Abstract

Pathogen identification is a critical step during diagnosis of infectious diseases. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-Of-Flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) has become the gold standard for identification of microorganisms cultured on solid media in microbiology laboratories. Direct identification of microbes from liquid specimen, circumventing the need for the additional overnight cultivation step, has been successfully established for blood culture, urine and liquor. Here, we evaluate the ability of MALDI-TOF MS for direct identification of pathogens in synovial fluid after liquid enrichment in BacT/Alert blood culture bottles. Influence of synovial specimen quality on direct species identification with the MALDI BioTyper/Sepsityper was tested with samples inoculated from pretested native synovia with concomitant inoculation of blood or pus, or highly viscous fluid. Here, we achieved >90% concordance with culture on solid medium, and only mixed-species samples posed significant problems. Performance in routine diagnostics was tested prospectively on bottles inoculated by treating physicians on ward. There, we achieved >70% concordance with culture on solid media. The major contributors to test failure were the absence of a measurable mass signal and mixed-specimen samples. The Sepsityper workflow worked well on samples derived from BacT/Alert blood culture bottles inoculated with synovial fluid, giving concordant results to identification from solid media. Host remnant material in the inoculum, such as blood or pus, had no detrimental effect on identification score values of the BioTyper system after processing with the Sepsityper workflow, and neither had the initial viscosity of the synovial sample.

Introduction

Over the last decades, the numbers of prosthetic joint replacements have continuously increased and are forecast to increase even further with the ageing population [1]. This in turn correlates with a higher number of associated prosthetic joint infections (PJIs). Implant-associated infections have significant consequences on morbidity and mortality and place a high economic burden on the healthcare system [2].

For focused therapy of PIJ, identification of pathogens from synovial fluid is highly relevant. Consequently, aspiration of synovial fluid with microbiological analysis is recommended by the AAOS guide-lines for joint infections [3]. However, several challenges exist in the diagnostic procedures of PJI. Most importantly, samples in association with PJI or bone infections after fracture fixation generally have low bacterial densities with concomitant cellular debris, so that direct bacterial identification out of these samples is difficult [4]. Enrichment steps, e.g. in liquid medium and prolonged incubation (up to 2 weeks), increase sensitivity and specificity [5,6]. They allow observance of slow growing small colony variants [7] or fastidious bacteria, and lead to improved diagnosis [8]. Any possible reduction in processing time will likely have a positive effect on treatment.

For microbes cultured on solid media, Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has become the gold standard for species identification. This technology has brought significant changes in processing of microbiological probes and replaced most cost- and time intensive phenotypic biochemical assays. For identifying microbial species out of liquid culture, MALDI-TOF is already regularly used for blood specimen (reviewed in [9,10]) and is highly standardized during routine diagnostics through commercialized assays such as the Sepsityper workflow [11]. These procedures circumvent the need for an additional overnight cultivation step. A first study has demonstrated the feasibility of such assays also for orthopedic samples using the BACTEC system [12].

Here, we examined whether BacT/Alert blood culture vials inoculated with synovial fluid were suitable for the Sepsityper workflow, if this yielded microbial identification concordant with the standard culture procedure, and if different levels of host residue influence these results.

Results and discussion

Several experimental factors influence MALDI-TOF mass spectrum quality when bacteria are analyzed from clinical samples. Residual host material ionizes along with microbial markers. If the host material is in excess, this can lead to spectra representing the host rather than the microbe. Consequently, a main goal of sample pre-processing is eliminating host material, and enriching for microbial cells. A possible option is amplification through liquid culture. This may however introduce several components into the sample interfering with the MALDI-TOF process [13]. In older blood culture systems, charcoal and salt ions from the culture media were shown to interfere with the results [14]. Even after successful amplification, liquid cultures will still contain remnants of host materials, such as blood or tissue cells, soluble proteins, or mucus. These materials generate background noise mass peaks, overlapping with microbial spectra and interfere with the interpretation of bacterial proteome profiles [15]. Therefore, amplicon pretreatment removing host cells and proteins, while further concentrating the microbes, improves spectrum quality.

To test if the residues contained in synovial inoculum had an influence of species identification, we used a total of 23 native synovial samples (Table 1) over a course of 5 weeks, which contained a visible degree of host residue (blood, pus), or were highly viscous. The samples had been analyzed by culture on solid media and were additionally inoculated into pediatric BacT/Alert blood culture bottles. All bottles automatically flagged positive by the next morning (~16h). Using the Sepsityper workflow, 21/23 (91%) of the samples gave concordant results with culture on solid media. Out of these, only two missed the manufacturer-recommended threshold of 2.000 for species-level identifications. Acceptance of lower score values down to 1.700 when using the Sepsityper protocol, however, appear feasible [9]. The two remaining samples (9%) were from mixed-species specimens. In one case (#11) the initial mixed result could not be confirmed by reanalysis, and the Sepsityper identification was concordant with this second culture result (Table 1). Most importantly, there was no apparent hindrance through blood, pus, or high viscosity present in the inoculum.

Table 1. Results of spiked culture Sepsityper identification.

| Nr. | consistency | joint | routine identification | score | Sepsityper identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| concordant identification to species level (Score ≥ 2) | |||||

| 1 | blood, viscous | hip | Enterobacter cloacae | 2.47 | Enterobacter cloacae |

| 2 | blood, pus | hip | Streptococcus agalactiae | 2.30 | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| 3 | blood, pus | hip | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.19 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 5 | blood, viscous | spine | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.24 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 6 | pus | spine | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.13 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 7 | blood | hip | Streptococcus pyogenes | 2.44 | Streptococcus pyogenes |

| 9 | blood, viscous | hip | Enterococcus faecium | 2.00 | Enterococcus faecium |

| 10 | blood, pus | n.r. | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.33 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 12 | blood, viscous | knee | Escherichia coli | 2.39 | Escherichia coli |

| 13 | blood, viscous | n.r. | Escherichia coli | 2.30 | Escherichia coli |

| 14 | clear, viscous | knee | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.34 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 15 | clear, viscous | knee | Escherichia coli | 2.28 | Escherichia coli |

| 16 | pus | knee | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.37 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 17 | clear, viscous | knee | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.39 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 18 | pus | knee | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.37 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 19 | pus, viscous | n.r. | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.29 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 20 | pus, viscous | hip | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2.16 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| 21 | pus, viscous | knee | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2.03 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| 22 | blood | knee | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2.23 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| concordant identification to species level, but only with genus level scores (≥ 1.7–1.999) | |||||

| 4 | blood, pus | hip | Staphylococcus aureus | 1.97 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 8 | blood, viscous | knee | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1.99 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| mixed cultures | |||||

| 11 | blood, pus | n.r. | Candida albicans / C. parapsilosis | 2.14 | Candida parapsilosis |

| 23 | blood, viscous | hip | Escherichia coli / Enterococcus faecalis | 1.57 | no reliable identification |

n.r. not recorded.

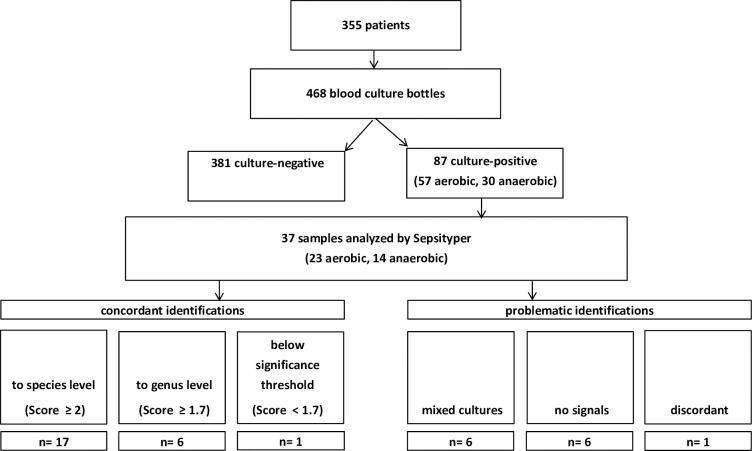

In order to test if this procedure also worked outside artificial laboratory conditions, we prospectively applied it on positively flagged specimen from our routine diagnostics. There, specimen had been inoculated on ward by the treating physician, and the specific condition of the inoculum was unknown (Fig 1). A total of 468 blood culture bottles inoculated with synovia from 355 clinical specimens were received during the study period, out of which 87 were flagged positive. Fifty bottles were excluded because they were not made immediately available for the study, mainly because they flagged positive during the night during the night leading to unrepresentatively high microbial yield, leaving 37 bottles to be tested by the Sepsityper workflow.

Fig 1. Prospective study scheme.

Pathogen identification concordant with results from isolates cultured on solid agar was achieved in 30/37 (81%) samples at the first try, however 7/37 (19%) again not at levels required for species-level identifications. One sample gave discordant species-level matches for the bottle (Streptococcus mitis) and solid agar (Streptococcus pneumoniae). Reliable distinction of S. pneumoniae from viridans group streptococci is important because of the different pathogenic properties of these organisms, and this has also previously been achieved by MALDI-TOF MS by others [16].

Five out of 37 samples (14%) contained mixed-species cultures of either Staphylococcus aureus combined with different enterobacteria, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa combined with Entercoccus faecieum (4 samples of the same patient). Mixed cultures have previously been shown to be problematic, where the ration of the organisms is unequal [17,18]. Among our samples, only in one the result indicated a mixed culture with both species, in the other four only a single species was found with high score values, however, plating of the culture indicated no more than 4-fold differences in cfu between each of the two species present. In the six remaining samples, identification was not achieved due to the complete lack of mass signals, potentially attributable to the loss of the bacterial pellet or too low cell counts in the culture (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of prospective Sepsityper identification.

| Type of blood vial | Location/ Joint | side | bacterial species identified from direct ID by Sepsityer | MALDI-TOF score | Reference identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| concordant species-level identification (score ≥ 2) | |||||

| aerobic | hip | left | Streptococcus agalactiae | 2.51 | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| aerobic | knee | left | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | 2.18 | Staphylococcus lugdunensis |

| aerobic | knee | left | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | 2.29 | Staphylococcus lugdunensis |

| aerobic | hip | right | Staphylococcus capitis | 2.19 | Staphylococcus capitis |

| aerobic | elbow | left | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.44 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| aerobic | hip | left | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | 2.10 | Streptococcus dysgalactiae |

| aerobic | knee | right | Staphylococcus capitis | 2.13 | Staphylococcus capitis |

| aerobic | hip | right | Escherichia coli | 2.41 | Escherichia coli |

| aerobic | knee | right | Streptococcus agalactiae | 2.00 | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| aerobic | hip | right | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.37 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| aerobic | shoulder | right | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | 2.01 | Streptococcus dysgalactiae |

| aerobic | knee | right | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2.24 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| aerobic | knee | right | Escherichia coli | 2.56 | Escherichia coli |

| anaerobic | hip | left | Propionibacterium acnes | 2.25 | Propionibacterium acnes |

| anaerobic | knee | left | Propionibacterium acnes | 2.41 | Propionibacterium acnes |

| anaerobic | knee | left | Propionibacterium acnes | 2.37 | Propionibacterium acnes |

| anaerobic | hip | right | Enterobacter cloacae | 2.42 | Enterobacter cloacae |

| anaerobic | knee | left | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2.11 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| concordant species-level identification, but only with genus level scores (≥ 1.7–1.999) | |||||

| aerobic | hip | left | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1.85 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| aerobic | knee | left | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1.71 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| anaerobic | knee | left | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1.96 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| anaerobic | knee | left | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | 1.75 | Streptococcus dysgalactiae |

| anaerobic | hip | left | Propionibacterium acnes | 1.70 | Propionibacterium acnes |

| aerobic | hip | left | Streptococcus constellatus | 1.98 | Streptococcus constellatus |

| concordant species-level identification, but with scores below significance threshold (< 1.7) | |||||

| aerobic | knee | left | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1.65 | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| discordant species complex-level identifications | |||||

| anaerobic | hip | right | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2.08 | Streptococcus oralis |

| Mixed cultures | |||||

| aerobic | hip | left | Staphylococcus aureus | 2.29 | S. aureus, E. cloacae, E. kobei |

| aerobic | hip | right | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2.23 | P. aeruginosa, E. faecium |

| anaerobic | hip | right | Enterococcus faecium | 2.41 | Enterococcus faecium |

| aerobic | hip | right | Enterococcus faecium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2.17 | Enterococcus faecium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| 2.03 | |||||

| anaerobic | hip | right | Enterococcus faecium | 2.40 | Enterococcus faecium |

| no identification | |||||

| aerobic | hip | right | no peaks found | n.a. | Campylobacter coli |

| aerobic | hip | right | no peaks found | n.a. | Streptococcus oralis |

| aerobic | hip | right | no peaks found | n.a. | Streptococcus oralis |

| aerobic | hip | right | no peaks found | n.a. | Staphylococcus aureus |

| anaerobic | shoulder | n.r. | no peaks found | n.a. | Staphylococcus aureus |

| anaerobic | knee | left | no peaks found | n.a. | Propionibacterium acnes |

n.r., not recorded, n.a. not applicable.

Conclusion

In summary, the Sepsityper workflow also worked well on mono-species samples derived from BacT/Alert blood culture bottles inoculated with synovia. The major contributor to failed detection was the absence of mass signals. The level of concordant identifications in both our specimen groups was comparable to those achieved by others for synovia [12], or blood cultures (summarized in [9,10]). In the case of mixed cultures, the test was not able to reliably detect the mixture, despite apparent similar cfu numbers. Host remnant material in the inoculum, such as blood or pus, had no detrimental effect on identification score values of the MALDI BioTyper system, and neither had the initial viscosity of the synovial sample.

Materials and methods

Sample acquisition and study design

For assessment of method feasibility, pediatric aerobic FCS-supplemented blood culture vials (BacT/ALERT PF Plus bioMérieux, Nürtingen, Germany) were inoculated with refrigerated synovial fluid that was previously found to be culture positive by our routine diagnostic procedures. Samples were selected on the basis that they had to be viscous, ideally with large proportions of blood and/or pus. Positively flagged culture vials were processed by MALDI-TOF MS as described below.

For prospective study, we used blood culture specimens, where the vials had been routinely inoculated by treating physicians with synovial fluid, transported to the microbiology lab, and cultivated in an automated microbial detection system (BacT/ALERT3D, bioMérieux) for up to 14 days. Only those samples that were made available for the study without delay were included for downstream processing by MALDI-TOF. The collection period was January 01, 2018 to March 07, 2019.

Routine culture

Standard microbiological cultures were performed on all specimen included into the study by plating on Columbia agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood (bioMérieux) under aerobic conditions, on Chocolate agar (bioMérieux) under atmosphere enriched with 9% C02 for 48h and, under anaerobic conditions on Columbia agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood (bioMérieux) for 48 h at 37°C. Reference identifications from culture plates were performed using the same MALDI Biotyper system as below, using standard procedures.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis

Direct processing of the samples with the Sepsityper kit (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions and as described in the literature for blood cultures [19]. In detail, 1 mL of the medium from a positive blood culture bottle was mixed with 200 μL of the lysis reagent and thoroughly mixed for 10 sec. After short incubation at room temperature, this mixture was passed over a spin column (Sigma-Aldrich, SC1000-1KT) for 2 minutes at 2000 rpm in a table top centrifuge and the filter discarded. Microbial cells were harvested from the flow through by centrifugation 1 min at 11500 xg. The supernatant was removed by aspiration and discarded, and the pellet washed with 1 mL saline. After further centrifugation, the supernatant was decanted and the pellet was re-suspended to 300 μL with deionized water. After addition of 900 μL 100% ethanol the cells were again harvested by centrifugation for 2 min at 11500 xg. The supernatant then was decanted, any residual ethanol then was removed and the pellet was dried at room temperature.

For extraction, 70% formic acid and an equal volume of 100% acetonitrile were added to the pellet and each mixed carefully. The sample was centrifuged for 2 min at maximum speed and 1 μL of the supernatant then was transferred to a sample spot on a MALDI target plate. After the sample spot had air dried it was overlaid with 1 μL matrix solution (Bruker Daltonics) and dried again. Three spots on the MALDI target plate were used for each sample. Afterwards identification of species was performed using a MALDI BioTyper SMART system using the standard settings (Bruker Daltonics, database version 2018).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethical board on the University Medical Center Göttingen (approval number 17/11/29; version 2.0). Patients have given written consent to participate in studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge contributions of clinical and routine diagnostic laboratory staff for acquisition and processing of diagnostic specimen. Specifically, the authors thank Sabine Ceramella and Yvonne Laukat for expert technical assistance.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was supported through a grant of the AO Trauma foundation (grant number FP00006675_SA002) through the AOT CPP program. Conceived the study: CN, UG, AS, FTB, OB Provided samples: CN, MW, AS, FTB Performed experiments: AN, PS Evaluated data: CN, AN, OB Wrote the manuscript: CN, AN, OB.

References

- 1.Leitner L, Turk S, Heidinger M, Stockl B, Posch F, Maurer-Ertl W, et al. Trends and Economic Impact of Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in Central Europe: Findings from the Austrian National Database. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4707 10.1038/s41598-018-23266-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metsemakers WJ, Kuehl R, Moriarty TF, Richards RG, Verhofstad MHJ, Borens O, et al. Infection after fracture fixation: Current surgical and microbiological concepts. Injury. 2018;49(3):511–22. 10.1016/j.injury.2016.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parvizi J, Della Valle CJ. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline: diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(12):771–2. 10.5435/00124635-201012000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lallemand E, Coiffier G, Arvieux C, Brillet E, Guggenbuhl P, Jolivet-Gougeon A. MALDI-TOF MS performance compared to direct examination, culture, and 16S rDNA PCR for the rapid diagnosis of bone and joint infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(5):857–66. 10.1007/s10096-016-2608-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Font-Vizcarra L, Garcia S, Martinez-Pastor JC, Sierra JM, Soriano A. Blood culture flasks for culturing synovial fluid in prosthetic joint infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(8):2238–43. 10.1007/s11999-010-1254-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen LH, Lange J, Xu Y, Schonheyder HC. Optimizing culture methods for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections: a summary of modifications and improvements reported since 1995. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2012;61(Pt 3):309–16. 10.1099/jmm.0.035303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogut A, Niedzwiadek J, Koziol-Montewka M, Strzelec-Nowak D, Blacha J, Mazurkiewicz T, et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphyloccocus warneri small-colony variants associated with prosthetic-joint infections. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2014;63(Pt 2):176–85. 10.1099/jmm.0.066068-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schafer P, Fink B, Sandow D, Margull A, Berger I, Frommelt L. Prolonged bacterial culture to identify late periprosthetic joint infection: a promising strategy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;47(11):1403–9. 10.1086/592973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott JS, Sterling SA, To H, Seals SR, Jones AE. Diagnostic performance of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry in blood bacterial infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infectious diseases (London, England). 2016;48(7):530–6. 10.3109/23744235.2016.1165350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Aragon J, Ballestero-Tellez M, Gutierrez-Gutierrez B, de Cueto M, Rodriguez-Bano J, Pascual A. Direct bacterial identification from positive blood cultures using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017. 10.1016/j.eimc.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgenthaler NG, Kostrzewa M. Rapid identification of pathogens in positive blood culture of patients with sepsis: review and meta-analysis of the performance of the sepsityper kit. International journal of microbiology. 2015;2015:827416 10.1155/2015/827416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lallemand E, Arvieux C, Coiffier G, Polard JL, Albert JD, Guggenbuhl P, et al. Use of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry after liquid enrichment (BD Bactec) for rapid diagnosis of bone and joint infections. Res Microbiol. 2017;168(2):122–9. 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabados F, Michels M, Kaase M, Gatermann S. The sensitivity of direct identification from positive BacT/ALERT (bioMerieux) blood culture bottles by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry is low. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(2):192–5. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03229.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riederer K, Cruz K, Shemes S, Szpunar S, Fishbain JT. MALDI-TOF identification of Gram-negative bacteria directly from blood culture bottles containing charcoal: Sepsityper(R) kits versus centrifugation-filtration method. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2015;82(2):105–8. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuchida S, Murata S, Miyabe A, Satoh M, Takiwaki M, Matsushita K, et al. An improved in-house lysis-filtration protocol for bacterial identification from positive blood culture bottles with high identification rates by MALDI-TOF MS. Journal of microbiological methods. 2018;148:40–5. 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harju I, Lange C, Kostrzewa M, Maier T, Rantakokko-Jalava K, Haanpera M. Improved Differentiation of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Other S. mitis Group Streptococci by MALDI Biotyper Using an Improved MALDI Biotyper Database Content and a Novel Result Interpretation Algorithm. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(3):914–22. 10.1128/JCM.01990-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortelmaier C, Panda S, Robertson I, Krell M, Christodoulou M, Reichardt N, et al. Identification performance of MALDI-ToF-MS upon mono- and bi-microbial cultures is cell number and culture proportion dependent. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2019;411(26):7027–38. 10.1007/s00216-019-02080-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeve MA, Bachmann D. MALDI-TOF MS protein fingerprinting of mixed samples. Biol Methods Protoc. 2019;4(1):bpz013 10.1093/biomethods/bpz013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schubert S, Weinert K, Wagner C, Gunzl B, Wieser A, Maier T, et al. Novel, improved sample preparation for rapid, direct identification from positive blood cultures using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13(6):701–6. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.