Abstract

Only two major mast cell (MC) subtypes are commonly recognized in the mouse: the large connective tissue mast cells (CTMC) and the mucosal mast cells (MMC). Interepithelial mucosal inflammatory cells, most commonly identified as globule leukocytes (GL), represent a third MC subtype in mice, which we term interepithelial mucosal mast cells (ieMMC). This term clearly distinguishes ieMMCs from lamina proprial MMCs (lp MMCs) while clearly communicating their common MC lineage. Both lpMMCs and ieMMCs are rare in normal mouse intestinal mucosa, but increased numbers of ieMMCs are seen as part of type-2 immune responses to intestinal helminth infections and in food allergies. Interestingly, we found that increased ieMMCs were consistently associated with decreased mucosal inflammation and damage, suggesting that they might have a role in controlling helminth-induced immunopathology. We also found that ieMMC hyperplasia can develop in the absence of helminth infections, for example in Treg-deficient mice, Arf null mice, some nude mice, and in certain graft-versus-host responses. Since tuft cell hyperplasia plays a critical role in type-2 immune responses to intestinal helminths, we looked for (but did not find) any direct relationship between ieMMC and tuft cell numbers in the intestinal mucosa. Much remains to be learned about the differing functions of ieMMCs and lpMMCs in the intestinal mucosa, but an essential step in deciphering their roles in mucosal immune responses will be to apply IHC methods to consistently and accurately identify them in tissue sections.

Keywords: graft-versus-host, Heligmosomoides bakeri, mast cell, mouse, Treg, Trichuris muris, immunohistochemistry

Mouse models have been invaluable in elucidating the origin, differentiation, and diverse functions of mast cells (MCs) as well as their roles in the pathogenesis of several diseases.62, 69, 95, 110, 112, 152 MCs located in mucosal tissues can respond rapidly to pathogens or other agents that breach epithelial barriers.63, 153 Although they are probably best known for their role in mediating IgE-associated allergic reactions in asthma, anaphylaxis, food allergies and inflammatory bowel disease, it has become increasingly clear that MCs comprise a heterogeneous cell population that can secrete many different biologically active products affecting a wide range of physiologic processes.38, 71, 77, 78, 118, 119 MC products may be stored in secretory granules (e.g., histamine, heparin, various proteases) or produced de novo upon cell stimulation (e.g., prostaglandins, leukotrienes, cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors).72, 73, 209 MC-derived factors can influence both effector and regulatory T cell responses,86 and many other pathophysiological processes including wound healing, angiogenesis, fibrosis, and neoplasia.33, 153 MCs also have anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive functions that can reduce tissue injury in innate and adaptive immune responses.34, 60, 63, 70 Recently, mast cell-derived proteases were shown to enhance resistance to venom-induced pathology and mortality by degrading venom toxins.61, 192

The original identification of MCs in 1878 by Paul Ehrlich was based on the metachromatic histochemical staining of prominent cytoplasmic granules within large cells in connective tissue.39 Approximately 50 years ago, Enerback identified two major subsets of MCs in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of rats44, 45 and mice,25, 26 based on their differing sizes, locations, and staining characteristics. These subtypes were connective tissue mast cells (CTMCs) and mucosal mast cells (MMCs). In the gastrointestinal tract, the classic large CTMCs are widely dispersed within submucosa, serosa, and mesentery of the GI tract whereas smaller MMCs are normally quite rare and restricted to the lamina propria. Importantly, Enerback found that several different histochemical stains could be used to detect CTMCs in tissues fixed in a wide range of fixatives (including formalin), but the detection of MMCs was possible only if tissues were fixed with Carnoy’s or a weak formaldehyde and acetic acid mixture.44, 45, 47 These differences in histochemical staining were attributed to the abundance of heparin in the secretory granules of CTMCs,155, 213 whereas MMCs granules contained predominantly chondroitin sulfates and glycosaminoglycans.184

Enerback also described the characteristics of a third cell type in the intestinal mucosa which is still called the globule leukocyte in many species.44, 45 These cells have been reported in the intestinal, respiratory, and urogenital systems of many species, including rats and mice, sheep, goats, cattle, dogs, cats, birds, and humans.25, 26, 46, 82, 92, 102, 103, 108, 123, 187, 189 Until recently, GLs have most often been identified on the basis of their morphology and location because of the lack of specific molecular markers.197 They have sometimes been misidentified as eosinophils,13 but can generally be distinguished histologically by their larger eosinophilic intracytoplasmic globules, small round or bilobed nucleus, low nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, and their location between intestinal epithelial cells.29, 92, 116, 177 Interestingly, GLs have rarely been reported in mice in recent decades, although they are still frequently described in rats, ruminants, and other species.

Abundant evidence has accumulated since Enerback’s reports showing that GLs actually represent a third major type of MC in rodents. As a result, we will use the term interepithelial mucosal mast cell (ieMMC) in this report to clearly identify these cells as MCs and to distinguish them from other (usually invisible) mucosal mast cells which are generally located in the lamina propria (lpMMCs). The derivation of both ieMMCs and lpMMCs mucosal mast cells from a common precursor is supported by a variety of histochemical and immunohistochemical studies. In rats, the cytoplasmic granules in both lpMMCs and ieMMCs contain glycosaminoglycans, serine esterases, and rat mast cell protease-II (RMCPII), suggesting a close relationship between these two cell types.91 The presence of high-affinity IgE receptor (FCER1A) on both GLs and MMCs, and fact that ieMMCs only produce granzyme B following IgE-dependent stimulation via FCER1A also indicate that ieMMCs are derived from MC precursors.92, 197

The near disappearance of GLs from the mouse immunology literature appears to be due both to the rarity of lpMMCs in normal mice in comparison to rats and other species35, 135 and the “invisibility” of lpMMCs unless special fixation and staining methods are used. In contrast, ieMMCs are easily identified in routinely (formalin) fixed tissue sections, with the end result that the distinction between ieMMCs and lpMMCs in mice has been largely unrecognized, and GLs are usually classified as MMCs in those studies where they are mentioned at all. However, the substantial differences between lpMMCs and ieMMCs in terms of morphology, location, granule contents, and immunohistochemical staining characteristics156, 161, 164 indicate that ieMMCs probably have significantly different functions than lpMMCs, and thus should not be equated with them.

We observed ieMMC hyperplasia in several different mouse model systems and used specific immunohistochemical (IHC) staining methods to reliably detect and differentiate ieMMCs from otherwise invisible lpMMCs in formalin-fixed mouse intestines. Since tuft cell hyperplasia has recently been reported to play a critical role in type-2 immune responses to intestinal helminths, we also used IHC methods to look for relationships between ieMMCs, lpMMCs, and tuft cells in mice showing ieMMC hyperplasia. Tuft cells are taste-chemosensory cells in the intestinal mucosa that appear to proliferate in response to intestinal helminth infections and initiate type-2 immune reactions.65, 66, 88, 199 Much remains to be learned about the differing functions of ieMMCs and lpMMCs in mucosal immune responses, and the application of IHC methods will be necessary to consistently and accurately identify them in tissue sections.

Materials and Methods

Archival tissues

The specific mouse lines and experiments included in this report (nematode infected, Foxp3DTR, p19ARF null mice and CD1 nude mice) were selected for inclusion in this retrospective study from hundreds of different experiments involving mice because they showed increased ieMMCs in hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained sections of either small or large intestine. Since affected mouse lines were on predominantly C57BL/6 or BALB/c genetic backgrounds, we used sections of small and large intestine from normal C57BL/6 (n = 20) and BALB/c (n = 15) mice aged between 12 and 20 weeks to evaluate the normal distribution and numbers of ieMMCs, lpMMCs, and tuft cells in those mouse strains. We also evaluated MMC numbers in Foxp3DTR mice (n = 10) that had not been Treg depleted.

All the experiments included in this report were included in animal protocols that had been approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities (tested and negative for Sendai virus, mouse parvovirus [MPV], minute virus of mice [MVM], mouse hepatitis virus [MHV], Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus, epizootic diarrhea of infant mice [EDIM], pneumonia virus of mice [PVM], reovirus, K virus, polyoma virus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [LCMV], mouse adenovirus [MAV], ectromelia virus, as well as murine ecto- and endoparasites) in the SJCRH Animal Resource Center.

Immunohistochemistry

All FFPE tissues were sectioned at 4 μm, mounted on positively charged glass slides (Superfrost Plus; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and dried at 60°C for 20 min. A variety of histochemical (HE, PAS, toluidine blue, Luna) and immunohistochemical (CD117/c-kit, mast cell tryptase, granzyme B, MCPT1, and MCPT4) methods were tested and compared (Table 1). For detection of ieMMCs, sections underwent antigen retrieval at 100°C for 20 min in Epitope Retrieval solution 2 (ER2) on a Bond Max immunostainer (Leica Biosystems, Bannockburn, IL). A rat monoclonal primary antibody to mast cell protease 1 (MCPT1;Cat# 14-5503-82; eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) diluted 1:30 was applied for 15 minutes followed by biotinylated secondary rabbit anti-rat antibody diluted 1:400 (BA-4001; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 10 minutes and then ready-to-use Bond polymer refine detection kit with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as chromogenic substrate and a hematoxylin counterstain (DS9800; Leica Biosystems). For detection of lpMMCs and tuft cells, tissue sections underwent antigen retrieval in a prediluted Cell Conditioning Solution (CC1) (Ventana Medical Systems, Indianapolis, IN) for 32 min. For lpMMCs, a goat polyclonal antibody to mast cell protease 4 (MCPT4; LS-B5958; LifeSpan Biosciences, Seattle, WA) was diluted 1:500 and applied for 30 min at RT followed by biotinylated secondary rabbit anti-goat antibody 1:400 (BA-5000; Vector Laboratories) for 10 minutes. For detection of tuft cells, a rabbit polyclonal antibody to doublecortin like kinase 1 (DCAMKL1;ab31704; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) diluted 1:1,000 was applied for 30 min at RT followed directly by the OmniMap anti-Rabbit HRP kit (Ventana Medical Systems) for detection, with Discovery Purple as chromogen for lpMMCs and ChromoMap DAB for tuft cells (both from Ventana Medical Systems).

Table 1:

Reactivity, source, optimal dilution, epitope retrieval procedure, optimal dilution, and visualization system for each of the primary antibodies

| Target | ieMMC | lpMMC | CTMC | Type | Source (catalog #) | Optimal Dilution | Heat-induced epitope retrieval# | Visualization systemϕ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCPT1 | + | − | − | Rat anti mouse mast cell protease 1 monoclonal antibody (clone RF6) | eBioscience (14-5503-82) | 1:30 | ER2 (20 min) | RB-RT-Bond DAB |

| MCPT4 | − | + | + | Goat anti-mouse mast cell protease 4 (aa114–126) polyclonal antibody | LifeSpan Biosciences (LS-B5958) | 1:500 | CC1 (32 min) | RB-GT/OM RB PURPLE |

| Mast Cell Tryptase | − | + | + | Mouse anti-human mast cell tryptase monoclonal antibody (clone AA1) | Dako (M7052) | 1:100 | TR PC110 (15 min) | MM Quanto DAB |

| Granzyme B | + | +/− | + | Rabbit anti-human granzyme B (aa20–38) polyclonal antibody | abcam (ab4059) | 1:1,000 | ER2 (20 min) | RB-RF-Bond DAB |

| CD117/c-kit | + | + | + | Goat anti-mouse CD117/c-kit polyclonal antibody | R&D (AF1356) | 1:1,000 | CC1 (32 min) | OM GT Ventana DAB |

| DCAMKL1 | − | − | − | Rabbit anti-mouse DCAMKL1 (C-terminus) polyclonal antibody | abcam (ab31704) | 1:1,000 | CC1 (32 min) | OM RB Ventana DAB/PURPLE |

Epitope retrieval:

ER2: Epitope Retrieval solution 2(Leica Biosystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL)

CC1: Cell conditioning 1 (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc. Tuscon, AZ)

TR PC110:Target Retrieval solutions (Dako) in Decloaking Chamber (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) at 110C

Visualization systems:

RB-RT-Bond DAB: Secondary antibody is biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG Antibody (BA-4001; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); Bond Polymer Refine Detection (DS9800: Leica Biosystems)

RB-GT/OM RB PURPLE:Biotinylated rabbit anti-goat IgG secondary antibody (BA-5000; Vector Laboratories), DISCOVERY OmniMap anti-Rb HRP (760–4311; Ventana Medical); DISCOVERY Purple kit (760–229; Ventana Medical)

MM QUANTO DAB: UltraVision Quanto Mouse on Mouse HRP polymer (TL-015-QPHM; Thermo Scientific); DAB Quanto Substrate (TA-125-QHSX; Thermo Scientific)

RB-RF-DAB: Bond Polymer Refine Detection (DS9800; Leica Biosystems)

OM GT Ventana DAB: DISCOVERY OmniMap anti-Gt HRP (760–159; Ventana Medical); DISCOVERY ChromoMap DAB Kit (760–159; Ventana Medical)

OM RB DAB/PURPLE: DISCOVERY OmniMap anti-Rb HRP (760–4311; Ventana Medical); DISCOVERY Purple kit (760–229; Ventana Medical) or DISCOVERY ChromoMap DAB Kit (760–159; Ventana Medical)

Trichuris muris infections

In order to investigate the effects of Treg depletion on mucosal immune responses to nematode infections, we used B6.129(Cg)-Foxp3tm3(DTR/GFP)Ayr/J (Foxp3DTR) mice originally provided by A.Y. Rudensky (Sloan-Kettering Institute).106 Foxp3DTR mice are transgenic for a bacterial artificial chromosome expressing a diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor-enhanced GFP fusion protein under the control of the Foxp3 gene locus.121 For T. muris experiments involving Foxp3DTR mice, embryonated eggs were generated as previously described4 and mice were infected by oral gavage with 30 embryonated eggs in a volume of 200μl (low-dose infection) at 8–10 weeks of age. As previously published,167 these mice were infected with T. muris eggs via oral gavage on day 0, followed by Treg depletion (Early versus Late) by five intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injections of 10μg/kg diphtheria toxin (DT) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 200μl of sterile PBS or sterile PBS alone, and harvested on day 35. For the “Early DT” experiments, mice were administered DT during the initial stages of infection (days 0–8), whereas “Late DT” involved Treg depletion once the infection was established (days 9–17). In these experiments, Treg were allowed to recover and tissues were harvested on day 35 post-infection and assessed for mucosal inflammation.167 Tissues from the same 8 uninfected Foxp3DTR mice treated with DT used in the Heligmosomoides bakeri infections described below were used to determine the effects of global Treg cell depletion on the cecal and colonic intestinal mucosa.

Heligmosomoides bakeri (formerly H. polygyrus11) infections

These experiments used ensheathed third stage Heligmosomoides bakeri larvae kindly provided by Dr. De’Broski R. Herbert (University of California San Francisco).85, 194 Foxp3DTR were inoculated on day 0 with 200 larvae via oral gavage, and then dosed intraperitoneally with 10ug/kg of diphtheria toxin (DT) on days 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 after infection, with small intestines harvested at day 17 and fixed by immersion in 10% NBF. The four different treatment groups included in this experiment consisted of: a) uninfected mice (n = 7) not dosed with DT (untreated controls); b) mice (n = 14) dosed with 200 H. bakeri larvae only; c) mice (n = 8) that received DT treatments only; and d) mice (n = 17) given 200 H. bakeri larvae via oral gavage on day 0 followed by 10ug/kg of DT via intraperitoneal injection on days 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

Sections of colon were obtained from previously reported experiments that were designed to study factors that influence the severity of graft-versus-host disease.171, 196 These experiments involved transplantations of bone marrow and spleen between two MHC-incompatible mouse strains. In one set of experiments BALB/cJ (H-2d) donor cells were transplanted into irradiated C57BL/6J (H-2b) recipients, while in the others C57BL/6J (H-2b) donor cells were transplanted into irradiated BALB/cJ (H_2d) recipients. Recipient mice received either myeloablative total body irradiation (TBI) or non-myeloablative total lymphoid irradiation (TLI) delivered to the lymph nodes, thymus, and spleen with shielding of the skull, lungs, limbs, pelvis and tail as previously reported.149, 196 The donor transplants consisted of bone marrow only (negative control not expected to develop GVHD), or a mixture of spleen and bone marrow cells (positive control expected to develop GVHD). All recipient mice were included in this study.

p19ARF null mice

Tissues were obtained from 117 mice (4–20 months of age) undergoing routine histopathological evaluations intended to determine the locations and types of spontaneous neoplasms developing in p19ARF null mice (129svj X C57BL/6 background).98

CD-1® nude mice

Routine histopathological evaluations were performed on 18 CD-1 nude mice (Crl:CD1-Foxn1nu) that were being used in xenograft research studies.

Results

Normal C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice

Only two MC types were detected in HE-stained sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) mouse tissues. First, there were large connective tissue mast cells (CTMCs) present in the dermis (Fig. 1) and many other locations. Second, there were the much smaller ieMMCs with characteristic eosinophilic granules which are rarely seen (0–5 in the entire intestinal tract) in normal C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice but are present in large numbers in helminth-infected mice (Fig. 2). In contrast to the ieMMCs and occasional submucosal CTMCs, the small lpMMCs were undetectable in FFPE tissues stained with HE (Fig. 3). In comparing a variety of histochemical (HE, PAS, toluidine blue, alcian blue, Luna) and immunohistochemical staining methods (CD117/c-kit, mast cell tryptase, granzyme B, MCPT1, and MCPT4), we determined that IHC using antibodies to MCPT1 and MCPT4 provided the most sensitive and specific way to detect and differentiate the two major classes of intestinal MMCs in mice. We found that the cytoplasmic granules of lpMMCs (unlike those of CTMCs) were not visible with toluidine blue, PAS, alcian blue, HE or any other tested histochemical stain in formalin-fixed tissues. While they could be detected using antibodies to CD117/c-kit or mast cell tryptase we found that specific detection of lpMMCs was best accomplished using anti-MCPT4 antibodies (Fig. 4). After completing initial surveys, we decided to use the anti-MCPT1 antibodies to specifically label ieMMCs, because several other cell types (including CTMCs) express CD117/c-kit and/or granzyme B. In the occasional cases where rare ieMMCs were not easily detected in HE sections (Fig. 5), they were still reliably labeled using antibodies to MCPT1, along with the otherwise invisible lpMMCs being labeled with anti-MCPT4 antibodies (Fig. 6).

Figure 1.

Dermis, mouse. The prominent dark blue cytoplasmic granules in large connective tissue mast cells (CTMC) are preserved in formalin fixed tissues. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE).

Figure 2.

Colon, mouse. The red cytoplasmic granules in globule leukocytes/ interepithelial mucosal mast cells are visible in formalin fixed tissues. HE.

Figure 3.

Small intestine, mouse. CTMCs (arrows) and ieMMCs are visible in formalin fixed tissues, but lamina proprial mast cells (lpMMC) are not. HE.

Figure 4.

Small intestine, immunohistochemistry (IHC) for MCPT1 and MCPT4, mouse. The small ieMMCs are positive for MCPT1 (brown). MCPT4 (violet) labels both the small lp MMCs and the larger submucosal CTMCs, but they can be distinguished by their differences in location and size.

Figure 5.

Colon, mouse. Small ieMMCs (arrows) can be difficult to identify and lpMMC are not visible in standard HE stained sections.

Figure 6.

Colon, (sequential section of Fig. 5), IHC for MCPT4 and MCPT4, mouse. Small ieMMCs (brown) and lpMMCs (violet) are present.

IHC labeling of wild-type C57BL/6 (n = 20) and BALB/c (n = 20) intestines with anti-MCPT1 antibodies showed that ieMMCs were generally uncommon (<1 per 10 villi) in normal small intestine mucosa (Fig. 7). Labeling of lpMMCs with anti-MCPT4 antibodies showed that lpMMCs were rare (usually <1 per 100 villi) in normal small intestine, although they occasionally occurred in clusters in individual villi (not shown). In the normal large intestine, both lpMMCs and ieMMCs were rare (<1 per 100 crypts) to absent (Fig. 9).

Figures 7.

Small intestine, IHC for MCPT1, mouse. ieMMCs (arrow) are rare in normal small intestine mucosa.

Figures 9.

Colon, IHC for MCPT1, mouse. ieMMCs are also rare in normal colon mucosa.

Because both ieMMCs1, 9, 37, 80, 92, 101, 134, 136, 139, 178, 180, 181, 204, 208, 214 and tuft cells67, 68, 92, 209 increase following intestinal nematode infections,65, 66, 88, 199,65, 66, 88, 199,65, 66, 88, 199,65, 66, 88, 199,66, 67, 91, 204,66, 67, 91, 204 we were interested in uncovering any temporal or spatial relationships between these two cell types in the intestinal mucosa. To this end, we used antibodies to doublecortin like kinase 1 (DCAMKL1) to specifically detect tuft cells. We found that tuft cells were widely distributed but present only in small numbers in both the small (Fig. 8) and large intestine (Fig. 10) of normal uninfected C57BL/6 mice (generally no more than 2 per villus in small intestine and 1 per crypt in large intestine).

Figures 8.

Small intestine, IHC for DCAMKL1, mouse. Tuft cells are scattered diffusely in normal small intestine mucosa.

Figures 10.

Colon, IHC for DCAMKL1, mouse. Tuft cells are rare (arrow) in normal colon mucosa.

Trichuris muris-infected Foxp3DTR mice

In T. muris-infected Foxp3DTR mice with normal Treg numbers, ieMMC hyperplasia in the cecum and proximal colon (Fig. 11) was generally accompanied by increased number of tuft cells (Fig. 12) and eosinophils (not shown) in most areas of the mucosa. There was no notable increase in lpMMC numbers, which remained rare (usually <1 per 100 villi) although a few clusters were found in one mouse. The submucosal and subserosal lymphatics were frequently distended by large numbers of lymphocytes (Figs 11–14). Interestingly, numbers of ieMMCs and tuft cells were often not increased within the mucosa immediately adjacent to the parasite attachment sites (Figs. 13 and 14). The long thin anterior end (stichosome) of T. muris forms syncytial tunnels that are composed of host epithelial cells (Fig. 15). The areas with minimal infiltrates of ieMMCs and tuft cells at these attachment sites were often sharply demarcated (Figs. 16 and 17). Increased ieMMC and tuft cell numbers were restricted to the T. muris-infected cecum and proximal colon, with essentially normal distribution and numbers in the small intestine or middle and lower colon of infected mice (not shown).

Figure 11. Trichuris muris infected cecum, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. There is diffuse ieMMC hyperplasia in the mucosa associated with lymphocytic infiltrates and edema in the mucosa and submucosa. Submucosal lymphatics are dilated by accumulated lymphocytes.

Figure 12. Trichuris muris infected cecum, mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. There is a diffuse increase in numbers of tuft cells in the cecal mucosa.

Figure 14. Trichuris muris infected cecum, mouse.

The number of tuft cells is also reduced in the general area of T. muris attachment.

Figure 13. Trichuris muris infected cecum, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. The severity of ieMMC hyperplasia is reduced in the immediate vicinity of T. muris attachment sites.

Figure 15. Trichuris muris infected cecum, mouse.

The anterior end of T. muris attaches to the mucosa by forming tunnels consisting of host cells forming syncytia (arrow). The adjacent mucosa is hyperplastic and lacks goblet cells; the lamina propria contains abundant eosinophils and lymphocytes.

Figures 16. Trichuris muris infected cecum, mouse.

Cecum, mouse (high magnification of Fig. 13). IHC for MCPT1. The zone of reduced ieMMCs (brown) is limited to the immediate vicinity of the helminths.

Figures 17. Trichuris muris infected cecum, mouse.

Cecum, mouse (high magnification of Fig. 14). IHC for DCAMKL1. A more extensive zone of reduced tuft cells (brown) is often present around helminth attachment sites.

As we previously reported,167 both the appearance and the extent of mucosal inflammation in Treg-depleted mice were influenced by the timing of Treg depletion via DT treatment. Those T. muris-infected Foxp3DTR mice that were given DT at early time points had a reduced helminth burden and only developed minimal to mild mucosal inflammation and edema, which was often associated with mucosal epithelial hyperplasia and rare focal ulcerations. Surprisingly, Treg depletion at the early time points did not appear to have any notable effect on ieMMC or tuft cell numbers. In these mice, diffuse ieMMC hyperplasia (Fig. 18) was usually not accompanied by diffusely increased tuft cells (Fig. 19) and only mildly increased eosinophils and lpMMCs (Fig. 20).

Figure 18. Trichuris muris infected cecum, Treg depletion at early time points, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. There is diffuse ieMMC (brown) hyperplasia in the mucosa.

Figure 19. Trichuris muris infected cecum, Treg depletion at early time points, mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. Tuft cells (brown) are rare in the cecal mucosa.

Figure 20. Trichuris muris infected cecum, Treg depletion at early time points, mouse.

IHC for MCPT4. There are scattered lpMMCs (violet) in the cecal mucosa.

In marked contrast, T. muris-infected Foxp3DTR mice treated with DT at late time points had higher helminth burdens than mice with early Treg depletion, and developed a more severe and diffuse inflammatory response, often accompanied by extensive ulceration and submucosal edema. In these mice, both ieMMCs (Fig. 21) and tuft cells (Fig. 22) were essentially absent in the cecal mucosa, and goblet cells were markedly decreased in number. However, lpMMCs were diffusely increased (Fig. 23) and usually accompanied by prominent eosinophil infiltrates around the crypts and in the submucosa.

Figure 21. Trichuris muris infected cecum, Treg depletion at late time points, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. ieMMCs (brown) are very rarely present in the diffuse mucosal hyperplasia and more severe inflammatory cell infiltrates.

Figure 22. Trichuris muris infected cecum, Treg depletion at late time points, mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1.Tuft cells (brown) are also very rare in the hyperplastic cecal mucosa.

Figure 23. Trichuris muris infected cecum, Treg depletion at late time points, mouse.

IHC for MCPT4. There are increased numbers of lpMMCs (violet) in the lamina propria and submucosa.

Heligmosomoides bakeri-infected Foxp3DTR mice

In marked contrast to the relatively uniform distribution of low numbers of ieMMCs and tuft cells in the small intestine of normal mice, infections of normal mice with H. bakeri resulted in markedly increased numbers of all three cell types (ieMMCs, lpMMCs, and tuft cells) in the small intestinal mucosa (Figs. 24, 25, and 26). Interestingly, the distribution and severity of these cell infiltrates in the mucosa appeared to be inversely related to their proximity to adult helminths in the lumen; much higher densities of ieMMCs, lpMMCs, and tuft cells were present in the helminth-free ileum than in the helminth-infected proximal small intestine. A similar pattern was observed in the proximal small intestine, where very few ieMMCs (Fig. 27) and tuft cells (Fig. 28) were found in the mucosa immediately adjacent to intraluminal parasites, but elevated numbers were located in the intervening mucosa. The intestinal tracts of H. bakeri consistently showed MCPT1-positive contents (Figs. 27 and 29), unlike T. muris, which were never immunoreactive.

Figure 24. Heligmosomoides bakeri infected duodenum, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. Diffuse ieMMC hyperplasia is present in mucosa not in direct contact with helminths.

Figure 25. Heligmosomoides bakeri infected duodenum, mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. Diffuse tuft cell hyperplasia is present in mucosa not in direct contact with helminths.

Figure 26. Heligmosomoides bakeri infected duodenum, mouse.

IHC for MCPT4. Increased numbers of lpMMCs are present in mucosa not in direct contact with helminths.

Figure 27. Heligmosomoides bakeri infected duodenum, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. ieMMCs are absent in the mucosa in direct contact with helminths but MCPT1 is present in helminth digestive tract (arrows).

Figure 28. Heligmosomoides bakeri infected duodenum, mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. Tuft cells are also absent in the mucosa in direct contact with helminths.

Figure 29. Heligmosomoides bakeri infected duodenum, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. The helminth digestive tracts (arrows) consistently contain MCPT1-positive material.

Unexpectedly, both ieMMCs and tuft cells in the H. bakeri-infected Treg-depleted mice were less numerous and widespread in all areas of the small intestine than in the uninfected Treg-depleted mice. In contrast to the diffuse distribution of both ieMMCs and tuft cells in uninfected Treg-depleted mice, there was uneven distribution of these cells in Treg-depleted mice with concurrent H. bakeri infections, where scattered clusters of ieMMCs and tuft cells were widely separated by extensive zones containing relatively few cells of either type. In both normal and Treg-depleted mice, both ieMMCs and tuft cells were often absent in the shortened villi typically present adjacent to the intraluminal parasites.

Uninfected Treg deficient Foxp3DTR mice

The depletion of Treg cells (via DT treatment) in uninfected mice was associated with crypt hyperplasia and a diffuse increase in both ieMMCs (4–10 per villus) and tuft cells (often >10 per villus) throughout the small intestine (Figs. 30 and 31). ieMMCs also tended to be increased in the large intestine, although their distribution was patchy (Fig. 32) and the numbers of lpMMCs and tuft cells were often not noticeably increased above background levels in those areas with ieMMC hyperplasia (Fig. 33).

Figure 30. Small intestine and colon, Treg-depleted DEREG mice.

IHC for MCPT1. Diffuse ieMMCs (brown) hyperplasia is present in the small intestine mucosa.

Figure 31. Small intestine and colon, Treg-depleted DEREG mice.

IHC for DCAMKL1. Increased tuft cells (brown) are present throughout the small intestine mucosa.

Figure 32. Small intestine and colon, Treg-depleted DEREG mice.

IHC for MCPT1. Diffuse ieMMCs (brown) hyperplasia is present in the colon mucosa.

Figure 33. Small intestine and colon, Treg-depleted DEREG mice.

IHC for DCAMKL1. In contrast, there is no notable increase in tuft cells (brown) in the same region of colon mucosa.

Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD)

In the GVHD experiments, irradiated BALB/cJ (H-2d) recipients of C57BL/6J (H-2b) donor cells typically developed an acute onset lethal form of GVHD characterized by extensive mucosal damage in the colon, with crypt abscesses, single-cell necrosis, inflammation and ulceration. ieMMCs were never detected in the intestinal mucosa of BALB/cJ mice that received C57BL/6J donor cells. In contrast, irradiated C57BL/6J mice that received BALB/cJ donor cells developed a milder, later-onset GVHD phenotype, characterized by diffuse mucosal hyperplasia, mild inflammation, and multifocal mucosal ulcers in only a subset of animals. Interestingly, increased ieMMCs were present in the cecum and/or colon (and distal ileum) of 35/46 (76%) of C57BL/6J mice that had received both TBI and transplantation of combined spleen and bone marrow cells from BALB/cJ donors (Fig. 34). Interestingly, the numbers of tuft cells were not increased in areas with ieMMC hyperplasia (Fig. 35) but the numbers of lpMMCs (Fig. 36) and eosinophils were often markedly increased. In fact, tuft cells were generally absent or rare in the mucosal areas with increased ieMMCs. However, none of the C57BL/6J recipients that had undergone total lymphoid irradiation (TLI) or received only bone marrow (not spleen) transplants developed ieMMC hyperplasia.

Figure 34. Graft versus host disease (GVHD), colon, mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. Diffuse ieMMCs (brown) hyperplasia is present in the colon mucosa.

Figure 35. Graft versus host disease (GVHD), colon, mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. In contrast, there is no notable increase in tuft cells (brown) in the colon mucosa.

Figure 36. Graft versus host disease (GVHD), colon, mouse.

IHC for and MCPT1 and MCPT4. Scattered ieMMCs (brown) and Clusters of lpMMCs (violet) within the lamina propria are common in GVHD-affected colon mucosa.

p19ARF null mice

Immunohistochemical staining for MCPT1, MCPT4, and DCAMKL1 was completed on the 32/117 (27%) cases that had visible ieMMCs within the small and/or large intestinal mucosa by HE staining. Variable ieMMC hyperplasia was identified as an incidental finding in p19ARF null mice having at least one of several different types of tumors, which included sarcomas, osteosarcomas, lung carcinoma, periorbital carcinoma, B cell lymphoma/leukemia, T cell lymphoma/leukemia, and plasmacytomas. The ieMMC infiltrates could be focal, segmental, patchy, or diffuse in the small and/or large intestine. The distribution of infiltrates ranged from widely separated or individual foci involving as few as 2–5 villi to diffuse involvement of the entire intestinal tract (both small and large intestine). In most cases, the ieMMCs were primarily located between intestinal epithelial cells but in severe cases they also appeared in large numbers in the lamina propria (Fig. 37), sometimes accompanied by increased tuft cells (Fig. 38). However, the numbers and distribution of lpMMC and ieMMCs was highly variable, with some mice showing prominent infiltrates and others having very few, and there was no apparent correlation between the increased numbers of ieMMCs in the mucosa and numbers of tuft cells (Figs. 39 and 40). In a few locations, both were present in large numbers, but tuft cell numbers were often low even in areas with marked ieMMC hyperplasia (Figs. 41 and 42). Conversely, there were also some foci where tuft cells were increased but ieMMCs absent (not shown).

Figure 37. Small intestine and colon, p19ARF null mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. Severe interepithelial and lamina proprial hyperplasia of ieMMCs (brown) in the small intestine mucosa.

Figure 38. Small intestine and colon, p19ARF null mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. Tuft cell (brown) hyperplasia can be present in the same areas of mucosa.

Figure 39. Small intestine and colon, p19ARF null mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. The ieMMC (brown) hyperplasia in p19ARF null mice often has a patchy distribution.

Figure 40. Small intestine and colon, p19ARF null mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. This sequential section, illustrates the lack of correlation between tuft cell (brown) numbers and ieMMC hyperplasia.

Figure 41. Small intestine and colon, p19ARF null mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. Diffuse ieMMCs (brown) hyperplasia is present in the colon mucosa.

Figure 42. Small intestine and colon, p19ARF null mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. In contrast, there is no notable increase in tuft cells (brown) in the colon mucosa.

CD-1® nude mice

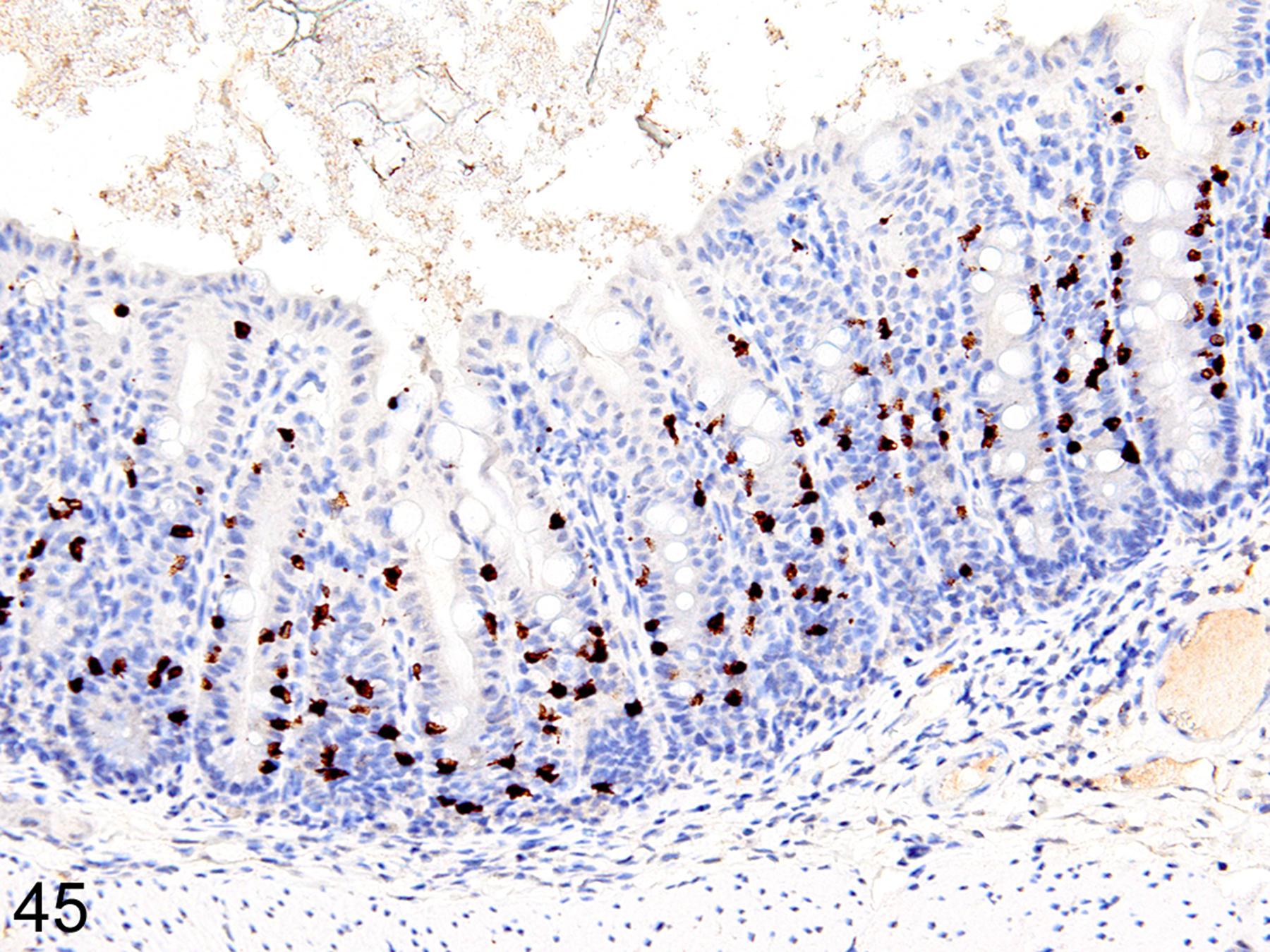

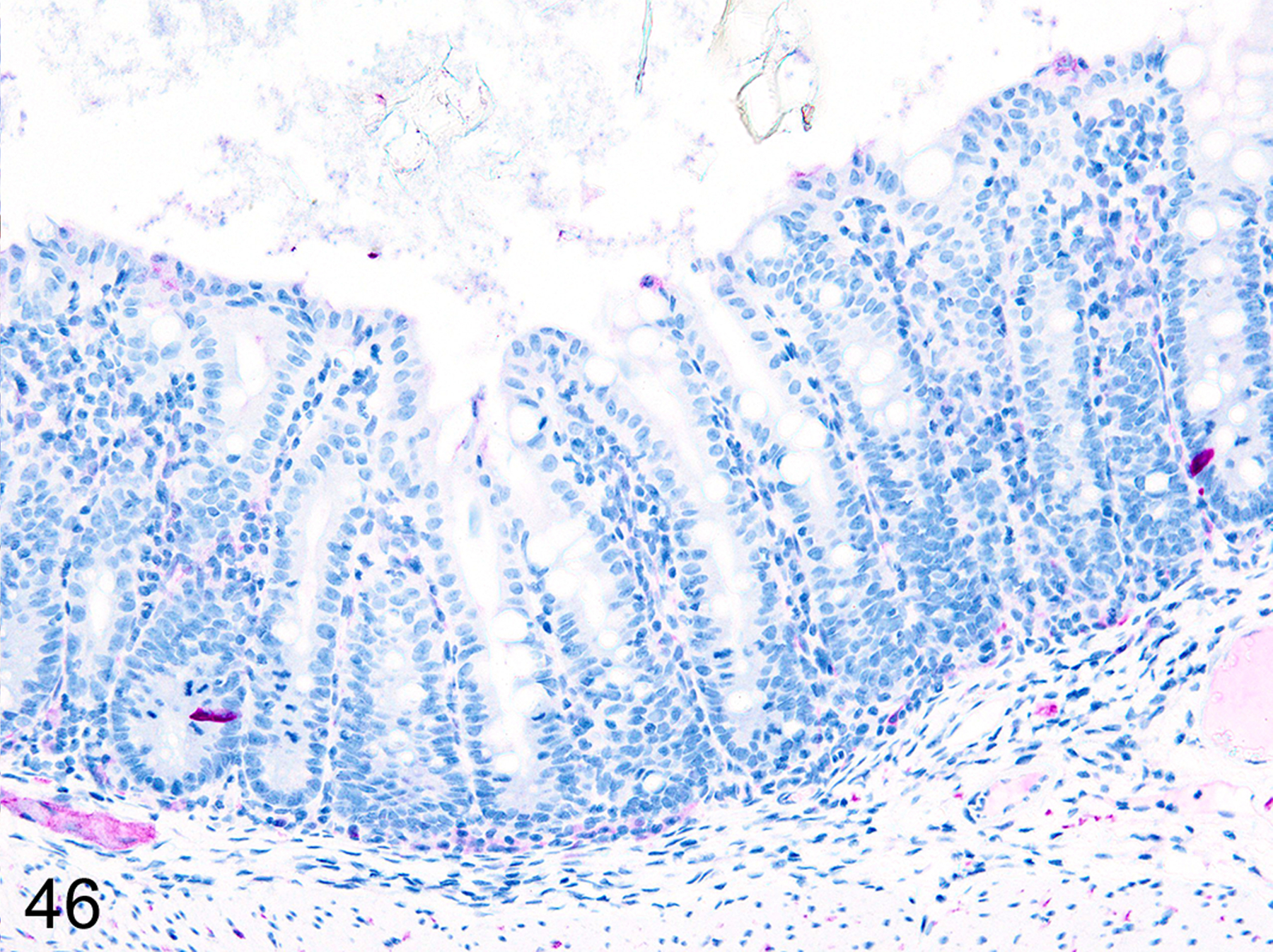

Immunohistochemical staining for MCPT1, MCPT4, and DCAMKL1 was completed on the 6/18 cases showing visible ieMMCs within the small and/or large intestinal mucosa by HE staining. The distribution and severity of ieMMC infiltrates in the nude mice were variable, ranging from diffuse to patchy in both the small and large intestinal mucosa. Although ieMMC hyperplasia in the small intestine of nude mice (Fig. 43) was sometimes associated with mild increases in tuft cells (Fig. 44), even the most severe ieMMC infiltrates in the colon (Fig. 45) were usually not accompanied by increased numbers of lpMMC tuft cells (Fig. 46) or lpMMCs (not shown).

Figure 43. Small intestine and colon, CD-1 nude mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. Diffuse ieMMC (brown) hyperplasia in the small intestine mucosa.

Figure 44. Small intestine and colon, CD-1 nude mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. This sequential section shows tuft cell (violet) hyperplasia is often present in the same areas of small intestine mucosa.

Figure 45. Small intestine and colon, CD-1 nude mouse.

IHC for MCPT1. Diffuse ieMMC (brown) hyperplasia in the colon mucosa.

Figure 46. Small intestine and colon, CD-1 nude mouse.

IHC for DCAMKL1. This sequential section, illustrates the lack of correlation between tuft cell (violet) numbers and ieMMC hyperplasia in the colon mucosa

Discussion

MCs in mice and rats have traditionally been classified into two distinct subpopulations designated as connective tissue mast cells (CTMC) and mucosal mast cells (MMC) based on differences in location, morphology, and granule contents.8, 18, 24, 50, 63, 72, 109, 111, 134 However, further distinctions between mucosal mast cell subtypes in mice are possible based on their differential expression of mast cell proteases (MCP). In mice, the constitutive lpMMCs express a different set of enzymes than the ieMMCs.58, 72, 154, 183 Similarly, the major mast cell subtypes recognized in humans differ in granule contents,27 with some containing mainly tryptase and others containing both tryptase and chymase.30 Three different MMC phenotypes in humans are distinguished based on their differing serine-protease contents, with the most common type (60–65%) containing both tryptase and chymase (MCTC), followed by ~30% of MMCs containing tryptase but no chymase (MCT), and finally ~10% containing chymase but no tryptase (MCC).19 However, these present classifications are grossly oversimplified because MCs can express many different combinations of serine proteases in secretory granules, suggesting the existence of many more types of mast cells.67, 137, 154

One possible explanation for the inconsistent and sometimes even contradictory functions attributed to MCs is mast cell heterogeneity, which is reflected by the wide range of histological, histochemical, and biochemical, differences they display.202 Morphologically, mouse MCs vary markedly in size and granule contents, and can show variable nuclear profiles, including segmented and multilobular nuclei.74 Differences in morphology and histochemical staining characteristics reflect the heterogeneity in granule contents and thus functions of the various MC subtypes.8, 10, 47, 59, 89, 135, 183 Although mast cell heterogeneity in the GI tract has long been recognized,5, 17, 18, 99, 169 very few recent reports clearly distinguish between those mucosal mast cells that are typically located within the lamina propria (lpMMCs) and the interepithelial mucosal mast cells (ieMMCs, most often known as globule leukocytes).93

In contrast to other species, mast cells appear to be rare in the intestinal mucosa of normal mice.57, 135, 137 However, by using sensitive and specific IHC assays for MCPT1 and MCPT4, we were able to localize large numbers of two distinctly different MMC populations in the intestinal mucosa of some mice. The IHC methods we used were preferable to traditional histochemical stains (e.g., toluidine blue, safranin, and methylene blue) for MCs because they enabled the detection of otherwise invisible lpMMCs in formalin-fixed tissues. This is important because neutral buffered formalin is the most commonly used fixative in most laboratories. It is widely known that preservation and staining of MC granules are highly dependent on the type of tissue fixatives used. In human tissues, the use of Carnoy’s fixative is recommended for any light microscopic study of human MMCs,185 and even dermal CTMCs are negatively affected by formalin fixation128 Similarly, the cationic stains commonly used to detect CTMCs in skin and other connective tissues of mice and rats are not effective for identifying MMCs unless special fixation methods and staining protocols are applied.44–48, 182, 184, 185, 206 We believe that the scarcity of reports describing lpMMCs in mouse studies is largely due to the widespread use of formalin/paraformaldehyde in tissue fixation, both of which would preclude staining of cytoplasmic granules in lpMMCs (although not ieMMCs).

One other unexpected but important finding that emerged from our analysis of archived tissues obtained from several different studies was the importance of prompt fixation of tissues after death for reliable identification of both ieMMCs and lpMMCs. In fact, rapid fixation of tissues was absolutely essential for detection of lpMMCs, as they could not be seen anywhere within the small intestinal mucosa of samples containing even partially autolyzed villi. Suboptimal fixation did not appear to have any effect on the histochemical or immunohistochemical staining of cytoplasmic granules of CTMCs. Interestingly, ieMMCs could still be detected by IHC in sections that contained poorly fixed/partially autolysed mucosa, even when they were no longer visible with HE staining (not shown). Our inability to detect lpMMCs in partially autolyzed tissues even with IHC methods further supports the notion that the cytoplasmic granules in these cells are particularly labile.

Nematode infections

The massive influx of ieMMCs and tuft cell hyperplasia that we observed in the intestinal mucosa of wild type mice following infection with T. muris and H. bakeri was not unexpected given that intestinal nematode infections typically induce a dominant Th2 response in which type 2 cytokines such as interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-9, IL-10 and IL-13 induce ieMMC hyperplasia.148 Indeed, ieMMC hyperplasia is associated with Th2 responses to helminth infections in many different species, where ieMMCs are believed to play roles in clearing the parasites and possibly reducing immune-mediated damage to the mucosa.1, 9, 37, 80, 92, 101, 134, 136, 139, 178, 180, 181, 204, 208, 214 Our IHC results also support recent reports indicating a role for tuft cells in sensing and responding to intestinal helminth parasite infections.6, 66, 105 Generally, the numbers of tuft cells and ieMMCs in intestinal epithelium both increase markedly following nematode infection, and mice lacking functional tuft cells have reduced type 2 responses and delayed parasite expulsion.66 Tuft cells release IL-25,199 which activates innate lymphoid cells to produce cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and/or IL-13) that are typically associated with mucosa-protective type 2 immune responses.6, 66, 105

In the other conditions where we observed ieMMC hyperplasia in the absence of nematode infections, we were surprised to find that tuft cell numbers were not necessarily increased in areas with ieMMC hyperplasia, and conversely that some areas of mucosa with increased tuft cells did not necessarily contain ieMMCs. These findings suggest that tuft cells do not directly induce ieMMC hyperplasia, and also show that tuft cell hyperplasia does not necessarily have to be induced by luminal parasites. Indeed, IL-4Rα signaling alone was recently shown to be sufficient to induce tuft cell expansion.66

The ieMMC hyperplasia we observed in the intestinal mucosa following infection with both T. muris and H. bakeri was generally restricted to the helminth-infected segment of intestine, which is consistent with previous reports47, 101, 134, 136 For example, the small intestinal parasites Trichinella spiralis and H. bakeri induce ieMMC hyperplasia in the mouse small intestine,162, 165 whereas Trichuris muris infection is associated with a marked intraepithelial ieMMC response limited to the cecal mucosa.96 The dominant ieMMC response to nematodes in mice differs from that seen in rats; in mice the ieMMCs comprise up to 90% of the mast cell response,124, 161whereas in rats there are essentially equal numbers of ieMMCs and lpMMCs.136

Nevertheless, ieMMC hyperplasia is clearly important in the expulsion of many intestinal parasites. In ruminants, a strong ieMMC response is associated with resistance to a wide range of nematode parasites, including O. ostertagi, Trichostrongylus colubriformis, and H. contortus.20, 37, 64, 81, 87, 178, 179 Studies in mast cell-deficient mice and rats have established the importance of ieMMC hyperplasia in resistance against many but not all nematode parasites, including H. bakeri36, 49, 53, 75, 84, 129, 138, 141 and Trichinella spiralis.2, 144 However, ieMMCs do not appear to have an important a role in expelling Trichuris muris from the large intestine.16, 84

The mucosal lesions and ieMMC hyperplasia that we observed in Foxp3DTR mice with normal Treg numbers were essentially the same as those reported in many other studies using low dose exposures in normal mice. During a low-dose infection, resistant Th2-biased mouse strains (such as BALB/k) clear T. muris infection more quickly than less resistant Th1 biased strain (C57BL/6).43 Generally, Th2 polarized responses (IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13) help clear T. muris infections in resistant mice.42, 193

We found that the severity of inflammatory responses and helminth clearance in DT-treated (and thus Treg depleted) Foxp3DTR mice depended on when during infection the Tregs were depleted. With Treg depletion at early time points, our mice displayed the relatively mild mucosal inflammation and damage plus ieMMC hyperplasia typical of a Th2 response.167 In contrast, Treg depletion later in the course of infection resulted in a Th1 response, characterized by severe inflammation, edema, and ulceration, with both ieMMCs and tuft cells being absent in the cecal mucosa. The importance of temporal effects on host responses were shown in another study,96 where resistant mice developed moderate mucosal inflammation with ieMMC hyperplasia, and cleared T. muris within 3 weeks, whereas mice subjected to transient immunosuppression around the time of infection developed a persistent parasite infection characterized by fewer ieMMCs and more severe, mixed, mucosal and submucosal inflammation with crypt damage. Thus, replacement of the Th2 T helper cell response to nematode infections by a Th1 response results in increased severity and persistence of colitis in response to Trichuris infection.96 Again, ieMMC hyperplasia was a prominent feature in the Th2 responses associated with milder mucosal lesions, suggesting a possible role for MMCs in modulating inflammatory responses in the gut mucosa.

Heligmosomoides bakeri (formerly known as H. polygyrus)11 establishes long-term chronic infections in the distal small intestine in most mouse strains, with CBA and C57BL/6 mice being fully susceptible. However, SJL and SWR mice are able to expel these helminths quickly while BALB/c mice are only partially susceptible.52, 200 Increased susceptibility is associated with increased Treg activation, IFN-γ expression by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and elevated IgE levels52 In contrast, resistant mouse strains reduce helminth egg production and survival via more sustained and intense Type 2 immune responses characterized by increased production of IL-4, IL-9, and IL-10, eosinophilia and alternatively activated macrophages.52, 200 After parasites are cleared, a protective Th2 memory response reacts quickly to later challenge infections.193, 194 Expulsion of H. bakeri correlates with ieMMC hyperplasia12 and elevated intestinal fluid levels of mMCP-1 in several mouse strains.14 Transgenic mice overexpressing IL-9 have marked ieMMC hyperplasia and are completely resistant to H. bakeri infections. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest a central role for ieMMCs in establishing protective immunity.83 Although immune-mediated clearance of gastrointestinal helminth parasites has long been associated with increased ieMMCs, the precise effector mechanisms responsible for their antihelminthic activity are still not fully understood.3, 145, 147

The systemic and intraluminal release of chymases (chymotrypsin-like serine proteases) from ieMMCs has been linked to decreased fecundity and helminth expulsion in both ruminants and rodents.36, 90, 115, 131, 134, 170 We believe that the presence of MCPT1 staining within the intestinal tract of H. bakeri and its absence in T. muris may be due to the differing feeding habits of these two parasites, and also may help explain the differing effects of ieMMC hyperplasia on their survival. Since H. bakeri actively grazes on surface mucosal epithelium7 (almost certainly including ieMMCs), it necessarily ingests ieMMC-derived granzyme B and chymases that could be toxic to adult helminths. In contrast, T. muris inserts its narrow anterior into the subepithelial space and feeds on serum and other tissue components, thereby avoiding ingestion of ieMMCs and their presumably toxic contents. In cattle, exocytosis of granules containing granulysin from ieMMCs correlates with vaccine-induced protection against O. ostertagi.197 In mice, massive amounts of mouse mast cell protease-1 (mMCPT-1),90, 142 are expressed and released by ieMMCs in response to helminth infections169, 201 and levels of mMCPT-1 in the bloodstream and intestinal lumen are maximal at the time of helminth expulsion.90, 115 Additional evidence for the importance of ieMMC-specific responses in controlling intestinal parasites infections is provided by the delayed expulsion of helminths reported in both mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice31 and mouse mast cell protease-1 (mMCPT-1)-deficient mice.115, 122 An alternative “leak lesion hypothesis” proposes that mMCP-1 from ieMMCs increases mucosal permeability, and promotes helminth expulsion via the release of antibodies and other mediators into the lumen107, 140, 159, 168, 170 However, a ieMMC-associated leak lesion mechanism does not explain T. muris resistance to ieMMC hyperplasia.

The reduced number of ieMMCs and tuft cells we observed in the immediate vicinity of H. bakeri is not altogether surprising given the potent immunomodulatory effects this parasite is known to exert on the murine immune system. In order to survive for extended time in their hosts, helminths induce a Th2 cytokine environment characterized by downregulation of Th1 and Th17 responses in the mucosa,40, 172, 210 upregulation of IL-10 and TGF-β by Treg cells,79, 172 and the induction of alternatively activated macrophages in the intestinal mucosa.54, 203 The anti-helminth type-2 responses include innate immune cells such as eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, alternatively activated or type 2 (M2) macrophages, and type 2 ILC2, which in turn respond to or secrete the type 2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.143 These Th2-type responses play an important role in limiting acute tissue damage during helminth infection.28

Primary infection with H. bakeri downregulates secretion of IL-9 and IL-10, which correlates with reduced ieMMC numbers and increased long-term survival of adult helminths.12 These effects have been attributed to the production and release of H. bakeri “Excretory-Secretory” (HES) antigens, which include a TGF-beta-like ligand that induces de novo regulatory T cells127, 132, 133 These HES antigens convert naive T cells into Foxp3+ Tregs via the TGFβ pathway68 and the activated Tregs block protective Th2 immunity.205 Treg induction by HES appears to be part of this parasite’s strategy for long-term survival in the intestine, but these immunomodulatory properties extend beyond the intestinal mucosa and can suppress inflammation in many autoimmune, allergic, and immunological disorders.32, 150, 198, 215 In animal models of airway allergies, the administration of HES proteins reduces allergic airway inflammation.133 In mice, helminth-associated immunosuppression creates a bystander effect that reduces autoimmune or allergic responses in models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and colitis.117, 120, 125, 157, 176

Similarly, epidemiological studies in humans suggest that parasitic infections reduce the incidence of allergy/asthma and autoimmunity,195, 211 and the increased incidence of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases in developed nations has been attributed to improved hygiene and the disappearance of intestinal helminth infections and suggests the potential use of parasite antigens to downregulate systemic allergic and autoimmune conditions.49, 127, 132 In humans, helminth therapy has shown promise in treating TH1/TH17-mediated inflammatory disorders such as multiple sclerosis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease in humans.41, 55, 186 In recent years, many clinical trials have tested the potential therapeutic effects of helminth infections.56 It is possible that ieMMCs could play a role in the beneficial effects associated with helminth therapy for other immune-mediated disease.

In addition to the known association of ieMMC hyperplasia with nematode infections, we found increased mucosal ieMMCs in other settings, including mice with Treg deficiencies, specific types of intestinal graft versus host disease, in otherwise unremarkable athymic nude mice, and in a high proportion of p19ARF null mice.98

Treg depleted mice

The ieMMC hyperplasia we observed with Treg depletion or functional deficiencies is similar to that seen as part of the mucosal Th2 response induced by nematode infections, except that Treg deficiencies resulted in the infiltration and differentiation of ieMMCs at all levels of the small and large intestine mucosa, whereas the ieMMC response was generally localized to infected segments of the gut with nematodes. The ieMMC hyperplasia associated with Treg deficiencies indicates that loss of some Treg functions contributes to ieMMC hyperplasia, most likely as part of a Th2-biased inflammatory response.

Tregs preferentially induce apoptosis of Th2 cells, placing the Th2 arm of the immune system under tighter Treg control than the Th1 arm.188 As a result, depletion of Tregs favors a Th2 immune response, which is characterized by increased numbers of IL4/IFNγ producing cells188 and ieMMCs. Functional Treg cells help establish immune tolerance to allergens via expression of the suppressor cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β.146 These are the cytokines most often implicated in Treg-mediated suppression of allergic asthma,151 with TGFβ1 reportedly suppressing IL-3-dependent MC proliferation and survival.23, 51, 166 Treg deficiencies due to naturally occurring mutations in the FOXP3 or in other genes that promote FOXP3 expression such as STAT5b are more susceptible to atopic diseases151 having a major Th2 component.15, 104 However, genetic background has a major impact on the effects TGF-β1 exerts on mast cell homeostasis in mice; TGF-β1 in Th1-biased C57BL/6 mice greatly reduces mast cell numbers, but increases them in Th2-prone 129/Sv mice.51 Similarly, although Treg depletion increases Th2 responses in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice to the same extent, the parasite resistance seen in Treg-depleted BALB/c mice is accompanied by increased IL-9 levels and MC degranulation, whereas in the susceptible C57BL/6 mice, neither IL-9 production nor MC degranulation are affected by Treg depletion.21, 22

Adding to the complexity of Th1 and Th2 responses in mucosal immunity, even the timing of Treg depletion in T. muris infections affects the outcome. We found that depletion of Tregs at early stages of infection reduced helminth burdens and the severity of mucosal lesions, and was associated with ieMMC hyperplasia. The release of tissue-derived cytokine signals at early time points is critical in the development of polarized Th2 immune responses in the mucosa.84 However, when we depleted Tregs later in infection, ieMMCs were absent and both parasite burden and immune pathology were increased in severity.167 Similar reductions in helminth burdens and lesion severity followed anti-CD25 antibody–mediated partial depletion of early Tregs, which increase T helper type 2 responses175 but under other conditions Treg depletion using anti-CD25 Ab exacerbated host pathology.32

GVHD

The more severe and acute onset GVHD lesions that develop in BALB/cJ recipients of C57BL/6J cells are most likely due to the production and secretion of Th1 cytokines (such as IL-2 and IFN-γ) by transplanted Th1-biased C57BL/6J cells, which would be expected to promote a Th1 response. Conversely, the milder and later onset mucosal inflammation (with ieMMC hyperplasia) that develops in C57BL/6J recipients of BALB/c spleen cells is most likely attributable to the well documented Th2 bias of BALB/cJ mice. The absence of ieMMCs in the severe acute onset GVHD lesions and their abundance in the milder later onset GVHD suggests that they may have a role in reducing immune mediated mucosal damage.

P19ARF null mice

The high prevalence of ieMMC hyperplasia we observed in p19ARF null mice was unexpected. The p14ARF (also called ARF tumor suppressor or ARF) and p16 (INK4a) proteins are both products of the CDKN2A locus and function as tumor suppressors.173, 174 Specifically, p14ARF protein helps prevent tumor formation by blocking the breakdown of the tumor suppressor protein p53. Increased tumor development is associated with a loss of function of INK4a, ARF, Rb, or p53.126 The equivalent protein in mice is p19ARF, and mice lacking p19ARF develop a wide range of tumors at relatively young ages.97 The patterns of diffuse ieMMC hyperplasia and normal tuft cell numbers that we observed in both large and small intestine mucosa are similar to those seen in our mice with Treg deficiencies. This suggests that p19ARF deficiency in mice affects mucosal immunological responses. There are reports suggesting ARF involvement in regulation of inflammatory responses.190, 191 Many genes involved in the innate immune response are expressed in p19ARF wild-type (but not null) tumors upon MYC inactivation, and p19ARF null mice showed reduced influx of macrophages into tumors.212 ARF is required for MYC to regulate the expression of genes involved in innate immune activation.100 Interestingly, CD8+ T cells in Cdkn2a−/− mice have been shown to produce significantly lower amounts of IL-10 and thus are more susceptible to 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis.216

Nude Mice

The presence of large numbers of ieMMCs in the inflamed intestinal mucosa of some nude mice was not expected because ieMMC hyperplasia is regarded to be a stereotypical Th2-regulated response in rodents, ruminants, and humans.94, 160, 163, 164 However, since the nude mouse can become “leaky” for extrathymic T cells with increasing age and in conventional housing, the presence of ieMMC hyperplasia in some nude mice is not entirely surprising or unprecedented. Early studies showing a lack of intestinal mast cell responses in T. spiralis infected athymic nude mice suggested that an intact thymus or T-cells are essential for the development of ieMMC hyperplasia,160 but later experiments by the same investigators showed that some T. spiralis infected athymic mice did actually mount a ieMMC response.161 Normal numbers of MMCs have been previously reported in the small intestinal mucosa of nude mice and nude rats, B rats, and a child with the Di George syndrome, in spite of the athymic status of the nude mice, the functionally deficient T cells in the B rats, and the vestigial nature of the thymus in the child (reviewed in130). These findings suggest that alternate pathways might exist for the induction of ieMMC hyperplasia in T-cell deficient animals. The recruitment and differentiation of ieMMCs is dependent on the release of TGFβ1 by enterocytes.114 TGFβ1 is secreted as a biologically inactive complex that has to be modified and activated by the epithelial integrin αvβ6.113 Therefore, any local conditions that could induce enterocytes to express two essential mediators (TGFβ1 and αvβ6) could theoretically provide an alternative T cell-independent pathway for the migration and differentiation of ieMMCs in the mucosa. The innate lymphoid cell (ILC) family may be involved in ieMMC hyperplasia in T cell deficient mice. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) have been reported in thymus deficient Foxn1nu/nu (nude) mice and other T cell deficient mice.158, 207 ILC2 cells can mount potent type 2 immune responses independently of Th2 cells, and respond to epithelial cytokines IL25 and IL33 by producing type 2 cytokines such as IL4, IL5, IL9 and IL13. In the gut this response is critical for anti-helminth immunity and in the pathogenesis of other intestinal diseases.76

Conclusion

We found that IHC provided the only means to reliably detect and differentiate lpMMCs in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded mouse intestines. Tuft cell and ieMMC (globule leukocyte) hyperplasia are typically associated with helminth infections. However, we found increased ieMMCs in both the small and large intestines of mice with various other conditions, with no apparent direct relationship between ieMMCs and tuft cells. We consistently found decreased mucosal inflammation and damage in associating with the presence of ieMMCs and more severe damage in their absence, suggesting that they might help reduce helminth-induced immunopathology. In addition to the known association of ieMMC hyperplasia with nematode infections, we found increased mucosal ieMMCs in other settings, including mice with Treg deficiencies, specific types of intestinal graft versus host disease, in otherwise unremarkable athymic nude mice, in a high proportion of p19ARF null mice.98 We did not detect any direct relationship between ieMMC and either lpMMC or tuft cell numbers in the intestinal mucosa. Much remains to be learned about of the differing functions of ieMMCs and lpMMCs in the intestinal mucosa, but an essential step in deciphering their roles in intestinal immune responses will be to consistently and accurately identify them in tissue sections. The application of sensitive IHC methods to accurately identify MMCs should prove useful in better defining the roles these cells play in mucosal immunology.

References

- 1.Akpavie SO, Pirie HM. The globule leucocyte: morphology, origin, function and fate, a review. Anatomia, histologia, embryologia 1989;18(1):87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alizadeh H, Murrell KD. The intestinal mast cell response to Trichinella spiralis infection in mast cell-deficient w/wv mice. The Journal of parasitology. 1984;70(5):767–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Artis D. New weapons in the war on worms: identification of putative mechanisms of immune-mediated expulsion of gastrointestinal nematodes. International journal for parasitology. 2006;36(6):723–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artis D, Villarino A, Silverman M, et al. The IL-27 receptor (WSX-1) is an inhibitor of innate and adaptive elements of type 2 immunity. Journal of immunology. 2004;173(9):5626–5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austen KF. The heterogeneity of mast cell populations and products. Hospital practice. 1984;19(9):135–139, 143-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bancroft AJ, McKenzie AN, Grencis RK. A critical role for IL-13 in resistance to intestinal nematode infection. Journal of immunology. 1998;160(7):3453–3461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bansemir AD, Sukhdeo MV. The food resource of adult Heligmosomoides polygyrus in the small intestine. The Journal of parasitology. 1994;80(1):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Befus AD, Pearce FL, Gauldie J, Horsewood P, Bienenstock J. Mucosal mast cells. I. Isolation and functional characteristics of rat intestinal mast cells. Journal of immunology. 1982;128(6):2475–2480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Befus D. Immunity in intestinal helminth infections: present concepts, future directions. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1986;80(5):735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Befus D. Intestinal mast cell polymorphism: new research directions and clinical implications. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 1986;5(4):517–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behnke J, Harris PD. Heligmosomoides bakeri: a new name for an old worm? Trends in parasitology. 2010;26(11):524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behnke JM, Wahid FN, Grencis RK, Else KJ, Ben-Smith AW, Goyal PK. Immunological relationships during primary infection with Heligmosomoides polygyrus (Nematospiroides dubius): downregulation of specific cytokine secretion (IL-9 and IL-10) correlates with poor mastocytosis and chronic survival of adult worms. Parasite immunology. 1993;15(7):415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell LV, Else KJ. Mechanisms of leucocyte recruitment to the inflamed large intestine: redundancy in integrin and addressin usage. Parasite immunology. 2008;30(3):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Smith A, Lammas DA, Behnke JM. The relative involvement of Th1 and Th2 associated immune responses in the expulsion of a primary infection of Heligmosomoides polygyrus in mice of differing response phenotype. Journal of helminthology. 2003;77(2):133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nature genetics. 2001;27(1):20–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betts CJ, Else KJ. Mast cells, eosinophils and antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity are not critical in resistance to Trichuris muris. Parasite immunology. 1999;21(1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bienenstock J, Befus AD, Denburg J, Goodacre R, Pearce F, Shanahan F. Mast cell heterogeneity. Monographs in allergy. 1983;18:124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bienenstock J, Befus AD, Pearce F, Denburg J, Goodacre R. Mast cell heterogeneity: derivation and function, with emphasis on the intestine. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1982;70(6):407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bischoff SC, Wedemeyer J, Herrmann A, et al. Quantitative assessment of intestinal eosinophils and mast cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Histopathology. 1996;28(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisset SA, Vlassoff A, Douch PG, Jonas WE, West CJ, Green RS. Nematode burdens and immunological responses following natural challenge in Romney lambs selectively bred for low or high faecal worm egg count. Veterinary parasitology. 1996;61(3–4):249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blankenhaus B, Klemm U, Eschbach ML, et al. Strongyloides ratti infection induces expansion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells that interfere with immune response and parasite clearance in BALB/c mice. Journal of immunology. 2011;186(7):4295–4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blankenhaus B, Reitz M, Brenz Y, et al. Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells delay expulsion of intestinal nematodes by suppression of IL-9-driven mast cell activation in BALB/c but not in C57BL/6 mice. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10(2):e1003913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broide DH, Wasserman SI, Alvaro-Gracia J, Zvaifler NJ, Firestein GS. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 selectively inhibits IL-3-dependent mast cell proliferation without affecting mast cell function or differentiation. Journal of immunology. 1989;143(5):1591–1597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cantin M, Veilleux R. Globule leukocytes and mast cells of the urinary tract in magnesium-deficient rats. A cytochemical and electron microscopic study. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1972;27(5):495–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr KE. Fine structure of crystalline inclusions in the globule leucocyte of the mouse intestine. Journal of anatomy. 1967;101(Pt 4):793–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carr KE, Whur P. Ultrastructure of globule leucocyte inclusions in the rat and mouse. Zeitschrift fur Zellforschung und mikroskopische Anatomie. 1968;86(2):153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caughey GH. Mast cell proteases as protective and inflammatory mediators. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2011;716:212–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen F, Liu Z, Wu W, et al. An essential role for TH2-type responses in limiting acute tissue damage during experimental helminth infection. Nature medicine. 2012;18(2):260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collan Y. Characteristics of nonepithelial cells in the epithelium of normal rat ileum. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. Supplement 1972;18:1–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craig SS, Schwartz LB. Tryptase and chymase, markers of distinct types of human mast cells. Immunologic research. 1989;8(2):130–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crowle PK, Reed ND. Rejection of the intestinal parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis by mast cell-deficient W/Wv anemic mice. Infection and immunity. 1981;33(1):54–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Elia R, Behnke JM, Bradley JE, Else KJ. Regulatory T cells: a role in the control of helminth-driven intestinal pathology and worm survival. Journal of immunology. 2009;182(4):2340–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Silva EZ, Jamur MC, Oliver C. Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2014;62(10):698–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawicki W, Marshall JS. New and emerging roles for mast cells in host defence. Current opinion in immunology. 2007;19(1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Winter BY, van den Wijngaard RM, de Jonge WJ. Intestinal mast cells in gut inflammation and motility disturbances. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1822(1):66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donaldson LE, Schmitt E, Huntley JF, Newlands GF, Grencis RK. A critical role for stem cell factor and c-kit in host protective immunity to an intestinal helminth. International immunology. 1996;8(4):559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Douch PG, Harrison GB, Elliott DC, Buchanan LL, Greer KS. Relationship of gastrointestinal histology and mucus antiparasite activity with the development of resistance to trichostrongyle infections in sheep. Veterinary parasitology. 1986;20(4):315–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dvorak AM, Monahan RA, Osage JE, Dickersin GR. Mast-cell degranulation in Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 1978;1(8062):498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrlich P. Beiträge zur Theorie und Praxis der histologischen Färbung. Leipzig University, Germany. 1878. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elliott DE, Metwali A, Leung J, et al. Colonization with Heligmosomoides polygyrus suppresses mucosal IL-17 production. Journal of immunology. 2008;181(4):2414–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott DE, Weinstock JV. Where are we on worms? Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2012;28(6):551–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Else KJ, Finkelman FD. Intestinal nematode parasites, cytokines and effector mechanisms. International journal for parasitology. 1998;28(8):1145–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Else KJ, Hultner L, Grencis RK. Cellular immune responses to the murine nematode parasite Trichuris muris. II. Differential induction of TH-cell subsets in resistant versus susceptible mice. Immunology. 1992;75(2):232–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enerback L. Mast cells in rat gastrointestinal mucosa. 2. Dye-binding and metachromatic properties. Acta pathologica et microbiologica Scandinavica. 1966;66(3):303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Enerback L. Mast cells in rat gastrointestinal mucosa. I. Effects of fixation. Acta pathologica et microbiologica Scandinavica. 1966;66(3):289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enerback L. The gut mucosal mast cell In: Edebo LB, Stendahl OI, eds. Monogr Allergy. Vol 17: Karger; 1981:222–232. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Enerback L. Mucosal mast cells in the rat and in man. International archives of allergy and applied immunology. 1987;82(3–4):249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Enerback L, Kolset SO, Kusche M, Hjerpe A, Lindahl U. Glycosaminoglycans in rat mucosal mast cells. The Biochemical journal. 1985;227(2):661–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faulkner H, Humphreys N, Renauld JC, Van Snick J, Grencis R. Interleukin-9 is involved in host protective immunity to intestinal nematode infection. European journal of immunology. 1997;27(10):2536–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferguson A, Cummins AG, Munro GH, Gibson S, Miller HR. Roles of mucosal mast cells in intestinal cell-mediated immunity. Annals of allergy. 1987;59(5 Pt 2):40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernando J, Faber TW, Pullen NA, et al. Genotype-dependent effects of TGF-beta1 on mast cell function: targeting the Stat5 pathway. Journal of immunology. 2013;191(9):4505–4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Filbey KJ, Grainger JR, Smith KA, et al. Innate and adaptive type 2 immune cell responses in genetically controlled resistance to intestinal helminth infection. Immunology and cell biology. 2014;92(5):436–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finkelman FD, Urban JF Jr. The other side of the coin: the protective role of the TH2 cytokines. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2001;107(5):772–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finlay CM, Walsh KP, Mills KH. Induction of regulatory cells by helminth parasites: exploitation for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Immunological reviews. 2014;259(1):206–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fleming JO, Isaak A, Lee JE, et al. Probiotic helminth administration in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 1 study. Multiple sclerosis. 2011;17(6):743–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleming JO, Weinstock JV. Clinical trials of helminth therapy in autoimmune diseases: rationale and findings. Parasite immunology. 2015;37(6):277–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Forbes EE, Groschwitz K, Abonia JP, et al. IL-9- and mast cell-mediated intestinal permeability predisposes to oral antigen hypersensitivity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205(4):897–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friend DS, Ghildyal N, Austen KF, Gurish MF, Matsumoto R, Stevens RL. Mast cells that reside at different locations in the jejunum of mice infected with Trichinella spiralis exhibit sequential changes in their granule ultrastructure and chymase phenotype. The Journal of cell biology. 1996;135(1):279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galli SJ. New insights into “the riddle of the mast cells”: microenvironmental regulation of mast cell development and phenotypic heterogeneity. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1990;62(1):5–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galli SJ, Grimbaldeston M, Tsai M. Immunomodulatory mast cells: negative, as well as positive, regulators of immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology 2008;8(6):478–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galli SJ, Starkl P, Marichal T, Tsai M. Mast cells and IgE in defense against venoms: Possible “good side” of allergy? Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galli SJ, Tsai M. Mast cells: versatile regulators of inflammation, tissue remodeling, host defense and homeostasis. Journal of dermatological science. 2008;49(1):7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galli SJ, Tsai M. Mast cells in allergy and infection: versatile effector and regulatory cells in innate and adaptive immunity. European journal of immunology. 2010;40(7):1843–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gamble HR, Zajac AM. Resistance of St. Croix lambs to Haemonchus contortus in experimentally and naturally acquired infections. Veterinary parasitology. 1992;41(3–4):211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gerbe F, Legraverend C, Jay P. The intestinal epithelium tuft cells: specification and function. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2012;69(17):2907–2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerbe F, Sidot E, Smyth DJ, et al. Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature. 2016;529(7585):226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Godfraind C, Louahed J, Faulkner H, et al. Intraepithelial infiltration by mast cells with both connective tissue-type and mucosal-type characteristics in gut, trachea, and kidneys of IL-9 transgenic mice. Journal of immunology. 1998;160(8):3989–3996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grainger JR, Smith KA, Hewitson JP, et al. Helminth secretions induce de novo T cell Foxp3 expression and regulatory function through the TGF-beta pathway. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207(11):2331–2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grimbaldeston MA, Chen CC, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tam SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant Kit W-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. The American journal of pathology. 2005;167(3):835–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grimbaldeston MA, Metz M, Yu M, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Effector and potential immunoregulatory roles of mast cells in IgE-associated acquired immune responses. Current opinion in immunology. 2006;18(6):751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]