Abstract

Background

Older adults’ uptake of influenza and pneumococcus vaccines is insufficient worldwide. Although patient experience of primary care is associated with vaccine uptake in children, this relationship remains unclear for older adults.

Objective

This study examined the association between patient experience of primary care and influenza/pneumococcal vaccine uptake in older adults.

Design and Methods

We conducted a multicentered cross-sectional survey involving 25 primary care institutions in urban and rural areas in Japan. Participants were outpatients aged ≥ 65 years who visited one of the participating institutions within the 1-week study period. We assessed patient experience of primary care using the Japanese version of the Primary Care Assessment Tool (JPCAT), which includes six domains: first contact (accessibility), longitudinality (continuity of care), coordination, comprehensiveness (services available), comprehensiveness (services provided), and community orientation. We used a generalized linear mixed-effects model to adjust for clustering within institutions and individual covariates.

Key Results

One thousand participants were included in the analysis. After adjusting for clustering within institutions and other possible confounders, influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake was positively associated with JPCAT total scores (odds ratio per 1 standard deviation increase: 1.19, 95% confidence interval: 1.01–1.40 and odds ratio: 1.26, 95% confidence interval: 1.08–1.46, respectively). Of the JPCAT domains, coordination and community orientation were associated with influenza vaccine uptake and longitudinality, coordination, and comprehensiveness were associated with pneumococcal vaccine uptake.

Conclusions

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake were positively associated with patient experience of primary care in older adults. Consideration of patient experience, particularly longitudinality, coordination, comprehensiveness, and community orientation, could improve vaccine uptake.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-06187-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: older adults, patient experience, vaccination

INTRODUCTION

The provision of preventive medicine is an important role in primary care1 and vaccination is a major part of this role. Therefore, vaccination coverage is an important quality indicator for primary care. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations for older adults have been recommended by the US Preventive Service Task Force and Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)2, 3, because previous studies reported that they reduced disease prevalences.4, 5

However, despite these recommendations, vaccination coverage among older adults for influenza decreased 3.1 percentage points to 70.4% from 2014–2015 to 2015–2016, and over one-third of older adults did not receive pneumococcal vaccination in the USA.6 Moreover, the European Center for Disease and Prevention reported that vaccine coverage targets were not reached in the European Union.7 Therefore, vaccine coverage in older adults is an important issue in many countries. The coverage may be affected by various factors: race, education, income, insurance, a primary care provider, and health status.8

In Japan, influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations have been recommended by the government for people aged ≥ 65 years.9, 10 However, the proportions of people who received influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations in Japan in 2017 were insufficient at 49.0% and 33.0%, respectively.11 Regarding Japanese vaccination policy, local governments offer partial funding for routine influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations for older adults.12 Because vaccinations should be administered only by a physician or a nurse under a direction by a physician13, 14, people visit hospitals or clinics for inoculation.

Patient experience (PX) is quality indicator for patient-centeredness, which is an important measure in healthcare quality.15 PX is defined as the provision of care that is respectful of and responsive to patients’ preferences, needs, and values.15 PX can be used to evaluate attributes of primary care such as access, continuity, coordination, comprehensiveness, and community orientation.16 Moreover, a framework has been developed for quality improvement based on PX in each clinic/hospital.17, 18 As PX is associated with clinical effectiveness, considering PX could be useful in promoting preventive care.19–21 Although PX in primary care is associated with patients’ acceptance of preventive medicine such as cancer screening22, existing interventions to improve vaccination coverage have not taken PX into account.23

Previous research examining PX and vaccine uptake has targeted children and showed a positive relationship between continuity of care and vaccine uptake.24, 25 However, the relationship between PX and vaccine uptake was nonsignificant in older adults.26 Consequently, the relationship between PX and vaccine uptake in older adults remains unclear.

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the association between PX and influenza/pneumococcal vaccine uptake in older adults in primary care. The results of the study could provide a foundation for the development of effective interventions involving PX, to improve vaccination coverage.

METHODS

Design

The study involved a multicentered cross-sectional survey, the Primary Care Organizations Reciprocal Evaluation Survey Study (PROGRESS) 2018. The PROGRESS was conducted by a practice-based research network in Japanese primary care. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kyoto University, Japan (approval number R1342).

Setting

The PROGRESS is a biannual cross-sectional survey to improve quality of care. The survey has collected data regarding PX, health-related quality of life, health conditions, healthcare utilization, clinical process, and sociodemographic characteristics in adult outpatients in Japanese primary care settings since 2015. The 25 participating institutions are distributed throughout both urban and rural areas (Kanto, Tyubu, Hokuriku, Kinki, and Kyusyu; Supplemental Appendix 1). These institutions include 19 clinics and 6 hospitals with fewer than 200 beds. We included the small- and medium-sized hospitals into the study because, in Japan, primary care has been offered not only in a clinic but also in a small hospital.27 A self-completion questionnaire was distributed to all outpatients aged 20 years and older who visited one of the participating institutions within the 1-week survey period between February and March 2018. The surveys were delivered by a receptionist in each participating institution. The participants completed the anonymous survey, put it into envelope, and posted it into the collection box in each institution by themselves. The ethical committee at the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine provided ethical approval for the study (approval number: R1342).

Inclusion Criteria

All patients aged ≥ 65 years who participated in the PROGRESS 2018 were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients without usual source of care and patients who have usual source of care other than the participating institutions were excluded from the study. This was because JPCAT is a questionnaire to assess patient experience of a patient who has usual source of care, and this study aims to investigate the association between patient experience of a patient who has usual source of care and vaccination status. Patients’ usual sources of care were recorded via three questionnaire items, and the algorithms used in the Japanese version of the Primary Care Assessment Tool (JPCAT)28 were identical to those used in the original Primary Care Assessment Tool Adult Expanded Edition, as follows16: (1) Is there a doctor that you usually go if you are sick or need advice about your health?; (2) Is there a doctor that knows you best as a person?; and (3) Is there a doctor that is most responsible for your health care? Patients were considered to have a usual source of care if they answered any of the three questions positively.

Measures

All variables were evaluated using a self- administered questionnaire.

Primary Outcomes: Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccine Uptake

The following two items were used to explore vaccination status: “have you received an influenza vaccination within the past year?” and “have you ever received a pneumococcal vaccination?” The reason for the inclusion of these items was that the CDC recommended annual influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations for older adults.3 We omitted shingles and tetanus vaccination because these vaccinations have not been included into routine vaccination in Japan.29

Explanatory Variable: PX in Primary Care

We used the JPCAT28 to measure PX in primary care. The JPCAT, based on the Primary Care Assessment Tool Adult Expanded Edition,16 was developed using the Delphi method, cognitive testing, and a validation study to establish its applicability to the Japanese healthcare system. The 29-item tool includes six multi-item subscales representing five primary care attributes including first contact, longitudinality, coordination, comprehensiveness, and community orientation.30 We employed total score of the JPCAT as main exposure and score of each domain as secondary exposure. The analysis for the secondary exposure was exploratory analysis. The brief description of each domain is the following:

First contact: The care is first sought from the primary care provider when a new health or medical needs arises. The services must be accessible and used by the population each time a new need or problem arises. The JPCAT mainly assesses PX regarding out-of-hours care in primary care setting.

Longitudinality: This refers to the longitudinal use of a regular source of care over time, regardless of the presence or absence of disease or injury. The JPCAT mainly assesses whether the patient feels that their primary care physician recognizes them as a whole person.

Coordination: The essence of coordination is “the availability of information about prior and existing problems and services, and the recognition of that information as it bears on needs for current care.” The JPCAT mainly assesses PX regarding referral to the specialist in the past.

Comprehensiveness (services available): This refers to the availability of a wide range of services in primary care and their appropriate provision across the entire spectrum of types of needs for all but the most uncommon problems in the population by a primary care provider. In the “services available,” the JPCAT mainly assesses whether the patient feels that the patient can receive care for mental health, dementia, and advanced care planning if necessary.

Comprehensiveness (services provided): In the “service provided,” the JPCAT mainly assesses PX regarding appropriate advice about daily habits in the past.

Community orientation: This refers to care that is delivered in the context of the community. The JPCAT mainly assesses PX regarding home visits and whether the patient feels that their primary care physician is interested in not only individual health problems but also the problems in the community.

Details of the content of the JPCAT are available in Supplemental Appendix 2.

The JPCAT scoring system is structured as follows: responses are provided using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. The mean item scores in each domain are multiplied by 25 to yield domain scores ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better PX. The total score is calculated as the mean score for the six domains and reflects the overall quality of core primary care attributes. The JPCAT has demonstrated good reliability and validity.28 A difference of 3 points or more in the JPCAT is regarded as clinically meaningful in magnitude.31–34

Covariates

We included age, sex, years of education, annual household income, and self-related health as covariates because of their known associations with vaccine uptake and PX. PX is associated with age, sex, socioeconomic status, income, education, and self-rated health.35–38 Vaccine uptake can also be affected by age, socioeconomic status, and self-rated health.8, 39, 40

Statistical Analysis

To determine whether vaccination uptake was associated with JPCAT total scores, we used a generalized linear mixed-effects model (random intercept model) that included random effects for institution and covariates (age, sex, years of education, annual household income, and self-rated health) as fixed effects. The model incorporated the random intercept for institutions, using centering within the cluster. To allow for uncertainty in the missing values for independent and dependent variables, we used multiple imputations by fully conditional specification, which included JPCAT scores, age, sex, years of education, annual household income, self-rated health, and vaccination status. We calculated 95% confidence intervals using robust standard errors. The statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

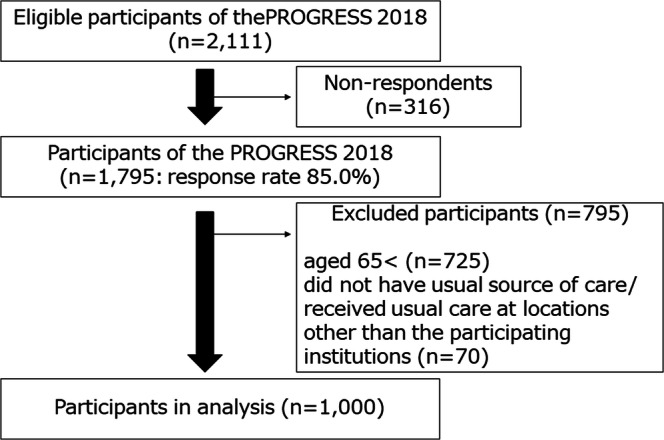

Of the 2111 eligible participants, 1795 (85.0%) provided survey responses. Of these, 795 were excluded, because 725 were aged < 65 years and 70 did not have usual source of care or received usual care at locations other than the participating institutions. Therefore, we ultimately analyzed data for 1000 respondents (444 men, 525 women, and 31 individuals with missing data). Figure 1 shows the patient flowchart for the study. Table 1 summarizes respondents’ characteristics: 23.6% were aged ≥ 80 years, 70.9% had not attended college, and 53.9% reported an annual household income below 3 million JPY (27,000 USD).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart.

Table 1.

Patients’ Characteristics (N = 1000)

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 444 (44.4) |

| Female | 525 (52.5) |

| No response | 31 (3.1) |

| Age (year) | |

| 65–69 | 254 (25.4) |

| 70–79 | 510 (51.0) |

| 80 or more | 236 (23.6) |

| No response | 0 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 285 (28.5) |

| High school | 424 (42.4) |

| Junior college | 97 (9.7) |

| More than or equal to college | 157 (15.7) |

| No response | 37 (3.7) |

| Annual household income (million JPY) | |

| < 3.00 (≒ 27,000 US dollar) | 539 (53.9) |

| 3.00–4.99 | 247 (24.7) |

| 5.00–6.99 | 71 (7.1) |

| 7.00–9.99 | 17 (1.7) |

| ≧ 10.00 | 12 (1.2) |

| No response | 114 (11.4) |

| Self-rated health status | |

| Excellent | 18 (1.8) |

| Very good | 155 (15.5) |

| Good | 563 (56.3) |

| Poor | 222 (22.2) |

| Very poor | 26 (2.6) |

| No response | 16 (1.6) |

| Number of other sources of care | |

| 0 | 414 (41.4) |

| 1 | 367 (36.7) |

| 2 | 147 (14.7) |

| ≥ 3 | 42 (4.2) |

| No response | 30 (3.0) |

| Influenza vaccination | |

| Vaccinated | 680 (68.0) |

| Unvaccinated | 288 (28.8) |

| No response | 32 (3.2) |

| Pneumococcal vaccination | |

| Vaccinated | 538 (53.8) |

| Unvaccinated | 420 (42.0) |

| No response | 42 (4.2) |

Table 2 lists the means and standard deviations for the JPCAT scores. Of a possible score of 100, the average JPCAT score was 66.7. The highest scoring domain was longitudinality (80.8), while the lowest scoring domain was comprehensiveness of services provided (42.3). Table 3 demonstrates JPCAT scores and vaccine uptake and presents the results of the generalized mixed-effect model analysis of the association between PX with vaccine uptake. After adjusting for possible confounders and clustering within institutions, higher total JPCAT scores were significantly associated with influenza vaccine uptake (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] per 1 SD increase: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.01–1.40) and pneumococcal vaccine uptake (aOR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.08–1.46). Regarding individual PX domains, coordination (aOR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.05–1.48) and community orientation (aOR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.01–1.39) were associated with influenza vaccine uptake. In addition, longitudinality (aOR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.04–1.38), coordination (aOR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.14–1.54), and comprehensiveness (service provided; aOR: 1.16, 95% CI: 1.00–1.35) were associated with pneumococcal vaccine uptake.

Table 2.

Distribution of JPCAT, and Unadjusted Associations with Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccination

| Total (N = 1000) | Influenza vaccination (N = 968) | Pneumococcal vaccination (N = 958) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated (N = 680) | Unvaccinated (N = 288) | Vaccinated (N = 538) | Unvaccinated (N = 420) | ||||

| p value* | p value* | ||||||

| JPCAT | |||||||

| Total score | 66.7 (14.3) | 67.8 (14.3) | 64.5 (14.0) | 0.002 | 68.2 (14.0) | 65.0 (14.3) | < 0.001 |

| First contact | 62.0 (23.6) | 61.9 (24.0) | 61.7 (22.8) | 0.898 | 61.6 (25.3) | 62.1 (21.4) | 0.784 |

| Longitudinality | 80.8 (15.3) | 81.7 (15.1) | 78.7 (15.0) | 0.005 | 81.9 (14.7) | 79.4 (15.6) | 0.012 |

| Coordination | 69.7 (24.5) | 71.9 (23.9) | 65.1 (24.9) | < 0.001 | 73.2 (23.5) | 65.7 (24.7) | < 0.001 |

| Comprehensiveness (services available) | 69.0 (23.3) | 70.4 (23.2) | 66.2 (23.2) | 0.030 | 69.7 (22.5) | 68.3 (24.2) | 0.428 |

| Comprehensiveness (services provided) | 42.3 (28.6) | 43.5 (29.2) | 39.6 (27.1) | 0.099 | 44.6 (29.0) | 39.3 (27.6) | 0.013 |

| Community orientation | 72.3 (18.7) | 73.7 (18.3) | 69.1 (19.2) | < 0.001 | 74.2 (17.4) | 70.1 (20.1) | < 0.001 |

JPCAT Japanese version of Primary Care Assessment Tool

Distribution: Mean (SD)

*p value by Student’s t test

Table 3.

Associations of JPCAT Scores with Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccinations (N = 1000)

| Influenza vaccination | Pneumococcal vaccination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI)† | p value | aOR (95% CI)† | p value | |

| JPCAT* | ||||

| Total score | 1.19 (1.01–1.40) | 0.040 | 1.26 (1.08–1.46) | 0.003 |

| First contact | 0.96 (0.80–1.15) | 0.638 | 1.09 (0.92–1.28) | 0.317 |

| Longitudinality | 1.13 (0.97–1.32) | 0.119 | 1.19 (1.04–1.38) | 0.014 |

| Coordination | 1.25 (1.05–1.48) | 0.010 | 1.32 (1.14–1.54) | < 0.001 |

| Comprehensiveness (services available) | 1.05 (0.89–1.24) | 0.545 | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) | 0.888 |

| Comprehensiveness (services provided) | 1.09 (0.92–1.29) | 0.314 | 1.16 (1.00–1.35) | 0.047 |

| Community orientation | 1.18 (1.01–1.39) | 0.043 | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) | 0.067 |

JPCAT Japanese version of Primary Care Assessment Tool, aOR adjusted odds ratio

Random intercept model, adjusted for age, sex, education, household income, and self-rated health status. Each score was included individually in the model

*Ranging from 0 to 100 points; centering within cluster

†Per 1SD increase

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that PX of primary care attributes was positively correlated with vaccine uptake. In particular, longitudinality, coordination, comprehensiveness (service provided), and community orientation were associated with vaccine uptake in older Japanese adults.

Better PX can promote preventive care such as immunization as well as screening services in diabetes, dyslipidemia, and cancer screening.41–45 The possible mechanism is that better PX enhances adherence to preventive activities.20 Also, improved PX may be related to the acceptance of providers’ recommendations regarding vaccination. The reason is that a previous study conducted in Japan demonstrated that the most trusted source of information for patients regarding vaccine uptake was healthcare workers.46 However, whether improving PX can cause better use of preventative care still remains unclear. Our future research will aim to investigate causality between improving PX and use of preventative service.

As we mentioned in the “INTRODUCTION,” the previous study conducted in the UK did not demonstrate significant correlations between PX and vaccine uptake among older adults.26 The inconsistency in the results between the previous UK study and the current study could be explained by a difference in confounding factors.26 While the previous UK study adjusted only for age, sex, and economic status,26 the current study included educational status and self-rated health, which are believed to be associated with both PX and vaccine uptake.39, 40 Moreover, the difference of the measure could affect the results. The previous UK study used the General Practice Assessment Survey (GPAS) as the index of PX.26 The GPAS has included evaluation for receptionists and nurses.26, 47 On the other hand, the JPCAT focused on evaluation for physicians.28 However, the current results provide information related to the potential mechanism underlying patients’ choice regarding vaccine uptake. Moreover, the findings suggest that considering PX when developing interventions17 may be associated with improving vaccination coverage in primary care settings. Interventions considering PX could be meaningful by combining with other interventions which have demonstrated the effectiveness in the previous systematic review such as client reminders/recalls, reminders to physician, and enhancement of vaccination access.23 Although the findings demonstrated the positive effect of PX on vaccine uptake, the decision-making process involving patients and doctors remains unclear. In future, observation of communication regarding vaccine uptake in clinical practice could enhance understanding of the decision-making process.17 Moreover, the inclusion of both staff and patients in discussion regarding vaccine uptake might be important for quality improvement.17

Among the JPCAT domains, the coordination exerted a positive effect on both influenza and pneumococcal vaccination uptake. In a previous study that included patients of all ages, coordination was positively correlated with the provision of preventive care.24 The reason for this finding could be that coordination is essential when providing preventive care to patients who are visiting multiple providers.24 In the current study, because more than half of the participants had two or more regular providers, coordination between multiple providers could be associated with better vaccine uptake. In addition, longitudinality, comprehensiveness (services provided), and community orientation had tendency to be positively correlated with vaccine uptake. This finding could have occurred because longitudinality means continuous use of a regular source of care over time,16 comprehensiveness implies that primary care facilities offer diverse care,16 and community orientation refers to involvement in health care for the community.16 For instance, longitudinality may be related to a recommendation from medical staff and knowledge about vaccine uptake.48–50 Also, community orientation can promote patient outreach such as invitations for vaccine uptake by retired teachers.51

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to demonstrate a positive correlation between PX and vaccine uptake in older adults. The findings were based on data from a nationwide multicenter, practice-based study examining primary care, which was conducted by a research network and included both urban and rural areas. As PX and vaccination status vary between institutions, we adjusted for clustering within institutions using a generalized linear mixed-effects model and allowed appropriate patient-level analysis.

The study was subject to several potential limitations. First, we evaluated vaccine uptake based on patients’ survey responses. Therefore, if patients with lower PX had forgotten their vaccination status, the analysis could have overestimated the relationship between PX and vaccine uptake. However, self-reported influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake is highly sensitive in older adults.52 Consequently, this limitation might not have affected the results. Second, information bias potentially can affect the results. However, we employed the methods to minimize the bias such as the anonymous survey and collection. Third, the study was a 1-year study. Therefore, there might be temporal trends in use of vaccinations that were not accounted for. Fourth, although we determined covariates based on the previous literature, unknown confounding factors can influence the results. Fifth, we tested multiple hypotheses. However, we only carried out the tests which were planned in the protocol. Therefore, correction for multiple comparisons may be unnecessary.53 Because each domain is the secondary exposure, we need to pay attention to interpret the results. Finally, the participating institutions were interested in the quality of care. The tendency can affect the better vaccine uptake in the participating institutions compared with the national data.11 Therefore, the results should be generalized to other institutions with caution.

In conclusion, better PX was associated with better vaccine uptake in older adults. To achieve better vaccination coverage, consideration of PX, particularly longitudinality, coordination, comprehensiveness, and community orientation, could be helpful.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 38 kb).

(DOCX 23 kb).

Acknowledgments

We thank the primary care facilities that participated in the PROGRESS 2018 for their contribution.

Funding

This work was supported by Institute for Health Economics and Policy, Japan.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because we did not receive informed consent concerning data sharing from the participants.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kyoto University, Japan (approval number R1342).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

We presented about part of this study at the annual conference of the Japanese Primary Care Association in May 2019.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Makoto Kaneko and Takuya Aoki are equal contribution.

References

- 1.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maciosek MV, LaFrance AB, Dehmer SP, et al. Updated priorities among effective clinical preventive services. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(1):14–22. doi: 10.1370/afm.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Vaccines are Recommended for You. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/index.html. Accessed Aug 5, 2019.

- 4.Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Al-Ansary LA, Ferroni A, Rivetti A, Pietrantonj CD. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(2):CD001269. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki M, Dhoubhadel BG, Ishifuji T, et al. Serotype-specific effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults aged 65 years or older: a multicentre, prospective, test- negative design study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(3):313–321. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30049-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination coverage among adults in the United States, National Health Interview Survey, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/pubs-resources/NHIS-2016.html. Accessed Aug 5, 2019.

- 7.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in Europe, Overview of Vaccination Recommendations and Coverage Rates in the EU Member States for the 2012–13 Influenza Season. Available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Seasonal-influenza-vaccination-Europe-2012-13.pdf. Accessed Aug 5, 2019.

- 8.Kamal KM, Madhavan SS, Amonkar MM. Determinants of adult influenza and pneumonia immunization rates. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(3):403–411. doi: 10.1331/154434503321831120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. About system for vaccination. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r98520000033079-att/2r985200000330hr_1.pdf. Accessed Aug 5, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 10.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. About pneumococcal vaccination for older adults. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou/haienkyukin/index_1.html. Accessed Aug 5, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 11.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Number of people who received routine immunization. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/bcg/other/5.html. Accessed Aug 5, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 12.Shimazawa R, Ikeda M. The vaccine gap between Japan and the UK. Health Policy. 2012;107(2-3):312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Outlines to provide vaccination. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/bcg/tuuchi/2.html. Accessed May 5, 2020. (in Japanese)

- 14.Act on Public Health Nurses, Midwives, and Nurses. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/web/t_doc?dataId=80078000&dataType=0&pageNo=1. Accessed May 5, 2020. (in Japanese)

- 15.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: The National Academic Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the adult primary care assessment tool. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):161–175. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The King’s Fund. The Patient-Centred Care Project: Evaluation report. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Patient-centred-care-project.pdf. Accessed Aug 5, 2019.

- 18.Dorset County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. National Cancer Patient Experience Programme

- 19.National Survey. Available at: https://www.quality-health.co.uk/resources/surveys/national-cancer-experience-survey/2010-national-cancer-patient-experience-survey/2010-south-west-strategic-health-authority/230-dorset-county-hospital-nhs-foundation-trust-1/file. Accessed Aug 5, 2019.

- 20.Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):522–554. doi: 10.1177/1077558714541480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Aoki T, Inoue M. Primary care patient experience and cancer screening uptake among women: an exploratory cross-sectional study in a Japanese population. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2017;16(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12930-017-0033-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas RE, Russell M, Lorenzetti D. Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD005188. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005188.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flocke SA, Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ. The association of attributes of primary care with the delivery of clinical preventive services. Med Care. 1998;36(8 suppl):AS21–30. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):159–166. doi: 10.1370/afm.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao M, Clarke A, Sanderson C, Hammersley R. Patients’ own assessments of quality of primary care compared with objective records based measures of technical quality of care: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2006;333(7557):19–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38874.499167.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato D, Ryu H, Matsumoto T, et al. Building primary care in Japan: Literature review. J Gen Fam Med. 2019;20(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Aoki T, Inoue M, Nakayama T. Development and validation of the Japanese version of Primary Care Assessment Tool. Fam Pract. 2016;33(1):112–117. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. About vaccine preventable disease. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou/yobou-sesshu/index.html. Accessed Aug Jan, 2020. (in Japanese)

- 31.Starfield B. Primary Care Balancing Health Care Needs, Services and Technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lied TR, Sheingold SH, Landon BE, Shaul JA, Cleary PD. Beneficiary reported experience and voluntary disenrollment in Medicare managed care. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;25(1):55–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paddison CA, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, et al. Experiences of care among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD: Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey results. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(3):440–449. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren FC, Abel G, Lyratzopoulos G, et al. Characteristics of service users and provider organisations associated with experience of out of hours general practitioner care in England: population based cross sectional postal questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2015;350:h2040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aoki T, Miyashita J, Yamamoto Y, et al. Patient experience of primary care and advance care planning: a multicentre cross-sectional study in Japan. Fam Pract. 2017;34(2):206–212. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JL, Ramsay J, Green J. Age, gender, socioeconomic, and ethnic differences in patients’ assessments of primary health care. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(2):90–95. doi: 10.1136/qhc.10.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao H, Barber JP. The effect of perceived health status on patient satisfaction. Value Health. 2008;11(4):719–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyratzopoulos G, Elliott M, Barbiere JM, et al. Understanding ethnic and other socio-demographic differences in patient experience of primary care: evidence from the English General Practice Patient Survey. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):21–29. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sizmur S, Graham C, Walsh J. Influence of patients’ age and sex and the mode of administration on results from the NHS Friends and Family Test of patient experience. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20(1):5–10. doi: 10.1177/1355819614536887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrew MK, McNeil S, Merry H, Rockwood K. Rates of influenza vaccination in older adults and factors associated with vaccine use: a secondary analysis of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takayama M, Wetmore CM, Mokdad AH. Characteristics associated with the uptake of influenza vaccination among adults in the United States. Prev Med. 2012;54(5):358–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabana MD, Jee SH. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J Fam Pract. 2004;53(12):974–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drotar D. Physician behavior in the care of pediatric chronic illness: association with health outcomes and treatment adherence. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(3):246–254. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ed42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sans-Corrales M, Pujol-Ribera E, Gené-Badia J, Pasarín-Rua MI, Iglesias-Pérez B, Casajuana-Brunet J. Family medicine attributes related to satisfaction, health and costs. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):308–316. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsiao CJ, Boult C. Effects of quality on outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23(4):302–310. doi: 10.1177/1062860608315643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wada K, Smith DR. Mistrust surrounding vaccination recommendations by the Japanese government: results from a national survey of working-age individuals health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramsay J. The General Practice Assessment Survey (GPAS): tests of data quality and measurement properties. Fam Pract. 2000;17(5):372–379. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.5.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakamoto A, Chanyasanha C, Sujirarat D, Matsumoto N, Nakazato M. Factors associated with pneumococcal vaccination in elderly people: a cross-sectional study among elderly club members in Miyakonojo City, Japan. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1172. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nowalk MP, Zimmerman RK, Shen S, Jewell IK, Raymund M. Barriers to pneumococcal and influenza vaccination in older community-dwelling adults (2000-2001) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klett-Tammen CJ, Krause G, Seefeld L, Ott JJ. Determinants of tetanus, pneumococcal and influenza vaccination in the elderly: a representative cross-sectional study on knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) BMC Public Health. 2016;16:121. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2784-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krieger JW, Castorina JS, Walls ML, Weaver MR, Ciske S. Increasing influenza and pneumococcal immunization rates: a randomized controlled study of a senior center-based intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(2):123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mac Donald R, Baken L, Nelson A, Nichol KL. Validation of self-report of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status in elderly outpatients. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(3):173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34(5):502–508. doi: 10.1111/opo.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 38 kb).

(DOCX 23 kb).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because we did not receive informed consent concerning data sharing from the participants.