We congratulate Drs Han and Shah on their report of stone extractions using a SpyGlass retrieval basket (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Mass, USA).1 They were able to successfully remove difficult-to-approach and/or impacted bile and pancreatic duct stones in 5 patients. We would like to suggest another potential scenario where cholangioscopy/mini-basket technology can be helpful.

A 39-year-old white woman was referred for management of choledocholithiasis during pregnancy. She had presented to the referring facility 4 months earlier with cholangitis; an MRCP showed a single bile duct stone. During ERCP, the stone could not be retrieved after sphincterotomy. A double-pigtail bile duct stent was placed to ensure drainage. She underwent cholecystectomy the following day with plans for a postoperative outpatient ERCP and further attempts at endotherapy. However, several weeks later and before a second ERCP, it was discovered that she was pregnant.

The patient was referred to our facility with a 17-week intrauterine pregnancy for a second ERCP. Hooding periampullary folds and the previously placed double-pigtail stent precluded clear views of the intraduodenal segment of the bile duct. The pigtail stent was exchanged for a short 5F stent, and a needle knife was used to extend the sphincterotomy over the stent so that bile duct lumen could be visualized. The SpyScope (Boston Scientific) was advanced over a guidewire into the bile duct and a single stone was clearly seen (Fig. 1). The mini-basket sheath was advanced just proximal to the stone, then opened. Upon withdrawing the cholangioscope distally (Fig. 2), the stone was easily captured in the mini-basket (Fig. 3). The SpyScope and mini-basket were then retrieved into the duodenum (Fig. 4). Fluoroscopy was not used at any point during the procedure. The patient tolerated the procedure well. Preprocedure and postprocedure fetal heart tones were normal.

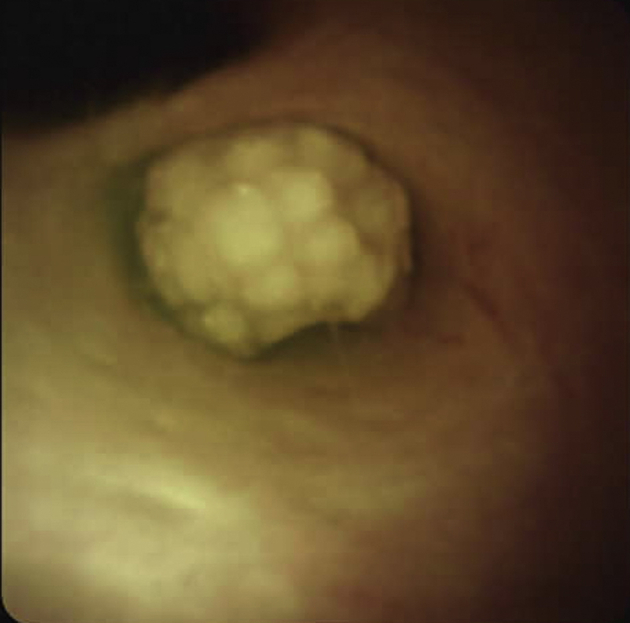

Figure 1.

Direct visualization of bile duct stone via cholangioscopy.

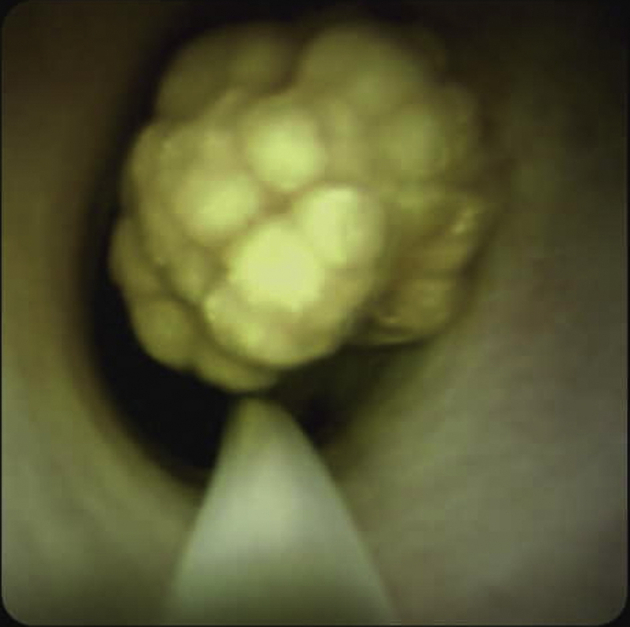

Figure 2.

Mini-basket sheath advanced proximal to stone.

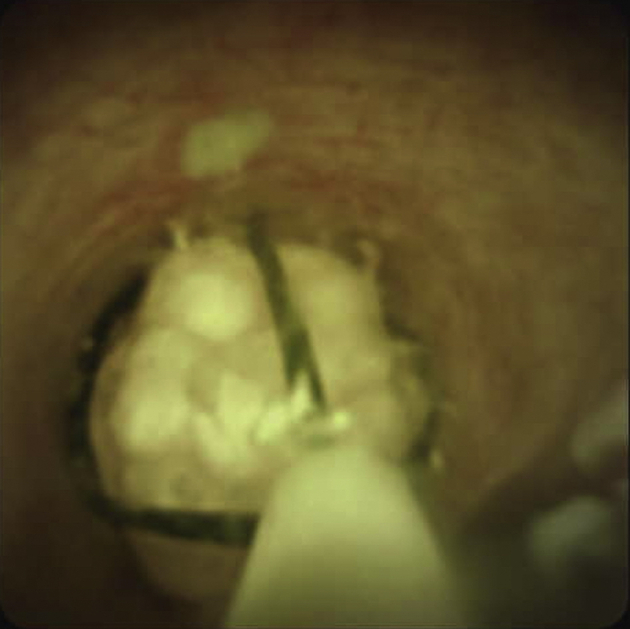

Figure 3.

Capture of stone in mini-basket under direct vision.

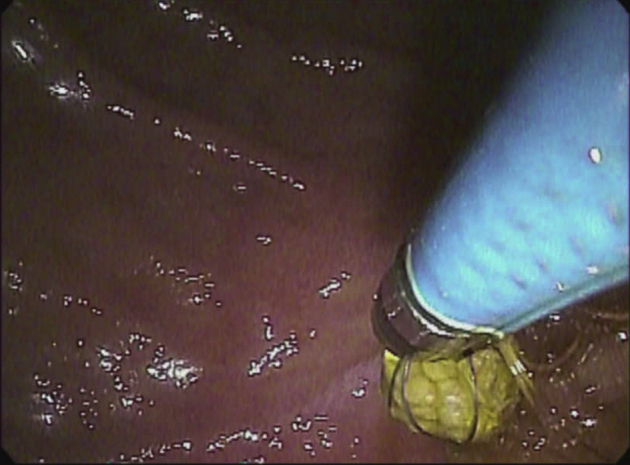

Figure 4.

Captured stone delivered into duodenum.

Challenges related to performing ERCP without radiographic assistance include cannulation of intended duct and confirmation of ductal clearance. We reported the largest series to date of nonradiation ERCP in 2003,2 and for almost 20 years now we have performed all ERCPs on pregnant patients without the use of any fluoroscopy. We reported on the use of cholangioscopy during pregnancy to confirm ductal clearance in 2008.3 The utility of the SpyGlass retrieval basket to capture and retrieve stones under direct vision addresses one of the challenges associated with nonradiation ERCP during pregnancy.

As Drs Han and Shah discussed, the vast majority of bile duct stones can be treated by conventional techniques. Occasionally, with large stones and/or those in difficult locations or if impacted (eg, Mirizzi syndrome, hepatolithiasis), cholangioscopy with intraductal lithotripsy will be required. We suggest that cholangioscopy with mini-basket technology should also be considered as an option for confirmation and clearance of bile duct stones during pregnancy.

Disclosure

All authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Han S., Shah R.J. Cholangioscopy-guided basket retrieval of impacted stones. VideoGIE. 2020;5:387–388. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarnasky P.R., Simmons D.C., Schwartz A.G. Safe delivery of bile duct stones during pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2100–2101. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelton J., Linder J.D., Rivera-Alsina M.E. Commitment, confirmation, and clearance: new techniques for nonradiation ERCP during pregnancy (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]