Abstract

Childlessness is increasing globally. This study aimed to explore the experiences of childless women who had wanted children. An online survey study was promoted through social media to recruit women aged ≥46 years who were childless by circumstance. The survey remained open for 15 days. In total, 303 survey responses were collected, 176 of which were complete surveys. In total, 15.3% (27/176) of women who had wanted children reported that they had not tried to have children, most commonly due to the lack of a partner (40.7%, 11/27). Of the 139 women who had tried to have children, 70.5% (98/139) had used calendar-based menstrual cycle tracking methods to identify their fertile window, and many had undergone fertility checks including hormone tests (75.5%, 105/139) and ultrasound scans (71.2%, 99/139). A significant proportion of women had experienced a miscarriage (40.2%, 56/139). Many women had decided not to have any fertility treatment (43.2%, 60/139). For those who did, the majority had tried in-vitro fertilization (74.6%, 59/79). The most common reason that women gave for stopping fertility treatment was due to emotional reasons (74.7%, 59/79). When asked how women felt now about their childlessness, the most common issues identified were unhappiness (85/158, 54%), acceptance (43/158, 27%) and happiness (30/158, 19%). There should be more support for unsuccessful fertility patients and other childless women, and more emphasis should be placed upon fertility education in order to ensure that women are better informed about fertility issues.

KEYWORDS: childlessness, childless, fertility, infertility, IVF

Introduction

Childlessness is increasing in middle- and high-income countries, particularly those in Europe (Kreyenfeld and Konietzka, 2017). Some predicted that as society developed, women’s lives would revolve less around childbearing, as a result of greater respect for reproductive rights and protection of gender equality, and women’s increasing economic autonomy and educational achievement (Lesthaeghe, 2010, Van de Kaa, 1987). The purpose of this study was to survey childless women who had wanted children in order to understand what factors led to their childlessness, and to find out whether their attitudes towards not having children had changed over time.

Postponing childbearing has become a Europe-wide trend (Koert and Daniluk, 2017, Kreyenfeld and Konietzka, 2017, Sobotka, 2017). Between 1970 and 2008 across Europe, maternal age at first birth increased from 25 years to 29 years (Mills et al., 2011). In England, from 1970 to 2017, the average maternal age at first birth increased from 23.7 to 28.8 years. This was accompanied by a significant increase in the number of women aged >35 years giving birth for the first time, and the lowest fertility rate on record (Office for National Statistics, 2019a, Office for National Statistics, 2019b). As well as women becoming mothers later than ever, a record high of almost one in five women are childless at the end of their childbearing years (Office for National Statistics, 2018).

Research has shown that lack of a suitable partner is a common reason for many to postpone their childbearing, potentially leading to permanent childlessness (Kapitany and Speder, 2012, Mynarska, 2010). However, recent research shows that other variables such as career advancement, labour market conditions and financial stability are increasingly associated with childlessness in many European countries (Greulich, 2018, Koert and Daniluk, 2017, Kreyenfeld and Konietzka, 2017, Preisner et al., 2018).

Women’s employment in the UK has seen an increase from 57% in 1975 to 78% in 2017 (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2018). More women are now employed from their mid 20s to early 30s (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2018). Childless women are more likely to work than those with children (Office for National Statistics, 2013). Some have linked the increasing career investments at this life stage to increased birth postponement (Kreyenfeld and Konietzka, 2017). In the UK, access to education has also improved, with women 36% more likely than men to start degree courses in 2017 (Universities and Colleges Admissions Service, 2017). More time in education has been associated with greater delays in childbearing, thus increasing childlessness (Clarke and Hammarberd, 2005, Kreyenfeld and Konietzka, 2017).

Postponing childbearing may result in difficulties conceiving as a result of age-related fertility decline (Eriksson et al., 2013, MacDougall et al., 2013). Fertility treatment is widely perceived as the solution to infertility, despite the lack of guaranteed success (Greil et al., 2010, Hampton et al., 2012). The media and the fertility industry are responsible for understating the consequences of age-related fertility decline by presenting examples of women who conceived with assisted reproductive technology (ART) at an advanced age (Campbell, 2011, Everywoman, 2013, MacDougall et al., 2013, Mills et al., 2015). Many women wrongly believe that ART will work until menopause (Harper et al., 2017, MacDougall et al., 2013, Maheshwari et al., 2008). In reality, for women aged 43–44 years, the live birth rate for IVF using their own eggs is 3%, compared with 29% for women aged ≤35 years (Human Fertilisation Embryology Authority, 2018). Despite these data, some women perceive ART as a simple cure for infertility and age-related fertility decline (MacDougall et al., 2013, Mills et al., 2015, Vassard et al., 2016).

Trends of birth postponement have been linked to increased rates of unintended permanent childlessness (Koert and Daniluk, 2017, Sobotka, 2017, Wyndham et al., 2012). Older women who may have postponed childbearing are more likely to experience unfortunate outcomes, including stillbirths and aneuploidy-related miscarriage (Kenny et al., 2013, Laopaiboon et al., 2014, O’Brien and Wingfield, 2018, UK Obstetric Surveillance System, 2019). Recently, a study of childless women found that many had been left childless after repeatedly postponing childbearing (Rybinska and Morgan, 2019).

This study used an online survey to explore the experiences of childless women who had wanted children. The aim was to add to our understanding of the experiences of this growing category of women by recording their thoughts about their reproductive experiences, and by asking them how they felt about being childless now.

Materials and methods

This study included women who did and did not try to have children. Men were not included. Participants were required to be aged ≥46 years; this age was chosen because 45 years is classified by the Office for National Statistics as the end of a woman’s childbearing years (Office for National Statistics, 2019c).

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee at University College London (Ref. 9831/002). To develop the survey, the team initially worked to produce a set of questions that addressed the aims of this project. Additionally, four childless women were consulted during development of the questions. To validate the questions, three of the target population were contacted and invited to comment on the survey via a telephone call with the research team, which is a method called ‘talk aloud’ (Fonteyn et al., 1993, Fowler, 2014, Granello and Wheaton, 2004). The online survey was built using Qualtrics software (Provo, UT, USA).

There has been considerable debate over how to refer to women without children (Basten, 2009, Hird and Abshoff, 2000, Letherby, 2002). In this study, we decided to use the term ‘childless by circumstance’. Given that our participants had wanted children at some point, to describe them as ‘child-free’ seemed inappropriate. Much of the literature on ‘childlessness’ distinguishes between involuntary and voluntary childlessness, when the reality may be that women’s attitudes towards being childless shift over time. We settled on ‘childless by circumstance’ in order not to presuppose the reasons for women’s childlessness, or to assume that women’s attitudes towards their childlessness are fixed and immutable.

The survey was published online for 15 days from 2 to 17 July 2019. It was open to women from any country. To recruit participants, a link was distributed by a research team member’s social media accounts, specifically Twitter, Instagram and Linkedin. Twitter has been shown to be a cost-effective, unique-population-engaging, transparent, anonymous and accessible recruitment method (O’Connor et al., 2013). The sample self-selected, using the snowball effect to recruit via Twitter's retweet function (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981, Saines, 2017).

The qualitative data were analysed in an iterative manner, from raw data proceeding to preliminary analysis (Sandelowski, 1995), to produce a set of similarities between participants’ responses. In this vein, a naturalistic descriptive approach was adopted; this means not preselecting or manipulating variables, and avoiding a-priori application of theoretical concepts, as there is no target phenomena (Lincoln and Guba, 1985, Sandelowski, 2000). Descriptive analysis allows this study to ‘stay closer to its data and to the surface of words and events than researchers conducting grounded theory, phenemonologic, ethnographic, or narrative studies. In qualitative descriptive studies, language is a vehicle of communication, not itself an interpretive structure that must be read’ (Sandelowski, 2000: 336). This permits the study to attribute meaning to exactly what the respondents have stated, while still producing meaningful data (Sandelowski, 2000).

Results

In total, 303 responses were recorded. Some of these responses were incomplete, resulting in a total of 176 complete surveys.

Demographics

The most highly represented country of residence was the UK at 67.0% (118/176), followed by the USA (13.6%, 24/176) and Canada (6.0%, 10/176), with a few women from New Zealand, Australia, Ireland, France, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Ethiopia, Israel, Japan, Spain, and Trinidad and Tobago. The age range was from 46 to 62 years, with the average age being 52 years. All 176 participants identified as female, with 90.9% (160/176) of participants identifying as heterosexual, 6.3% (11/176) as bisexual, 1.1% (2/176) as homosexual and 1.1% (2/176) as pansexual. The majority of participants were Christian (37.5%, 66/176), no religion or belief (37.5%, 65/176), or other (11.9%, 21/176). Other religions recorded were Judaism, Buddhism and Sikhism. The majority of participants self-identified as white (89.8%, 158/176), which included white British, white other or white Irish. Three participants were Black/Black British-Caribbean, two were Asian/Asian British-Indian, one was other Black/African/Caribbean, five were mixed, one was other and five preferred not to say. Six (3.4%) participants had only secondary education, 17 (9.7%) had been educated to A-level/college level, 44 (25.0%) had been educated to undergraduate level, and 97 (55.1%) had postgraduate education. Twelve (6.8%) participants did not answer this question. The majority of participants did not have any disability (n = 133), but 20 had a long-term illness, nine were physically or mobility impaired, nine had other disabilities, three had specific learning difficulties or disabilities, two were sensory impaired, one had general learning disabilities and one preferred not to say. One participant recorded two disabilities. The majority of women were married or in a civil partnership (103, 58.5%), 31 (17.6%) were co-habiting, 18 (10.2%) were single (never married), 16 (9.1%) were separated or divorced, seven (4.0%) were in a relationship, and one preferred not to say.

Did not try to have children

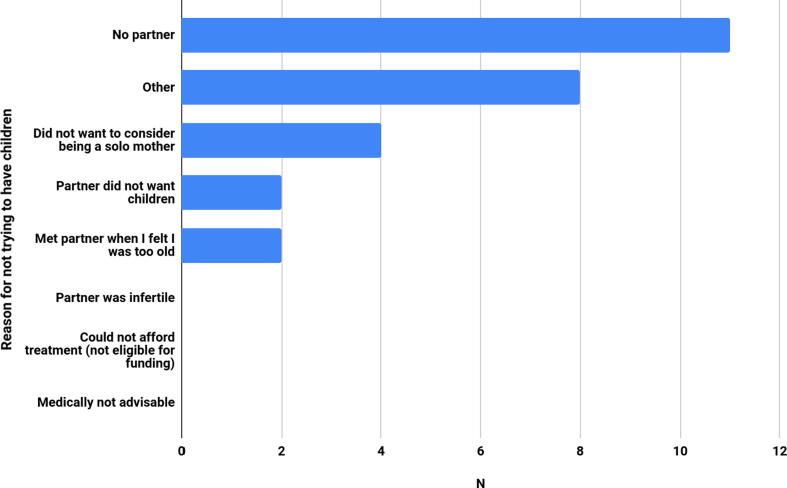

Twenty-seven (15.3%, 27/176) women had not tried to have children. Fig. 1 shows the options the women were given for this question. Eleven (40.7%) of these women had not tried to have children due to the lack of a partner. Eight women selected ‘other’. These women indicated that it was difficult to choose only one of the reasons and reported a combination of options. Two of the participants indicated that they had not prioritized trying to have children highly.

Fig. 1.

Main reason for not trying to have children.

Tried to have children

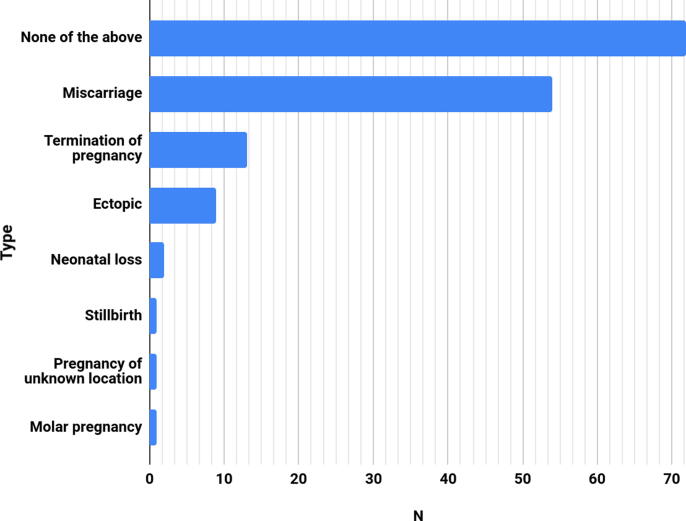

The 139 women who had tried to have children reported their pregnancy-related medical histories (Fig. 2). Participants were able to select multiple answers, as well as enter the number of times they had experienced each of the potential answers. Amongst the 54 participants who had experienced at least one miscarriage (38.8%, 54/139), the average number of miscarriages per participant was 6.3 (standard deviation 2.86, range 1–13). For the 10 participants who had terminated a pregnancy, the average number of abortions per participant was 1.3 (range 1–3). For the nine participants who had experienced an ectopic pregnancy, the average number of ectopic pregnancies was 1.6 (range 1–3).

Fig. 2.

Pregnancy-related history.

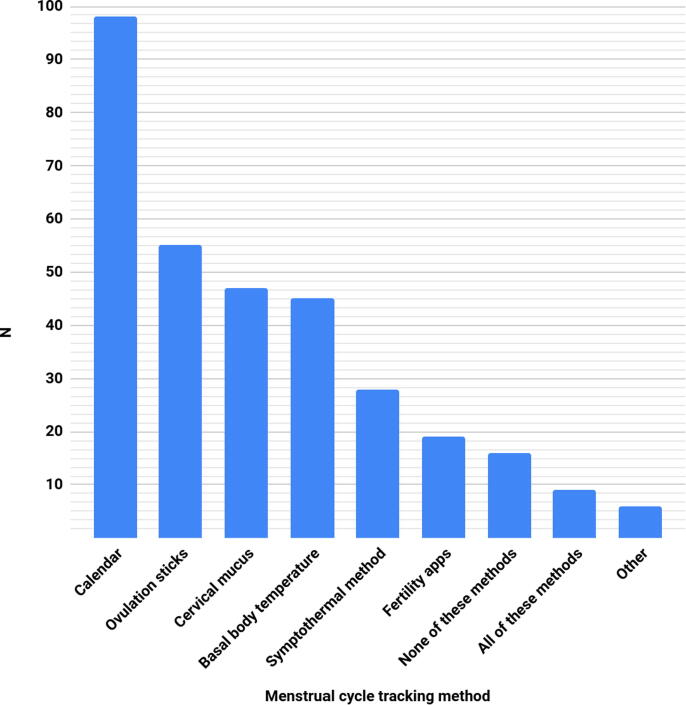

The 139 women who had tried to have children reported their use of menstrual cycle tracking methods to determine their fertile window (Fig. 3). This question had a multiple-choice answer format, so participants may have used and selected more than one method, which is reflected in the data. Ninety-eight (70.5%) women reported using calendar-based menstrual cycle tracking methods, and the second most common method was ovulation sticks (39.6%, 55/139).

Fig. 3.

Menstrual cycle tracking methods used.

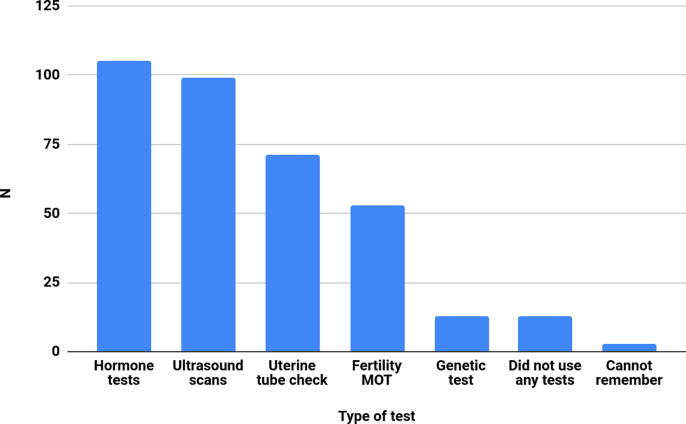

The majority of the 139 women who had tried to have children had undergone hormone tests and ultrasound scans (see Fig. 4). One hundred and five women had undergone hormone tests, 99 women had undergone ultrasound scans, and 71 women had undergone a uterine tube check. This question also had a multiple-choice answer format.

Fig. 4.

Use of fertility tests amongst those who tried to have children.

How women tried to have children

Overall, 15 women (10.8%) had not used their intimate partners’ sperm exclusively. This means that 123 participants (123/139, 88.5%) only used their intimate partners’ sperm when trying to have children.

Of the 15 participants who had not used their intimate partner’s sperm exclusively, they mainly used sperm from a fertility clinic (46.7%, 7/15) or direct from a sperm bank (40.0%, 6/15) (Table 1). One participant selected ‘other’ and specified that they had used sperm from different men with the intention of being a single mother.

Table 1.

Donor sperm source.

| Where did you get the donor sperm from? | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Via a fertility clinic | 7/15 (46.7%) |

| Direct from a sperm bank | 6/15 (40.0%) |

| Friend | 2/15 (13.3%) |

| Online | 0/15 (0.0%) |

| Other | 1/15 (6.6%) |

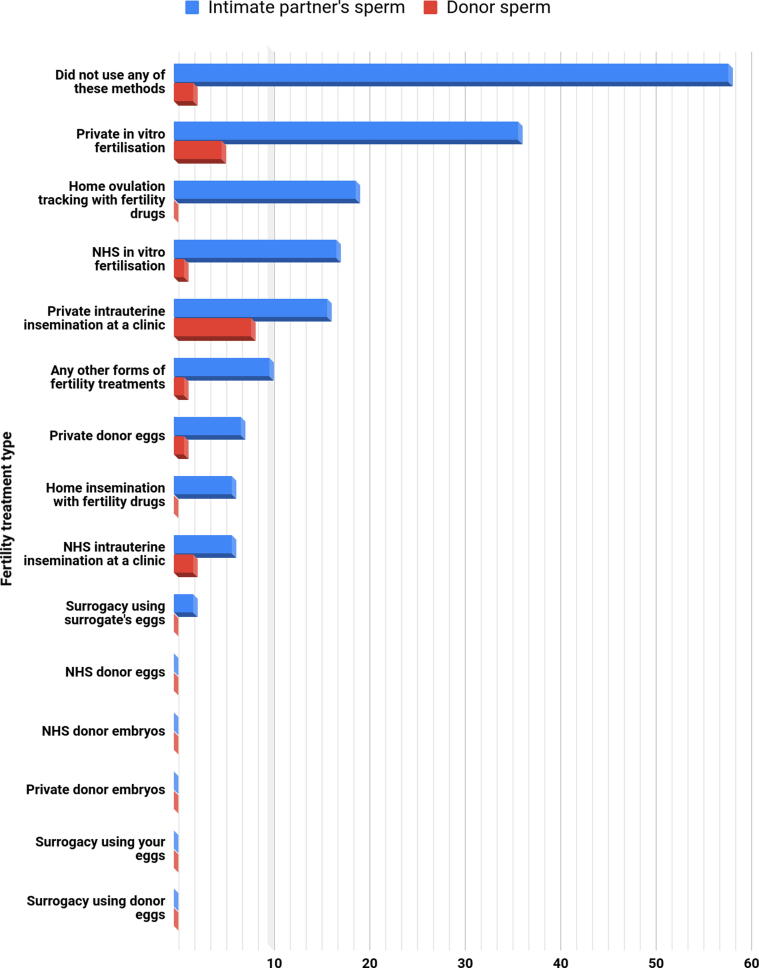

A large proportion of women had decided not to have any fertility treatment (43.2%, 60/139), of which 41.7% (58/139) had tried to conceive with their intimate partner’s sperm and 1.4% (2/139) with donor sperm (but not via a fertility clinic). For the 79 women who had undergone fertility treatment, 81.0% (64/79) had used their intimate partner’s sperm and 19.0% (15/79) had used donor sperm. The majority had tried in-vitro fertilization (IVF) (74.7%, 59/79, mainly privately funded. Of the 59 women who had tried IVF, 89.8% (53/59) had used their intimate partner’s sperm and 10.2% (6/59) had used donor sperm (Fig. 5). However, for those who had used donor sperm, the most popular method was intrauterine insemination (66.6%, 10/15). Only 34.4% (22/64) of women had used their intimate partner’s sperm for intrauterine insemination. Of the 64 women who had used their intimate partner’s sperm, 19 (29.7%) women also used home ovulation tracking and fertility drugs. One of 15 (6.7%) women had used donor sperm and donor eggs, and seven of 64 (10.9%) women had used their intimate partner’s sperm and donor eggs. Two of 64 (3.1%) women had used their intimate partner’s sperm and surrogacy with the surrogate’s eggs.

Fig. 5.

Use of fertility treatment. NHS, National Health Service.

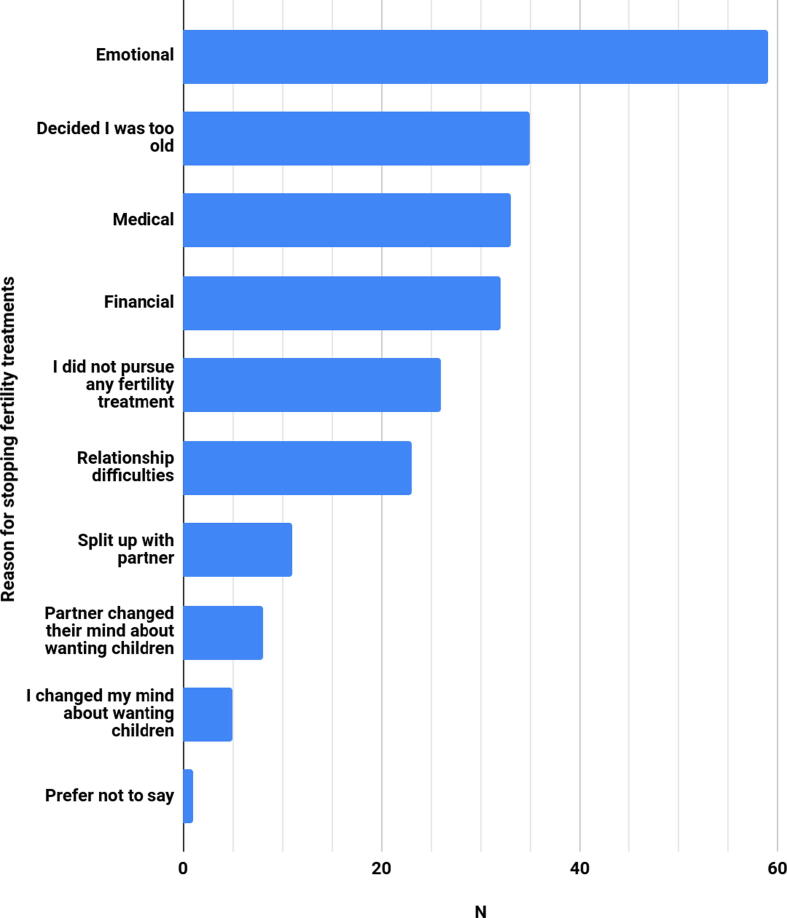

The participants reported why they permanently stopped fertility treatment (Fig. 6). Participants were able to select more than one answer. For the 79 women who had undergone fertility treatment, the majority (74.7%, 59/79) reported having had emotional reasons for stopping. Thirty-five (44.3%) women stopped because they decided they were too old, 41.8% (33/79) reported medical reasons behind stopping, 40.5% (32/79) reported financial reasons for stopping treatment, and 29.1% (23/79) reported stopping due to relationship difficulties.

Fig. 6.

Reasons for permanently stopping fertility treatment.

Adoption

The number of women who had considered adoption but decided not to try was 36.0% (50/139), followed by 31.7% (44/139) who had not tried to adopt and 13.7% (19/139) who had tried to adopt. Twenty-five of 139 women (18.0%) ticked ‘other’, which included eight participants whose partners did not approve of adoption, and four participants who reported being unable to cope with another rejection in the process of trying to have a child.

Still thinking of having children

The 139 participants were asked if they were still considering having children. One hundred and twenty (86.3%) women said no, four (2.9%) said yes, and 15 (10.8%) said they were unsure.

Have feelings about being childless changed since they stopped trying to have children?

As the final part of the survey, all 176 participants were asked if their feelings about being childless have changed since they stopped trying to have children. One hundred and fifty participants chose to answer this question by entering a free-text response. These data were analysed for emergent patterns across responses. Broadly speaking, 88/150 (58.6%) responses demonstrated a sense of unhappiness overall, 37/150 (24.6%) responses referred to a sense of partial acceptance of their circumstances, and 25/150 (16.6%) responses demonstrated a sense of happiness or having embraced their circumstances. A descriptive approach was adopted in analysis, so the most common patterns emerging from the data have been charted in Table 2. Some verbatim excerpts of the data have also been included.

Table 2.

Tone identified from participants’ responses to how their feelings about being childless have changed since they stopped trying to have children.

| Tone identified | n (%) | Example responses from data |

|---|---|---|

| Unhappiness | 88/150 (59%) | Participant A – ‘Childlessness has accompanied a generally challenging relationship story. Therefore, I never was in a relationship which felt settled enough to bring children into. I have become more aware of the grief I carry around not being a mother. The loss has affected me more than any physical need to have children I experienced.’ Participant B – ‘Still devastated and heartbroken. It is a silent grief which I carry with me always. I am living with this and trying to come to terms with it.’ |

| Gradual acceptance | 37/150 (25%) | Participant C – ‘Mostly I’ve accomplished acceptance. But every so often I go back and forth on using donor eggs. It helps that I have many childless friends.’ Participant D – ‘Yes and no. I am still so disappointed and sad that my husband and I never had kids. It will always be a huge loss. But I can’t live forever in grief and I really try to focus on the gifts I have. My husband is an amazing man.’ |

| Embraced their circumstances/ happiness | 25/150 (17%) | Participant E – ‘I’ve come to terms with not having children, it doesn’t hurt as much any more. In fact sometimes I think that maybe it was for the best as my husband and I have a good life. I feel bad for saying this, it’s like saying maybe I never wanted them badly enough…’ Participant F – ‘Yes but it has taken MANY years 5 + since stopping trying to conceive to grieve the loss and finally accept that it wasn’t meant to be, life can go on AND having children is not the only way to find meaning, contribute to society or play an important role in children’s lives.’ |

How do they feel now about being childless?

When asked how they feel about being childless now, 158/176 women chose to answer this question with a free-text response. Overall, 85/158 (53.5%) responses demonstrated unhappiness, 43/158 (27.2%) responses spoke of gradual acceptance, and 30/158 (19.0%) responses demonstrated happiness. Some responses were more difficult to categorize. A similar descriptive approach was adopted in this analysis, with the most common themes tabulated in Table 3, accompanied by verbatim quotes from the data.

Table 3.

Tone identified from participants’ responses to how they feel about being childless now.

| Tone identified | n (%) | Example responses from data |

|---|---|---|

| Unhappiness | 85/158 (54%) | Participant G – ‘Sometimes I wonder how different my life would be. As I watch my friends and family see their children graduate from high school, college, get married, have their own children, I feel a profound emptiness. I will never experience these joys. I feel my advanced years will be lonely having no family of my own. My life has a certain emptiness.’ Participant H – ‘Lost. Hurt. Alone. Excluded. Not fitting in. Condescended to. Disregarded. Thought less of. Ashamed. Embarrassed.’ |

| Acceptance | 43/158 (27%) | Participant I – ‘I am more at peace with it but it is still very painful when I think too much about what we went through. This questionnaire has dragged up some memories and emotions that I have managed to put in a box most of the time. I have learned to enjoy life without children. I realized we had a disposable income which we would never have had if we’d had kids. So retiring at 60 and going on amazing holidays, now I see as benefits of being childless – but it took me too long I think. I see how my husband loves kids and that still breaks my heart. I had a great career which I threw myself into and got a fellowship award for outstanding contribution to my profession which I am very proud of. But I fear for the future, fear being old and with no family to do the things we have done for our parents in their 80s.’ Participant J – ‘I have learned to accept it. However I believe our society falsely believes the most important thing a woman can do is be a mother. I can be all kinds of impactful towards society without ever being a mother.’ |

| Happiness | 30/158 (19%) | Participant K – ‘Yes, now I’m very happy with myself and my life and this is because I’ve taken the initiative myself, worked on my grief and found the appropriate support.’ Participant L – ‘I have accepted it. Life must go on. As we had the treatments, there are no regrets because we did try. My life hasn’t turned out the way I imagined it would do, but I honestly think that it is better in terms of having spare time to do almost anything that I want. I love and appreciate my many friends – some of whom are also childless, but certainly not all of them.’ |

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the fertility journeys of childless women who had wanted children. We aimed to determine what led to women becoming permanently childless, and to explore their thoughts about being childless. Our intention was to avoid presupposing why women were childless, allowing them to present their own perceptions of their childlessness.

Wanted children but did not try

Despite all 176 women wanting children, 16.3% had not tried, mainly due to lack of a partner. Our data are therefore consistent with recent research which has found that the majority of childless women were partnered (Greulich, 2018, Preisner et al., 2018). There is evidence that women are increasingly turning to fertility preservation methods and childbearing postponement due to difficulties in finding a partner with whom to have children (Baldwin et al., 2019, Berrington, 2004, Kapitany and Speder, 2012, Mynarska, 2010). Postponing childbearing is linked to increasing childlessness, so those who did not try to have children in this study may represent a similar group to the non-partnered fertility postponers and preservers found in other research.

Wanted children and tried

We wanted to ask women if and how they tracked their fertile window. A recent study of 612,613 ovulatory cycles from 124,648 women found that calendar-based methods cannot identify the fertile window effectively or reliably (Bull et al., 2019). Due to variations in follicular phase length, ovulation cannot be reliably predicted on day 14 as is commonly thought (Bull et al., 2019, Prior et al., 2015). However, 70.5% of our participants had used calendar-based methods. Fertility education needs to be disseminated effectively in order to improve women’s understanding. Research has shown that when fertility knowledge is poor, unintentional childlessness becomes more likely (Boivin et al., 2018, Garcia et al., 2018). By increasing women’s knowledge around tracking their fertility, unintentional childlessness could be decreased.

A large number of women in this survey had experienced at least one miscarriage (40.2%), which is high compared with the one in four risk in the general population (Warburton and Fraser, 1964). Regan et al. (1989) showed a lower miscarriage rate in parous women (>5%) compared with nulliparous women (24%). However, there are large variations between different populations of women, as a recent study of parous women reported a miscarriage rate of 43% (Cohain et al., 2017). In our study, the average number of miscarriages per participant was 6.3, with one woman experiencing 13 miscarriages. This probably reflects our population of women who had fertility issues.

It is interesting that, in our study, 43.2% of women had not undergone any fertility treatment. This is something that could be explored in future studies to determine why women would not embark on fertility treatment. Reasons may include affordability and psychological consequences (see reasons for stopping IVF below). Of those who had undergone fertility treatment, privately funded IVF was the most common treatment. For those who had used donor sperm, IVF was the second-most common method (25%), with intrauterine insemination the most common (40%). Twelve percent of women had used donor eggs, which is higher than the overall number of 4% reported by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, but should perhaps be expected given the older population in this survey.

Emotional reasons were the most common explanation for stopping fertility treatment (74.7%). This is consistent with the literature on unsuccessful fertility treatment, which has demonstrated that fertility treatment can cause greater stress than infertility itself; and the greater the duration of time spent undergoing fertility treatment, the greater the increase in fertility-related distress (Greil et al., 2011, Martins et al., 2014). Some studies have found that when people undergoing unsuccessful fertility treatment did not receive appropriate psychosocial or emotional support, there were multiple negative impacts on their lives (e.g. splitting from partners; developing depressive disorders; and decreased life, marital and sexual satisfaction) (Daniluk and Tench, 2011, Holley et al., 2015, Martins et al., 2014). Through providing people with emotional support by teaching coping strategies and providing counselling services, the negative impacts of unsuccessful fertility treatment can be alleviated, at least to some extent (Gameiro et al., 2015, Greil et al., 2011, Peterson et al., 2011). Given evidence of the negative impact of unsuccessful fertility treatment, and the benefits of emotional support through this process, more ought to be done by fertility treatment providers in offering support. Overall, 40.5% of women stopped fertility treatment for financial reasons. IVF funding is unequal globally. In some countries, healthcare systems fund the majority of cycles, such as Belgium and Israel, whereas other countries fund a minority of cycles or none, such as the UK and the USA.

How women felt about being childless

Studies have shown that those unable to become parents encounter a sense of failure and deep longing (Eriksson et al., 2013, Kapitany and Speder, 2012, Koert and Daniluk, 2017).

In our study, more women expressed negative feelings about their childlessness than women who were neutral or had positive feelings. The open-text responses convey that many women suffer a sense of sadness and grief as a result of the loss of the opportunity to have a child. Many conveyed feelings of ostracism due to their inability to experience parenthood. These results corroborate much of the literature, whereby loss and grief are experienced amongst other negative feelings (Bell, 2013, Ferland and Caron, 2013, Rich et al., 2011). Alongside our results, much of the research into women’s perceptions of their childlessness demonstrate that many of these women live with fertility-related distress. More importantly, there appears to be inadequate support available to women who are distressed by their childlessness.

Limitations

In addition to the obvious omission of men from this study, this study encountered a few limitations. Only one of the team used social media. From a methodological point of view, 127 participants dropped out during the survey. This may have been prompted by the personal nature of the questions. The attrition left us with 127 sets of incomplete data, which had to be excluded. Additionally, using a social-media-based snowball sampling approach meant that the sample was open to self-selection bias. Although difficult to determine, this could go some way to explaining the sample’s homogeneity, as participants were likely to be from a specific subset of social-media-using childless women who are active on sites relating to childlessness.

The survey was only advertised on social media and was promoted through groups dealing with issues of being childless. This may have biased the results towards women who have not come to terms with being childless.

Conclusion and future research

The key results that have featured in this article demonstrate that there is much work to be done, not only in supporting childless women better, but in developing women’s fertility knowledge. These two aspects can work in tandem. Many women who did try to have children used menstrual cycle tracking methods that are unlikely to indicate their fertile periods reliably. Improved information provision could assist these women in better understanding their fertile window. In the same fashion, improved fertility knowledge may assist women in understanding the realistic sequelae of their age-related fertility decline, and further help them to know how to take action in relation to their childbearing intentions. In addition, more accurate information around the likelihood of successful live births in women of advanced age could aid these women’s preparation for the emotional toll of unsuccessful treatments. Fertility clinics certainly ought to offer more support for those whose treatment does not work. For those women who were unable to even try to have children, more National Health Service funding for fertility treatment and more accessible fertility preservation techniques might have added to their options, but it would certainly not guarantee success.

It should be clear that more work must be done to advance our understanding of the experiences of those living with childlessness, regardless of their reasons for not having children. The male version of this study is underway. Further exploration of the motivations of women who chose to remain childless, and did not ever attempt to conceive, could further develop our understanding of women’s lives today. A more in-depth study could try to evaluate different ways to better support women through their fertility treatment, and particularly through its failure. Finally, research ought to be undertaken on practical means of improving fertility education to enable both women and men to be better informed about fertility, infertility and its treatment.

Declaration

The authors report no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jessica Hepburn, Kelly De Silva and Katy Lindermann for their valuable advice throughout this project.

Biography

Dilan Chauhan is a registered midwife who currently works at University Hospital Lewisham (UK). He has also completed an MSc in Women's Health at University College London. His academic focus has been primarily on areas of women's health, specifically maternity care, women's issues in global contexts, and social aspects of women's issues.

References

- Baldwin K., Culley L., Hudson N., Mitchell H. Running out of time: exploring women’s motivations for social egg freezing. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019;40:166–173. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2018.1460352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basten, S., 2009. Voluntary childlessness and being Childfree. The Future of Human Reproduction: Working Paper #5.

- Bell K. Constructions of “Infertility” and some lived experiences of involuntary childlessness. Affilia. 2013;28:284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Berrington A. Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Popul. Trends. 2004;117:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki P., Waldorf D. Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981;10:141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J., Koert E., Harris T., O’Shea L., Perryman A., Parker K., Harrison C. An experimental evaluation of the benefits and costs of providing fertility information to adolescents and emerging adults. Hum. Reprod. 2018;33:1247–1253. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J.R., Rowland S.P., Scherwitzl E.B., Scherwitzl R., Danielsson K.G., Harper J. Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles. NPJ Digital Med. 2019;2:83. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P. Boundaries and risk: media framing of assisted reproductive technologies and older mothers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;72:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke V.E., Hammarberd K. Reasons for delaying childbearing: a survey of women aged over 35 years seeking assisted reproductive technology. Aust. Fam. Physician. 2005;34:187–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohain J.S., Buxbaum R.E., Mankuta D. Spontaneous first trimester miscarriage rates per woman among parous women with 1 or more pregnancies of 24 weeks or more. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:437. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1620-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniluk J.C., Tench E. Long-term adjustment of infertile couples following unsuccessful medical intervention. J. Counsell. Develop. 2011;85:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson C., Larsson M., Svanberg A.S., Tyden T. Reflections on fertility and postponed parenthood – interviews with highly educated women and men without children in Sweden. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2013;118:122–129. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2012.762074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everywoman J. Cassandra’s prophecy: why we need to tell the women of the future about age-related fertility decline and ‘delayed’ childbearing. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2013;27:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferland P., Caron S.L. Exploring the long-term impact of female infertility: a qualitative analysis of interviews with postmenopausal women who remained childless. Family J. 2013;21:180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fonteyn M.E., Kuipers B., Grobe S.J. A description of think aloud methods and protocol analysis. Qual. Health Res. 1993;3:430–441. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler F.J. fifth ed. Sage Publications; California: 2014. Survey Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Gameiro S., Boivin J., Dancet E., de Klerk C., Emery M., Lewis-Jones C., Thorn P., Van den Broeck U., Venetis C., Verhaak C.M., Wischmann T., Vermeulen N. ESHRE guideline: routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction—a guide for fertility staff. Hum. Reprod. 2015;30:2476–2485. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D., Brazal S., Rodriguez A., Prat A., Vassena R. Knowledge of age-related fertility decline in women: a systematic review. Eur. J. Obstetrics Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018;230:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granello D.H., Wheaton J.E. Online data collection: strategies for research. J. Counsell. Develop. 2004;82:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Greil A.L., McQuillan J., Lowry M., Shreffler K.M. Infertility treatment and fertility-specific distress: a longitudinal analysis of a population-based sample of U.S. women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil A.L., Slauson-Blevins K., McQuillan J. The experience of infertility: a review of recent literature. Sociol. Health Illn. 2010;32:140–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greulich A. Childlessness in Europe: contexts, causes, and consequences. Population. 2018;73:150–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton K.D., Mazza D., Nexton J.M. Fertility-awareness knowledge, attitudes, and practices of women seeking fertility assistance. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012;69:1076–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J.C., Boivin J., O’Neill H.C., Brian K., Dhingra J., Dugdale G., Edwards G., Emmerson L., Grace B., Hadley A., Hamzic L., Heathcote J., Hepburn J., Hoggart L., Kisby F., Mann S., Norcross S., Regan L., Seenan S., Stephenson J., Walker H., Balen A. The need to improve fertility awareness. Reprod. BioMed. Soc. Online. 2017;4:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hird M.J., Abshoff K. Women without children: a contradiction in terms? J. Comp. Family Stud. 2000;31:347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Holley S.R., Pasch L.A., Bleil M.E., Gregorich S., Katz P.K., Adler N.E. Prevalence and predictors of major depressive disorder for fertility treatment patients and their partners. Fertil. Steril. 2015;103:1332–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Fertilisation Embryology Authority, 2018. Fertility treatment 2014-2016: Trends and figures. Retrieved from: https://www.hfea.gov.uk/media/2563/hfea-fertility-trends-and-figures-2017-v2.pdf on 28/1/19.

- Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2018. The rise and rise of women’s employment in the UK. Retrieved from: https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN234.pdf on 26/1/2019.

- Kapitany B., Speder Z. Realization, postponement or abandonment of childbearing intention in four European Countries. Population (Engl. Ed.) 2012;67:599–629. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny L.C., Lavender T., McNamee R., O’Neill S.M., Mills T., Khashan A.S. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: evidence from a large contemporary cohort. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koert E., Daniluk J.C. When time runs out: reconciling permanent childlessness after delayed childbearing. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2017;35:342–352. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2017.1320363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M., Konietzka D., editors. Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences. Springer International Publishing; New York: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Laopaiboon, M., Lumbiganon, P., Intarut, N., Mori, R., Ganchimeg, T., Vogel, J.P., Souza, J.P., Gulmezoglu, A.M., on behalf of the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal Newborn Health Research Network, 2014. Advanced maternal age and pregnancy outcomes: a multicountry assessment. BJOG 121, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lesthaeghe R. The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Popul. Develop. Rev. 2010;36:211–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letherby G. Childless and bereft?: stereotypes and realities in relation to ‘Voluntary’ and ‘Involuntary’ childlessness and womanhood. Sociol. Inquiry. 2002;72:7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. SAGE Publication; California: 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall K., Beyene Y., Nachtigall R.D. Age shock: misperceptions of the impact of age on fertility before and after IVF in women who conceived after age 40. Hum. Reprod. 2013;28:350–356. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari A., Porter M., Shetty A., Bhattacharya S. Women’s awareness and perceptions of delay in childbearing. Fertil. Steril. 2008;90:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M.V., Costa P., Peterson B.D., Costa M.E., Schmidt L. Martial stability and repartnering: infertility-related stress trajectories of unsuccessful fertility treatment. Fertil. Steril. 2014;102:1716–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M., Rindfuss, R.R., McDonald, P., te Velde, E., on behalf of the ESHRE Reproduction and Society task Force, 2011. Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum. Reprod. Update 17(6), 848–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mills T.A., Lavender R., Lavender T. ‘Forty is the new twenty’: an analysis of British media portrayals of older mothers. Sexual Reprod. Healthcare. 2015;6:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynarska M. Deadline for parenthood: fertility postponement and age norms in Poland. Eur. J. Popul. 2010;26:351–373. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien Y., Wingfield M.B. Reproductive ageing - turning back the clock. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2018;2018:e1–e7. doi: 10.1007/s11845-018-1769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A., Jackson L., Goldsmith L., Skirton H. Can I get a retweet please? Health research recruitment and the Twittersphere. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013;70:599–609. doi: 10.1111/jan.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics, 2013. Women in the labour market: 2013. Report retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/womeninthelabourmarket/2013-09-25 on 29/1/19.

- Office for National Statistics, 2018. Childbearing for women born in different years, England and Wales: 2017. Report retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/bulletins/childbearingforwomenbornindifferentyearsenglandandwales/2017 on 21/1/19.

- Office for National Statistics, 2019a. Birth characteristics in England and Wales: 2017. Report retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales/2017 on 9/8/19.

- Office for National Statistics, 2019b. Births in England and Wales: 2018. Report retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthsummarytablesenglandandwales/2018 on 9/8/19.

- Office for National Statistics, 2019c. User guide to birth statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/methodologies/userguidetobirthstatistics on 6/9/19.

- Peterson B.D., Pirritano M., Block J.M., Schmidt L. Marital benefit and coping strategies in men and women undergoing unsuccessful fertility treatments over a 5-year period. Fertil. Steril. 2011;95:1759–1763.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisner K., Neuberger F., Posselt L., Kratz F. Motherhood, employment, and life satisfaction: trends in Germany between 1984 and 2015. J. Marriage Family. 2018;80:1107–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Prior J.C., Naess M., Langhammer A., Forsmo S. Ovulation prevalence in women with spontaneous normal-length menstrual cycles – a population-based cohort from HUNT3, Norway. PLOS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan L., Braude P.R., Trembath P.L. Influence of past reproductive performance on risk of spontaneous abortion. BMJ. 1989;299:541–545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6698.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich S., Taket A., Graham M., Shelley J. ‘Unnatural’, ‘Unwomanly’, ‘Uncreditable’ and ‘Undervalued’: the significance of being a childless woman in Australian Society. Gender Issues. 2011;28:226–247. [Google Scholar]

- Rybinska A., Morgan S.P. Childless expectations and childlessness over the life course. Soc. Forces. 2019;97:1571–1602. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saines, S., 2017. Using Social Media: Recruiting Research Participants via Twitter. Post retrieved from: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/osc/2017/11/03/twitter-recruiting-research-participants/ on 26/8/19.

- Sandelowski M. Focus on qualitative methods – qualitative analysis: what it is and how to begin. Res. Nurs. Health. 1995;18:371–375. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods – whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T. Post-transitional fertility: the role of childbearing postponement in fuelling the shift to low and unstable fertility levels. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2017;49:S20–S45. doi: 10.1017/S0021932017000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Universities and Colleges Admissions Service, 2017. 2017 entry UCAS Undergraduate reports by sex, area background, and ethnic group. Retrieved from: https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/undergraduate-statistics-and-reports/ucas-undergraduate-reports-sex-area-background-and-ethnic-group/2017-entry-ucas-undergraduate-reports-sex-area-background-and-ethnic-group on 27/1/19.

- UK Obstetric Surveillance System, 2019. Pregnancy at Advanced Maternal Age. Report retrieved from: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/ukoss/current-surveillance/ama on 9/8/19.

- Van de Kaa D.J. Europe’s second demographic transition. Popul. Bull. 1987;42:1–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassard D., Lallemant C., Nyboe A.A., Macklon N., Schmidt L. A population-based survey on family intentions and fertility awareness in women and men in the United Kingdom and Denmark. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2016;121:244–251. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2016.1194503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D., Fraser F.C. Spontaneous abortion risk in man: data from reproductive histories collected in a medical genetics unit. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1964;16:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyndham N., Marin Figueira P.G., Patrizio P. A persistent misperception: assisted reproductive technology can reverse the “aged biological clock”. Fertil. Steril. 2012;97:1044–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]