Abstract

Background

Treating hypertension is important but physicians often do not intensify blood pressure (BP) treatment in the setting of pain.

Objective

To identify whether reporting pain is associated with (1) elevated BP at the same visit, (2) medication intensification, and (3) elevated BP at the subsequent visit.

Design

Retrospective cohort

Setting

Integrated health system

Participants

Adults seen in primary care

Exposure

Pain status based on numerical scale: mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), or severe (≥ 7).

Main Measures

We defined elevated BP as ≥ 140/80 mmHg and medication intensification as increasing the dose or adding a new antihypertensive medication. Multilevel regression models were used to find the association between pain and (1) elevated BP at the index visit; (2) medication intensification at the index visit; and (3) elevated BP at the subsequent visit. Models adjusted for demographics, chronic conditions, and clustering within physician. In the third model, we adjusted for initial systolic BP as well.

Key Results

Our population included 56,322 patients; 3155 (6%) reported mild pain, 5050 (9%) reported moderate pain, and 4647 (8%) reported severe pain at the index visit. Compared with no pain, the adjusted odds ratios of elevated BP were 1.38 (95% CI: 1.28–1.48) for severe pain, 1.06 (95% CI: 0.99–1.14) for moderate pain, and 1.02 (95% CI: 0.93–1.12) for mild pain. Adjusted odds ratios of medication intensification at the index visit were 0.65 (95% CI: 0.54–0.80) for mild pain, 0.61 (95% CI: 0.52–0.72) for moderate pain, and 0.55 (95% CI: 0.47–0.64) for severe pain. Among patients with elevated BP at the index visit, reporting pain at the index visit was not associated with elevated BP at the subsequent visit.

Conclusions

When patients reported pain, physicians were less likely to intensify antihypertensive treatment; nevertheless, patients reporting pain were not more likely to have elevated BP at the subsequent visit.

KEY WORDS: hypertension, quality of care, pain, medications, primary care

BACKGROUND

Pain and elevated blood pressure (BP) are both highly prevalent in the USA.1, 2 Since the nervous and cardiovascular systems interact within the human body, managing hypertension in the setting of pain may be challenging.3, 4 Acute pain causes a rise in BP, probably as a survival mechanism allowing humans to escape immediate harm.5 In experimental settings, normotensive individuals’ systolic BP increased up to 30 mmHg6, 7 while being subjected to an acute painful stimulus.8 This experimental evidence may underlie the widespread belief that pain can be responsible for elevated BP in the office setting.9 However, subjecting people to pain for longer duration (e.g., 60 min) produces heterogeneous results with some subjects having increased BP while others show a decrease.10 It is not known whether patients who report pain in primary care are more likely to have elevated BP.

Treating elevated systolic BP is important—for each 5 mmHg increase in the standard deviation of systolic BP, the pooled hazard ratio for stroke increased 17% and 27% for coronary heart disease.11 Yet, physician’s often fail to initiate or intensify BP treatment in the setting of elevated BP,12, 13 particularly if patients report pain.14 The implications of this finding are unclear. First, it is not known whether this delay is justified, since there are no large studies assessing the relationship between pain and BP in primary care practice. Second, it is not known whether such delays are harmful. While a short delay may be acceptable, a substantial delay can increase risk for adverse cardiovascular events, such as stroke.15 On the other hand, adding an antihypertensive medication when BP is spuriously elevated can cause side effects without providing benefit.16

To answer these questions and better inform decision-making regarding medication intensification in the presence of pain, we assessed the relationship between pain, BP, and treatment among primary care patients in a large, integrated health system. Our objective was to identify whether reporting pain was associated with either systolic BP or delayed medication intensification at the time of the visit. We also assessed whether reporting pain was associated with elevated BP at the subsequent visit. We hypothesized that pain would not be associated with elevated BP, but that reporting pain would be associated with delayed treatment and subsequent elevated BP.

METHODS

This retrospective cohort study included adult primary care patients seen in a large, integrated health system between January and December 2015. The study was approved by Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Review Board. Thirty-seven primary care practice sites, representing both urban and suburban locations, were included. At all primary care visits, patients have pain and BP assessed routinely, as described below. Data on patient pain and BP were collected from the electronic health record. We chose the patients’ first visit in 2015 with a BP reading and a pain score as their index visit. We excluded patients who did not have documented measures of both pain and BP at any visit in 2015. We also excluded patients with end-stage renal disease, or pregnancy. To identify the effect of delayed medication in 2015 on future BP readings, we also included systolic BP in the first half of 2016.

Measures

As part of routine care, medical assistants screened patients for pain using the question “Are you having pain associated with your visit today?” Patients who responded affirmatively were asked to rate the severity of the pain using a numerical rating pain scale, ranging from 0 to 10 with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the most intense pain possible. We categorized scores of 1–3 as mild, 4–6 as moderate, and ≥ 7 as severe pain.17

Blood pressure was measured by a medical assistant using an electronic BP cuff and the exact value was manually entered into the EHR (i.e., no rounding). If the BP was elevated, then a BpTRU machine (which takes six serial measurements) was used to identify the average BP. During the visit, the physician may decide to retake a patient’s BP either manually or electronically and document the reading in the EHR. In these rare cases, we used the physician’s BP reading, which serves as the reading of record. We defined elevated BP as a final reading ≥ 140/80 mmHg. We focused our analysis on systolic BP because it has a greater effect on myocardial infarction and stroke than diastolic BP.15 To identify patients’ subsequent systolic BP, we used the next BP measurement between 30 and 180 days after the index visit.

Medication Initiation or Intensification

Medication initiation or intensification was defined as a patient receiving prescription for a new antihypertensive medication or a higher dose of an existing medication within 1 day of the index visit.

Confounders

From the electronic health record, we collected demographic (age, sex, race, marital status, insurance) and chronic condition data. Race was categorized as White, Black or other. Insurance was categorized as private versus other. Chronic conditions were based on diagnoses recorded by the provider during any 2015 primary care visit. Diagnoses were based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code definitions from the Medicare Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse.18

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis included chi-square tests for categorical variables and Student’s t tests for continuous variables. We used a Kruskal–Wallis equality-of-populations rank test to identify the association between reported pain severity and prescription for an antihypertensive medication in the 180 days following the index date.

We used multilevel regressions to identify the association between reporting pain and (1) systolic BP at the index visit and (2) elevated BP at the index visit. We then restricted the analysis to patients who had elevated BP at the index visit to identify the association between reporting pain and medication intensification. We focused on patients with elevated BP because they are the most likely to need medication intensification. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, marriage, insurance status, number of chronic conditions and clustering within physician.

We used multilevel linear regression to identify the association between pain at the index visit and (1) days to the subsequent visit and (2) change in systolic BP at the subsequent visit. Multilevel logistic regressions were used to identify the odds of (1) medication initiation or intensification at the subsequent visit and (2) elevated BP at the subsequent visit. Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, marriage, insurance type, number of chronic conditions, initial systolic BP, and clustering within physician. We included initial systolic BP in the regression model because systolic BP at the index visit was both related to whether an individual received a medication at the index visit and the likelihood of individually having subsequently elevated BP. All four of these analyses were restricted to patients who had elevated BP at the index visit. Stata 14.0 was used for the analysis.

RESULTS

Our study population included 56,322 individuals who had at least one BP reading and a pain score on the same day. Patients had a median age of 62.4 (IQR: 52.0–71.5). The majority were women (59%, n = 33,483), White (81%, n = 45,463), and married (63%, n = 35,208). At the first visit, 6% (n = 3155) reported mild pain, 9% (n = 5050) reported moderate pain, and 8% (n = 4647) reported severe pain. Table 1 presents demographic characteristics by reported pain status. Patients who reported pain were younger and more likely to be female, non-White, and non-married than patients who did not report pain.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Characteristics by Pain Status

| No pain, N = 43,470 | Mild pain, N = 3155 | Moderate pain, N = 5050 | Severe pain, N = 4647 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 61.4 (14.0) | 59.4 (13.9) | 59.0 (14.2) | 58.9 (13.9) | < 0.01 |

| Female | 58% | 57% | 66% | 68% | < 0.01 |

| Race | < 0.01 | ||||

| White | 82% | 84% | 77% | 67% | |

| Black | 13% | 11% | 18% | 26% | |

| Other | 4% | 4% | 5% | 7% | |

| Married | 64% | 66% | 60% | 52% | < 0.01 |

| Mean number of visits within 180 days | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | < 0.01 |

| Mean number of chronic conditions | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | < 0.01 |

| Private insurance | 50% | 55% | 51% | 43% | < 0.01 |

| Elevated blood pressure at the index visit | 21% (n = 9279) | 21% (n = 663) | 22% (n = 1110) | 28% (n = 1286) | < 0.01 |

Blood Pressure at Index Visit

The average adjusted systolic BP for patients who reported mild or moderate pain was similar to patients who reported no pain, but patients who reported severe pain had slightly higher systolic BP than patients reporting no pain (128.9 mmHg versus 127.3 mmHg, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted Systolic Blood Pressure, Medication Intensification, and Days to the Subsequent Visit by Reported Pain Category at the Index Visit

| No pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Adjusted β | 95% CI | Adjusted β/OR | 95% CI | Adjusted β/OR | 95% CI | Adjusted β/OR | 95% CI | |

| Systolic blood pressure | |||||||||

| Index visit | |||||||||

| Total population | 56,231 | 127.3 mmHg | 126.9, 127.6 | 126.7 mmHg | 126.1, 127.3 | 127.2 mmHg | 126.7, 127.7 | 128.9 mmHg* | 128.4, 129.4 |

| Population with elevated blood pressure | 12,310 | 147.0 mmHg | 146.6, 147.4 | 146.3 mmHg | 145.3, 147.3 | 146.7 mmHg | 145.9, 147.5 | 147.8 mmHg† | 147.1, 148.5 |

| Subsequent visit | |||||||||

| Population with elevated blood pressure at the index visit | 9084 | 136.1 mmHg | 135.7, 136.5 | 134.4 mmHg† | 133.0, 135.7 | 135.7 mmHg | 134.6, 136.7 | 135.1 mmHg | 134.2, 136.1 |

| Medication intensification among patients with elevated blood pressure at the index visit | |||||||||

| Odds of medication intensification index visit | 12,310 | Reference group | 0.65* | 0.54, 0.80 | 0.61* | 0.52, 0.72 | 0.55* | 0.47, 0.64 | |

| Odds of medication intensification at 180 days | 12,310 | Reference group | 0.74* | 0.62, 0.88 | 0.78* | 0.68, 0.90 | 0.78* | 0.68, 0.88 | |

OR, odds ratio; β, beta

*< 0.01 compared with no pain

†p < 0.05 compared with no pain

All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, marriage, insurance status, number of chronic conditions, and within-physician clustering. For the models with the outcomes of systolic blood pressure at the subsequent visit and odds of elevated blood pressure at the subsequent visit, we also included the patient’s baseline systolic blood pressure recorded at the index visit. Adjusted betas were obtained using the margins command in Stata after running the adjusted regression model

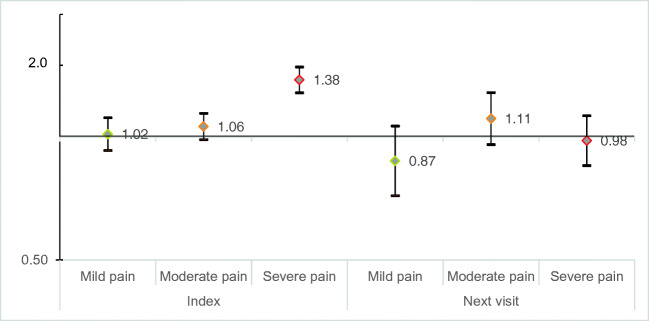

The percentage of patients who had elevated BP was also similar among patients who reported no pain (21%), mild pain (21%), or moderate pain (22%) but higher among patients who reported severe pain (28%, p < 0.01 for severe pain vs. no pain). The adjusted odds of elevated BP was higher for severe pain versus no pain (AOR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.28–1.48) but not for mild or moderate pain versus no pain (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratio of elevated systolic blood pressure versus non-elevated blood pressure at the index visit and subsequent visit by pain status. We used logistic regressions to find the association between report of pain at the index visit and odds of elevated blood pressure versus non-elevated blood pressure. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, marriage, insurance status, number of chronic conditions, and within-physician clustering. The model that evaluated odds of elevated blood pressure at the subsequent visit also included the patient’s baseline systolic blood pressure recorded at the index visit. At the index visit, when comparing mild pain to no pain the AOR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.93–1.12, p = 0.73; comparing moderate to no pain: AOR: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.99–1.14, p = 0.11; comparing severe pain to no pain: AOR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.28–1.48, p < 0.001. The sample size was 56,231. At the subsequent visit: comparing mild pain to no pain: AOR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.71–1.06, p = 0.17; comparing moderate to no pain: AOR: 1.11, 95% CI: 0.95–1.28, p = 0.20; comparing severe pain to no pain: AOR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.84–1.12, p = 0.70. This sample was restricted to individuals who had elevated blood pressure at the index visit and had a subsequent visit within 180 days (n = 9084 people).

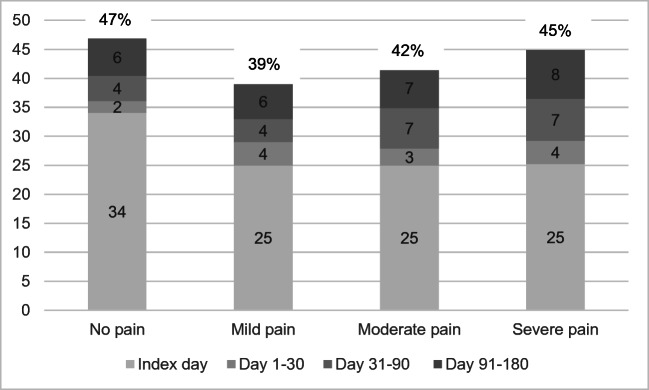

Medication Intensification at the Index Visit

Among patients who had elevated BP at the index visit, patients with pain less often received medication intensification than did patients without pain (25% versus 34%, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Compared to patients without pain, the adjusted odds of receiving an antihypertensive on the index day were 0.65 (95% CI: 0.54–0.80) for mild pain, 0.61 (95% CI: 0.52–0.72) for moderate pain, and 0.55 (95% CI: 0.47–0.64) for severe pain. Within the following 180 days, medication intensification was still more common among patients who reported no pain than among patients reporting mild or moderate pain (47% for no pain versus 45% for severe pain, p < 0.01). After adjustment for confounders, the odds of receiving medication intensification within 180 days remained 22–30% lower for patients who reported pain at the index visit.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients being prescribed an antihypertensive medication between 0 and 180 days after having an elevated systolic blood pressure. Using a Kruskal–Wallis equality-of-populations rank test, there was a significant difference between reported severity of pain and prescription for an antihypertensive medication at the index date (p < 0.01) and between days 31 and 90 (p < 0.03) but not between days 1 and 30 (p = 0.56) or 91 and 180 (p = 0.29). Catagory percentages may differ slightly from the total percentage due to rounding.

Subsequent Visits and Blood Pressure Control Within 180 Days of the Index Visit

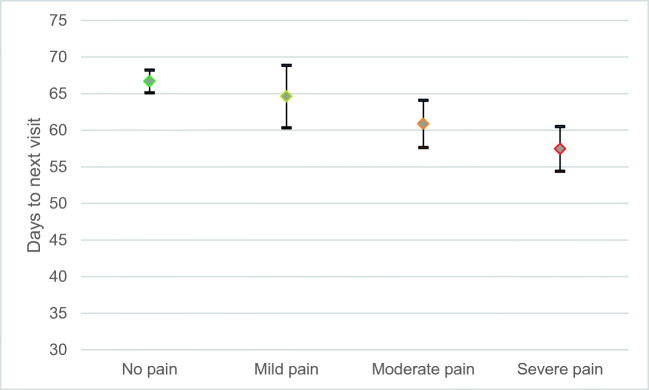

Among patients with an elevated BP at the index visit, patients in moderate pain or severe pain had a subsequent visit significantly earlier than patients reporting no pain (β = 5.8 days for moderate pain; β = 9.2 for severe pain) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted average number of days to the subsequent visit by pain status for patients with elevated blood pressure at the index visit.

We used linear regressions to find the association between report of pain at the index visit and average number of days until the subsequent visit for patients with elevated blood pressure at the index visit. The regression model was adjusted for age, sex, race, marriage, insurance status, number of chronic conditions, and systolic blood pressure at the index visit. Predictive margins are shown. It took 67 (95% CI: 65–68) days for patients in no pain to have their next visit; 64 (95% CI: 60–69) days for patients in mild pain to have their next visit; 61 (95% CI: 58–64) days for patients in moderate pain to have their next visit; and 57 (95% CI: 54–60) days for patients in severe pain. There was no significant difference in time to next visit for patients in mild pain compared with no pain (p = 0.33) but there was a difference comparing moderate pain and severe pain to no pain (p < 0.01). This sample was restricted to individuals who had elevated blood pressure at the index visit and had a subsequent visit within 180 days (n = 9084 people).

Initial pain status was not associated with odds of elevated BP at the subsequent visit (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1). Reporting mild pain was associated with a decrease in average systolic BP at the subsequent visit compared with patients who are in no pain (adjusted β − 1.7 mmHg, 95% CI: − 3.4, − 0.3), even though patients with pain were less likely to receive medication intensification. As seen in Table 2, average adjusted systolic BP at the subsequent visit was in the normal range for patients who reported any category of pain at the index visit.

DISCUSSION

In this large retrospective cohort study, we found that patients who reported severe pain had slightly higher average systolic BP at their index visit compared with patients who reported no pain. In contrast, patients who reported mild or moderate pain had similar BP to patients reporting no pain. Nevertheless, physicians appeared to treat patients in all levels of pain similarly and intensified medications less frequently for all. Despite this disparity, reporting pain at the index visit was not associated with an increased odds of elevated BP at the subsequent visit between 30 and 180 days.

While the relationship between pain and blood pressure is well documented in the experimental setting,5, 8, 9 there is a paucity of research in the clinical setting. Ours appears to be the first large study to address this relationship in primary care. Our findings support the idea that severe pain can elevate BP. We only found one other study, a retrospective review of the quality of hypertension treatment in the emergency department, that simultaneously measured pain and BP.19 Although they found no relationship between severity of pain and initial BP,19 the study was limited to patients with elevated blood pressure and so is not directly comparable.

The complex relationship between pain and elevated BP may create clinical uncertainty for physicians who are considering medication intensification, and uncertainty may induce clinical inertia.20 Others have found that patients who report pain are significantly less likely to receive medication intensification.14, 21 Our study confirms these findings and extends them by examining the longer term impact of medication delays. We found that patients with pain, despite being less likely to have their medication intensified, were just as likely to have their BP controlled at the subsequent visit. These findings suggest that physicians’ delay in treating elevated BP is not associated with harm. This is a counterintuitive finding because we did not find most pain to be associated with elevated BP. Thus, the lack of treatment should have led to persistently elevated BP. One potential explanation is that patients without pain are being over treated. Our dataset does not allow us to test this hypothesis. Future studies should explore which patients with elevated BP need intensification.

Attaining long-term BP control can prevent strokes and cardiovascular diseases which is important for population health, and in 2016, 52% of patients with diagnosed hypertension did not have it adequately controlled.22 Most research has focused on overcoming clinical inertia in order to reach BP control goals.23, 24 Fewer studies have focused on the role of clinical inertia in appropriately delaying intensification,25 but this idea is beginning to gain support. A pair of Italian authors suggested that clinical inertia can serve as a “safeguard for the drug-intensive style of medicine fueled by the current medical literature.”26 More recently, a consensus study of 14 French physicians plus a Delphi panel of 19 international experts identified criteria for appropriate inertia including confirming elevated blood pressure via ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and removing doubt on the reliability of the measurements.25 The United States Preventive Services Task Force found evidence that ambulatory BP monitoring to confirm elevated office BP readings can avoid overtreatment.27 In our study, reporting pain may have added doubt regarding the consistency of the BP measurement with the patient’s true BP, thereby inducing appropriate clinical inertia. In cases of uncertainty, ambulatory BP measurement may be warranted prior to medication intensification.16, 28

This study has several limitations. Patients’ experience of pain was not random and there could be additional unmeasured confounders that affected the relationship between pain, BP, and medication intensification. For example, patients reporting pain may have had more same-day visits with an unfamiliar provider. We did include several important patient demographic and health factors in the regression models and clustered within clinician to account for confounding. Even so, adjustment had little effect on the relationships observed. We could not include medication adherence in our analysis because we do not have pharmacy fill data, but the physicians’ decision-making was reflected by the prescriptions, whether or not they were filled. Nor could we account for the impact of conversations about lifestyle changes that may have occurred during the index visit. Additionally, while pain scores were routinely assessed, documentation of pain scores was not a requirement. Furthermore, our single question about pain would not have identified every patient who has any pain, but it is likely to be sensitive for acute pain and quite specific for any pain. To the extent that we may have incorrectly categorized patients with pain as “no pain,” our results would be biased towards our results the null. Finally, this study was conducted at a single large health system, potentially affecting its external generalizability.

In conclusion, in primary care, the association between pain and increased BP was limited to patients reporting severe pain; despite this, patients reporting any pain were less likely to receive an antihypertensive medication. Even so, pain status did not impact odds of elevated BP at the subsequent visit. In deciding whether to intensify medication, physicians should not consider whether a patient is in pain, unless the pain is severe.

Data Access, Responsibility, and Analysis

Dr. Pfoh had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Chaitoff and Dr. Pfoh are responsible for the data cleaning and analysis.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study was approved by Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Pfoh’s time is supported in part by a National Institute of Health Loan Repayment Grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. All authors report that they have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.The US Burden of Disease Collaborators. Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, et al. The State of US Health, 1990-2016: Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Among US States. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, et al. Potential US Population Impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA High Blood Pressure Guideline. Circulation. 2018;137(2):109–118. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruehl S, Chung OY, Jirjis JN, Biridepalli S. Prevalence of Clinical Hypertension in Patients With Chronic Pain Compared to Nonpain General Medical Patients. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(2):147–153. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton AR, Fazalbhoy A, Macefield VG. Sympathetic Responses to Noxious Stimulation of Muscle and Skin. Front Neurol. 2016;7. doi:10.3389/fneur.2016.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bruehl S, Chung OY. Interactions between the cardiovascular and pain regulatory systems: an updated review of mechanisms and possible alterations in chronic pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28(4):395–414. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al’Absi M, Buchanan T, Lovallo WR. Pain perception and cardiovascular responses in men with positive parental history for hypertension. Psychophysiology. 1996;33(6):655–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1996.tb02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ring C, France CR, Al’Absi M, et al. Effects of Opioid Blockade with Naltrexone and Distraction on Cold and Ischemic Pain in Hypertension. J Behav Med. 2007;30(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruehl S, Carlson CR, McCubbin JA. The relationship between pain sensitivity and blood pressure in normotensives. Pain. 1992;48(3):463–467. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90099-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saccò M, Meschi M, Regolisti G, et al. The Relationship Between Blood Pressure and Pain. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;15(8):600–605. doi: 10.1111/jch.12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazalbhoy A, Birznieks I, Macefield VG. Individual differences in the cardiovascular responses to tonic muscle pain: parallel increases or decreases in muscle sympathetic nerve activity, blood pressure and heart rate: Cardiovascular responses to tonic muscle pain. Experimental Physiology. 2012;97(10):1084–1092. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.066191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz KM, Tanner RM, Falzon L, et al. Visit-to-Visit Variability of Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hypertension. 2014;64(5):965–982. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveria SA, Lapuerta P, McCarthy BD, L’Italien GJ, Berlowitz DR, Asch SM. Physician-Related Barriers to the Effective Management of Uncontrolled Hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):413. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolen SD, Samuels TA, Yeh H-C, et al. Failure to Intensify Antihypertensive Treatment by Primary Care Providers: A Cohort Study in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):543–550. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0507-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krein SL, Hofer TP, Holleman R, Piette JD, Klamerus ML, Kerr EA. More Than a Pain in the Neck: How Discussing Chronic Pain Affects Hypertension Medication Intensification. J GEN INTERN MED. 2009;24(8):911–916. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flint AC, Conell C, Ren X, et al. Effect of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure on Cardiovascular Outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(3):243–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, et al. Benefits and Harms of Intensive Blood Pressure Treatment in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):419. doi: 10.7326/M16-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forchheimer MB, Richards JS, Chiodo AE, Bryce TN, Dyson-Hudson TA. Cut Point Determination in the Measurement of Pain and Its Relationship to Psychosocial and Functional Measures After Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A Retrospective Model Spinal Cord Injury System Analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011;92(3):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Home - Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/home

- 19.Adhikari S, Mathiasen R, Lander L. Elevated blood pressure in the emergency department: lack of adherence to clinical practice guidelines. Blood Pressure Monitoring. 2016;21(1):54–58. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical Inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr EA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Klamerus ML, Subramanian U, Hogan MM, Hofer TP. The Role of Clinical Uncertainty in Treatment Decisions for Diabetic Patients with Uncontrolled Blood Pressure. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(10):717. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, Zhang G, Kruszon-Moran D. Hypertension Prevalence and Control Among Adults: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;289:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mu L, Mukamal KJ. Treatment Intensification for Hypertension in US Ambulatory Medical Care. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(10). doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Milman T, Joundi RA, Alotaibi NM, Saposnik G. Clinical inertia in the pharmacological management of hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(25):e11121. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lebeau J-P, Cadwallader J-S, Aubin-Auger I, et al. The concept and definition of therapeutic inertia in hypertension in primary care: a qualitative systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15(1):130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giugliano D. Clinical Inertia as a Clinical Safeguard. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1591. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, Margolis KL, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP. Diagnostic and Predictive Accuracy of Blood Pressure Screening Methods With Consideration of Rescreening Intervals: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(3):192. doi: 10.7326/M14-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moran AE, Odden MC, Thanataveerat A, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Hypertension Therapy According to 2014 Guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):447–455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]