Summary

Since mid-February, 2020, coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has been spreading in Cambodia and, as of April 9, 2020, the Ministry of Health has identified 119 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive cases. However, the PCR test is available in only two specialized institutes in the capital city Phnom Penh; therefore, exact and adequate identification of the cases remains still limited. Many vulnerable newborn infants have been admitted to the neonatal care unit (NCU) at the National Maternal and Child Health Center in Phnom Penh. Although the staff have implemented strict infection prevention and control measures, formidable gaps in neonatal care between Cambodia and Japan exist. Due to the shortages in professional workforce, one family member of sick newborn(s) should stay for 24 hours in the NCU to care for the baby. This situation, however, may lead to several errors, including hospital-acquired infection. It is crucial not only to make all efforts to prevent infections but also to strengthen the professional healthcare workforce instead of relying on task sharing with family members.

Keywords: COVID-19, Cambodia, neonatal care, family, workforce, task sharing

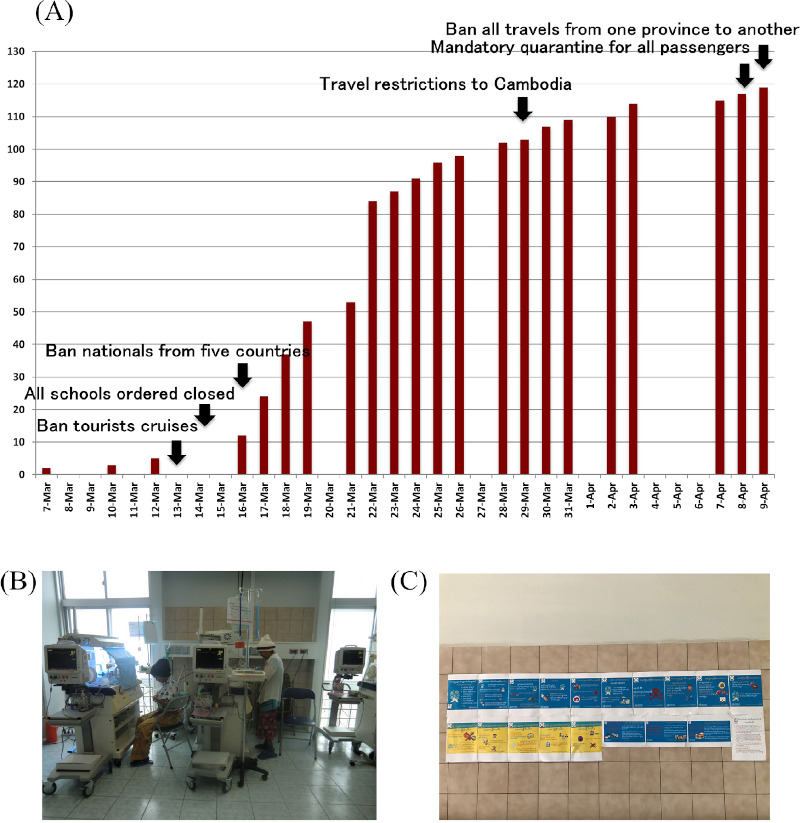

In Cambodia, the index case of COVID-19 was reported on January 27, 2020. The patient was a Chinese national traveling from China to Sihanoukville, the largest port city in Cambodia. Since mid-February, infections by the causative virus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2) have been spreading daily (Figure 1). As of April 9, 2020, the Ministry of Health (MOH) has reported a total of 119 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive cases (1). According to MOH regulations, all confirmed cases should be admitted to two designated facilities in Phnom Penh, 24 provincial hospitals, or four specialized children's hospitals (2). In Cambodia, however, the PCR test is available in only two specialized institutes in the capital city Phnom Penh; therefore, exact and adequate identification of positive cases remains highly limited. This situation makes isolation and treatment of infected individuals difficult, similar to the situation in many low- or middle-income countries.

Figure 1.

Amid the pandemic of COVID-19 in Cambodia. (A) Accumulated cases of COVID-19 and main measures in Cambodia from 7 March to 9 April in 2020 (Source: Ministry of Health, Cambodia. Press release. http://moh.gov.kh/?lang=en accessed from January 27 to April 9, 2020); (B) Care at Neonatal Care Unit; (C) General precautions and possible symptoms of the disease were displayed in the lobby of the National Maternal and Child Health Center on 13 February 2020.

The National Maternal and Child Health Center (NMCHC) is a tertiary referral hospital for obstetrics, gynecology, and neonatology in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) have conducted technical cooperation projects with the NMCHC since 1995. The total number of beds for parturient women and newborn infants is 154. The annual number of deliveries is approximately 7,500, one-quarter of which are by cesarean section, and approximately 10% of all newborns require admission to the neonatal care unit (NCU) for medical treatment (3). The main criteria for admission to the NCU include: very low birth weight (< 1,500 g); severe asphyxia; and concerning signs such as respiratory distress/disorders, fever, jaundice and convulsion, among others (4). Needless to say, every patient in the NCU is vulnerable to and at the highest risk for all types of infections.

Sufficient infection prevention and control measures are routinely implemented in the NCU in accordance with regulations from the Cambodian MOH. Regulations were strengthened in 2012 when the NCU experienced an outbreak of Klebsiella among newborn infants (5). Since then, infection prevention and control have been strictly performed in the NCU, including monthly cleaning of the facility environment using alcohol-based agents, maintaining a distance of ≥ 1 m between infant incubators, cleaning of equipment (e.g., incubators, monitors), and strict hand washing and hygiene practices among family members and staff. These systematic measures have prevented the newborn patients in the NCU from hospital-acquired infections.

Nevertheless, formidable gaps in neonatal care between Cambodia and high-income countries, such as Japan, exist. Attendance of family members is essential to all inpatients in every hospital setting. In many NCUs in Cambodia, one family caregiver, it is often the father or grandmother of the newborn patient, should remain in the NCU for 24 hours. The expected roles of the family at incubator-side include provision of essential care, such as tube feeding every three hour, diaper change(s) and measurement of body temperature. Sometimes, even respiratory support using a bag and mask is performed by the family in the NCU. Due to the shortage of professional workforce, both in quantitative and qualitative aspects, neonatal care in the NCU, in reality, cannot be provided without such task sharing among healthcare professionals and family caregivers (6). It has been reported that participation of family members in the care of sick newborn infants has a favorable impact (7); however, it may also lead to several errors including hospital-acquired infection(s).

In the NMCHC, preventive measures to avoid the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been gradually implemented. General precautions and possible symptoms of COVID-19 were prominently displayed in the lobby of the hospital on February 13, 2020. The staff increased the times of cleaning with alcohol for inside the building: every three day. Since March 26, 2020, screening of body temperature and hand hygiene using alcohol-based agents for all visitors has been mandated at the entrance of the hospital. Now the nurses of outpatient department interview all the patient women about their health condition with questionnaire sheets. However, the virus (i.e., SARS-CoV-2) can be brought into the hospital by asymptomatic infected individuals. Because the movement of people, in large part, transmits SARS-CoV-2, family members going to and from the NCU represent the highest risk factors for its infection. An effective measure to avoid virus transmission is isolation; therefore, many hospitals have restricted family visits to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in Japan (8). However, compared with Japanese NICUs, it is quite difficult to prohibit family caregivers from entering the NCUs in Cambodia because they have already been integrated into the hospital care system.

Therefore, we strongly recommend the implementation of a second independent screening test for COVID-19, which consists of measurement of body temperature and questions regarding other disease symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath), and history of close contact to confirmed cases, for all staff and family members before entering the NCU. However, if a COVID-19-positive individual is found among staff or families, temporary closure of the NCU cannot be avoided. Because delivery rooms, operation theaters, and intensive care units for parturient women are on the same floor of the building, disinfection of facilities, as well as isolation of staff, would be considered. This has a significant negative impact on maternal and neonatal health in Cambodia. Now is the time to reconsider how the professional healthcare workforce can be strengthened in Cambodia - instead of relying on task sharing with family members - to protect newborn infants and parturient women, who are among the most vulnerable patients in hospitals.

References

- 1. Ministry of Health, Cambodia. Press release. http://moh.gov.kh/?lang=en (Accessed from January 27 to April 9, 2020) .

- 2. Minister of Health Cambodia. Announcement from the Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health, Phnom Penh, 16 March 2020. http://moh.gov.kh/?lang=en (Accessed April 15, 2020).

- 3. Honda M, Som R, Seang S, Tung R, Iwamoto A. One Year Outcome of High-Risk Newborn Infants Discharged from the Neonatal Care Unit of the National Maternal and Child Health Center in Cambodia. Heliyon. 2019; 5:e01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Maternal and Child Health Center. The NCU clinical manual. 2nd version In: Chapter 2: Admission and Discharge Criteria NMCHC, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2019; pp.6. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ministry of Health, Cambodia. National Clinical Practice Guideline, Neonatal Sepsis, Definition Causes Management Prevention. In: 5. Prevention of Nosocomial Infections. Paediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines Working Group, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2013; pp.30-31. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sakurai-Doi Y, Mochizuki N, Phuong K, Sung C, Visoth P, Sriv B, Amara SR, Murakami H, Komagata T, Fujita N. Who provides nursing services in Cambodian hospitals? Int J Nurs Pract. 2014; 20 Suppl 1:39-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooper LG, Gooding JS, Gallagher J, Sternesky L, Ledsky R, Berns SD. Impact of a family-centered care initiative on NICU care, staff and families. J Perinatol. 2007; 27 Suppl 2:S32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Center for Global Health and Medicine. Notice on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). www.hosp.ncgm.go.jp/en/index.html (accessed April 15, 2020).