Abstract

We consider the problem where the data consist of a survival time and a binary outcome measurement for each individual, as well as corresponding predictors. The goal is to select the common set of predictors which affect both the responses, and not just only one of them. In addition, we develop a survival prediction model based on data integration. This article is motivated by the Cancer Genomic Atlas (TCGA) databank, which is currently the largest genomics and transcriptomics database. The data contain cancer survival information along with cancer stages for each patient. Furthermore, it contains Reverse-phase Protein Array (RPPA) measurements for each individual, which are the predictors associated with these responses. The biological motivation is to identify the major actionable proteins associated with both survival outcomes and cancer stages. We develop a Bayesian hierarchical model to jointly model the survival time and the classification of the cancer stages. Moreover, to deal with the high dimensionality of the RPPA measurements, we use a shrinkage prior to identify significant proteins. Simulations and TCGA data analysis show that the joint integrated modeling approach improves survival prediction.

Keywords: AFT model, High dimensional shrinkage, horseshoe prior, Probit model, Protein expression, The Cancer Genome Atlas

1. Introduction

Suppose that we have a set of individuals who are assessed through various responses, measurement mechanisms or experiments. Furthermore, they have same predictors across these experiments and we seek to identify the common set of predictors which affects all the responses. In this paper, we specifically consider two responses, one of which is survival time and the other is a binary outcome, although our method can be extended to handle multiple mixed responses.

Rapid advances in biotechnology have allowed molecular profiling across multiple omics (genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics) levels. In particular, direct analysis of high dimensional proteomics data has received widespread attention because it represents a powerful approach to understand the pathophysiology and therapy of cancer, which cannot be achieved by analyses solely driven by genomics or transcriptomics (Li et al., 2013; Akbani et al., 2014).

The main aim of translational cancer research is to translate scientific discoveries into new methods of cancer treatment, which is immensely important for cancer control. Targeted anticancer therapy directly interferes with protein function, so that a systemic assessment of protein activation patterns has high potential to result in the identification of new biomarker candidates for further validation. We use data from reverse-phase protein arrays (RPPA). The RPPA platform can measure the protein level in a large number of samples in a cost effective manner. This is a technically robust platform and produces highly reproducible data (Ummanni et al., 2014). Baladandayuthapani et al. (2014) provide a brief overview of the RPPA data collection in our data analysis.

Motivated by this, we consider the largest publicly available genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data bank, The Cancer Genomic Atlas (TCGA). TCGA profiles and analyzes a large number of human tumors to discover molecular aberrations at the DNA, RNA, protein and epigenetic levels. See Weinstein et al. (2013) for a detailed description of the TCGA data bank and how it presents technologies that assess the sequence of the exome, copy number variation, DNA methylation, mRNA expression sequence, microRNA expression and transcript splice variation. Additional platforms applied to a subset of the tumors, including whole-genome sequencing and RPPA, provide additional layers of data to complement the core genomic data sets and clinical data.

Along with the protein expression measures, this experiment also offers clinical information such as the survival time and the tumor stage of the patients. Table 1 provides a schematic representation of the data structure. There we have a set of individuals who have two responses, such as survival and tumor stage, along with a set of covariates, i.e., the proteins. We seek to find the major actionable proteins which affect both these responses. Toward this goal we formulate a Bayesian hierarchical model which jointly models both response types regressed on the same set of predictors.

Table 1:

Data structure.

| Survival time of Subjects | Tumor Stage | Measurements of Protein Expressions |

|---|---|---|

| t1 | z1 | x11, x21, … ,x1p |

| t2 | z2 | x21, x22, … ,x2p |

| … | … | … |

| tn | zn | xn1, xn2, … , xnp |

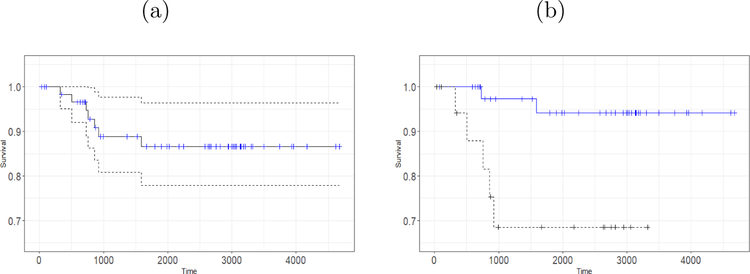

As an example, we consider the lung cancer proteomics data from TCGA. Among all the available data we consider the measurements of 195 protein expressions for 349 subjects of lung adenocarcinoma cancer patients. In addition, all measurements consist of a time to event (death) outcome along with a binary censored indicator. Approximately 71% of the observations are right censored and 23% of the subjects have advanced stage cancer. While Figure 1a provides a picture of the Kaplan-Meier plots for the subjects having lung tumor, Figure 1b depicts the Kaplan-Meier curves of the subjects corresponding to response stage and advance stage. Subjects who belong to the response stage, they respond to the therapy of the cancer and those who belong to the advanced stage their tumors are more spread and become non-responsive to the treatments. From Figure 1b it can be seen that those who have an advanced stage tumor have lower survival than those who still respond to the treatments. Our objective is to see whether our integrated modeling technique shows any improvement in terms of variable selection, model fitting, goodness of fit, and cancer survival prediction.

Figure 1:

(a) The Kaplan-Meier plot of the patients having lung cancer adenocarcinoma. The censored observations are marked as blue on the Kaplan-Meier curve. The 95% confidence interval is also shown. (b) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for response stage (blue solid line) and advanced stage (black dotted line).

Let n be the number of individuals in the data set and p be the number of covariates. Gene expression or protein expression data are of typically high dimension, sometimes p > n. To cope with this, several regularization methods (Tibshirani, 1996), and various extensions of them have been proposed in the frequentist literature. The Bayesian variable selection literature is large and dates back to George and McCulloch (1993), who devised a Gibbs sampling algorithm for variable selection. Hahn and Carvalho (2015) provide a nice review of the Bayesian techniques for high dimensional regression. Naturally, an enormous amount of research has been devoted to use a shrinkage prior on the parameters. For instance, the horseshoe prior has been shown to be extremely useful in Bayesian high dimensional analysis, as it achieves sparsity and explores the posterior parameter space successfully (Carvalho et al., 2010; Bhattacharya et al., 2016).

High dimensional regression for a survival outcome has been considered by Tibshirani (1997) in the context of Cox proportional regression. In the Bayesian setting the accelerated failure time (AFT) model setting is often preferred over the Cox model due to superior mixing properties (Sha et al., 2006). The key strategy to carry out a Bayesian analysis of the AFT model is to augment the data and then to impute the censored observations from an appropriate posterior distribution. In this paper we will show how this latent variable sampling scheme is effective in developing the joint model, and scalable to large data sets.

For the tumor samples in TCGA there are two experiments with survival outcome and disease status as the responses while the predictors are same. In this situation, because of the reasons indicated in Gao and Carroll (2017), some kind of data integration is necessary to achieve better survival prediction by integrating both of the measurements. Toward this objective, we develop a joint survival and binary model using the latent variables.

Rizopoulos et al. (2008) developed a joint model using a shared parameter approach, where the shared parameters of the two models are assumed to be random and thereby coupled using suitable Copula densities. In contrast, we estimate the parameters under a Bayesian paradigm by virtue of which the model uncertainty is also captured. In our model, the use of the common shrinkage parameters in both models helps us to select significant proteins for the joint model. In essence, one can refer to this as a shared hyperparameter model. Furthermore, the shrinkage priors on the coefficients leads to efficient variable selection in high dimensional settings.

Based on the idea of group variable regularization, Gao and Carroll (2017) proposed a data integration method in high dimensional settings, which accommodates multiple response from the same set of covariates. Parameter estimation is achieved via maximizing a pseudolikelihood. However, their goal was to select predictors which affect any one of the responses. In contrast, our objective is to find predictors which affect all the responses.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. In Section 2 we develop our hierarchical Bayesian joint model. In Section 3 we discuss our novel estimation, variable selection, and post processing techniques to draw inference from the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) samples obtained from the Bayesian analyses. Section 4 provides some simulation results showing the efficacy of our approach. We apply our methodology to the TCGA data in Section 5, followed by concluding remarks in Section 6.

2. Joint Survival and Binary Regression

2.1. Data Setup

Suppose we are interested in p proteins x1,…, xp which may be responsible for the disease outcomes of n individuals. Let (t, z) = {(t1, z1), (t2, z2),…, (tn, zn)} be the survival time and categorical outcome respectively. Our objective is to model the two responses jointly: survival time; and cancer stage, using the proteins. Throughout this article we develop the methodologies by letting z be binary {0, 1}. However, when z is a nominal categorical response then the analyses can be carried out in a similar fashion and hence more tumor stages data can be modeled. When the association between z and proteins are of interest we make use of the probit model

where βb = (βb1,…, βbp) is the regression parameter vector related to the classification model. This can be extended to logit model by introducing suitable latent variables (Polson et al., 2013)

For survival time, we consider the accelerated failure time (AFT) model

| (1) |

where βs = (βs1,…, βsp) is the vector of regression coefficients related to survival and ϵ is the error vector.

2.2. Bayesian AFT Regression

In a parametric setting, it is customary to assume that ϵ follows a parametric distribution in (1). For instance, in this article, we analyze the lognormal AFT model where ϵ ~ N(0, σ2I): other distributions such as the t distribution (Kleinbaum and Klein, 2006) can also be considered. Wei (1992) reviewed estimation strategies for parametric families of AFT models and Robins and Tsiatis (1992) showed how to incorporate time dependent covariates in the estimation. Bayesian methodologies for AFT models have been developed in many articles such as Sha et al. (2006); Walker and Mallick (1999), and Zhang et al. (2018), the first representing parametric models, the next representing semiparametric models and the last one developing nonparametric models.

Let ci be the random censoring time and suppose we observe the response pair for the ith individual, where is the observed time and δi = I(ti < ci) is the observed right censored indicator. To carry out the computations in a scalable manner, the censored observations will be imputed following data augmentation approach of Bonato et al. (2011). We denote the augmented data vector by ys = (ys1,…, ysn) where

2.3. Bayesian Binary Regression

Albert and Chib (1993) developed Bayesian probit binary models to analyze binary outcome data. To break the non-conjugacy of the probit link they followed the data augmentation approach of Tanner and Wong (1987) to define a latent variable yb which has a normal distribution with mean xTβb and variance 1. Then in the presence an of appropriate prior π(β) on the parameters, defining zi = 1 if ybi > 0 and zi = 0 if ybi < 0 leads to conjugate Gibbs sampling. This involves sampling from a truncated Normal distribution with mean and variance 1. Thus, the MCMC sampling cycles through the following steps

| (2) |

| (3) |

where π(βb|yb, z) is the appropriate posterior distribution. The choice of priors is discussed in Section 2.4 and the posterior is derived in Section 3.2.

2.4. Shrinkage Prior for Parameters

In the presence of high dimensional sparse predictors, the use of global local shrinkage priors has been shown to be effective (Carvalho et al., 2009; Bhattacharya et al., 2015). Carvalho et al. (2010) showed that all continuous shrinkage priors can be represented via scale mixtures of normal distributions; in addition, they derived several properties of the horseshoe prior. Let C+(0, 1) be the truncated Cauchy density given by f(x) = 1/{π(1 + x2)}, x > 0. In what follows, even though the horseshoe density lacks an analytical expression, motivated by global local shrinkage rules, specifying

| (4) |

in AFT model for instance, leads to shrinking the noise variables to zero while leaving the non-zero signals as they are, which is in contrast to the Bayesian lasso and Bayesian ridge hierarchies where the shrinkage effect is uniform across all coefficients. The beauty of this prior specification is that the choice of a truncated Cauchy distribution for the local hyperparameter λj helps to build different shrinking factors for different predictors; this is similar to the adaptive lasso (Zou, 2006) or the Bayesian adaptive lasso (Leng et al., 2014). Additionally, the same truncated Cauchy prior for the global hyperparameter τs results in aggressive shrinkage of the zero coefficients; and this phenomenon is similar to the spirit of the reciprocal lasso proposed recently by Song and Liang (2015), where a nearly infinite penalty is imposed on the noise.

2.5. Prior Specification Toward Common Protein Selection

In (4), τs allows borrowing strength across different cancer survivals and proteins, while λj’s provide protein specific deviations. Intuitively, λj or a function of λj defines a local shrinkage rule for βsj. Specifically, for the horseshoe prior, the behavior of can be studied to gain insight of the resulting estimator. In what follows, λj plays a crucial rule for the corresponding protein to be incorporated in the simplified fitted model. Keeping this in mind and to encourage sparsity in the integrated modeling structure, the prior elicitation for the binary probit model is

| (5) |

This describes the prior specification toward the selection of common variables present both in the survival and the binary models. We note that in order to select the common proteins we have specified same local parameter λ for both models but two different global parameters τs and τb. Even though the same hyperprior C+(0, 1) is assumed for τs in (4) and for τb in (5), one may not be able to carry out the analysis by setting τs = τb, because the scale of two responses such as survival and binary are different and hence it is important to differentiate between the two global parameters τs and τb in the joint model. Moreover, the specification of the same λj in both models is the key strategy to accomplish recovering the common proteins which are responsible for both of the survival times of the subjects and of the classification of the tumor stages of them. More details will be outlined in Section 3.3. While Table 2 provides a description of the parameters and hyperparameters presented in the joint model for variable selection purpose, Section 2.7 completes the prior elicitation incorporating the correlation among the two responses.

Table 2:

Survival model and Binary model with their parameters and hyperparameters for variable selection purposes.

| Survival Response | Binary Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Observed Response | (t*, δ) = ((, δ1), … ,(, δn))T | z = (z1, … , zn)T |

| Latent Variable | ys = (ys1, … ,ysn)T | yb = (yb1, … ,ybn)T |

| Parameters | βs = (βs1, … ,βsn)T | βb = (βb1, … ,βbp)T |

| Local hyperparameters (SAME for both experiments) | λ = (λ1, … ,λp)T | λ = (λ1, … ,λp)T |

| Global hyperparameters | τs | τb |

2.6. Specification of Distinct τs and τb

It is important that we have assumed τs ≠ τb to carry out the sampling from the posterior distributions. Here we provide an argument and necessary evidence to justify this hyperparameter specification. First, the survival response is continuous and is possibly censored. Hence to adopt a fully Bayesian analysis we impute the censored data at each iteration of the MCMC. The binary outcome is discrete data and hence to take advantage of the latent data analysis one must impute the observations for all samples. Obviously, these may create different scales for different responses. This is why we specify the shrinkage parameter τs and τb to be different. As an illustration we have observed a complete divergence in the MCMC chain when specifying one single global parameter as opposed to the two global shrinkage parameters.

2.7. Correlation between Survival and Binary Outcomes

It is important here that the tumor survival and tumor stage observations correspond to the same sample. Obviously, one expects that the two responses are correlated. In our joint model, this can be captured via a specification of a correlation term between two responses. Mathematically, with the notation of the latent variable ys and the augmented variable yb for survival response and binary response respectively, we have

| (6) |

In theory, any prior distribution having only positive support can be assumed for σ2 such as the Inverse Gamma distribution. However, to carry out the posterior sampling care must be taken to maintain the positive definiteness of the variance covariance matrix Σ. Toward this goal and to obtain good mixing in the Markov chain it is advantageous to sample from the entire real line . So, for computational ease we assume that σ2 follows a standard Lognormal distribution. Here a random variable U is said to follow the standard Lognormal distribution if and only if log(U) follows the standard Normal distribution such that in the log scale the proposal distribution for σ2 becomes the Normal distribution. In addition, we assume σ12 follows a standard Normal distribution independently of σ2.

2.8. The Hierarchical Model

Hence, after introduction of the latent variables ys = (ys1,…, ysn)T and yb = (yb1,…, ybn)T, we can specify the complete hierarchical representation of the model (6) and , and We assume half Cauchy prior on the hyperparameters λj ~ C+(0,1), τs ~ C+(0, 1), τb ~ C+(0, 1). The priors on the variance components are σ2 ~ Lognormal(0, 1) and σ12 ~ Lognormal(0, 1).

3. Computation and Inference via MCMC

3.1. Outline

In this section we derive the MCMC scheme required to obtain the posterior samples from the posterior distributions of the parameters derived from our model formulation in the previous section. The variable selection strategy and other posterior inference techniques are also discussed.

3.2. Conditional Distributions and Posterior Computation

In our joint model, some of the conditional distributions are available explicitly, and hence Gibbs sampling techniques can be employed to explore the posterior distribution. In particular, the complete conditional distributions of βs and βb are given by

where , and The censored observations are sampled from

and yb are updated from truncated Normal distributions according to (2) and (3). The routine to sample from truncated Normal distributions is now available in standard software such as the msm (Jackson, 2011) R package.

The prior elicitation of σ2 and σ12 provides a framework to carry out the posterior analysis using the Metropolis-Hastings scheme. According to this method, at mth iteration, we propose a new value from a proposal kernel such that ; then the proposed values are accepted with the appropriate Metropolis-Hastings kernel probability otherwise the existing values are retained.

Due to the nature of the priors on λ, τs, and τb, a straightforward Gibbs sampling approach may not be possible. However, several samplers have now been suggested, for instance, Makalic and Schmidt (2016) proposed an Inverse Gamma scale mixture representation of the truncated Cauchy distribution to carry out the Gibbs sampling. An alternative approach has been discussed in the online supplement of Polson et al. (2014) which is adopted here. Then

Defining and introducing a latent parameter uj, the conditional posterior distribution becomes .

Then the following scheme will be used to sample the posterior distribution of λj

Sample uj|ϕj ~ U{0, (1 + ϕj)−1}.

Sample ϕj|β,τs,τb ~ truncated Gamma .

Compute .

Updating τs can be carried out in the similar fashion. We introduce a latent variable vs and let to yield posterior samples as

Sample vs|ξs ~ U{0, (1 + ξs)−1}.

Sample ξs|vs,β,λ ~ truncated Gamma .

-

Compute .

Similarly, τb can be sampled using βb and a suitably chosen latent variable.

3.3. Common Protein Selection from MCMC Output

In high dimensional protein expression data, e.g., TCGA, a common question is which proteins are important to predict the subject’s disease status. Frequentist procedures such as lasso or other extensions of lasso are designed to provide a sparse solution of the parameter vector. A Bayesian method, however, provides the posterior distribution of the parameter from which a posterior summary is extracted to make inferences. Motivated by this, researchers seek a unified proposal for obtaining good choice of the posterior summary which in turn recovers important features in high dimensional settings. Recently, Li and Pati (2017) proposed a k-means clustering on the posterior space. When a shrinkage prior such as the horseshoe is used, even though the posterior estimate of β are not exactly zero, the MCMC sample obtained from posterior distribution of β is expected to produce two subsets – one set will be clustered around zero corresponding to noise variables and the other one will be away from zero corresponding to signals. Hence, fitting a k-means algorithm with k = 2, makes sense to determine the cluster of significant predictors i.e. the cluster with smaller size.

As mentioned previously, the objective here is to identify the common proteins which are responsible for explaining the both time to event outcome and binary outcome simultaneously. Toward this end, we propose to fit a 2-means clustering algorithm on the posterior mean of λ; the cluster which will have smaller size can be mapped to the corresponding proteins which are significant for both survival model and the binary model. Even though we have used two global parameters τs and τb and corresponding distinct regression coefficients βs and βb, consideration of clustering the estimates the of the common parameter λ successfully uncovers the true predictors present in the both models which will be evident from the simulation studies discussed in Section 4.

3.4. Prediction of the Survival Curve

When the interest is to predict a new observation Tnew given its disease status Znew, then log Tnew|Znew = ∫ys ∫βs ∫λ ∫τ E(log Tnew|ybnew)p(ys,βs,βb,λ,τ,σ2|t*,δ)dysdβsdβbdλdτdσ2, where the integration is taken with respect to the posterior predictive distribution. Since the exact evaluation of this is not viable we use the corresponding MCMC estimate

| (7) |

where and M is the posterior sample size after discarding initial burn-in samples.

In a very similar manner one obtains the estimated survival probability at time t0

3.5. Goodness of Fit

There exist several model validation criteria such as log pseudo marginal likelihood, Geisser (1980), L-measure (Ibrahim and Laud, 1994), or DIC (Spiegelhalter et al., 2002). In the literature, the application of these criteria in survival settings are also discussed, for example, see Brown et al. (2005); Ibrahim et al. (2005); Rizopoulos and Ghosh (2011). In this paper, to measure the goodness of fit, we consider the Deviance Information Criterion combines goodness of fit of a model with a penalty for model complexity and is defined, as the model deviance + 2× (effective number of parameters), evaluated at a posterior point estimate of the parameter, In particular, where D(θ) = −2 log f(.|θ), f(.|θ) is the likelihood function of the model and is an estimate of the model parameter θ. In the above expression pD is termed as the effective number of parameters and is defined as , where is a posterior point estimate of the deviance. In our joint model it is possible to partition the likelihoods over survival and binary coordinates and thus to obtain the DIC for survival and binary components respectively.

In addition, a standard comparative predictive approach, the Brier Score (Graf et al., 1999) which uses the predicted survival times, is

where denotes the Kaplan-Meier estimate (Kaplan and Meier, 1958) of the censoring distribution which is based on the observations (ti, 1−δi), and stands for the estimated survival function. As the mathematical form suggests, the Brier Score provides a numerical comparison between observed and estimated survival functions, and has been shown to be useful in measuring the goodness of fit of a survival model (Schumacher et al., 2007; Bonato et al., 2011). The Brier Score is defined for each time point t, and hence can be added for the entire time range to obtain the Integrated Brier Score, : models with smaller scores are preferred, however, IBS only works properly if not evaluated on the data used for estimation. We compute IBS using the ipred package (Peters and Hothorn, 2017).

We also compute the prediction square error by comparing the observed data and their posterior predicted values. However, for censored observations computation of this metric is not sensible, so we consider only the observed time points. Moreover, assuming censoring occurs at random this will not violate the direction of the results.

4. Frequentist Operating Characteristics in Simulated Examples

In this section, we consider high dimensional, and p > n case studies setting with n = 100, 250, 500, and p = 200 and p = 1000. The design matrix X is generated from the Normal distribution. For both the parameter vector βs and βb, we set first 10 coefficients as nonzero, i.e., signal, and rest as zero, i.e., noise. The effect size of the signals are taken as 1 by randomly assigning positive or negative signs. We first generate two latent responses ys and yb with same mean Xβ and a covariance matrix with unit diagonal elements and off-diagonal elements as either 0.5 or 0.9. This creates a compound symmetry structure in the data and the latent variables are either moderately correlated or highly correlated respectively. Then, the elements of the binary response z is zi = I(ybi > 0), i = 1,…, n. while the survival response is computed via t = exp(ys). However, in order to assess our methodology in censored situations a censoring time c is sampled from a Gamma distribution, so, the censored response is a pair . Typically, the censoring rate can be changed by considering different shape and scale parameters of the censoring distribution. We consider two censoring rates: 38% and 73% censoring. This gives us 8 simulation scenarios for each sample size and for each scenario we generate 100 data sets.

To see whether the integrated model analysis is more effective than that of a single response, we also fit a Bayesian accelerated failure time model to the survival data and a Bayesian probit binary model to the binary outcome data (result not shown). When fitting the single models the same horseshoe prior is placed on the regression parameters and the censored data are imputed as in the integrated model. In addition, we fit the Cox proportional hazard Lasso provided by the glmnet() function of the glmnet package (Simon et al., 2011). We summarize the posterior results using 5000 burn-in and 15000 MCMC samples.

For the prediction summaries such as MPSE (mean prediction square error) and IBS, one requires a test set, for which we design a test design matrix of 100 samples having a similar set up as the training set. Furthermore the summaries such as false negative rates and DIC are calculated based on the training set of the 100 simulated data sets. In addition, we report the dimension of the selected models recovered by each of the method. In Table 3 we report the mean values obtained from 100 data sets when n = 250. Additionally, Tables S1 and S2 in the supplementary material summarize the results for n = 100 and n = 500 respectively. When n = 250, for each dataset the posterior MCMC takes about 3.58 minutes per 1000 iterations for the integrated model whereas when fitting the single survival model it takes about 1.04 minutes per 1000 iterations in an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7–3770 CPU 3.40 GHz with 8 GB RAM and 64-bit Operating System machine.

Table 3:

Dimension of the selected model (LSM), True Positive Rate (TPR), False Positive Rate (FPR), False negative rates (FNR), Mean square error of β, mean prediction squared error (MPSE), Integrated Brier Scores (IBS), and DIC for integrated model and single (AFT) model. The sample size n = 250.

| Correlation | p | lasso | lasso | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 250 | ||||||||

| Censoring: 38% | Censoring: 73% | |||||||

| 0.5 | 200 | LSM | 14.350 | 12.900 | ||||

| TPR | 0.605 | 0.445 | ||||||

| FPR | 0.044 | 0.044 | ||||||

| FNR | 0.400 | 0.760 | ||||||

| MPSE | - | - | ||||||

| IBS | - | - | ||||||

| DIC | - | - | ||||||

| 1000 | LSM | 17.250 | 15.850 | |||||

| TPR | 0.600 | 0.255 | ||||||

| FPR | 0.010 | 0.013 | ||||||

| FNR | 0.680 | 0.885 | ||||||

| MPSE | - | - | ||||||

| IBS | - | - | ||||||

| DIC | - | - | ||||||

| 0.9 | 200 | LSM | 10.600 | 14.100 | ||||

| TPR | 0.620 | 0.425 | ||||||

| FPR | 0.023 | 0.058 | ||||||

| FNR | 0.320 | 0.715 | ||||||

| MPSE | - | - | ||||||

| IBS | - | - | ||||||

| DIC | - | - | ||||||

| 1000 | LSM | 18.100 | 15.200 | |||||

| TPR | 0.590 | 0.260 | ||||||

| FPR | 0.012 | 0.013 | ||||||

| FNR | 0.620 | 0.890 | ||||||

| MPSE | - | - | ||||||

| IBS | - | - | ||||||

| DIC | - | - | ||||||

Table 3 shows that the performance of variable selection and prediction improves significantly when a integrated model is fitted over a single survival model. For example, when there are about 38% censored observations and we consider moderate correlation 0.5 between the two responses, p = 1000, the false negative rate for the integrated model is 0.24 which is much lower than 0.40 that produced by the Bayesian AFT regression (single) and 0.68 produced by Lasso applied to a Cox proportional hazard model. Furthermore, the mean prediction square error and integrated Brier Score for the integrated model are also lower than the single model (these matrices were not available in the software routines which were used to fit Lasso regression). The model selection criterion DIC for the integrated model is 514 is also lower than that for the single model, suggesting that the joint model provides a better fit. We notice that when sample size n = 100 (Table S1) or n = 500 (Table S2) we observe similar behavior of the improved performance of the integrated model over the single model.

5. Protein Expression Data

5.1. Lung Tumor Data in TCGA

Lung cancer accounts for more deaths than any other cancer in both men and women, about 26 percent of all cancer deaths. In 2018, an estimated 234,030 Americans were expected to have been diagnosed with lung cancer and 154,050 deaths were reported from their disease in the United States (Siegel et al., 2018).

Lung cancers are broadly classified into two groups: small cell lung cancers and non-small cell lung cancers. Small cell lung cancers comprise about 10–15% of lung cancers, whereas non-small cell lung cancers comprise the 85% of all cases. Non-small cell lung cancer has three main types designated by the types of the cells found in the tumors, namely adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma. Among them we consider the measurements of 195 protein expressions for 349 subjects of adenocarcinoma cancer patients. Our objective is to see whether our integrated modeling technique shows any improvement in the result and toward this goal we apply our integrated Bayesian model in this data.

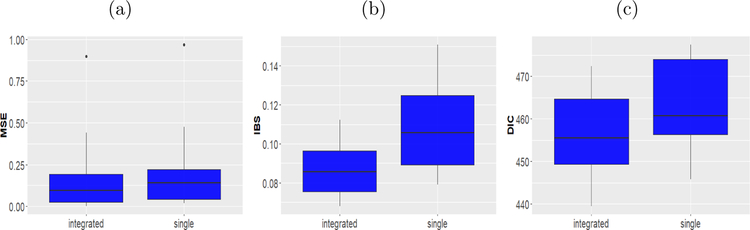

The model fitting and assessment proceeds as follows. We split the data into a training sample and a test sample. Approximately 75% of the data are kept in the training set to build the model, that is we build the model using a randomly selected 262 samples and the test set consisted of remaining 87 samples. In turn, using the posterior summaries from the training sets we obtain the MSE and IBS for the test set. In order to compute IBS, for both the single model and the joint model the average Kaplan Meier estimate was considered which was averaged over the two stages of the cancer. In addition, we also compute the DIC for the training sets. To avoid the sensitivity of a particular split we repeat this cross validation procedure 50 times. We report the mean of the cross validated numbers in Table 4. The box plots based on the repeated cross validation are provided in Figure 2. It is expected that with the help of the integrated model we see improvement in the prediction of the survival after selecting the major actionable proteins which is evident from these summaries of the experiment. For example, the MSE and IBS for the integrated model is 0.184 and 0.090 respectively which are lower than those of the single model (0.214 and 0.114 respectively). Thus, the integrated modeling improves the predictive performance of that of the single survival model. Additionally, the DIC values for the two models are 452.816 and 458.755 respectively. This suggests that the integrated modeling provides a better fit to the data.

Table 4:

Mean prediction square error, Integrated Brier Scores (IBS) and DIC based on cross validated experiment for lung adenocarcinoma tumor data in TCGA. The reported values are the mean of 100 cross validations.

| integrated | single | |

|---|---|---|

| MPSE | 0.184 | 0.214 |

| IBS | 0.090 | 0.114 |

| DIC | 452.816 | 458.755 |

Figure 2:

(a) The box plot of the mean prediction square errors (MSE) of the observed survival times and the posterior predicted survival times based on the test sets. (b) The box plot of the Integrated Brier Score (IBS) based on the test sets. (c) The box plot of the deviance information criterion (DIC) of the survival models based on the training sets. In all figures the left hand side box presents results obtained by the integrated model and the right hand side box presents results obtained by the survival AFT model.

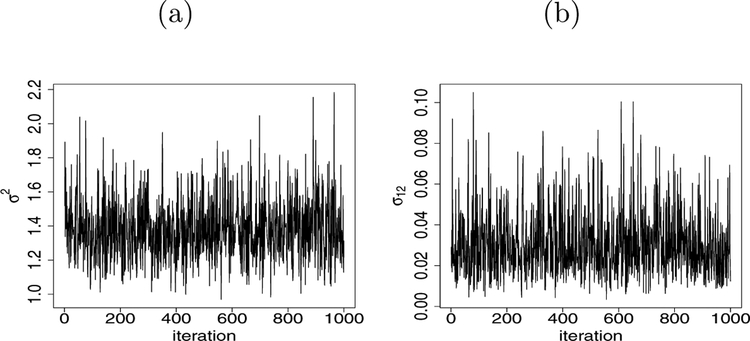

Next we proceed to discover the common protein expressions which are responsible for the cancer survival and the tumor stage of the subjects. Toward this we fit our integrated model on the full data set available in TCGA and found that the estimated correlation between the two latent variables is 0.167. Additionally, we produce the posterior trace plot for σ2 and σ12 in Figure 3. We observe the good mixing with 100,000 posterior samples after discarding 5,000 burnin and storing every 100-th sample to reduce the autocorrelation. The mixing of other parameters is consistent with the usual horseshoe prior framework.

Figure 3:

(a) The trace plot of posterior samples for σ2 in lung tumor data. (b) The trace plot of posterior samples for σ12 in lung tumor data. The plots are obtained as a result of fitting the integrated model.

In Table 5 we list the common significant proteins discovered by the joint model fitted on the data. No surprisingly, these proteins are known to be associated with the growth and progression of the lung cancer. For instance, the association of the expression level of CD49b and cancer stem cells within the tumors has been well documented in the literature (Wang et al., 2013), and in turn it is related to the resistance to therapy of the lung tumor. In addition, we identified Ku80, which has been shown to be highly expressed in lung adenocarcinoma and promotes drug resistance (Ma et al., 2012). Similarly, p90RSK has been demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of cell proliferation in various malignancies through indirect, e.g., modulation of transcription factors, or direct effects on the cell-cycle machinery and hence irregular expression of it has been demonstrated in lung cancer (Poomakkoth et al., 2016).

Table 5:

Significant proteins in the lung tumor data found by the integrated model.

| Protein | Posterior Mean | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CD49b | −0.13 | This is an extracellular receptor for laminins (high-molecular weight proteins of the extracellular matrix). |

| Ku80 | −0.18 | This helps to make up the Ku heterodimer, which binds to DNA double-strand break ends. |

| p90RSK | 0.23 | This is a family of protein kinases involved in signal transduction. |

5.2. Kidney Tumor Data in TCGA, p > n

We apply the methodologies described above in TCGA kidney tumor data. There are three types of kidney cancers viz. kidney chromophobe (KICH), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), and kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP). According to Linehan and Ricketts (2013), all types of kidney cancer are different, making it even more important to characterize each one. In 2017, it is estimated that there will be 65,340 new cases of kidney cancer and 14,970 deaths as a result of this disease (Siegel et al., 2018). Chromophobe kidney cancer accounts for five percent of these cancer cases. On the other hand, Renal Cell Carcinoma is the most common type of kidney cancer which are broadly classified into renal clear cell carcinoma and renal papillary cell carcinoma.

The protein data for chromophobe kidney tumor has 62 samples with 195 proteins that is this group has more number of proteins than the number of observations (p > n). In addition, approximately 88.7% samples are censored and Figure 4a presents the Kaplan-Meier plot. Among all the individuals about 30% are observed to posses an advanced stage of cancer and in Figure 4b we depict the Kaplan-Meier curves of the advanced group and response group.

Figure 4:

(a) The Kaplan-Meier plot of the patients having chromophobe kidney cancer. The censored observations are marked as blue on the Kaplan-Meier curve. The 95% confidence interval is also shown. (b) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for response stage (blue solid line) and advanced stage (black dotted line).

We carry out our cross validation analysis after applying our methodology in the training sets and assessing the performance on the test sets. To avoid sensitivity of a particular split of training data and test data we repeat the cross validation 50 times. Table 6 summarizes the result of the full cross validation experiment. The results are consistent with the previous results indicating that the integrated model provides a better fit to the data over the single model.

Table 6:

Mean prediction square error, Integrated Brier Scores (IBS) and DIC based on cross validated experiment for kidney chromophobe tumor data in TCGA. The reported values are the mean of 100 cross validations.

| integrated | single | |

|---|---|---|

| MPSE | 3.42 | 4.61 |

| IBS | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| DIC | 25.28 | 54.84 |

Next we fit the integrated model on the full kidney chromophobe tumor protein data extracted using RPPA technology. The estimated correlation between two responses results in 0.17. The identified common proteins are listed in Table 7 based on the Markov chain fitted on the data. We notice that the significant proteins found by our analysis has been already shown to have association with the cancer survival in the literature. For instance, Muranen et al. (2016) discussed the effects of X53BP1 and MAPK on the tumor growth. In a recent analysis Gagat et al. (2018) showed that how A.Raf_pS299 is correlated with cancer progression. Similar studies can be found for other proteins in the list.

Table 7:

Significant proteins in kidney tumor data found by the integrated model.

| Protein | Description |

|---|---|

| X53BP1 | This is a participant in the DNA damage response pathway |

| A-Raf_pS299 | This is encoded by ARAF Gene |

| ATM | This is a serine/threonine protein kinase that is recruited and activated by DNA double-strand breaks |

| CD49b | This is an extracellular receptor for laminins (high-molecular weight proteins of the extracellular matrix). |

| Cyclin_E1 | This is encoded by CCNE1 gene and belongs to the highly conserved cyclin family |

| ERCC1 | This forms the ERCC1-XPF enzyme complex that participates in DNA repair and DNA recombination |

| GSK3.alpha.beta_pS21_S9 | This mediates the addition of phosphate molecules onto serine and threonine amino acid residues |

| MAPK_pT202_Y204 | This belongs to MAP kinase family which act as an integration point for multiple biochemical signals |

| MEK1 | The protein encoded by this gene is a member of the dual-specificity protein kinase family that acts as a mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| PI3K.p110.alpha | This is a class I PI 3-kinase catalytic subunit and encoded by the PIK3CA gene |

| Tuberin_pT1462 | This is encoded by the TSC2 gene mutations in which lead to tuberous sclerosis |

| YB.1 | This is a member of the family of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins with an evolutionarily ancient and conserved cold shock domain |

| eIF4E | This recognizes and binds the 7-methylguanosine containing mRNA cap during an early step in the initiation of protein synthesis and facilitates ribosome binding by inducing the unwinding of the mRNAs secondary structures |

6. Conclusion

We developed a Bayesian hierarchical methodology to jointly model both survival and binary responses. Using simulation and TCGA data, we have shown the efficacy of our methodology. We showed that using same set of shrinkage parameters on the coefficients helps borrow strength and provides an easy selection method for the common proteins. Furthermore, the use of shrinkage priors attains sparsity and our scalable computation strategy makes this handle high dimensional situations.

In our methodology, we carry out the posterior sampling of the variance parameter σ2 upon specifying the Lognormal distribution in the prior space. An alternative approach could be the specification of Inverse Gamma distribution on σ2. However, we have observed a slow acceptance rate in the MCMC although similar performance in terms of the variable selection. For example, specifying the Inverse Gamma distribution provides about only 2% acceptance rate. In the contrary, the Lognormal prior assumption provides 45% of the samples being accepted.

The idea behind our proposed method is very general which in turn allows many immediate extensions for future research. As pointed out, classification with more than two categories can be carried out using a Bayesian multinomial model. In fact, we hope for similar improvement for any discrete outcome such as count data or zero inflated data. Following Lee and Mallick (2004), the Gamma process prior can be placed on the baseline cumulative hazard function to incorporate Cox proportional hazard model instead of AFT model. Here we have considered two experiments, namely, survival and classification. Our future research plan includes exploration of multiple experiments with data integration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors were supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (U01-CA057030, R01-CA194391). The authors thank the editor and the reviewers for the helpful suggestions which substantially improved this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The code for this paper is available at https://github.com/arnabkrmaity/intsurvbin. Additional simulation results are available in the supplementary material.

Contributor Information

Arnab Kumar Maity, Early Clinical Development Oncology Statistics, 10777 Science Center Drive, Pfizer Inc., San Diego, CA 92121.

Raymond J. Carroll, Department of Statistics, Texas A&M University, 3143 TAMU, College Station, TX, 77843-3143, and School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, Broadway NSW 2007, Australia

Bani K. Mallick, Department of Statistics, Texas A&M University, 3143 TAMU, College Station, TX, 77843-3143

References

- Akbani R, Ng PKS, Werner HM, Shahmoradgoli M, Zhang F, Ju Z, Liu W, Yang J-Y, Yoshihara K, Li J, et al. (2014). A pan-cancer proteomic perspective on The Cancer Genome Atlas. Nature Communications, 5, 3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert JH and Chib S (1993). Bayesian analysis of binary and polychotomous response data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88, 669–679. [Google Scholar]

- Baladandayuthapani V, Talluri R, Ji Y, Coombes KR, Lu Y, Hennessy BT, Davies MA, and Mallick BK (2014). Bayesian sparse graphical models for classification with application to protein expression data. Annals of Applied Statistics, 8, 1443–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A, Chakraborty A, and Mallick BK (2016). Fast sampling with Gaussian scale mixture priors in high-dimensional regression. Biometrika, 103, 985–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A, Pati D, Pillai NS, and Dunson DB (2015). Dirichlet–Laplace priors for optimal shrinkage. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110, 1479–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonato V, Baladandayuthapani V, Broom BM, Sulman EP, Aldape KD, and Do K-A (2011). Bayesian ensemble methods for survival prediction in gene expression data. Bioinformatics, 27, 359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ER, Ibrahim JG, and DeGruttola V (2005). A flexible B-spline model for multiple longitudinal biomarkers and survival. Biometrics, 61, 64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CM, Polson NG, and Scott JG (2009). Handling sparsity via the horseshoe. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, pages 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CM, Polson NG, and Scott JG (2010). The horseshoe estimator for sparse signals. Biometrika, 97, 465–480. [Google Scholar]

- Gagat M, Krajewski A, Grzanka D, and Grzanka A (2018). Potential role of cyclin F mRNA expression in the survival of skin melanoma patients: Comprehensive analysis of the pathways altered due to cyclin F upregulation. Oncology Reports, 40, 123–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X and Carroll RJ (2017). Data integration with high dimensionality. Biometrika, 104, 251–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisser S (1980). Discussion on sampling and bayes’ inference in scientific modeling and robustness (by GEP Box). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society A, 143, 416–417. [Google Scholar]

- George EI and McCulloch RE (1993). Variable selection via Gibbs sampling. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88, 881–889. [Google Scholar]

- Graf E, Schmoor C, Sauerbrei W, and Schumacher M (1999). Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Statistics in Medicine, 18, 2529–2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn PR and Carvalho CM (2015). Decoupling shrinkage and selection in Bayesian linear models: a posterior summary perspective. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110, 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim JG, Chen M-H, and Sinha D (2005). Bayesian Survival Analysis. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim JG and Laud PW (1994). A predictive approach to the analysis of designed experiments. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 89, 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CH (2011). Multi-state models for panel data: The msm package for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 38, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL and Meier P (1958). Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum DG and Klein M (2006). Survival Analysis: a Self-Learning Text. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KE and Mallick BK (2004). Bayesian methods for variable selection in survival models with application to DNA microarray data. Sankhyā: The Indian Journal of Statistics, 66, 756–778. [Google Scholar]

- Leng C, Tran M-N, and Nott D (2014). Bayesian adaptive lasso. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 66, 221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Li H and Pati D (2017). Variable selection using shrinkage priors. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 107, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lu Y, Akbani R, Ju Z, Roebuck PL, Liu W, Yang J-Y, Broom BM, Verhaak RG, Kane DW, et al. (2013). TCPA: a resource for cancer functional proteomics data. Nature Methods, 10, 1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan WM and Ricketts CJ (2013). The metabolic basis of kidney cancer In Seminars in Cancer Biology, volume 23, pages 46–55. Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Li P, Xu M, Yin J, Su Z, Li W, and Zhang J (2012). Ku80 is highly expressed in lung adenocarcinoma and promotes cisplatin resistance. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 31, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makalic E and Schmidt DF (2016). A simple sampler for the horseshoe estimator. IEEE Signal Processing Letters, 23, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Muranen T, Selfors LM, Hwang J, Gallegos LL, Coloff JL, Thoreen CC, Kang SA, Sabatini DM, Mills GB, and Brugge JS (2016). ERK and p38 MAPK Activities Determine Sensitivity to PI3K/mTOR Inhibition via Regulation of MYC and YAP. Cancer Research, pages canres–0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A and Hothorn T (2017). ipred: Improved Predictors. R package version 0.9–6.

- Polson NG, Scott JG, and Windle J (2014). The Bayesian bridge. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 76, 713–733. [Google Scholar]

- Poomakkoth N, Issa A, Abdulrahman N, Abdelaziz SG, and Mraiche F (2016). p90 ribosomal S6 kinase: a potential therapeutic target in lung cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine, 14, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos D and Ghosh P (2011). A Bayesian semiparametric multivariate joint model for multiple longitudinal outcomes and a time-to-event. Statistics in Medicine, 30, 1366–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos D, Verbeke G, Lesaffre E, and Vanrenterghem Y (2008). A two-part joint model for the analysis of survival and longitudinal binary data with excess zeros. Biometrics, 64, 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins J and Tsiatis AA (1992). Semiparametric estimation of an accelerated failure time model with time-dependent covariates. Biometrika, 79, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Binder H, and Gerds T (2007). Assessment of survival prediction models based on microarray data. Bioinformatics, 23, 1768–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha N, Tadesse MG, and Vannucci M (2006). Bayesian variable selection for the analysis of microarray data with censored outcomes. Bioinformatics, 22, 2262–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, and Jemal A (2018). Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon N, Friedman J, Hastie T, and Tibshirani R (2011). Regularization Paths for Cox’s Proportional Hazards Model via Coordinate Descent. Journal of Statistical Software, 39, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q and Liang F (2015). High-dimensional variable selection with reciprocal L1-regularization. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, and Van Der Linde A (2002). Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 64, 583–639. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner MA and Wong WH (1987). The calculation of posterior distributions by data augmentation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82, 528–540. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R (1997). The lasso method for variable selection in the Cox model. Statistics in Medicine, 16, 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ummanni R, Mannsperger HA, Sonntag J, Oswald M, Sharma AK, König R, and Korf U (2014). Evaluation of reverse phase protein array (RPPA)-based pathwayactivation profiling in 84 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines as platform for cancer proteomics and biomarker discovery. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics, 1844, 950–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S and Mallick BK (1999). A Bayesian semiparametric accelerated failure time model. Biometrics, 55, 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Gao Q, Suo Z, Munthe E, Solberg S, Ma L, Wang M, Westerdaal NAC, Kvalheim G, and Gaudernack G (2013). Identification and characterization of cells with cancer stem cell properties in human primary lung cancer cell lines. PLoS One, 8, e57020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Wei L-J (1992). The accelerated failure time model: a useful alternative to the Cox regression model in survival analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 11, 1871–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KRM, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C, Stuart JM, Network CGAR, et al. (2013). The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nature Genetics, 45, 1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Sinha S, Maiti T, and Shipp E (2018). Bayesian variable selection in the AFT model with an application to the SEER breast cancer data. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 27, 971–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H (2006). The adaptive lasso and its oracle properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 101, 1418–1429. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.