Abstract

Bacteria and Candida albicans are prominent gut microbiota, and the translocation of these organisms into blood circulation might induce mixed-organism biofilms, which warrants the exploration of mixed- versus single-organism biofilms in vitro and in vivo. In single-organism biofilms, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) produced the least and the most prominent biofilms, respectively. C. albicans with P. aeruginosa (PA+CA) induced the highest biofilms among mixed-organism groups as determined by crystal violet straining. The sessile form of PA+CA induced higher macrophage responses than sessile PA, which supports enhanced immune activation toward mixed-organism biofilms. In addition, Candida incubated in pre-formed Pseudomonas biofilms (PA>CA) produced even higher biofilms than PA+CA (simultaneous incubation of both organisms) as determined by fluorescent staining on biofilm matrix (AF647 color). Despite the initially lower bacteria during preparation, bacterial burdens by culture in mixed-organism biofilms (PA+CA and PA>CA) were not different from biofilms of PA alone, supporting Candida-enhanced Pseudomonas growth. Moreover, proteomic analysis in PA>CA biofilms demonstrated high AlgU and mucA with low mucB when compared with PA alone or PA+CA, implying an alginate-related mucoid phenotype in PA>CA biofilms. Furthermore, mice with PA>CA biofilms demonstrated higher bacteremia with more severe sepsis compared with mice with PA+CA biofilms. This is possibly due to the different structures. Interestingly, l-cysteine, a biofilm matrix inhibitor, attenuated mixed-organism biofilms both in vitro and in mice. In conclusion, Candida enhanced Pseudomonas alginate–related biofilm production, and Candida presentation in pre-formed Pseudomonas biofilms might alter biofilm structures that affect clinical manifestations but was attenuated by l-cysteine.

Keywords: biofilms, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans, l-cysteine, alginate

Introduction

Biofilms are a community of microorganisms that grow on both nonliving and biotic surfaces to survive in harsh environments by producing multilayers of high-abundance extracellular matrix (ECM) consisting of proteins, polysaccharides, and nucleic acids (Flemming et al., 2007; de Kievit, 2009; Ghafoor et al., 2011; Flemming et al., 2016). Biofilms consist of 85% (by volume) matrix materials and 15% microbial cells (Flemming et al., 2007; Rasamiravaka et al., 2015). Surface-adherent (sessile) bacteria in biofilms become more antibiotic resistant than the free living (planktonic) form and result in recurrent infections (Darouiche et al., 2002; Aslam and Darouiche, 2011). Biofilms also possibly form nidus at the surface for the attachment of other pathogens that lead to biofilms of multiple bacteria or multiorganisms (Yang et al., 2011). The communication in mixed-organism biofilms is referred to as “quorum sensing” (Hossain et al., 2020) and might induce different biofilm properties than single-organism biofilms (Yang et al., 2011). Although catheter-related colonization of Gram-positive bacteria from skin microbiota (Streptococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp.) is common, biofilms in the inner lumen of the catheter consist of both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria (Murga et al., 2001).

Both Gram-negative bacteria and C. albicans are the most and the second most predominant intestinal human microbiota, respectively, in which the natural interactions between these organisms is possible (Amornphimoltham et al., 2019). Because i) the translocation of gut microbiota (e.g., Enterococcus spp., Gram-negative bacteria, and Candida albicans) into blood circulation during sepsis (Alexandraki and Palacio, 2010; Amornphimoltham et al., 2019) and catheter-related candidiasis (Almirante et al., 2005; Tumbarello et al., 2012) are common, ii) mixed systemic infection between bacteria and Candida spp. is more severe than the infection by each organism separately (Bouza et al., 2013a; Bouza et al., 2013b; Dhamgaye et al., 2016), and iii) biofilms could be formed during bacteremia and fungemia (Shin et al., 2002; Li et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2018); mixed-organism biofilms from bacteria and Candida spp. during sepsis are possible. Indeed, there is interaction between Candida albicans and Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli (in peritonitis), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (in cystic fibrosis and ventilation-associated pneumonia), and Acinetobacter baumannii (in ventilation-associated pneumonia) (Dhamgaye et al., 2016). In addition, the observation of enhanced biofilm production has been mentioned with preliminary crystal violet staining (El-Azizi et al., 2004; Mear et al., 2013). Gut leakage–induced Candida translocation during sepsis (Leelahavanichkul et al., 2016; Amornphimoltham et al., 2019) might induce biofilms of bacterial-fungal collaboration, which result in persistent, recurrent, or severe infection (Chen and Wen, 2011; Wu et al., 2015).

Because i) antibiotic resistance caused by biofilm is a current serious medical problem (Shahrour et al., 2019), ii) biofilm eradication (bacterial and fungi) is difficult, and iii) antimicrobial treatment without biofilm-removal results in recurrent or persistent infection (Gunn et al., 2016); interventions or drugs for biofilm prevention/eradication are necessary (O’Toole et al., 2015). Here, we explore the interaction between gut-derived bacteria and C. albicans in vitro and in a catheter-subcutaneous implantation mouse model with the exploration in macrophage responses and the anti-biofilm evaluation.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Animal Models

Animal care and use protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, based on the National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA. Male, 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice from Nomura Siam International (Pathumwan, Bangkok, Thailand) were purchased.

Organism Preparation

Due to the limitation on biofilm production of organisms from laboratory strains, gut-derived bacteria and Candida albicans were isolated from blood samples of patients from the King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital (Bangkok, Thailand) and the same strain of organisms was used in all of the experiments. The sample accession process was approved by the ethical institutional review board, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University according to the Declaration of Helsinki with written informed consent.

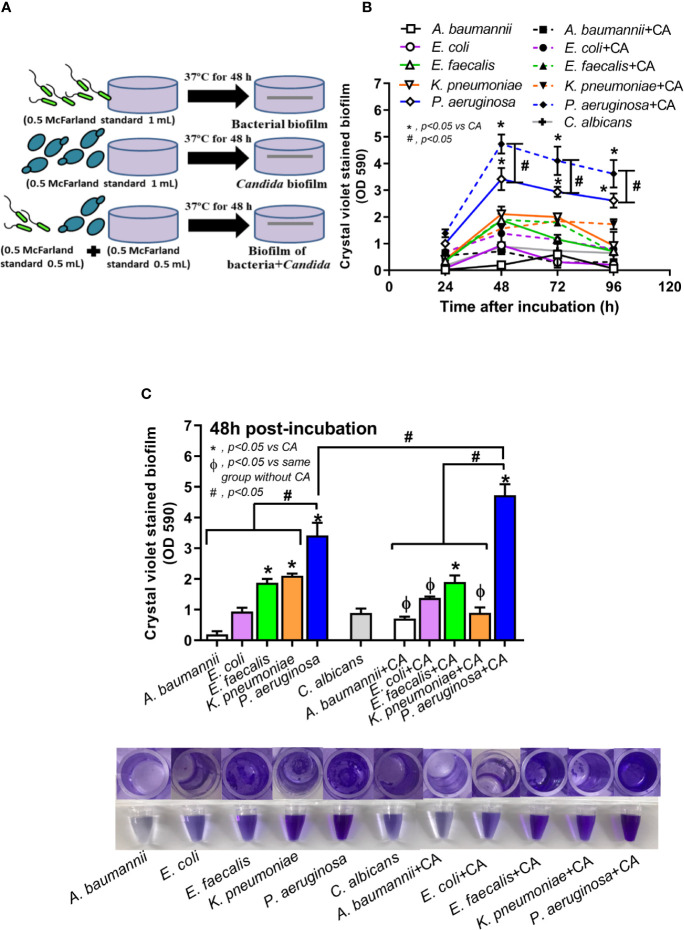

Biofilm Induction and Anti-Biofilms In Vitro

To obtain the organisms in the early stationary phase that is suitable for biofilm production (Ricicova et al., 2010), bacteria and C. albicans were grown in Tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) and Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB) (Oxoid), respectively, for 24 h at 37°C. Then, the samples were washed, resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), and adjusted to the turbidity of 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1 × 108 CFU/mL) in TSB. Then, the organisms were incubated at 37°C on 96-well plates (200 µL of TSB/well) for crystal violet staining and on microscope cover glasses (22x22 mm) (MenzelTM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or 25 mm segments of polyurethane catheter (NIPRO, Ayutthaya, Thailand) in 6-well plates (5 mL of TSB/well) for fluorescent staining. In the P. aeruginosa plus C. albicans group (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans), 0.5 mL of bacteria and C. albicans at 0.5 McFarland were combined into 1 mL for mixed-organism biofilm preparation, and 1 mL 0.5 McFarland was used for the preparation of single-organism biofilms ( Figure 1A ). Because C. albicans might be present on the previously formed bacterial biofilms, C. albicans administration after 24 h of P. aeruginosa incubation was performed (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans). The potential anti-biofilms l-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (Olofsson et al., 2003; El-Baky et al., 2014) and β-defensin 3 (Peptide institute, Inc., Ibaraki-Shi, Osaka, Japan) (Batoni et al., 2016) in different concentrations were preliminary tested for bactericidal effect incubation with the organisms in TSB (Oxiod) for bacterial burdens at 24 h by optic density 600 (OD 600) with spectrophotometry (absorbance reader; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). In addition, the anti-biofilms property of both molecules was tested by 96-well plate biofilms with crystal violet staining. Moreover, l-cysteine at 50 mM was incubated with the organisms for the determination of biofilms on cover glasses, catheters in incubator, and catheters in mice.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the experimental design demonstrated lower bacteria in the biofilm preparation of mixed bacteria and Candida (bacteria + C. albicans) when compared with single-organism biofilms (A), crystal violet–stained biofilm in 96-well plates from single- and mixed-organisms in the time course evaluation (B), and in the biofilms at 48 h post-incubation with representative pictures of crystal violet stained 96-well plates and the color with acetic acid elution (C) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined for statistical significance by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups (B, C). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed.) (*p<0.05; # p<0.05).

Biofilm Induction and Anti-Biofilms In Vivo

To determine in vivo biofilms, a mouse model of catheter subcutaneous-implantation following a previous publication was performed (Buret et al., 1991). In brief, 25-mm catheters (NIPRO) were incubated with organisms for 3 h at 37°C before washing with PBS and subcutaneously implanted onto the mouse flank on both sides under isoflurane anesthesis. In the P. aeruginosa > C. albicans group, P. aeruginosa were incubated with catheters for 1.5 h at 37°C before C. albicans administration and then further incubated for another 1.5 h before washing and inserting into mice. In the anti-biofilm test, l-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich) at 50 mM was incubated together with the organisms before subcutaneous insertion in mice. At 48 h after catheter insertion, mice were sacrificed with sample collection (blood and catheters) by cardiac puncture under isoflurane anesthesia. For survival analysis, mice were observed for 96 h after the insertion. Renal injury (serum creatinine) and liver damage (serum alanine transaminase) were determined by QuantiChrom Creatinine Assay (DICT-500) (Bioassay, Hayward, CA, USA) and EnzyChrom Alanine Transaminase assay (EALT-100, BioAssay), respectively. Serum cytokines were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Invitrogen).

Biofilm Visualization and Organism Burdens From Biofilms

In 96-well plates, crystal violet color was used for preliminary quantity estimation of biofilm ECM. Briefly, the supernatant in 96-well plates was discarded, stained with 0.1% crystal violet (200 µL) (Sigma-Aldrich) in water for 15 min, washed with water, and solubilized with 30% acetic acid (200 µL) (Sigma-Aldrich) in water before measurement with the absorbance reader (BioTek) with absorbance at 590 nm. For cover glasses and catheters after 48 h incubation, the samples were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 15 min, and stained for i) ECM by concanavalin AF647 (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, California, USA) at 50 μg/mL, ii) bacterial DNA with SYTO9 (Invitrogen) at 3.34 μM, and iii) fungi by calcofluor white (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 μg/mL for 30 min in the dark before visualization by LSM 800 Airyscan confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and Plan-Apochromat (Celldiscoverer7 LSM900 Airyscan2) for cover glass and catheter biofilms, respectively. Fluorescent intensity was then analyzed by ZEN imaging software (Carl Zeiss). To determine the organism burdens from biofilms, the biofilms were dissolved in normal saline (1 mL) and thoroughly vortexed for 5 min and then processed as follows: i) directly incubated in TSB (Oxioid) for bactericidal burdens evaluated by the absorbance reader (BioTek) with optical density 600 (OD 600) at 24 h at 37°C incubation or ii) directly plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA) or Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) (Oxoid) in serial dilutions for bacterial and fungal burdens, respectively, from the samples with a mixture of bacteria and fungi before colony enumeration at 48 h at 37°C incubation. Of note, characteristics of colonies from bacteria and fungi were distinguishable on culture agar plates.

Macrophage Cell-Line Experiments

RAW264.7, a mouse macrophage cell line, was used because immune activation toward organisms in a free-living form (planktonic cells) versus in biofilms (sessile form) might be different. As such, the sessile-form organisms were prepared in a cover-glass system and planktonic forms by culture in TSB. Then, both samples were heat inactivated at 65°C for 30 min before sonication with a high-intensity ultrasonic processor (VC/VCX 130, 500, 750) at 25% amplitude and centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min to separate the supernatant. Then, macrophages at 5x105 cells/well were incubated with the supernatant for 24 h before the evaluation of cytokines by ELISA (Invitrogen) and macrophage polarization by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Total RNA from macrophages was prepared by RNA easy mini-kit (Qiagen) and high-capacity reverse transcription assay (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-165 Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The relative quantitation normalized to β-actin (an endogenous housekeeping gene) by comparative threshold (delta-delta Ct) method (2-ΔΔCt) was demonstrated. The list of primers for PCR is presented in Supplementary Table 1 .

Determination of Bacterial Genes

Bacterial genes that associated with ECM were determined by PCR as previously published (Toyofuku et al., 2012). Briefly, the biofilms from cover glasses were scraped into 1 mL of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and then purified RNA was treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by random hexamer primers using reverse transcriptase (RevertAid First Strand cDNA, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and PCR performed as previously described. The relative quantitation normalized to the housekeeping 16S rRNA gene with the comparative cycle threshold against the expression in the P. aeruginosa group was demonstrated.

Proteomic Analysis

Proteins were precipitated with cold acetone from the equal volume of each condition, and the pellet was redissolved with urea (8 M) in 50 mM Tris‐HCl (pH = 8) to determine protein concentration by BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, the soluble proteins were mixed with dithiothreitol (DTT), alkylated by iodoacetamide (IAA), digested with trypsin, added trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to stop the digestion reaction, and dried by a SpeedVac centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, peptides were analyzed by the EASY-nLC1000 system coupled to a Q-Exactive Orbitrap Plus mass spectrometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min with 5%–40% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid (FA) for 70 min followed by a linear gradient from 40%–95% acetonitrile in 0.1% FA for 20 min. Liquid chromatography mass spectrometer (LC-MS) analysis was performed using a 10 data-dependent acquisition method with an MS scan range of 350–1,400 m/z accumulated at a resolution of 70,000 full width at half maximum (FWHM) followed by a resolution of 17,500 FWHM. The normalized collision energy of higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) was controlled at 32%. Precursor ions with unassigned charge state of +1 or those of greater than +8 were excluded, and the dynamic exclusion time was set to 30 s. Data acquisitions were monitored by Xcalibur 4.4 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptide spectrums were identified by SEQUEST-HT search engine against a mouse UniProt FASTA database. Searching parameters were i) digestion enzyme: trypsin, ii) maximum allowance for missed cleavages: 2, iii) maximum of modifications: 4, iv) fixed modifications: carbamidomethylation of cysteine (57.02146 Da), and v) variable modifications: oxidation of methionine (15.99491 Da). Biological process analysis of the host proteins was carried out using the PANTHER (http://www.pantherdb.org/) software program. Mass spectrometry proteomic data were determined and submitted to the ProteomeXchange consortium via the PRIDE (http://www.proteomexchange.org), and are available under the data set identifier PXD020949.

Statistical Analysis

Mean ± standard error (SE) was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined for statistical significance by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s analysis or Student’s t-test for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups, respectively. Survival analysis was performed by Log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 11.5 software (SPSS, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0 software (La Jolla, CA, USA). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Candida Enhances Pseudomonas Biofilms and Increases Macrophage Responses

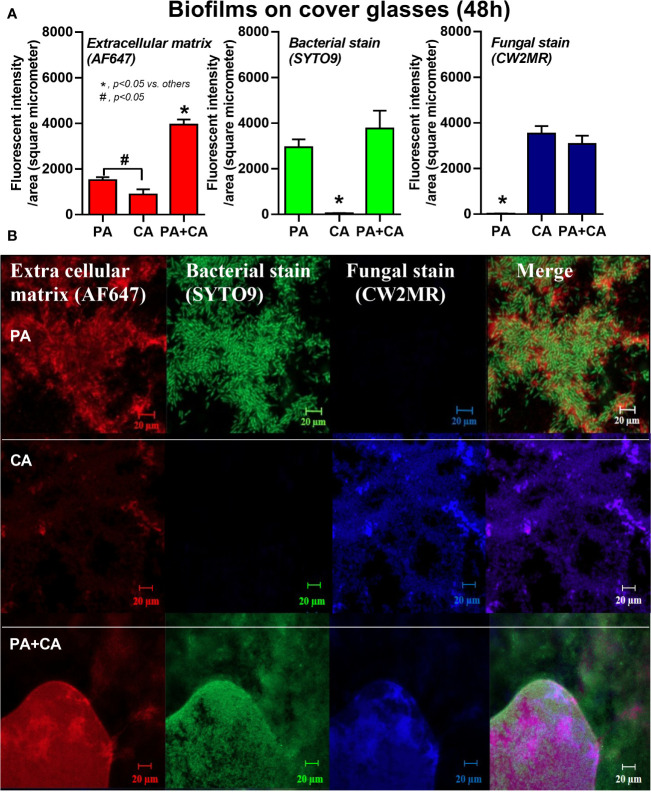

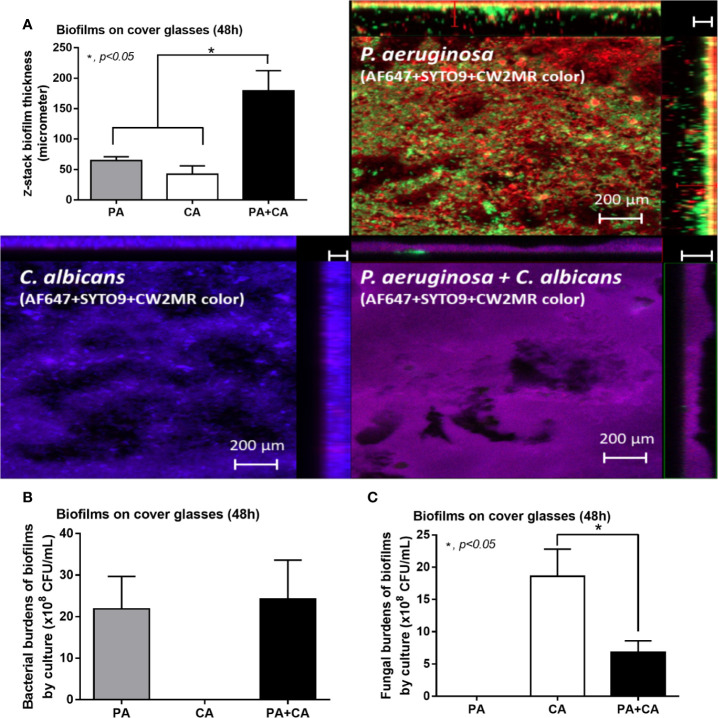

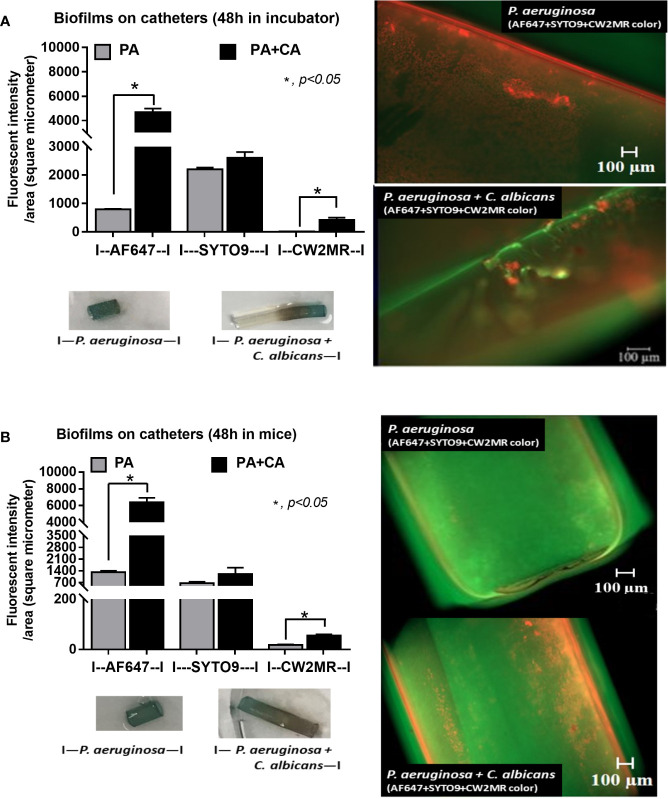

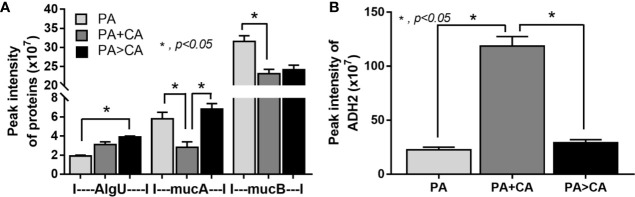

Candida albicans enhanced biofilm production of P. aeruginosa through the induction of alginate-related proteins and was attenuated by l-cysteine, which has been proposed as an interesting anti-biofilm in clinical situations. Crystal violet–stained biofilms were higher in P. aeruginosa plus C. albicans (PA+CA) as early as 48 h post-incubation ( Figure 1B ). Without Candida, P. aeruginosa (PA) produced more biofilms than other bacteria, and most bacteria, except A. baumannii and E. coli, produced more biofilms than C. albicans (CA) ( Figure 1B ). Despite the lower initial bacterial burdens, biofilms of mixed bacteria Candida, except K. pneumoniae, were similar to or higher than biofilms from bacteria alone ( Figure 1C ), implying an additive effect of fungi on biofilm production. Confocal electron microscope examination of PA+CA biofilms on cover glasses demonstrated the highest ECM ( Figures 2A, B ) and thickness (z-stack imaging) ( Figure 3A ) with a similar intensity of bacterial nucleic acid ( Figure 2A ) and bacterial culture ( Figure 3B ) when compared with biofilms from bacteria alone. However, fungal burdens in PA+CA were lower than CA alone ( Figure 3C ), which implies an impact of lower fungal burdens in PA+CA preparation ( Figure 1A ) or antifungal molecules of Pseudomonas (Kerr et al., 1999). For a closer representative of the clinical situation, biofilms were induced in catheters using incubator or subcutaneous implantation. PA+CA induced the highest ECM ( Figures 4A, B ), which is similar to the cover glass biofilms ( Figure 2 ). Of note, there was a trend of higher PA burdens in PA+CA compared with PA alone ( Figures 4A, B ) despite the initially lower number of bacteria.

Figure 2.

Intensity of fluorescent stains from 48 h biofilm on cover glasses of P. aeruginosa alone, Candida alone, and P. aeruginosa + C. albicans (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans) for ECM by AF647 (red color fluorescence), bacterial nucleic acid by SYTO9 (green color fluorescence), and fungal cell wall by calcofluor white (CW2MR; blue color fluorescence) (A) with the representative fluorescent images (B) are demonstrated. There was different depth on biofilms in images of the P. aeruginosa + C. albicans group because of the prominent biofilm thickness. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups (A). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed.) (*p<0.05; # p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Biofilm thickness from 48 h biofilm on cover glasses of P. aeruginosa alone, Candida alone, and P. aeruginosa + C. albicans (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans) as evaluated by z-stack analysis of fluorescent images (A) and the burdens of organisms by culture for bacteria (TSA) and for fungi (SDA) (B, C) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups, (A–C). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed.)

Figure 4.

Diagram of the experimental design demonstrated the lower bacteria during biofilm preparation of P. aeruginosa and C. albicans (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans) compared with P. aeruginosa alone with the score of fluorescent intensity for ECM (AF647), bacterial nucleic acid (SYTO9), and fungal cell wall (CW2MR) together with representative fluorescent images (right side) with eye visualization biofilms (below) of the catheter biofilms after 48 h in an incubator (A) and in mice (B) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by Student’s t-test for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups (A, B). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed for A and n = 5/group for B.)

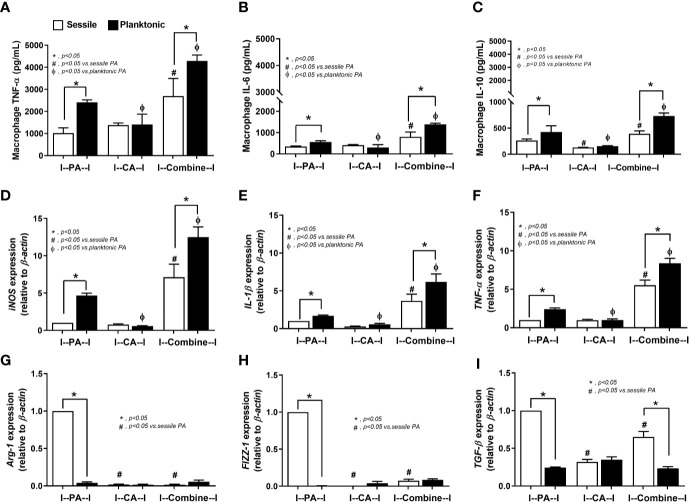

The responses against PA+CA biofilms were tested because the additive effect of Candida on bacterial immune responses was demonstrated in several models (Panpetch et al., 2017; Panpetch et al., 2019). With the planktonic (free-living) form of organisms ( Figure 5 , black columns), PA+CA induced the highest cytokine responses (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10) with the highest expression of genes for pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage polarization (iNOS, IL-1β, and TNF-α) and low expression of genes for anti-inflammatory M2 polarization (Arg-1, FIZZ-1, TGF-β) ( Figures 5A–I ). Planktonic PA induced higher cytokines and expression of M1 polarization genes with similar expression of M2 polarization genes when compared with planktonic CA ( Figures 5A–I ). In sessile (biofilm) form ( Figure 5 , white columns), PA+CA still induced the highest cytokines and gene expression of M1 polarization but in lower levels than the planktonic form ( Figures 5A–F ), which supports compromised antibacterial mechanisms of biofilms (Thurlow et al., 2011; Yamada and Kielian, 2019).

Figure 5.

Characteristics of RAW264.7 cells (macrophages) after 6 h incubation of P. aeruginosa, C. albicans, or P. aeruginosa with C. albicans (combined) in sessile (biofilm) and planktonic form (free-living) as determined by supernatant cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10) (A–C), gene expression of macrophage polarization of M1 (iNOS, IL-1β, TNF-α) and M2 (Arg-1, FIZZ-1, TGF-β) (D–I) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups (A–I). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed.) (*p<0.05; # p<0.05).

Candida on the Pre-Formed Pseudomonas Biofilms Enhances Biofilm Thickness Through Matrix-Protein Induction, a Proteomic Analysis

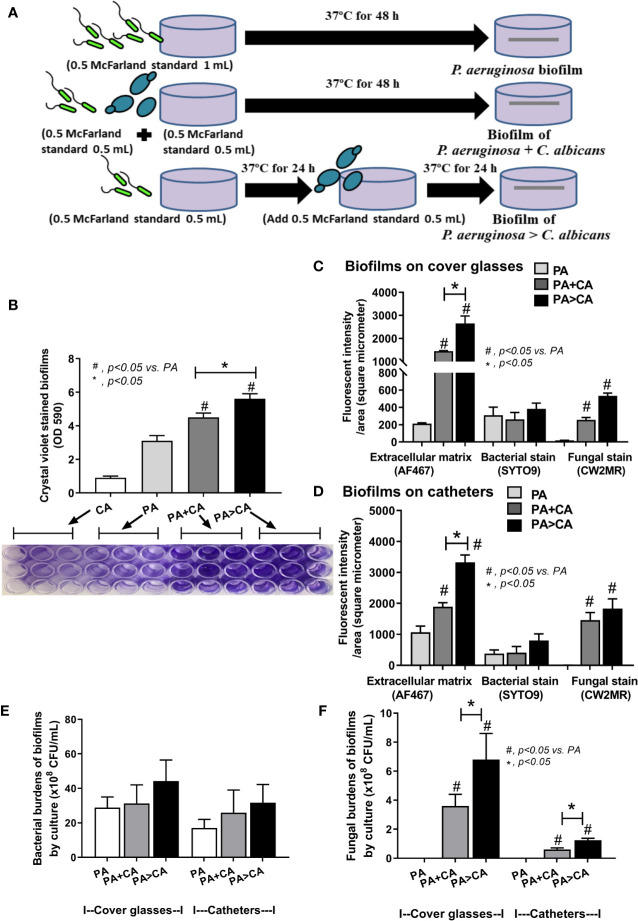

Because gut leakage–induced candidemia could be presented during bacterial sepsis (Amornphimoltham et al., 2019) and catheter-related bacterial sepsis is common (Phua et al., 2019; Reitzel et al., 2019), interaction between Candida and bacterial biofilm is possible. Then, C. albicans were added on Pseudomonas biofilms (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans; PA>CA) in comparison with biofilms that were formed with the initial mixture of organisms (PA+CA) ( Figure 6A ). Accordingly, PA>CA and PA+CA demonstrated higher biofilm formation compared with PA alone by crystal violet staining (96-well plates) ( Figure 6B ). Of note, fungal biofilms of CA alone were much less when compared with other groups in 96-well plate staining ( Figure 6B ), and the fungal biofilms were non-detectable in catheters (data not shown). Biofilms by fluorescent intensity of ECM (AF467) (cover glasses and catheters) were not different in bacterial burdens (SYTO9 stains and culture) ( Figures 6C–E and 7 ) despite the lower initial organisms in the preparation of PA>CA and PA+CA versus PA biofilms ( Figure 6A ). Of note, Candida burdens in PA>CA were higher than PA+CA biofilms by culture ( Figure 6F ) but not by fluorescent staining ( Figures 6C, D ). This is perhaps due to the higher nutrients in the culture system. Nevertheless, these imply the possible differences between biofilm structures of PA>CA versus PA+CA that lead to the proteomic analysis that focuses on Pseudomonas ECM proteins.

Figure 6.

Diagram of the experimental design demonstrated lower bacteria in the biofilm preparation of simultaneous incubation of P. aeruginosa and Candida (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans) or the Candida addition in 24 h biofilm-formed bacteria (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans) in comparison with P. aeruginosa biofilms (A), crystal violet–stained biofilm in 96-well plates with representative pictures (B), fluorescent intensity of ECM by AF647 (red), bacterial nucleic acid by SYTO9 (green), and fungal cell wall by calcofluor white (CW2MR; blue) induced on cover glass biofilms and catheters (in incubator) (C, D) and organism burdens from biofilms using TSA for bacteria (E) and SDA for fungi (F) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups, respectively (B–F). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed.) (*p<0.05; # p<0.05).

Figure 7.

Representative fluorescent images of biofilms induced on cover glasses and catheters (in incubator) (A, B) stained for ECM by AF647 (red), bacterial nucleic acid by SYTO9 (green), and fungal cell wall by calcofluor white (CW2MR; blue) are demonstrated.

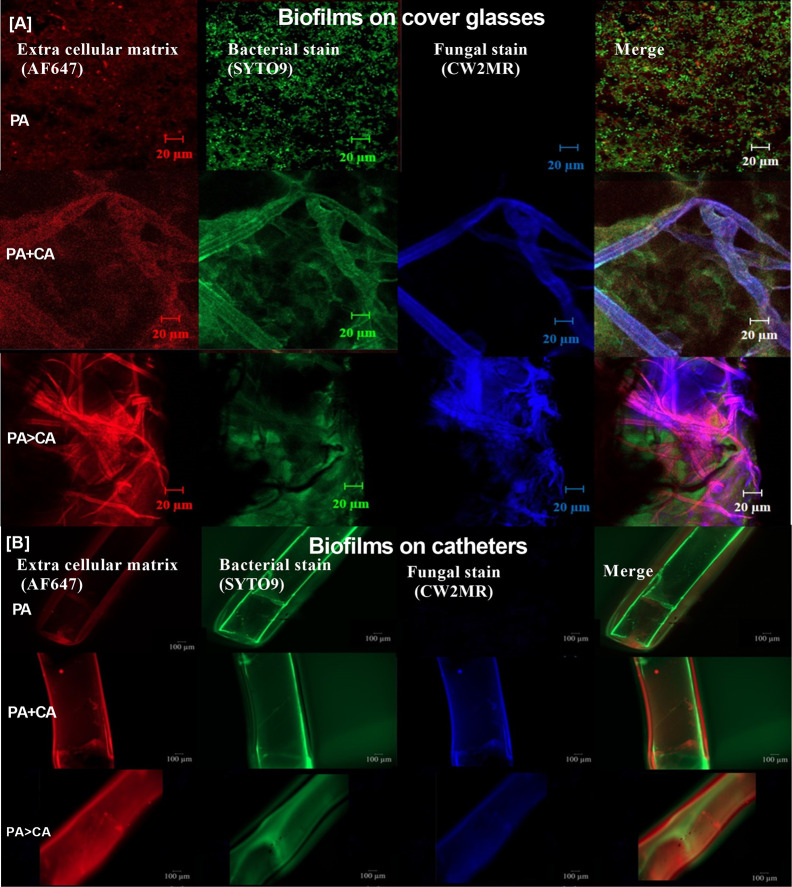

Biofilms were demonstrated in all groups; 591 proteins from proteomic analysis that presented in all groups that are presented in the Venn diagram ( Supplementary Data 1 ) were classified by protein biological process based on the PANTHER classification system (http://www.pantherdb.org) into the following: i) proteins in PA+CA and PA>CA that were higher than PA alone (37 proteins, including RNA polymerase sigma H factor; AlgU), ii) proteins in PA+CA that were higher than PA>CA (19 proteins without ECM proteins), iii) proteins in PA>CA that were higher than PA+CA (81 proteins, including sigma factor AlgU negative regulatory protein; mucA), and iv) proteins in PA+CA and PA>CA that were lower than PA (450 proteins, including negative regulator of the sigma factor AlgU; mucB) ( Supplementary data 1 ). Most of bacterial proteins in PA+CA or PA>CA were lower than PA alone ( Supplementary data 1 ) because of the lower initial bacteria in preparation of mixed-organism biofilms ( Figure 6A ). Indeed, high ECM initiators AlgU and mucA and low ECM inhibitor mucB (Schurr et al., 1996) in PA>CA compared with PA alone or PA+CA ( Figure 8A ) might be responsible for the prominent ECM in the PA>CA group. Of note, cleavage mucA is necessary for alginate production (Damron et al., 2009; Li et al., 2019). Likewise, the intercept proteins with Candida biofilms (CA) ( Supplementary data 2 ) were divided into i) proteins in PA+CA and PA>CA that were higher than PA alone (4 proteins, including ADH2; alcohol dehydrogenase 2), ii) proteins in PA+CA that were higher than PA>CA (19 proteins without ECM proteins), and iii) proteins in PA+CA and PA>CA that were lower than PA (18 proteins without ECM proteins) ( Supplementary data 2 ). Higher ADH2, an ECM restriction protein (Mukherjee et al., 2006), in PA+CA ( Figure 8B ) might be responsible for the lower ECM when compared with the PA>CA group ( Figures 6B–D ).

Figure 8.

Proteomic analysis of biofilms from P. aeruginosa alone (PA) and PA with Candida by simultaneous incubation of Candida together with bacteria (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans; PA+CA) or the Candida addition in 24 h biofilm-formed bacteria (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans; PA>CA) as determined by the peak intensity of proteins in the ECM production process (AlgU, RNA polymerase sigma H factor; mucA, sigma factor AlgU negative regulatory protein; and mucB, negative regulator of the sigma factor AlgU) (A) and those of biofilms from Candida albicans alone (CA) and CA simultaneously incubated together with P. aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans; PA+CA) or the Candida addition in 24 h biofilm-formed bacteria (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans; PA>CA) as determined by the peak intensity of proteins in the ECM production process (ADH2, alcohol dehydrogenase) (B). Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis (A, B). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent duplicate experiments were performed.)

Anti-Biofilms That Interfere With ECM Proteins In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluations

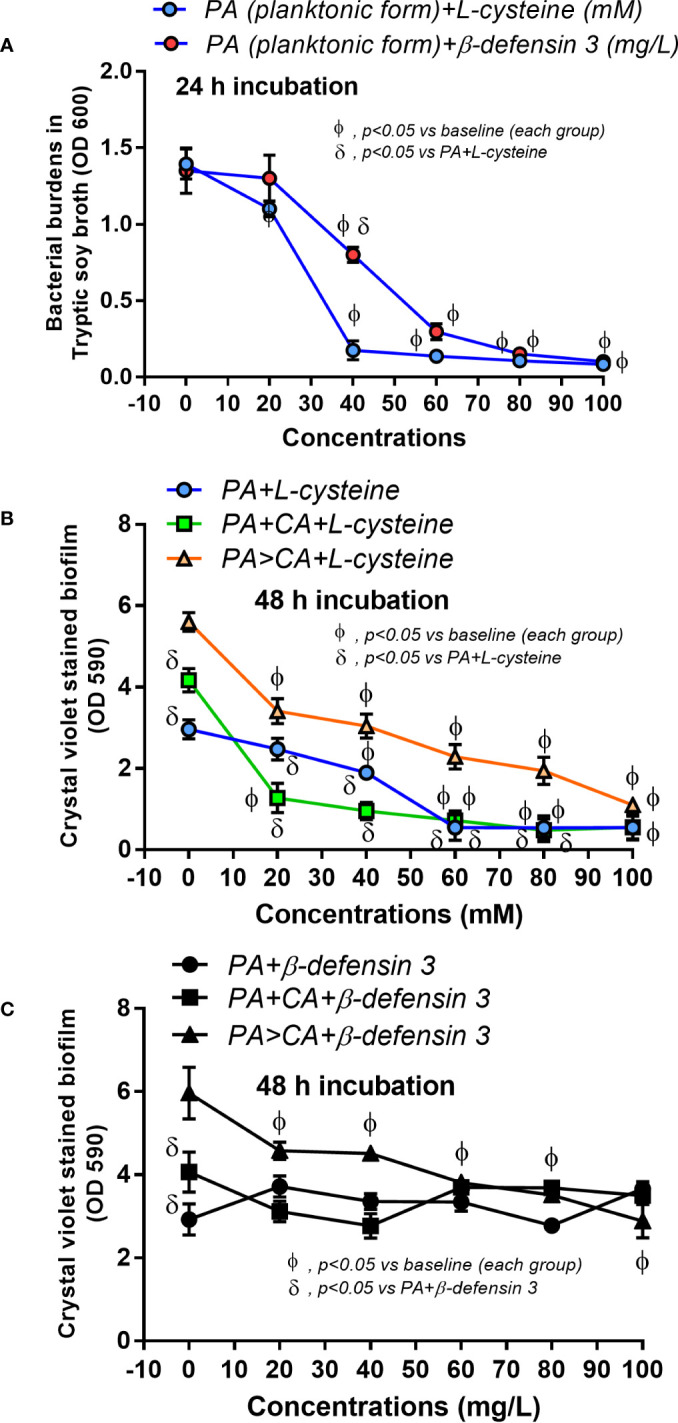

Because i) biofilm ECM of Pseudomonas with Candida were more prominent than biofilms of Pseudomonas alone despite the lower bacteria in the preparation process ( Figures 2 – 4 , 6 , and 7 ) and ii) proteins that accelerate ECM were demonstrated in the PA>CA group by the proteomic analysis ( Figures 8A, B ), anti-biofilms with ECM interference are of strong interest. Accordingly, l-cysteine, which is an ECM-reducing agent, and β-defensin 3, an anti-biofilm with bactericidal activity, reduced both planktonic PA and PA biofilms. However, only l-cysteine attenuated biofilms of PA+CA and PA>CA ( Figures 9A–C ). In addition, l-cysteine reduced gene expression of ECM promoters, including mucA, cysB, and lasR but not psl ( Figures 10A–E ). To test the catheter biofilms in vivo, catheters with biofilms were prepared before subcutaneous implantation in mice ( Figure 11A ). Mice with biofilm catheters from PA>CA or PA+CA demonstrated more severe sepsis as determined by mortality, renal injury, liver damage, bacteremia, and serum cytokines ( Figures 11B–F ) with the higher burdens of Pseudomonas but not fungi in catheter biofilms ( Figure 11G ). Of note, bacterial burdens in cover glass and catheter biofilms (in incubator) were not different among PA, PA+CA, and PA>CA ( Figure 6E ) while bacterial burdens from catheter biofilms (in mice) of PA+CA and PA>CA were higher than PA alone ( Figure 11G ). This is possibly due to the higher organism nutrients in mice compared with the in vitro system.

Figure 9.

Effect of the different concentrations of l-cysteine and β-defensin 3 on bacterial burdens in TSB culture of planktonic P. aeruginosa after 24 h incubation (A) and crystal violet–stained biofilms on 96-well plates after 48 h incubation (B, C) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation. The differences between groups were examined by Student’s t-test (A) and by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis (B, C). The differences between the individual time points versus the baselines were examined by repeated-measures ANOVA analysis (A–C). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed.)

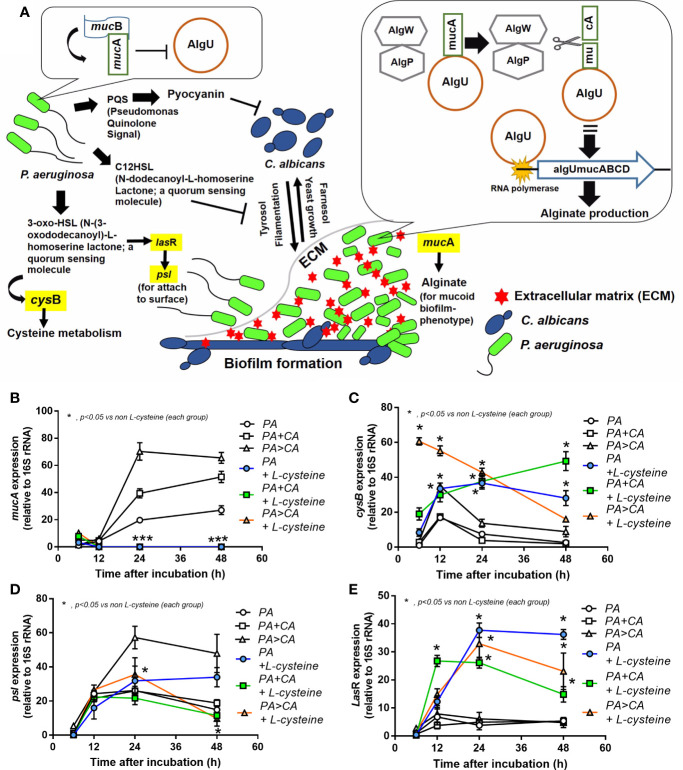

Figure 10.

Diagram of some important genes that regulate ECM protein formation (A) demonstrates i) Pseudomonas produces 3-oxo-HSL and several proteins to initiate biofilms (yellow highlights are selected genes to explore in this study) and secretes pyocyanin and C12-HSL to inhibit Candida growth (Kerr et al., 1999), ii) Candida produces Tyrosol and Farnasol for fungal biofilms (Pierce, 2005; McAlester et al., 2008), iii) bacterial attachment on Candida pseudohyphae on mixed-organism biofilms (Fourie et al., 2016), and iv) biofilm inhibition by mucB in planktonic bacteria (left side) and alginate synthesis by AlgU in sessile bacteria (right side) (Schurr et al., 1996). Additionally, expression of some genes from biofilms of P. aeruginosa alone (PA) and PA with Candida by initially simultaneous incubation (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans) or the Candida addition at 24 h biofilm-formed bacteria (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans) with or without l-cysteine (anti-biofilm) (B–E) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups (B–E). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed.) (*p<0.05; ***p<0.001).

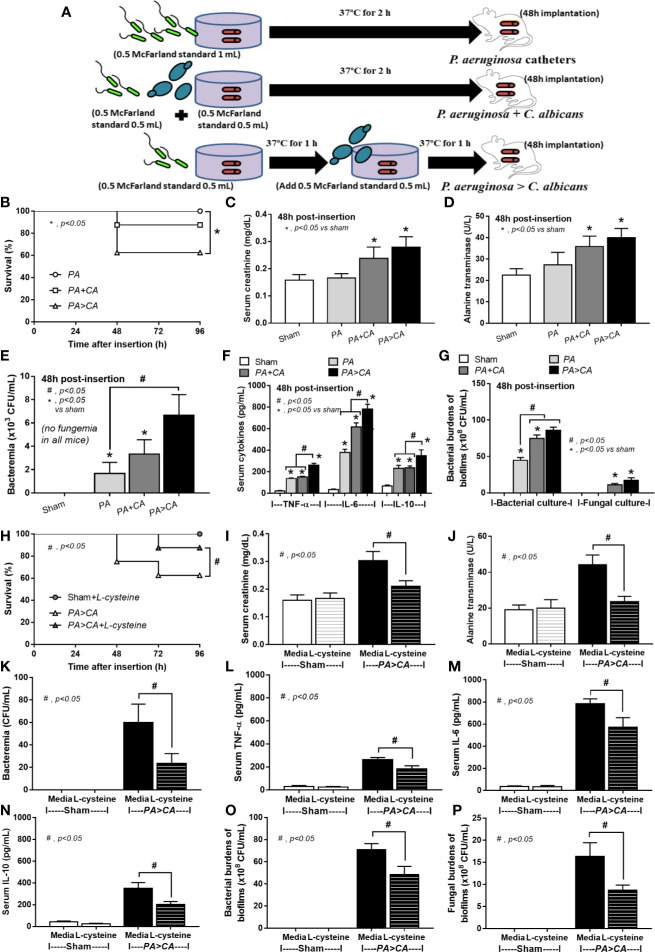

Figure 11.

Diagram of the preparation of catheter biofilms of P. aeruginosa alone (PA) and with Candida by simultaneous incubation of Candida together with bacteria (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans) or the Candida addition in 1.5 h biofilm-formed bacteria (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans) before 48 h of subcutaneous implantation in mice (A) are indicated. Characteristics of the catheter insertion mouse model as determined by survival analysis (B), kidney and liver injury (serum creatinine and alanine transaminase) (C, D), bacteremia (E), serum cytokines (F), and organism burdens of catheter biofilms (G) are demonstrated. Additionally, characteristics of mice with P. aeruginosa > C. albicans biofilm catheters with or without l-cysteine incubation as evaluated by these parameters (H–P) are demonstrated. The survival analysis (B, H) and the differences between groups were examined by Log-rank test and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis, respectively (C–G, I–P). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (n = 12/group for survival analysis and n = 6–8/group for other parameters.)

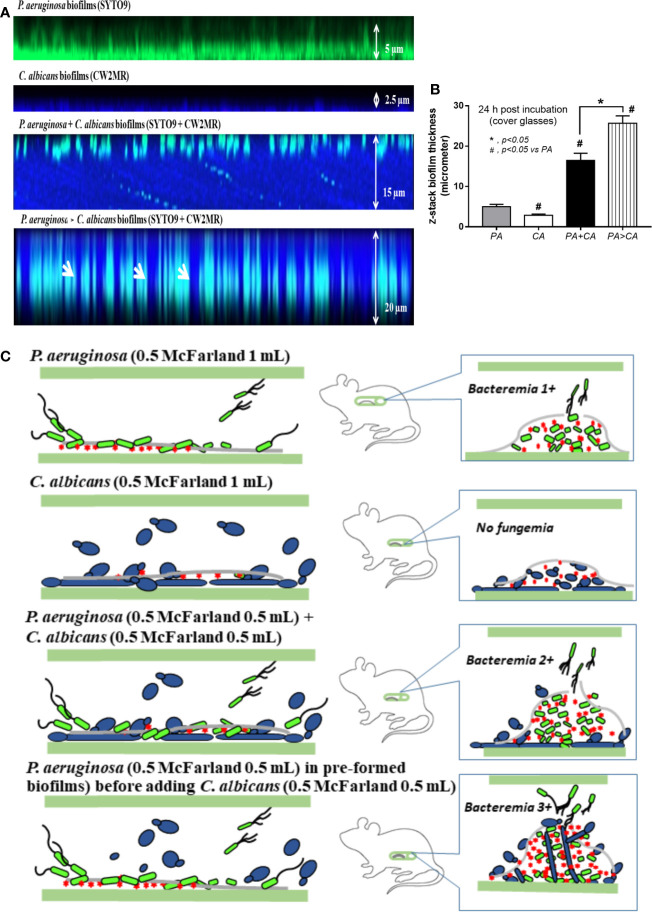

Bacteremia in PA>CA was most severe among all groups ( Figure 11E ), implying the easier detachment of bacteria from the biofilms compared with biofilms of PA alone. Because PA>CA demonstrated the most severe sepsis, biofilm catheters with or without l-cysteine were implanted into this model. As such, l-cysteine attenuated catheter-induced sepsis in the PA>CA group as determined by the previously mentioned sepsis parameters ( Figures 11H–N ) and reduced burdens of both bacteria and fungi in catheter biofilms ( Figures 11O, P ), suggesting an impact of bactericidal and fungicidal properties. In addition, the possible structural difference between PA+CA versus PA>CA biofilms was demonstrated with z-stack lateral view images of 24 h cover glass biofilms. As such, bacteria (green color of SYTO9) were on top of fungi (blue color of CW2MR) in PA+CA biofilms and vice versa on PA>CA with the prominent thickness in PA>CA biofilms ( Figures 12A, B ). The connections of blue color of fungi from the upper to the lower part of biofilms ( Figure 12A , arrows) were possibly penetrating Candida germ-tube onto biofilms that induced bacterial exit-portals and caused easier bacterial dissemination in mice.

Figure 12.

Representative fluorescent z-stack lateral-view images of bacterial nucleic acid by SYTO9 (green) and fungal cell wall by calcofluor white (CW2MR; blue) from biofilms of single (P. aeruginosa or C. albicans) and mixed organisms that initially incubated together and incubated for 24 h (P. aeruginosa + C. albicans) or the Candida addition at 12 h biofilm-formed bacteria (P. aeruginosa > C. albicans) and further incubated for another 12 h on cover glasses (A) is demonstrated (arrows indicate the possible Candida germ tubes that grow from the top into the bottom of biofilms). In addition, thickness of the biofilms (B) and the working hypothesis (left side, catheter during the preparation; right side, the proposed situations in catheter biofilms in vivo) show the enhanced bacterial dissemination in P. aeruginosa > C. albicans biofilms from Candida germ-tube elongation (C) are demonstrated. Mean ± SE was used for data presentation, and the differences between groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis for comparisons of multiple groups or 2 groups (B). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Independent triplicate experiments were performed for A, B.)

Discussion

Although the enhanced Pseudomonas ECM production by the Candida presentation with the initial mixtures of both organisms are demonstrated (DeVault et al., 1990; Chen et al., 2014), the Candida presentation in the pre-formed Pseudomonas biofilms has not been studied. Indeed, adding Candida into pre-formed Pseudomonas bioflms induced a higher biofilm matrix partly through enhanced mucA expression with easier bacteremia when compared with mixed-organism biofilms from simultaneous incubation. In addition, l-cysteine, an anti-biofilm with a matrix inhibitor, attenuated mixed-organism biofilms both in vitro and in vivo.

Bacteremia or candidemia from gut-derived organisms is common (Amornphimoltham et al., 2019) and possibly increases risk of mixed-organism biofilms (Gominet et al., 2017). Although Candida produced less biofilm in most of the selected bacteria, perhaps due to the virulence (Hirota et al., 2017), Candida-enhanced biofilms of most bacteria, especially P. aeruginosa (PA), supported the cross-talk between these species (Fourie et al., 2016). In the intensive care unit, P. aeruginosa overgrowth in intestines (Okuda et al., 2010; Amornphimoltham et al., 2019), antibiotic-increased intestinal C. albicans (CA) (Panpetch et al., 2019), and mixed bacterial-fungal biofilms during sepsis (Pierce, 2005; McAlester et al., 2008) are mentioned. Here, PA+CA biofilms demonstrated prominent burdens of bacteria but not fungi compared with single-organism biofilms despite the lower organisms at preparation, which implies Candida-enhanced bacterial growth. Although immune responses against sessile organisms were lower than the planktonic forms (Yamada and Kielian, 2019), PA+CA in sessile forms induced more inflammatory effect than the sessile form of single organisms, supporting the sysnergistic responses against bacteria with fungi (Panpetch et al., 2017; Panpetch et al., 2019).

Candida on pre-formed Pseudomonas biofilms (PA>CA) induced a higher biofilm matrix than the simultaneous organism incubation (PA+CA) with similar bacterial burdens among PA, PA+CA, and PA>CA. The enhanced Pseudomonas growth in mixed-organism biofilms might, in part, be due to β-glucan, a major fungal cell wall component, as β-glucan mixed in culture media enhanced bacterial growth (Hiengrach et al., 2020) and oral β-glucan administration increased pathogenic bacteria in gut (Charlet et al., 2018). Likewise, mannans on Candida outer surface mediate β-glucosyltransferase binding, improving glucan-matrix production and enhancing bacterial–fungal association (Rodrigues et al., 2020). Although fungal burdens in PA>CA biofilms were higher than PA+CA biofilms, the impact of Candida on matrix production of mixed-organism biofilm was not dominant as Candida burdens of mixed-organism biofilms was lower than CA biofilms ( Figure 3C ). This was possibly due to the Pseudomonas antifungal effect (Kerr et al., 1999; Fourie et al., 2016).

Pseudomonas biofilms consist of at least 3 extracellular polymers, including i) polysaccharide synthesis locus (psl) for the cell attachment; ii) pel, a cationic exopolysaccharide for pellicle forming at the liquid interface; and iii) alginate for the mucoid phenotype that retains water (and nutrients) and provides resistance against antibiotics and host immunity (Lee and Yoon, 2017). Proteomic analysis in PA>CA demonstrated higher AlgU with lower mucB when compared with PA and higher mucA than PA+CA. As such, alteration of AlgU, mucA, and mucB implied the modification on alginate in the PA>CA group. Despite the possible lesser Candida impact on mixed-organism biofilms, ADH2, a biofilm-inhibitory enzyme (Mukherjee et al., 2006), in PA+CA was higher than PA>CA, which could possibly be associated with the lower biofilm matrix in PA+CA. Prominent ECM, but not organism burdens, should be a major component of mixed-organism biofilms; therefore, several genes for ECM synthesis were explored. As such, mucA and psl in PA>CA biofilms were higher than PA+CA and PA alone, and only mucA in PA+CA was higher than PA alone ( Figure 10 ), implying the importance of mucA (anti-sigma factor) in mucoid biofilms of mixed organisms. Although mucA (an anti-sigma factor) binds to AlgU and inhibits its activity, cleavage-mucA provides an important step in matching with AlgU prior to AlgU release for alginate transcription ( Figure 10A ) (Damron et al., 2009; Li et al., 2019), and mucA mutation induces alginate overproduction (Moradali et al., 2017). Perhaps ethanol produced by Candida interferes with mucA gene expression as ethanol induces several molecules from P. aeruginosa, including mucA, exopolysaccharide (pel and psl), and antifungal phenazine [5-methyl phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (5MPCA)] (Chen et al., 2014; Tashiro et al., 2014). In addition, several other stimuli, such as NaCl and harsh environments, alter mucA and enhance biofilm formation (Harty et al., 2019). Hence, Candida presentation is an exacerbation factor of Pseudomonas biofilms, possibly through stress induction on bacteria. More studies on this topic are of interest.

Bacteremia and sepsis severity in mice with mixed-organism biofilms in catheters were more prominent than in mice with PA biofilms despite the initially lower bacteria at preparation ( Figure 11A ). In mixed-organism biofilms, bacterial burdens but not fungi were higher than PA biofilms in vivo ( Figure 11G ), and fungal burdens but not bacteria were higher than PA biofilms in vitro ( Figures 6E, F ). This demonstrated a proliferation ability of P. aeruginosa after Candida stimulation in an environment with less limitation on nutrients than the in vivo situation, which implies a possible complication of candidemia during Pseudomonas sepsis. On the other hand, synergy of Candida on Pseudomonas on biofilm production could be demonstrated both in vivo and in vitro. Because Candida induces Pseudomonas biofilm production, anti-biofilms with direct effect on biofilms are interesting. Here, N-acetyl-l-cysteine (l-cysteine), a thiol-containing cysteine derivative that disrupts disulfide bonds and cysteine utilization (Olofsson et al., 2003; Flemming et al., 2007), reduced ECM production in mixed-organism biofilms. In addition, bactericidal and fungicidal activity of l-cysteine (Olofsson et al., 2003; El-Baky et al., 2014) might also be responsible for reduced organism burdens inside catheters and attenuated septicemia. On the other hand, β-defensin 3, a bactericidal anti-biofilm, could not attenuate mixed-organism biofilms despite similar bactericidal activity with l-cysteine (Maisetta et al., 2006). Additionally, Candida enhanced alginate formation of Pseudomonas. Candida presentation in pre-formed Pseudomonas biofilms induced the thicker biofilms with an easier bacterial dissemination and could be possibly due to a defect on the biofilm surface during Candida germ-tube penetration ( Figure 12C ). Then, candidemia in patients with catheter-induced sepsis from Pseudomonas should be more clinically concerned, and l-cysteine is an interesting strategy against mixed-organism biofilms. However, our model of biofilm production was induced under static conditions. The utilization of a flow-cell system (Kerckhoven et al., 2016) should provide a more realistic condition. Further studies are interesting.

In conclusion, C. albicans on pre-formed Pseudomonas biofilms enhanced Pseudomonas ECM production through increased alginate producing genes, AlgU and mucA, and induced the easier biofilm disintegration that caused organismal dissemination. However, l-cysteine inhibited ECM production of the mixed-organism biofilms that might be useful for biofilm prevention and attenuation of catheter-related sepsis.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD020949.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by Thailand Government Fund (RSA-6080023), Thailand Research Fund (RES_61_202_30_022) and Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund 2017 (76001-HR). PP was supported by Second Century Fund (C2F) for Postdoctoral Fellowship, Chulalongkorn University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2020.594336/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alexandraki I., Palacio C. (2010). Gram-negative versus Gram-positive bacteremia: what is more alarmin(g)? Crit. Care 14, 161. 10.1186/cc9013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almirante B., Rodriguez D., Park B. J., Cuenca-Estrella M., Planes A. M., Almela M., et al. (2005). Epidemiology and predictors of mortality in cases of Candida bloodstream infection: results from population-based surveillance, barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 1829–1835. 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1829-1835.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amornphimoltham P., Yuen P. S. T., Star R. A., Leelahavanichkul A. (2019). Gut leakage of fungal-derived inflammatory mediators: part of a gut-liver-kidney axis in bacterial sepsis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 64, 2416–2428. 10.1007/s10620-019-05581-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam S., Darouiche R. O. (2011). Role of antibiofilm-antimicrobial agents in controlling device-related infections. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 34, 752–758. 10.5301/ijao.5000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batoni G., Maisetta G., Esin S. (2016). Antimicrobial peptides and their interaction with biofilms of medically relevant bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858, 1044–1060. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouza E., Burillo A., Munoz P., Guinea J., Marin M., Rodriguez-Creixems M. (2013. a). Mixed bloodstream infections involving bacteria and Candida spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 1881–1888. 10.1093/jac/dkt099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouza E., Eworo A., Fernandez Cruz A., Reigadas E., Rodriguez-Creixems M., Munoz P. (2013. b). Catheter-related bloodstream infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria. J. Hosp. Infect. 85, 316–320. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buret A., Ward K. H., Olson M. E., Costerton J. W. (1991). An in vivo model to study the pathobiology of infectious biofilms on biomaterial surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 25, 865–874. 10.1002/jbm.820250706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlet R., Bortolus C., Barbet M., Sendid B., Jawhara S. (2018). A decrease in anaerobic bacteria promotes Candida glabrata overgrowth while beta-glucan treatment restores the gut microbiota and attenuates colitis. Gut. Pathog. 10, 50. 10.1186/s13099-018-0277-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wen Y. M. (2011). The role of bacterial biofilm in persistent infections and control strategies. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 3, 66–73. 10.4248/IJOS11022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., II, Dolben E. F., Okegbe C., Harty C. E., Golub Y., Thao S., et al. (2014). Candida albicans ethanol stimulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa WspR-controlled biofilm formation as part of a cyclic relationship involving phenazines. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004480. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damron F. H., Qiu D., Yu H. D. (2009). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensor kinase KinB negatively controls alginate production through AlgW-dependent MucA proteolysis. J. Bacteriol. 191, 2285–2295. 10.1128/JB.01490-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darouiche R. O. (2002). Composition and methods for preventing and removing biofilm embedded microorganisms from the surface of medical devices (Houston, TX: U.S; ). U.S. Patent No 6,475,434 B1

- de Kievit T. R. (2009). Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 279–288. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVault J. D., Kimbara K., Chakrabarty A. M. (1990). Pulmonary dehydration and infection in cystic fibrosis: evidence that ethanol activates alginate gene expression and induction of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Mol. Microbiol. 4, 737–745. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00644.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhamgaye S., Qu Y., Peleg A. Y. (2016). Polymicrobial infections involving clinically relevant gram-negative bacteria and fungi. Cell Microbiol. 18, 1716–1722. 10.1111/cmi.12674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Azizi M. A., Starks S. E., Khardori N. (2004). Interactions of Candida albicans with other Candida spp. and bacteria in the biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96, 1067–1073. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Baky R. M. A., Sakhy M., Gad G. F. M. (2014). Antibiotic susceptibility pattern and genotyping of Campylobacter species isolated from children suffering from gastroenteritis. Ind. J. Med. Microbiol. 32, 240–246. 10.4103/0255-0857.136550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming H. C., Neu T. R., Wozniak D. J. (2007). The EPS matrix: the house of biofilm cells. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7945–7947. 10.1128/JB.00858-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming H. C., Wingender J., Szewzyk U., Steinberg P., Rice S. A., Kjelleberg S. (2016). Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 563–575. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourie R., Ells R., Swart C. W., Sebolai O. M., Albertyn J., Pohl C. H. (2016). Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa interaction, with focus on the role of eicosanoids. Front. Physiol. 7, 1–15. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafoor A., Hay I. D., Rehm B. H. (2011). Role of exopolysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and architecture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 5238–5246. 10.1128/AEM.00637-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gominet M., Compain F., Beloin C., Lebeaux D. (2017). Central venous catheters and biofilms: where do we stand in 2017? APMIS 125, 365–375. 10.1111/apm.12665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn J. S., Bakaletz L. O., Wozniak D. J. (2016). What’s on the outside matters: the role of the extracellular polymeric substance of gram-negative biofilms in evading host immunity and as a target for therapeutic intervention. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 12538–12546. 10.1074/jbc.R115.707547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harty C. E., Martins D., Doing G., Mould D. L., Clay M. E., Occhipinti P., et al. (2019). Ethanol stimulates trehalose production through a SpoT-DksA-AlgU-dependent pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Bacteriol. 201, e00794–e00718. 10.1128/JB.00794-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiengrach P., Panpetch W., Worasilchai N., Chindamporn A., Tumwasorn S., Jaroonwitchawan T., et al. (2020). Administration of Candida albicans to dextran sulfate solution treated mice causes intestinal dysbiosis, emergence and dissemination of intestinal Pseudomonas aeruginosa and lethal sepsis. Shock 53, 189–198. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K., Yumoto H., Sapaar B., Matsuo T., Ichikawa T., Miyake Y. (2017). Pathogenic factors in Candida biofilm-related infectious diseases. J. Appl. Microbiol. 122, 321–330. 10.1111/jam.13330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. A., Sattenapally N., Parikh H., II, Li W., Rumbaugh K. P., German N. A. (2020). Design, synthesis, and evaluation of compounds capable of reducing Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 185, 1–10. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerckhoven M. V., Hotterbeekx A., Lanckacker E., Moons P., Lammens C., Kerstens M., et al. (2016). Characterizing the in vitro biofilm phenotype of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from central venous catheters. J. Microbiol. Methods 127, 95–101. 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. R., Taylor G. W., Rutman A., Hoiby N., Cole P. J., Wilson R. (1999). Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin and 1-hydroxyphenazine inhibit fungal growth. J. Clin. Pathol. 52, 385–387. 10.1136/jcp.52.5.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Yoon S. S. (2017). Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm, a programmed bacterial life for fitness. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 1053–1064. 10.4014/jmb.1611.11056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelahavanichkul A., Worasilchai N., Wannalerdsakun S., Jutivorakool K., Somparn P., Issara-Amphorn J., et al. (2016). Gastrointestinal leakage detected by Serum (1–>3)-β-d-glucan in mouse models and a pilot study in patients with sepsis. Shock 46, 506–518. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. S., Chen Y. C., Kuo S. F., Chen F. J., Lee C. H. (2018). The impact of biofilm formation on the persistence of candidemia. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1196. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Lou X., Xu Y., Teng X., Liu R., Zhang Q., et al. (2019). Structural basis for the recognition of MucA by MucB and AlgU in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . FEBS J. 286, 4982–4994. 10.1111/febs.14995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisetta G., Batoni G., Esin S., Florio W., Bottai D., Favilli F., et al. (2006). In vitro bactericidal activity of human β-defensin 3 against multidrug-resistant nosocomial strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 806–809. 10.1128/AAC.50.2.806-809.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlester G., O’Gara F., Morrissey J. P. (2008). Signal-mediated interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans . J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 563–569. 10.1099/jmm.0.47705-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mear J., Kipnis E., Faure E., Dessein R., Schurtz G., Faure K., et al. (2013). Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions: more than an opportunistic criminal association? Med. Mal. Infect. 43, 146–151. 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradali M. F., Ghods S., Rehm B. H. (2017). Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lifestyle: A paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 7, 1–29. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P. K., Mohamed S., Chandra J., Kuhn D., Liu S., Antar O. S., et al. (2006). Alcohol dehydrogenase restricts the ability of the pathogen Candida albicans to form a biofilm on catheter surfaces through an ethanol-based mechanism. Infect. Immun. 74, 3804–3816. 10.1128/IAI.00161-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga R., Miller J. M., Donlan R. M. (2001). Biofilm formation by gram-negative bacteria on central venous catheter connectors: effect of conditioning films in a laboratory model. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 2294–2297. 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2294-2297.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda J., Hayashi N., Okamoto M., Sawada S., Minagawa S., Yano Y., et al. (2010). Translocation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the intestinal tract is mediated by the binding of ExoS to an Na,K-ATPase regulator, FXYD3. Infect. Immun. 78, 4511–4522. 10.1128/IAI.00428-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson A. C., Hermansson M., Elwing H. (2003). N-acetyl-l-cysteine affects growth, extracellular polysaccharide production, and bacterial biofilm formation on solid surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 4814–4822. 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4814-4822.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole A., Ricker E. B., Nuxoll E. (2015). Thermal mitigation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Biofouling 31, 665–675. 10.1080/08927014.2015.1083985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panpetch W., Somboonna N., Bulan D. E., Issara-Amphorn J., Finkelman M., Worasilchai N., et al. (2017). Oral administration of live- or heat-killed Candida albicans worsened cecal ligation and puncture sepsis in a murine model possibly due to an increased serum (1–>3)-β-d-glucan. PLoS One 12, e0181439. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panpetch W., Somboonna N., Palasuk M., Hiengrach P., Finkelman M., Tumwasorn S., et al. (2019). Oral Candida administration in a Clostridium difficile mouse model worsens disease severity but is attenuated by Bifidobacterium . PLoS One 14, e0210798. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phua A., II, Hon K. Y., Holt A., O’Callaghan M., Bihari S. (2019). Candida catheter-related bloodstream infection in patients on home parenteral nutrition-Rates, risk factors, outcomes, and management. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 31, 1–9. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce G. E. (2005). Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans, and device-related nosocomial infections: implications, trends, and potential approaches for control. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32, 309–318. 10.1007/s10295-005-0225-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasamiravaka T., Labtani Q., Duez P., El Jaziri M. (2015). The formation of biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a review of the natural and synthetic compounds interfering with control mechanisms. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 1–17. 10.1155/2015/759348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel R. A., Rosenblatt J., Chaftari A. M., Raad I., I. (2019). Epidemiology of infectious and noninfectious catheter complications in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JPEN. J. Parenter. Enteral. Nutr. 43, 832–851. 10.1002/jpen.1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricicova M., Kucharikova S., Tournu H., Hendrix J., Bujdakova H., Van Eldere J., et al. (2010). Candida albicans biofilm formation in a new in vivo rat model. Microbiology 156, 909–919. 10.1099/mic.0.033530-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. E., Gomes F., Rodrigues C. F. (2020). Candida spp./Bacteria Mixed Biofilms. J. Fungi. 6, 1–29. 10.3390/jof6010005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr M. J., Yu H., Martinez-Salazar J. M., Boucher J. C., Deretic V. (1996). Control of AlgU, a member of the σE-like family of stress sigma factors, by the negative regulators MucA and MucB and Pseudomonas aeruginosa conversion to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 178, 4997–5004. 10.1128/JB.178.16.4997-5004.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrour H., Ferrer-Espada R., Dandache I., Barcena-Varela S., Sanchez-Gomez S., Chokr A., et al. (2019). AMPs as anti-biofilm agents for human therapy and prophylaxis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1117, 257–279. 10.1007/978-981-13-3588-4_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. H., Kee S. J., Shin M. G., Kim S. H., Shin D. H., Lee S. K., et al. (2002). Biofilm production by isolates of Candida species recovered from nonneutropenic patients: comparison of bloodstream isolates with isolates from other sources. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 1244–1248. 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1244-1248.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro Y., Inagaki A., Ono K., Inaba T., Yawata Y., Uchiyama H., et al. (2014). Low concentrations of ethanol stimulate biofilm and pellicle formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 78, 178–181. 10.1080/09168451.2014.877828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurlow L. R., Hanke M. L., Fritz T., Angle A., Aldrich A., Williams S. H., et al. (2011). Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo . J. Immunol. 186, 6585–6596. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku M., Roschitzki B., Riedel K., Eberl L. (2012). Identification of proteins associated with the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm extracellular matrix. J. Proteome Res. 11, 4906–4915. 10.1021/pr300395j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbarello M., Fiori B., Trecarichi E. M., Posteraro P., Losito A. R., De Luca A., et al. (2012). Risk factors and outcomes of candidemia caused by biofilm-forming isolates in a tertiary care hospital. PloS One 7, e33705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Moser C., Wang H. Z., Hoiby N., Song Z. J. (2015). Strategies for combating bacterial biofilm infections. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 7, 1–7. 10.1038/ijos.2014.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K. J., Kielian T. (2019). Biofilm-leukocyte cross-talk: impact on immune polarization and immunometabolism. J. Innate Immun. 11, 280–288. 10.1159/000492680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Liu Y., Wu H., Hoiby N., Molin S., Song Z. J. (2011). Current understanding of multi-species biofilms. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 3, 74–81. 10.4248/IJOS11027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J. X., Lin Z. W., Chen C., Chen Z., Lin F. J., Wu Y., et al. (2018). Biofilm Formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia strains was found to be associated with CC23 and the presence of wcaG. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8, 21. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD020949.