Abstract

Unraveling how neural networks process and represent sensory information and how these cellular signals instruct behavioral output is a main goal in neuroscience. Two-photon activation of optogenetic actuators and calcium (Ca2+) imaging with genetically encoded indicators allow, respectively, the all-optical stimulation and readout of activity from genetically identified cell populations. However, these techniques locally expose the brain to high near-infrared light doses, raising the concern of light-induced adverse effects on the biology under study. Combining 2P imaging of Ca2+ transients in GCaMP6f-expressing cortical astrocytes and unbiased machine-based event detection, we demonstrate the subtle build-up of aberrant microdomain Ca2+ transients in the fine astroglial processes that depended on the average rather than peak laser power. Illumination conditions routinely being used in biological 2P microscopy (920-nm excitation, ∼100-fs, and ∼10 mW average power) increased the frequency of microdomain Ca2+ events but left their amplitude, area, and duration largely unchanged. Ca2+ transients in the otherwise silent soma were secondary to this peripheral hyperactivity that occurred without overt morphological damage. Continuous-wave (nonpulsed) 920-nm illumination at the same average power was as damaging as femtosecond pulses, unraveling the dominance of a heating-mediated damage mechanism. In an astrocyte-specific inositol 3-phosphate receptor type-2 knockout mouse, near-infrared light-induced Ca2+ microdomains persisted in the small processes, underpinning their resemblance to physiological inositol 3-phosphate receptor type-2-independent Ca2+ signals, whereas somatic hyperactivity was abolished. We conclude that, contrary to what has generally been believed in the field, shorter pulses and lower average power can help to alleviate damage and allow for longer recording windows at 920 nm.

Significance

Imaging the fine structure and function of the brain has become possible with two-photon microscopy that uses ultrashort pulsed infrared light for better tissue penetration. The high peak energy of these laser pulses has raised concerns about nonlinear photodamage resulting from multiphoton processes. Here, we show that not only the pulse energy but also the time-averaged laser power matters in a practical biological experiment. At wavelengths and with laser powers commonly used in current neuroscience, aberrant Ca2+ signaling occurs as a consequence of direct infrared light absorption, that is, heating. To counteract brain heating, we explore a strategy that uses even shorter, more energetic pulses but a lower time-averaged laser power to produce the same image quality.

Introduction

Two-photon (2P) excitation fluorescence microscopy (1) is the method of choice for imaging structural and functional dynamics in the intact brain (2, 3, 4). Addressing the role of genetically identified cell populations in a circuit-specific manner has become possible through the advent and improvement of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECIs) (5, 6, 7). Considerable efforts are being made to enhance the speed, spatial resolution and field-of-view of 2P Ca2+ imaging, but for a given GECI, the user has to trade off gains in one of these parameters against losses in others, unless the number of excitation spots and/or the average laser power per spot are increased.

2P fluorescence excitation requires high instantaneous peak intensities, which has prompted concerns about nonlinear photobleaching (8) and photodamage (9,10), resulting from excited-state absorption in the high-intensity focus. Several studies have established a steep intensity threshold for this nonlinear damage. However, from a (neuro-) physiologist’s standpoint, overt morphological tissue damage as much as irreversible alterations (like those apparent on ex vivo immunofluorescence) are a late, and probably too late, criterion for assessing biological damage. Therefore, we sought for a subtler and perhaps reversible indicator of altered physiology. We used the occurrence of aberrant, light-induced Ca2+ signals as a sensitive readout, similar to earlier studies on neurons (9, 10, 11). In the 2P microscopy field, average laser powers of the order of tens of mW per excitation spot are generally being considered harmless (11) and up to 250 mW have been reported safe in multispot excitation schemes (12). Yet, how different pulse parameters (pulse length, interpulse interval, and peak power) affect this damage threshold has remained controversial.

In the current work, we report on a photodamage that does not involve 2P absorption, affects physiological astrocytic Ca2+ signals, occurs upon 920-nm excitation at low mW powers, and likely involves a local, heating-mediated damage mechanism. Unbiased automated analysis of Ca2+ signals revealed a subtle but measurable build-up of spontaneous, microdomain Ca2+ activity in the fine processes of GCaMP6f-expressing cortical astrocytes during minute-long recordings routinely used for 2P brain imaging. Near-infrared (NIR) illumination initially just increased the frequency while only slightly affecting the amplitude and cellular-volume fraction encompassed by these Ca2+ transients. Their frequency increase occurred without detectable morphological damage. This build-up of aberrant Ca2+ signals was followed by large Ca2+ transients in the otherwise silent soma. Pausing acquisitions for 10 min stalled light-induced Ca2+ hyperactivity and restored a preillumination baseline activity. Longer, less energetic pulses and higher average power (resulting in the same signal) were equally if not more harmful. As pulse stretching did not reduce the photo-induced Ca2+ signals, as would have been expected for a nonlinear damage mechanism, we postulated a lower damage power exponent (m < 2) and consequently investigated a linear (i.e., heating-mediated) damage process. Consistent with a single-photon absorption process, we found that even nonpulsed, continuous-wave (CW) 920-nm illumination was equally damaging to small astrocyte processes as were fs pulses.

Taken together, our experiments demonstrate that one-photon NIR absorption, in addition to nonlinear damage, can be a major limiting factor in the now commonly used wavelength band above 900 nm. This has important consequences for imaging fluorescent proteins and protein-based functional indicators as well as for studies using NIR stimulation for optogenetic activation. The careful optimization of the pulse length together with a reduction in the average laser power better preserves the biology under study.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic mice

All experiments followed institutional (CNRS) and European Union guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Council Directive 2010/63/EU). For astrocyte Ca2+ imaging, we bred mice that selectively expressed the GECI GCaMP6f in astrocytes (Fig. 1; Fig. S1). For that, we crossed a floxed reporter mouse line expressing GCaMP6f in the ROSA26 locus (Ai95D; Rosa-CAG-LSL-GCaMP6f; JAX stock no. 028865; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (13) with an astrocyte-specific cre driver line Tg(Glast-CreERT2)45–72 (14). For Fig. 5, inositol 3-phosphate (IP3) receptor (IP3R) type-2 (IP3R2) knockout (KO) mice (15) were crossed into the GLAST-creERT2::Rosa-CAG-LSL-GCaMP6f line in two steps. This generated homozygous IP3R2-KO mice expressing GCaMP6f selectively in astrocytes. As a first step, heterozygous IP3R2-KO::GLAST-creERT2 mice and heterozygous IP3R2-KO::Rosa-CAG-LSL-GCaMP6f mice were generated. As a second step, these two lines were crossed to obtain homozygous IP3R2-KO mice expressing GCaMP6f selectively in astrocytes. The genotype (homozygous IP3R2-KO) was systematically verified by PCR on the day of the experiment. Cre recombinase activity was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), diluted in corn oil, between postnatal days (P)14 to P18.

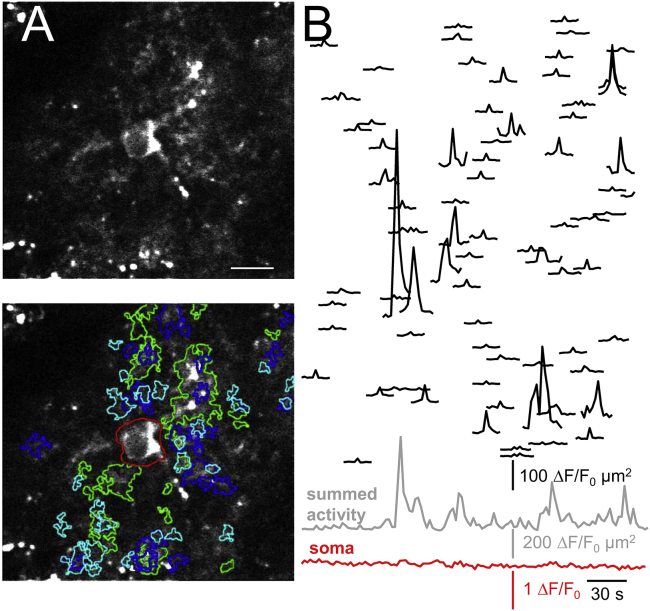

Figure 1.

Properties of spontaneous astrocyte Ca2+ signals. (A) Diffraction-limited 920-nm excited two-photon (2P) fluorescence image across a single equatorial plane of a GCaMP6f-expressing astrocyte in an acute mouse brain slice of the barrel cortex. Imaging depth ∼83 μm. Top: morphological overview from the time-average of 120 consecutive frames, taken at 0.5 Hz. Bottom: regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to the detected Ca2+ transients (color for better discrimination) are shown. Overlapping ROIs indicate activity occurring in the same area at different time points. Red, central ROI shows the soma. Scale bar, 10 μm (see Video S1). (B) Black traces represent area size-scaled fluorescence transients of spontaneous Ca2+ events (i.e., ΔF/F0 multiplied by the area of the corresponding ROI) ordered, from top to bottom, according to their distance to soma. See Fig. S2 and Materials and Methods for details on the detection algorithm. Bottom (gray): summed activity over all events in the astrocyte processes is shown. Red trace represents somatic activity. The soma was silent throughout the recording. To see this figure in color, go online.

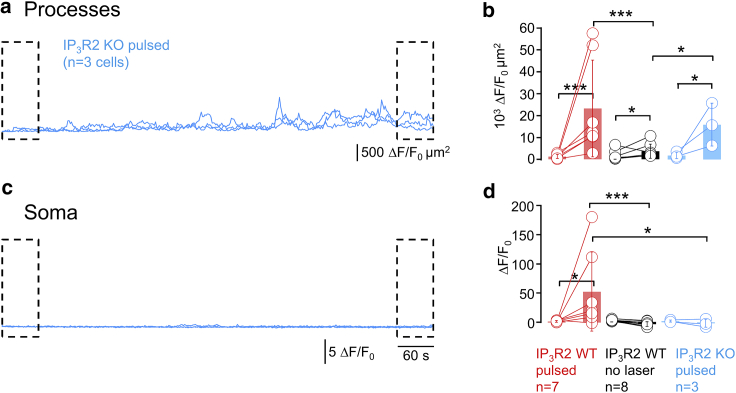

Figure 5.

Somatic but not peripheral Ca2+ hyperactivity is IP3R2 receptor dependent. (A) Cumulative Ca2+ activity in the astrocyte processes during a 12-min recording (920 nm, 90 fs, 0.5 Hz) of GCaMP6f-expressing astrocytes from IP3R2 KO mice shows a pronounced light-induced Ca2+ hyperactivity in the processes (n = 3 cells from two mice). (B) Shown is the comparison of cumulative activity in the processes of IP3R2 KO mice during the beginning, p1 (0–60 s) and the end of the recording, p3 (660–720 s) (p1 and p3 are the same as in in Fig. 4, light blue graphs, one-sided nonparametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney two-sample rank test). No significant difference is observed between either p1 or p3 between IP3R2 KO or WT mice (data from Fig. 4D), whereas the KO data during p3 is significantly different from the same period when the laser was shuttered (data from Fig. 4D), confirming that peripheral Ca2+ hyperactivity persisted in the absence of the IP3-mediated signaling pathways. In contrast, (C) soma of IP3R2 KO astrocytes are silent during the whole recording period in all cells. (D) In fact, somatic activity in IP3R2 KO mice is more similar to the WT astrocytes that were only imaged during p1 and p3 with the laser shuttered in between than to those that were exposed to continuous 2P excitation fluorescence imaging (cf., Fig. 4F). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.005, n.s., not significant. To see this figure in color, go online.

Acute brain slice recordings

P33–P46 mice were decapitated, and their heads were transferred to ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) NaCl 126, KCl 1.5, KH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 26, CaCl2 2, MgSO4 1.5, glucose 10, NaPyruvate 5, ascorbic acid 0.5, and L-glutathione 1, and bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. 350-μm thick coronal slices of the S1 barrel cortex were cut on a vibratome (HM 650V; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in ice-cold slicing solution, containing (in mM) potassium gluconate 130, KCl 15, EGTA 0.2, HEPES 20, glucose 20, NaPyruvate 5, ascorbic acid 0.5, L-glutathione 1, and AP-5 (50 μM), adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Slices were transferred for 1 min to a mannitol-based recovery solution at 33°C, containing (in mM) D-mannitol 225, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 26, CaCl2 0.8, MgCl2 8, glucose 20, NaPyruvate 5, ascorbic acid 0.5, and L-glutathione 1 (16). They were then incubated for 30 min in ACSF at 33°C. For recordings, the slices were placed in a ∼1 mL volume chamber and perfused at 4 mL/min with prewarmed ACSF. The final temperature in the bath was 31–34°C, measured with an electronic bath thermometer. We did not separately heat the large low-magnification, high-NA objective that hence acts as a heat sink. Unless otherwise stated, the recording solution did not contain tetrodotoxin (TTX). A small sliver harp with nylon wires glued to it maintained the slice stable in the perfused chamber during recording. Mechanically instable recordings were discarded.

Immunofluorescence

The selective expression of GCaMP6f in astrocytes as well as the fraction of cells expression the GECI were quantified in slices using standard immunofluorescence and epifluorescence or confocal microscopy (see Supporting Materials and Methods).

2P microscopy

Details of our homebuilt 2P microscope are published (17), and methods specific for this study are found in the companion article (E. Schmidt, M. van 't Hoff, M. Oheim, unpublished data). Briefly, the attenuated and expanded beam of a fs-pulsed laser (MaiTai HP; Spectra-Physics Newport, Mountain View, CA) was scanned (Yanus IV; TILL Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany) and focused with a low-magnification high-NA ×20/0.95w XLMPlanFluor dipping lens (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) (18). The mean laser power was measured in air after transmission through the objective using a Coherent FieldMate powermeter with PM10 measurement head. Pulse lengths were controlled with a motorized extracavity GDD compensation module (DeepSee; Spectra-Physics Newport) and measured in the sample plane by aid of an in-line autocorrelator with external measurement head (Carpe; Angewandte Physik und Elektronik, APE, Berlin, Germany). 2P fluorescence was excited at 920 nm (with 90- or 172-fs pulse length in the sample plane, respectively), extracted with a custom 2 mm-thick large-format dichroic (700DCXXR short pass; AHF Analysentechnik, Tübingen, Germany), transmitted laser light rejected with a 680 short-pass filter (Semrock, Rochester, NY), and the remaining fluorescence funnelled through a 6-mm core diameter liquid-light guide (Lumatec, Deisenhofen, Germany) to an external, nondescanned detector box (17). This detection optics is projective, not imaging, and it maintains the étendu for optimal collection of multiple scattered fluorescence photons (18). GCaMP6f fluorescence was detected in the green channel through an ET510/80 (Semrock) emission filter and 1-mm BG22 infrared (IR) blocking filter on a side-on R6357SELECT photomultiplier (Hamamatsu Photonics, Toyooka, Japan) with homebuilt amplifiers and electronics. For each cell, we acquired a time-lapse image series of 500 frames (at 0.5 Hz) from a single equatorial plane encompassing the soma at a diffraction-limited resolution. The pixel size in the specimen plane was 146 nm. Dwell time/pixel was 6.13 μs (⇔;163 kHz scan rate). Average laser powers in the recording plane were 17.3 ± 2.7 mW (mean ± SD) for 90-ms pulses, and astrocyte soma were located, on average, at 78 ± 14 μm below the slice surface. This power requirement was a consequence of the dim basal fluorescence of GCaMP6f. For comparison, <5 mW were required for imaging EGFP-expressing astrocytes in an Aldhl1-GFP-expressing mouse line at similar imaging depths (data not shown). Image sizes were slightly different from one cell to another, as a consequence of the variable in-plane morphology of the imaged astrocyte, with a mean and SD area of (4209 ± 590) μm2, typically some 70 μm by 70 μm.

Disruption of laser mode-locking

To compare the effects of 920-nm pulsed and CW illumination, the passive intracavity mode-locking of the MaiTai laser was hindered by narrowing the motorized tunable slit aperture inside the laser cavity via software control. The slit motor position was tuned from the initial 450 arbitrary units to 220 arbitrary units. Narrowing the slit resulted in a gradual pulse broadening that finally switched to CW operation (Video S1. Spontaneous Ca2+ Signals in a Murine Cortical Astrocyte Expressing GCaMP6f, Video S2. Increase of Spontaneous Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals during 2PEF Imaging, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material A). As expected, this disruption of mode-locking (dubbed “de-mode-locking” in the figures) was accompanied by a narrowing of the spectral width (Fig. S5 B), measured with a fiber-coupled spectrometer (CCS 100; Thorlabs, Newton, NJ). The resulting slightly asymmetric pulse spectrum provokes a slight shift in the output wavelength that we compensated for by setting the target wavelength to 933 nm, which eventually resulted in a pulse spectrum centered at 920 nm. The de-mode-locking via partial beam obstruction reduced the laser output power so that we compensated for the power loss by augmenting the acousto-optic modulator transmittance so as to keep the average power at the objective constant under fs-pulsed and CW conditions (Fig. S6). In addition to pulse-length and spectral measurements, we directly ascertained the loss of mode-locking by confirming the loss of 2P-excited fluorescence before experiments from a green fluorescent Chroma test slide (data not shown) before we imaged cells. During the “pump-probe” protocol (Fig. 4), we interleaved a pause of 30 s between all recording episodes (de-mode-locked, optimized pulses, and shutter closed) to allow for the wavelength shift as well as the narrowing/reopening of the intracavity slit and stabilization of the laser operation and output.

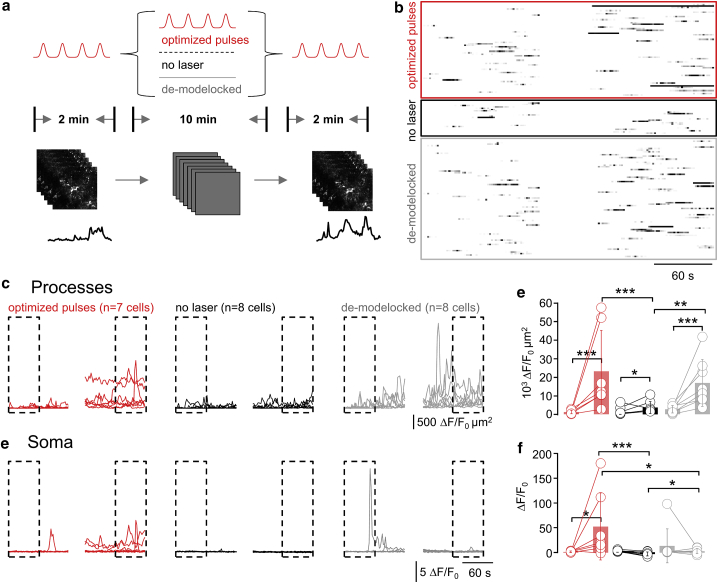

Figure 4.

Light-induced Ca2+ hyperactivity depends on total light dose, not the pulse energy. (A) Schematic representation of the experiment design is shown. Spontaneous Ca2+ transients were recorded during a 2-min control period to establish a baseline activity (p1; 920 nm, 90 fs, 0.5 Hz). Then, during 10 min, three different protocols were applied: 1) the cells were either imaged as in the preceding figures (with the same hyperactivity scenario as before), or 2) the laser was shuttered and the cells allowed to recover from the previous recording. In a third variant, 3) we disrupted the laser mode-locking to expose the cells to continuous-wave (CW) radiation with the same average power as during pulsed excitation (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S6). The respective impact of these different protocols on the astrocytic Ca2+ activity was read out in another 2-min recording (with the same parameters as p1). (B) Raster plots illustrate the outcome of the three different protocols. (C) Cumulative Ca2+ activity traces in the astrocyte processes during p1 and p3 are shown. (D) Statistical analysis of data was shown in (C). Shown are the activity increases for all conditions between the beginning of p1 (0–60 s) and end of p3 (660–720 s; one-sided nonparametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney two-sample rank test). Of note, the Ca2+ activity in the processes during p3 is indistinguishable between exposures to pulsed versus CW light, both of which are significantly higher than with the laser shuttered. All experiments started from initial activity levels during p1. n.s, not shown for clarity. (E) Shown are somatic ΔF/F0 traces for the three scenarios and statistical analysis in (F). For CW illumination, somatic activity is significantly higher in p3 compared to either no or pulsed excitation during p2, respectively. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.005, n.s., not significant. To see this figure in color, go online.

Quality control and data rejection

Given the tiny structures studied, micrometric lateral or axial slice movements can result in drift and defocus, respectively, that falsify the assignment of pixels to Ca2+ signals and hence adversely influence the event detection during the relatively long recordings. We therefore systematically verified the quality of each recording. To this end, we generated averages in the form of two “ministacks” of 60 frames each, at the beginning and end of the 500-frame recording, respectively. Their average-intensity projections were overlaid in red/green pseudocolor and inspected for movement and defocus by comparing the position and sharpness of fine morphological features. To exclude bias, the person validating the data was unaware of the recording condition and the occurrence (or not) of Ca2+ signals on the respective image stack. On this basis, we excluded 2/10 cells for 90-fs pulses and 2/9 cells for the longer 172-fs pluses (data shown in Figs. 1, 2, and 3; Figs. S3 and S4). For the de-mode-locking experiments, we rejected 4/12 cells; for the laser-shuttered ones, 6/14 cells; for pulsed 90-fs imaging, 3/10 cells; and for the IP3R2-Kos, 1/4 cells were excluded, respectively (data shown in Figs. 4 and 5; Fig. S6).

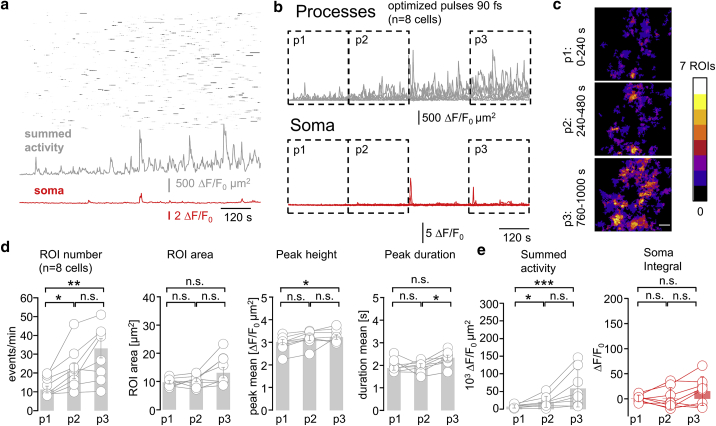

Figure 2.

2P excitation at 920 nm triggers a subtle but discernable Ca2+ hyperactivity. (A) Black shows raster plot of the data in Fig. 1B, along with its further evolution during a recording lasting more than 16 min (500 frames, 0.5 Hz). Gray represents an increase of the summed activity over all processes. Red shows that the initially silent soma becomes progressively active. (B) Shown are summed peripheral (gray) and somatic (red) activities under the same conditions as in (A) for n = 8 cells in N = 6 mice. Mean activity was quantified during periods p1: 0–240 s, p2: 240–480 s, p3: 760–1000 s, and boxed. (C) Shown is a pseudocolor overlay of the events detected during p1, p2, and p3 for the cell in (A). Ca2+ activity increasingly occurs at similar spatial locations during p2 and p3. Scale bars, 10 μm. (D) Shown are parameters characterizing Ca2+ transients during p1, p2, and p3. Bar plots show population mean ± SE, and symbols graph individual cells. Ca2+ microdomain frequency increases from p1 to p2 and between p1 and p3 (two-sided nonparametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney two-sample rank test). Light-induced Ca2+ signals resemble spontaneous Ca2+ microdomains, which makes them difficult to distinguish. (E) Gray shows a comparison of the summed activity in the astrocyte processes, i.e., integral of the traces shown in (B), reveals a net increase between p1 vs. p2 and p1 vs. p3. Red shows the somatic activity, corresponding to the red traces in (B), and remains significantly unchanged during all recording periods, although a trend to progressively higher activity is seen. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.005, n.s., not significant. To see this figure in color, go online.

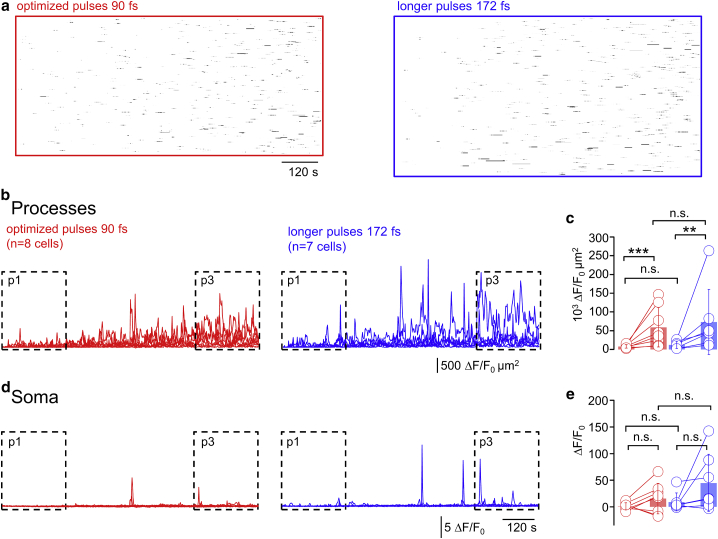

Figure 3.

Longer, less energetic pulses do not reduce light-evoked Ca2+ hyperactivity. (A) Right: raster plot of 920-nm light-induced Ca2+ hyperactivity as in Fig. 2A but for a different cell is shown. Pulses were carefully optimized as in the two previous figures to achieve the shortest possible pulses under the objective (see Materials and Methods), resulting in a 90-fs pulse length (sech2). See Video S2 for a recording of this cell. Left: shown is the same for a cell excited with 172-fs pulses, i.e., with lower peak power but higher average laser power to maintain a constant initial signal, i.e., 2/τ = const. (B) Red shows the summed activity as in Fig. 2B (n = 8 cells/six mice at 90 fs) and side-to-side comparison with summed activity upon 172-fs excitation (blue). (C) Ca2+ activities in p3 compared to p1 (defined as in Fig. 2B) increase (mean ± SE) for both 90-fs (red, same data as in Fig. 2E) and 172-fs pulses (blue, n = 7 cells/six mice) are shown. Activity was undistinguishable between short and long pulses for p1 (validating our experimental paradigm) but also during p3, i.e., contrary to what was expected for a highly nonlinear photodamage, no significant difference was found for different pulse energies (one-sided nonparametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney two-sample rank test). (D) Shown are somatic ΔF/F0 traces for 90-fs (red, corresponding to Fig. 2B) and 172-fs pulses (blue). (E) Statistical analysis showed that the somatic activity was indistinguishable between 90-fs (red, corresponding to Fig. 2E) and 172-fs pulses (blue), both during p1 and p3. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.005, n.s., not significant. To see this figure in color, go online.

Unbiased machine-based Ca2+ event detection

For analyzing spontaneous Ca2+ signals, we programmed an automated, user-supervised, event-based detection algorithm in ImageJ (Fiji distribution (19, 20, 21), see Fig. S2). As a first step, intensity background was removed by subtracting the mean intensity measured in a user-selected cell-free area. Noise outliers were removed by “outlier removal” filtering (radius 1, threshold for removal of outlier: 1500 cts above the median). As the pixels belonging to a region of interest (ROI) defining a Ca2+ transient on a given frame still displayed very heterogeneous intensities, we needed to spatially filter the data without losing information to permit automated ROI selection. However, a median filter removed smaller regions or disconnected regions, whereas an average/Gaussian filter increased noise variations. After careful inspection of the raw data, it became clear that the sought information is not only contained in the intensity value of individual pixels but in the density of pixels showing higher than baseline values in a given area. This is plausible because for two equally large ROIs (one devoid of, the other displaying a Ca2+ transient), shot noise can produce in the former ROI pixels having similar intensities than those corresponding to a (small) Ca2+ transient, but noise pixels will rarely be nearby and will rather be scattered randomly. Therefore, for segmenting ROIs, on the background-subtracted and outlier-removed images, all pixels >0 were set to 255 to give signal-containing pixels equal weight (Video S1. Spontaneous Ca2+ Signals in a Murine Cortical Astrocyte Expressing GCaMP6f, Video S2. Increase of Spontaneous Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals during 2PEF Imaging C). This now binary image mask was Gaussian filtered (σ = 2 px) to smooth the contours. At this stage, we still could not use a simple intensity-based thresholding approach to identify events. The reason is that the baseline (i.e., resting) fluorescence of the soma and of the large processes is similar, if not higher, than the peak intensity of Ca2+ events occurring in the fine processes (see solid arrowhead in Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods, Figs. S1–S6, and Table S1, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material D; compare fluorescence intensity of the soma and the Ca2+ event). The reason for this is obvious; because of their dimensions of the order of 100 nm or even less, the volume occupied by the fine processes fills only a fraction of the 2P excitation volume (∼1 fL = 1 μm3), which results in a lower fluorescence compared to the signal coming from the soma and large processes, for which the entire 2P excitation volume resides fully in a sea of fluorophores (Fig. 1). Instead of applying a uniform threshold, we first subtracted from each frame of the time-lapse recording the time-averaged fluorescence of the first 10 frames. This removed the bright structures that have a higher baseline fluorescence including the soma (see open arrowhead in Video S1. Spontaneous Ca2+ Signals in a Murine Cortical Astrocyte Expressing GCaMP6f, Video S2. Increase of Spontaneous Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals during 2PEF Imaging E), but it kept the active regions unchanged. From that, we could threshold the image stack.

Next, to selected the contours of the ROIs, we binarized each frame using as a threshold the mean intensity of all pixels having a fluorescence >0 on the first 10 frames plus three times its SD (Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods, Figs. S1–S6, and Table S1, Video S2. Increase of Spontaneous Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals during 2PEF Imaging F). On the resulting binary image, holes in ROIs were filled to unity. Additionally, to only keep activity in the processes, the somatic region was blanked to 0. Next, frame per frame, the contours of all regions >3 μm2 were automatically selected. As a Ca2+ transient typically extends over several frames and the contours change from one frame to another, a choice had to be made as to which of the time-dependent contours ROI(t) to retain. To avoid different ROIs on consecutive frames, we implemented a routine that kept only the biggest one, reasoning that this choice corresponded to the frame showing the peak of the Ca2+ event (an example is seen on Fig. S2 G, for the event identified on frame #87, similar ROIs related to the same transient are also detected on frames #83, #84, #85, #86, #88, and #89, respectively. The ROIs all spatially and temporally overlap with the ROI on frame #87.) Traces showing the evolution with the time of the Ca2+-dependent 2P fluorescence, ΔF/F0(t), were generated by taking the mean fluorescence of the finally chosen ROI. Here, F0 corresponds to the baseline fluorescence of the same region during the first 10 frames of the time-lapse recording that showed no activity (i.e., no “hot pixels” on the binary region map). The peak of the fluorescence transient defined the event time; the frames preceding or after the peak, for which five consecutive data points were dimmer than half the peak intensity, were chosen as the beginning and end, respectively, of that event. We adopted the five consecutive frame criterion to count rapid, double-peaked events as one.

After this fully automated choice of ROIs and readout of Ca2+-dependent fluorescence transients, a user-controlled validation step was interleaved. For each event, the detected ROI contour was automatically superposed on the corresponding raw data image frame (to visually confirm the Ca2+ elevation) and on the temporally averaged stack (giving an idea of the cell morphology and to confirm its intracellular localization), and the corresponding ΔF/F0 trace was displayed for visual inspection. Artifacts from bright and almost stationary bright spots (marked asterisk in Fig. S2 B) that could result from lipofuscin-rich granules (22) or mitochondrial autofluorescence, as well as slight movement artifacts, were easily discernible from “true” Ca2+ transients on the basis of their different morphology and the different temporal profile of the ΔF/F0 trace. Using this procedure, we excluded 1.3% of all detected ROIs, and we observed no significant differences among the different experimental conditions, validating the robustness of our procedure (nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test). Finally, for the confirmed ROIs, ΔF/F0(t) traces and the extracted parameters were automatically tabulated, and the ROIs were overlaid on the original time-lapse image stack (background and outliers removed).

The traces, the ROI area and distance from soma (defined by their centroid distance), and the baseline fluorescence, start, peak, and end time points of each Ca2+ event were passed on to IGOR Pro (Version 6.3; Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) for further analysis. For data compression, only a small section of the trace around the Ca2+ event was kept (see Fig. S2, H and I). Finally, all ΔF/F0 traces were weighed with their respective ROI area, following the rationale that a larger active area corresponds to a larger Ca2+ release or influx and hence should manifest as a larger level of activity compared with a smaller otherwise identical active region (Fig. S2 J).

For statistical analysis between different experimental conditions, we analyzed each cell separately, i.e., we did not pool Ca2+ events from different cells in a given condition. We deliberately made this choice to be able to detect heterogeneity in the cells’ baseline activity and responses to illumination and to avoid that a single cell having a high baseline activity or showing a big increase in Ca2+ events in illumination could bias the comparison.

The somatic ROI was selected in ImageJ, and the corresponding intensity trace was systematically analyzed and stored, independent of whether Ca2+ activity was observed or not. Somatic ΔF/F0(t) traces were generated in IGOR Pro in a two-step process. In the first step, the algorithm searched for the consecutive five-frame segment that has the lowest SD on the initial 60 frames of the recording (the rationale being that this segment contained no Ca2+ events). We used this segment to calculate F0(I) and normalize the fluorescence trace as dF/F0(I). Using this F0(I), candidate somatic Ca2+ transients occurring on the same initial trace segment were detected (using the F0(I) + 3 SD criterion). Then, in a second step, a refined baseline estimate was generated from only those data points on which no peaks had been detected. This new value, F0(II), was used to calculate the somatic ΔF/F0(II) trace.

For the comparison shown in Fig. S3 B, a single ROI compassing the entire neuropil was selected by inversion of the previously identified somatic ROI. The mean intensity in the processes was extracted from a median-filtered (0.5-px radius) image stack (after removal of background and outliers as described before). The traces were then normalized and plotted as ΔF/F0, using the same two-step procedure as described above for the soma. The semiautomated program for Ca2+ event detection in ImageJ as well as the IGOR Pro scripts are available upon request.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were run in IGOR Pro. Data sets were compared using a nonparametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney two-sample rank test. For data sets with more than two conditions, a group test (nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2 approximation for the p-value) was performed first. Significance levels are marked in the graphs using ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.005, and n.s., not significant.

Results

Spontaneous astrocyte Ca2+ activity increases during two-photon recordings

2P imaging upon 920-nm excitation revealed a plethora of asynchronous and spatially confined Ca2+ signals (Fig. 1; Video S1) in the barrel cortex of adult mice (P33–P46) sparsely expressing GCaMP6f (23) in a subset of astrocytes (Fig. 1 A; Fig. S1). As observed by other laboratories, these microdomain Ca2+ signals did neither require neuronal nor direct astrocytic stimulation, and they persisted when blocking neuronal action potentials with TTX (1 μM) (see Discussion).

Diffraction-limited two-photon imaging at 0.5 Hz of an astrocyte expressing GCaMP6f in the S1 barrel cortex of an acute mouse brain slice. Analysis of this cell is shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 A Highly localized, spontaneous, asynchronous microdomain Ca2+-signals can be seen throughout the entire neuropil. The raw-data has only been median filtered (0.5 px) after background and outlier removal (as described in the Supporting Materials and Methods) and is displayed using a "fire" lookup table (LUT). The video is superimposed on the time-averaged fluorescence (shown in grey value) over the 1st 120 frames to have visual morphological landmarks. The video shows a 4-min recording at 25 fps (i.e., 50 times faster than original). Scale bar, 10 μm.

We acquired a time-lapse image series from a single equatorial plane encompassing the soma. We used a sawtooth raster scan with 163 kHz pixel rate and 0.5 Hz frame rate. Given the tiny dimensions of astrocyte processes, we Nyquist sampled (Δxy < PSFxy/2) at a pixel size of Δxy = 146 nm/px to maintain diffraction-limited spatial resolution (B < fs/2, where B is the bandwidth, fs the spatial frequency, and PSFxy is the lateral extent (FWHM) of the point spread function). Regions of elevated Ca2+ (Fig. 1 A, bottom) and their corresponding Ca2+ transient waveforms (Fig. 1 B, top) were extracted by an unbiased machine-based detection procedure (see Fig. S2). The “summed activity” trace indicative of the cumulative activity in the processes was dominated by a large number of small Ca2+ transients and a few large events, and it was otherwise flat as expected for a predominantly localized, asynchronous Ca2+ activity. The soma showed little, if any, spontaneous activity during the first 4 min of recording. On average, Ca2+ transients were rare (11.25 ± 1.76 events/min), short lived (1.90 ± 0.10 s duration), and of small amplitude (ΔF/F0 = 3.02 ± 0.12), and they were confined to tiny subregions of individual astrocyte branches (mean area, 9.26 ± 0.52 μm2 vs. 3969 ± 302 μm2 total astrocyte area, i.e., individual events occupied ∼0.2% of the surface area; mean ± SEM for eight cells during 4-min recording). These microdomain Ca2+ signals are very similar to those reported by others (24, 25, 26, 27).

Raster plots on which we ordered active regions according to their distance-to-soma revealed Ca2+ transients throughout the neuropil with no obvious localization preference. However, when we extended the recording duration beyond the initial 4 min, we recognized a first subtle and then increasingly pronounced Ca2+ hyperactivity in the fine processes (Fig. 2 A, top). This hyperactivity was also seen as a rise of the “summed activity” trace that measures the cumulative activity within the processes (Fig. 2 A, bottom, gray trace). Somatic Ca2+ hyperactivity was observed secondary to the photo-induced signal triggered in the cell’s periphery (Fig. 2 B, bottom, red trace). Also, with increasing recording time, astrocytic microdomain Ca2+ signals occurred repeatedly within the same subcellular domains (Fig. 2 C). Nevertheless, events remained initially relatively stereotyped in terms of their area, peak amplitude, and duration, but their frequency almost doubled (×1.87) when comparing early recording periods (p1, 0–4 min) with later ones (p2, 4–8 min). After 16 min of continuous recording, microdomain Ca2+ transients in the processes tripled in frequency and displayed a 40% increase in dF/F0 amplitude compared with the beginning (p1) (Fig. 2 D). Other parameters remained stable, indicating that photodamage merely triggered more events. We conclude that both event frequency (×2.94) and summed activity (×7.5) of the peripheral astrocyte Ca2+ activity are bona fide markers for light-induced Ca2+ hyperactivity. At the macroscopic level, longer recordings produced a net increase in somatic Ca2+ activity (×14.5, p3 vs. p1, Fig. 3 E and Video S2). Aberrant Ca2+ signals occurred in the absence of visible morphological damage, and mice expressing EGFP rather than GCaMP6f in an astrocyte-specific manner showed no detectable change (E. Schmidt, M. van 't Hoff, M. Oheim, unpublished data). Similar Ca2+ hyperactivity was observed in astrocytes expressing GCaMP3 (28), an earlier GECI displaying a higher basal fluorescence but reduced ΔF/F0 amplitude (29), excluding a GCaMP6f-specific effect (data not shown).

Diffraction-limited two-photon imaging at 0.5 Hz of an astrocyte expressing GCaMP6f in the S1 barrel cortex of an acute mouse brain slice as in Video S1, but with much longer recording time (16.3 min, 500 frames). With increasing recording time, the microdomain Ca2+ activity in the fine processes is increasing in frequency, and an aberrant activity of the otherwise silent soma can been seen towards the end of the recording. The original data has been median filtered (0.5 px) after background and outlier removal (as described in the Supporting Materials and Methods) and is shown with a "fire" LUT superimposed with a morphological image obtained by averaging the 1st 120 frames (grey scale LUT). This cell is corresponding to the one shown in the raster plot in Fig. 3 A. The video is shown at 25 fps (i.e., 50-times faster than the original). Scale bar, 10 μm.

The Ca2+ signal obtained when lumping together the entire neuropil to one single ROI mirrored the evolution with time of the summed activity of all individual detected events in the cell periphery (Fig. S3). Thus, at least as far as aberrant Ca2+ signaling is concerned, the fine processes behave as a single “compartment,” although they are highly branched and compartmentalized into a tortuous and diffusionally segregated volume. The soma behaves differently. Whatever the mechanism, damage initiation seems to be local.

Taken together, these first results demonstrate the vulnerability of small astrocyte processes to the exposure with pulsed NIR light at powers common to typical biological 2P microscopy. Laser powers of tens of mW routinely used in the literature trigger astroglial Ca2+ hyperactivity detectable in both processes and soma. Intriguingly, the illumination-induced Ca2+ transients initially differ little from their “physiological” counterparts but do differ in their frequency. As a first approximation, a simple “center versus surround” analysis provides a straightforward readout of aberrant light-induced Ca2+ activity in the soma and processes, respectively.

Pulse stretching does not reduce photodamage

For a given fluorophore, microscope, and signal, nonlinear photodamage can potentially be reduced by modifying either the pulse frequency f or duration τ and adjusting the average laser power accordingly. Keeping, respectively, f = const. or /τ2 = const. will maintain a constant signal. Longer pulses will hence reduce the pulse energy but require higher .

However, whether shorter or longer pulses are per se better for biological 2P imaging has been a matter of debate. The outcome depends on whether photobleaching and photodamage increase more or less rapidly with than the signal. Longer pulses will be neutral if damage scales with a power exponent m (i.e., m) of two, like 2P-excited fluorescence (9), whereas pulse stretching will be beneficial if higher-order photodamage (m > 2) dominates (10). Conversely, longer pulses will exacerbate damage processes having a m < 2, e.g., when one-photon absorbers are present (30) or if tissue heating occurs (31).

We next directly compared Ca2+ transients upon 920-nm excitation with 90-fs (as before) vs. 172-fs pulses. We had obtained 90-fs pulses by a careful optimization of the excitation optical path and an optimal prechirping in a wavelength- and objective-dependent manner so as to attain the shortest possible pulses in the sample plane. 172-fs pulses correspond to the standard “midline” manufacturer tuning of the DeepSee pulse compressor at 920 nm (see Supporting Materials and Methods; E. Schmidt, M. van 't Hoff, M. Oheim, unpublished data).

Unlike what would be expected for a nonlinear photodamage mechanism, longer pulses and higher laser power did not reduce aberrant Ca2+ signals (Fig. 3 A). In the experiments with 172-fs pulse length, we increased by a factor of 1.26 ± 0.06 compared with 90-fs pulses so that astrocytes had an equal initial GCaMP6f signal for either pulse length (see Supporting Materials and Methods and Fig. S4 for data of the individual cells). To exclude bias, we also alternated the sequence of short and long pulses so that half of the cells were imaged first to 90- and then to 172-fs pulses and vice versa for the other half. Upon excitation with 172-fs pulses, light-induced local Ca2+ signals were readily detectable in the astrocyte processes (Fig. 3 B), and somatic activation prevailed (Fig. 3 D). Quantifying the activity during the initial (p1) and terminal 4-min segments (p3) revealed by and large similar results for 172- and 90-fs pulses in the processes (cumulative activity increased ×6.0 vs. ×7.5, p1 vs. p3, Fig. 3 C). The overall somatic activity in p3 was not significantly different between both pulse lengths (Fig. 3 E), but somatic Ca2+ transients arrived earlier and were of larger amplitude at 172-fs than with the shorter pulses. Our results exclude a nonlinear photodamage as a mechanism for triggering aberrant astrocyte Ca2+ activity.

Equal-power CW illumination at 920-nm is as damaging as fs pulses

How can we explain that stretched pulses and higher peak powers are not more damaging? We hypothesized that, contrary to common belief, in the 100-fs and 920-nm excitation regime used for most fluorescent proteins like GCaMP, NIR photodamage is not dominated by highly nonlinear processes like excited-state absorption, absorption from the triplet state, or indirect effects that occur via reactive oxygen species production through mitochondrial two- and three-photon absorption or lipid oxidation but rather through direct NIR absorption. This is plausible because both water and lipid absorption increase by more than one order of magnitude between 800 and 900 nm (Fig. S5), and so does the risk of focal heating (31,32). Thus, unlike at the shorter wavelengths (700–800 nm) (33) that have traditionally been used for 2P excitation of dyes and small chemical indicators, the longer wavelengths that optimally excite fluorescent proteins and optogenetic activators and that are now commonly used in biological 2P microscopy might result in a significantly higher absorption and a local heat production.

A simple, testable prediction for a one-photon-mediated damage process is that depositing the same average power with a CW 920-nm laser (i.e., no pulsing) should be equally damaging as pulsed illumination with 2P fluorescence excitation. This is what we tested next after having ascertained the effectiveness of a software-based disruption of mode-locking of our Ti:Sapphire laser (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S6, A and B).

To permit a direct comparison, we designed a “pump-probe” experiment, in which we first imaged GCaMP6f-expressing astrocytes during 2 min with 90-fs pulses to establish a baseline activity for each cell. We then pursued during 10 more minutes with either pulsed or CW illumination (at the same ). As no fluorescence is excited when pulsing is disrupted, we read out the resulting Ca2+ activity during another 2-min “probe” period with pulsed excitation at the end of each recording. In a third variant (negative control), we simply shuttered the laser during the 10-min interval to allow the cells to recover before reading out the activity again in the terminal 2-min period (Fig. 4 A). For each cell, we graphed raster (Fig. 4 B) and cumulative activity plots (Fig. 4, C and E) similar to the earlier figures.

As before (cf., Figs. 2 and 3), ongoing fs-pulsed illumination triggered synchronized peripheral Ca2+ activity (Fig. 4 D) as well as somatic Ca2+ signals (Fig. 4 F). As predicted for a linear damage mechanism, CW illumination produced an amount of peripheral Ca2+ hyperactivity that was indistinguishable from pulsed excitation (Fig. 4, D and F, gray traces). Shuttering the laser between acquisitions virtually abolished this light-induced activity, indicating that the total light dose, not a once triggered and then irreversible progressing damage cascade, produced the aberrant Ca2+ signals (Fig. 4, D and F, black traces). Interestingly, and very different from the behavior of the astrocyte processes, CW illumination did not produce measurable somatic hyperactivity, suggesting that some structure or organelle predominantly located in the cell body can be sensitized by fs-pulsed but not continuous NIR illumination (Fig. 4 F). Together, our data provide compelling evidence for laser-induced one-photon damage being a source of peripheral astrocyte Ca2+ hyperactivity.

Somatic but not peripheral photodamage is IP3R mediated

What is the reason for the different damage mechanisms in the processes and soma? Perhaps reactive oxygen species affect Ca2+ handling by oxidation of the IP3R and sensitization of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release to promote perisomatic Ca2+ oscillations, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (34), and release (35). As the IP3R type-2 (IP3R2) is thought to be the major, if not only, IP3R expressed in astrocytes (36), we took advantage of an available IP3R2 KO mouse strain (15) to breed mice expressing GGCaMP6f in astrocytes devoid of IP3R2. Homozygous mice allowed us to test if IP3R sensitization was involved in mediating the somatic damage. As spontaneous Ca2+ signals persist in the processes in IP3R2-KO mice (37), we speculated that imaging-evoked somatic and peripheral Ca2+ signals could be distinguished through their IP3R2 dependence. As before, we ascertained for all experiments equal (Video S1. Spontaneous Ca2+ Signals in a Murine Cortical Astrocyte Expressing GCaMP6f, Video S2. Increase of Spontaneous Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals during 2PEF Imaging C) and equal mean GCaMP6f fluorescence at the beginning of the recordings (Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods, Figs. S1–S6, and Table S1, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material D).

Time-lapse 2P imaging of spontaneous Ca2+ activity in GCaMP6f-expressing astrocytes in slices of IP3R2-KO mice produced heat-induced microdomain Ca2+ transients in the cell periphery much as in the wild-type (WT) (Fig. 5 A). In stark contrast, the somatic Ca2+ hyperactivity was abolished (Fig. 5 C). Statistical analysis of the initial and terminal 1-min segments confirmed light-induced Ca2+ activity in the processes of astrocytes from IP3R2-KO mice (blue on Fig. 5 B). This increase was significant, both compared with the beginning of the same recording and with respect to the second period in WT mice when shuttering the laser (data reproduced from Fig. 4 D). However, different from WT mice, the same robust peripheral Ca2+ hyperactivity failed to trigger somatic responses in KO mice, confirming the involvement of perisomatic but not peripheral IP3R in the build-up of somatic light-induced Ca2+ transients.

Discussion

We used state-of-the art methods to image and analyze microdomain Ca2+ signals in cortical astrocytes to show that 1) 2P imaging under conditions usually considered noninvasive led to an increase in spontaneous astrocyte Ca2+ activity; 2) at constant signal (2/τ = const.), stretched pulses and a correspondingly increased average power failed to reduce this light-induced hyperactivity, excluding damage mechanisms with a power exponent m > 2; 3) 920-nm nonpulsed (CW) excitation at the same evoked aberrant microdomain Ca2+ signals in astrocyte processes with comparable efficiency than pulsed excitation, confirming a one-photon absorption mechanism; and 4) genetic ablation of the major astroglial IP3R abolished somatic Ca2+ transients, but it did not affect the heat-mediated hyperactivity in the fine processes, pointing to different damage mechanisms in the cell body and periphery.

Irreversible photodestruction or reversible modification of Ca2+ homeostasis

Our data show an increase in the spontaneous activity in astrocytes subsequent to minute-long exposures of pulsed and CW 920-nm light (Figs. 2, 3, and 4). When limiting the initial exposure (60 frames over 2 min acquired at diffraction-limited resolution and 159 kHz scan rate), this light-induced hyperactivity was reversible over a 10–12-min recovery window (Fig. 4, C and E, middle). Longer recordings led to permanently increased GCaMP fluorescence in the scanned region, to increased spiking, and eventually, to an uncontrolled build-up of Ca2+ transients and increase in resting Ca2+. This pathological hyperactivity is clearly prohibitive for studying the subtleties of Ca2+ microdomain signaling, and we consider a subtle deviation from unperturbed baseline activity as sufficiently invasive for discarding such recordings. The transient alterations observed in astrocyte Ca2+ homeostasis are reminiscent of the illumination-induced changes in neuronal firing rates, and they constitute a finer readout of light-induced adverse effects than those picked up by immunofluorescently monitored activation of astrocytic or microglial markers, heat shock protein, or activated caspase-3 16 h after a 20-min illumination episode at high laser power (>250 mW) (31).

Brain heating as a damage mechanism

Heating was considered as a possible damage mechanism even before the advent of the 2P microscope (38). Sheppard predicted permissive delivered to a single excitation spot around 35 and 100 mW for stationary illumination and fast scanning, respectively. These values seem optimistic relative to reported experimental damage thresholds that are closer to 10 mW in single-spot nonresonant scanning geometries (9, 10, 11). Comparing fs versus ps pulses, Schönle and Hell judged focal heating irrelevant at 750–800 nm (the then dominant spectral window for exciting small-molecule chemical indicators), but neither did they use a biological readout, nor is it clear if small cellular compartments or subcellular organelles would resist to the predicted 0.5–3°C-change calculated by their model (33). On the other extreme, König and co-workers reported that visually detectable morphological damage of unlabeled cultured cells exposed to fs and ps pulses (at 780 nm, 60-μs pixel dwell time, NA 1.3) followed an approximate 2/τ law, suggesting a power exponent close to m = 2 (30). Subtler forms of photodamage than visible destruction were not assessed in that study. At longer wavelengths, Macias-Romero et al. estimated a 1–5°C increase in the focus of a 1035-nm laser beam (80 MHz, 1.1 NA) in water for pixel dwell times <10 μs (39), and the authors argued in favor of wide-field illumination and low-repetition rate 2P imaging to mitigate thermal damage. Using the temperature-dependent Stokes shift of Laurdan, a 1°C/100 mW change was measured for a CW 1064-nm trapping beam in the 20- to 200-mW regime (40). Along the same lines, Schmidt and co-workers predicted a temperature rise around 5°C/100 mW for various IR trapping beams based on a model taking into account light absorption in the neighborhood of the focus, outward heat flow and heat sinking by the glass surfaces of the sample chamber (41). A ΔT of a similar order of magnitude (1.8°C/100 mW) was measured with thermocouple probes and quantum-dot nanothermometers upon 2P single-spot scanning in the neocortex of awake or anesthetized mice, in vivo, and > 250 mW produced irreversible thermal destructions (31). Recently, the Emiliani lab modeled and measured 2P-induced heating to predict bounds for safe conditions of spiral scan and digital holography photoactivation. They predicted a 2°C temperature rise produced by a 3-ms illumination with 100 holographic spots at the photostimulation conditions necessary to evoke an action potential in vivo (42).

In this broader context, our results underpin the relevance of thermal damage for two-photon imaging in the biologically important spectral window around 920 nm and call for a necessary degree of caution when designing and interpreting experiments using 2P microscopy and photostimulation. Wavelengths above 900 nm and in the μm regime are commonly being used for the two- and three-photon excitation of fluorescent proteins, GECIs, and for the optogenetic activation of opsin-expressing cells. NIR light at these wavelengths is potentially more invasive than previously thought, particularly when imaging at high spatiotemporal duty cycles or when using multiple-spot schemes that increase the total power deposit in tissue.

As thermal effects rely on the accumulation and dissipation of energy, they depend on λ and but also on other parameters like the imaging depth, the precise tissue geometry (culture, slice, in vivo), the scanning parameters, and the pulse frequency and shape. Moreover, the heat deposit will be additive or even supralinear in multispot, line illumination, and holographic illumination schemes (43) and when sampling with high spatial and temporal frequencies because nearby spots and high duty cycles will further intensify the heat that cannot dissipate into neighboring colder tissue volumes. On the other hand, external factors like brain cooling due to a cranial window (44), a room-temperature water dipping objective, or perfusion with temperature-controlled ACSF might contribute to equilibrating temperature gradients, at least for near-surface imaging.

At a fixed pulse length, we expect lower pulse repetition rates, shorter pixel dwell times, and rescanning (i.e., temporal averaging on a μs timescale) (45) to be beneficial. In view of thermal diffusion rates of ∼1 μm2/μs, random-access scanning schemes in which neighboring pixels are excited in a spatially interspersed manner rather than sequentially scanned will favor the dissipation of locally generated heat. An overall low overall duty cycle (i.e., the recording from multiple, distant, and small ROIs rather than from full frames or the use of short bursts of acquisitions taken at high frequency rather than continuous streaming of images (31)) should be beneficial to mitigate build-up of thermal damage. Random-access scanning (46, 47, 48) will be particularly useful in applications in which dense spatiotemporal sampling is indispensable like when imaging dendritic spines, astrocyte processes, or in applications of 2P stimulated emission depletion microscopy that inevitably goes along with even higher spatial frequency sampling.

Linear versus higher-order damage

Our work alerts the biological microscopist to the importance of other damage mechanisms that coexist with localized nonlinear photodamage (10,49) that is fairly well described in the literature. Of note, one has to distinguish between linear damage mechanisms in which (whatever observable is used for quantifying damage) the measured damage depends linearly on and one-photon mediated damage, which must not necessarily be linear. For example, photodamage by blue visible light or ultraviolet is typically nonlinear, e.g., when reducing equivalents are overwhelmed by radical production. We here show that NIR light-induced Ca2+ hyperactivity depends on the average rather than peak power, thereby identifying a one-photon-mediated process. However, just because damage does not require two-photon excitation, it does not follow that it is linear, and we did not establish a linear power law.

The simplest conclusion from our results is that photo-induced astrocytes microdomains are produced by a heating-mediated mechanism. Our work therefore calls for some prudence in the ongoing quest for ever-longer wavelength IR-excited and red-shifted probes for deep tissue imaging because both water and lipid absorption (μa) continue to increase at longer wavelengths. On the other hand, as tissue scattering (μs) is reduced at these wavelengths, the choice of the optimal fluorophore and excitation wavelength windows will be a compromise between absorption and scattering (50,51).

Thermal damage is a particular concern for deep tissue imaging because compensating for the exponential excitation losses with increasing depth will expose the tissue surface to very high laser powers that, even unfocused, will be harmful because of surface heat generation. On the other hand, at moderate imaging depths in vivo, the perplexing situation can arise that surface cooling dominates so that the largest temperature increase will be measured beneath the focal plane (31). Therefore, once again, the precise outcome will depend on the average power, wavelength, and experimental geometry.

Somatic Ca2+ signals are a sensitive readout for damage

Although somatic Ca2+ transients have been used as a proxy for astrocyte activity, ≥90% of spontaneous Ca2+ activity occurs in the cell periphery (24,27,43,52,53). We find (Figs. 1 and 2) that in cortical slices, astrocyte somata were mostly silent under conditions of 2P imaging that preserve physiological Ca2+ signaling. Somatic Ca2+ signals were sparse, and this blocks, both in experiments with 1 μM TTX in the bath and without neuronal action potential, making their occurrence a sensitive and facile readout for imaging-related damage.

Fine astrocytic processes have temperature-dependent calcium dynamics

In our experiments, aberrant somatic Ca2+ were systematically secondary to peripheral activation. Although we cannot exclude that only the small compartments are sensitive to focal heating and somatic activation is the pure result of a feed-forward damage propagation and integration, light-induced somatic Ca2+ transients clearly required IP3-mediated mechanisms (Fig. 5), perhaps via the sensitization of IP3Rs or the integration of Ca2+ activity from different astrocyte branches via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release mechanisms. In the cell periphery with its large membrane/cytosol ratio and tiny process volumes compared to the 2P focal volume (Fig. 1), other mechanisms seem to prevail. Candidates are channels with thermosensitive gating in the physiological temperature range like TRPV3 (54), STIM-1 (55), or a number of voltage-gated channels (56). Temperature variations around 37°C also sensitize to diverse stimuli triggering channel opening TRPV4 channels that are expressed in roughly 1/3 of astrocytes (57,58). Other Ca2+ influx pathways potentially targeted by NIR illumination are the plasma membrane sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) and TRPM2 (59), the latter regulated by oxidative stress. Alternatively, heat-induced pore formation or lipid rearrangements and plasma membrane perforation and/or of the membranes of Ca2+ stores could mediate microdomain Ca2+ hyperactivity, but it would seem unlikely that this type of damage will result in the same stereotyped waveform of Ca2+ microdomain signals as in healthy cells. The origin and function of astrocyte Ca2+ microdomain signals rests enigmatic, and the detailed mechanistic investigation of the damage mechanism is beyond the scope of this work.

Finally, in as much as we conducted all our experiments at 31–34°C bath temperature (a common practice in slice electrophysiology), one might argue that laser-induced temperature gradients actually bring the recording temperature closer to physiological 37°C. Our observation of more frequent microdomain Ca2+ activity and the occurrence of somatic Ca2+ signals could then likely be physiological, and the quiet state is a result of the cell being too cold. Yet, even if this would be the case, because of the flying spot geometry, we are in a nonequilibrium situation, and the local heating will depend, in addition to the average power, on the recording depth and on scan parameters that influence local temperature gradients like the pixel dwell time, the spatial resolution, the use of flyback blanking, and the exact scan trajectory; this thermal-gradient nonequilibrium is not a recording condition in which physiologically meaningful data can be acquired. It will be interesting to investigate how different 2P geometries (single-spot sweeps versus resonant scanning, single-spot versus multispot geometries, raster scan versus random-access scanning, etc.) influence the result. Only the combined monitoring of the local temperature at the recording sites and 2P Ca2+ imaging can clarify this issue. Although future work will address this important question, one important conclusion we can already draw at this stage is that 2P Ca2+ imaging at tens of mW laser powers and with a single-spot geometry alters the tissue state and physiology under study.

Toward even shorter pulses

Our study illustrates the potential benefit of shorter pulses and lowering for 2P excitation of GCaMP-based indicators at 920 nm and in the 100-fs regime. The 90-fs pulses used here were the minimum we could attain with our laser, microscope optics, the 20×/0.95w objective, and the precompensation optics at 920 nm. Even shorter pulses might be beneficial (60,61). This strategy will eventually be bounded at some shortest tolerable pulse length because the resulting higher peak energies will in turn favor nonlinear photobleaching and photodamage pathways having a power exponent m > 2. The demonstration that phase-optimized 28-fs pulses reduced the bleaching rate of EGFP by a factor of four while maintaining the same intensity of the fluorescence signal (62) let us predict that there still might be some room for a further reduction of NIR-induced damage for brain imaging with even shorter pulses.

Conclusions

Overall, we conclude on a perspective similar to Icha et al. (49), who stated that “there are often subtler consequences of illumination that are imperceptible when only the morphology of samples is studied.” Somatic astroglial Ca2+ signals in the absence of neuronal stimulation are a clear warning light for the onset of photodamage, and long before somatic transients are detectable, a heat-induced alteration of microdomain Ca2+ activity in the astrocyte periphery is observable. This transition from physiological to aberrant Ca2+ microdomain signals is more difficult to spot than the somatic hyperactivity, even when using a detailed analysis of several spike parameters. Our finding that pausing acquisitions can reverse the observed photoactivation indicates that reducing the light burden by all means, for example, a combination of shorter pulses, lower pulse rates, sparser “smarter” scan trajectories, and a lower duty cycle illumination alternating burst of imaging with dark episodes should be a promising strategy for maximizing the signal/damage ratio and permitting optical manipulation without compromising the physiology under study.

Author Contributions

E.S. and M.O. designed and performed research. E.S. analyzed the data. M.O. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cendra Agulhon (Paris, France) for breeding the IP3R2-KO mice used in this study and for help with immunofluorescence, Frank Pfrieger (Strasbourg, France) for providing the GLASTcreERT2 mouse line, Marcel van’t Hoff for LABVIEW programming, and Emmanuel Beaurepaire (Palaiseau, France), Erwin Neher (Göttingen, Germany), Stéphane Dieudonné (Paris, France), Manfred Lindau (Göttingen, Germany/Ithaca, NY), and many others for helpful discussions. Patrice Jegouzo, Christophe Tourain (workshop), and the animal house team around Claire Mader provided excellent technical assistance. We thank the late JacSue Kehoe (Paris, France) for carefully reading and commenting on an early version of this manuscript This article is dedicated to the memory of JacSue Kehoe (1935–2019), woman pioneer, colleague, and friend.

We were financed by the European Union (FP6-STRP “AUTO-SCREEN,” FP7 ERA-NET NEURON “NANOSYN,” FP7 JPND “SYNSPREAD,” and H2020 EUROSTARS “OASIS”), the FranceBioImaging large-scale national infrastructure initiative (ANR-10-INSB-04, Investments for the future), and the Region Ile de France (Cancéropôle, “EDISON”). These funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The Oheim lab is a member of the Ecole de Neurosciences de Paris and the C’nano Ile de France excellence clusters for neurobiology and nanobiophotonics, respectively.

Editor: Brian Salzberg.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.10.027.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Denk W., Strickler J.H., Webb W.W. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science. 1990;248:73–76. doi: 10.1126/science.2321027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stosiek C., Garaschuk O., Konnerth A. In vivo two-photon calcium imaging of neuronal networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7319–7324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmchen F., Denk W. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:932–940. doi: 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svoboda K., Yasuda R. Principles of two-photon excitation microscopy and its applications to neuroscience. Neuron. 2006;50:823–839. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao T., O’Connor D.H., Svoboda K. Characterization and subcellular targeting of GCaMP-type genetically-encoded calcium indicators. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Looger L.L., Griesbeck O. Genetically encoded neural activity indicators. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2012;22:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akerboom J., Carreras Calderón N., Looger L.L. Genetically encoded calcium indicators for multi-color neural activity imaging and combination with optogenetics. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2013;6:2. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson G.H., Piston D.W. Photobleaching in two-photon excitation microscopy. Biophys. J. 2000;78:2159–2162. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76762-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koester H.J., Baur D., Hell S.W. Ca2+ fluorescence imaging with pico- and femtosecond two-photon excitation: signal and photodamage. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2226–2236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77063-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopt A., Neher E. Highly nonlinear photodamage in two-photon fluorescence microscopy. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2029–2036. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan Y.P., Llano I., Neher E. Fast scanning and efficient photodetection in a simple two-photon microscope. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1999;92:123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisenburger S., Prevedel R., Vaziri A. Quantitative evaluation of two-photon calcium imaging modalities for high-speed volumetric calcium imaging in scattering brain tissue. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/115659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madisen L., Garner A.R., Zeng H. Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron. 2015;85:942–958. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slezak M., Göritz C., Pfrieger F.W. Transgenic mice for conditional gene manipulation in astroglial cells. Glia. 2007;55:1565–1576. doi: 10.1002/glia.20570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petravicz J., Boyt K.M., McCarthy K.D. Astrocyte IP3R2-dependent Ca(2+) signaling is not a major modulator of neuronal pathways governing behavior. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;8:384. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cesana E., Pietrajtis K., Forti L. Granule cell ascending axon excitatory synapses onto Golgi cells implement a potent feedback circuit in the cerebellar granular layer. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:12430–12446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4897-11.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ducros M., van ’t Hoff M., Oheim M. Efficient large core fiber-based detection for multi-channel two-photon fluorescence microscopy and spectral unmixing. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2011;198:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oheim M., Beaurepaire E., Charpak S. Two-photon microscopy in brain tissue: parameters influencing the imaging depth. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2001;111:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rueden C.T., Schindelin J., Eliceiri K.W. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18:529. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1934-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bethge P., Carta S., Helmchen F. An R-CaMP1.07 reporter mouse for cell-type-specific expression of a sensitive red fluorescent calcium indicator. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohkura M., Sasaki T., Nakai J. Genetically encoded green fluorescent Ca2+ indicators with improved detectability for neuronal Ca2+ signals. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shigetomi E., Kracun S., Khakh B.S. A genetically targeted optical sensor to monitor calcium signals in astrocyte processes. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:759–766. doi: 10.1038/nn.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haustein M.D., Kracun S., Khakh B.S. Conditions and constraints for astrocyte calcium signaling in the hippocampal mossy fiber pathway. Neuron. 2014;82:413–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rungta R.L., Bernier L.P., MacVicar B.A. Ca2+ transients in astrocyte fine processes occur via Ca2+ influx in the adult mouse hippocampus. Glia. 2016;64:2093–2103. doi: 10.1002/glia.23042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bindocci E., Savtchouk I., Volterra A. Three-dimensional Ca 2+ imaging advances understanding of astrocyte biology. Science. 2017;356:eaai8185. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian L., Hires S.A., Looger L.L. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye L., Haroon M.A., Paukert M. Comparison of GCaMP3 and GCaMP6f for studying astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics in the awake mouse brain. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.König K., Becker T.W., Halbhuber K.J. Pulse-length dependence of cellular response to intense near-infrared laser pulses in multiphoton microscopes. Opt. Lett. 1999;24:113–115. doi: 10.1364/ol.24.000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Podgorski K., Ranganathan G. Brain heating induced by near-infrared lasers during multiphoton microscopy. J. Neurophysiol. 2016;116:1012–1023. doi: 10.1152/jn.00275.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Débarre D., Olivier N., Beaurepaire E. Mitigating phototoxicity during multiphoton microscopy of live Drosophila embryos in the 1.0-1.2 μm wavelength range. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schönle A., Hell S.W. Heating by absorption in the focus of an objective lens. Opt. Lett. 1998;23:325–327. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bánsághi S., Golenár T., Hajnóczky G. Isoform- and species-specific control of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors by reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:8170–8181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwal A., Wu P.-H., Bergles D.E. Transient opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore induces microdomain calcium transients in astrocyte processes. Neuron. 2017;93:587–605.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherwood M.W., Arizono M., Mikoshiba K. Astrocytic IP3 Rs: contribution to Ca2+ signalling and hippocampal LTP. Glia. 2017;65:502–513. doi: 10.1002/glia.23107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasan R., Huang B.S., Khakh B.S. Ca(2+) signaling in astrocytes from Ip3r2(-/-) mice in brain slices and during startle responses in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:708–717. doi: 10.1038/nn.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheppard C.J., Kompfner R. Resonant scanning optical microscope. Appl. Opt. 1978;17:2879–2882. doi: 10.1364/AO.17.002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macias-Romero C., Zubkovs V., Roke S. Wide-field medium-repetition-rate multiphoton microscopy reduces photodamage of living cells. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2016;7:1458–1467. doi: 10.1364/BOE.7.001458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y., Sonek G.J., Tromberg B.J. Physiological monitoring of optically trapped cells: assessing the effects of confinement by 1064-nm laser tweezers using microfluorometry. Biophys. J. 1996;71:2158–2167. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79417-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterman E.J., Gittes F., Schmidt C.F. Laser-induced heating in optical traps. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74946-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picot A., Dominguez S., Emiliani V. Temperature rise under two-photon optogenetic brain stimulation. Cell Rep. 2018;24:1243–1253.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun M.-Y., Devaraju P., Fiacco T.A. Astrocyte calcium microdomains are inhibited by bafilomycin A1 and cannot be replicated by low-level Schaffer collateral stimulation in situ. Cell Calcium. 2014;55:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalmbach A.S., Waters J. Brain surface temperature under a craniotomy. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;108:3138–3146. doi: 10.1152/jn.00557.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X., Leischner U., Konnerth A. LOTOS-based two-photon calcium imaging of dendritic spines in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:1818–1829. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iyer V., Hoogland T.M., Saggau P. Fast functional imaging of single neurons using random-access multiphoton (RAMP) microscopy. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;95:535–545. doi: 10.1152/jn.00865.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salomé R., Kremer Y., Bourdieu L. Ultrafast random-access scanning in two-photon microscopy using acousto-optic deflectors. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2006;154:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duemani Reddy G., Kelleher K., Saggau P. Three-dimensional random access multiphoton microscopy for functional imaging of neuronal activity. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:713–720. doi: 10.1038/nn.2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Icha J., Weber M., Norden C. Phototoxicity in live fluorescence microscopy, and how to avoid it. BioEssays. 2017;39 doi: 10.1002/bies.201700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horton N.G., Wang K., Xu C. In vivo three-photon microscopy of subcortical structures within an intact mouse brain. Nat. Photonics. 2013;7:205–209. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2012.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guesmi K., Abdeladim L., Druon F. Dual-color deep-tissue three-photon microscopy with a multiband infrared laser. Light Sci. Appl. 2018;7:12. doi: 10.1038/s41377-018-0012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nett W.J., Oloff S.H., McCarthy K.D. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ exhibit calcium oscillations that occur independent of neuronal activity. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:528–537. doi: 10.1152/jn.00268.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., Lou N., Nedergaard M. Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling evoked by sensory stimulation in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu H., Ramsey I.S., Clapham D.E. TRPV3 is a calcium-permeable temperature-sensitive cation channel. Nature. 2002;418:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature00882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao B., Coste B., Patapoutian A. Temperature-dependent STIM1 activation induces Ca2+ influx and modulates gene expression. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:351–358. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chowdhury S., Jarecki B.W., Chanda B. A molecular framework for temperature-dependent gating of ion channels. Cell. 2014;158:1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]