Abstract

Loiasis is a filarial disease endemic to areas of Central and West Africa. We present a case of Loa loa microfilaremia in a patient with HTLV-1-related adult T-cell lymphoma. This case may suggest the possible role of cellular immunity in controlling microfilaria burden.

Keywords: HTLV-1, Loa loa, loiasis, microfilaremia

Loiasis is a filarial disease endemic to areas of Central and West Africa. We present a case of Loa loa microfilaremia in a patient with HTLV-1-related adult T-cell lymphoma. This case may suggest the possible role of cellular immunity in controlling microfilaria burden.

A 32-year-old man presented to a Canadian hospital with a 3-week history of diffuse lymphadenopathy, subjective fevers, and weight loss of 8 kilograms. He had emigrated from Nigeria to Canada 4 years before presentation. The patient grew up in rural Southwestern Nigeria. His past medical history was notable for chronic hepatitis B and previous malaria treated in Nigeria. He did not smoke, drink, or use recreational drugs. He had no pets, no recent sick contacts, and had not returned to Nigeria since immigrating. He was in a monogamous relationship with his wife and worked a desk job.

On presentation, vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination revealed extensive lymphadenopathy with 2- to 3-centimeter mobile nontender lymph nodes throughout his cervical, axillary, and inguinal areas. Abdominal examination demonstrated enlarged and palpable liver and spleen, protruding 9 and 4 centimeters beyond the costal margins, respectively. No angioedema or rash was present. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurologic examinations were unremarkable.

Initial complete blood count was within normal limits with normal eosinophils and lymphocytes. Computed tomography of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated diffuse lymph node enlargement and hepatosplenomegaly suggestive of a lymphoproliferative disorder. Peripheral blood flow cytometry demonstrated T-cell population predominance, consistent with a mature T-cell lymphoma. Human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV)-1/2 serology was positive. Human T-cell leukemia virus-1 was confirmed because initial HTLV-1 provirus viral load was 77 074 copies per 100 peripheral blood mononuclear cells and HTLV-2 was not detected. Bone marrow biopsy demonstrated normocellular marrow with morphological and immunophenotypical evidence of a mature T-cell lymphoma with chromosomal aberrations of 1q, 4q, 5q, 6q, and 10p. Pathology of an excised peri-parotid lymph node further confirmed this diagnosis. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus and toxoplasmosis was negative. Peripheral blood film for Plasmodium was negative. Serological testing for Strongyloides stercoralis and Schistosoma was negative. Serological testing for filariasis was negative using an enzyme immunosorbent assay created from antigens extracted from Brugia malayi nematodes. This test is known to be cross-reactive with many filarial species, including Loa loa, and thus is the assay available in Canada for the serologic diagnosis of Loiasis.

The patient was started on DA-EPOCH antilymphoma therapy with etoposide (50 milligrams/meter2 per day), doxorubicin (10 milligrams/meter2 per day), and vincristine (0.4 milligrams/meter2 per day) on days 1 to 4, with the addition of 1 dose of cyclophosphamide (750 milligrams/meter2 per day) on day 5. Prednisone (120 milligrams orally daily) was provided from days 1 to 5. With the initiation of anticancer therapy, the patient was started on tenofovir (300 mg orally once daily) to prevent hepatitis B reactivation as well as lamivudine (300 mg orally once daily) and raltegravir (400 milligrams orally twice daily) to diminish HTLV-1 viral replication [1]. Allopurinol prophylaxis for tumor lysis and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis were started. Follow-up computed tomography, performed 10 days after chemotherapy initiation, demonstrated significant improvement of lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. The patient’s subjective fever and malaise improved.

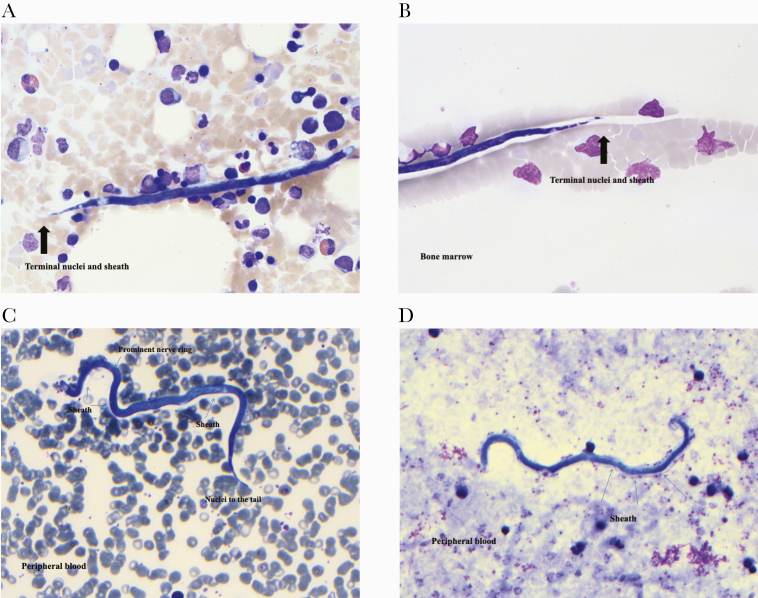

Giemsa staining of the peripheral blood and the original bone marrow biopsy before steroid and antilymphoma therapy incidentally demonstrated sheathed microfilaria (Mf) with nuclei extending to the tip of the tail, consistent with Loa loa (see Figure 1). Visualization of the peripheral blood demonstrated the undulating movement of erythrocytes displaced by Loa loa Mf (see online video in the Supplementary Material). Although the video of unstained peripheral blood did not allow for confirmation of Loa loa microfilariae, the Giemsa stain of the peripheral blood and bone marrow both demonstrate nematodes with the sheath, size, and tail-tip nuclei of Loa loa. Other nematode mimics, with different morphologic characteristics, were not detected. An estimation of parasitemia was based on the total number of parasites detected on 10 thick blood films, with each thick film containing 10 µL blood. It was determined that there were approximately 6900 Mf/mL before Loiasis treatment.

Figure 1.

Loa loa microfilaria seen on Giemsa stain of the peripheral blood and bone marrow biopsy before steroid and chemotherapy administation. Arrows indicate important morphologic characteristics such as the presence of nuclei in the tip of the tail as well as the translucent halo-like sheath, unstained by Giemsa, that extends from the tail. In one image, the sheath partially obscures the adjacent erythrocyte. The presence of nuclei in the tip of the tail differentiates Loa loa from other sheathed microfilariae from the genera Wurchereria and Brugia.

The patient was first treated with albendazole (200 mg orally twice daily) for 21 days. Two months later, the patient was given diethylcarbamazine (DEC) with a graded dosing schedule to complete a 21-day course (50 milligrams orally on day 1, then 50 milligrams orally 3 times a day on day 2, then 100 milligrams orally 3 times a day on day 3, followed by 200 milligrams orally 3 times daily for 18 days). Although the use of albendazole at least 3 months before DEC is indicated to prevent DEC from triggering fatal encephalopathy among individuals with Mf levels greater than 20 000 Mf/mL, the above treatment approach was undertaken due to the patient’s immunosuppression and safe Mf levels [2, 3]. Although Mf levels were not measured between albendazole and DEC, no Loa loa microfilariae were detected on peripheral blood films performed after combination treatment. The patient had always remained asymptomatic from his Loiasis.

The patient continued on the regimen of tenofovir, lamivudine, and raltegravir with diminishing HTLV-1 provirus levels, decreasing to 758 copies per 100 peripheral blood mononuclear cells 12 months after initial presentation. Unfortunately, 18 months after initial presentation, the patient succumbed to a relapse of his underlying lymphoma.

Patient Consent Statement

The patient’s consent for case presentation and publication was obtained when the patient was alive. His case was presented at local rounds at that time and he was aware of a plan for journal publication. Unfortunately, the patient died 2 years ago. This conforms to Canadian standards and those of the University of Manitoba.

DISCUSSION

Loiasis is a filarial disease endemic to Central and West Africa and is transmitted by the Chrysops fly [4]. In areas where Loiasis, onchocerciasis, and lymphatic filariasis are coendemic, Loa loa constrains the control of onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis via mass drug administration due to the severe and sometimes fatal adverse events that ivermectin may trigger among individuals with elevated Loa loa microfilaremia [3, 5]. This phenomenon has led to a “test-and-not-treat” strategy for the control of onchocerciasis in coendemic areas [2]. Although Loiasis has traditionally been considered a benign condition, high-grade Loa loa microfilaremia is increasingly recognized to be associated with mortality [6].

Upon biting infected individuals, Chrysops flies ingest Loa loa microfilariae. Loa loa parasites may be transmitted to other human hosts from a second bite of the infected Chrysops fly. Although microfilaremic individuals drive ongoing Loa loa transmission, only a minority of Loa loa-infected individuals are microfilaremic [7]. A significant familial susceptibility for microfilaremia, strongest between mothers and children, has been described; however, no genetic locus has been identified [8]. Microfilaremia is also associated with a relative lack of T-cell response [9].

Human T-cell leukemia virus-1 is notorious for its association with disseminated strongyloidiasis via its induction of Th1-responsiveness at the expense of a Th-2 response [10]. Strongyloides stercoralis is a nematode within the same Chromadorea class as Loa loa. Human T-cell leukemia virus-1 is transmitted from mother to child, predominantly through breast milk [11].

In this case report, the incidental finding of Loa loa Mf in a patient with HTLV-1 may be purely coincidental. Many individuals from Loa loa-endemic areas may have Mf in their peripheral blood and possibly in their bone marrow. Loa loa-endemic areas of West Africa also have elevated rates of HTLV-1, increasing the likelihood of both diseases coincidentally occurring in one individual [12].

CONCLUSIONS

However, to our knowledge, no studies of HTLV-1 and Loa loa exist. Because testing for HTLV-1 does not routinely occur among individuals with Loiasis, it remains possible that HTLV-1 may play a role in the familial aggregation of individuals with Loa loa Mf. Further studies comparing Loa loa Mf levels of individuals with and without HTLV-1 infection are warranted to better elucidate the underlying host factors responsible for Loa loa microfilaremia and subsequent transmission.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Kim and the Canadian National Laboratory for HIV Reference Services for their quantification of human T-cell leukemia virus-1 provirus.

Author contributions. All authors have read and approved the submission of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Seegulam ME, Ratner L. Integrase inhibitors effective against human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:2011–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kamgno J, Pion SD, Chesnais CB, et al. A test-and-not-treat strategy for onchocerciasis in Loa loa-endemic areas. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:2044–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Report of a Scientific Working Group on serious adverse events following Mectizan(R) treatment of onchocerciasis in Loa loa endemic areas. Filaria J 2003; 2 Suppl 1:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kelly-Hope L, Paulo R, Thomas B, et al. Loa loa vectors Chrysops spp.: perspectives on research, distribution, bionomics, and implications for elimination of lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Parasit Vectors 2017; 10:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Demanga-Ngangue, et al. Serious reactions after mass treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin in an area endemic for Loa loa infection. Lancet 1997; 350:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chesnais CB, Takougang I, Paguélé M, et al. Excess mortality associated with loiasis: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garcia A, Abel L, Cot M, et al. Genetic epidemiology of host predisposition microfilaraemia in human loiasis. Trop Med Int Health 1999; 4:565–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eyebe S, Sabbagh A, Pion SD, et al. Familial aggregation and heritability of Loa loa microfilaremia. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 66:751–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baize S, Wahl G, Soboslay PT, et al. T helper responsiveness in human Loa loa infection; defective specific proliferation and cytokine production by CD4+ T cells from microfilaraemic subjects compared with amicrofilaraemics. Clin Exp Immunol 1997; 108:272–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Porto AF, Neva FA, Bittencourt H, et al. HTLV-1 decreases Th2 type of immune response in patients with strongyloidiasis. Parasite Immunol 2001; 23:503–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li H-C, Biggar RJ, Miley WJ, et al. Provirus load in breast milk and risk of mother-to-child transmission of human T lymphotropic virus type I. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:1275–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kengne M, Tsata DCW, Ndomgue T, Nwobegahay JM. Prevalence and risk factors of HTLV-1/2 and other blood borne infectious diseases among blood donors in Yaounde Central Hospital, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J 2018; 30:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.