Abstract

Objectives:

This study investigated the correlation between homocysteine levels in patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome and GRACE Score.

Methods:

This study included 191 cases -140 Non-ST MI cases and 51 MI with ST-elevation cases in Şişli Etfal Training and Research Hospital Coronary Intensive Care Unit between December 2008 and March 2010. Homocysteine was measured by immulite 2000 device, using kemiluminesans method and competitive immunoassay principle and a kit by DPC was used during the measurement. The reference range given by the producing company was between 5-15 Mmol/L for male and female adults. The patients were classified into three risk groups as low, medium and high on the basis of the criteria identified in GRACE risk score: age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, serum creatine levels, Killip classification, cardiac arrest on admission, increased cardiac enzymes and ST segment depression. The relation between homocysteine levels in patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome and GRACE risk score was evaluated.

Results:

In the Non-ST MI group, a statistically-moderate positive correlation was seen between homocysteine and GRACE risk score during the study (p<0.05). However, in the MI with ST-elevation group, no correlation was found between homocysteine and GRACE risk score (p>0.05). Overall, despite the low figures, a meaningful positive relation was observed between homocysteine and GRACE risk score in all cases.

Conclusion:

Homocysteine is independent of other classic risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, we believe that routine plasma homocysteine levels should be checked when evaluating risk factors for Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery disease.

Keywords: Coronary syndrome, homocysteine, grace

Acute Coronary Syndrome is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity in adults. It is claimed that there were 6.3 million deaths due to this syndrome, which made up 28.9% of the total deaths worldwide. By 2020, the figure is expected to rise to 36.3.[1] In this study, TEKHARF (Turkish Adults Coronary Risk Factors Study) was conducted by Turkish Society of Cardiology. The findings showed that overall annual death rate from coronary heart disease was 5.2 per 1000 person (3.2 in females). Looking at the causes of total mortality rates, it can be observed that the highest rate belonged to a coronary heart disease with 42.5.[2]

Measures have been considered to prevent cardiovascular diseases, which are listed as the top cause of mortality, and the risk factors have been determined. Framingham Heart Study[3] has played a central role in identifying the common risk factors for heart disease, which are age, cigarette smoking, gene, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. However, these traditional factors alone do not fully explain the prevalence of coronary artery disease and the development of premature coronary artery disease. For instance, nearly half of the patients with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina do not have classic risk factors.[4] Currently, new types of atherosclerotic risk factors, such as elevated homocysteine levels, are being taken into consideration.

Homocysteine is the sulfur-containing amino acid formed during the metabolism of methionine. Hyperhomocysteinemia may arise from various nutritional and genetic factors. Elevated plasma homocysteine level is an independent risk factor for peripheral vascular, cerebrovascular disease, as well as coronary heart disease.[5] Homocysteine inhibits the proliferation of endothelial cells, and many in vitro studies have shown that incorporation of homocysteine into cell culture has led to endothelial cell damage.[6]

Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome represent a heterogeneous population and significant differences exist in their early and late complications and prognosis. Early risk score is highly important to develop treatment strategies. There are patients with a good prognosis, who respond to suitable treatment regimes, as well as patients with risk of mortality and MI in need of coronary intensive care. Therefore, the risk score plays a central role in the decision pathway for the assessing and managing such patients.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the correlation between the homocysteine levels of patients with acute coronary syndrome and GRACE risk score.

Methods

This study included 191 cases -140 NonST MI cases and 51 MI with ST-elevation cases in Şişli Etfal Training and Research Hospital Coronary Intensive Care Unit between December 2008 and March 2010. We obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee for this study.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: illnesses or situations which may influence homocysteine levels; hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, renal failure, rheumatoid arthritis, Behçet disease, malignancy, vegetarianism, B12 deficiency, folic acid deficiency, chronic alcohol use, use of anticonvulsant, oral contraceptives, hormonal therapy, vitamin intake, acetylcysteine, penicillamine, methotrexate, L-dopa, cholestyramine, nitric oxide anesthesia which may influence homocysteine levels.

For each patient, documentation of demographic data and medical history was recorded, and GRACE risk scores were calculated. Additionally, homocysteine levels were determined. Demographic characteristics were as follows:1- Gender 2- Risk factors; diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoking 3- Medical history; MI, myocardial revascularization (PCI, CABG, SKZ, peripheral arterial disease, transient ischemic attack, stroke) 4- Drugs used by the patient before the application; platelet inhibitors, aspirin, beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor, ARB, statin 5- Cardiac markers; blood CK-MB, Troponın-I values were measured.

Fasting blood glucose, urea, creatinine, total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, FT3, FT4, TSH, folic acid, vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels of each patient were measured after overnight fasting.

Homocysteine Measurement: Homocysteine was measured by immulite 2000 device, using kemiluminesans method and competitive immunoassay principle and a kit by DPC was used during the measurement. The reference range given by the producing company was between 5-15 Mmol/L for male and female adults.

The GRACE risk score was calculated by the eight different baseline variables incorporated in the risk calculator; age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, serum creatinine levels, cardiac arrest at admission, ST-segment deviation on ECG, elevated c Tn and congestive heart failure (Killip class).[11] According to the GRACE risk score, patients were classified into three risk groups for in-hospital mortality. This implies low (<108), intermediate (109-140) and high risk (>140). The relation between the homocysteine levels of patients with acute coronary syndrome and GRACE risk score was evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007&PASS (Power Analysis and Sample Size) 2008 Statistical Software (Utah, USA) programs were used. While evaluating the data of this study, a student t-test was used to compare descriptive statistical methods (Average, standard deviation, frequency), as well as quantitative data. Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative data. Level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

This study included 191 cases -140 Non-ST MI cases and 51 MI with ST-elevation cases in Şişli Etfal Training and Research Hospital Coronary Intensive Care Unit between December 2008 and March 2010. Ages of patients varied between 26 and 87. Mean age of cases in this study was that 61.1±13.97.127 patients are male and 64 patients are female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of age and gender in both groups

| Non ST MI (n=140) Mean±SD | ST Elevation MI (n=51) Mean±SD | Total | ap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 62.14±14.48 | 58.29±12.16 | 61.1±13.97 | 0.070 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | bp | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 83 (59.3) | 44 (86.3) | 127 (66.5) | 0.001** |

| Female | 57 (40.7) | 7 (13.7) | 64 (33.5) | |

Student t test

p<0.05;

chi-square test

p<0.01.

The rate of patients with diabetes and hypertension were higher in non-ST MI groups. In the ST-elevation MI group, the number of smokers was higher. There was no difference between the rates of hyperlipidemia in the groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the risk factors in both groups

| Non ST MI (n=140) Mean±SD | ST Elevation MI (n=51) Mean±SD | Total Mean±SD | bp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 44 (31.4) | 8 (15.7) | 52 (27.2) | 0.031* |

| Hyperlipidemia | 80 (57.1) | 32 (62.7) | 112 (58.6) | 0.487 |

| Hypertension | 82 (58.6) | 16 (31.4) | 98 (51.3) | 0.001** |

| Smoking | 80 (57.1) | 40 (78.4) | 120 (62.8) | 0.007** |

Student t test

p<0.05;

chi-square test

p<0.01.

The number of patients with a history of MI and CABG was higher in non-ST MI groups. There was no difference between history of myocardial revascularization as PCI and SKZ/TPA in both groups. There was no difference between the history of PAH and CVE in the groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distributions of the CVD-related history in both groups

| Non ST MI (n=140) n (%) | ST Elevation MI (n=51) n (%) | Total n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI | 27 (19.3) | 2 (3.9) | 29 (15.2) | 0.009** |

| Myocardial revascularization | ||||

| PCI | 14 (10) | 2 (3.9) | 16 (8.4) | 0.180 |

| CABG | 12 (8.6) | 0 | 12 (6.3) | 0.031* |

| SKZ/TPA | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| PAD | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.464 |

| CVE | 16 (11.4) | 3 (5.9) | 19 (9.9) | 0.257 |

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

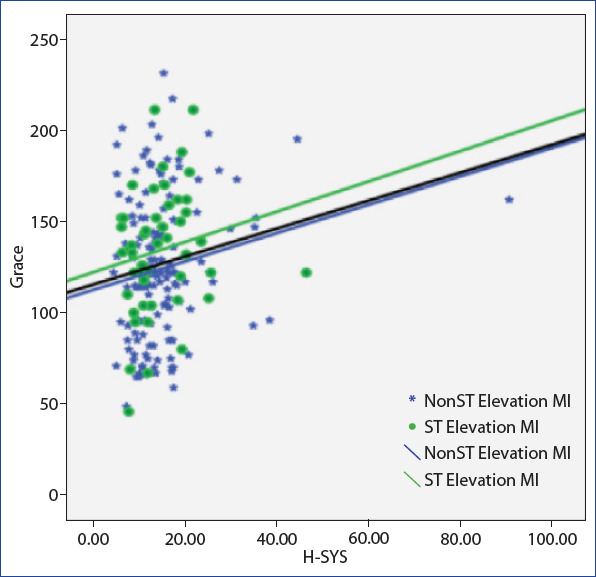

Evaluating all the cases, a modestly significant relationship can be seen between the levels of homocysteine and GRACE risk score (p<0.05). In non-ST MI group, a modestly significant relationship can also be seen between homocysteine and GRACE risk score (p<0.05), whereas no significant relationship can be detected between homocysteine and GRACE risk score in ST MI group (p>0.05) (Tables 4-6, Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Drug use in both groups

| Non ST MI (n=140) n (%) | ST ElevationMI (n=51) n (%) | Total n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet Inhibitors | 8 (5.7) | 2 (3.9) | 10 (5.2) |

| ASA | 34 (24.3) | 4 (7.8) | 38 (19.9) |

| Beta Blockers | 17 (12.1) | 2 (3.9) | 19 (9.9) |

| Calsiumchannel blockers | 17 (12.1) | 4 (7.8) | 21 (11) |

| ACE inhibitors/ARB | 42 (30) | 6 (11.8) | 48 (25.1) |

| Statin | 21 (15) | 2 (3.9) | 23 (12) |

Table 6.

Relation between level of homocysteine and Grace risk scores in the groups

| H-SYS-GRACE Risk Score Relation | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Total (n=191) | 0.175 | 0.016* |

| Non ST MI (n=140) | 0.182 | 0.031* |

| ST ElevationMI (n=51) | 0.173 | 0.225 |

Figure 1.

Homocysteine and grace risk score relation.

Table 5.

The levels of the homocysteine and grace risk scores of patients in the both groups

| Non ST MI (n=140) Mean±SD | ST Elevation MI (n=51) Mean±SD | Total Mean±SD | ap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-SYS (mol/L) | 15.12±9.06 | 14.40±6.82 | 14.92±8.51 | 0.606 |

| GRACE Risk Score | 124.29±39.57 | 134.12±33.48 | 126.91±38.21 | 0.116 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | bp | |

| H-SYS (mol/L) | ||||

| Normal | 86 (61.4) | 30 (58.8) | 116 (60.7) | 0.744 |

| Abnormal | 54 (38.6) | 21 (41.2) | 75 (39.3) | |

| GRACE Risk Score | ||||

| Low risk | 51 (36.4) | 20 (39.2) | 71 (37.2) | |

| Intermediate risk | 42 (30) | 19 (37.3) | 61 (31.9) | 0.384 |

| High risk | 47 (33.6) | 12 (23.5) | 59 (30.9) | |

Discussion

Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) is a term characterized by symptoms and clinical findings of acute myocardial ischemia.

The most common classic factors that promote the development of Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) can only explain 50% of the pathogenesis, prevalence, and changes in severity.[7] Recent studies have highlighted new risk factors that play a pivotal role in the physiopathology of CAD. Several studies have shown that homocysteine is one of the new risk factors for CAD. Homocysteine is a risk factor independent of other classic risk factors for cardiovascular diseases.[8-10]

Patients with acute coronary syndrome constitute a heterogenous population, showing different early and late complications and prognosis. Risk score in the early phase is important to develop treatment strategies. GRACE risk score is a model preferred in the routine of clinical practice.[11]

Each 5 Mmol/L increase in homocysteine levels increased risk by 1.8 and 1.6 times in male and female patients, respectively. This study conducted by Tokgözoğlu et al.[12] found that homocysteine levels over 15 Mmol/L increased risk for CAD by 2.1 times.

In the study using NHANES III, Ganji et al. found that men had a 1.9 Mmol/L higher homocysteine levels than women. However, no significant difference was detected in male and female patients in our study group.

Homocysteine levels of the patients with classic risk factors were significantly high in patients who smoked. In the studies conducted by Nygard and Bergmak, there was a meaningful relationship between the number of cigarettes smoked per day and elevated homocysteine levels.[13-15] Kato et al.[16] stated that women who smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day had an 18% higher homocysteine level. Nevertheless, in our study group, there was no related statistically significance between daily smoking and homocysteine levels.

It has been suggested many times that there is a direct relation between homocysteine and age.[13, 17] In the Framingham study, it was stated that patients over the age of 65 had a 23% higher homocysteine levels than patients aged below the age of 45.[18] Two options are available to explain the elevated homocysteine levels. The first option is the age-related decline in renal function, and the second option is the age-related decline in cystathionine β-synthase and other enzymes in homocysteine metabolism.[19, 20] Age-related serum folate and vitamin B12 deficiency may also cause high homocysteine levels.[21, 22] In our MI with ST-elevation group, a meaningful correlation was noticed between homocysteine and age.

In the SHEP study, a positive correlation was seen between homocysteine and systolic blood pressure. In this study, homocysteine was an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis in normotensive patients, whereas it could not be assessed as a risk factor in hypertensives.[23]

In the Non-ST MI group, a statistically moderate positive correlation was seen between homocysteine and GRACE risk score during the study (p<0.05). However, in the MI with ST-elevation group, no such correlation was found (p> 0.05). Overall, despite the low figures, a meaningful positive relation was observed between homocysteine and GRACE risk score in all cases. In the study which was published in the journal of the Turkish Society of Cardiology in 2009, no significant relationship was found between homocysteine levels in Non-ST MI patients and TIMI, as well as GRACE risk scores.

Homocysteine is independent of other classic risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, we believe that routine plasma homocysteine levels should be checked when evaluating risk factors for Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease.

Disclosures

Ethics Committee Approval: The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Authorship Contributions: Concept – F.P.T., F.B.; Design – F.P.T., F.B.; Supervision – A.C., F.P.T., F.B.; Materials – A.C., F.P.T., F.B.; Data collection &/or processing – A.C., Y.A.O., E.E.M., E.G.C., N.D.; Analysis and/or interpretation – A.C., F.P.T., F.B.; Literature search – A.C., F.B.; Writing – A.C.; Critical review – F.P.T., F.B.

References

- 1.Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990-2020. Nat Med. 1998;4:1241–3. doi: 10.1038/3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.TEKHARF. Oniki Yıllık İzleme Deneyimine Göre Türk Erişkinlerinde Kalp Sağlığı. Prof. Dr. Altan Onat, Prof. Dr. Vedat Sansoy, Prof. Dr. İnan Soydan, Prof. Dr. Lale Tokgözoğlu, Prof. Dr. Kamil Adalet. İstanbul:Argos. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Castelli WP. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality. The Framingham Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:737–41. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grayston JT, Kuo CC, Wang SP, Altman J. A new Chlamydia psittaci strain, TWAR, isolated in acute respiratory tract infections. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:161–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607173150305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malinow MR, Kang SS, Taylor LM, Wong PW, Coull B, Inahara T, et al. Prevalence of hyperhomocyst(e)inemia in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Circulation. 1989;79:1180–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.6.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harker LA, Ross R, Slichter SJ, Scott CR. Homocystine-induced arteriosclerosis. The role of endothelial cell injury and platelet response in its genesis. J Clin Invest. 1976;58:731–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI108520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solberg LA, Enger SC, Hjermann I, Helgeland A, Holme I, Leren P, et al. Risk factors for coronary and cerebral atherosclerosis. Oslo Study In Atherosclerosis V. In: Gotto AM, Smith LC, Allen B, editors. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1980. pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueland PM, Refsum H, Brattstrom L. Plasma homocysteine and cardiovascular disease. In: Francis RB Jr, editor. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, hemostasis, and endothelial function. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1992. pp. 183–236. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boushey CJ, Beresford SA, Omenn GS, Motulsky AG. A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. Probable benefits of increasing folic acid intakes. JAMA. 1995;274:1049–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530130055028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer EL, Jacobsen DW, Robinson K. Homocysteine and coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:517–27. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Araújo Gonçalves P, Ferreira J, Aguiar C, Seabra-Gomes R. TIMI, PURSUIT, and GRACE risk scores:sustained prognostic value and interaction with revascularization in NSTE-ACS. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:865–72. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tokgözoğlu SL, Alikaşifoğlu M, Unsal Atalar E, Aytemir K, Ozer N, et al. Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase genotype and the risk and extent of coronary artery disease in a population with low plasma folate. Heart. 1999;81:518–22. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.5.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nygård O, Vollset SE, Refsum H, Stensvold I, Tverdal A, Nordrehaug JE, et al. Total plasma homocysteine and cardiovascular risk profile. The Hordaland Homocysteine Study. JAMA. 1995;274:1526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530190040032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai WC, Li YH, Tsai LM, Chao TH, Lin LJ, Chen TY, et al. Correlation of homocytsteine levels with the extent of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with low cardiovascular risk profiles. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmark C, Mansoor MA, Svardal A, de Faire U. Redox status of plasma homocysteine and related aminothiols in smoking and nonsmoking young adults. Clin Chem. 1997;43:1997–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mansoor MA, Kristensen O, Hervig T, Drabløs PA, Stakkestad JA, Woie L, et al. Low concentrations of folate in serum and erythrocytes of smokers: methionine loading decreases folate concentrations in serum of smokers and nonsmokers. Clin Chem. 1997;43:2192–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganji V, Kafai MR Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Demographic, health, lifestyle, and blood vitamin determinants of serum total homocysteine concentrations in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:826–33. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.4.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacques PF, Bostom AG, Wilson PW, Rich S, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J. Determinants of plasma total homocysteine concentration in the Framingham Offspring cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:613–21. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.3.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norlund L, Grubb A, Fex G, Leksell H, Nilsson JE, Schenck H, et al. The increase of plasma homocysteine concentrations with age is partly due to the deterioration of renal function as determined by plasma cystatin C. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1998;36:175–8. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1998.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gartler SM, Hornung SK, Motulsky AG. Effect of chronologic age on induction of cystathionine synthase, uroporphyrinogen I synthase, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activities in lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:1916–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker KL, Selhub J, Wilson PW, Rosenberg IH. Dietary intake pattern relates to plasma folate and homocysteine concentrations in the Framingham Heart Study. J Nutr. 1996;126:3025–31. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.12.3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Asselt DZ, de Groot LC, van Staveren WA, Blom HJ, Wevers RA, Biemond I, et al. Role of cobalamin intake and atrophic gastritis in mild cobalamin deficiency in older Dutch subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:328–34. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutton-Tyrrell K, Bostom A, Selhub J, Zeigler-Johnson C. High homocysteine levels are independently related to isolated systolic hypertension in older adults. Circulation. 1997;96:1745–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]