Summary

Japan is aging rapidly, and its society is changing. Population aging and social change are mutually linked and appear to form a vicious cycle. Post-war Japan started to invest intensively in infectious disease control by expanding health services and achieving universal medical insurance coverage in 1961. The high economic growth in the 1960s contributed to generate a thick middle class layer, but the lingering economic slump after the economic bubble crisis after 1991 and globalization weakened this segment of society. Health disparity has been acknowledged and social determinates of health have been focused. In this article, the author reviewed the response course to health challenges posed by population aging in Japan, and aims to offer lessons to learn for Asian nations that are also rapidly aging. The core viewpoints include: i) review health policy transformations until the super-aged society, ii) discuss how domestic issues in aging can be a global issue, iii) analyze its relationship with Japanese global health engagement, iv) debate the context of social determinates of health, and v) synthesize these issues and translate to future directions.

Keywords: Population aging, Japan, policy transformation, SDGs, UHC, social determinates of health

Introduction

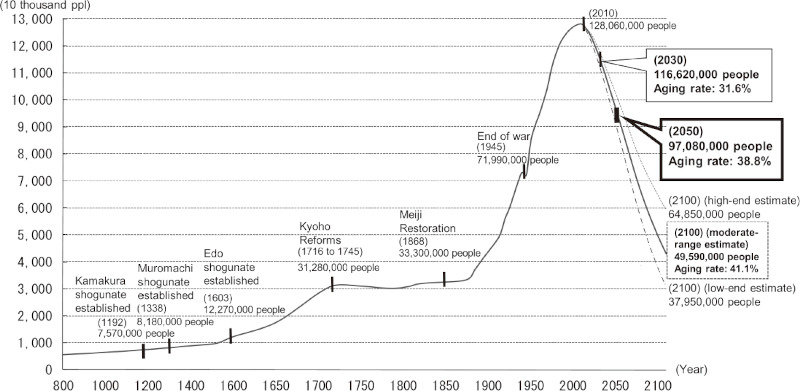

Japan is aging rapidly, those over 65 already constituted 27.7% of the total population in 2017. This figure is the highest in the world and is projected to grow continuously up to 38.4% in 2065 (1). However, population aging is a result of remarkable success in health improvement and economic development in a country or region, and a similar trend is becoming visible globally, particularly in Asia. Hence, Japan is only a front runner of a future aging world, and her experience will be beneficial for countries that are to follow. However, the demographic impact of aging is more complicated than just a growing number of senior citizens. Another side of the coin is that decline in birthrate to below the death rate results in population decrease, and especially reduction of the young workforce. The population dynamics in Japan are very dramatic, as shown in Figure 1. The Japanese population climbed to a peak within the twentieth century, and is projected to return to the level of the previous century within the next 100 years.

Figure 1.

Long-term changes in total population and estimated future population. Data source: Population to 2010: materials prepared by National Spatial Planning and Regional Policy Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure Transport and Tourism (MLIT) based on the national census results by Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) and the analysis of long-term chronological population distribution data in the Japanese islands (1974) by National Land Agency. The population thereafter: materials prepared by National Spatial Planning and Regional Policy Bureau, MLIT based on Population Projection for Japan by National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (estimated in January 2012).

This demographic change poses challenges to all aspects of life for individuals and the society as a whole. How can we extend healthy lifespan, and not merely physical longevity? How is the extended lifespan supported financially? With an increasing in-need population and declining contributors, how can we sustain the social infrastructure including social security (medical insurance and pension) and other essential services such as transportation and response capacity to natural disasters? How can we perpetuate innovations and vitality in a predominantly aged society? All these are perceived as "clear and present dangers" and shared by Japanese leaders and the population as a whole.

Japanese were proud to achieve universal medical insurance coverage and pension in 1961 (2) and believe that this achievement has contributed to generate a thick healthy middle class layer, who has brought prosperity and stability in the 60', 70' and 80'. However, a success story itself could turn out to be a hurdle to introduce necessary changes, as Jared Diamond wrote in his book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive. The courage to make painful decisions about values, "Which of the values that formerly served society well can continue to be maintained under newly changed circumstances? Which of these treasured values must instead be jettisoned and replaced with different approaches?" is critical for sustaining a society (3). These words are particularly relevant to Japan, which is already a super-aged society with low birthrate and population decline.

With the above background, in this article, the author wishes to: i) review health policy transformations until the super-aged society, ii) discuss how domestic issues in aging can be a global issue, iii) analyze its relationship with Japanese global health engagement, iv) debate the context of social health determinates, and v) synthesize these issues and translate to future directions.

Transformation of health policy until the super-aged society

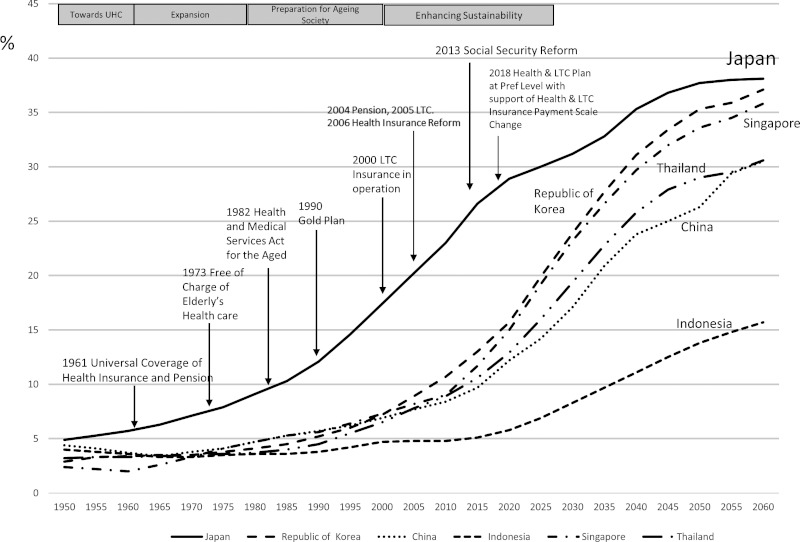

Demographic change is not readily visible in daily life and is only appreciated when it becomes too apparent suddenly. However, while experts in demography can illustrate future population size and composition relatively easily, such "inconvenient truth" is difficult to communicate to the public as well as policymakers. Early warning was voiced. For example, the late Dr. Taro Takemi, Past President of Japan Medical Association published an article on Monthly Chuo- Koron, entitled "How can we cope with the growing number of senior citizens ?" in 1955. He foresaw that population aging required changes in health care delivery and demanded a critical review of future design in social security. All his concerns have proven to be real nearly half a century later when the "inconvenient truth" becomes too visible. Figure 2 illustrates the historical development or transformation of health policy in Japan until Japan becomes a super-aged society. Aging in other countries is also plotted to show how they may plan to introduce significant policy changes when their populations become aged progressively in the future as in Japan.

Figure 2.

Aging rates of Asian countries and evolution of Japan's elderly care system. Data source: http://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2018/html/zenbun/s1_1_2.html

In this regard, the post-World War II health policies in Japan can be categorized into four phases: i) towards UHC (until 1961); ii) expansion of social security (until 1980); iii) preparation for aging society (until 2000), and iv) enhancing sustainability (until 2025).

Towards UHC (until 1961)

The central policy issues in the '50s were expansion of medical insurance and pension coverage for every citizen in Japan. Coverage started from large companies, public sectors and local communities, but small industry workers and their families were left behind. Universal coverage was finally achieved in 1961 when GDP per capita was US$563 (current equivalent) (4). At that time, the average life expectancy was 70.2 years for women and 66.0 for men, and the average age of the Japanese population was 28 years. The respective figures for 2017 were US$38,428, 87 years, 81 years for men, and 47 years.

Expansion of social security (until 1980)

The '60s were remembered for the amazing rate of economic growth, and Japan became the number 2 global economic power in 1968, replacing West Germany. Industrialization and urbanization progressed at a rapid pace. Old family-based welfare, while offering public support for impoverished people, was being challenged. The on Welfare for the Elderly Act was enacted in 1963, which expanded social support for senior citizens in need. According to the copayment system of medical insurance, service receivers should pay 30% of the cost each time they receive service (remaining 70% is directly claimed by the service providers to insurance bodies). Increasing political pressure that the 30% co-payment was discouraging senior citizens from accessing services drove the government to waive the copayment for seniors aged over 70 years in 1973. This scheme was judged feasible at that time, when the economy was strong and the proportion of senior citizens was less than 10%. The act was welcomed initially, but later proved too costly. Eventually, politicians paid a high political price when re-introducing the copayment, losing elections due to such an unpopular move. The evolution and remarkable outcomes as well as increasing challenges of the Japanese medical insurance system are well documented by Ikegami and Campbell (5).

Preparation for aging society (until 2000)

As the proportion of senior citizen increased to almost 10%, bureaucrats started to raise concerns over the trend of increasing medical expenditures. Mr. Hitoshi Yoshimura, Director-General of Insurance Bureau of Ministry of Health (1982 to 1984) and later Vice-Minister of Health (1984 to 1986) was a strong advocate of the urgent need for medical cost containment due to expensive health technologies and aging, among many other factors. Mr.Yoshimura was not shy to present his pessimistic view on the sustainability of social security, particularly medical insurance. He advocated various measures to "rationalize" medical cost. A significant outcome was the enactment of the Health and Medical Services Act for the Aged in 1982. The Act has two components: health promotion after age 40 and financial balancing mechanism to support medical insurance bodies, particularly community-based insurance bodies to pay medical bills of senior citizens.

Along with continued population aging and reduction of family size, Japan needed to consider socializing nursing care for the aged by expanding capacity of relevant institutions. Also, a consensus was reached that hospital admission due to "social" needs and not medical reasons should be a target of rationalization. This so-called "social hospitalization" phenomenon and the long waiting list to enter nursing homes became a political agenda in the national parliament as well as prefectural assemblies. This resulted in systematic investment from the public sector. The Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Home Affairs launched the "Gold Plan" in 1989 (over 65 population: 11.6%), investing 6 trillion yen to build more long-term care institutions. The plan was modified in 1994 (over 65 population: 14.1) to expand home care programs (6). These developments provided the infrastructure to introduce the long-term care insurance (LTCI) (7), which came into operation in 2000 (over 65 population: 17.4%). The LTCI covers both home and institutional care according to the assessed level of disability.

Enhancing sustainability (until 2025)

By implementation of the LTCI, the social security architecture for the aged was completed, with medical care insurance for sickness, pension for livelihood support and LTCI for long-term disability. However, upon entering the 21st century, the continuation of rapid aging and sharp birthrate decline questioned the sustainability of medical care insurance and pension. Attempts were made to increase the premium and copayment of service receivers and to enhance the efficiency of service providers as well as to expand public support for medical insurance bodies. Significant reforms were legislated in 2006 and 2015. However, it has been noted that the reform of medical insurance should be discussed in the broader context of social security. For example, the increase in demand for LTCI is greater than that for medical insurance. From 2000 to 2018, the number of users of the LTCI increased three-fold from 1.49 to 4.74 million. In response to such an increase in demand, the service cost rose from 3.6 to 10 trillion yen from 2000 to 2016, and the per capita insurance premium of senior citizens themselves also increased from 2911 to 5514 yen (8).

On the other hand, the medical cost grew but at a much moderate pace from 30.1 trillion yen in 2000 to 42.2 trillion in 2017. This was a result of tighter control of the health insurance reimbursement scheme, but this capping strategy posed challenges for both health care professionals and health care industries. A book entitled Collapse of Medical System (9) that addressed this issue became a bestseller in 2006.

In addition, due to the continued Japan economic slump after the economic bubble collapse in 1991, many young people failed to find full-fledged employment and accepted irregular jobs with less wages and lower insurance and pension contributions. Thus, social insurance premiums from workers were not raised. Altogether, balance sheets of both medical and long-term care insurance have deteriorated from reduced contributions and increased demand. The financial gaps are filled by transferring medical costs from young people to seniors within insurance bodies and infusion from tax revenues. Consequently, out of the 97.7 trillion yen government budget in FY 2018 (10), 33.8 trillion yen was spent on social security. Hence, health is the biggest budget item, six times larger than that for education, and science and technology, which is generally regarded as investment for future human capital.

All these generated needs to look at all aspects of social security by avoiding silo approaches to medical insurance and LTCI, as well as disproportionate consumption of the general budget. The government solution was to increase the consumption tax from 5% to 8% and eventually to 10% by 2019. A bipartisan agreement was reached in 2012 to use a considerable portion of the increased revenue to enhance the sustainability of social security, ahead of 2025 when the post-war baby boomers (1947-49) would reach the age of over 75 and demand greater medical and long-term care services. Hence, the National Council of Social Security Reform was called by the Cabinet Office, and a report (11) including a road map of "total reform" was submitted to the Office on 6 August 2013.

The report was perceived as unique in addressing challenges in a cross-cutting manner and recommending well coordinated policy change, taking into account changes of social, family and individual values. The report presented the grand vision and proposed reform on social measures to address the declining number of children, medical and long-term care insurance, and pension.

Convergence of global and domestic health agendas

If one turns attention to global health, it is surprising to see a convergence of the Japanese domestic agenda with the global health agenda. The life expectancy of the world has reached 71 years and many "developing countries" have graduated from being recipient countries to mid-income countries with limited access to development aid from more affluent countries. This was made possible by massive investments in control of diseases and infections (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical disease) followed by maternal and child health. The former included access to medicine and preventive measures such as anti-retroviral medicines for HIV/AIDS and long lasting insecticide-treated bed-nets for malaria. These brought a drastic decrease in deaths and an increase in a healthy workforce that drove socio-economic development in once communicable disease-affected low-income countries. In the case of tropical diseases, a typical example is onchocerciasis or river blindness. This parasitic disease was a common cause of blindness among populations along the river side in tropical regions, particularly in West Africa. River side fertile farming land was abandoned due to the disease. However, mass preventive use of ivermectin (Mectizan) almost eliminated river blindness and led to economic recovery. The vicious circle of ill health and poverty was broken. The same was observed in Japan during the early post-war period. In 1954, the leading cause of death was tuberculosis, which consumed 28% of the medical care budget (12). The most affected population was young students and workers. Japan aggressively controlled tuberculosis by mass screening and case management at public health centers together with public financial support for care under official diagnosis and treatment regimens. That resulted in a sharp decline in mortality and morbidity. Healthier workers contributed to a remarkable economic growth, which was unprecedented in the world. Furthermore, the health infrastructure built for tuberculosis served as the basis for meeting changing health needs, such as control of non-communicable diseases (NCD). Mass screening originally designed for tuberculosis was used for early detection of hypertension, which was the main risk factor for brain hemorrhage and replaced tuberculosis as the leading cause of death in 1951.

This success story was convincing enough for Japanese leaders and politicians to engage themselves in global health cooperation. During the period of the economic bubble in Japan from 1986 to 1991, Japanese ODA was greatly expanded, which reaffirmed its "soft power" in foreign policy. Meanwhile, reflecting the end of the cold war, a new paradigm was sought globally. As a nation with a constitutional commitment to renounce war, Japan welcomed and promoted the new paradigm of international cooperation, from "security against war" to "human security", which addresses both "freedom from fear of war and other insecurity issues" and "freedom from want of better health and other human conditions" for all people. Human security became the principal value of Japanese diplomacy, and naturally Japan started to voice proposals for global health. At the 1998 Birmingham Summit, then Prime Minister Hashimoto proposed several steps to improve the effectiveness of international cooperation against parasitic diseases. In 2000, the Kyushu-Okinawa G8 Summit adopted the Okinawa Infectious Diseases Initiative, which led global fights against three major infections; HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. In every subsequent G7/8 summit hosted by Japan, health was on the agenda in head of state meetings. For example, the G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit in 2008 addressed the importance of health systems to support disease control activities. With this background, Japan welcomed sustainable development goals (SDGs), and the Prime Minister personally expressed his commitment repeatedly at the United Nations (UN) and in his contribution to the Lancet (13). The G7 Iseshima Summit in 2016 was the first summit meeting after the adoption of SDGs at the UN. The leaders addressed universal health coverage (UHC) as an approach for global health strategies for both communicable and non-communicable diseases under the SDGs framework. At the same time, they emphasized that health systems and UHC are the needed infrastructure to tackle health emergencies such as epidemics, which have been viewed as an increased risk in the interconnected world. The health topics at the summits had expanded from communicable diseases control to a more inclusive approach such as health systems and UHC, which is the course that Japan had taken with not only many successes but also bitter lessons. The Japanese experience can be useful for other nations, particularly Asian countries, which are experiencing a similar course of development and foreseeing rapid aging of their populations.

At the same time, Japanese politicians and business leaders have become more sensitive about the shrinking domestic market due to population aging and decline, and recognize the need to cultivate new industries beyond the production of consumer goods. Advisers to the Prime Minister identified the time gap of population aging among nations as business opportunities for health- and aging-related industries. Being a forerunner in population aging, Japan has been developing systems and technologies for the "silver" market, and hence may have a relative advantage. The linkage of domestic health and technology with global needs and issues as well as business is being formulated. To facilitate such transformation, The Health and Medical Strategy Promotion Act was promulgated in May 2014, which led to the establishment of Headquarters for Healthcare and Medical Strategy (hereinafter referred to as "Headquarters") in June 2014. The Headquarters served as an engine of coordinated policy, and the Cabinet approved the Healthcare Policy in July 2014, including a sentence "Healthcare Policy shall promote overseas activities of the healthcare sector by building mutually beneficial relationships with foreign countries, especially in the fields of medicine and long-term care". In addition, in preparation for the new paradigm of international cooperation beyond the millennium development goals (MDGs), the Headquarters approved the Basic Design for Peace and Health (Global Health Cooperation) in September 2015. The Basic Design emphasizes the importance of UHC and our commitment to SDGs. With this background, the Asia Health and Wellbeing Initiative (AHWIN) (14) was launched in 2016 with wide participation by public and private entities in Japan and international collaborators.

Japan's engagement in global health

The forum for Japanese health diplomacy was G7/G8 summits and multi-lateral UN agencies such as WHO, mainly on the basic framework of human security and SDGs. However, the global environment changed with the emergence of other groups such as BRICs, and G7 leadership also changed the global picture of engagement of G20 countries. The USA and the UK, which had been generous donors in the past, are paying more attention to their domestic issues, while the relative position of Japan and Germany in global health has gained more weight. Also, UHC involves non-health sectors, particularly the Ministry of Finance, private sectors and communities. From this perspective, Japan has started to expand collaboration with the World Bank group in establishing global financing facilities for health and nutrition for mothers and children, as well as pandemic emergency financing facilities. Such collaboration is being expanded to the Regional Banks such as the Asia Development Bank. Also, Japan's stewardship in organizing the G20 Meetings has several characteristics, including head of state meetings including both finance and health ministers, and a separate health minister meeting focusing on UHC, aging and emerging infections including antimicrobial resistance. The series of meetings and communiques left a legacy of serious involvement of G20 in global health as well as its own domestic issues.

In the World Health Organization (WHO), the new Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Gehbreyesus was appointed in July 2017 by direct voting of all member states. He started to transform WHO into the "engine" to accelerate the achievement of SDG3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, through the 13th General Programme of Work (15) (GPW13). The GPW13 sets the targets of triple billion by 2023: one billion more people benefit from UHC; one billion more people have better protection from health emergencies, and one billion more people enjoy better health and well-being. The main pillar of the triple billion is UHC which is defined in one of the 13 targets under SDG3. Each goal of SDGs has a set of targets and indicators for monitoring. Target 3.8 under SDG3 states "Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all". The legitimacy of the UN comes from the approval of the heads of states gathered in the UN by the General Assembly's formal adoption of the SDGs in September 2015. Hence, in the next few years, all global health initiatives will link with the SDGs to justify their legitimacy, and Japan is committed to engage in both domestic and international activities.

Recognition of social determinants of health challenges and mitigation through SDGs/UHC

Commitment to SDGs urged Japan to review critically domestic challenges; for example, health gaps that were difficult to recognize in Japan. Under the post-war regime, the bipartisan political agenda was to generate and maintain a thick middle class layer, and the idea of social gaps and their linkage with health conditions tended to be rejected. However, the long economic slump after the economic bubble crisis together with globalization diminished traditional life-long full-time employment, and blue color jobs were increasingly taken up by Asian neighbors. Also, there were significant changes in the family and its value. Under such a social environment, the Japanese political climate became fluid, except the Koizumi Cabinet (2001-2006) which enjoyed populist support. However, Koizumi's market-oriented approach fueled the demand for fundamental social changes, leading to social movement that brought landslide victory for the opposition party, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), in 2009. The DPJ raised many untouched issues such as poverty among young parents. The Party promised drastic overhaul of the county and attracted initial support. However, due to the rapid ascension of the Party, the leadership lacked skill and experience in running the government. Handling of the 11 March 2011 Tōhoku earthquake/tsunami and nuclear accident highlighted their weakness in governance. Eventually, they lost the general election in 2012. During the period of DPJ rule, evidence such as health disparity and social determinates of health was accumulated. Thereafter, the Liberal Democratic Party regained power and gave priority to economic revitalization, but did not forget the need to address social issues caused by aging and its consequences.

If we look at healthy longevity, Japan has a national health promotion strategy endorsed by the Cabinet since 1978 (revised in 1988). The earlier strategy emphasized the life-course approach, early detection of major NCDs and health promotive activities. The third version was renamed Health Japan 21 and was launched in 2000 with a clear aim of extending a healthy life expectancy. However, the progress report released in 2011 showed that out of 59 targets, only 16.9% were accomplished, 42.4% showed some progress, 23.7% were unchanged and 15.3% deteriorated. The unchanged or worsened targets include decreases in prevalence of metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, and diabetic complications, and the number of steps walked per day. These results raised alarm. The second version of Health Japan 21 (16) issued in 2012 clearly states that the overarching objectives of the second version were to improve healthy life expectancy and narrow health gaps among prefectures (difference in lifespan of two years for men and 2.7 years for women). Then it urged national policies in the following areas: prevention of onset and progression of NCDs, maintaining functions for social wellbeing, cultivating an environment to support health maintenance, and improving lifestyle and social environment for nutrition, exercise, rest, alcohol consumption, smoking, and oral health.

After the turn of the century, the bipartisan political agenda has been the sustainability of social security; first pension, followed by medical insurance, and finally the long-term care insurance scheme. After several reform attempts of individual components, it was recognized that the individual approach had limitations and all components should be reviewed comprehensively. Also, there is broad consensus that our UHC would not be sustainable in the face of increasing senior citizens, declining workforce and increasingly intensive and costly care, as illustrated by the National Council of Reform of Social Security Report (11). The report proposed systematic and comprehensive reform across pension, medical insurance, long-term care insurance and support for child care. According to the Report, the government is moving to ensure universal coverage of client-centered comprehensive health, medical and nursing care support at the community level. This requires significant transformation of service provisions. For example, for a community with a high proportion of senior citizens, acute care service is likely over-supplied while services for chronic illness and rehabilitation may remain under-supplied. All prefectures are mandated by the revised Medical Care Act to plan and transform service provisions ahead of 2025 when the baby boomers become over 75.

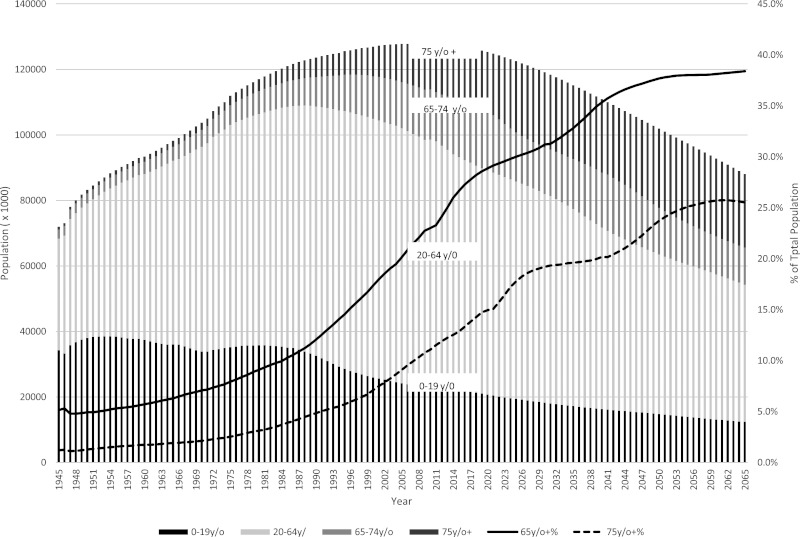

However, aging challenges will continue. As illustrated in Figure 3, the absolute number of senior citizens over 65 will reach a peak around 2042 when the sons or daughters of baby boomers become over 65. The ratio of senior citizens will continue to increase, but the absolute number will decline. However, the cohort of new seniors will be entirely different from previous generations. The likelihood of them being single and part-time workers before retirement will be much higher than the previous generation. The social determinants of health will matter very much because this generation may be disadvantaged in social capital.

Figure 3.

Changes of age groups in Japan. Data source: http://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-zenkoku/j/zenkoku2017/pp_zenkoku2017.asp http://www.ipss.go.jp/ppzenkoku/j/zenkoku2017/db_zenkoku2017/db_s_suikeikekka_1.html

The ways forward: review and comments on recent policy

Prime Minister Abe was in office for 2,616 days at the end of February 2019 and became the second longest serving prime minister in post-war Japan, after Mr. Eisaku Sato who served 2,798 days. His priority for domestic policy is economic revitalization and active measures against aging and low birthrate. Moreover, he views these also from an international perspective, particularly Asia where rapid aging is progressing. In this context, the Basic Principles of the Asia Health and Wellbeing Initiative launched in 2016 was revised in 2018 (14). The underlying philosophy is to enhance cooperation to meet the common challenges of aging by i) sharing Japanese experience (both positive and negative), ii) expanding services with the concept of UHC, iii) accepting care workers to train in Japan who will return home to serve their own aging populations, and iv) R&D taking advantage of Japanese health services and products. This initiative is coordinated by the Cabinet Office, and inter-ministerial works have begun. For example, to accept more care workers, the Immigration Act was amended in 2018 to expand the target from care for the elderly to broader aspects of services and products that support long life, including housing and food.

As describe above, the Cabinet Office launched the Headquarters in May 2016 aiming to lead implementing the SDGs both domestically and internationally. Furthermore, the initiatives include establishment of the SDGs Promotion Roundtable Meeting, where a wide range of stakeholders (including government, NGO/NPOs, experts, private sectors, international organizations and domestic organizations) engage in constructive dialogue. Business communities also participate because they see tremendous opportunities. Echoing such government initiatives, the Japan Business Federation launched Society 5.0 for SDGs (17) with broad participation by business communities.

Synergetic efforts participated in by both public and private sectors have been started to address both domestic and international health challenges. Such spirit of public-private partnership to achieve win-win relations is a rare phenomenon in Japan, and is anticipated to create new value out of collaboration beyond social/ corporate responsibilities. SDGs serve as a catalyst for collective efforts toward sustainable development and surely will occupy a central position in future health agendas in Japan and beyond.

References

- 1. Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. The Ageing Society: Current Situation and Implementation Measures FY 2017. Annual White Paper on Ageing Society, 2018. https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/2018/pdf/c1-1.pdf (accessed March 10, 2019).

- 2. Ikegami N, Yoo BK, Hashimoto H, Matsumoto M, Ogata H, Babazono A, Watanabe R, Shibuya K, Yang BM, Reich MR, Kobayashi Y. Japanese universal health coverage: evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet. 2011; 378:1106-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diamond J. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Penguin Books, 2011; pp.522-523, ISBN 978-0-241-95868-1. [Google Scholar]

- 4. The World Bank. GDP per capita (current US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=JP (accessed March 10, 2019).

- 5. Ikegami N, Campbell JC. Medical care in Japan. N Eng J Med. 1995; 333:1295-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olivares-Tirado P, Tamiya N. Trends and Factors in Japan's Long-Term Care Insurance System. Springer, 2014; pp.15-42, ISBN: 978-94-007-7874-0. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Japanese Law Translation. Long Term Care Insurance Act, Act No. 123 of December 17, 1997. http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?re=2&ky=ask&ia=03&page=13&la=01 (accessed March 10, 2019).

- 8. Elderly Health Bureau. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Briefing material: long-term care insurance system in Japan. https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2018/10/20181023010/20181023010-4.pdf (accessed March 10, 2019) (in Japanese).

- 9. Hideki Komatsu. Collapse of Medical System (in Japanese). Asahi Shinbun Publishing Co. 2006, ISBN:978-4022501837. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ministry of Finance, Government of Japan. Highlights of the Draft FY2018 Budget. https://www.mof.go.jp/english/budget/budget/fy2018/01.pdf (accessed March 10, 2019).

- 11. Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Report of National Council of Reform of Social Security on the roadmap of passing down the sustainable social security system for the next generations, August 6, 2013. http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/kokuminkaigi/pdf/houkokusyo.pdf (accessed March 10, 2019) (in Japanese).

- 12. Shimao T. Fifty years of research on tuberculosis. Lessons I have learnt during 50 years and topics to be investigated in the future. Kekkaku. 2000; 75:483-491. (in Japanese with English Abstract) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abe S. Japan's vision for a peaceful and healthier world. Lancet. 2015; 386:2367-2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cabinet Office. The Basic Principles of the Asia Health and Wellbeing Initiative. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/kenkouiryou/en/pdf/basic-principles.pdf (accessed March 10, 2019).

- 15. World Health Organization. Draft thirteenth general programme of work 2019-2023. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_4-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed March 10, 2019).

- 16. National Institute of Health and Nutrition. Health Japan 21 (the second term). http://www.nibiohn.go.jp/eiken/kenkounippon21/en/kenkounippon21/genjouchi.html (accessed March 10, 2019).

- 17. Japan Business Federation. Society 5. 0 Co-creating the future. http://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2018/095_proposal.pdf (accessed March 10, 2019).