Abstract

Uveal melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignant tumor in adults. Approximately 50% of patients develop metastatic disease of which greater than 90% of patients develop hepatic metastases. Following the development of liver tumors, overall survival is dismal with hepatic failure being the cause of death in nearly all cases. To prolong survival for patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, controlling the growth of hepatic tumors is essential. This article will discuss imaging surveillance following the diagnosis of primary uveal melanoma; locoregional therapies used to control the growth of hepatic metastases including chemoembolization, immunoembolization, radioembolization, percutaneous hepatic perfusion, and thermal ablation; as well as currently available systemic treatment options for metastatic uveal melanoma.

Keywords: uveal melanoma, chemoembolization, immunoembolization, radioembolization, percutaneous hepatic perfusion

Uveal melanoma, albeit rare, is the most common primary intraocular malignant tumor in adults with an annual incidence of 5.2 per million population. 1 Men have a higher age-adjusted incidence compared with women with 6.0 per million population versus 4.5 per million population, respectively. 1 The median age at the time of diagnosis is 62 years, with a peak age range of 70 to 79 years. 1 The majority of uveal melanoma tumors occur in the Caucasian population (98%) with rare cases detected in other races and ethnicities. 1

Risk factors for developing uveal melanoma include fair skin; light eye color; inability to tan; oculodermal melanocytosis; cutaneous, iris, or choroidal nevi; and the presence of germline BRCA 1-associated protein 1 (BAP1) mutations. 2 Environmental factors such as sunlight exposure have not been unequivocally implicated as a risk factor for developing uveal melanoma. 2

Uveal melanoma develops from melanocytes located within the uveal tract with cases arising from the choroid (90%), ciliary body (6%), and iris (4%). 2 Uveal melanomas are often found incidentally on ophthalmologic examination, but patients may also experience symptoms such as blurred vision, photopsia, metamorphopsia, floaters, and visual field defects. 2 The most common treatment for uveal melanoma is plaque radiotherapy achieving tumor control in more than 92% of cases. 2 Enucleation is recommended for larger diameter and thicker tumors, extraocular extension, and patients with poor visual acuity or pain at presentation. 3

At the time of primary eye tumor diagnosis, metastatic disease is detected in less than 2% of patients. 4 However, metastatic disease develops in up to 50% of patients despite successful treatment of the primary eye tumor. Metastasis occurs via hematogenous spread and most commonly develops within 5 to 10 years and up to 35 years following treatment of the primary eye tumor. 4 The delay in manifestation of metastatic disease years after the diagnosis of the primary uveal melanoma remains unclear. However, circulating tumor cells have been detected within peripheral blood samples of patients without discernable metastases on diagnostic imaging, suggesting that melanoma cells are released into the systemic circulation early and, probably in all cases, prior to the diagnosis and treatment of the primary eye tumor. 4

Specific clinical, cytogenetic, and transcriptomic uveal melanoma features have been associated with a high risk of metastatic spread. Clinical features indicative of increased metastatic risk include advanced age at presentation, male gender, ciliary body tumors, larger diameter and thicker tumors, the presence of subretinal fluid, intraocular hemorrhage, and extraocular tumor extension. 2 Cytogenetic alterations, including monosomy 3 and 8q amplification, are associated with an increased metastatic risk and a poor prognosis. 5 6 7 Monosomy 3 is detected in 65% of uveal melanoma tumors and is associated with a 5-year survival of 37%. 5 Alternatively, a 5-year survival of 90% is seen with tumors lacking chromosomal 3 alterations. 5 Furthermore, patients with tumors demonstrating more than one amplification of 8q have a 5-year survival of 29% and those without 8q amplification have a 5-year survival of 93%. 5 The presence of both monosomy 3 and 8q amplification is associated with a particular poor prognosis. Gene-expression profiling has emerged as an important prognostic indicator of metastatic risk proving to be more accurate than the previously described clinical factors or cytogenetic alterations. Castle Biosciences (Friendswood, TX) has developed a commercially available 15-gene expression profile that divides primary uveal melanoma tumors into two classes: Class 1, low risk of metastatic disease, and Class 2, high risk of metastatic disease. 8 9 Class 1 tumors are further subdivided into 1a and 1b. The 5-year risk of metastatic disease is 2, 21, and 72% for patients with Class 1a, Class 1b, and Class 2 diseases, respectively. 6 To further refine this assessment, the process has been modified to employ a 12-gene expression profiling assay along with the analysis of PRAME mRNA expression. Class 1 PRAME − tumors, Class 1 PRAME + tumors, and Class 2 tumors have a reported metastatic risk of 0, 38, and 71%, respectively. 10

For patients who develop metastases, the liver is the predominant organ of involvement in more than 90% of cases and the liver remains the only site of metastatic disease in approximately 50% of patients. Unfortunately, less than 10% of patients with liver metastases are eligible for surgical resection due to multiplicity of tumors at the time of presentation. A patient's clinical prognosis following the development of metastatic disease is dependent on the ability to control the growth of liver tumors. Historically, prior to the advent of liver-directed therapies, survival for patients with hepatic metastases ranged between 2 and 9 months. 11 12 More recently, locoregional therapies, such as chemo-, immuno-, and radioembolization; percutaneous hepatic perfusion (PHP); and thermal ablation, have been successfully used to control the growth of liver tumors, thereby prolonging survival for patients with uveal melanoma hepatic metastases.

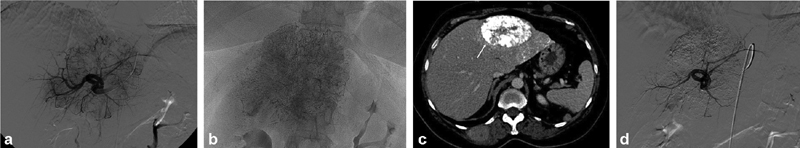

Chemoembolization

Although systemic chemotherapy is ineffective for the treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma, chemoembolization has been touted as an effective treatment for uveal melanoma hepatic metastasis for more than 30 years. 13 Several different chemotherapeutic agents have been employed to treat uveal melanoma hepatic metastases and there is no standard of care or comparative clinical trials to show the benefit of one drug over the other. In 1988, Mavligit et al treated 30 patients with chemoembolization using cisplatin and achieved an overall response rate of 46% and a median survival of 11 months. 14 Not unexpectedly, a longer median survival was found for patients who responded to treatment compared with those who were nonresponders: 14 versus 6 months, respectively. Over the past couple of decades, other researchers have reported median survivals ranging between 6.7 and 21.0 months using cisplatin alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. 15 16 17 However, our institution failed to reproduce similar chemoembolization results using cisplatin achieving a median survival of only 6.6 months and a 0% response rate. 18 Therefore, we have abandoned the use of this chemotherapeutic drug for chemoembolization of uveal melanoma hepatic metastases. Instead, the chemotherapy agent of choice for chemoembolization is 1,3-bis (2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU). Unlike most chemotherapeutics used for chemoembolization, BCNU is a lipophilic agent that is easily dissolved in ethiodized oil. During chemoembolization, the BCNU and ethiodized oil solution become trapped within hepatic tumors due to their increased vascularity compared with normal liver parenchyma. In addition, Kupffer cells, which are responsible for phagocytizing ethiodized oil within normal liver parenchyma, are absent in hepatic tumors, allowing for potentially higher and sustained concentrations of BCNU within treated metastases ( Fig. 1a–d ). 19 Therefore, it is hypothesized that BCNU chemoembolization is superior to chemoembolization using water-soluble agents, which fail to mix well with ethiodized oil. In a phase II chemoembolization trial using 100 mg of BCNU to treat uveal melanoma hepatic metastases in 30 patients, a median survival of 5.2 months (range: 0.1–27.6 months) was achieved. 20 The short median survival in this trial was attributed to the inclusion of patients who did not complete treatment of all hepatic metastases due to rapid progression within the untreated lobe. Exclusion of these patients increased the median survival to 7.4 months (range: 1.6–27.6 months). Moreover, those who responded to treatment had a considerably longer median survival (21.9 months; range: 7.4–27.6 months) compared with those with stable disease (8.7 months; range: 2.9–14.4 months). Not unexpectedly, patients who demonstrated disease progression had a shorter median survival of 3.3 months (range: 1.6–5.6 months). Survival benefit and response rates also correlated positively with tumor burden at the time of initial treatment. For patients with tumor burden less than 20%, the median survival was 19.0 months (range: 3.8–27.8 months) with a response rate of 33%. For patients with 20 to 50% and greater than 50% tumor burdens, the median survivals were 5.6 months (range: 0.1–14 months) and 2.1 months (range: 0.6–7.5 months), respectively, and the response rate for patients with tumor burden greater than 20% was 16.7%.

Fig. 1.

( a ) Left hepatic arteriography demonstrates a large hypervascular tumor in the left lobe of the liver. ( b ) Dense uptake of ethiodized oil following BCNU chemoembolization. ( c ) CT of the abdomen 3 weeks following BCNU chemoembolization demonstrates dense uptake of ethiodized oil within a treated left lobe tumor (arrow). ( d ) Repeat arteriography demonstrates significant decrease in tumor vascularity following chemoembolization. BCNU, 1,3-bis (2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea.

In the same study, two patients with greater than 50% tumor burden at presentation had tumor regression following BCNU chemoembolization. In 2015, we published our experience treating 50 treatment-naive patients presenting with more than 50% hepatic tumor burden with chemoembolization using 200 mg of BCNU. 21 Following chemoembolization, three patients achieved a partial response, 33 patients had stable disease, and 12 patients developed disease progression. The median survival was 7.1 months (range: 1.2–32.3 months) and the median progression-free survival was 5.0 months (range: 1.1–32.3 months). Eleven patients (22%) survived longer than 12 months (range: 12.2–32.3 months) following BCNU chemoembolization with one patient alive at follow-up. Toxicities were also limited and included Grade 3 thrombocytopenia in two patients and asymptomatic grade 4 transaminitis in 13 patients following 16 chemoembolization treatments. Based on these results, BCNU chemoembolization should be considered for patients presenting with bulky uveal melanoma hepatic metastases who possess both adequate renal and hepatic function.

At our institution, we typically reserve BCNU chemoembolization for patients who progress following immuno- and radioembolization or for patients who present with more than 50% replacement of normal liver parenchyma by metastatic disease.

Drug-Eluting Beads

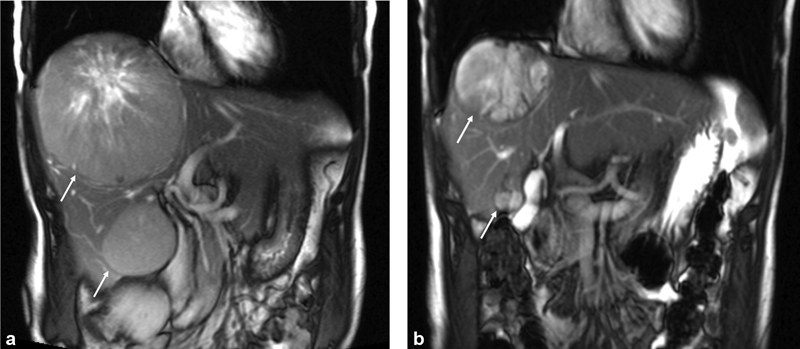

In a retrospective review, the authors found that drug-eluting beads loaded with doxorubicin can be useful in the treatment of large, well-circumscribed liver metastases. 22 Patients are typically treated with up to 4 mL of 100 to 300 μm LC Beads (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) loaded with 150 mg of doxorubicin per lobe to a point of slow antegrade arterial flow. Early in our experience, administration of drug-eluting beads to a point of arterial stasis predisposed patients to biloma formation and prolonged symptoms of postembolization syndrome. Subsequently, it has been our practice to administer steroids intra-arterially prior to the delivery of drug-eluting beads to decrease inflammation and the risk of bile duct injury. Drug-eluting bead treatments are usually followed with BCNU chemoembolization ( Fig. 2a, b ). Between 2011 and 2014, a total of 18 patients presenting with large, nodular tumors were initially treated using drug-eluting beads followed by BCNU chemoembolization achieving a median survival of 18.2 months; three patients survived more than 7 years. Patients often experience a more significant postembolization syndrome following administration of drug-eluting beads than commonly seen with BCNU chemoembolization. While others have published favorable experiences using drug-eluting beads loaded with irinotecan, we were unable to duplicate similar results. 23 24

Fig. 2.

( a ) Contrast-enhanced coronal abdominal MRI of a patient with bulky hepatic tumors (arrows) presenting with fatigue, abdominal distention, pain, and weight loss. ( b ) Contrast-enhanced abdominal MRI following DEBDOX and BCNU chemoembolization demonstrates a decrease in size of both tumors (arrows) following treatment. Patient survived 48 months following initiation of liver-directed therapy and died due to progression of extrahepatic disease.

Percutaneous Hepatic Perfusion

Percutaneous hepatic perfusion involves treatment using a high, weight-based, dose of melphalan infused via the hepatic arteries. The inferior vena cava is occluded using a double-balloon catheter placed through a common femoral vein. Outflow of blood from the hepatic veins is redirected through this double-balloon catheter into a filter system (Delcath Systems, Inc; Queensbury, NY) which extracts the melphalan to avoid systemic circulation of chemotherapy, allowing blood return through a jugular vein sheath. These procedures are performed using general anesthesia, along with a perfusionist to manage the veno-veno bypass. Patients experience a dramatic, acute drop in blood pressure shortly after inclusion of the filters in the circuit, despite aggressive vasopressor support.

As a result of a phase III trial, this procedure was CE Marked in 2012 which allowed sale of the product in the European Economic Area. However, the device was not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 25 In continued pursuit of FDA approval, enrollment of 80 patients in the FOCUS trial (NCT02678572) was completed in January 2020. The system uses a new-generation filter to increase the removal of melphalan designed to reduce systemic complications such as bone marrow suppression.

A retrospective review combining patients from two centers experienced in performing this procedure describes 51 patients treated between 2008 and 2016. 26 A favorable 82.4% tumor control rate (complete response + partial response + stable disease) was reported. However, the hepatic progression-free survival was 9.1 months. The 1-year survival was 64.6%, with a median survival of 15.3 months. Grade 3–4 cardiovascular or coagulopathic toxicities occurred in 37.5% of patients. Transfusions were commonly required in the immediate postprocedure period, and 31.4% of patients experienced at least one episode of grade 3 neutropenia with four documented episodes of neutropenic sepsis.

Another single-institution retrospective study of 16 patients who were treated using the new filter system reports a 93% tumor control rate. 27 One patient who experienced an intraprocedural cardiac arrest was excluded from analysis. The progression-free survival was 11.1 months, with a median survival of 27.4 months. Based on the number of procedures, the rates of grade 3–4 leukopenia and thrombocytopenia were 14% each.

PHP often produces tumor control, but there are inherent and specific risks to this involved procedure, and survival is similar to other liver-directed treatments.

Immunoembolization

Embolization results in tumor ischemia which may control metastases in the liver and provide tumor antigens to the local immune system. Concurrent administration of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), a biological response modifier, induces an inflammatory response in the tumor and surrounding tissue potentially improving antigen presentation to the local immune system. This local stimulation may generate a systemic immune response against tumor cells which may suppress growth of untreated tumors, potentially creating an in situ tumor vaccine. Immunoembolization was initially pursued because patients with liver metastases controlled by chemoembolization often developed extrahepatic disease.

Beginning in 2000, we conducted a dose-escalation Phase I trial to investigate the safety of treating patients with immunoembolization. 28 Thirty-four patients with less than 50% hepatic tumor burden were included in the trial. Patients underwent immunoembolization at 4-week intervals with GM-CSF (25–2,000 μg) emulsified in ethiodized oil, followed by gelatin sponge embolization to a point of near-arterial stasis. Abdominal MRI and CT were performed after every two treatments to evaluate for tumor response and extrahepatic disease. The primary endpoints were dose-limiting toxicity and maximum tolerated dose. Thirty-two percent of patients had a complete or partial response, and another 32% had stable disease. The median survival was 14.4 and 33.7 months for those who responded, with a 1-year survival of 62%. Treatments were well tolerated with symptoms of mild postembolization syndrome. A maximum tolerated dose was not determined.

Patients treated with ≥1,500 μg GM-CSF had a significant delay in progression of extrahepatic metastases compared with those treated with a lower dose of GM-CSF. 26 When compared with a similar group of patients treated with BCNU chemoembolization, those treated with higher GM-CSF doses had a significant increase in median survival (20.4 months) and a delay in progression of extrahepatic metastases (median: 12.4 months). 29 There was no significant difference in overall or progression-free survival between patients who received BCNU chemoembolization and lower doses of GM-CSF. Therefore, stabilization of hepatic metastases was most likely achieved by the ischemic effects of repeated embolization rather than by the administration of GM-CSF. The delay in systemic progression in the high-dose immunoembolization group suggests induction of a systemic immune response against uveal melanoma cells.

Based on these promising results, we conducted a randomized, double-blind phase II trial from 2005 to 2010 comparing immunoembolization to bland embolization. 30 Fifty-two patients were treated using either 2,000 μg GM-CSF or saline emulsified in ethiodized oil, followed by gelatin sponge to a point of near arterial stasis. The study was designed to compare immunologic outcomes. Peripheral blood specimens were drawn to measure GM-CSF and cytokine levels before and at two time points postprocedure. Treatment and follow-up were the same as described for the phase I trial, but the presence of extrahepatic metastasis was an exclusion from enrollment. All patients eventually developed progression of hepatic metastases, and no patients achieved a complete response. For patients with at least 20% tumor burden, there was a significant difference in median survival for the immunoembolization group (18.2 months) versus the bland embolization group (16.0 months). Survival was the same in both groups for those patients with less than 20% tumor burden, though we suspect that some patients experienced a paradoxical response to high-dose GM-CSF. A retrospective comparison shows that 1,500 μg GM-CSF may be a more appropriate dose for immunoembolization, and this is our current practice. 31 Nonetheless, this double-blind, randomized trial comparing bland embolization to immunoembolization showed a benefit of adding GM-CSF.

Our Phase II study was not powered to determine survival benefit. It was designed as a “proof of concept” study to investigate the hypothesis that adding GM-CSF to embolization would increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and delay the development of extrahepatic metastases. 28 Bland embolization alone produced a significant elevation in levels of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8, 18 hours postprocedure. Immunoembolization patients saw a rapid increase in tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-6, and IL-8 within an hour postprocedure, suggesting a faster and more robust inflammatory response than seen with bland embolization, along with a continued increase in IL-6 and IL-8 after 18 hours. An increased IL-6 level at 1 hour after treatment and increased IL-8 level at 18 hours correlated with a delay in onset of extrahepatic metastases in a dose–response pattern.

While it had been our practice to observe patients overnight in the hospital after immunoembolization to optimize treatment of postembolization syndrome and mild flulike symptoms, some patients are discharged the same day. Patients may experience hypotension and bradycardia shortly after the procedure. These side effects usually respond to a fluid bolus, though occasionally atropine administration is required. Patients undergoing treatment with immunoembolization should not receive steroids, as this could inhibit the intended immune response. When patients have iodinated contrast allergies, we perform immunoembolization using carbon dioxide or gadolinium agents as intravascular contrast.

We have retrospectively reviewed a group of 27 patients who underwent treatment with ipilimumab either shortly before or contemporaneously with initiation of immunoembolization. 32 The median survival in this group was 20.1 months. The addition of ipilimumab did not prevent the spread of disease as hoped; 89% of the 18 patients without extrahepatic metastases at the start of treatment eventually developed extrahepatic tumor. It appears that it is safe to perform this combination treatment, but patients often experienced typical toxicities associated with ipilimumab therapy. While steroid administration should be avoided in patients treated with immunoembolization, ipilimumab side effects often required treatment with steroids delaying further immunoembolization procedures. We are currently enrolling patients in a clinical trial evaluating treatment using immunoembolization along with ipilimumab and nivolumab (NCT03472586).

Despite the aggressive nature of this disease, a subset of patients may experience a prolonged survival. A retrospective analysis of 174 patients initially treated with immunoembolization showed that 16% had a prolonged survival of more than 3 years; 11% lived more than 4 years, and 5% survived more than 6 years. 33 Unfortunately, we currently are unable to predict which patients will achieve this long-term benefit, and approximately a third of patients experience progression of liver metastases despite immunoembolization. Nonetheless, immunoembolization remains our mainstay initial liver-directed treatment for patients presenting with limited tumor burden.

Radioembolization

The rationale for using radioembolization to treat uveal melanoma hepatic metastases is based on the excellent response of plaque radiotherapy for treatment of primary eye tumors. In 2009, Kennedy et al reported their results of a retrospective, multicenter study, using SIR-spheres (Sirtex Medical Inc., Woburn, MA) to treat 11 patients with uveal melanoma hepatic metastases. 34 Of the patients, 77% demonstrated a treatment response including one patient with a complete response following radioembolization. Stable disease was demonstrated in 11% of patients with the equivalent percentage of patients experiencing disease progression. Of the 10 patients with available follow-up, the 1-year survival was 80%.

In 2011, the authors reported their experience using resin microspheres as salvage therapy for 32 patients who failed alternative therapies including both immuno- and chemoembolization. 35 A dose reduction of 20% was applied to each patient due to multiple prior liver-directed therapies. Patients were divided into three groups based on pretreatment hepatic tumor burden: <25%, 25 to 50%, and >50%. Clinical follow-up ranged from 1.0 to 29.0 months (median: 10 months). At the conclusion of the follow-up period, 10 patients were alive 4.7 to 27.0 months (median: 9.4 months) following treatment. Twenty-two patients died 1.0 to 29.0 months (median: 5.8 months) following radioembolization due to disease progression ( n = 13), extrahepatic disease ( n = 4), or both ( n = 5). Median survival for the entire patient population was 10 months (range: 1.0–29.0 months). Patients with <25% tumor burden had a longer median survival than those with tumor burden greater than 25%: 10.5 versus 3.9 months, respectively. Treatment response included a complete response in one (3.1%) patient, partial response in one (3.1%) patient, stable disease in 18 (56.3%) patients, and progressive disease in 12 (37.5%) patients. Patients who had a response to treatment or stable disease had a longer median survival (14.7 months) compared with patients with disease progression (4.9 months). Progression-free survival of hepatic metastasis ranged from 1.0 to 26.5 months (median: 4.7 months) with a longer progression-free survival for patients with tumor burden less than 25% compared with those with tumor burdens greater than 25%: 6.4 versus 3.0 months, respectively. Toxicities following radioembolization were mild and self-limiting.

In 2013, Klingenstein et al published their results using radioembolization following failure of first-line therapies. 36 Eight (61.5%) patients achieved a partial response, two (15.4%) patients achieved stable disease, and three (23.1%) patients developed progressive disease. The median survival reported in this study was 7 months. In a retrospective review published in 2016, the authors reported a median survival of 12.3 months and a progression-free survival of 5.9 months following treatment of 71 patients with radioembolization. 37

In 2019, the authors published the first prospective radioembolization trial for the treatment of uveal melanoma hepatic metastases which included 24 treatment-naive patients (Group A) and 24 patients who progressed following immunoembolization (Group B). 38 Patients with tumor burdens less than 50% were included in the trial. We limited normal whole-liver parenchymal activity to a maximum of 35 Gy per patient based on reports of radiation-induced liver disease occurring in patients receiving more than 35 Gy of external radiation to normal liver parenchyma. Patients in Group A achieved a median survival of 18.5 months (range: 6.5–73.7 months) with 1-, 2-, and 3-year survivals of 60.9, 26.1, and 13.0%, respectively. One patient in Group A was excluded from the response to treatment data due to inability to treat all hepatic metastases with radioembolization. Hence, best radiographic response to treatment included a partial response in 9 (39.1%) patients, stable disease in 11 (47.8%) patients, and progression of disease in 3 (13.0%) patients. The median progression-free survival of hepatic metastasis was 8.1 months (range: 3.3–33.7 months) with all patients eventually developing new hepatic tumors. Extrahepatic disease developed or progressed in 91.3% of patients (median: 6.6 months; range: 3.3–33.7). Most common treatment-related toxicities included fatigue (91.7%) and nausea/vomiting (58.3%). Grade 3 treatment-related toxicities included nausea/vomiting ( n = 1), pain ( n = 2), and a transient lymphopenia ( n = 1). A median survival of 19.2 months (range: 4.8–76.6 months) was achieved for patients in Group B with 1-, 2-, and 3-year survivals of 69.6, 30.4, and 8.7%, respectively. The median survival following initial immunoembolization treatment was 24.7 months. Best radiographic response for Group B included a partial response in 8 (33.3%) patients, stable disease in 6 (25.0%), and progression of disease in 10 (41.7%) patients. Median progression-free survival of hepatic metastasis was 5.2 months (range: 2.9–22 months). Extrahepatic disease developed in 91.7% of patients (median: 4.7 months; range: 0.8–20.4 months). Similar to Group A, the most common treatment-related toxicities included fatigue (70.8%) and nausea/vomiting (58.3%). A transient Grade 3 lymphopenia occurred in one patient. Based on these results, radioembolization should be considered a safe and effective first- or second-line treatment for uveal melanoma hepatic metastases.

Based on our experience, we currently reserve radioembolization for patients presenting with hepatic tumor burdens less than 50%. We are currently conducting a multicenter trial using radioembolization in combination with systemic ipilimumab and nivolumab to determine safety and efficacy of this combination therapy in addition to determining if adding systemic therapy delays the development of extrahepatic disease (NCT-01730157).

Thermal Ablation

The majority of uveal melanoma patients who present with liver metastases have multifocal disease involving both lobes of the liver. Therefore, these patients are not appropriate for either surgical resection or ablative therapy. However, a small percentage of patients will present with oligometastatic or limited (<3 lesions) disease in the liver. It is in this subset of patients that percutaneous ablative therapy is supported, not only positively affecting survival but also providing meaningful treatment-free intervals, maximizing quality of life. Patient selection is of the utmost importance when considering ablative therapy. The surgical literature supports resection/ablation in patients with limited liver metastases that develop more than 5 years from the time of initial eye tumor diagnosis. 39 40 41 We follow these guidelines when managing patients with limited disease in the liver. This typically correlates with a more indolent tumor biology and avoids the scenario of detecting new liver metastases shortly after ablation in patients with more aggressive patterns of metastatic disease. Additionally, we recommend against performing multiple ablations, to preserve functional liver tissue, as patients will inevitably develop additional metastases and require future liver-directed therapies. We aim to create at least a 1-cm margin to ensure an “R0” ablation at the time of treatment. 42

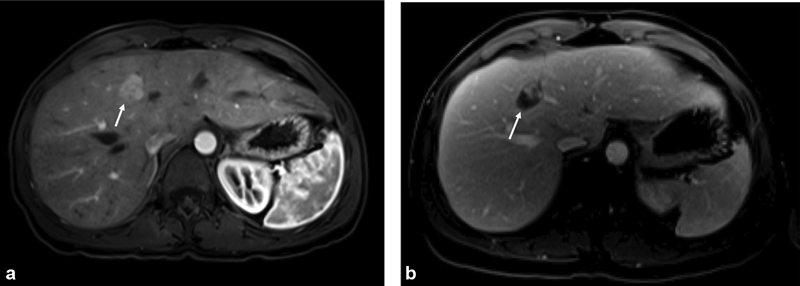

In addition to oligometastatic and limited metastatic disease, ablation can be safely employed in cases of a “rogue” tumor, defined as a single lesion not responding to embolization treatment with stability of all other lesions. In these scenarios, the goal of ablation is to eliminate the “rogue” tumor and lengthen the duration of liver-directed treatment currently controlling the growth of all other metastases ( Fig. 3a, b ).

Fig. 3.

( a ) Patient underwent multiple immunoembolization treatments with all tumors undergoing a complete response except for a “rogue” tumor in the medial segment of the left lobe of the liver seen on contrast-enhanced MRI (arrow). ( b ) “Rogue” tumor was treated with microwave ablation. Repeat MRI shows necrotic tumor in the ablation cavity (arrow). The patient is currently on a treatment break 7½ years after initiating liver-directed therapy.

Radiofrequency (RFA) and microwave (MW) thermal ablation modalities have been successfully used to treat patients with uveal melanoma, although the authors prefer MW ablation given its multiple inherent advantages. In a retrospective study, Mariani et al treated patients with RFA, both via open surgical and percutaneous approaches. When compared with surgical resection alone, 22 patients who underwent RFA with or without surgery had no statistical differences in overall survival (27 months) or progression-free survival (8 months). 41 Akyuz et al reported a 44-patient retrospective study comparing laparoscopic ablation/resection to systemic therapy in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma to the liver. Survival in the ablation group (35 months) was significantly longer than those receiving systemic therapy (15 months), although patients who received ablation had fewer tumors and more indolent tumor biology. 40 The authors presented a retrospective study in seven patients with oligometastatic disease who underwent percutaneous MW ablation. 41 Median progression-free survival was 8 months, with two patients showing no evidence of progression with follow-up as long as 26 months. Two patients died 23 and 24 months following ablation. An additional six patients with “rogue” tumors were treated with MW ablation. The median progression-free survival was 5 months, with stable disease in one patient at 28 months. Two patients died 16 and 26 months postablation. These studies are significantly limited given their retrospective and nonrandomized designs; however, in appropriately selected patients with uveal melanoma hepatic metastases, thermal ablation is safe and effective and may offer meaningful treatment-free intervals and survival benefits.

Systemic Therapies

There is no FDA approved standard of care for metastatic uveal melanoma. However, the understanding of its biology has evolved such that ongoing immunotherapy and targeted investigational therapies have rapidly become available as potential treatment options. An important principal underpinning of all treatment strategies is the fact that cutaneous melanoma and uveal melanoma are distinct disease entities. Uveal melanoma is far better at evading immune detection, possibly related to a lower mutational load than cutaneous melanoma. 43 This helps explain why therapies, which have shown such promise in cutaneous melanoma, have been disappointing in the uveal melanoma population.

Immunotherapies

Unlike cutaneous melanoma where immune checkpoint inhibition has become a mainstay of treatment, use of anti-PD-1 (nivolumab and pembrolizumab), anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab), and anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) has been far less effective for uveal melanoma. Multiple small trials and retrospective reviews of patients receiving these checkpoint inhibitors have shown poor response rates (3–17%), and progression-free survival of approximately 3 months and overall survival of less than 1 year. Although disease control rate has been shown to be 30 to 60% in these trials, durability has been poor. Additionally, toxicities are significant, particularly when combining anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies, where grade 3 or higher adverse events have been reported in more than 50% of patients. 44 45 46 47

A new class of drug named immune-mobilizing monoclonal T-cell receptors against cancer (ImmTACs) marks a new treatment strategy, whereby the drug serves as a “magnet” pulling T-cells to the melanoma cells. 48 This helps solve the ability of melanoma cells to successfully evade immune surveillance. The drug, tebentafusp (IMCgp100), requires a certain tissue type, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-0201–restricted gp100 peptide, which is present in approximately 50% of patients. In both the first in-human and phase I study for metastatic uveal melanoma, tebentafusp has shown promising results with excellent durability, with a disease control rate of 71% and durable disease control rate of 41%. Progression-free survival was 6 months and 1-year overall survival was 75%. Additionally, the adverse event profile is much more favorable than that of immune check point blockade. 48 49

Adoptive T-cell therapy with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is an intensive treatment strategy by which lymphocyte cells are harvested from the patient during metastatectomy. These cells are grown in vitro and subsequently infused back into the patient with high-dose IL-2 following lymphodepleting chemotherapy. A phase II trial of 20 patients showed one complete response, an overall response rate of 35%, and a disease control rate of 43%; however, durability was poor. 50

Targeted Therapies

The most common mutations on molecular sequencing in uveal melanoma are GNAQ and GNA11, which are both activating mutations. These mutations are distinct from cutaneous melanoma where mutations in BRAFV600E are common and have been successfully targeted with FDA-approved oral medications. At present, there is no current therapy which specifically targets the most common mutations in uveal melanoma. However, there have been clinical trials of agents targeting the downstream signaling pathways with limited responses. 51 Carvajal et al evaluated the MEK inhibitor, selumetinib, in randomized phase II and phase III (SUMIT) trials when comparing it to the chemotherapeutic agent, dacarbazine; however, ultimately, the phase III study did not show any significant benefit in progression-free survival and overall response rates. 52 53 A phase I study of sotrastaurin, a pan-PKC inhibitor, showed a disease control rate of 47% and a progression-free survival of 4 months. 54 Combination regimens with PKC and MEK inhibitors have not been sufficiently studied. Many additional targets have been identified with early studies ongoing; however, results have failed to show meaningful benefit.

Imaging Surveillance

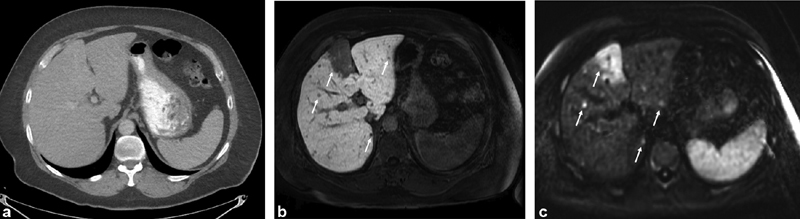

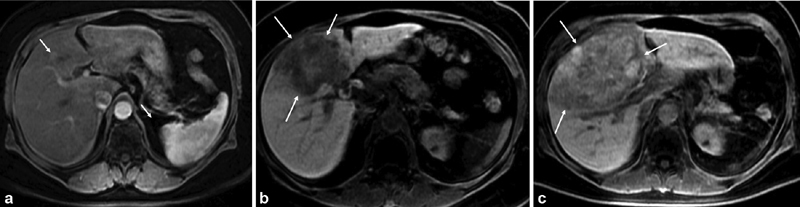

Given that most patients with early metastatic uveal melanoma have normal laboratory values and are asymptomatic, cross-sectional imaging remains the cornerstone for the detection of metastatic disease. Patients with a diagnosis of uveal melanoma should undergo routine surveillance imaging at a minimum of twice-yearly intervals for early detection of metastases. As the liver by far represents the organ most involved with metastases, abdominal MRI at 1.5 or 3 Tesla is the modality of choice with the highest sensitivity for detecting hepatic metastases. Contrast-enhanced MRI using gadoxetate disodium (Eovist) is superior to CT in the detection of small hepatic metastases ( Fig. 4a–c ). As normally functioning hepatocytes retain Eovist, uveal melanoma metastases will stand out in contrast to normal liver parenchyma. 55 Diffusion-weighted sequences are also remarkably sensitive in depicting melanoma metastases and should be included as part of the MRI exam. 55 Ultrasound is highly operator dependent and should be discouraged for standard surveillance. CT imaging is important for the detection of extrahepatic metastases.

Fig. 4.

( a ) Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen (portal venous phase) demonstrates no definite liver tumors. ( b ) Contrast-enhanced (Eovist) MRI performed the same day as the CT demonstrates several tumors on the hepatobiliary phase and ( c ) diffusion-weighted imaging including a large tumor in the medial segment of the left lobe of the liver (arrows).

Similar to screening and surveillance, MRI remains the imaging modality of choice to assess treatment response in patients with hepatic metastases. To most accurately determine treatment response, we underscore the importance of obtaining contemporaneous baseline imaging prior to initiation of treatment. Significant delays between baseline imaging and treatment can confuse interpretation of imaging when determining treatment efficacy given the aggressive nature of this disease ( Fig. 5a–c ). Standardized response criteria are typically used to assess treatment response. In specific instances, such as patients receiving immunotherapy, one must consider employing immune-related response criteria to most accurately characterize response and guide management. 56

Fig. 5.

( a ) Contrast-enhanced MRI of the abdomen demonstrates a small tumor in the medial segment of the left lobe (arrows). A repeat MRI was ordered by the patient's local oncologist. ( b ) Four months later, repeat MRI demonstrates significant tumor growth (arrows). Patient referred to our institution for treatment. ( c ) Repeat MRI performed ∼4 weeks later demonstrates rapid tumor progression highlighting the need for contemporaneous imaging prior to liver-directed treatment (arrows).

Discussion

Over the past several decades, with the advent of various liver-directed therapies, overall survival for patients with uveal melanoma hepatic metastases has been prolonged. In a retrospective review, Moser et al published their experience treating metastatic uveal melanoma patients between 2000 and 2013 with systemic therapy ( n = 88), liver-directed therapy ( n = 46), or both ( n = 36). 57 Patients who received liver-directed therapy had a longer median survival than patients treated with systemic therapy: 26 versus 9.1 months, respectively. In addition, liver-directed treatment was the only therapy that significantly improved overall survival, while systemic therapy showed no significant survival benefit in their patient population.

More recently, the authors published a retrospective review of patient outcomes extending over the course of our institution's 47-year experience treating this disease. 58 We compared overall survival for patients treated between 1971 and 1993 (Cohort 1; n = 80), 1998 and 2007 (Cohort 2; n = 198), and 2008 and 2017 (Cohort 3; n = 452). Seventy percent of patients in Cohort 1 received only first- and second-line systemic (DTIC-based chemotherapy) therapy for the treatment of liver metastases, while 98% of patients in Cohorts 2 and 3 received first- and second-line liver-directed treatments alone or with systemic therapies. The median survivals from the diagnosis of liver metastases to death for patients in Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 were 5.3, 13.6, and 17.8 months, respectively. The 1- and 2-year survivals for Cohort 1 were 23 and 8%, respectively. The 1- and 2-year survivals for Cohort 2 and Cohort 3 were 5% and 28% and 67 and 35%, respectively. There was no difference among the cohorts based on gender or location and stage of the primary eye tumors. Despite the similar characteristics of the primary eye tumors, median survival after treatment of the primary eye tumor was 40.8 months in Cohort 1, but increased to 62.6 months in Cohort 2 and 59.4 months in Cohort 3, supporting the use of liver-directed treatments when patients develop metastases. Therefore, overall survivals improved for patients in Cohorts 2 and 3 who were primarily treated with liver-directed therapies.

Although, there are inherent weaknesses in these retrospective studies, we feel strongly that liver-directed therapy for the treatment of uveal melanoma hepatic metastases is beneficial to prolonging survival for patients with this disease. More importantly, the majority of liver-directed therapies have limited side effects and provide patients with good quality of life between scheduled treatments. The benefit of adding systemic therapies to liver-directed treatments is still unknown. However, as previously mentioned, we are currently conducting two separate trials using immuno- or radioembolization and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Given that the systemic treatment, Tebentafusp, has shown potential survival benefit for patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, combination therapy with liver-directed treatments may further prolong patient survival and should be the focus of future clinical trials.

Conflicts of Interest None declared.

Disclosures

D.J.E. received a consultation payment from Rosalind Advisors, an investor in Delcath.

References

- 1.Aronow M E, Topham A K, Singh A D. Uveal melanoma: 5-year update on incidence, treatment, and survival (SEER 1973–2013) Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2018;4(03):145–151. doi: 10.1159/000480640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaliki S, Shields C L. Uveal melanoma: relatively rare but deadly cancer. Eye (Lond) 2017;31(02):241–257. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields C L, Shields J A. Ocular melanoma: relatively rare but requiring respect. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(01):122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulmer A, Beutel J, Süsskind D. Visualization of circulating melanoma cells in peripheral blood of patients with primary uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(14):4469–4474. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krantz B A, Dave N, Komatsubara K M, Marr B P, Carvajal R D. Uveal melanoma: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of primary disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:279–289. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S89591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J, Manson D K, Marr B P, Carvajal R D. Treatment of uveal melanoma: where are we now? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1.758834018757175E15. doi: 10.1177/1758834018757175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Bosch T, van Beek J GM, Vaarwater J. Higher percentage of FISH-determined monosomy 3 and 8q amplification in uveal melanoma cells relate to poor patient prognosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(06):2668–2674. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassoux N, Rodrigues M J, Plancher C. Genome-wide profiling is a clinically relevant and affordable prognostic test in posterior uveal melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(06):769–774. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onken M D, Worley L A, Char D H. Collaborative ocular oncology group report number 1: prospective validation of a multi-gene prognostic assay in uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(08):1596–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field M G, Decatur C L, Kurtenbach S. PRAME as an independent biomarker for metastasis in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(05):1234–1242. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato T. Locoregional management of hepatic metastasis from primary uveal melanoma. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(02):127–138. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spagnolo F, Caltabiano G, Queirolo P. Uveal melanoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(05):549–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedikian A Y, Legha S S, Mavligit G. Treatment of uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver: a review of the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience and prognostic factors. Cancer. 1995;76(09):1665–1670. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951101)76:9<1665::aid-cncr2820760925>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mavligit G M, Charnsangavej C, Carrasco C H, Patt Y Z, Benjamin R S, Wallace S. Regression of ocular melanoma metastatic to the liver after hepatic arterial chemoembolization with cisplatin and polyvinyl sponge. JAMA. 1988;260(07):974–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogl T, Eichler K, Zangos S. Preliminary experience with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in liver metastases of uveal malignant melanoma: local tumor control and survival. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133(03):177–184. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0155-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S, Bedikian A Y, Ahrar J. Hepatic artery chemoembolization in patients with ocular melanoma metastatic to the liver: response, survival, and prognostic factors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33(05):474–480. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181b4b065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huppert P E, Fierlbeck G, Pereira P. Transarterial chemoembolization of liver metastases in patients with uveal melanoma. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(03):e38–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato T, Nathan F E, Berd D, Sullivan K, Mastrangelo M J. Lack of effect from chemoembolization for liver metastasis from uveal melanoma. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1995;14:415. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin S W. The current practice of transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10(05):425–434. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.5.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel K, Sullivan K, Berd D. Chemoembolization of the hepatic artery with BCNU for metastatic uveal melanoma: results of a phase II study. Melanoma Res. 2005;15(04):297–304. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200508000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonsalves C F, Eschelman D J, Thornburg B, Frangos A, Sato T. Uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver: chemoembolization with 1,3-bis-(2-Chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(02):429–433. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.14001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan A L, Eschelman D J, Gonsalves C F, Frangos A, Sato T. Treatment of bulky uveal melanoma hepatic metastases with doxorubicin drug-eluting beads (DEBDOX) followed by 1,3-bis-(2-Chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU): an initial experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(03):S45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiorentini G, Aliberti C, Del Conte A. Intra-arterial hepatic chemoembolization (TACE) of liver metastases from ocular melanoma with slow-release irinotecan-eluting beads. Early results of a phase II clinical study. In Vivo. 2009;23(01):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venturini M, Pilla L, Agostini G. Transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads preloaded with irinotecan as a first-line approach in uveal melanoma liver metastases: tumor response and predictive value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in five patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(07):937–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes M S, Zager J, Faries M. Results of a randomized controlled multicenter phase III trial of percutaneous hepatic perfusion compared with best available care for patients with melanoma liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(04):1309–1319. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4968-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karydis I, Gangi A, Wheater M J. Percutaneous hepatic perfusion with melphalan in uveal melanoma: a safe and effective treatment modality in an orphan disease. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117(06):1170–1178. doi: 10.1002/jso.24956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Artzner C, Mossakowski O, Hefferman G. Chemosaturation with percutaneous hepatic perfusion of melphalan for liver-dominant metastatic uveal melanoma: a single center experience. Cancer Imaging. 2019;19(01):31–38. doi: 10.1186/s40644-019-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato T, Eschelman D J, Gonsalves C F. Immunoembolization of malignant liver tumors, including uveal melanoma, using granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5436–5442. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto A, Chervoneva I, Sullivan K L. High-dose immunoembolization: survival benefit in patients with hepatic metastases from uveal melanoma. Radiology. 2009;252(01):290–298. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2521081252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valsecchi M E, Terai M, Eschelman D J. Double-blinded, randomized phase II study using embolization with or without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in uveal melanoma with hepatic metastases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(04):523–3200. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutjahr C J, Gonsalves C F, Eschelman D J, Frangos A, Meshekow J S, Sato T. Immunoembolization (IE) using 1500 mcg of granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and 2 million IU of interleukin-2 (IL-2) for the treatment of uveal melanoma (UM) hepatic metastases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:S26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guez D, Eschelman D, Pan K. Ipilimumab combined with immunoembolization for treatment of uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver. J Vasc Radiol. 2019;30:S141. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford R, Gonsalves C, Adamo R. Prolonged survival after treatment of hepatic uveal melanoma metastases using immunoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:S140. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy A S, Nutting C, Jakobs T. A first report of radioembolization for hepatic metastases from ocular melanoma. Cancer Invest. 2009;27(06):682–690. doi: 10.1080/07357900802620893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonsalves C F, Eschelman D J, Sullivan K L, Anne P R, Doyle L, Sato T. Radioembolization as salvage therapy for hepatic metastasis of uveal melanoma: a single-institution experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(02):468–473. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klingenstein A, Haug A R, Zech C J, Schaller U C. Radioembolization as locoregional therapy of hepatic metastases in uveal melanoma patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(01):158–165. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eldredge-Hindy H, Ohri N, Anne P R. Yttrium-90 microsphere brachytherapy for liver metastases from uveal melanoma: clinical outcomes and the predictive value of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39(02):189–195. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonsalves C F, Eschelman D J, Adamo R D. A prospective phase II trial of radioembolization for treatment of uveal melanoma hepatic metastasis. Radiology. 2019;293(01):223–231. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019190199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aoyama T, Mastrangelo M J, Berd D. Protracted survival after resection of metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89(07):1561–1568. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1561::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akyuz M, Yazici P, Dural C. Laparoscopic management of liver metastases from uveal melanoma. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(06):2567–2571. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariani P, Almubarak M M, Kollen M. Radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection of liver metastases from uveal melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(05):706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mariani P, Piperno-Neumann S, Servois V. Surgical management of liver metastases from uveal melanoma: 16 years' experience at the Institut Curie. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35(11):1192–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Croce M, Ferrini S, Pfeffer U, Gangemi R. Targeted therapy of uveal melanoma: recent failures and new perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(06):846. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimmer L, Vaubel J, Mohr P. Phase II DeCOG-study of ipilimumab in pretreated and treatment-naïve patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. PLoS One. 2015;10(03):e0118564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heppt M V, Heinzerling L, Kähler K C. Prognostic factors and outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with programmed cell death-1 or combined PD-1/cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 inhibition. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Algazi A P, Tsai K K, Shoushtari A N. Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer. 2016;122(21):3344–3353. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piulats Rodriguez J M, De La Cruz Merino L, Espinosa E. Phase II multicenter, single arm, open label study of nivolumab in combination with Ipilimumab in untreated patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:442–466. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sato T, Nathan P D, Hernandez-Aya L. Redirected T cell lysis in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma with gp100-directed TCR IMCgp100: overall survival findings. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:9521. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carvajal R D, Sacco J, Nathan P. Safety, efficacy and biology of the gp100 TCR-based bispecific T cell redirector IMCgp100 in advanced uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:3622. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandran S S, Somerville R, Yang J C. Treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma with adoptive transfer of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: a single-centre, two-stage, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(06):792–802. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sterbis E, Gonsalves C F, Shaw C. Safety and efficacy of microwave ablation for uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(03):S84. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carvajal R D, Sosman J A, Quevedo J F. Effect of selumetinib vs chemotherapy on progression-free survival in uveal melanoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2397–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carvajal R D, Piperno-Neumann S, Kapiteijn E. Selumetinib in combination with dacarbazine in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: a phase III, multicenter, randomized trial (SUMIT) J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1232–1239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piperno-Neumann S, Kapiteijn E, Larkin J. Phase I dose-escalation study of the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor AEB071 in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:9030. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balasubramanya R, Selvarajan S K, Cox M.Imaging of ocular melanoma metastasis Br J Radiol 201689(1065):2.0160092E7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang G X, Kurra V, Gainor J F. Immune checkpoint inhibitor cancer therapy: spectrum of imaging findings. Radiographics. 2017;37(07):2132–2144. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moser J C, Pulido J S, Dronca R S, McWilliams R R, Markovic S N, Mansfield A S. The Mayo Clinic experience with the use of kinase inhibitors, ipilimumab, bevacizumab, and local therapies in the treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2015;25(01):59–63. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seedor R S, Eschelman D J, Gonsalves C F. An outcome assessment of a single institution's longitudinal experience with uveal melanoma patients with liver metastasis. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(01):117. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]