescription opioid de-implementation and its impact on patients. Better metrics could help capture that impact. Table 1 offers examples. At the health system level, one measure deserving priority is the count of patients lost from clinics or health systems. Patients often feel forced to leave clinics when their doctors announce that prescription opioids will be reduced or stopped.73 One clinic reported losing 36% of its patients.73 Other proposed measures, including mortality, are offered in Table 1. They include patient-reported autonomy in taper, readiness to taper, satisfaction with behavioral treatments, and functional outcomes.58 While not exhaustive, that list can guide health systems and research partners to develop programs focused on best serving patients with pain, related vulnerabilities, and opioid receipt, and better stewardship for their care.

Table 1.

Enhanced Metrics for Success in Assessing Prescription Opioid de-implementation

| Metric | Justification | Anticipated challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Systems-level metrics | ||

| Mortality after opioid dose change1 | Mortality increase after opioid stoppage seen in some reports | Specific causal attributions subject to debate |

| Hospitalization within 3 months of opioid dose change1 | Emergent hospital use seen in some studies | Disentangling contributors to hospitalization may be difficult |

| Number of patients accessing alternative pain care1 | De-implementation of opioids requires a plausible pain care alternative | Denominator of persons needing care may be difficult to calculate |

| Number of patients accessing mental health services when there is a coexisting mental health diagnosis1 | Mental symptoms influence pain experience | Not all mental health conditions require professional treatment |

| Number of patients leaving health system after opioid stoppage1 | Termination of care relationships noted in some reports | Re-engagement after termination of care has not been studied |

| Patient-level metrics | ||

| Appropriateness of dose3 | The CDC Guideline calls for documenting calibration of risk and benefit based on patient function | Divergent views on opioids’ utility in chronic pain |

| Pain expectations2 | Patient expectations influence care experience and retention | Patient expectations vary over time |

| Opioid dose expectations | Expectations regarding opioid prescribing are distinct from expectations about pain | Patient expectations vary over time |

| Taper autonomy, as perceived by patient | Perceptions of losing control in care may be traumatic | Not all patients require or expect full autonomy in medication choice |

| Satisfaction with behavioral treatments | Patient engagement and retention depend on satisfaction with treatment | Satisfaction may not indicate quality of the treatment |

| Use of other illicit drugs or alcohol in context of opioid prescription change | Transition to non-prescribed substance may confer additional risk | Self-report and laboratory indicators have varying levels of accuracy over time |

CONCLUSIONS

When a multi-faceted, complex health issue becomes a public health crisis, the desire to “solve” or “mitigate” takes hold with a momentum of its own. A crisis deserves no less. However, nationally adopted quality metrics have convinced some patients with pain that their survival and functioning are no longer concerns for the systems in which they receive care. This outcome is unacceptable.

Health systems must measure outcomes of their de-implementation efforts to ensure that their actions are advancing patient health. Implementation science points toward a reappraisal of how our health system responses to the opioid crisis can become more effective, holistic, and patient-centered.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Kertesz affirms past personal ownership of stock in Merck and Abbott pharmaceutical companies, sold in December of 2017, and not exceeding 5% of his assets at the time. Dr. Kertesz holds stock in CVS Caremark, Thermo Fisher, and Zimmer Biomet, not exceeding 5% of his assets. Dr. Kertesz reports his spouse holds equity in Merck, Abbot, Thermo Fisher, and Johnson and Johnson, in her private assets, not exceeding 10% of her assets. Dr. Kertesz receives income from UpToDate, Inc. Dr. Darnall is the recipient of a research award from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (#1610-3700), author royalties from multiple books, and compensation as chief scientific advisor at AppliedVR. Dr. Varley receives part-time income from Heart Rhythm Clinical and Research Solutions.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not represent positions or views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. All statements in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Frieden TR, Houry D. Reducing the risks of relief--the CDC Opioid-Prescribing Guideline. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1501–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1515917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2019 Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes — United States Surveillance Special Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Published November 1, 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2019-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2020.

- 3.Bohnert ASB, Guy GP, Jr, Losby JL. Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 Opioid Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(6):367–375. doi: 10.7326/M18-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin R. Limits on opioid prescribing leave patients with chronic pain vulnerable. JAMA. 2019;321(21):2059–2062. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroenke K, Alford DP, Argoff C, et al. Challenges with implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Opioid Guideline: a consensus panel report. Pain Med. 2019;20(4):724–735. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R. No Shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2285–2287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1904190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szalavitz M. When the cure is worse than the disease. New York Times. February 9, 2019, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/09/opinion/sunday/painopioids.html. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 9.Hoffmann J, Goodnough A. Good news: opioid prescribing fell. The bad? Pain patients suffer, doctors say. New York Times. March 6, 2019, 2019. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/06/health/opioids-pain-cdc-guidelines.html. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 10.Kertesz SG, Satel SL, Gordon AJ. Opioid Prescription Control: When The Corrective Goes Too Far. Health Affairs Blog. January 19, 2018. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180117.832392/full/. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 11.Llorente EAs doctors taper or end opioid prescriptions, many patients driven to despair, suicide. December 10, 2018. FoxNews. Available at: https://www.foxnews.com/health/as-opioids-become-taboo-doctors-taper-down-or-abandon-pain-patients-driving-many-to-suicide Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 12.Human Rights Watch. “Not Allowed to Be Compassionate”: Chronic Pain, the Overdose Crisis, and Unintended Harms in the US. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/hhr1218_web.pdf. AccessedSeptember 30, 2020.

- 13.United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA identifies harm reported from sudden discontinuation of opioid pain medicines and requires label changes to guide prescribers on gradual, individualized tapering. April 17, 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-identifies-harm-reported-sudden-discontinuation-opioid-pain-medicines-and-requires-label-changes. Accessed September 30, 2020

- 14.Darnall BD, Ziadni MS, Stieg RL, Mackey IG, Kao MC, Flood P. Patient-centered prescription opioid tapering in community outpatients with chronic pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):707–708. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vu JV, Howard RA, Gunaseelan V, Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Englesbe MJ. Statewide implementation of postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(7):680–682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1905045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Appropriate Dosage Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-Term Opioid Analgesics. October 10, 2020. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020

- 17.State of Washington Department of Health. Available at: https://wmc.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/documents/Clarification-opioid-rules_9-20-2019.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020

- 18.Manhapra A, Arias AJ, Ballantyne JC. The conundrum of opioid tapering in long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a commentary. Substance Abuse. 2017;39(2):152-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Fenton JJ, Agnoli AL, Xing G, et al. Trends and rapidity of dose tapering among patients prescribed long-term opioid therapy, 2008-2017. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(11):e1916271. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadlandsmyth K, Mosher H, Vander Weg MW, Lund BC. Decline in prescription opioids attributable to decreases in long-term use: a retrospective study in the Veterans Health Administration 2010-2016. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2018;33(6):818–824. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4283-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611–612. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274–1281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(3):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mojtabai R. National trends in long-term use of prescription opioids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(5):526–534. doi: 10.1002/pds.4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hincapie-Castillo JM, Goodin A, Possinger M-C, Usmani SA, Vouri SM. Changes in opioid use after Florida’s restriction law for acute pain prescriptions. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(2):e200234–e200234. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowenstein M, Hossain E, Yang W, et al. Impact of a state opioid prescribing limit and electronic medical record alert on opioid prescriptions: a difference-in-differences analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2020;35(3):662–671. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05302-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnett ML. Opioid prescribing in the midst of crisis - myths and realities. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1086–1088. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1914257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prusaczyk B, Swindle T, Curran G. Defining and conceptualizing outcomes for de-implementation: key distinctions from implementation outcomes. Implementation Science Communications. 2020;1:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Mark T, Parish W. Opioid medication discontinuation and risk of adverse opioid-related health care events. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2019: 103:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Helfrich CD, Hartmann CW, Parikh TJ, Au DH. Promoting health equity through de-implementation research. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(Suppl 1):93–96. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.S1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, Marlatt GA, Bradley KA. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(5):327–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, et al. The patient–provider relationship in chronic pain care: providers’ perspectives. Pain Medicine. 2010;11(11):1688–1697. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iannello P, Mottini A, Tirelli S, Riva S, Antonietti A. Ambiguity and uncertainty tolerance, need for cognition, and their association with stress. A study among Italian practicing physicians. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1270009. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2016.1270009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varley AL, Lappan S, Jackson J, et al. Understanding barriers and facilitators to the uptake of best practices for the treatment of co-occurring chronic pain and opioid use disorder. J Dual Diagn. 2020;16(2):239–249. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2019.1675920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiner SJ. On Becoming a Healer: the Journey from Patient Care to Caring About Your Patients. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2020.

- 39.Wang V, Maciejewski ML, Helfrich CD, Weiner BJ. Working smarter not harder: coupling implementation to de-implementation. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(2):104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeBar L, Benes L, Bonifay A, et al. Interdisciplinary team-based care for patients with chronic pain on long-term opioid treatment in primary care (PPACT) - Protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;67:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carey EP, Nolan C, Kerns RD, Ho PM, Frank JW. Association between facility-level utilization of non-pharmacologic chronic pain treatment and subsequent initiation of long-term opioid therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(Suppl 1):38-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Cigna. Cigna’s Partnership with Physicians Successfully Reduces Opioid Use by 25 Percent — One Year Ahead of Goal. Bloomfield, CT March 28, 2018. Available at: https://www.cigna.com/newsroom/news-releases/2018/cignas-partnership-with-physicians-successfully-reduces-opioid-use-by-25-percent-one-year-ahead-of-goal. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 43.Yenerall J, McPheeters M. The effect of an opioid prescription days’ supply limit on patients receiving long-term opioid treatment. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;77:102662. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin LA, Peltzman T, McCarthy JF, Oliva EM, Trafton JA, Bohnert ASB. Changing trends in opioid overdose deaths and prescription opioid receipt among Veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(1):106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaughn IA, Beyth R, Ayers ML, et al. Multispecialty opioid risk reduction program targeting chronic pain and addiction management in Veterans. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):406–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Deusen LC, Holmes SK, Cohen AB, et al. Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32(4):309–320. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000296785.29718.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawton R, Parker D. Barriers to incident reporting in a healthcare system. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2002;11(1):15. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1999;44(2):350–383. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valentine MA, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Measuring teamwork in health care settings: a review of survey instruments. Med Care. 2015;53(4):e16–30. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827feef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weimer MB, Hartung DM, Ahmed S, Nicolaidis C. A chronic opioid therapy dose reduction policy in primary care. Subst Abus. 2016;37(1):141–147. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1129526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Porter SB, Glasgow AE, Yao X, Habermann EB. Association of Florida House Bill 21 with postoperative opioid prescribing for acute pain at a single institution. JAMA Surg. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Darnall BD, Juurlink D, Kerns RD, et al. International stakeholder community of pain experts and leaders call for an urgent action on forced opioid tapering. Pain Med. 2019;20(3):429–433. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pitcher MH, Von Korff M, Bushnell MC, Porter L. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the United States. The Journal of Pain. 2019;20(2):146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becker WC, Dorflinger L, Edmond SN, Islam L, Heapy AA, Fraenkel L. Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Family Practice. 2017;18(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0608-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2017;189(18):E659–E666. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. 2017. Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/pain/cot/. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 57.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darnall BD, Mackey SC, Lorig K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain and chronic pain self-management within the context of voluntary patient-centered prescription opioid tapering: the EMPOWER study protocol. Pain Med. 2019;21(8):1523-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Christie C, Baker C, Cooper R, Kennedy PJ, Madras B, Bondi P. The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. 2017. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Final_Report_Draft_11-15-2017.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 60.Quinones S.Dreamland : the True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic. Paperback edition. ed. New York: Bloomsbury Press; 2016.

- 61.Gluck AR, Hall A, Curfman G. Civil litigation and the opioid epidemic: the role of courts in a national health crisis. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2018;46(2):351–366. doi: 10.1177/1073110518782945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Conference of State Legislatures. Prescribing Policies: States Confront Opioid Overdose Epidemic. 2019. Available at: https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/prescribing-policies-states-confront-opioidoverdose-epidemic.aspx. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 63.Lopez G. The opioid epidemic, explained. explained.Available at: https://www.vox.com/scienceand-health/2017/8/3/16079772/opioid-epidemic-drug-overdoses. Accessed September 18, 2020

- 64.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. PQA Opioid Core Measure Set. Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Alexandria, VA. May 10, 2017. Available at. https://myemail.constantcontact.com/Press-Release---PQA-Receives-NQF-Endorsement-of-Three-Performance-Measures-to-Address-Opioid-Misuse-Abuse.html?soid=1108959632030&aid=tfl6y6ucOGo. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 65.National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA Updates Quality Measures for HEDIS 2018. July 11, 2017. Available at: https://www.ncqa.org/news/ncqa-updatesquality-measures-for-hedis-2018/. Accessed: September 30, 2020.

- 66.National Quality Forum. NQF Statement on Endorsement of Opioid Patient Safety Measures. Washington DC. May 10, 2017. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/News_And_Resources/Press_Releases/2017/NQF_Statement_on_Endorsement_of_Opioid_Patient_Safety_Measures.aspx. Accessed:September 30, 2020.

- 67.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Inspector General. Opioids in Medicare Part D: Concerns about Extreme Use and Questionable Prescribing. Washington, DC. July 2017. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-17-00250.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 68.Kaiser Family Foundation. Issue Breff Reaching for the stars: quality ratings of Medicare Advantage plans, February 2011. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/8151.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 69.United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General. Concerns About Opioid Use in Medicare Part D in the Appalachian Region. Report OEI-02-18-00224. Washington, DC. April 2019. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-18-00224.pdf on June 10, 2020. 2019.

- 70.Varley AL, Lappan S, Jackson J, et al. Understanding barriers and facilitators to the uptake of best practices for the treatment of co-occurring chronic pain and opioid use disorder. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2019:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Cairney P. Understanding Public Policy : Theories and Issues. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012.

- 72.Allen P, Pilar M, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implementation Science. 2020;15(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01007-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sturgeon JA, Sullivan MD, Parker-Shames S, Tauben D, Coelho P. Outcomes in long-term opioid tapering and buprenorphine transition: a retrospective clinical data analysis. Pain Medicine. 2020. pnaa029. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]