Summary

Background:

Child emotional overeating is a risk factor for obesity that is learned in the home environment. Parents’ use of food to soothe child distress may contribute to the development of children’s emotional overeating.

Objectives:

To examine the effect of a responsive parenting (RP) intervention on mother-reported child emotional overeating, and explore whether effects are mediated by mother-reported use of food to soothe child distress.

Methods:

The sample included primiparous mother-infant dyads randomized to a RP intervention (n = 105) or home safety control group (n = 102). Nurses delivered RP guidance in four behavioral domains: sleeping, fussy, alert/calm, and drowsy. Mothers reported their use of food to soothe at age 18 months and child emotional overeating at age 30 months. Mediation was analyzed using the SAS PROCESS macro.

Results:

RP intervention mothers reported less frequent use of food to soothe and perceived their child’s emotional overeating as lower compared to the control group. Food to soothe mediated the RP intervention effect on child emotional overeating (mediation model: R2 = 0.13, P < .0001).

Conclusions:

Children’s emotional overeating may be modified through an early life RP intervention. Teaching parents alternative techniques to soothe child distress rather than feeding may curb emotional overeating development to reduce future obesity risk.

Keywords: child, emotional overeating, food to soothe, obesity prevention, parent feeding practices, responsive parenting

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Eating in response to negative emotions—“emotional overeating”1—develops early in life2 and is linked to poor diets3 and higher weight status.4 Emotional overeating may reflect deficits in emotion regulation5 and disrupted appetite self-regulation.6 Heritability analyses show that children learn to emotionally overeat in the family home environment,7,8 but evidence related to its aetiology is limited. Parents’ use of non-responsive feeding practices may teach young children that the pleasurable properties of eating can attenuate negative emotions which reinforces emotional overeating.9 The current analysis tests this theory empirically within the context of an early obesity prevention trial designed to promote responsive parenting (RP). RP broadly describes parents’ prompt and developmentally appropriate responses to their child’s cues, including hunger and satiety cues.10

Parents’ use of food to soothe their child’s distress (or “emotional feeding”) may result in overfeeding and limit opportunities for the child to build self-soothing skills.11 Use of food to soothe is associated with increased weight gain in infancy12 and childhood,13 and emotional overeating may play a role in this association.14 Infants who exhibit greater temperamental negativity may elicit parents’ use of food to soothe, and negative affect, which is broadly characterized by a child’s tendency to express fear, sadness, anger, and discomfort,15 may exacerbate the bidirectional, longitudinal association between parent use of food to soothe and child emotional overeating.16 Parental feeding practices are known modifiable intervention targets,17 therefore, teaching parents to use alternative soothing strategies may prevent emotional overeating.

The Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) randomized clinical trial (RCT)18 showed that providing RP guidance to first-time mothers prevented rapid infant weight gain19 and obesity at 3 years20 compared to a home safety control group. INSIGHT’s central hypothesis is that RP anticipatory guidance promotes child self-regulation and shared parent-child responsibility for feeding to reduce children’s risk for overeating and overweight.18 One component of the RP curriculum focused on providing mothers with alternative soothing strategies to feeding.18 Mothers who received the RP intervention reported using food to soothe less frequently than the control group17; however, intervention effects on parental use of food to soothe have not been examined beyond infancy.

This analysis aims to examine the effects of the INSIGHT RP intervention on mother-reported child emotional overeating and determine if effects are mediated by mother-reported use of food to soothe child distress. We hypothesize that mothers receiving the RP intervention will report lower child emotional overeating than the control group, and that this effect is mediated by mothers’ use of food to soothe. Based on previous data that infant negativity impacts mothers’ use of food to soothe,21 an exploratory aim of this study was to examine whether this process varied by infant negative affect.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Study design and participants

Details of the INSIGHT RCT study design, recruitment, and CONSORT diagram have been published elsewhere.18 This study was approved by the Human Subjects Protection Office of the Penn State College of Medicine’s Human Subjects Protection Office and registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov prior to participant enrollment (Registry number: NCT01167270; registered 21 July 2010). Mothers and their newborns were recruited from one maternity ward in central Pennsylvania between January 2012 and March 2014. Mothers were eligible to participate in the study if they were primiparous, English-speaking and ≥20 years of age, and if their newborns were full-term (≥37 weeks gestation), singleton and had a birth weight of ≥2500 g. Mother-infant dyads were randomized to a RP intervention or a home safety control group using a computer-generated algorithm, stratified by birth weight for gestational age (<50th percentile or ≥50th percentile) and intended feeding mode (breastfeeding or formula). Following randomization at infant age 2 weeks, intervention materials were mailed to all participants.18 Research nurses administered both the RP and control interventions at home visits conducted at child age 3 to 4, 16, 28, and 40 weeks and at research center visits at 1 and 2 years. Of the 279 mother-infant dyads who completed the 3 to 4 week visit, 243 remained in the study by 2 years. The sample for the current analysis is 207, as 36 participants had missing data on one or more of the following: emotional overeating (n = 27), food to soothe (n = 19), and/or negative affect (n = 9). Mothers included in the current analysis were more likely to be older (29.5 vs 26.3 years, P < .0001), married (82% vs 57%, P < .0001), White (95% vs 74%, P < .0001), have a higher income (82% vs 45% earned ≥$50 000, P = .03) and have a college/university education (73% vs 33%, P < .0001) compared to those who had missing data on the present variables of interest or had dropped out before child age 2 years.

2.2 |. Responsive parenting intervention

A detailed description of the INSIGHT curriculum has been published.18 Briefly, the nurses delivered the RP intervention content to mothers which centered around anticipatory guidance for managing four infant behavioral states: sleeping, fussy, alert and calm, and drowsy. RP guidance for infant fussing included teaching mothers to identify hunger and distinguish hunger from other sources of infant distress. To provide mothers with alternative strategies to feeding to calm their infants, mothers were provided with an educational video, The Happiest Baby on the Block,22 in the weeks following delivery. At the first home visit, the nurses demonstrated these calming strategies to soothe a non-hungry infant (eg, swaddling, swinging, or offering a pacifier). Content related to using alternatives to food to soothe child distress was discussed at each home visit to promote the child’s development of self-regulation and capacity to self-soothe. At child age 1 year, mothers were provided with an age-appropriate video, The Happiest Toddler on the Block,23 to support mothers in managing child tantrums. Mothers in the control group received an intervention of comparable intensity delivered by the same research nurses but focused on home safety (including food safety and choking prevention) within the framework of the four infant behavioral states. The home safety visits were designed as an “attention control” such that the two study groups received distinct, non-overlapping interventions of equal intensity. Implementation fidelity was routinely assessed throughout the intervention.20 Adherence to message delivery was documented at every home visit by participating mothers indicating the topics addressed during each home visit on an evaluation form. Similarly, research nurses completed a self-report checklist of intervention messages delivered in each visit. Research nurses also audio-recorded the home visits every 6 months, after obtaining verbal consent from the participant to record the session. These recordings were monitored by project staff who provided ongoing coaching and supervision to the research nurses in a report.

2.3 |. Measures

2.3.1 |. Sociodemographic characteristics

Data were collected online and managed using REDCap.24 Paper surveys were mailed to participants without Internet connectivity (n = 20). Participants provided demographic information at enrollment (eg, maternal race/ethnicity, marital status, annual household income, and highest educational attainment). Maternal age, pre-pregnancy weight and height, and infant gestational age, sex, and birth weight were extracted from medical charts. At child age 28 weeks, mothers reported on their frequency of breast and formula feeding. Predominant breastfeeding was defined if ≥80% of milk feedings were breastmilk, either at the breast or bottle. Researchers measured child weight and height/length at 1, 2, and 3 year clinic visits. Anthropo-metric measures were converted to age- and sex-adjusted body mass index (BMI) z scores based on the World Health Organization growth standards25 before child age 2 years, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth26 for children 2 years and older.

2.3.2 |. Mothers’ use of food to soothe

Mothers self-reported their use of food to soothe child distress using 12 items from a modified version of the Baby’s Basic Needs Questionnaire27 at child age 18 months. These items were previously used to evaluate INSIGHT intervention effects at child age 8, 16, 32, and 44 weeks.17 Mothers rated how often they used food to soothe child distress across a variety of situations, regardless if hunger was the source of infant distress, on a 5-point Likert scale with responses anchored from never (1) to always (5). This time-point was selected because age 18 months represents a developmental period when toddlers are becoming increasingly autonomous,28 acquiring emotion regulation skills,29 and are likely to be offered table foods that the parents are consuming.30 Items were averaged to create an overall score with higher scores indicating mothers’ greater use of food to soothe (α = .85). The food to soothe scale can also be divided into two factors: contextual-based (six items: α = .74) and emotion-based (six items: α = .88) food to soothe. Contextual-based food to soothe assesses the frequency of mothers’ use of food to quiet, distract or manage a distressed child in a variety of dayto-day situations (eg, in the car or shopping). Emotion-based food to soothe assesses the frequency of mothers’ feeding children in response to child distress or maternal emotions (eg, stress, frustration, or anger).

2.3.3 |. Child emotional overeating

The Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ),31 a 35 item validated parent-report measure, was assessed at child age 30 months. The emotional overeating subscale is used in the current analysis to measure mothers’ perceptions of child emotional overeating. Mothers reported if their child ate more when worried, annoyed, anxious or has nothing else to do (four items). Items were scored from never (1) to always (5) and averaged, with higher scores indicating children’s greater tendency to emotionally overeat (α = .72).

2.3.4 |. Temperament

The Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ—Revised)—Very Short Form15 was assessed at infant age 16 weeks. The negative affectivity super-factor is examined in the current study (12 items; α = .81). Mothers also completed three subscales of the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (ECBQ)32 at age 2 years: frustration (12 items; α = .82), inhibitory control (12 items; α = .87) and soothability (nine items; α = .82). Items in both temperament measures were scored from never (1) to always (7) and averaged within each subscale/super-factor. Higher scores indicated higher levels of that temperament dimension. The earliest measure of infant temperament (age 16 weeks) was used to address the exploratory research aim, while the early childhood measure (age 2 years) is included for descriptive purposes.

2.4 |. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Statistical significance was defined as P < .05, and all inferential tests were two-sided. Sociodemographics and the main variables of interest were compared by study group using independent samples t tests and χ2 tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

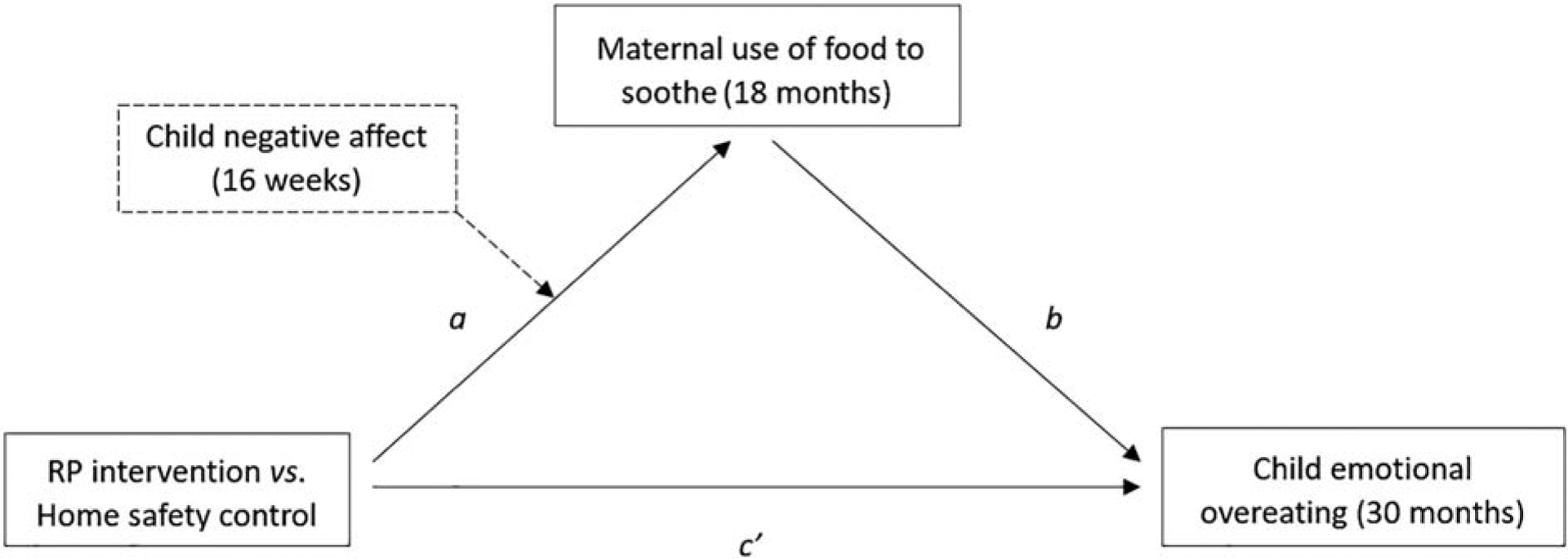

Mediation analysis was used to examine if mothers’ use of food to soothe explained study group effects on child emotional overeating. Mediation analysis was planned if the following criteria were met: the mediator (food to soothe) was significantly associated with both the independent variable (study group; Figure 1, a pathway) and the outcome variable (emotional overeating), controlling for the independent variable (study group; Figure 1, b pathway) in separate multivariate linear regressions, adjusting for covariates. We planned to include participant sociodemographic characteristics in the model as covariates if they were significantly associated with maternal use of food to soothe and child emotional overeating. The SAS PROCESS macro33 was used to analyze whether food to soothe mediated the association between study group and child emotional overeating (model 4). Bias-corrected bootstrapping Confidence Intervals (CI) at the 95% level were used for 10 000 resamples to establish direct (c′) and indirect (ab) effects. Mediation was established if the indirect effect’s CI did not include “0”.33 In the case of significant overall effects, dimensions of food to soothe (ie, contextual- and emotion-based food to soothe) will be probed further.

FIGURE 1.

Model specification for mediation of the INSIGHT RP intervention on child emotional overeating through maternal food to soothe, moderated by infant negative affect.

Maternal use of food to soothe from the Baby’s Basic Needs Questionnaire27; Child emotional overeating from the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire31; Negative affect from the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (Revised)—Very Short Form.15 Solid lines denote the pathways for the main mediation analysis; the dotted lines indicate the exploratory, moderated mediation analysis. INSIGHT, intervention nurses start infants growing on healthy trajectories; RP, responsive parenting

A conditional process analysis was used to explore whether early infant negative affect altered the study group effect on maternal food to soothe, which, in turn, may influence intervention effects on child emotional overeating. This corresponds to moderation of the “a” pathway in Figure 1 or “action theory”.34 Infant negative affect was entered into the conditional process model in the SAS PROCESS macro.33 Moderated mediation was established if the index of moderated mediation’s bias-corrected bootstrapping CI did not include “0”.33

Multiple imputation (Markov chain Monte Carlo) was used to account for missing values and confirm the results in the full sample of participants who remained active in the study at age 2 years (n = 243). Information on maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, marital status, age at recruitment, education, study group and use of food to soothe (18 months); and child sex, gestational age, birth weight, negative affect (16 weeks) and emotional overeating (30 months) were used to estimate imputations. Analyses examining study group effects on the main variables of interest and the mediation analyses were based on pooled results of nine imputed data sets. Similar results were found using the imputed data sets (except where indicated), and therefore results are reported for the complete cases (n = 207).

3 |. RESULTS

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mothers were primiparous, predominantly white, non-Hispanic, married, and college educated with the majority of mothers reporting annual household incomes ≥$50 000. Maternal and child sociodemographic characteristics, and child frustration, inhibitory control and soothability, did not differ by study group.

TABLE 1.

INSIGHT child and maternal sociodemographic characteristics by study group

| RP intervention (n = 105) | Control (n = 102) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Male sex, N (%) | 54 (51) | 51 (50) | .84 |

| Gestational age (wk), mean (SD) | 39.5 (1.3) | 39.5 (1.2) | .82 |

| Birth weight (kg), mean (SD) | 3.42 (0.45) | 3.46 (0.42) | .52 |

| Predominantly breastfed at 6 mo, N (%) | 39 (37.1) | 36 (17.4) | .78 |

| Temperament at 24 mo, mean (SD) | |||

| Frustration | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.8) | .08 |

| Inhibition | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.8) | .89 |

| Soothability | 5.5 (0.7) | 5.4 (0.6) | .27 |

| Mother | |||

| Age (y) at recruitment, mean (SD) | 29.4 (4.2) | 29.6 (4.8) | .77 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, mean (SD) | 25.6 (5.0) | 25.6 (5.2) | .97 |

| White, N (%) | 98 (93.3) | 98 (96.1) | .38 |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 6(2.9) | 5 (2.4) | .78 |

| Married, N (%) | 85 (81) | 84 (82) | .79 |

| Annual household income, N (%) | .30 | ||

| ≤$24 999 | 7 (6.7) | 7(6.9) | |

| $25 000-$49 999 | 2 (1.9) | 15 (14.7) | |

| $50 000-$99 999 | 67 (63.8) | 38 (37.3) | |

| $100 000 or more | 27 (25.7) | 38 (37.3) | |

| Do not know or refuse to answer | 2 (1.9) | 4(3.9) | |

| Education, N (%) | .84 | ||

| High school graduate or less | 7 (6.7) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Some college | 23 (21.9) | 19 (18.6) | |

| College graduate | 43 (41.0) | 47 (46.1) | |

| Graduate degree + | 32 (30.5) | 28 (27.5) | |

Note: Child temperament measured using the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire.32

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; INSIGHT, intervention nurses start infants growing on healthy trajectories; RP, responsive parenting.

Pearson correlations showed no association between child BMI z scores at ages 1, 2, and 3 years and child emotional overeating (Ps > .11). Child frustration (r = 0.31, P < .0001), inhibitory control (r = −0.26, P = .0002) and soothability (r = −0.26, P = .0002) at 2 years was associated with child emotional overeating at 30 months. Infant negative affect at 16 weeks was not associated with mothers’ use of food to soothe at 18 months (r = 0.12, P = .08), but was positively associated with child emotional overeating at 30 months (r = 0.26, P < .001). Mothers’ use of food to soothe at 18 months was positively associated with child emotional overeating at 30 months (r = 0.36, P < .0001).

Compared to the control group (n = 102), mothers who received the RP intervention (n = 105) reported using less food to soothe at child age 18 months [M (SE) = 1.81 (0.06) vs 1.58 (0.05), P = .002, d = 0.44] and perceived their child to be lower in emotional overeating at age 30 months [1.47 (0.05) vs 1.35 (0.04), P = .046, d = 0.27]. Compared to the control group, mothers who received the RP intervention also perceived their infant to have lower negative affect at age 16 weeks [3.53 (0.09) vs 3.26 (0.09), P = .04, d = 0.30]. However, the effect of study group on infant negative affect did not reach significance in the imputed dataset [3.47 (0.08) vs 3.26 (0.08), P = .053, d = 0.25], reflecting trend-level data previously reported in the full INSIGHT sample.35

3.1 |. Mediation analyses

Mothers’ use of food to soothe met the criteria for mediation and was examined as a mediator of study group effects on child emotional overeating. No sociodemographic covariates were associated with both mothers’ use of food to soothe and child emotional overeating. The unstandardized path coefficients and standard errors for the mediation model of study group on child emotional overeating through maternal use of food to soothe are shown in Table 2. There was a significant indirect effect (ab) of study group on child emotional overeating through maternal use of food to soothe [B(SE) = −0.06 (0.03), 95% CI: −0.12 to −0.02]. The mediation model explained 13% of the variance in mothers’ perceptions of child emotional overeating at age 30 months. Mediation models for contextual- and emotion-based food to soothe yielded similar results (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Estimated path coefficients for the mediation model of the INSIGHT RP intervention on child emotional overeating through mothers’ use of food to soothe (n = 207)

| Consequent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal food to soothe (“a” pathway) | Child emotional overeating (“b” pathway) | |||||||

| Antecedent | B | SE | P value | B | SE | P value | ||

| Study group (Home safety control vs RP intervention) | a | −0.22 | 0.07 | .002 | c′ | −0.06 | 0.06 | .32 |

| Maternal food to soothe | – | – | – | b | 0.29 | 0.06 | <.0001 | |

| Constant | i | 1.81 | 0.05 | <.001 | i2 | 0.95 | 0.11 | <.0001 |

| R2 = 0.04 | R2 = 0.13 | |||||||

| F(1,205) = 9.52, P = .002 | F(2,204) = 15.71, P < .0001 | |||||||

Note: Maternal food to soothe at child age 18 months assessed via the Baby’s Basic Needs Questionnaire,27 child emotional overeating at age 30 months via the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire.31 Study group is dummy coded such that safety control = 0; and RP intervention = 1.

Abbreviations: INSIGHT, intervention nurses start infants growing on healthy trajectories; RP, responsive parenting.

Next, we tested whether the indirect effect of study group on child emotional overeating through mothers’ use of food to soothe varied by infant negative affect using moderated mediation. The index of moderated mediation indicated that the indirect effect was not moderated by infant negative affect [B (SE) = 0.02 (0.02), 95% CI: −0.03 to 0.07]. In other words, the intervention effect on child emotional overeating through mothers’ use of food to soothe occurred independent of child temperament. The indirect effect of study group on child emotional overeating through mothers’ use of food to soothe also occurred independent of child sex (data not shown). We reran the mediation and moderated mediation analyses, replacing mothers’ use of food to soothe measured at 18 months with earlier measures (infant age 8, 16, 32, and 44 weeks). Results were similar, with the exception of mothers’ use of food to soothe at infant age 8 weeks, where the indirect effect was not significant (data not shown).

4 |. DISCUSSION

We extend the knowledge of emotional overeating aetiology within the context of a randomized obesity prevention intervention focused on RP. Mothers who received a RP intervention that began during the early postpartum period reported using less food to soothe child distress at child age 18 months compared to a home safety control group, indicating maintenance in study group differences from infancy17 to toddlerhood. Further, mediation analyses supported the hypothesis that mothers’ use of food to soothe child distress could be one mechanism driving the development of emotional overeating. Mothers’ less frequent use of food to soothe appears to explain the RP intervention effect on decreased child emotional overeating at 30 months, regardless of negative affect during infancy. However, emotional overeating at 30 months was not associated with child weight up to age 3 years.

Aparicio et al5 propose that emotional overeating, as a function of maladaptive emotion regulation, may be one pathway that links stress to child obesity. Results from the current study show that indicators of child self-regulation (ie, lower inhibitory control, capacity to self-soothe, and tolerance for frustration) were inversely associated with child emotional overeating. This is consistent with findings in older children. Emotional and behavioral problems in 3 year old Dutch children predicted increasing trajectories of emotional overeating from the ages of 4 to 10 years.36 In the same cohort, Derks et al4 showed that emotional overeating was both a predictor and consequence of higher weight status from 4 to 10 years, yet these factors were not cross-sectionally associated at 4 years. Associations between emotional overeating and weight may be age-dependent, emerging with children’s increasing autonomy and access to foods4 or adiposity rebound.14 This may explain our non-significant association between emotional overeating and weight status in younger children. Future research should examine these associations prospectively in the INSIGHT study, or in trials with school-aged children or adolescents to further understand whether and how the modification of emotional overeating can impact weight status.

Current findings provide further support for emotional overeating as a learned and therefore modifiable behavior, corroborating findings from heritability analyses2,7,8 and another obesity prevention intervention.37 Two British twin cohort studies show that 71 to 93% of variability in emotional overeating is explained by the “shared home environment”.2,7 As architects of their child’s home environment, parents are therefore appropriate targets for intervention. The NOURISH RCT37 reported that mothers who received a responsive feeding intervention perceived their 2 year old child to be lower in emotional overeating than the “standard care” control group at 6 months post-intervention. Like the current study, small effects on emotional overeating were reported (d = 0.24).37 However, the intervention effect on emotional overeating in NOURISH did not persist to child age 5 years (P = .09).38 While both shared a similar focus on responsive feeding practices, INSIGHT took on a broader approach to RP across infant behavioral states and was implemented earlier in infancy compared to NOURISH (3–4 weeks old vs 4–7 months old). Examining whether the INSIGHT RP intervention effects on child emotional overeating are sustained later in child development will further the understanding of how and when to ideally modify emotional eating trajectories.

The INSIGHT intervention effects on mothers’ self-reported use of food to soothe child distress previously reported17 persisted into toddlerhood. Toddlerhood is a particularly sensitive period in which children acquire skills to regulate their own emotions through interactions with the social environment.29 Concurrently, this period may also represent a time in which children’s ability to compensate for variations in energy density (ie, appetite self-regulation) may diminish.39 Parents are therefore critical in scaffolding children’s appropriate responses to both emotions and appetite. While feeding may temporarily suppress children’s distress by activating the reward system,40 feeding for reasons unrelated to hunger may undermine children’s appetite self-regulation or encourage them to adopt maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. In an experimental study, children of parents who reported using food as a tool to control their behavior during the preschool years (3–5 years old) ate more in the absence of hunger under a stress-induced condition 2 years later.41 Our current study shows that anticipatory RP guidance decreases mothers’ use of food to soothe child distress, which in turn, may reduce children’s tendency to eat in response to stressors.

Individual children differ in their clarity of expressing cues, making RP guidance (and therefore, avoiding feeding to soothe) easier or more difficult to follow depending on child characteristics.42 For example, mothers of children who exhibit greater negative affect may respond to aversive emotions by feeding to quickly soothe an upset child.27 Differential susceptibility theory43 posits that children with certain behavioural predispositions (ie, negativity) may be more sensitive to changes in their environment, suggesting that those intervention group children with high levels of negativity might benefit the most from an intervention like INSIGHT.44 However, when focusing on the present outcomes of interest, findings suggest that an RP intervention can reduce child emotional overeating through mothers’ decreased use of food to soothe child distress, regardless of early infant negative affect. Similar to our prior findings of main effects on child self-regulation,44 these results suggest that the RP intervention’s effects on feeding to soothe and child emotional overeating are robust across levels of infant negative affect. While these findings are encouraging in terms of the generalizability of the RP intervention’s effects in these areas, it is important to note that we were unable to assess negativity earlier than age 16 weeks. At 16 weeks, there is some evidence to suggest that the experience of being in the RP intervention group was already starting to affect mothers’ perceptions of their child’s negativity.35 Although not statistically significant, mothers in the RP intervention group reported their child to be lower in negativity compared to the control group (3.3 vs 3.5, P < .10). Ideally, moderated mediation performed in the current analysis would have used an earlier, “purer” measure of negative affect, however, this was not possible.

Other limitations of the present study include the use of mother reports of both maternal feeding to soothe and child emotional overeating. While mother-reported measures allow representation of behaviors over a period of time, they may be subject to social desirability bias, including higher reporting of behaviours encouraged by the RP intervention in the RP group. Common methods of parent-report may also have resulted in inflated associations (ie, shared method variance). Further, given the complex nature of parent-child interactions, there may be additional mediators involved in the aetiology of child emotional overeating which are not explored in the current study. For example, future research could examine the role of maternal eating behaviours, including mothers’ own emotional overeating, on the development of child emotional overeating. Both interventions were delivered by the same research nurses to eliminate any potential biases introduced by nurse characteristics. While contamination between the RP intervention and the home safety control group is a possibility, the research nurses followed a strict curriculum with routine fidelity assessment to prevent intervention drift. The observed effects on primary and secondary outcomes17,19,20 and fidelity results20 suggest that this possibility did not preclude the implementation of an effective RP intervention. Lastly, the sample was relatively homogenous, consisting of predominantly white, middle-income, well-educated and English-speaking primiparous mothers, limiting the generalizability of findings.

There were several strengths to the current analysis. The mediation analysis undertaken is novel and responds directly to recent calls for understanding pathways involved in nutrition-related outcomes.45 The analysis reveals not only mechanisms underlying child health outcomes, but how to intervene in these processes. The mediation model examined was grounded within a strong theoretical framework5 and also informed by empirical observational findings in older children.16 We found consistent indirect effects of study group on child emotional overeating through mothers’ use of food to soothe at infant age 16, 32, and 44 weeks, affirming the mechanism examined during toddlerhood. Current findings provide further support for the efficacy of the INSIGHT RP intervention.17,19,20

Our results suggest that the development of child emotional overeating can be modified in the context of an early life obesity prevention intervention. Parents appear to play an important role in the etiological pathway of emotional overeating through how they respond to children’s distress. Using food to soothe child distress may teach children that negative emotions can be suppressed through the pleasant effects of eating, thus reinforcing emotional overeating. Guiding parents to use alternative methods to soothe their child’s distress rather than feeding could ultimately reduce the expression of emotional overeating in early childhood. This causal evidence supporting RP as a predictor of these outcomes can inform future study designs aiming to prevent emotional overeating and attendant effects on poor diet and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK088244); National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000127); the Children’s Miracle Network at Penn State Children’s Hospital; US Department of Agriculture (2011-67001-30117), which supported graduate students; and the Pennsylvania State University Clinical and Translational Science Award from the Penn State Clinical and Translational Research Institute, which supported research electronic data capture. The authors acknowledge Jessica Beiler, MPH, Jennifer Stokes, RN, Patricia Carper, RN, Heather Stokes, Susan Rzucidlo, MSN, RN, Lindsey Hess, MS, and Eric Loken, PhD, for their assistance with this project. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Funding information

Children’s Miracle Network at Penn State Children’s Hospital; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant/Award Number: UL1TR000127; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Number: R01DK088244; Penn State Clinical and Translational Research Institute, Pennsylvania State University Clinical and Translational Research Institute; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Grant/Award Number: 2011-67001-30117

Abbreviations:

- BMI

body mass index

- INSIGHT

intervention nurses start infants growing on healthy trajectories

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

- RP

responsive parenting

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest was declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macht M How emotions affect eating: a five-way model. Appetite. 2008;50:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herle M, Fildes A, Rijsdijk F, Steinsbekk S, Llewellyn C. The home environment shapes emotional eating. Child Dev. 2018;89:1423–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jalo E, Konttinen H, Vepsäläinen H, et al. Emotional eating, health behaviours, and obesity in children: a 12-country cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2019;11:351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derks IP, Sijbrands EJ, Wake M, et al. Eating behavior and body composition across childhood: a prospective cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aparicio E, Canals J, Arija V, De Henauw S, Michels N. The role of emotion regulation in childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment. Nutr Res Rev. 2016;29:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freitas A, Albuquerque G, Silva C, Oliveira A. Appetite-related eating behaviours: an overview of assessment methods, determinants and effects on children’s weight. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;73: 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herle M, Fildes A, Llewellyn CH. Emotional eating is learned not inherited in children, regardless of obesity risk. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13: 628–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herle M, Fildes A, Steinsbekk S, Rijsdijk F, Llewellyn CH. Emotional over- and under-eating in early childhood are learned not inherited. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan HI, Kaplan HS. The psychosomatic concept of obesity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1957;125:181–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Boom DC. The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: an experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Dev. 1994;65:1457–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anzman-Frasca S, Liu S, Gates KM, Paul IM, Rovine MJ, Birch LL. Infants’ transitions out of a fussing/crying state are modifiable and are related to weight status. Inf Dent. 2013;18:662–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stifter CA, Moding KJ. Understanding and measuring parent use of food to soothe infant and toddler distress: a longitudinal study from 6 to 18 months of age. Appetite. 2015;95:188–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chong SY, Chittleborough CR, Gregory T, Lynch JW, Mittinty MN, Smithers LG. Associations of parental food-choice control and use of food to soothe with adiposity in childhood and adolescence. Appetite. 2017;113:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen PW, Derks IPM, Batenburg A, et al. Using food to soothe in infancy is prospectively associated with childhood BMI in a population-based cohort. J Nutr. 2019;149:788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putnam SP, Helbig AL, Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK, Leerkes E. Development and assessment of short and very short forms of the infant behavior questionnaire-revised. J Pers Assess. 2014;96: 445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinsbekk S, Barker ED, Llewellyn C, Fildes A, Wichstrom L. Emotional feeding and emotional eating: reciprocal processes and the influence of negative affectivity. Child Dev. 2018;89:1234–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savage JS, Hohman EE, Marini ME, Shelly A, Paul IM, Birch LL. INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention and infant feeding practices: randomized clinical trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018; 15:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul IM, Williams JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. The intervention nurses start infants growing on healthy trajectories (INSIGHT) study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage JS, Birch LL, Marini M, Anzman-Frasca S, Paul IM. Effect of the INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention on rapid infant weight gain and overweight status at age 1 year: a randomized clinical. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:742–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. Effect of a responsive parenting educational intervention on childhood weight outcomes at 3 years of age: the INSIGHT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018; 320:461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stifter CA, Moding KJ. Infant temperament and parent use of food to soothe predict change in weight-for-length across infancy: early risk factors for childhood obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42:1631–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karp H, Montee N. The Happiest Baby on the Block: The New Way to Calm Crying and Help Your Baby Sleep Longer. Los Angeles: Happiest Baby, Inc. 2006, 128 minutes. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karp H, Montee N. The Happiest Toddler on the Block. Los Angeles: Happiest Baby, Inc. 2004, 69 minutes. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stifter CA, Anzman-Frasca S, Birch LL, Voegtline K. Parent use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress and child weight status. An exploratory study. Appetite. 2011;57:693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brownell CA, Kopp CB. Socioemotional Development in the Toddler Years: Transitions and Transformations. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeman J, Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, Stegall S. Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27: 155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birch LL, Doub AE. Learning to eat: birth to age 2 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:723S–728S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, Rapoport L. Development of the Children’s eating behaviour questionnaire. J Child Psych Psychiatry. 2001;42:963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: the early childhood behavior questionnaire. Infant Behav Dev. 2006;29:386–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd. ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prev Sci. 2009;10:87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anzman-Frasca S, Paul IM, Moding KJ, Savage JS, Hohman EE, Birch LL. Effects of the INSIGHT obesity preventive intervention on reported and observed infant temperament. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2018;39:736–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derks IPM, Bolhuis K, Sijbrands EJG, Gaillard R, Hillegers MHJ, Jansen PW. Predictors and patterns of eating behaviors across childhood: results from the generation R study. Appetite. 2019;141: 104295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Battistutta D, et al. Child eating behavior outcomes of an early feeding intervention to reduce risk indicators for child obesity: the NOURISH RCT. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22: E104–E111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magarey A, Mauch C, Mallan K, et al. Child dietary and eating behavior outcomes up to 3.5 years after an early feeding intervention: the NOURISH RCT. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:1537–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brugaillères P, Issanchou S, Nicklaus S, Chabanet C, Schwartz C. Caloric compensation in infants: developmental changes around the age of 1 year and associations with anthropometric measurements up to 2 years. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109:1344–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erlanson-Albertsson C How palatable food disrupts appetite regulation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;97:61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrow CV, Haycraft E, Blissett JM. Teaching our children when to eat: how parental feeding practices inform the development of emotional eating—a longitudinal experimental design. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:908–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buvinger E, Rosenblum K, Miller AL, Kaciroti NA, Lumeng JC. Observed infant food cue responsivity: associations with maternal report of infant eating behavior, breastfeeding, and infant weight gain. Appetite. 2017;112:219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:300–304. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anzman-Frasca S, Stifter CA, Paul IM, Birch LL. Negative temperament as a moderator of intervention effects in infancy: testing a differential susceptibility model. Prev Sci. 2014;15:643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDaniel HL, Fairchild AJ. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: mediation analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105:1259–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]