Abstract

When faced with changing contingencies, animals can use memory to flexibly guide actions, engaging both frontal and temporal lobe brain structures. Damage to the hippocampus (HPC) impairs episodic memory, and damage to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) impairs cognitive flexibility, but the circuit mechanisms by which these areas support flexible memory processing remain unclear. The present study investigated these mechanisms by temporarily inactivating the medial PFC (mPFC), the dorsal HPC (dHPC), and the ventral HPC (vHPC), individually and in combination, as rats learned spatial discriminations and reversals in a plus maze. Bilateral inactivation of either the dHPC or vHPC profoundly impaired spatial learning and memory, whereas bilateral mPFC inactivation primarily impaired reversal versus discrimination learning. Inactivation of unilateral mPFC together with the contralateral dHPC or vHPC impaired spatial discrimination and reversal learning, whereas ipsilateral inactivation did not. Flexible spatial learning thus depends on both the dHPC and vHPC and their functional interactions with the mPFC.

Keywords: executive function, hippocampus, learning, memory, prefrontal cortex, spatial memory, temporal lobe

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Memory helps us adapt to changing circumstances. For example, remembering yesterday’s unexpected construction delays along the usual route to work could prompt us to take a different route today. Flexible memory-guided behavior depends on interactions between frontal and temporal brain structures. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is central to behavioral and cognitive flexibility, while the hippocampus (HPC) is central to episodic and spatial memory. Neuropsychological (Churchwell & Kesner, 2011; Floresco, Seamans, & Phillips, 1997; Goto & Grace, 2008; Maharjan, Dai, Glantz, & Jadhav, 2018; Spellman et al., 2015; Wang & Cai, 2006, 2008) and physiological studies (Guise & Shapiro, 2017; Jadhav, Rothschild, Roumis, & Frank, 2016; Jones & Wilson, 2005) show that the medial PFC (mPFC) and HPC interact when rodents use recent memory to flexibly guide spatial choices. However, the mPFC-HPC circuitry that supports flexible spatial memory remains unclear.

Neuropsychological, recording, and anatomical studies show that function and connectivity vary along the longitudinal axis of the HPC (Bannerman et al., 2004; Fanselow & Dong, 2010; Strange, Witter, Lein, & Moser, 2014). Whereas lesions of the dorsal HPC (dHPC) impaired performance on spatial memory tasks, similar lesions of the ventral HPC (vHPC) had little to no effect on spatial memory (Bannerman et al., 1999, 2002; Moser & Moser, 1998; Moser, Moser, Forrest, Andersen, & Morris, 1995; Pothuizen, Zhang, Jongen-Rêlo, Feldon, & Yee, 2004). Consistent with this neuropsychology, place cells in the dHPC signal more precise spatial information than those in the vHPC (Jung, Wiener, & McNaughton, 1994; Kjelstrup et al., 2008). In contrast, vHPC lesions reduced behavioral measures of anxiety, whereas dHPC lesions reduced anxiety less consistently or not at all (Bannerman et al., 2002; McHugh, Deacon, Rawlins, & Bannerman, 2004). These results suggest that the dHPC and vHPC may have different functions, and that spatial memory processing depends on the dHPC but not the vHPC.

However, the vHPC provides the main hippocampal input to the PFC, suggesting that spatial memory should depend on the vHPC when hippocampal-prefrontal communication is required. Ventral CA1 and subiculum axons form a dense, monosynaptic, primarily ipsilateral input to mPFC (Hoover & Vertes, 2007; Jay, Glowinski, & Thierry, 1989; Jay & Witter, 1991; Swanson, 1981), while dorsal CA1 input to mPFC is sparse (Hoover & Vertes, 2007; Ye, Kapeller-Libermann, Travaglia, Inda, & Alberini, 2017). Indeed, inactivating ventral CA1 terminals within mPFC impaired spatial working memory in mice (Spellman et al., 2015), suggesting that flexible processing of spatial information requires vHPC-mPFC communication.

Flexible spatial memory processing may also depend on signaling from the mPFC to the HPC. mPFC efferents connect to both dorsal and ventral CA1 via disynaptic connections with neurons in the reuniens and rhomboid nuclei of the thalamus (Cassel et al., 2013; Prasad & Chudasama, 2013; Vertes, Hoover, Szigeti-Buck, & Leranth, 2007) and via parahippocampal cortices (Apergis-Schoute, Pinto, & Paré, 2006). These pathways may allow mPFC signals to guide hippocampal spatial computations. Indeed, inactivation of bilateral mPFC or the nucleus reuniens degraded prospective spatial coding in dorsal CA1 during flexible spatial memory tasks in rats (Guise & Shapiro, 2017; Ito, Zhang, Witter, Moser, & Moser, 2015).

These results suggest that flexible spatial memory processing can depend on both the dHPC and vHPC and their interactions with the mPFC. To test this prediction, we temporarily inactivated the mPFC, dHPC, and vHPC in various combinations before rats learned spatial discriminations and reversals in a plus maze. Previous work has demonstrated that both spatial discriminations and reversals in a plus maze are impaired by complete bilateral HPC lesions (Ferbinteanu, Shirvalkar, & Shapiro, 2011), whereas only reversals are impaired by bilateral mPFC inactivation (Guise & Shapiro, 2017). This study aimed to check and extend these findings by testing the separate contributions to learning of the dHPC, vHPC, and mPFC, as well as of the interactions between the mPFC and the dHPC or vHPC. Separate contributions of the mPFC, dHPC, and vHPC to learning were tested by inactivating these structures bilaterally. Contributions of interactions between the mPFC and hippocampal subregions were tested by inactivating unilateral mPFC together with the contralateral dHPC or vHPC (“crossed inactivation”). Because the majority of monosynaptic vHPC-mPFC (Hoover & Vertes, 2007; Jay et al., 1989) and disynaptic mPFC-dHPC and mPFC-vHPC (Hoover & Vertes, 2012; Vertes, 2002; Vertes et al., 2007) connections are ipsilateral, crossed inactivation of the mPFC and a hippocampal subregion should disrupt their interactions in both hemispheres and impair behavior that depends on those interactions (e.g., Floresco et al., 1997). In contrast, inactivating these structures ipsilaterally should leave their interactions intact in the opposite hemisphere, impairing interaction-dependent behavior less or not at all. We found that bilateral dHPC or vHPC inactivation profoundly impaired spatial learning and memory, while bilateral mPFC inactivation impaired reversal more than discrimination learning. Crossed inactivation of mPFC and either dHPC or vHPC impaired discrimination and reversal learning, while ipsilateral inactivation did not affect learning. These results suggest that flexible spatial learning depends on both the dHPC and vHPC and their functional interactions with the mPFC.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Experimental design

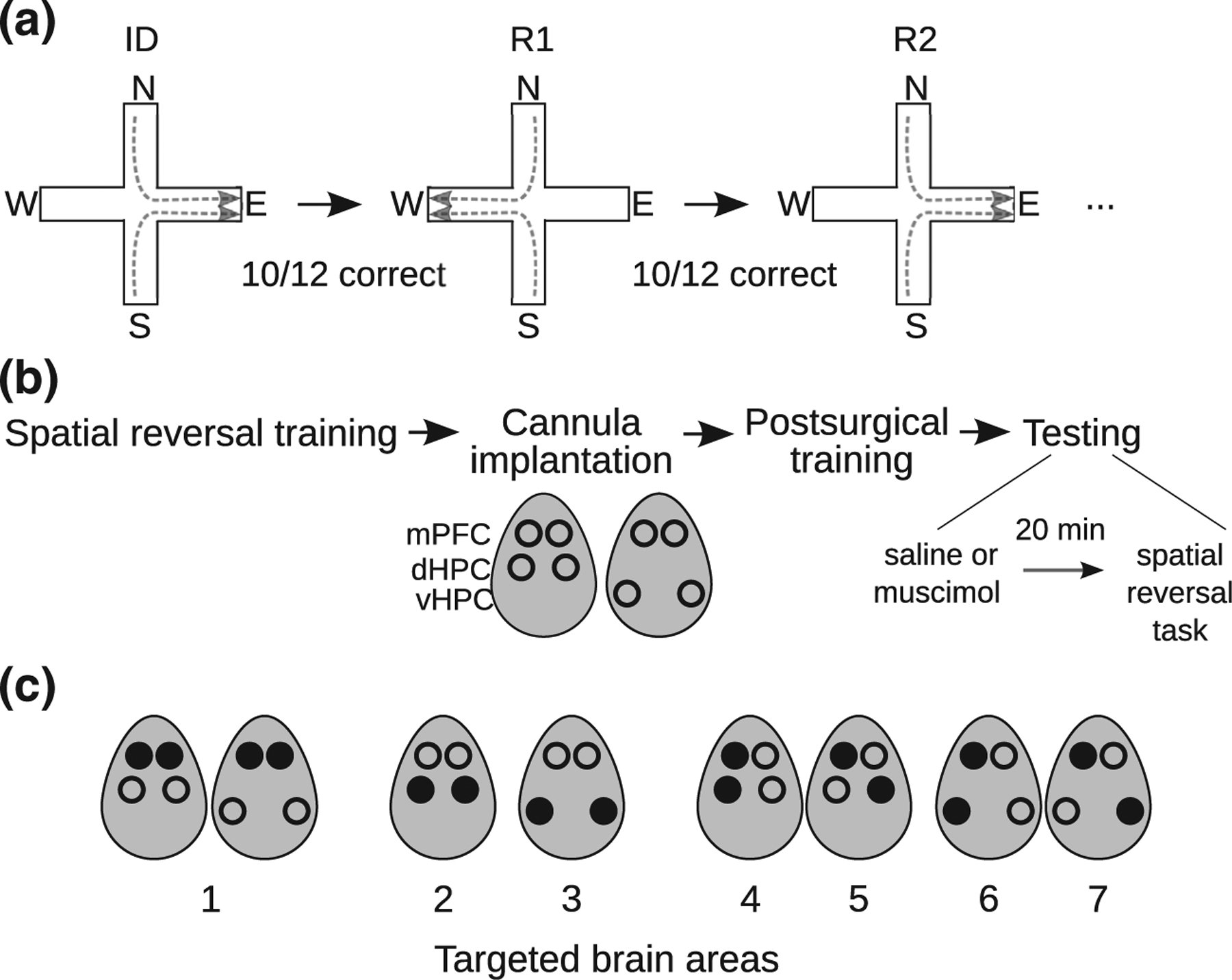

Flexible spatial learning was tested in 25 rats using a spatial win-stay task with reversals in a plus maze (Ferbinteanu & Shapiro, 2003). In this task, rats learn an initial spatial discrimination (ID) followed by a series of spatial reversals (R1, R2, etc.). Each rat was handled and acclimated to the maze, trained in the task, implanted surgically with two pairs of bilateral cannulae, one pair targeting the mPFC and the other pair targeting either the dHPC or vHPC, and retrained after recovery from surgery. The contributions of the mPFC, dHPC, and vHPC to spatial discrimination and reversal learning were examined by temporarily inactivating different combinations of these areas via muscimol microinjections prior to task performance (Figure 1). Each experiment testing a combination of brain areas was performed in four daily sessions. The four consecutive sessions interleaved saline and muscimol injections in an ABBA order (saline, muscimol, muscimol, saline). Most rats were tested in several experiments. To verify that criterion performance was maintained after completing each experiment, rats were given several rest days and then tested without injections before starting the next experiment.

FIGURE 1.

Experimental design. (a) Spatial discrimination and reversal task. In each session, rats learned an initial spatial discrimination (ID; e.g., “go East”) followed by a series of spatial reversals (R1, R2, etc.; e.g., “go West”, “go East”, etc.) in a plus maze. (b) Rats were trained on the spatial reversal task and then implanted with cannulae targeting bilateral mPFC and either bilateral dorsal HPC or bilateral ventral HPC. Ovals show dorsal view of rat head, with cannulae indicated by circles. The effects of inactivating targeted brain areas on initial spatial discrimination and reversal learning were then tested. Targeted brain areas were injected with saline or muscimol 20 min before spatial reversal task performance. C, Targeted brain areas. Filled circles indicate injection sites. Bilateral (1) mPFC, (2) dHPC or (3) vHPC; (4) ipsilateral or (5) crossed mPFC-dHPC; (6) ipsilateral or (7) crossed mPFC-vHPC

2.2 |. Animals

Long-Evans rats (n = 25, male, ~ 2 months old, Charles River Laboratories) acclimated to a reverse light-dark cycle colony for ~2 weeks with free access to food and water. Rats were then food-restricted and weighed daily to maintain 85–90% of ad lib body weight, adjusted for normal growth. Rats were handled for 4 days prior to maze acclimation. All training and testing occurred during the dark phase. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and complied with national guidelines on the care and use of laboratory animals (National Research Council, 2010).

2.3 |. Apparatus

Two dimly lit rooms with distal visual stimuli (e.g., posters) on the walls each contained a plus maze, elevated 85 cm above the floor, with four open arms and edges 2 cm high. One maze was 122 cm across with arms 10 cm wide; the other maze was 135 cm across with arms 6 cm wide. The four arms of each maze were named as North, East, South, and West. The North and South arms were designated as start arms, the East and West arms as goal arms, and the maze center as the choice point. The distal end of each goal arm had a recessed drill hole (1 cm diameter, 1 cm deep) containing a food cup, which was not visible from other locations. Inaccessible chocolate sprinkles taped beneath both goal arms minimized the influence of odor cues on behavior. An elevated waiting platform (40 cm L × 30 cm W × 100 cm H) with raised edges (6 cm) was located next to each maze.

2.4 |. Maze acclimation and training

For each rat, all maze acclimation, task training, and testing (described below) was confined to one of the two mazes. Rats were given two or three maze acclimation sessions before task training. In these sessions, individual rats were placed on one of the two start arms and allowed to explore the maze. Chocolate sprinkles were available in the food cups of both goal arms to encourage exploration. After the maze acclimation sessions, rats were trained in the task described below. Each rat was given five daily training sessions per week until its session-wide choice accuracy exceeded 80% in two out of three consecutive sessions, then was surgically implanted with cannulae (see below). After recovery, rats were given five daily postsurgical training sessions per week until session-wide accuracy again exceeded 80% in two out of three consecutive sessions.

2.5 |. Spatial discrimination and reversal task

At the beginning of a task session, a rat was brought into the behavioral room and placed on the waiting platform. One of the goal arms was pseudorandomly selected as the initially rewarded arm by a computer program (probability (East) = probability (West) = 0.5, where the same goal arm could not be selected for >3 consecutive sessions), defining the reward contingency of the initial spatial discrimination (e.g., “go East”). At the beginning of each trial of the spatial discrimination block, the experimenter placed chocolate sprinkles in the cup of the rewarded goal arm. The experimenter also faux-baited the other goal arm, without placing sprinkles there, to avoid cuing the rat to the rewarded arm. The rat was then transferred from the waiting platform to the distal end of a pseudorandomly selected start arm (selection by computer program; North and South arms selected with equal probability, where the same start arm could not be selected for >3 consecutive trials). The rat then approached and crossed the choice point, making a choice when it placed all four paws on another arm. If the rat chose the rewarded arm, it was allowed to eat the food and was then returned to the waiting platform. If the rat chose an unrewarded arm in the first trial of the reward contingency or after five consecutive errors, it was allowed to self-correct, that is, freely enter arms until it found and ate the food, and was then returned to the waiting platform. In all other cases, the experimenter returned the rat to the waiting platform after it chose an unrewarded arm. The rat remained on the waiting platform for a 10 s intertrial interval before starting the next trial. The rat reached a spatial discrimination learning criterion if it chose the rewarded arm in 10/12 consecutive trials. Reaching this criterion triggered a contingency reversal (e.g., “go East” → “go West”), such that a reversal learning block, in which the other goal arm was rewarded, started on the next trial. Procedures during reversal learning were the same as described above for discrimination learning, with subsequent goal arm reversals occurring according to the 10/12 learning criterion. The session ended when the rat performed 64 trials or an hour had elapsed. Excluding the first trials of new blocks, choices were scored as correct when rats entered rewarded arms and as incorrect/errors when they entered unrewarded ones.

2.6 |. Surgery

Each rat was implanted bilaterally with two pairs of injection cannula, one pair targeting the mPFC and the other pair targeting either the dorsal or ventral hippocampus. The rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (VetEquip, Inc.) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments). Anesthesia was maintained with 1–4% isoflurane. Core body temperature was maintained with a rectal thermometer and a heating pad (World Precision Instruments), and rats’ eyes were coated with ophthalmic ointment (Puralube, Dechra Veterinary Products). Rats received physiological saline (1 ml, s.c.) and either ketoprofen (5 mg/kg, s.c., Sigma-Aldrich) or Loxicom (4 mg/kg, s.c., Norbrook Laboratories) for analgesia. After rats reached surgical anesthesia, the scalp was shaved, scrubbed with Betadine, and anesthetized with Xylocaine (0.5 ml, s.c., APP Pharmaceuticals), and a midsagittal incision was made. The skull was leveled so that bregma and lambda were in the same horizontal plane and two pairs of bilateral holes were drilled, one above either dHPC (n = 13) or vHPC (n = 12) and one above mPFC. Bilateral guide cannulae (26 gauge, Plastics One) were implanted targeting mPFC (infralimbic/prelimbic areas; from bregma: AP +3.0 mm, ML ±1.8 mm; from dura: DV −2.0 mm at a 14° medial angle) and either dorsal CA1 (AP −3.6 mm, ML ±2.9 mm, DV −1.8 mm at a 14° medial angle) or ventral CA1 (AP −5.4 mm, ML ±5.3 mm, DV −5.0 mm). Coordinates were obtained from Paxinos and Watson (2007). Guide cannulae were fixed to the skull with dental acrylic (Coltene Whaledent) and stainless steel bone screws. Dummy cannulae were inserted into the guides to keep them patent and protruded slightly from the guide tips (mPFC: 1.5 mm; dHPC and vHPC: 1 mm) to clear space for injection cannulae. Following surgery, rats were placed in clean, warm home cages, observed until mobile, and monitored for postoperative pain or infections for at least 7 days before training resumed. Rats gained weight normally, displayed no signs of inflammation or infection at the surgical site, and behaved normally after recovery.

2.7 |. Targeted inactivation and behavioral testing

After completing postsurgical training, rats were tested on the spatial discrimination and reversal task. Targeted microinjections of saline or the GABAA agonist muscimol were given before each testing session. Dummy cannulae at target sites were replaced with 33 gauge injection cannulae (Plastics One) that extended either 1.5 mm (mPFC) or 1.0 mm (d/vHPC) past the tips of the guide cannulae. The intended coordinates for the injection cannula tips relative to bregma (AP, ML) and dura (DV) were: mPFC: AP +3.0 mm, ML ±0.95 mm, DV −3.40 mm; dHPC: AP −3.6 mm, ML ±2.22 mm, DV −2.72 mm; vHPC: AP −5.4 mm, ML ±5.3 mm, DV −6.0 mm (Paxinos & Watson, 2007). The injection cannulae were connected, via clear Tygon tubing, to 2 μl Hamilton syringes mounted onto a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) and delivered 0.5 μl of saline (0.9%) or muscimol (Sigma; mPFC: 0.1 mg/ml, d/vHPC: 1 mg/ml) at a rate of 0.25 μl/min. Microinjection volumes were verified by measuring the distance that a small air bubble loaded into the tubing traveled. Injection cannulae were kept in place for 1 min after injection to promote diffusion, and then the dummy cannulae were reinserted and the rat was returned to its home cage. Testing on the spatial discrimination and reversal task began 20 min afterward.

Microinjections targeted seven different combinations of brain areas: (a) bilateral mPFC (n = 19), (b) bilateral dHPC (n = 9), (c) bilateral vHPC (n = 11), (d) ipsilateral mPFC-dHPC (n = 11), (e) crossed mPFC-dHPC (n = 11), (f) ipsilateral mPFC-vHPC (n = 8), and (g) crossed mPFC-vHPC (n = 8). Ipsilateral injections targeted unilateral mPFC together with the ipsilateral dHPC or vHPC, while crossed injections targeted unilateral mPFC together with the contralateral dHPC or vHPC. Because anatomical connections between the mPFC and both the dHPC and vHPC are mainly ipsilateral, crossed inactivation of the mPFC and either hippocampal subregion should disable interactions between the inactivated structures in both hemispheres, while ipsilateral inactivation should preserve interactions in the opposite hemisphere. The behavioral effects of each set of brain injections were tested in separate experiments that each included four consecutive daily sessions, with saline and muscimol injections alternating in an ABBA order (saline, muscimol, muscimol, saline). Most rats were tested in several experiments. After completing an experiment rats were given several rest days. To verify that baseline performance remained at asymptotic levels after the rest days (session accuracy ≥80%), the rats were given a behavioral testing session without injections before beginning the next experiment.

2.8 |. Data analysis

Statistics were performed using SPSS and MATLAB (MathWorks). Tests were two-sided and used an alpha level of 0.05. Analyses for each combination of brain areas focused on performance in the first saline and muscimol sessions of testing, avoiding potential carryover effects of muscimol on subsequent sessions. Analyses focused on the initial spatial discrimination (ID) and first reversal (R1), as many rats did not reach learning criteria to perform additional blocks after muscimol injections.

2.8.1 |. Learning

Discrimination and reversal learning were measured in several ways. For ID and R1, choice accuracy (% trials correct) was calculated, and numbers of trials performed and errors committed were counted. Number of trials performed, versus trials to criterion, was used to measure learning because rats given muscimol injections did not always reach learning criteria (Table 1). Repeated measures ANOVA, with these measures as dependent variables, was used to analyze factors affecting learning. Learning was analyzed separately for bilateral mPFC injections (learning block × drug), bilateral dHPC or vHPC injections (block × drug × HPC subregion), and tandem injections of the mPFC and dHPC or vHPC (hemisphere [ipsilateral versus crossed] × block × drug × HPC subregion). All independent variables were within-subjects except for HPC subregion, which was between-subjects. For tandem injections, supplementary repeated measures ANOVA (block × drug) were performed to separately analyze learning for ipsilateral mPFC-dHPC injections, ipsilateral mPFC-vHPC injections, crossed mPFC-dHPC injections, and crossed mPFC-vHPC injections. Significant ANOVA results were followed up with post hoc paired t-tests or F-tests.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of rats that reached initial discrimination (ID) and first reversal (R1) learning criteria after saline and muscimol injections into different target areas

| Injection sites | Saline | Muscimol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | R1 | ID | R1 | |

| Bilateral mPFC (n = 19) | 19 (100%) | 19 (100%) | 19 (100%) | 16 (84.2%) |

| Bilateral dHPC (n = 9) | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Bilateral vHPC (n = 11) | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 7 (63.6%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| Ipsilateral mPFC-dHPC (n = 11) | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) |

| Crossed mPFC-dHPC (n = 11) | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 10 (90.9%) |

| Ipsilateral mPFC-vHPC (n = 8) | 8 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 7 (87.5%) |

| Crossed mPFC-vHPC (n = 8) | 8 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 7 (87.5%) |

Previous studies have reported that mPFC dysfunction increases proactive interference on memory and impairs learning following rule shifts (Guise & Shapiro, 2017; Peters, David, Marcus, & Smith, 2013; Peters & Smith, 2013). We therefore assessed the effects of mPFC inactivation on early versus late stages of discrimination and reversal learning. Early stages of ID and R1 spanned the trials required for rats to make four correct responses out of six trials, and late stages spanned the subsequent trials. Effects of inactivation on early versus late learning were assessed separately in ID and R1 using repeated measures ANOVA (stage × drug). The R1 analysis excluded two rats that did not make it to late-stage R1 after bilateral mPFC inactivation.

2.8.2 |. Goal and start arm errors

Throughout training and testing, reward alternated between the East and West goal arms, while the North and South start arms were never rewarded. Incorrect entries into the North or South arm (“start arm errors”) could hence reflect failure of long-term memory, while incorrect entries into the East or West arm (“goal arm errors”) could reflect failure of recent memory. Specific arm entries were recorded during training and testing for 18 rats, allowing analysis of goal and start arm errors (choices of the other rats were scored as correct/incorrect without specific arm entries recorded). Goal and start arm errors were analyzed separately using repeated measures ANOVA with the frequency of the error type as the dependent variable. Errors were analyzed separately for bilateral mPFC injections (learning block × drug), bilateral dHPC or vHPC injections (drug × HPC subregion; error frequencies pooled across ID and R1 due to low numbers of rats that progressed to R1 after inactivation, see Table 1), and tandem injections of the mPFC and dHPC or vHPC (hemisphere × block × drug × HPC subregion).

2.8.3 |. Perseveration

Previous studies have reported that mPFC lesions or inactivation caused rats to perseverate on innate (Dias & Aggleton, 2000) or previously learned (Ragozzino, Detrick, & Kesner, 1999; Ragozzino, Kim, Hassert, Minniti, & Kiang, 2003) responses after shifts in reward contingency. Here, perseveration on the previously rewarded response during R1 was measured by counting the number of goal arm errors captured by a moving 3-trial window that began at the start of the block and advanced trial-by-trial until it contained <2 goal arm errors (method inspired by Hunt & Aggleton, 1998; Ragozzino et al., 1999). The effect of drug on perseveration was analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

2.8.4 |. Egocentric strategies

If spatial memory were impaired, rats might use nonspatial response strategies in the maze task. During testing, we noticed that muscimol injections caused some rats to repeat the same egocentric body turn over multiple trials, despite such a strategy only leading to reward on ~50% of trials. We sought to quantify the tendency for rats to repeat body turns in the various experimental conditions. For ID and R1 of a testing session, body turns (right versus left) in error trials were compared to the body turn of the previous trial, generating counts of repeated and unrepeated body turn errors. A binomial test then calculated the probability of the observed degree of body-turn repetition under the null hypothesis of no body-turn tendency (i.e., # repeated turns = # unrepeated turns), quantifying an individual rat’s tendency to repeat body turns in the given experimental condition. To quantify body-turn tendency on a group level, rats’ individual p-values in each experimental condition (defined by targeted brain areas, treatment, and learning block) were aggregated into group-level p-values using Fisher’s method (Elston, 1991). Given the large number (28) of different groups, we corrected our interpretation of these group-level p-values for multiple hypothesis testing by using the Bonferroni-Holm step-down procedure with familywise error rate set to 0.05, and report groups with significant p-values after correction.

2.9 |. Histology

Rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were postfixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, cryoprotected in 15% sucrose followed by 30% sucrose, then snap-frozen in dry ice. Sections (25–50 μm thick) were mounted, stained with formal-thionin and inspected microscopically to verify cannula tip placement.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Histology

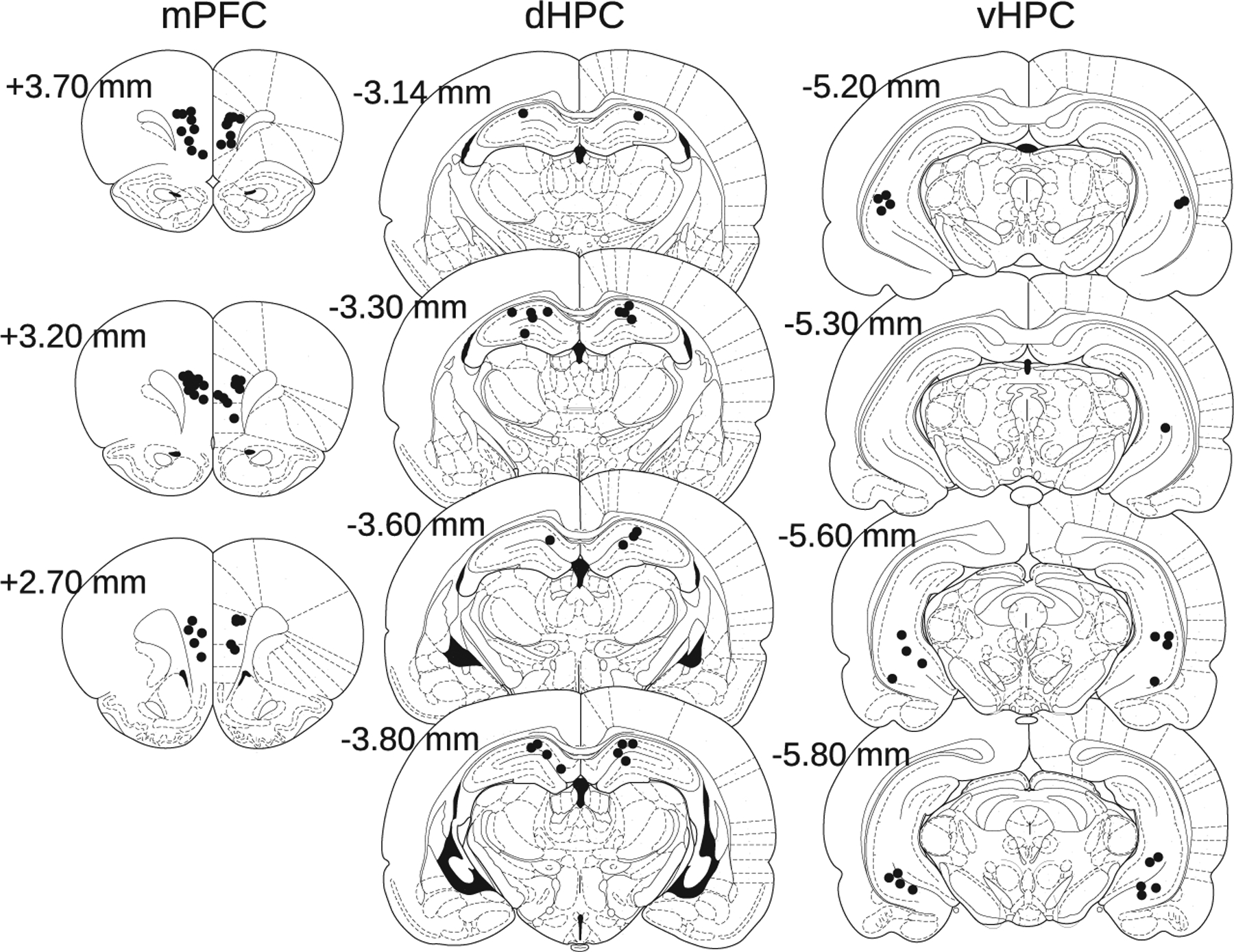

The tips of injection cannulae were located in targeted brain areas (Figure 2). Most mPFC cannulae were located in the prelimbic cortex, with a minority near the prelimbic-infralimbic border or in the infralimbic cortex. Most dHPC cannulae were located in dorsal CA1, with a minority in or near the hippocampal fissure or in dorsal CA3 or dentate gyrus. Most vHPC cannulae were located near the ventral CA1 cell layer, with some near ventral CA2, CA3, or dentate gyrus.

FIGURE 2.

Cannula locations. Black circles indicate histologically verified cannula tip locations for injections targeting mPFC (left), dHPC (middle), and vHPC (right), shown on coronal plates from Paxinos and Watson (2007). AP coordinates relative to bregma are shown

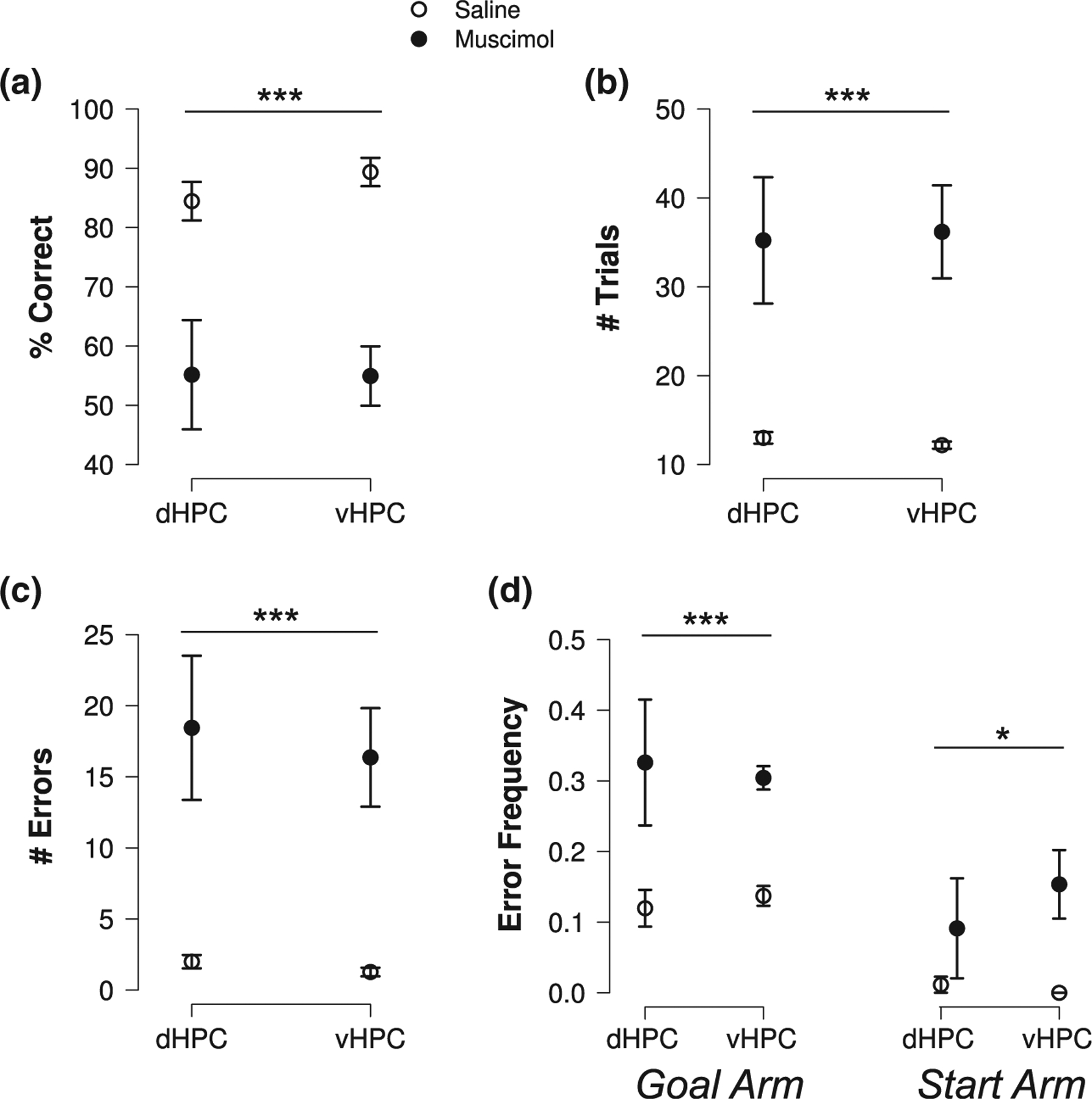

3.2 |. Bilateral inactivation of the dHPC or vHPC impaired spatial learning

Bilateral inactivation of either the dorsal (n = 9) or ventral (n = 11) HPC severely impaired both initial spatial discrimination and reversal learning. Whereas all rats completed ID and R1 (i.e., sequentially reached ID and R1 learning criteria) after saline microinjections into the dHPC or vHPC, muscimol microinjections into these areas prevented multiple rats from reaching ID or R1 learning criteria (Table 1). Because muscimol prevented many rats from being tested on R1, we first analyzed ID learning by itself. Inactivation of the dHPC or vHPC severely impaired ID learning (Figure 3a–c), reducing choice accuracy (drug: F(1,18) = 41.706, p < .001) and increasing numbers of trials performed (F(1,18) = 27.800, p < .001) and errors made (F(1,18) = 27.339, p < .001). These ID learning impairments were similar for dHPC and vHPC inactivation (subregion × drug interactions: all F(1,18)’s < 0.3, all p’s > .6). Analysis of performance over the first 10 ID trials revealed that inactivation of either HPC subregion impaired learning in these trials, with a stronger effect of vHPC than dHPC inactivation (mus - sal difference in choice accuracy over first 10 ID trials: vHPC: −44.4 (mean) ± 5.0% (SEM), dHPC: −23.5 ± 7.0%; drug × subregion interaction: F(1,18) = 6.247, p = .022; sal vs. mus post hoc t-tests: dHPC: t(8) = 3.8, p = .001, vHPC: t(10) = 7.9, p < .001).

FIGURE 3.

Bilateral dHPC or vHPC inactivation impaired spatial learning. Inactivating either HPC subregion (a) decreased choice accuracy and (b) increased the number of trials performed and (c) errors during initial discrimination learning. (d) Inactivating either HPC subregion increased both incorrect goal arm and incorrect start arm entries. Goal and start arm error data are pooled across ID and R1. Plots show means ± SEMs. A set of asterisks indicates a significant difference between saline and muscimol (significant ANOVA main effect of drug) over the conditions spanned by the bar. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Both initial discrimination and reversal learning were analyzed in rats that successfully completed ID and hence progressed to R1 testing after dHPC or vHPC inactivation. Among these rats, inactivation of either HPC subregion impaired choice accuracy (drug: F(1,9) = 12.639, p = .006) and increased numbers of trials performed (F(1,9) = 19.541, p = .002) and errors (F(1,9) = 17.679; p = .002) across ID and R1. There was no significant evidence that impairments differed across learning blocks or hippocampal subregions (drug × subregion, drug × block, and drug × subregion × block interactions: all F(1,9)’s < 2.3, all p’s > .15). Overall, the results show that spatial learning depended on both the dHPC and vHPC.

3.3 |. Bilateral dHPC or vHPC inactivation increased entries to never-rewarded arms

Rats were exposed to a consistent spatial reward rule on the plus maze: the North and South start arms were never rewarded. Over training, rats formed and used long-term spatial memory to avoid entering these unrewarded locations. During the last postsurgical training session, they entered incorrect goal arms in 18% of trials versus start arms in only 1% of trials (signed rank = 171, p = 1.9 × 10−4). Incorrect start arm entries could reflect failure of long-term spatial memory, for example, forgetting the map of the environment or the stable spatial rule that the North and South arm never contain food. In contrast, incorrect goal arm entries could reflect failure of recent memory, for example, forgetting whether the chosen goal arm was rewarded in the previous trial. If dHPC or vHPC function is needed for recent, but not long-term, spatial memory, then inactivation of that hippocampal subregion should selectively increase goal arm errors. If dHPC or vHPC function is required for long-term spatial memory, then inactivation should also increase start arm errors. Bilateral dHPC and vHPC inactivation increased goal arm errors (Figure 3d; drug: F(1,13) = 30.592, p < .001). Bilateral inactivation of HPC subregions also increased start arm errors (F(1,13) = 6.478, p = .024), suggesting that the dHPC and vHPC con to long-term spatial memory.

3.4 |. Bilateral mPFC inactivation impaired reversal more than discrimination learning and increased perseveration

Bilateral mPFC inactivation (n = 19) impaired both initial and reversal learning, but the effect on reversal learning was stronger (Figure 4a–c). More so in R1 than ID, mPFC inactivation reduced choice accuracy (block × drug: F(1,18) = 9.537, p = .006; sal vs. mus post hoc t-tests: ID: t(18) = 3.6, p = .002; R1: t(18) = 7.6, p < .001) and increased numbers of trials performed (drug: F(1,18) = 39.000, p < .001; block × drug: F(1,18) = 3.621, p = .073) and errors (block × drug: F(1,18) = 10.268, p = .005; sal vs. mus post hoc t-tests: ID: t(18) = 4.5, p < .001; R1: t(18) = 5.0, p < .001). This increase in errors was due to an increase in the frequency of goal arm errors (Figure 4d; drug: F(1,13) = 73.941, p < .001), with start arm error frequency unaffected by mPFC inactivation (sal vs. mus: F(1,13) = 0.697, p = .419), suggesting that inactivation impaired recent but not long-term memory processing.

FIGURE 4.

Bilateral mPFC inactivation impaired spatial reversal more than initial discrimination learning and selectively increased goal arm errors. More so during the first reversal than the initial discrimination, muscimol (a) decreased choice accuracy and (b) increased number of trials performed and (c) errors. (d) Muscimol increased incorrect goal arm entries, but had no effect on incorrect start arm entries. Plots show means ± SEMs. A set of asterisks indicates a significant difference between saline and muscimol (significant post hoc t-tests (a and c) or ANOVA main effect of drug (b and d)) over the conditions spanned by the bar. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Learning was impaired most strongly in the trials following the reversal, with mPFC inactivation decreasing choice accuracy in the early stage of R1 more than in the late stage (stage × drug: F(1,16) = 8.918, p = .009; post hoc t-tests: early R1: t(16) = 6.1, p < .001; late R1: t(16) = 3.1, p = .007). In contrast, mPFC inactivation caused a consistent decrease in choice accuracy throughout ID (stage × drug: F(1,18) = 0.462, p = .505; drug: F(1,18) = 15.744, p = .001). Previous studies have reported that mPFC inactivation increased perseveration on old responses after rule shifts (Ragozzino et al., 1999, 2003). Here, impaired learning following the reversal was associated with perseveration on the initially rewarded choice, with mPFC inactivation increasing perseverative errors during R1 (sal: mean = 0.4, median = 0; mus: mean = 2.1, median = 2; signed rank = 47, p = .0488). Overall, these results suggest that the mPFC contributes to flexible memory processing when contingencies change.

3.5 |. Crossed, but not ipsilateral, inactivation of the mPFC and either the dHPC or vHPC impaired learning

Bilateral dHPC, vHPC, and mPFC inactivation each impaired aspects of spatial learning and memory. To investigate potential contributions to learning of interactions between the mPFC and either the dHPC or vHPC, we compared the effects on learning of crossed and ipsilateral mPFC-dHPC (n = 11) and mPFC-vHPC (n = 8) inactivation.

Crossed inactivation of the mPFC and either HPC subregion impaired ID and R1 learning, while ipsilateral inactivation did not (Figure 5a–c). While performance was similar after ipsilateral inactivation and saline microinjections, crossed inactivation reduced choice accuracy (hemisphere × drug: F(1,17) = 10.360, p = .005; post hoc F-tests: ipsilateral: F(1,17) = 0.911, p = .353; crossed: F(1,17) = 38.242, p < .001) and increased numbers of trials performed (hemisphere × drug: F(1,17) = 8.548, p = .009; post hoc F-tests: ipsilateral: F(1,17) = 2.300, p = .148; crossed: F(1,17) = 18.706, p < .001) and errors (hemisphere × drug: F(1,17) = 9.066, p = .008; post hoc F-tests: ipsilateral: F(1,17) = 2.298, p = .148; crossed: F(1,17) = 24.197, p < .001) across ID and R1, as compared to crossed saline microinjections. For ipsilateral mPFC-vHPC inactivation, numerical increases in mean R1 trial and error counts versus saline were observed. These increases were driven by a single outlier rat (# R1 trials = 52, z = 2.3; # R1 errors = 23, z = 2.3) and did not reach significance (trials, sal vs. mus: t(7) = 1.33, p = .225; errors, t(7) = 1.24, p = .255); excluding this outlier eliminated these differences (trials: t(6) = 0.870, p = .418; errors: t(6) = 0.661, p = .533).

FIGURE 5.

Crossed, but not ipsilateral, inactivation of the mPFC and either the dHPC or vHPC impaired spatial learning. Crossed inactivation (a) decreased choice accuracy and (b) increased numbers of trials performed and (c) errors. (d) Crossed, but not ipsilateral, inactivation increased incorrect goal arm entries. A small increase in start arm errors was detected across crossed and ipsilateral inactivation. Plots show means ± SEMs. A set of asterisks indicates a significant difference between saline and muscimol (significant post hoc F-test (a–d left) or ANOVA main effect of drug (d right)) over the conditions spanned by the bar. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Separate analyses focused on each HPC subregion and hemispheric relationship confirmed that crossed, but not ipsilateral, inactivation of the mPFC and either HPC subregion impaired ID and R1 learning (choice accuracy, main effects of drug: ipsilateral mPFC-dHPC: F(1,10) = 0.269, p = .615; crossed mPFC-dHPC: F(1,10) = 13.755, p = .004; ipsilateral mPFC-vHPC: F(1,7) = 0.540, p = .486; crossed mPFC-vHPC: F(1,7) = 35.137, p = .001). Similar to bilateral mPFC inactivation, crossed mPFC-vHPC inactivation caused numerically greater impairments in R1 than ID, but these differences did not reach significance (choice accuracy: block × drug: F(1,7) = 2.720, p = .1431; trials: block × drug: F(1,7) = 3.274, p = .1133; # errors: block × drug: F(1,7) = 4.112, p = .0822). In contrast to ipsilateral inactivation, crossed inactivation increased the frequency of goal arm errors (Figure 5d; hemisphere × drug: F(1,12) = 8.893, p = .011; post hoc F-tests: ipsilateral: F(1,12) = 1.187, p = .297; crossed: F(1,12) = 26.898, p < .001), suggesting that it caused dysfunction of recent memory. A small increase in start arm error frequency was also detected across ipsilateral and crossed inactivation (drug: F(1,12) = 6.637, p = .024), but crossed inactivation did not increase start arm errors more than ipsilateral inactivation (laterality × drug F(1,12) = 2.299, p = .155). Overall, the impairments following crossed but not ipsilateral inactivation of the mPFC and either HPC subregion suggest that spatial learning and memory depended on interactions between the mPFC and both the dHPC and vHPC.

3.6 |. Bilateral HPC and tandem mPFC-HPC inactivation increased egocentric responses

Reward contingencies were defined spatially in this learning task, and the pseudorandom selection of start arms encouraged rats to learn spatial strategies during training. Intriguingly, rats that received muscimol injections sometimes repeated the same egocentric body turn (i.e., left or right turn at the choice point) over long trial sequences, even though a body-turn response strategy would only be rewarded on ~50% of trials. Based on this observation, we sought to quantify the tendency of rats in each experimental condition (defined by targeted brain areas, drug, and learning block) to use a repeating body-turn strategy (see Methods). No evidence for body-turn repetition was found in any saline conditions. Tendencies for body-turn repetition were detected for bilateral dHPC (group p-value, p = 6.98 × 10−8), bilateral vHPC (p = 1.05 × 10−5), and crossed mPFC-dHPC (p = 1.59 × 10−5) inactivation during ID and ipsilateral mPFC-vHPC inactivation during R1 (p = .0014). These results suggest that dysfunction of the HPC or mPFC-HPC circuitry can cause rats to rapidly incorporate nonspatial egocentric response strategies in a spatial task, despite previous task training.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Bilateral inactivation of either the dHPC or vHPC impaired spatial learning in the plus maze, suggesting that both HPC subregions may contribute to spatial learning and memory. Bilateral mPFC inactivation preferentially impaired reversal learning, consistent with its role in supporting behavioral flexibility. Crossed inactivation of the mPFC and either the dHPC or vHPC impaired spatial discrimination and reversal learning, whereas ipsilateral inactivation did not, suggesting that flexible spatial learning and memory may depend on interactions between the mPFC and both HPC subregions.

4.1 |. Bilateral inactivation of either the dHPC or vHPC impaired learning and memory

Bilateral inactivation of either the dHPC or vHPC profoundly impaired spatial learning. HPC dysfunction has long been known to impair spatial learning and memory (O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978) as well as episodic memory across species (Eichenbaum, 2004; Squire, 1992). The present results are consistent with prior studies using the plus maze that reported spatial learning deficits after lesions of the fimbria-fornix (Ferbinteanu & Shapiro, 2003), the HPC proper (Ferbinteanu, 2016; Ferbinteanu et al., 2011), CA3, and the medial entorhinal cortex (O’Reilly, Alarcon, & Ferbinteanu, 2014).

The dHPC and vHPC are connected with distinct cortical and subcortical networks (Cenquizca & Swanson, 2007) and have been proposed to support spatial and emotional processing, respectively (Bannerman et al., 2004; Fanselow & Dong, 2010). Here, inactivating either dHPC or vHPC strongly impaired task performance, demonstrating that each HPC subregion was required for spatial learning and memory. Though spatial memory tasks are typically impaired by dHPC damage, the contributions of the vHPC to spatial learning and memory have been less clear. In the water maze, excitotoxic dHPC, but not vHPC, lesions impaired learning the location of a hidden platform; however lesions of either hippocampal subregion impaired retrieval of a preoperatively learned location (Moser et al., 1995; Moser & Moser, 1998). While these results suggest that the dHPC, but not vHPC, can support new spatial learning in the absence of the other subregion, they also suggest that, in intact rats, spatial memory functions distribute widely in a gradient along the HPC longitudinal axis (Ferbinteanu & McDonald, 2000). This idea dovetails with electrophysiological recordings showing neurons with progressively larger place fields over the longitudinal axis of the HPC (Jung etal., 1994; Kjelstrup et al., 2008). Moreover, with training, vHPC neurons develop place fields that differentiate spatial environments, possibly supporting contextual memory retrieval (Komorowski et al., 2013).

The extensive preoperative training used in the present experiment may have established representations throughout the longitudinal axis, so that memory retrieval was impaired by inactivating either dorsal or ventral HPC circuits. This view may account for the appearance of start arm errors as well as egocentric strategies after bilateral dHPC or vHPC inactivation. Reward was never available in the start arms, and rats learned to avoid choosing these arms over training (making start arm errors in ~1% of trials in the last training session, versus goal arm errors in ~18% of trials), reflecting the formation and use of long-term spatial memory. Yet rats with bilateral dHPC or vHPC inactivation entered these arms in ~10–15% of trials, suggesting that long-term memory retrieval was impaired. Increases in incorrect goal arm entries suggest impairment of learning and recent memory processing as well. Moreover, inactivating either the dHPC or vHPC caused rats to sometimes use egocentric body-turn response strategies, which would only lead to reward on ~50% of trials, despite having learned previously to use spatial response strategies. Disrupting hippocampal function and thereby spatial memory processing can allow the emergence of competing, HPC-independent, egocentric response strategies (Chang & Gold, 2003), which depend on dorsolateral striatal function (Cook & Kesner, 1988; Packard & McGaugh, 1996). Contrary to the idea of a memory-emotion dissociation between the dHPC and vHPC, the present results show that spatial memory processing can occur over a distributed hippocampal network involving both hippocampal subregions. Furthermore, other results show that dHPC can contribute to emotional processing, for example, by regulating fear memory through a projection to the mPFC (Ye et al., 2017). Together, these studies suggest that neither spatial memory nor emotional computations are confined exclusively to the dorsal or ventral HPC.

4.2 |. Bilateral mPFC inactivation impaired spatial reversal more than discrimination learning

Reversal learning measures the ability to shift from a previously learned response to a new one. Bilateral mPFC inactivation impaired reversal learning more than spatial discrimination learning and increased perseveration on the initial response after the reversal, consistent with the view that the mPFC supports cognitive and behavioral flexibility (e.g., Miller & Cohen, 2001). These findings are consistent with prior work using the same task (Guise & Shapiro, 2017) and other tasks that require flexible responses to identical stimuli, for example, delayed nonmatching to place spatial working memory tasks (Churchwell & Kesner, 2011; Spellman et al., 2015). mPFC inactivation increased goal arm errors but not start arm errors, suggesting that the mPFC contributes to the flexible use of recent memory, for example, keeping track of changing rules, but is not necessary for long-term memory representations. By signaling distinct rules, the mPFC may help differentiate prospective coding by HPC neurons and thereby reduce proactive interference (Guise & Shapiro, 2017; Peters and Smith, 2013). Different subregions of the mPFC may perform different functions (e.g., Dias & Aggleton, 2000), and separate inactivation of these subregions could have different effects on learning. This question remains of interest.

4.3 |. Crossed mPFC-HPC inactivation impaired flexible spatial learning

Crossed inactivation of the mPFC and the dHPC or vHPC disrupted interactions between these structures in both hemispheres, while ipsilateral inactivation left interactions intact in the opposite hemisphere (Floresco et al., 1997). Crossed inactivation of the mPFC and either HPC subregion impaired learning, while ipsilateral inactivation did not, strongly suggesting that learning depended on interactions between the mPFC and both HPC subregions. The lack of impairments after ipsilateral inactivation suggests that a single hemisphere’s mPFC-HPC circuitry was sufficient for learning and that the crossed inactivation impairments cannot be explained by mass action (Lashley, 1950).

Crossed inactivation did not recapitulate all of the effects of bilateral inactivation of mPFC or HPC subregions, and the overlaps and differences may help identify the functions performed by each structure separately and by both together. While bilateral inactivation of HPC subregions increased both start and goal arm errors, crossed inactivation only increased goal arm errors, leaving the frequency of start arm errors unaffected. These error patterns suggest that different memory computations engage different interactions between the hippocampus and extrahippocampal circuits, and that interactions with the mPFC are especially important for recent, as opposed to long-term, memory processing.

Like bilateral mPFC inactivation, crossed mPFC-vHPC inactivation tended to impair reversal more than discrimination learning, suggesting that flexible processing of recent spatial memory depends on interactions between these structures. Direct inputs from the vHPC may relay spatial information to the mPFC and support flexible rule encoding or other computations that reduce proactive interference and guide reversal learning (Spellman et al., 2015; also see Miller & Cohen, 2001). In turn, the mPFC may guide spatial processing in the HPC, for example, by selecting among prospective codes that guide goal selection (Guise & Shapiro, 2017). The mPFC influences the HPC via multisynaptic connections through the entorhinal cortex as well as the nucleus reuniens and rhomboid nucleus of the thalamus (Ito et al., 2015; Prasad & Chudasama, 2013; Vertes et al., 2007). The nucleus reuniens appears to be crucial for mPFC-HPC communication during spatial memory processing: reuniens inactivation impairs performance in flexible spatial memory tasks (Hembrook & Mair, 2011; Layfield, Patel, Hallock, & Griffin, 2015; Maisson, Gemzik, & Griffin, 2018) and degrades prospective spatial coding in dorsal CA1 neuronal activity (Ito et al., 2015), resembling effects of mPFC inactivation (Guise & Shapiro, 2017). Local field potentials may organize communication between the mPFC and HPC during flexible spatial memory processing, including theta (Jones & Wilson, 2005) and gamma (Spellman et al., 2015) oscillations, as well as sharp wave ripples (Jadhav et al., 2016).

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

The results show that flexible spatial learning in the plus maze requires both the HPC and PFC. Distributed circuits along the longitudinal axis of the HPC perform computations required for spatial learning and memory, and mPFC computations are needed to track contingency changes and overcome proactive interference. The results of crossed inactivation show that the flexible use of spatial memory requires either direct or indirect interactions between the mPFC and both the dorsal and ventral subregions of the HPC in at least one hemisphere. Such interactions likely include the transmission of spatial and contextual signals from the vHPC to the mPFC, and the transmission of rule information computed by the mPFC to the HPC (e.g., via the nucleus reuniens). This bidirectional communication may allow rewarded episodes to activate context-associated rules in the mPFC that, in turn, activate selective prospective memory codes in the HPC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01MH073689, R01MH065658, and P50MH094263-05 to M.L.S.; T32GM007280 for P.D.A.’s training) and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. We thank Drs. Mark Baxter and Peter Rudebeck for helpful comments on the manuscript and Maojuan Zhang for technical help.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Apergis-Schoute J, Pinto A, & Paré D (2006). Ultrastructural organization of medial prefrontal inputs to the rhinal cortices. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Deacon RMJ, Offen S, Friswell J, Grubb M, & Rawlins JNP (2002). Double dissociation of function within the hippocampus: Spatial memory and hyponeophagia. Behavioral Neuroscience, 116, 884–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Rawlins JN, McHugh SB, Deacon RMJ, Yee BK, Bast T, … Feldon J (2004). Regional dissociations within the hippocampus—Memory and anxiety. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 28, 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Yee BK, Good MA, Heupel MJ, Iversen SD, & Rawlins JN (1999). Double dissociation of function within the hippocampus: A comparison of dorsal, ventral, and complete hippocampal cytotoxic lesions. Behavioral Neuroscience, 113, 1170–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel JC, de Vasconcelos AP, Loureiro M, Cholvin T, Dalrymple-Alford JC, & Vertes RP (2013). The reuniens and rhomboid nuclei: Neuroanatomy, electrophysiological characteristics and behavioral implications. Progress in Neurobiology, 111, 34–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenquizca LA, & Swanson LW (2007). Spatial organization of direct hippocampal field CA1 axonal projections to the rest of the cerebral cortex. Brain Research Reviews, 56, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q, & Gold PE (2003). Intra-hippocampal lidocaine injections impair acquisition of a place task and facilitate acquisition of a response task in rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 144, 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchwell JC, & Kesner RP (2011). Hippocampal-prefrontal dynamics in spatial working memory: Interactions and independent parallel processing. Behavioural Brain Research, 225, 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, & Kesner RP (1988). Caudate nucleus and memory for egocentric localization. Behavioral and Neural Biology, 49, 332–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, & Aggleton JP (2000). Effects of selective excitotoxic prefrontal lesions on acquisition of nonmatching- and matching-to-place in the T-maze in the rat: Differential involvement of the prelimbic-infralimbic and anterior cingulate cortices in providing behavioural flexibility. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 12, 4457–4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H (2004). Hippocampus: Cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron, 44, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC (1991). On Fisher’s method of combining p-values. Biometrical Journal, 33, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, & Dong HW (2010). Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron, 65, 7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbinteanu J (2016). Contributions of hippocampus and striatum to memory-guided behavior depend on past experience. The Journal of Neuroscience, 36, 6459–6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbinteanu J, & McDonald RJ (2000). Dorsal and ventral hippocampus: Same or different? Psychobiology, 28(3), 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- Ferbinteanu J, & Shapiro ML (2003). Prospective and retrospective memory coding in the hippocampus. Neuron, 40, 1227–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbinteanu J, Shirvalkar P, & Shapiro ML (2011). Memory modulates journey-dependent coding in the rat hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 9135–9146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Seamans JK, & Phillips AG (1997). Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical, and ventral striatal circuits in radialarm maze tasks with or without a delay. The Journal of Neuroscience, 17, 1880–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, & Grace AA (2008). Dopamine modulation of hippocampal-prefrontal cortical interaction drives memory-guided behavior. Cerebral Cortex, 18, 1407–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guise KG, & Shapiro ML (2017). Medial prefrontal cortex reduces memory interference by modifying hippocampal encoding. Neuron, 94, 183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembrook JR, & Mair RG (2011). Lesions of reuniens and rhomboid thalamic nuclei impair radial maze win-shift performance. Hippocampus, 21, 815–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WB, & Vertes RP (2007). Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Structure & Function, 212, 149–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WB, & Vertes RP (2012). Collateral projections from nucleus reuniens of thalamus to hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: A single and double retrograde fluorescent labeling study. Brain Structure & Function, 217, 191–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PR, & Aggleton JP (1998). Neurotoxic lesions of the dorsomedial thalamus impair the acquisition but not the performance of delayed matching to place by rats: A deficit in shifting response rules. The Journal of Neuroscience, 18, 10045–10052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito HT, Zhang S, Witter MP, Moser EI, & Moser MB (2015). A prefrontal-thalamo-hippocampal circuit for goal-directed spatial navigation. Nature, 522, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav SP, Rothschild G, Roumis DK, & Frank LM (2016). Coordinated excitation and inhibition of prefrontal ensembles during awake hippocampal sharp-wave ripple events. Neuron, 90, 113–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM, Glowinski J, & Thierry A-M (1989). Selectivity of the hippocampal projection to the prelimbic area of the prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Research, 505, 337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM, & Witter MP (1991). Distribution of hippocampal CA1 and subicular efferents in the prefrontal cortex of the rat studied by means of anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 313, 574–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MW, & Wilson MA (2005). Theta rhythms coordinate hippocampal - Prefrontal interactions in a spatial memory task. PLoS Biology, 3, 2187–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung MW, Wiener SI, & McNaughton BL (1994). Comparison of spatial firing characteristics of units in dorsal and ventral hippocampus of the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience, 14, 7347–7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjelstrup KB, Solstad T, Brun VH, Hafting T, Leutgeb S, Witter MP, … Moser MB (2008). Finite scale of spatial representation in the hippocampus. Science, 321, 140–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski RW, Garcia CG, Wilson A, Hattori S, Howard MW, & Eichenbaum H (2013). Ventral hippocampal neurons are shaped by experience to represent behaviorally relevant contexts. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 8079–8087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley K (1950). In search of the engram In Society for Experimental Biology (1950). Physiological mechanisms in animal behavior. Society’s Symposium IV (pp. 454–482). Oxford, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Layfield DM, Patel M, Hallock H, & Griffin AL (2015). Inactivation of the nucleus reuniens/rhomboid causes a delay-dependent impairment of spatial working memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 125, 163–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharjan DM, Dai YY, Glantz EH, & Jadhav SP (2018). Disruption of dorsal hippocampal—Prefrontal interactions using chemogenetic inactivation impairs spatial learning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 155, 351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisson DJN, Gemzik ZM, & Griffin AL (2018). Optogenetic suppression of the nucleus reuniens selectively impairs encoding during spatial working memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 155, 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh SB, Deacon RMJ, Rawlins JNP, & Bannerman DM (2004). Amygdala and ventral hippocampus contribute differentially to mechanisms of fear and anxiety. Behavioral Neuroscience, 118, 63–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, & Cohen JD (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser MB, & Moser EI (1998). Distributed encoding and retrieval of spatial memory in the hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 18, 7535–7542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser MB, Moser EI, Forrest E, Andersen P, & Morris RG (1995). Spatial learning with a minislab in the dorsal hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 92, 9697–9701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2010). Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (8th ed.). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, & Nadel L (1978). The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Oxford: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly KC, Alarcon JM, & Ferbinteanu J (2014). Relative contributions of CA3 and medial entorhinal cortex to memory in rats. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, & McGaugh JL (1996). Inactivation of hippocampus or caudate nucleus with lidocaine differentially affects expression of place and response learning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 65, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, & Watson C (2007). The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates (6th ed.). London: Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters GJ, David CN, Marcus MD, & Smith DM (2013). The medial prefrontal cortex is critical for memory retrieval and resolving interference. Learning & Memory, 20, 201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters GJ, & Smith DM (2013). The medial prefrontal cortex is needed for resolving interference even when there are no changes in task rules and strategies. Behavioral Neuroscience, 134, 15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothuizen HHJ, Zhang WN, Jongen-Rêlo AL, Feldon J, & Yee BK (2004). Dissociation of function between the dorsal and the ventral hippocampus in spatial learning abilities of the rat: A within-subject, within-task comparison of reference and working spatial memory. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 19, 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad JA, & Chudasama Y (2013). Viral tracing identifies parallel disynaptic pathways to the hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 8494–8503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino ME, Detrick S, & Kesner RP (1999). Involvement of the prelimbic-infralimbic areas of the rodent prefrontal vortex in behavioral flexibility for place and response learning. The Journal of Neuroscience, 19, 4585–4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino ME, Kim J, Hassert D, Minniti N, & Kiang C (2003). The contribution of the rat prelimbic-infralimbic areas to different forms of task switching. Behavioral Neuroscience, 117, 1054–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman T, Rigotti M, Ahmari SE, Fusi S, Gogos JA, & Gordon JA (2015). Hippocampal-prefrontal input supports spatial encoding in working memory. Nature, 522, 309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR (1992). Memory and the hippocampus: A synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychological Review, 99, 195–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange BA, Witter MP, Lein ES, & Moser EI (2014). Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 15, 655–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW (1981). A direct projection from Ammon’s horn to prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Research, 217, 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP (2002). Analysis of projections from the medial prefrontal cortex to the thalamus in the rat, with emphasis on nucleus reuniens. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 442, 163–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP, Hoover WB, Szigeti-Buck K, & Leranth C (2007). Nucleus reuniens of the midline thalamus: Link between the medial prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus. Brain Research Bulletin, 71, 601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G-W, & Cai J-X (2006). Disconnection of the hippocampal-prefrontal cortical circuits impairs spatial working memory performance in rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 175, 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G-W, & Cai J-X (2008). Reversible disconnection of the hippocampal-prelimbic cortical circuit impairs spatial learning but not passive avoidance learning in rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 90, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Kapeller-Libermann D, Travaglia A, Inda MC, & Alberini CM (2017). Direct dorsal hippocampal-prelimbic cortex connections strengthen fear memories. Nature Neuroscience, 20, 52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]