Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this article is to explore concerns regarding sections of the federal workers’ compensation law that apply to the treatment and management of work-related injuries of federal employees by chiropractors, and to offer a call to action for change.

Discussion

A 1974 amendment to the Federal Employees’ Compensation Act (FECA) stipulates that chiropractic services rendered to injured federal workers are reimbursable. However, the only reimbursable chiropractic treatment is “manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist.” This means the chiropractor must take radiographs in order to be reimbursed. As with other health care professions, chiropractors are expected to practice according to best practices guided by studies in the scientific literature. Yet in the federal workers’ compensation arena, this law requires chiropractors to practice in a manner that is fiscally wasteful, contradicts current radiology standards, and may expose patients to unnecessary X-ray radiation. Presently, there is discord between what the law mandates, chiropractic training and scope, and what professional guidelines recommend. In this article we discuss how FECA creates problems in the following 7 categories: direct harm, indirect harm, contradiction of best practices, ethical dilemma, barriers to conservative treatment, fiscal waste, and discrimination.

Conclusion

The 1974 FECA provision requiring chiropractors to take radiographs regardless of presenting medical necessity should be updated to reflect current chiropractic education, training, and best practice. To resolve this discrepancy, we suggest that the radiographic requirement and the limitations placed on chiropractic physicians should be removed.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, Radiology, Medicare, Workers’ Compensation

Introduction

Presently, chiropractors are reimbursed for treating injured federal workers under the Federal Employees’ Compensation Act (FECA). Chiropractic treatment and services are limited to “manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by x-ray to exist.”1 This is counter to current best practices. The Division of Federal Employees’ Compensation (DFEC) Procedure Manual states:

The term “physician” is defined at 5 U.S.C. 8101 to include licensed medical doctors, surgeons, podiatrists, dentists, clinical psychologists, optometrists, chiropractors, and osteopathic practitioners within the scope of their practice as defined by state law.

…

“Medical, Surgical, and Hospital Services and Supplies” includes services and supplies provided or prescribed by physicians and medical facilities defined above within the scope of their practice as defined by state law, except that a chiropractor is considered to be a “physician” only when a subluxation of the spine has been diagnosed by X-ray, and treatment is limited to manual manipulation of the spine. However, if chiropractic treatment is prescribed by a qualified physician, treatment other than manipulation of the spine may be authorized.1

It is important to understand how this situation came about. As is often the case, the political history of the legislation affecting the chiropractic profession is complex and convoluted. After explaining the history and evolution of our current legal dilemma, we will explain the problems this creates and the need for updated and modernized legislation.

In the early 1970s, the chiropractic profession realized 2 landmark legislative accomplishments. One was coverage of chiropractic treatment in Medicare and Medicaid. The other was the inclusion of chiropractic in the care of federal employees in federal workers’ compensation programs. These legislative achievements occurred during a period of vigorous opposition to chiropractic by the American Medical Association, which had fought an intensive, decade-long effort to contain and eliminate chiropractic as a profession and limit the inclusion of chiropractic services in mainstream health care.2,3

Coverage of chiropractic care was not unfettered, however. Each legislative amendment restricted coverage to a particular federal definition of chiropractic, limiting care to specific treatment parameters. As important as these legislative achievements were at the time, the limitations affected later federal legislation that also had an adverse impact on chiropractic patients.

Medicare

In 1972, the Social Security Amendments (SSA), Public Law 92-603, added chiropractors to the definition of “physicians” for Medicare and Medicaid, effective July 1, 1973, but with the following service stipulation:

A chiropractor who is licensed as such by the State (or in a State which does not license chiropractors as such, is legally authorized to perform the services of a chiropractor in the jurisdiction in which he performs such services), and who meets uniform minimum standards promulgated by the Secretary, but only for the purpose of sections 1861(s)(1) and 1861(s)(2)(A) and only with respect to treatment by means of manual manipulation of the spine (to correct a subluxation demonstrated by X-ray to exist) which he is legally authorized to perform by the State or jurisdiction in which such treatment is provided.4 (emphasis added)

Section 275 of the SSA added chiropractic services to the joint federal and state Medicaid program as well, so long as the state covered the services of a chiropractor, but only for manual manipulation of the spine.4 No mention was made of the necessity to demonstrate a chiropractic vertebral subluxation by radiograph under the Medicaid-providers portion of the SSA.4

Since the 1972 SSA, chiropractors have been defined as “physicians” for the purposes of Medicare but “only with respect to treatment by means of manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation demonstrated by X-ray to exist.” Paradoxically, although the law required a radiograph for the manual treatment to be reimbursable, the radiograph itself was not reimbursable. By the 1990s, however, it was increasingly recognized that the indiscriminate use of X-rays, which are a form of ionizing radiation, posed serious health risks to both patients and providers. Furthermore, advances in research have shown that the biomechanical lesions of the spine that chiropractors treat may be more accurately and efficiently identified by less invasive tests and measures.

The American Chiropractic Association (ACA) prevailed upon Congress to eliminate the mandate that chiropractors take radiographs of patients to demonstrate the existence of a chiropractic vertebral subluxation for Medicare and Medicaid patients when President Clinton signed into law the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Public Law 105-33, effective as of 2000.5 Section 4513 of this law repealed the requirement for the taking of a radiograph to demonstrate the existence of a subluxation to obtain reimbursement for chiropractic services. and directed the secretary of health and human services to “develop and implement utilization guidelines relating to the coverage of chiropractic services under part B of title XVIII of the Social Security Act in cases in which a subluxation has not been demonstrated by X-ray to exist”6 (emphasis added).

Federal Employees’ Compensation Act

According to the Library of Congress's Congressional Research Service, FECA

has its origins in a law from the late 1800s that covered only the employees of a federal agency that has long since ceased to exist on its own. The modern FECA system has its roots in legislation enacted in 1916. Many of the basic provisions of this original law, such as the basic rate of compensation, are still in effect today. Congress passed major amendments to the 1916 legislation in 1949, 1960, 1966, and most recently in 1974. Although these amendments made significant changes to the FECA program, the basic framework of the program endures as does the overall intent of Congress through the years to maintain a workers’ compensation system for federal employees that is in line with the basic principles that have governed workers’ compensation in this country for a century.7

One of the purposes of FECA was to bring the federal government's adoption of workers’ compensation principles in line with similar statutes enacted by the individual states.

Like the Medicare amendment to the Social Security Act 2 years earlier, FECA, as amended in 1974, included chiropractors in the definition of a “physician” in the federal workers’ compensation program. Like Medicare, FECA amended section 8101(2) of the federal workers’ compensation law with the stipulation that

the term “physician” includes chiropractors only to the extent that their reimbursable services are limited to treatment consisting of manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist, and subject to regulation by the Secretary.4, 8(emphasis added)

Similarly, the 1974 statute amended section 8101(3) of the act, indicating that “reimbursable chiropractic services are limited to treatment consisting of manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist, and subject to regulation by the Secretary”9 (emphasis added).

Although the 1974 legislative amendments to FECA added chiropractors to the list of physicians covered by the act, this action was similar to the 1972 SSA adding chiropractors to the list of physicians covered by Medicare, with nearly identical limitations. There were also important statutory and regulatory differences.

For example, the 1972 Medicare amendment comes within the regulatory oversight and enforcement of the US Department of Health and Human Services (formerly the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare), through the operation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration). In contrast, the 1974 legislation modifying FECA comes solely within the regulatory jurisdiction of the US Department of Labor.

So although the ACA managed to get an amendment passed in 1997 altering the Medicare statute to strike the mandate requiring a chiropractor to demonstrate the existence of a subluxation by X-ray, no similar legislative effort or amendment was made, then or since, to update FECA. Consequently, in order to obtain reimbursement for chiropractic care and treatment of injured federal workers under FECA, doctors of chiropractic are still required to demonstrate the existence of a chiropractic vertebral subluxation by obtaining a radiograph. Thus, in order to be reimbursed for care and treatment of those patients who do not need radiographs, chiropractors are required to expose them to unnecessary X-ray radiation under FECA.

The scope of practice for doctors of chiropractic in most areas of the United States includes evaluation and management services, the authority to order and interpret diagnostic and laboratory studies, and the use of many other forms of treatment. However, this obsolete statute limits chiropractors to reimbursement only for manual manipulation of the spine to correct a chiropractic vertebral subluxation shown by radiographs to exist, and disregards the other services associated with chiropractic care.

Family and Medical Leave Act

Almost twenty years after the 1974 amendments to FECA were enacted, Congress passed the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) in 1993.10 Like FECA, the FMLA comes within the regulatory oversight and enforcement of the US Department of Labor (DOL). Initially, the FMLA did not include chiropractic or chiropractors, or many other categories of care providers, within the statutory definition of a “health care provider.” However, the law stipulated that other classes of providers could be included within the definition of a “health care provider” at the discretion of the secretary of labor. The act defined a “health care provider” as

(A) a doctor of medicine or osteopathy who is authorized to practice medicine or surgery (as appropriate) by the State in which the doctor practices; or (B) any other person determined by the Secretary to be capable of providing health care services.11 (emphases added)

Chiropractors and other classes of health care provider were not specifically included or excluded in the FMLA per se but could be included at the discretion of the secretary of labor pursuant to the act. The FMLA charged the secretary of labor with crafting the necessary regulations to carry out the intent of the act.12

In drafting suitable rules to manage, regulate, and enforce the FMLA, the secretary of labor used the FECA definition of “physician” for determining what services and benefits would be included and covered under the FMLA regulations. For example, in the June 4, 1993, issue of the Federal Register outlining the “Interim Final Rule” the DOL proposed to administer the FMLA, the draft regulations asked, “What Is a ‘Health Care Provider’?” In response, the DOL noted:

FMLA defines a “health care provider” as a doctor of medicine or osteopathy who is authorized to practice medicine or surgery (as appropriate) by the State in which the doctor practices; orany other person determined by the Secretary to be capable of providing health care services. Many employer commenters asked that the definition be limited to doctors of medicine or osteopathy; others wanted providers of a broad range of medical services to be included. Because health care providers will need to indicate their diagnosis in health care certificates, such a broad definition was considered inappropriate.

After review of definitions under various programs, including OPM rules and Medicare, the definition of “physician” under the Federal Employees’ Compensation Act, 5 U.S.C. 8101.2, was used in these regulations as a starting point, which also includes podiatrists, dentists, clinical psychologists, optometrists, and chiropractors (limited to treatment consisting of manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist) authorized to practice in the State and performing within the scope of their practice as defined under State law. In addition, nurse practitioners and nurse-midwives who provide diagnosis and treatment of certain conditions, especially at health maintenance organizations and in rural areas where other health care providers may not be available, are included in the definition, provided they are performing within the scope of their practice as allowed by State law.13 (emphases added)

On January 6, 1995, the department of labor adopted the FMLA final rule effective February 5, 1995, preserving within the regulation the determination of exactly which health care providers covered under this act would fall under the rule. Chiropractors were included under section 825.118 of the Final Rule:

§ 825.118 What is a “health care provider”?

(a) The Act defines “health care provider” as:

(1) A doctor of medicine or osteopathy who is authorized to practice medicine or surgery (as appropriate) by the State in which the doctor practices; or

(2) Any other person determined by the Secretary to be capable of providing health care services.

(b) Others “capable of providing health care services” include only:(1) Podiatrists, dentists, clinical psychologists, optometrists, and chiropractors (limited to treatment consisting of manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist) authorized to practice in the State and performing within the scope of their practice as defined under State law.14 (emphases added)

In the same manner, chiropractors were also included under the label “health care providers” defined in subpart H of the Final Rule at 29 CFR 825.800.15

The ACA objected to the limitation the DOL imposed on chiropractic with the promulgation of the FMLA regulation.16 However, it appears that DOL regulators did not address the ACA's objection, likely because the limitations that applied to chiropractic were also found in the 1972 Medicare statute—Social Security Act 1861(r)(5), 42 USC 1395x(r)(5), which was still active in 1995 (the Medicare statute did not eliminate the X-ray requirement until 1997, effective 2000)—and because the same limitation imposed by FECA was (and is still) valid law as well.17

In the years that have intervened since the SSA the 1974 FECA amendments, the shortcomings in the 1972 amendments to Medicare have been partially remedied. The stipulation under Medicare that chiropractors demonstrate the existence of a chiropractic vertebral subluxation on radiographs was eliminated by Congress as a health and safety measure in 1997, effective in 2000. The ACA had prevailed upon Congress to eliminate the mandatory X-ray requirement to demonstrate the existence of a subluxation when President Clinton signed the Balance Budget Act of 1997 into law.6 Unfortunately, to our knowledge, no similar effort to eliminate the identical requirement in FECA has taken place, and the limitations imposed on chiropractic care and treatment in FECA remain. As we noted earlier, the language of FECA has had an adverse effect on the development of federal rules underpinning the regulation and enforcement of the FMLA as well.

For these reasons, it is our contention that the statutory requirement limiting reimbursable chiropractic services to treatment “consisting of manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist” should be removed from the FECA statute. Since both the 1974 FECA statute and the 1995 FMLA regulations are administered by the US Department of Labor, it is our understanding that once FECA is amended legislatively to eliminate the requirement, this will allow the profession to confront the FMLA rule, which is based in part on the X-ray requirement found in FECA law.

Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs

Although FECA does not force a chiropractor to obtain radiographs of a patient, that is the only way to be reimbursed for any services. This mandate is found within the FECA, both in the FECA “Procedure Manual, Part 5 0200,4.a.1” and in “FECA Section 8101.Definitions.” The FECA is within the Division of Federal Employees' Compensation which is under the Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP) which is under the US Department of Labor.18 FECA states that “reimbursable” services require demonstration by X-ray. That word “reimbursable” is pivotal to the business of health care, and leverages the provider into either compliance or nonparticipation. If a chiropractor does not obtain imaging, it is immaterial whether the procedure is medically unnecessary for the patient or not—the OWCP will not reimburse for any of the treatment for that patient. This potentially creates an environment of unnecessary X-ray exposure for patients.

Stipulations are repeated in other areas of federal rules and regulations relating to FECA, replicating the troubling situation. For example, the DFEC Procedure Manual, part 5-0200.4, reiterates these stipulations verbatim. Consequently, claims managers at DFEC are required by federal laws and regulations to enforce FECA according to its terms. However, at least 1 OWCP office has indicated that although the statute specifically requires that doctors of chiropractic radiograph injured federal workers, the OWCP will accept other imaging methods (eg, a computerized tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) in place of radiographs (personal communication).

Discussion

A radiograph is a diagnostic image produced by exposing a person to X-rays, which are a type of ionizing radiation. The lay public uses the term “X-ray” when referring to a radiograph. Radiographs are typically ordered to identify suspected lesions or rule out conditions that may influence clinical decision making and treatment. They are a useful clinical tool, and when applied properly they may assist in diagnosing various musculoskeletal conditions. However, the chiropractic profession recognizes that radiographs should not be performed without good reason, because of radiation exposure. Chiropractors have developed diagnostic imaging practice guidelines, which are based on current evidence and are in concordance with other radiological guidelines.22, 19, 20, 21

Mandatory exposure of patients to X-rays is neither an inconvenient technicality nor a profit center for a chiropractic provider. We argue that this mandate creates issues of patient safety, poorer outcomes, ethical dilemmas, and fiscal burdens.

To clarify, we are not discussing whether radiographs should or should not be used in any particular case; that would be a topic for a different discussion. Chiropractors should be allowed to take radiographs when indicated. Here, we discuss the indiscriminate use of X-ray radiation imposed upon every chiropractic patient as dictated by law, instead of the appropriate use of radiography based on clinical decision making for each individual chiropractic patient.

Best practices and practice guidelines are developed and updated to help practitioners achieve the best possible outcomes with the lowest possible risk of harm and in the most cost-effective way.22, 19, 20, 21 The science that directs patient care has changed enormously since the enactment of the 1972 SSA and the 1974 FECA amendments. The decision to obtain imaging for a patient should be made by the health care professional and the patient in that specific situation after weighing the benefits and risks of diagnostic options in light of the best current scientific evidence. No procedure, especially one that exposes a patient to radiation, should be forced upon an entire population of patients in a preordained and indiscriminate manner by a congressional mandate created nearly 50 years ago based on half-century-old concepts. Unfortunately, this is what FECA does.

We suggest that FECA creates problems that fall into 7 categories:

-

•

Direct harm

-

•

Indirect harm

-

•

Contradiction of best practices

-

•

Ethical dilemma

-

•

Barriers to conservative treatment

-

•

Fiscal waste

-

•

Discrimination

Direct Harm

There is well-recognized harm from exposure to ionizing radiation, and accumulation can lead to an increased risk of cancer.23,24 Although there is no established strict scale to measure specific damage from specific doses, many experts agree that no amount of radiation is “safe.” Decisions to expose a patient to a procedure with risk must include clinical consideration of the offsetting weight of the benefit. No other health care service is required to expose patients to X-rays as part of normal care. We propose that the mandated requirement for radiographs for reimbursed chiropractic care is a health risk for federal employees because of unnecessary exposure to X-rays.

Indirect Harm

Indiscriminate use of imaging may produce indirect harms that are not balanced by potential benefits.25,26 There is a risk of having a negative impact on patient outcomes and recovery when a patient sees incidental imaging findings. This effect can be enhanced by a patient's possible misunderstanding of the medical terminology used by radiologists and clinicians in describing normal findings or relatively unimportant variants.27 These exposures may cause unwarranted concern, lead the patient to “catastrophizing” their condition, and cause “labeling.”25,28,29 Imaging may also result in the “medicalization” of low back pain owing to its “visually exquisite depiction of pathoanatomy and a misguided belief that these findings are a cause of their pain.”26 The patient may seek unneeded follow-up tests for incidental findings, such as unnecessary surgery, which may lead to additional unnecessary costs.30 Patients may believe that their pain will not improve until the imaging findings have resolved, which may increase the risk of developing chronic pain.31 Iatrogenic effects of early MRI include worse disability, increased medical costs, and increased rates of surgery, all unrelated to the severity of the injury.30 We propose that the mandated requirement for radiographs for reimbursed chiropractic care increases the potential for indirect harm to federal employees.

Contradiction of Best Practices

The premise of FECA's requirement for radiographs—that they are a necessary or reasonable method of identifying or monitoring functional lesions—is not supported by the current scientific literature. At present, there is no scientific evidence for the association of static radiographs with the success of chiropractic manipulation. There are more valid, efficient, and reliable methods for identifying chiropractic vertebral subluxations or mechanical lesions that do not expose patients to unnecessary radiation. Currently, there is no evidence that mechanical spine pain is associated with abnormal radiographic findings. There is evidence that radiographs are useful in clinical practice to rule out fractures or other pathologies, but these findings are uncommon in asymptomatic people.32 When spine pain is relieved and function restored, some abnormalities found on radiographs may still be present on subsequent images. There are currently no data available to support a relationship between changes in alignment or other structural characteristics and patient improvement.33 Because imaging findings cannot measure the extent of pain or limitations, once any potential pathologies are ruled out the treatment approach should be determined by the clinical presentation, and the focus should be on maximizing function.26,34

Current best practices and guidelines suggest that imaging is not advised for all patients presenting for treatment of conditions amenable to chiropractic care.37, 34, 35, 36 These best practices inform practitioners that the use of imaging studies might be indicated by the presence of certain established “red flags” that might appear within the history gathering and physical examination. These red flags could indicate the reasonable possibility of the presence of some condition that would make manipulation inappropriate in terms of either safety or efficacy, or inform the provider to consider a possible need for referral. These red flags might include, for example, trauma significant enough to create reasonable suspicion of a fracture, based on the patient's age, condition, and any serious underlying medical conditions such as cancer or osteoporosis. Imaging might also be indicated when a reasonable trial of care has failed to produce results. In the absence of red flags, however, imaging likely offers no benefit and may have a negative impact on outcomes that would amount to substandard care.25,26,30,31,40, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39

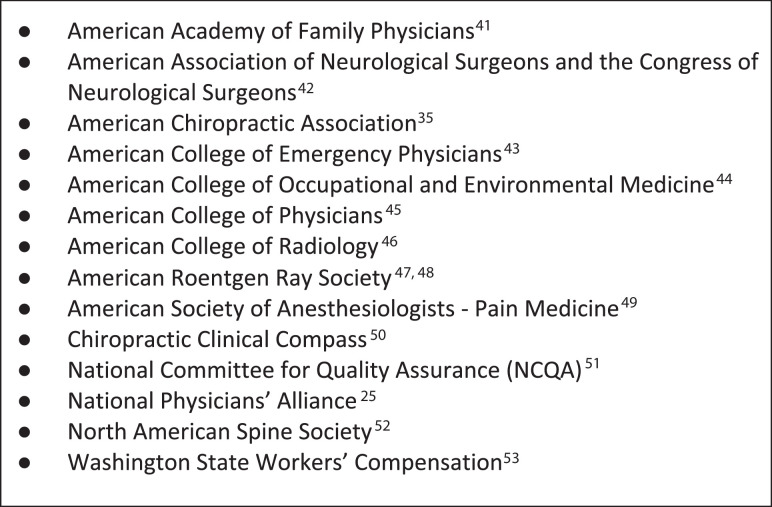

For patients presenting with nonspecific low back pain and no red flags, early imaging does not improve outcomes compared with proceeding with conservative treatment without imaging, and not imaging patients with acute low back pain will thus reduce harms and costs without affecting clinical outcomes.25,40 Avoiding routine early imaging in the absence of specific red flags is embraced across the health care spectrum and by virtually all neuromusculoskeletal health care fields and their representative organizations (Fig 1).53, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 Compliance with best practice imaging guidelines is 1 of the performance measures established by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services under the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, further demonstrating that it is a widely accepted standard.54

Fig 1.

Other societies that have advised against early imaging for nonspecific low back pain in the absence of red flags.25, 35,53, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52

For these reasons, we propose that the FECA X-ray mandate undermines the delivery of quality care to federal employees.

FECA undermines the assertion of the necessity of radiographs. The premise of the requirement is that a static radiograph is necessary for a chiropractor to see if a joint in the spine requires manipulation, and that a spinal dysfunction (ie, chiropractic vertebral subluxation) cannot be identified by any other examination procedures. The other concern is that the statute requires the use of X-ray for the first treatment but not for any follow-up treatments. The statute implies that the radiographic finding (eg, manipulable lesion or chiropractic vertebral subluxation) will be there forever and will not resolve with treatment, and thus a follow-up radiograph would not be necessary. Because the characteristics of the spine on imaging that serve to meet the statute's definition of chiropractic vertebral subluxation are not going to change with treatment,33 strict adherence to imaging findings would theoretically lead to permanently ongoing care, which does not make any sense. We propose that the mandated requirement for radiographs for reimbursed chiropractic care is contrary to best practices.

Ethical Dilemma

The FECA requirement in law and regulations presents chiropractors with a moral and ethical dilemma. The chiropractic physician wants to do what is best for the work-injured federal employee. However, to qualify for reimbursement after treating patients with no red flags or clinical indicators that require radiographs, the chiropractor is required to expose the patient to unnecessary ionizing radiation. This scenario compromises the best possible outcomes and offers no benefit in return. Reimbursement for the imaging is an added source of income, but it is an unnecessary expense to the payer. In this situation, the chiropractor must choose from 3 options when faced with a patient who could benefit from chiropractic care but who does not have clinical indications for radiographs:

-

1.

Refuse to expose the federal employee to unnecessary ionizing radiation, thus turning away a patient who is likely to benefit from chiropractic care.

-

2.

Refuse to expose the federal employee to unnecessary ionizing radiation and treat the patient pro bono, knowing there will be no reimbursement.

-

3.

Expose the federal employee to unnecessary ionizing radiation. In doing so, the chiropractor is forced to compromise his or her professional integrity and rationalize the need to irradiate injured federal workers indiscriminately where no evident need exists, in order to provide treatment to those in need of chiropractic care and still comply with the FECA statute and regulations.

These scenarios demonstrate how the statute creates an untenable paradox for conscientious providers. Any law that would bind a caregiver to potentially cause harm and compromise their ethics needs to be realigned with current knowledge and best practices.

Another ethical contradiction complicates this further. The FECA guidelines state that providers “may be excluded from participation in the Federal Employees’ Compensation Program through an administrative process” if they “provide excessive or substandard treatment.”55 The unnecessary imaging studies that FECA requires would be “excessive” and “substandard” in terms of contemporary care protocols. We propose that the mandated requirement for radiographs for reimbursed chiropractic care creates an untenable ethical dilemma.

Barriers to Conservative Treatment

FECA limits the options available for chiropractors to provide care for work-injured federal employees. The DFEC Procedure Manual states that chiropractors are considered physicians “within the scope of their practice as defined by state law.”1 But this statement is countered 2 paragraphs later with a limiting exception that says “treatment is limited to manual manipulation of the spine”1 (emphasis added), which is a very small component of the full scope of chiropractic practice.56

Chiropractors can provide a variety of treatment and case management options in addition to spinal manipulation. These include other manual therapy techniques, patient education, home exercise plans, rehabilitation, biomechanical training, ergonomic improvements, and healthy lifestyle coaching, in addition to a multitude of modalities.61, 57, 58, 59, 60 Chiropractic education and scope of practice covers the entire musculoskeletal system and is not limited to the spine. Chiropractic physicians are the only providers limited to less than their full scope of practice by FECA. This creates a barrier by limiting conservative treatment options that could be offered to injured federal employees, thereby reducing their access to care and their chances for success.

Currently, our nation is in crisis, facing increasing opioid addictions and deaths and trying to prevent further addictions by prioritizing the treatment of painful injuries with conservative interventions. Conservative treatments for musculoskeletal pain, such as those offered by chiropractors, should be considered an additional part of the solution. For example, a recent study evaluated the association between utilization of chiropractic services for treatment of low back pain and use of prescription opioids. Although no direct causal relationship was established, it discovered a “significantly lower” likelihood of an adverse drug event in recipients of chiropractic services than in nonrecipients.62 In the Joint Commission's revised pain management standards and strategies, hospitals are instructed to provide nonpharmacologic treatment modality options within their facilities and/or by referral outside their facility, including chiropractic therapy.63 The Joint Commission lists spinal manipulation, such as that offered by chiropractors, as one of the evidence-based, non-opioid options medical doctors should consider referring to when treating pain.64 We propose that by limiting what care chiropractors can offer to federal employees, FECA creates a barrier to additional conservative care services.

Fiscal Waste

The direct and indirect costs of diagnostic imaging must be considered. Depending on the number of spinal regions imaged and the type of imaging used, the direct cost could range from $175 to $699 for radiographs, and if the provider chooses MRI, the cost could be more than $7436 in a given region of the country.65 Of course, these costs are justified if the studies are medically necessary. However, in the absence of red flags, routine imaging in the first few weeks of care for acute low back pain has shown to produce no outcome benefit, and national best practice guidelines echo similar cautions regarding neck injuries.57 As a consequence, the monies expended on imaging performed to document a subluxation of the spine must be considered dollars wasted. There are additional indirect costs to consider, such as the effect on the mental health of the patient. Iatrogenic effects of early MRI suggest worse disability and increased rates of surgery, all unrelated to the severity of the injury and all unnecessarily increasing medical costs.30 A fiscal burden that does not result in a benefit can be categorized as waste. We argue that this is fiscally irresponsible, especially when waste is created through a mandate.

Discrimination

The statute discriminates against a regulated a licensed health care profession in the United States. No other category of physician defined under either the SSA or FECA has been subjected to such limitations. In addition, Congress left it up to secretary of labor to decide the types of providers eligible to certify leave from employment under the FMLA. The secretary of labor used FECA as the regulatory touchstone in deciding what professions and professionals could certify a patient for leave under the FMLA. Consequently, under the FMLA chiropractors may only certify leave and treat federal workers under FMLA (“limited to treatment consisting of manual manipulation of the spine to correct a subluxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist”). In the meantime, the Social Security Act was amended to remove a similar stipulation placed upon the chiropractic profession by Medicare.

FECA also exhibits a fundamental misunderstanding of the conditions that chiropractors treat and the chiropractic scope of practice. For example, rehabilitative exercises, stretching, and posture exercises are within the scope of chiropractic practice. However, FECA does not allow these to be performed by a chiropractor in the workers’ compensation arena unless the patient has been referred for those services by a medical doctor or osteopath. We propose that this discriminates against a licensed health care profession and severely limits the quality of care that chiropractors can offer federal employees.

Call to Action

The conditions that existed in 1974 and stimulated Congress to impose limitations upon chiropractic treatment no longer exist. The clinical knowledge that directs patient care has advanced greatly. The portion of FECA that forces chiropractic physicians to take radiographs and indiscriminately expose every patient to ionizing radiation is out of step with current health care best practices and is no longer scientifically defensible, ethically tenable, or fiscally responsible.

The current law disregards the nuanced clinical thought processes necessary in deciding whether imaging will be beneficial for a patient and what type of imaging should be obtained for the specific presentation. Clinical decisions should be made as a team by the doctor and patient, guided by the standards of best available science, clinical expertise, and patient preferences. FECA does not support evidence-based, outcome-focused, efficacy-prioritized health care for injured federal employees. We argue that because the detrimental effects of FECA occur on an ongoing basis, the need for change qualifies as being urgent.

The only course for bringing these changes to fruition is through Congress. We encourage the leaders of our state and national organizations to reach out to Congress to encourage them to amend FECA to be more closely in sync with current knowledge and standards. We encourage providers and patients to support their national and state organizations in this regard and to contact their legislators to make them aware of the need for modernization.

Under the current DFEC policies, an injured federal employee cannot receive optimal chiropractic treatment that follows established best practices and assures the best chances for a favorable outcome. Lower quality of care is certainly not the intent of FECA. It is also not the statute's intent to force a patient away from his or her first choice of provider, as evidenced in its expressed intent to allow the patient to have that choice.66

It is incumbent on Congress to enact necessary changes to existing laws when they are outdated, run counter to their original intent, and no longer comport with contemporary knowledge and best practices. The need for change becomes even more urgent when an existing law poses a considerable risk to the health and safety of patients, namely federal workers in this case. Therefore, we call upon federal regulators and legislators to take a fresh look at FECA. Evidence supports our assertion that chiropractic treatment should be included in evidence-based nonpharmacologic treatment for safe and effective care of injured federal employees.

Limitations

The arguments provided here are the opinions and thoughts of the authors based on the presentation of the available data. We did not perform a systematic analysis; therefore, our conclusions are limited to those used in this article.

Conclusion

The FECA statute requiring chiropractors to take radiographs regardless of presenting medical necessity should be updated to reflect current chiropractic education, training, and best practice standards. To resolve this discrepancy, we suggest that the X-ray requirement and the limitations placed upon chiropractic physicians should be removed.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): J.J.A., K.C.K., W.M.W.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): J.J.A., K.C.K., W.M.W.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): J.J.A., K.C.K., W.M.W.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): J.J.A., K.C.K., W.M.W.

Literature search (performed the literature search): J.J.A., K.C.K., W.M.W.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): J.J.A., K.C.K., W.M.W.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): J.J.A., K.C.K., W.M.W.

Practical Applications.

-

•

The Federal Employees’ Compensation Act creates problems that fall into 7 categories.

-

•

The 7 categories are: direct harm, indirect harm, contradiction of best practices, ethical dilemma, barriers to conservative treatment, fiscal waste, and discrimination.

-

•

We offer a call to action for the X-ray requirement and the limitations placed on chiropractic physicians to be removed.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

References

- 1.Division of Federal Employees’ Compensation Procedure Manual. FECA Part 5-0200,4.a. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/owcp/dfec/regs/compliance/DFECfolio/FECA-PT5/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 2.Wilk v AMA, 895 F2d 352 (7th Cir 1990); cert. denied, 496 US 927, 110 SCt. 2621 (1990), and 498 US 982, 111 SCt 513 (1990)

- 3.Agocs S. Chiropractic's fight for survival. AMA J Ethics. 2011;13(6):384–388. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2011.13.6.mhst1-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Social Security Amendments Act of 1972, Publ. L 92-603, 42 USC 1395x. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg1329.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2020

- 5.Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Publ L 105-33, 111 Stat. 251; Aug 5, 1997. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-105publ33/pdf/PLAW-105publ33.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2020.

- 6.Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Public Law 105-33

- 7.Szymendera SD. Congressional Research Service; Washington, DC: 2020. The Federal Employees’ Compensation Act (FECA): Workers’ Compensation for Federal Employees. Report No. R42107, version 24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Code (USC), Title 5–Government Organization and Employees, Part III–Employees, Subpart G–Insurance and Annuities, Chapter 81–Compensation for Work Injuries, Subchapter I–Generally, § 810 –Definitions as amended by HR 13871, Publ. L. 93-416, 88 Stat. 1143, September 7, 1974. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-88/pdf/STATUTE-88-Pg1143.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2019.

- 9.An Act to Amend Chapter 81 of Subpart G of Title 5, United States Code, Relating to Compensation for Work Injuries, and for Other Purposes, 88 Stat 1143.

- 10.Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, Publ L 103-3, 107 Stat 6; Feb 5, 1993. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg6.pdf#page=1. Accessed November 9, 2020.

- 11.Family and Medical Leave Act, 107 Stat 6.

- 12.Family and Medical Leave Act, 107 Stat 6, §404.

- 13.Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division 29 CFR 825. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993. Federal Register 1993 Jun 4; 58(106): 31794-31874. Available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/archives.federalregister.gov/issue_slice/1993/6/4/31790-31874.pdf#page=5. Accessed November 9, 2020. [PubMed]

- 14.Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division 29 CFR 825. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993: Final Rule Federal Register 1995 Jan 6; 60(4): 2180-2279. § 825.118 What is a “health care provider”? (p. 2245) Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1995-01-06/pdf/94-32342.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2020. See also: Title 29 - Labor Part 825 - THE FAMILY AND MEDICAL LEAVE ACT OF 1993 Subpart A - What is the Family and Medical Leave Act, and to Whom Does It Apply? Section 825.118 - What is a “health care provider”? Subtitle B - Regulations Relating to Labor (Continued) Chapter V - WAGE AND HOURDIVISION,DEPARTMENT OF LABOR Subchapter C - OTHER LAWS July 1, 2002 Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2002-title29-vol3/pdf/CFR-2002-title29-vol3-sec825-118.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2020.

- 15.The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 Final Rule. Fed Regist. 1995;60(4):2266. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 Final Rule. Fed Regist. 1995;60(4):2198. [Google Scholar]

- 17.5 U.S.C. United States Code, 2011 Edition Title 5--GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION AND EMPLOYEES PART III--EMPLOYEES. Subpart G--nsurance and Annuities CHAPTER 81--COMPENSATION FOR WORK INJURIES SUBCHAPTER I--GENERALLY. Sec. 8101--Definitions Section 8101(2)--Physician. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title5/html/USCODE-2011-title5-partIII-subpartG-chap81-subchapI-sec8101.htm. Accessed November 9, 2020.

- 18.Federal Employees’ Compensation Act, 5 USC 8101(2).

- 19.Bussières AE, Peterson C, Taylor JA. Diagnostic imaging practice guidelines for musculoskeletal complaints in adults—an evidence-based approach: introduction. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(9):617–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bussières AE, Taylor JA, Peterson C. Diagnostic imaging practice guidelines for musculoskeletal complaints in adults—an evidence-based approach: part 1: lower extremity disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(9):684–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bussières AE, Peterson C, Taylor JA. Diagnostic imaging guideline for musculoskeletal complaints in adults—an evidence-based approach—part 2: upper extremity disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(1):2–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bussières AE, Taylor JA, Peterson C. Diagnostic imaging practice guidelines for musculoskeletal complaints in adults—an evidence-based approach—part 3: spinal disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(1):33–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong J-Y, Han K, Jung J-H, Kim JS. Association of exposure to diagnostic low-dose ionizing radiation with risk of cancer among youths in South Korea. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harvard Women's Health Watch. Radiation risk from medical imaging. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/cancer/radiation-risk-from-medical-imaging. Accessed July 14, 2020. [PubMed]

- 25.Srinivas SV, Deyo RA, Berger ZD. Application of “less is more” to low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(13):1016–1020. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flynn TW, Smith B, Chou R. Appropriate use of diagnostic imaging in low back pain: a reminder that unnecessary imaging may do as much harm as good. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(11):838–846. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roland M, van Tulder M. Should radiologists change the way they report plain radiography of the spine? Lancet. 1998;352(9123):229–230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslau J, Seidenwurm D. Socioeconomic aspects of spinal imaging: impact of radiological diagnosis on lumbar spine-related disability. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11(4):218–223. doi: 10.1097/00002142-200008000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher ES, Welch HG. Avoiding the unintended consequences of growth in medical care: how might more be worse? JAMA. 1999;281(5):446–453. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webster BS, Cifuentes M. Relationship of early magnetic resonance imaging for work-related acute low back pain with disability and medical utilization outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(9):900–907. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181ef7e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chou R, Deyo RA, Jarvik JG. Appropriate use of lumbar imaging for evaluation of low back pain. Radiol Clin. 2012;50(4):569–585. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 994;331(2):69-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Choosing Wisely. Do not perform repeat imaging to monitor patients’ progress. Available at:http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/aca-repeat-imaging-to-monitor-progress/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 34.Jenkins HJ, Downie AS, Moore CS, French SD. Current evidence for spinal X-ray use in the chiropractic profession: a narrative review. Chiropr Man Ther. 2018;26(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12998-018-0217-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choosing Wisely. Avoid routine spinal imaging in the absence of clear clinical indicators for patients with acute low back pain of less than six (6) weeks duration. Available at:http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/aca-spinal-imaging-for-acute-low-back-pain/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 36.Clinical Compass. Diagnostic imaging. Available at: http://clinicalcompass.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Diagnostic-Imaging_2017.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 37.Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C. Clinical practice guideline: chiropractic care for low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chou R. Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(3):181–189. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allan GM, Spooner GR, Ivers N. X-ray scans for nonspecific low back pain: a nonspecific pain? Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(3):275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Modic MT, Obuchowski NA, Ross JS. Acute low back pain and radiculopathy: MR imaging findings and their prognostic role and effect on outcome. Radiology. 2005;237(2):597–604. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Academy of Family Physicians. Imaging for low back pain. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/cw-back-pain.html. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 42.Choosing Wisely. Don't obtain imaging (plain radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography [CT], or other advanced imaging) of the spine in patients with non-specific acute low back pain and without red flags. Available at:https://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-association-neurological-surgeons-imaging-for-nonspecific-acute-low-back-pain/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 43.Choosing Wisely. Avoid lumbar spine imaging in the emergency department for adults with non-traumatic back pain unless the patient has severe or progressive neurologic deficits or is suspected of having a serious underlying condition (such as vertebral infection, cauda equina syndrome, or cancer with bony metastasis). Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/acep-lumbar-spine-imaging-in-the-ed/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 44.Choosing Wisely. Don't initially obtain x-rays for injured workers with acute non-specific low back pain. Available at:http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-college-occupational-environmental-medicine-x-rays-for-acute-non-specific-low-back-pain/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 45.Chou R. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choosing Wisely. Don't do imaging for uncomplicated headache. Available at: https://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-college-radiology-imaging-for-uncomplicated-headache/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 47.Gehweiler J, Daffner R. Low back pain: the controversy of radiologic evaluation. Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140(1):109–112. doi: 10.2214/ajr.140.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roudsari B, Jarvik JG. Lumbar spine MRI for low back pain: indications and yield. Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(3):550–559. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choosing Wisely. Avoid imaging studies (MRI, CT or X-rays) for acute low back pain without specific indications. Available at: https://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-society-anesthesiologists-imaging-studies-for-acute-low-back-pain/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 50.Greenstein JS. Re: Choosing wisely public health campaign. Available at:http://www.acatoday.org/Portals/60/Choosing%20Wisely/ChoosingWiselyEndorsementCCGPP_Letter.pdf?ver=2017-09-26-134157-933. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 51.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Use of imaging studies for low back pain (LBP). Available at:https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/use-of-imaging-studies-for-low-back-pain/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 52.Choosing Wisely. Don't recommend imaging of the spine within the first 6 weeks of an acute episode of low back pain in the absence of red flags. Available at:https://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/north-american-spine-society-advanced-imaging-of-spine-within-first-six-weeks-of-non-specific-acute-low-back-pain/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 53.Graves JM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Jarvik JG, Franklin GM. Early imaging for acute low back pain: one-year health and disability outcomes among Washington State workers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37(18):1617–1627. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318251887b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Electronic Clinical Quality Improvement Resource Center. Use of imaging studies for low back pain. Available at: https://ecqi.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/ecqm/measures/CMS166v7.html. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 55.Division of Federal Employees’ Compensation Procedure Manual. FECA Part 5-0200.4.b. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/owcp/dfec/regs/compliance/dfecfolio/feca-pt5/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 56.Chang M. The chiropractic scope of practice in the United States: a cross-sectional survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(6):363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C. Best-practice recommendations for chiropractic management of patients with neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42(9):635–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F. The treatment of neck pain–associated disorders and whiplash-associated disorders: a clinical practice guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(8):523–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bussières AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F. Spinal manipulative therapy and other conservative treatments for low back pain: a guideline from the Canadian chiropractic guideline initiative. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(4):265–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bryans R, Decina P, Descarreaux M. Evidence-based guidelines for the chiropractic treatment of adults with neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(1):42–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bryans R, Descarreaux M, Duranleau M. Evidence-based guidelines for the chiropractic treatment of adults with headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34(5):274–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Goehl JM, Kazal LA. Association between utilization of chiropractic services for treatment of low-back pain and use of prescription opioids. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(6):552–556. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pain assessment and management standards for hospitals. R3 Rep Requirement Rationale References. 2017;11:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Non-pharmacologic and non-opioid solutions for pain management. Quick Safety. 2018;44:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanford Bismarck Medical Center price list. Available at:https://search.hospitalpriceindex.com/hospital/Sanford-Bismarck-Medical-Center-Price-List/5586. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 66.US Department of Labor, Office of Worker's Compensation Programs, Division of Federal Employees’ Compensation. CA-11 when injured at work information guide for federal employees. Available at:https://www.dol.gov/owcp/dfec/regs/compliance/ca-11.htm. Accessed November 6, 2020.