Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori, a 2 × 1 μm spiral-shaped bacterium, is the most common risk factor for gastric cancer worldwide. Clinically, patients presenting with symptoms of gastritis, routinely undergo gastric biopsies. The following histo-morphological evaluation dictates therapeutic decisions, where antibiotics are used for H. pylori eradication. There is a strong rational to accelerate the detection process of H. pylori on histological specimens, using novel technologies, such as deep learning.

Methods

We designed a deep-learning-based decision support algorithm that can be applied on regular whole slide images of gastric biopsies. In detail, we can detect H. pylori both on Giemsa- and regular H&E stained whole slide images.

Results

With the help of our decision support algorithm, we show an increased sensitivity in a subset of 87 cases that underwent additional PCR- and immunohistochemical testing to define a sensitive ground truth of HP presence. For Giemsa stained sections, the decision support algorithm achieved a sensitivity of 100% compared to 68.4% (microscopic diagnosis), with a tolerable specificity of 66.2% for the decision support algorithm compared to 92.6 (microscopic diagnosis).

Conclusion

Together, we provide the first evidence of a decision support algorithm proving as a sensitive screening option for H. pylori that can potentially aid pathologists to accurately diagnose H. pylori presence on gastric biopsies.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Deep learning, Convolutional neural networks, Gastric cancer prevention, Screening, Helicobacter pylori

Background

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium, measuring 2–4 μm in length and 1 μm in width, usually presented in a spiral-shaped structure [1–3]. Clinically, H. pylori has been classified as a WHO class 1 carcinogen and represents the most common cause of gastric cancer worldwide [4, 5]. Importantly, the vast majority of all gastric cancers outside the cardia arise within H. pylori infected gastric mucosa [6, 7]. It has been shown that eradication of H. pylori can reduce the risk of gastric cancer in both retrospective-, as well as prospective clinical trials [8–10]. Although the incidence of gastric cancer itself is declining in Western countries, the disease is usually diagnosed in late stages, where individuals face a dismal prognosis—due to limited therapeutic options [11–13]. Meanwhile, systematic testing for H. pylori and corresponding therapeutic interventions have been established [14, 15]. However, the prevalence of H. pylori infection differs greatly between 20 and 80% within populations [16].

Advances in the field of hardware components, as well as the availability of large amounts of data, have allowed the field of artificial intelligence to rapidly grow [17]. Lately, these technologies have been successfully applied to improve diagnostic procedures in the medical field [1–3].

Therefore, we aimed to (1) design a deep learning based decision support algorithm that highlights H. pylori bacteria in image regions of gastric biopsies samples that are routinely tested for H. pylori presence and (2) validate this algorithm both on Giemsa stains and regular H&E stains comparing with microscopic diagnosis, immunohistochemistry and PCR.

Methods

Digitalization of whole slide images and quality control

Modified Giemsa and regular H&E stained slides were scanned using a NanoZoomer S360 (Hamamatsu Photonics) whole-slide scanning device at 40X magnification, as well as a DP200 slide scanner (ROCHE Diagnostics) at 40X. The slides were then evaluated for image quality and included within the validation cohort, if at least 50% of the tissue allowed a distinction of cell types. The evaluated tissue had to include at least 50% of gastric tissue to be included. Therefore, biopsies that primarily included intestine or esophageal tissue were not included.

Detection of H. pylori: image processing

Our approach consists of first localizing areas of H. pylori presence (herein referred as H. pylori hot spots) using image processing, and then cropping the hot spots into 224 × 224 patches and classifying them with a deep neural network. H. pylori typically exists inside and around glandular structures that can be described as white regions image regions inside the gastric tissue (Fig. 1b). To localize these regions, we downscaled the slide by a scale of × 32 in each axis, applied Otsu thresholding on the saturation channel in the HSV color space, then performed erode/dilate morphological operations to create a mask with the white regions. Then we would find the contours of these regions and crop them into non-overlapping patches of 224 × 224. Regions that had an area smaller than 32 pixels were discarded. A typical slide had hundreds to thousands of H. pylori patch candidates. These were then filtered by a classification network to only keep patches that contained H. pylori.

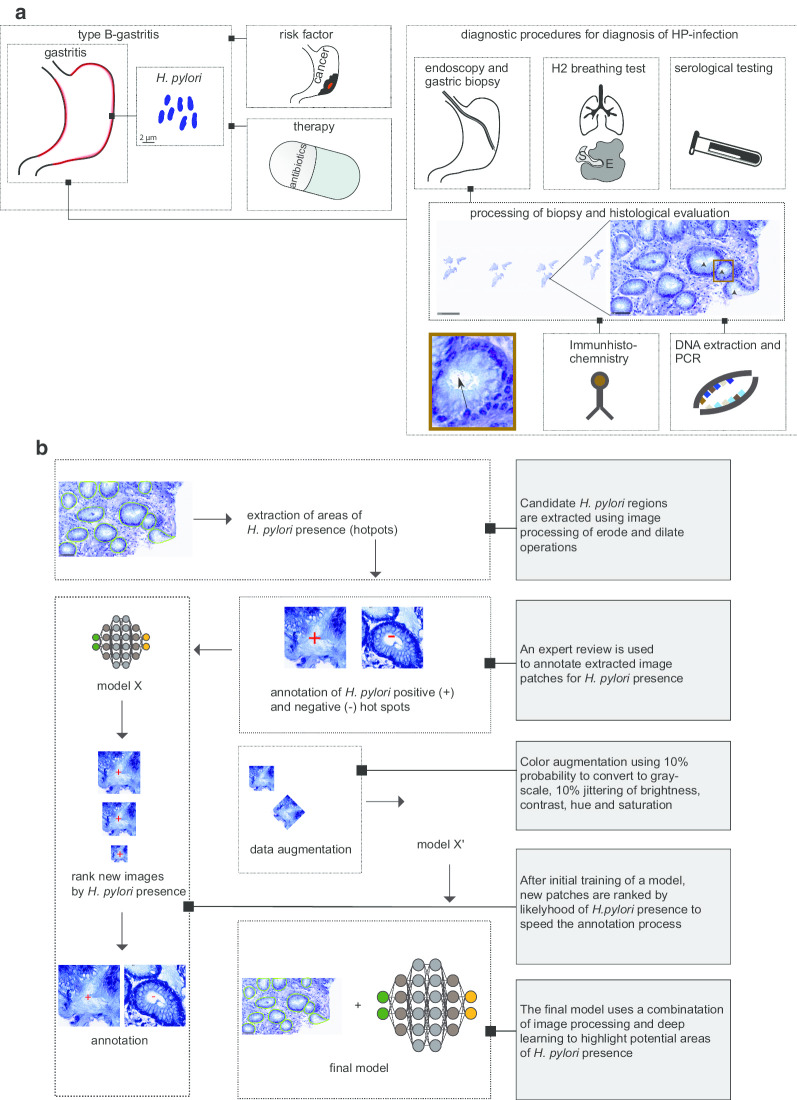

Fig. 1.

Clinical relevance of H. pylori and illustration of strategy to build a model detecting H. pylori. a Illustration of the diagnostic spectrum for type B-gastritis (bacterial gastritis, or H. pylori -gastritis) linked to H. pylori infection. While endoscopic evaluation of the stomach remains, and consequently harvesting gastric biopsies, other diagnostic tests, such as H2 breathing test and serological testing for H. pylori can be applied but may not differentiate for an active H. pylori infection. The tissue of gastric biopsies can histologically be reviewed, but also further tests can be applied, such as Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which are more sensitive. b Schematic representation of the approach to build a H. pylori classifier. Initially, areas within gastric biopsies of H. pylori presence were extracted (H. pylori hot spots, circled with green). Then, these hot spots were annotated according to their presence or absence of H. pylori, following a training step of an initial model. To further improve the detection sensitivity and specificity, this step was repeated for several times to generate a larger training dataset. The final model was trained containing several thousand H. pylori hot spots. Lastly, data was augmented by using color augmentation

Detection of H. pylori: deep learning

To classify the patches, we trained a compact VGG-style deep neural network [18]. The same network was trained on both Giemsa and H&E slides, in order to improve the generalization of the network on slides with stain variation. The network had 9 convolutional blocks followed by 3 fully connected layers. The first two convolutional layers are pointwise convolutions that help the network generalize on multiple stains [20]. The next two layers had kernel sizes of 7 × 7 and 5 × 5, that increased the receptive field, and the rest had kernel sizes of 3 × 3. The capacity of the network was reduced by scaling the number of features in every layer. The last convolutional layer had the output of only 32 channels. The first two fully connected layers had 1024 channels each, and the last layer has two outputs. We used 50% dropout between the fully connected layers, and batch normalization layers after the ReLU nonlinearity layers in the convolutional part of the network. In addition, we used standard cross entropy as the loss function and weighed the categories by their proportions in the dataset. As an optimizer, we used Adam with default parameters. We used a batch size of × 32, that was split among 4 1080ti GPUs, using the PyTorch framework. To help generalize among different stains, we used aggressive color augmentation. The brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue of every image was randomly jittered with strong portions. We also randomly flipped and rotated the image, then applied random grayscale and local elastic transformations.

Visualization of the convolutional neural network output

Although the network performs classification, we applied a technique to help with the localization of individual H. pylori bodies. We first applied the SmoothGrad technique and averaged the gradients of the category score with respect to noisy input image pixels [21]. The gradient image is then passed to a ReLU gate, to keep only positive gradients. The gradient image was then used as a threshold, and input image pixels that had lower gradients were masked out, in order to only retain pixels that were important for the network decision. The threshold was then set to the 99.8% gradient percentile to keep the top instances. Then, the gradient image was dilated, and we drew contours over connected components to highlight areas that had H. pylori bodies with high confidence.

Training datasets and annotation strategy

An overview of the training dataset can be found in Table 1. Overall, 191 H&E and 286 Giemsa stained slides were used, with a total of 2629 tiles containing for Giemsa 790 and H&E. About 4241 and 1533 tiles without H. pylori -like bacterial structures were used for Giemsa and H&E, respectively.

Table 1.

Corresponding anatomical sites of gastric biopsies being evaluated for both training and validation of the algorithm

| Localisation | Training | Validation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giemsa | H&E | Giemsa | H&E | |

| Antrum | 226 | 145 | 59 | 52 |

| Corpus | 35 | 30 | 17 | 11 |

| Duondenum | 15 | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Cardia | 8 | 12 | 4 | 3 |

| Fundus | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Using the strategy of training an initial model to classify H. pylori hot spots (Fig. 1b), we annotated the whole slide image (WSI), avoiding the need to manually annotate H. pylori regions in slides. First, the H. pylori candidate localization algorithm was applied on every slide, creating thousands of crops on average. Crops from slides lacking H. pylori were automatically labeled as “not H. pylori.” Crops from slides containing H. pylori were labeled in a gallery by pathologists. Since the number of H. pylori may be scarce even in slides that do contain H. pylori, there was a high level of variance between categories that made the annotation challenging. We used an active learning approach, where the dataset was constructed in steps of labeling few hundred crops each time, then a model was trained, and the remaining unlabeled crops were ordered from high to low according to their H. pylori category score. In the next step, the labeling was done on high scoring H. pylori crops, dramatically increasing the rate of encountered H. pylori crops and making the dataset labeling time efficient. This process was stopped when the rate of appearing H. pylori crops was very low, after a few thousand labeled images. The dataset contains more Giemsa slides than H&E slides. Using active learning, we were able to reduce the reviewed crops from nearly a hundred thousand crops (the total number of extracted candidates) to several thousand.

Validation: region of interest review

We used a decision support algorithm approach of showing the top ranked 39 tiles (224 × 224 pixels) of an WSI to an experienced pathologist. We defined H. pylori presence, if at least two bacterial-like and spiral structures were present within an image. In total, the area of the presented fields reflected less than 1% of the area of the whole slide tissue area (Fig. 2b, c).

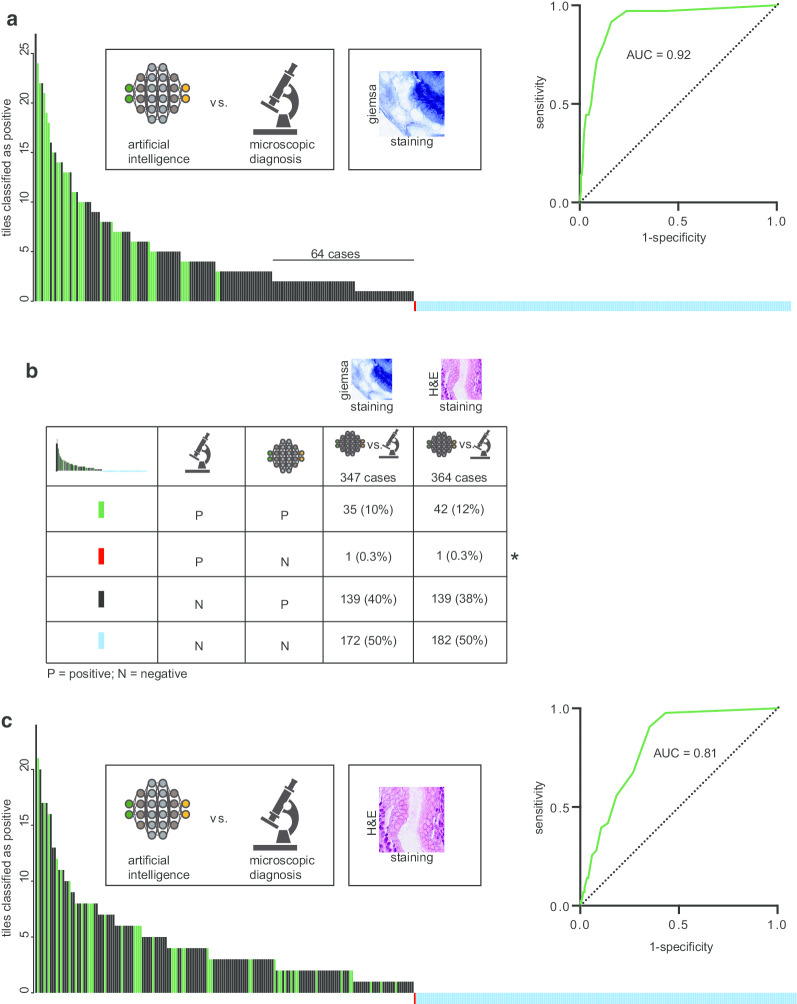

Fig. 2.

Validation strategy of the decision support algorithm. a Visualization of H. pylori detection in both Giemsa and H&E stained images. The green border highlights detected H. pylori bodies that the network correctly classified as H. pylori. b Illustration of the approach of validating the AI algorithm. About 347 Giemsa-stained slides (blue dots on illustrated slide) and 364 H&E slides (red dots on illustrated slide) were used, following an extraction of H. pylori hot spots. Then, the extracted hot spots were classified and ranked by H. pylori presence. The bean like structure of H. pylori is shown to visualize the scale. c The extracted and classified H. pylori hot spots were then annotated for H. pylori presence, as shown by a red box around four of the six tiles. The numbers correspond to an exemplified rank for H. pylori detection. For simplification, only Giemsa pictures are shown, while H&E stains were used for validation as well

Validation: RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry for H. pylori

In a subset of samples with conflicting microscopic diagnosis, despite clear visible H. pylori-like structures, or inconclusive H. pylori status, additional 46 samples were analyzed using PCR. H. pylori was screened with the RIDA GENE® Helicobacter pylori assay (r-biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany). At least one area on a hematoxylin–eosin stained slide was selected by an experienced pathologist (RB, AQ, SK) and DNA was extracted from corresponding unstained 10 µm thick slides of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue by manual micro-dissection. Isolation was performed semi-automatically using the Maxwell® 16 FFPE Plus Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit on the Maxwell® 16 System (Promega, Mannheim, GER) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The RIDA GENE® Helicobacter pylori assay was performed with 5 µl of DNA for each sample independent of DNA concentration and fragmentation on a CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (BIO-RAD, Hercules, California) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Analyses were performed with the corresponding software. As amplification control, an internal control DNA (1 µl) was added to each PCR-Mix of all samples. All samples had to show a positive amplification of the internal control DNA (Additional file 1: Figure S2A). For a reliable detection of H. pylori and the Clarithromycin resistance positive (red curve) and negative controls (black curves) were included into each run (Fig. 2b). Additional file 1: Figure S2C shows the amplification curves for the detection of the clarithromycin resistance. The fluorescence signal for a resistance to clarithromycin had to be more than 20% of the fluorescence signal of the positive control. To determine the sensitivity of this assay, a serial dilution (1:2) of the positive control was performed (Additional file 1: Figure S2D). Discrepant cases were validated with the GenoTypeHelicoDR assay (Hain Lifesciences GmbH, Nehren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with 5 µl of DNA for each sample. Immunohistochemical staining for H. pylori was performed on full tissue sections using the BOND MAX from Leica (Leica, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and a polyclonal anti-H. pylori antibody from Cell Marque™. All stained sections were evaluated by an experienced pathologist (AQ, RB).

Results

Generating an assistive support algorithm to detect Helicobacter pylori on whole slide images

Symptoms of gastritis regularly require an endoscopic evaluation of the stomach. While several diagnostic tests can be applied, histo-morphological assessment of the tissue can be considered a standard procedure in Western countries (Fig. 1a) [4–10]. Clinically, the subtype of bacterial-associated gastritis (Type-B-Gastritis) is linked to infection with H. pylori. Usually, modified stains, such as Giemsa stains, help visualize these bacterial structures for histo-morphological assessment. In addition, H&E stains are performed to evaluate morphological abnormalities.

Therefore, we generated a decision support algorithm that would highlight regions of H. pylori presence on both modified Giemsa stains and regular H&E stains. We applied a combination of image processing and deep learning to extract regions of H. pylori presence, as well as to classify those regions, using a convolutional neural network (CNN) (Fig. 1b). Due to the fact this hybrid approach limits the amount of image information that are processed by a CNN-thereby saving computational resources–it allows the WSI analysis in high resolution to be done within seconds on regular clients. Typically, H. pylori resides in areas that can be described as a white background from an image processing point of view. Thus, we applied a pre-processing step to detect these candidate regions, using a combination of thresholding- and morphological operations on a low-resolution image. We decided to extract all candidate regions and annotate those patches in a gallery as the annotation of H. pylori containing areas is necessary, but time consuming and challenging on WSI (Fig. 1b). We applied an active learning approach on the annotated data, which represents an imbalanced data pool. The images were sorted by their H. pylori scores, allowing high-scoring images to be presented in priority.

In order to overcome the stain variation of histological specimens, we applied aggressive color augmentation on the extracted images for better performance and generalizability. Images were converted to a grayscale with 10% probability and heavy color jittering. In addition, we trained the same network for both H&E and Giemsa stains to further improve generalization across color- and stain variations.

Having generated the final model, we further aimed to understand the decisions of the network. We visualized and highlighted areas in the image that were significant for the network’s output (Fig. 2a). Having shown that the algorithm detects H. pylori bacterial structures on both modified Giemsa stains and regular H&E stains, we validated the algorithm using an independent cohort of gastric biopsies of cases that had not been used for training purpose. Initially, we validated the decision support technology against microscopic diagnosis.

Comparison of Helicobacter pylori detection to microscopic diagnosis

Validation strategy

H. pylori is a small particle of a size of about 2–4 μm, which accounts for one pixel in an image containing about 20 billion pixels in total (Fig. 2b). For the purpose of validation, we applied a selective presentation of tiles that had been extracted and classified by the algorithm, showing less than 1% of the tissue of the whole slide in total. Finally, two board-certified pathologists (expert review) evaluated these tiles for the presence of H. pylori (Fig. 2c). No other information was shown to the pathologists reviewing the tiles for validation.

For modified Giemsa stains, 347 slides were analyzed and compared to microscopic diagnosis (Fig. 3a, b). We defined H. pylori positivity as presence of at least two H. pylori-like bacterial structures within an extracted image. By using this definition, we detected H. pylori in 181 slides, with varying amounts of tiles being positive (Fig. 2a). Based on the amounts of positive tiles, the calculated area-under-the-curve (AUC) was 0.92 for modified Giemsa stains compared against microscopic diagnosis (Fig. 2a). To further provide evidence of the generalizability of the algorithm, we validated the model on regular H&E stains. For this purpose, 364 cases were used and validated against microscopic diagnosis. The AUC for H&E was 0.81 (Fig. 3c). Interestingly, a potential threshold of 2 tiles appeared to increase specificity without decreasing the sensitivity on Giemsa stains (Fig. 3a, Table 2), while this was not the case for H&E stains. Within H&E stains, there were cases found to be positive presenting with only one positive tile (Fig. 3c). In addition, there was one case that was found to be positive with help of histo-morphological diagnosis, but where the decision support algorithm could not reveal tiles containing H. pylori (Fig. 3b, refer to *). In further validation, it was confirmed that this case was H. pylori negative.

Fig. 3.

Validation of the decision support algorithm against microscopic diagnosis. a Bar chart of detection of H. pylori with help of the assistive algorithm, validated against microscopic diagnosis using Giemsa stains. The Y-axis reflects the amounts of detected positive tiles using the algorithm assisted approach. The color code of each bar is shown in legend of (b). c Calculation of area-under-the-curve (AUC) of H. pylori detection for H&E stains validated against microscopic diagnosis

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the validation, in respect to staining and validation techniques

| Parameter (of 87 cases) | Microscope (Giemsa) | Algorithm (Giemsa) | Algorithm (tile based threshold > 2) | Ground truth (IHC/PCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True positive (n) | 13 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| False positive (n) | 5 | 36 | 23 | NA |

| False negative (n) | 6 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| True negative (n) | 63 | 32 | 45 | 68 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 68.4 | 100 | 100 | NA |

| Specificity (%) | 92.6 | 47.1 | 66.2 | NA |

| Disease prevalence (%) | NA | NA | NA | 21.8 |

NA not applicable

Validation of microscopic diagnosis against IHC/PCR

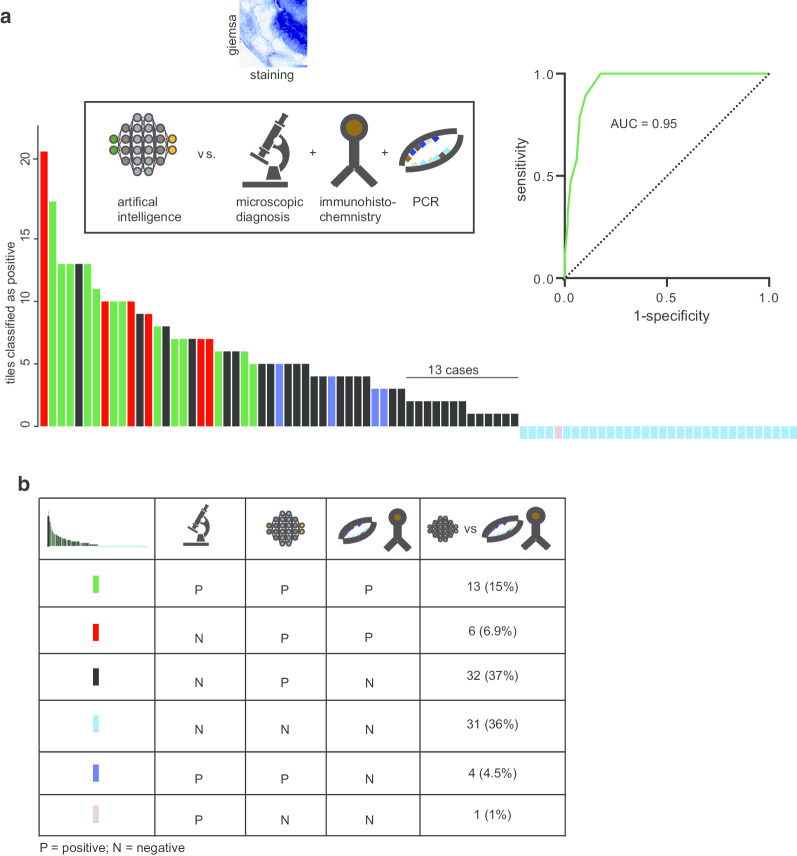

Having shown an initial performance of the algorithm, we applied two more sensitive and independent technologies to allow an additional validation (ground truth) of H. pylori presence on a subset of the cohort that had been initially validated against microscopic diagnosis. Cases with clear and visible H. pylori bodies in Immunohistochemistry (IHC) did not undergo additional PCR testing, while cases uncertain of H. pylori status after IHC, underwent additional PCR testing. 19 cases were confirmed to be H. pylori positive using IHC/PCR in this cohort and only 13 cases were identified as positive microscopically (Fig. 4a, b; Table 2). In addition to the 13 positive cases, 5 cases were identified microscopically as H. pylori positive, but these cases could not be confirmed by IHC/PCR (Fig. 4b, Table 2). Overall, microscopic diagnosis revealed a sensitivity of 68.4% with a specificity of 92%.

Fig. 4.

Validation of the decision support algorithm against microscopic diagnosis and IHC/PCR. a Bar chart of detection of H. pylori with help of the decision support algorithm, validated against microscopic diagnosis, and IHC/PCR using Giemsa stains. The Y-axis reflects the amounts of detected positive tiles using the algorithm. All 32 cases where the assistive approach did not detect H. pylori, underwent an additional PCR testing. The color code of each bar is shown in legend of (b). c Calculation of area-under-the-curve (AUC) of H. pylori detection for H&E stains validated against microscopic diagnosis

Validation of the decision support algorithm against IHC or PCR

Within the set of modified Giemsa stains, a subset of 87 slides was analyzed with the decision support algorithm. Out of 19 H. pylori positive cases that were confirmed by IHC/PCR, assisted approach was able to detect all 19 of them (Fig. 4a, b). Interestingly, the two microscopical positive cases that were detected negative by AI in the initial validation stage using microscopic diagnosis as ground truth were found to be negative by IHC and PCR testing (Fig. 4a, b). Together, an AUC of 0.95 was achieved for the assistive algorithm using Giemsa stains (Fig. 4a), while the sensitivity was 100% and the specificity 47.1% without applying a tile bases threshold (Table 2). Given that the initial validation against microscopic diagnosis showed 64 cases with 2 positive tiles that were found to be negative by microscopic assessment, this could be confirmed by further validating a subset of those cases against IHC/PCR. Indeed, 13 cases with two positive tiles were also negative, highlighting a potential threshold of more than 2 tiles to increase specificity (66.2%, Table 2), without decreasing the sensitivity (Fig. 4a, b).

Discussion

Our approach follows the current regulations of the application of computerized algorithms, which require to visualize the results of a given technology. Those results can then be further evaluated by an expert and therefore be checked for plausibility. With the help of this assistive decision support algorithm, we avoided the black box character of AI. In detail, we did not assign a general category (positive/negative) on whole slide basis. Instead, by using a decision support algorithm that highlights regions of potential H. pylori presence, we were able to increase the sensitivity of H. pylori detection (microscope: 68.4%; decision support algorithm: 100%), and at the same time allowed it to be applied on both H&E and Giemsa stains, strengthening the idea of a more generalized approach.

During the course of this study, Martin et al. [22] published a slightly different approach by applying tissue segmentation of histological specimens of gastric biopsies to identify diseased mucosa. In this study, the gold standard was defined by methods other than PCR, including histological evaluation by a Pathologist. While this approach seems to be intriguing, one may not be able to diagnose cases with less characteristic histology but presence of H. pylori bacteria. In addition, our approach can be operated with limited computational resources because of its architecture and can be applied on both Giemsa and H&E stains.

In addition, several studies have applied deep learning for H. pylori detection on endoscopic imaging data [23–25]. Given that this intervention would not necessarily even require to harvest biopsies and therefore to collect tissue, it appears advantageous. However, within those studies more sensitive testing for the presence of H. pylori, including sequencing based H. pylori detection (PCR), would potentially have provided a definition of H. pylori status of higher sensitivity as a gold standard for evaluating the Computer-Aided-Detection (definition of ground truth). As chronic infection of the stomach displays an important risk factor for malignancies, including mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-lymphoma and gastric cancer, one may argue that harvesting tissue for histological evaluation is a diagnostic necessity. Therefore, it remains to be seen whether endoscopic detection of H. pylori infection using deep learning would result in clinical benefit for individuals.

Technically, the architecture of our algorithm combines both image processing and classification by using a deep neural network. In summary, only relevant image areas (H. pylori -hotspots) are further analyzed by a deep neural network. This design of the algorithm greatly lowers the amount of computational resources that needs to be present to analyze whole slide images for H. pylori presence.

Both image quality and staining quality influence the specificity of the decision support algorithm. Structures, which were found to confuse the network, leading to detection of particles falsely classified as H. pylori, are shown in Additional file 2: Figure S1. Likely, this is due to either other bacterial structures being present on the slide—potentially contaminations of the tissue due to processing of the histological specimens—as well as image quality. Within this study, we included tissues that were processed using standard techniques. For potential clinical application of decision support algorithms to detect H. pylori on regular biopsies, a prior quality check of the specimens might allow to lower the detection rate of either detritus or image artifacts.

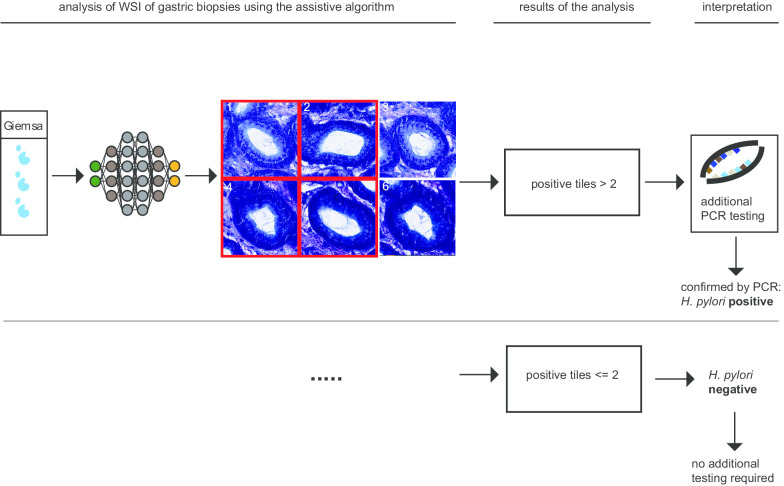

We observed a prevalence of 22% of H. pylori infected individuals within the subset of IHC/PCR validated cases (Table 2). Considering the generalizability of the validation, the specificity might be lower compared to cohorts with a higher disease prevalence. Still, with a sensitivity of 100% for both H&E and specialized Giemsa stains, our approach could potentially be qualified for screening purpose. In addition, the performance of H. pylori detection using Giemsa stains was higher, potentially because the human interactor is trained to identify H. pylori bacterial structures on these stains. In light of the high false-positive rate (41%; 36 out of 87 cases) of the assistive algorithm applied on Giemsa stains (Fig. 4a, b; Table 2), a potential clinical application might require an additional validation step of PCR or IHC diagnosis, if a certain threshold of positive tiles been reached (Fig. 5, Table 2). At the same time, it allows to sensitively declare cases as H. pylori negative, if the decision support algorithm did not detect H. pylori. Potentially, this technology would therefore qualify as a sensitive screening technology. However, because experts will be involved in the decision making, more experience with digitalized images of H. pylori might further increase the specificity of these approaches. Furthermore, image quality and the quality of the stains greatly influence the ability of an observer to specifically recognize H. pylori -like bacteria structures.

Fig. 5.

Potential workflow of a decision support algorithm to detect H. pylori on whole slide images. Processed images undergoing a visual confirmation of H. pylori presence (analysis, results) or either a definite diagnosis of H. pylori absence/presence (interpretation). Cases above a certain threshold (2 in our study) would undergo additional confirmation by PCR testing

Conclusion

Our study highlights a discrepancy between microscopic diagnosis and H. pylori status, using sensitive diagnostic tools, such as IHC/PCR, which provides evidence of cases that are missed using microscopic diagnosis alone. This is in line with previous findings, where H. pylori DNA was found in about 30% of cases that had been diagnosed as H. pylori -negative, based on histo-morphological assessment [26]. Potentially, this further strengthens the idea to apply more sensitive screening options within the standard histo-morphological review process of pathologists.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S2. Validation and application of PCR to detect H. pylori on gastric biopsies. Representative results of the multiplex real-time PCR performed with the RIDA GENE® Helicobacter pylori assay (r-biopharma, Darmstadt, Germany). (A) Amplification of the internal control DNA. (B) Amplification of the specific sequence for H. pylori (16SrRNA). Positive control is shown in red and the non-template control in black for each channel. (C) Amplification of the specific sequence for the detection of the Clarithromycin resistance (23S rRNA). Positive control is shown in red and the non-template control in black for each channel. (D) Serial dilution (1:2) of the positive control (5000 copies/μl starting concentration). The RIDA GENE® Helicobacter pylori assay (r-biopharma, Darmstadt, Germany) can detect down to 9.8 copies/μl in an unknown sample. Shown are the fluorescence signals of the H. pylori channel (FAM/RFU). RFU: relative fluorescence units.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Visualization of the decisions of the applied CNN and its false detections. (A–D) Synthetic images that maximize the H. pylori category score and the non- H. pylori category score. (E–H). Visualization results that confused the network, and which falsely lead to H. pylori detection (I). For visualization of the features the network searches for, we used the approach of Simonyan et al. [19]. A noise image is inserted to the network, a specific pixel and category in the network output is set as the target, and several iterations of gradient ascent are run in order to modify the input image pixels to receive a high value in the target pixel. Using this we created examples of input images, that caused a high activation at the target pixel for each of the categories. For creating smooth image visualizations, we followed the example of Smilkov et al. and used regularization by rotations, reflections, and normalization of the gradients. We observed that images maximizing the H. pylori category contained multiple H. pylori looking like bodies, and images maximizing the H. pylori category did not have these features.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CNN

Convolutional neural network

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- WSI

Whole slide image

- AI

Artificial intelligence

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

Authors’ contributions

SK, JG, RB: Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript; AQ: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript; KWN, MP critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, MI: critical revision of the manuscript, technical or material support; SMB technical or material support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported with a fellowship from the Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung granted to SK (2015_Kolleg.19).

Availability of data and materials

All data (whole slide images) used in the manuscript are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. DeePathology Ltd. will consider making the manuscript code available per request for academic institutions for non-clinical, academic research purposes.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ethical review board of the University Hospital Cologne. The study was performed in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JG is Co-Founder of DeePathology Ltd., DeePathology Ltd. filed a patent on H. pylori detection on whole slide images (JG was not involved in the process of validation of the algorithm). All other authors declare to conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sebastian Klein and Jacob Gildenblat have contributed equally to this works

Contributor Information

Sebastian Klein, Email: Sebastian.Klein@uk-koeln.de.

Reinhard Büttner, Email: Reinhard.Buettner@uk-koeln.de.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12876-020-01494-7.

References

- 1.Murdoch TB, Detsky AS. The inevitable application of big data to health care. JAMA. 2013;309(13):1351. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solnick JV, O’Rrourke J, Lee A, et al. An uncultured gastric spiral organism is a newly identified Helicobacter in humans. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(2):379–385. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss SM, Kulikowski CA, Amarel S, et al. A model-based method for computer-aided medical decision-making. Artif Intell. 1978;11(1–2):145–172. doi: 10.1016/0004-3702(78)90015-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IARC Working Group Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(16):1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F, et al. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1991;302(6788):1302–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(16):1132–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt R, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication for the prevention of gastric neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD005583. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005583.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, et al. The effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(5):1037–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu C, Kuo KN, Wu M, et al. Early Helicobacter pylori eradication decreases risk of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1641–1648.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Pauligk C, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a ra. Lancet (Lond Engl) 2019;393(10184):1948–1957. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs CS, Mayer RJ. Gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(1):32–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chey WD, Wong BCY, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection–the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61(5):646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor A, O’Morain CA, Ford AC. Population screening and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(4):230–240. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature14539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. 2014. https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556

- 19.Simonyan K, Vedaldi A, Zisserman A. Deep inside convolutional networks: visualising image classification models and saliency maps. 2013. https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6034

- 20.Lahiani A, Gildenblat J, Klaman I et al. Generalizing multistain immunohistochemistry tissue segmentation using one-shot color deconvolution deep neural networks. https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.06958

- 21.Smilkov D, Thorat N, Kim B, Viégas F, Wattenberg M. SmoothGrad: removing noise by adding noise. 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03825

- 22.Martin DR, Hanson JA, Gullapalli RR, Schultz FA, Sethi A, Clark DP. A deep learning convolutional neural network can recognize common patterns of injury in gastric pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019 doi: 10.5858/arpa.2019-0004-oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang CR, Sheu BS, Chung PC, Yang HB. Computerized diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection and associated gastric inflammation from endoscopic images by refined feature selection using a neural network. Endoscopy. 2004;36(7):601–608. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shichijo S, Nomura S, Aoyama K, Nishikawa Y, Miura M, Shinagawa T, Hirotoshi T, Tetsuya T, Soichiro I, Keigo I, Tada T. Application of convolutional neural networks in the diagnosis of helicobacter pylori infection based on endoscopic images. EBioMedicine. 2017;25:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh T, Kawahira H, Nakashima H, Yata N. Deep learning analyzes Helicobacter pylori infection by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy images. Endosc Int Open. 2018;06(02):E139–E144. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-120830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang KK, Ramnarayanan K, Zhu F, et al. Genomic and epigenomic profiling of high-risk intestinal metaplasia reveals molecular determinants of progression to gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(1):137–150.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S2. Validation and application of PCR to detect H. pylori on gastric biopsies. Representative results of the multiplex real-time PCR performed with the RIDA GENE® Helicobacter pylori assay (r-biopharma, Darmstadt, Germany). (A) Amplification of the internal control DNA. (B) Amplification of the specific sequence for H. pylori (16SrRNA). Positive control is shown in red and the non-template control in black for each channel. (C) Amplification of the specific sequence for the detection of the Clarithromycin resistance (23S rRNA). Positive control is shown in red and the non-template control in black for each channel. (D) Serial dilution (1:2) of the positive control (5000 copies/μl starting concentration). The RIDA GENE® Helicobacter pylori assay (r-biopharma, Darmstadt, Germany) can detect down to 9.8 copies/μl in an unknown sample. Shown are the fluorescence signals of the H. pylori channel (FAM/RFU). RFU: relative fluorescence units.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Visualization of the decisions of the applied CNN and its false detections. (A–D) Synthetic images that maximize the H. pylori category score and the non- H. pylori category score. (E–H). Visualization results that confused the network, and which falsely lead to H. pylori detection (I). For visualization of the features the network searches for, we used the approach of Simonyan et al. [19]. A noise image is inserted to the network, a specific pixel and category in the network output is set as the target, and several iterations of gradient ascent are run in order to modify the input image pixels to receive a high value in the target pixel. Using this we created examples of input images, that caused a high activation at the target pixel for each of the categories. For creating smooth image visualizations, we followed the example of Smilkov et al. and used regularization by rotations, reflections, and normalization of the gradients. We observed that images maximizing the H. pylori category contained multiple H. pylori looking like bodies, and images maximizing the H. pylori category did not have these features.

Data Availability Statement

All data (whole slide images) used in the manuscript are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. DeePathology Ltd. will consider making the manuscript code available per request for academic institutions for non-clinical, academic research purposes.