INTRODUCTION

Care models that integrate behavioral health services into primary care, such as the collaborative care model, have not been broadly adopted despite their demonstrated effectiveness.1 One prominent explanation for this limited adoption is that important components of integrated behavioral health care, such as care management and collaboration between primary care clinicians and behavioral health specialists, were not typically reimbursed by insurers.2 To accelerate the adoption of behavioral health integration (BHI) for primary care practices, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced new fee-for-service Medicare payment codes for BHI services on January 1, 2017. We examined the use of these new codes in their first two years of existence, 2017 and 2018.

METHODS

CMS introduced four new BHI payment codes to support enhanced care teams. These codes cover patient assessment, management, and treatment directed by the treating clinician, in consult with a psychiatric consultant, and delivered by a behavioral health care manager (BHM) as a supplement to usual care. The treating clinician bills G0502 and G0503 codes (changed to CPT 99492-99493 in 2018) for 60–70 BHM service minutes spent in a month. G0504 (CPT 99494) is a monthly add-on code for 30 additional service minutes. G0507 (CPT 99484) indicates 20 minutes of monthly services and coordination for more general behavioral health case management with a designated care team member (not necessarily a BHM, and not requiring psychiatric consult).

We used a 5% sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiary claims from 2017 and 2018 to identify all visits with a BHI code, capturing the specialty of the billing provider and primary diagnosis associated with BHI services. We calculated the total number of billed BHI visit-months, the number of unique beneficiaries receiving BHI services, unique providers billing for BHI, and BHI visit-months billed per beneficiary. Finally, we estimated the number of beneficiaries potentially eligible for BHI services as the number of beneficiaries with any behavioral health (i.e., F00-F99) ICD-10 diagnoses. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt human subjects research.

RESULTS

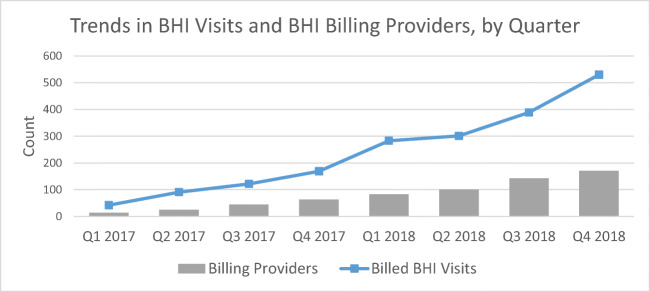

In our sample, 711 unique beneficiaries received 1927 visits with BHI services (Table 1), representing 0.1% of beneficiaries with a behavioral health diagnosis (N = 815,110). Among BHI recipients, 51.2% received at least two months of services (average of 2.7 visit-months billed per beneficiary). The most common primary diagnoses for BHI visits were mood disorders (39%). The majority of billed BHI codes (75%) were for general case management services (G0507/CPT 99484). Providers billing for these services were primarily primary care physicians (51.7%) or advanced care practitioners (26.4%). The total number of BHI visits and billing providers, though very small, grew steadily during the two years (Fig. 1).]-->

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries Receiving BHI Services

| Total unique beneficiaries receiving BHI (2017 and 2018) | 711 |

| Beneficiaries with behavioral health diagnosis in 2017 or 2018 | 815,110 |

| By beneficiary: | |

| Average number of BHI visit-months per beneficiary | 2.7 (SD 2.8) |

| Number of BHI visit-months per beneficiary | |

| 1 | 347 (48.8%) |

| 2 | 127 (17.9%) |

| 3 | 72 (10.1%) |

| 4 | 54 (7.6%) |

| 5+ | 111 (15.6%) |

| By BHI visit: | |

| Total number of BHI visit-months, by code type | 1927 |

| G0502/CPT 99492 | 222 (11.5%) |

| G0503/CPT 99493 | 263 (13.6%) |

| G0507/CPT 99484 | 1442 (74.8%) |

| Primary Dx associated with use of BHI service code | |

| Mood disorders | 750 (38.9%) |

| Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders | 344 (17.9%) |

| Mental disorders, unspecified | 221 (11.5%) |

| Dementia, delirium, or other mental disorders due to known physiological condition | 127 (6.6%) |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders | 94 (4.9%) |

| Other behavioral health diagnosis | 80 (4.2%) |

| Other diagnosis, non-behavioral health | 310 (16.1%) |

| By Provider: | |

| Number of unique providers billing for BHI services | 344 |

| Internal medicine | 95 (27.6%) |

| Family practice | 83 (24.1%) |

| Nurse practitioner | 72 (20.9%) |

| Physician’s assistant | 19 (5.5%) |

| Psychiatrist | 24 (7.0%) |

| Social worker | 14 (4.1%) |

| Other | 37 (10.8%) |

Data are from the 2017 5% Medicare Fee-for-Service annual sample, and Quarters 1–4 of the 2018 5% Medicare Fee-for-Service quarterly samples. Approximately 13% of beneficiary-months had multiple BHI codes billed. Per CMS billing guidelines, we retained only one reimbursed BHI service code per beneficiary per month in final sample (i.e., duplicates removed; when multiple different codes present, we retained the highest-intensity billing code that was accepted for reimbursement)

Figure 1.

Trends in BHI visits and BHI billing providers, by quarter. Data are from the 2017 5% Medicare Fee-for-Service annual sample, and Quarters 1–4 of the 2018 5% Medicare Fee-for-Service quarterly samples.

DISCUSSION

CMS created new fee-for-service Medicare payment codes to increase the delivery of integrated behavioral health care, but these codes were used minimally in their first two years. Providers most often billed for general case management that does not require BHM or psychiatrist consultation, suggesting insufficient infrastructure and processes to support more robust BHI services. Indeed, early adopters of BHI codes have struggled to implement feasible and sustainable staffing, care delivery, and billing practices.3 Other codes for similar enhanced coordination services (e.g., Chronic Care Management) also experienced low initial take-up, though not to the same extent.4 This suggests that the structural investments required for BHI services may be particularly challenging.

Current reimbursements may be insufficient to catalyze BHI service adoption.5 For the more resource-intensive BHI service codes (i.e., those requiring psychiatrist consultation and 60–70 minutes of care delivery by a BHM), other mechanisms might be required to support upfront structural investments, such as a per-member per-month payments based on number of patients potentially eligible for BHI services (i.e., based on diagnosis). Organizationally, practices with low or uncertain BHI service volumes could explore sharing personnel and contract structures with other local practices, and consider how to utilize staff that can deliver and bill for both behavioral health and other types of care management.3

Use of BHI codes in the first two years was low, but grew steadily. Identifying the characteristics of participating provider organizations, and the clinical utilization patterns of BHI service users, will help inform payment policy and organizational implementation strategies that can support BHI as part of more comprehensive care management infrastructure.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: Evidence update 2010–2015. Milbank Memorial Fund: New York, NY; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Press MJ, Howe R, Schoenbaum M, et al. Medicare Payment for Behavioral Health Integration. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):405–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1614134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlo AD, Baden AC, McCarty RL, Ratzliff AD. Early Health System Experiences with Collaborative Care (CoCM) Billing Codes: a Qualitative Study of Leadership and Support Staff. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Agarwal SD, Barnett ML, Souza J, Landon BE. Adoption of Medicare’s Transitional Care Management and Chronic Care Management Codes in Primary Care. JAMA. 2018;320(24):2596–2597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwenk TL. Integrated behavioral and primary care: what is the real cost? JAMA. 2016;316(8):822–823. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]