Abstract

This paper extracts, organises and summarises findings on adolescent mental health from a major international population study of young people using a scoping review methodology and applying a bio-ecological framework. Population data has been collected from more than 1.5 million adolescents over 37 years by the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children: WHO Cross-National (HBSC) Study. The paper reviews the contribution that this long standing study has made to our understanding of the individual, developmental, social, economic, cultural determinants of adolescent mental health by organising the findings of 104 empirical papers that met inclusion criteria, into individual, microsystem, mesosystem and macrosystem levels of the framework. Of these selected papers, 68 were based on national data and the other 36 were based on international data, from varying numbers of countries. Each paper was allocated to a system level in the bio-ecological framework according to the level of its primary focus. The majority (51 papers) investigate individual level determinants. A further 28 concentrate primarily on the microsystem level, 6 on the mesosystem level, and 29 on the macrosystem level. The paper identifies where there is evidence on the determinants of mental health, summarises what we have learned, and highlights research gaps. Implications for the future development of this population health study are discussed in terms of how it may continue to illuminate our understanding of adolescent mental health in a changing world and where new directions are required.

Keywords: Adolescent, Population mental health, Social determinants, Determinants of mental health, Cross-national survey, Bio-ecological framework, HBSC

Highlights

-

•

Summary of determinants of adolescent mental health from an international study.

-

•

Application of a novel bio-ecological framework helps to identify gaps in knowledge.

-

•

Accumulated knowledge majors on individual and microsystem level determinants.

-

•

Complexity of determinants requires increased research on meso and macro levels.

Introduction

It is well known that establishing good health for adolescents is essential for their growth and development and doing so can help to secure a range of positive health related outcomes in the future (Sawyer et al., 2012). Mental health is an intrinsic part of health and is fundamental to a good quality of life. Defining it is notoriously complex and varies according to disciplinary perspectives (Dodge et al., 2012). Consequently, it is considered to be multi-dimensional and could include physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and economic aspects (Pollard & Lee, 2003). Many of these aspects have been deemed to have implications for young people's self-esteem, behaviour, attendance at school, educational achievement, social cohesion and future health and life chances (Gómez-López et al., 2019, Mathieson and Koller, 2008, Olweus, 1997). Young people with positive mental health are more likely to possess good problem-solving skills, social competence and a sense of purpose. These are often seen as health assets that can help them rebound from setbacks, thrive in the face of poor circumstances, avoid risk-taking behaviour and generally continue a productive life (Morgan, 2011; Scales, 1999).

In the context of a social determinants approach there is a lot we know about the supportive environments which can help young people to thrive (Viner et al., 2012). As a minimum these would include making improvements to structural factors, as well as optimising access to protective factors over risk factors (Viner et al., 2012). Despite this knowledge, there is still an incomplete understanding of the full range of relevant factors and more importantly how they interact to either impinge or support mental health in the various contexts and environments within which young people live. This lack of a complete picture is illustrated by the fact that there is no simple answer to why some young people thrive under circumstances of considerable adversity while others suffer even though their contexts appear secure and supportive. That said, work stemming from Antonovosky's (1987) theory of salutogenesis has supported insights and further pursuance of this question (Länsimies, Pietilä, Hietasola-Husu, & Kangasniemi, 2017).

One longstanding, large scale, cross-national study, Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children, hereon referred to as HBSC (www.hbsc.org), has, over the past 37 years, been researching the determinants of adolescent mental health, albeit expressed in a range of different ways. It has produced a wealth of knowledge that contributes to our ability to improve the lives of young people. However, the collective understanding arising from it has not been methodically assessed, nor has its contribution to our comprehension of adolescent mental health been determined. The aim of this paper is to organise and summarise the body of work produced by HBSC in journal articles on the determinants of adolescent mental health by applying a bio-ecological conceptual framework as a tool to evaluate its contribution. We use a scoping review methodology to map and synthesise peer reviewed empirical papers arising from the atudy to determine what we have learned about adolescent mental health and its social determinants, since the study began in 1983.

Specific research questions we pose include: How has HBSC conceptualised mental health in adolescents across time and across countries? What are the developmental, social, economic, cultural and temporal determinants of adolescent mental health according to HBSC? How can a bio-ecological systems’ approach help to organise the evidence accumulated so far and to highlight gaps?

The HBSC study

History aim and links with WHO

HBSC is a unique cross-national research study of the health behaviours and health of adolescents in Europe and North America. HBSC was initiated in 1982, by researchers from three countries - Finland, Norway and England and shortly after, the project was adopted by the WHO-Euro region office as a WHO collaborative study. The first HBSC Survey was conducted in 1983/4 in 5 countries (the original three plus Austria and Denmark) using a common research protocol and survey instrument (Aaro et al., 1986). Since 1985/6, HBSC surveys have been conducted every four years in an increasing number of member countries, with the latest survey (2017/2018) carried out in 50 countries in the European Region, and Canada (www.hbsc.org). The HBSC Protocol includes a survey instrument comprising three types of question: mandatory HBSC items - that all countries must include, optional HBSC items - which are available for all countries to include if they choose, and national - which are not part of the HBSC protocol and are selected for inclusion by the national team.

The main aim of HBSC has been to study adolescent health and health behaviours in their social context and understand the various determinants that may influence how these are patterned and change over this developmental stage of the life course. Its approach has been to develop a broad understanding of how young people live; recognising that both the wider society and the social domains that adolescents inhabit are important influences. Health has been conceptualised by HBSC not so much as absence of illness or disease, but rather as both psychological and physical well-being. Further information on the history and development of the HBSC study are presented in Currie et al. (2009a).

HBSC concepts and measures

The conceptual framework adopted by the HBSC founders was an ecological one, similar to Bronfenbrenner's (1992) systems' theory, in which adolescent health and health related behaviours are considered as embedded within the context of the social micro-systems of family, peers, and school (Aaro et al., 1986), which are themselves embedded in meso- and macro-systems. There was an implicit interest in understanding how behaviour related to health. Health related behaviours and psychosocial aspects of health were considered to be key criterion (outcome) variables, with personal and environmental factors in lifestyle as predictors. The importance of demographics and the macrosocial context as influences were also explicitly acknowledged. The conceptual approach is discussed in more detail in Currie et al. (2009a).

The term mental health was not initially used in HBSC but the study's conceptual approach included subjective aspects of health which we now understand to be a component of mental health (Aaro et al., 1986; Antaramian et al., 2010). These were measured with a checklist of subjective health complaints or symptoms. The checklist scores comprise a single scale or two separate factors/sub-scales representing somatic and psychological aspects of subjective health (Haugland et al., 2001; Haugland & Wold, 2001; Hetland et al., 2002). Gariepy et al. (2016a) have evaluated the validity and reliability of the checklist as a measure of mental health which they also term psychological health.

A measure of life satisfaction, the ‘Cantril Ladder’, was included for the first time in the 2005/6 survey instrument and included in all surveys thereafter as mandatory. Respondents are asked to rate their life on the rungs (0-10) of a diagrammatic ladder (Levin & Currie, 2014). Other measures of mental health have been added over time as optional packages of questions. These extend core topics as packages of items that countries can choose to include in their surveys and expand the range of questions that can be asked of the data. Individual countries have also used their own choice of mental health measures at national level.

The determinants of mental health we examine are presented in the Results section, 1.3.

Methods

Scoping review approach

The principles of scoping review methodology were used to guide the process of this study (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Specifically, their 5 step approach was used to identify, select, map and synthesise the data included in the HBSC database of publications. Scoping reviews are used to provide an overview of research carried out in complex areas. This study was interested in the mental health of adolescents and specifically its determinants, both complex areas in their own right. This study also aligns with several of the purposes of scoping reviews put forward by Munn et al. (2018), namely clarifying key concepts and definitions, identifying key characteristics and highlighting knowledge gaps.

The research questions described in section 1. Introduction, represent the first step in the process. The identification of relevant studies is an important step (step 2) and normally involves a broad search of electronic databases, reference lists and grey literature. However, given the purpose of this study was to explore what has been learned from HBSC, the sole database of relevance was the HBSC database of national and international journal articles arising from the survey since it began in 1983 (http://www.hbsc.org/publications/journal/). These papers are generated from nine cross-national HBSC surveys conducted since the first in 1985/86 with the most recent survey in 2017/2018. They are the source of data for consideration in step 3.

International reports are published following each survey cycle and present descriptive findings on the prevalence of health, social and behavioural measures by age, gender and family affluence in each country (King et al., 1996; Currie et al., 2000, 2004, 2008a, 2012a; Inchley et al., 2016, 2020). They are not included in the scoping review conducted for the purposes of this paper.

As with all reviews following a systematic process, step 3 involves selecting studies most relevant for answering the research questions of interest. This was done by making explicit a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Straightforwardly, the inclusion criteria were: peer reviewed empirical papers; published between 1986 (when the first papers were published from HBSC) and August 2020 (when the review was completed) and in English; topic area of focus was mental health.

All terms that have been used by the HBSC Study to measure mental health were used as inclusion criteria. The terms were gathered from HBSC Research Protocols (accessible via www.hbsc.org) and from papers on mental health. They include: mental health, mental well-being/wellbeing, perceived well-being, emotional well-being, spiritual well-being, social well-being, subjective well-being, subjective health, subjective health complaints, psychological complaints, psychological symptoms, psychosomatic complaints, psychosomatic symptoms, life satisfaction, anxiety, depression.

Exclusion criteria were: published reports, peer reviewed papers with a conceptual or methodological focus; peer reviewed HBSC empirical papers published in languages other than English. We also excluded papers which focussed on externalising aspects of mental health such as conduct disorders and self-harm. Our focus in this review was on internalising aspects of mental health. We do however consider papers which consider risk behaviours, such as smoking and alcohol use, as determinants of mental health.

Using the HBSC publications database of journal articles, titles were used to identify papers by searching on the mental health terms listed above. Abstracts were reviewed for key findings on associations between determinants and mental health outcomes and also to identify the levels of the bio-ecological framework which were referenced (see below for details). If insufficient detail was found in the abstract, then the paper itself was retrieved and reviewed. Charting and organising the data in this way comprised step 4.

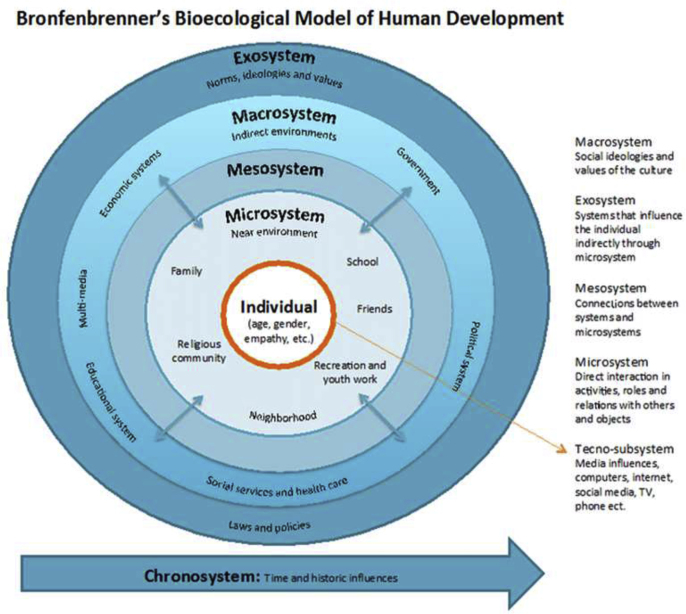

In adopting a bio-ecological framework, the mental health of the individual, developing adolescent is contextualised within different system levels – individual, microsystem, mesosystem and macrosystem. Taking into account the different levels of analysis from individual/developmental up to societal, and across countries and over time, Bronfenbrenner's’ adapted ecological model is used as a framework for organising the information on determinants of adolescent mental health (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). The adapted model includes the maturational stage of the individual which acknowledges the importance of puberty to the health of adolescence. This recognised determinant in adolescent mental health has recently been discussed in an editorial by Currie (2019). The adapted model that Bronfenbrenner developed is known as the ‘process person context time’ model (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). Critically it acknowledges the relevance of biological and genetic aspects of the person and the personal characteristics that individuals bring with them into any social situation. It is presented in Fig. 1. The framework is used to collate, summarise, and report the themes arising from the included studies (step 5).

Fig. 1.

Bronfenbrenner's bio-ecological model of human development.

Results

Once hundred and four papers out of a total of 1047 papers in the HBSC database were found to meet the inclusion criteria for this study, that is they had a primary focus on the determinants of adolescent mental health. Table 1 provides a summary of these papers by geographical context, bio-ecological level and year of publication. The majority of these papers were published from 2010 onwards (88%); 65% of total papers were national; and in general all regions represented within HBSC saw a growth of papers over time. The predominant bio-ecological level was the individual level (49%) followed by the micro level (27%) but macro level publications have grown over time.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected papers.

| YEAR OF PUBLICATION |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–09 | 2010–15 | 2016–2000 | ||

| NO OF PAPERS | 104 | |||

| National | 68 | 8 | 18 | 42 |

| International | 36 | 4 | 15 | 17 |

| National by Region | 68 | 8 | 18 | 42 |

| Western Europe | 21 | 3 | 8 | 10 |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Northern Europe | 13 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Southern Europe | 15 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| North America | 12 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| International Papers by No of Included Countries | 36 | 3 | 16 | 17 |

| >10 | 11 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| 11-19 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| 20-29 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 30-39 | 13 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| 40+ | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| By Bio-Ecological Level | 104 | 11 | 34 | 59 |

| Individual National | 39 | 3 | 9 | 27 |

| International | 12 | 1 | 6 | 5 |

| Micro N | 19 | 3 | 9 | 7 |

| I | 9 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Meso N | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| I | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Macro N | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| I | 14 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| TRENDS (classified within macro level) | 13 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| National | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| International | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

Table 2 (web supplement) provides details of all 104 papers included in the scoping review providing the following information: Level in Bio-ecological model; 1st Author; Year; National (country)/International paper (N of countries); Title; Aim; Mental health measures included; Determinants included. It lists the papers according to the primary level in the bio-ecological that applies: individual, microsystem, mesosystem and macrosystem.

Table 2.

Publication details of selected papers.

| Level in Bio-ecological model | 1st Author | Year | National (country)/International paper (N of countries) | Title | Aim | Mental health measures included | Determinants included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | /////////// | /////// | ///////////////// | //////////////// | //////////////////////////////// | ////////////////// | ////////////////// |

| Individual | Levin | 2009 | National (Scotland) | Mental well-being and subjective health of 11–15 year old boys and girls in Scotland, 1994–2006 | To examine trends and inequalities in mental health | Confidence, happiness, helplessness and feeling left out, multiple health complaints (MHC) | Age, sex/gender, socioeconomic status |

| Individual | Savoye | 2015 | National (Belgium) | Well-being, gender, and psychological health in school-aged children | To test factors related to well-being as explanatory factors of gender differences in psychological complaints | Psychological complaints, life satisfaction, self-confidence, helplessness, and body image | Sex/gender |

| Individual | Walsh | 2010 | National (Israel) | Parents, teachers and peer relations as predictors of risk behaviors and mental well-being among immigrant and Israeli born adolescents. | To examine roles of parents, teachers and peers in predicting risk behaviors and mental well-being among Israeli-born and immigrant adolescents | Multiple health complaints | Migrant status |

| Individual | Walsh | 2018 | National (Israel) | The role of identity and psychosomatic symptoms as mediating the relationship between discrimination and risk behaviors among first and second generation immigrant adolescents | To examines psychosomatic symptoms, and host and heritage identities | Multiple health complaints | Migrant status |

| Individual | Molcho | 2010 | International (12 countries) | Health and well-being among child immigrants in Europe | To examine health, well being and involvement in risk behaviours of immigrant children across twelve European countries | Life satisfaction, subjective health complaints | Migrant status |

| Individual | Carlerby | 2011 | National (Sweden) | Subjective health complaints among boys and girls in the Swedish HBSC study: Focussing on parental foreign background | To explore the associations between foreign extraction and subjective health complaints (SHC) among school-aged children in Sweden | Subjective health complaints | Migrant status |

| Individual | Borraccino | 2018 | National (Italy) | Perceived well-being in adolescent immigrants: it matters where they come from. | To explore whether adolescent immigrants have worse or better perceived well-being | Life satisfaction | Migrant status |

| Individual | Runarsdottir | 2015 | National (Iceland) | Ethnic differences in youth well-being: The role of sociodemographic background and social support. | To explore the psychological well-being of Polish and Asian immigrant youth in Iceland in comparison with their native peers | Life satisfaction, distress | Migrant status |

| Individual | Kuyper | 2016 | National (Netherlands) | Growing Up With the Right to Marry: Sexual Attraction, Substance Use, and Well-Being of Dutch Adolescents | To assess the well-being and substance use of sexual minority adolescents | Psychosomatic complaints and emotional problems | Sexual orientation |

| Individual | Thorsteinsson | 2017 | National (Iceland) | Sexual orientation among Icelandic year 10 adolescents: Changes in health and life satisfaction from 2006 to 2014. | To investigate sexual orientation in relation to mental health and wellbeing | Life satisfaction | Sexual orientation |

| Individual | Paniagua | 2020 | National (Spain) | Under the Same Label: Adopted Adolescents' Heterogeneity in Well-Being and Perception of Social Contexts. | To compare wellbeing of non-adopted and adopted adolescents | Life satisfaction | Adoption status |

| Individual | Pickett | 2020 | National (Canada) | A Contemporary Profile of the Mental Health of Girls from Farm and Non-Farm Environments | To develop a contemporary profile of the mental health of Canadian adolescent girls from farms and determine whether they differed from girls with non-farm backgrounds | Life satisfaction, psychological problems | Farm-living v non-farm living |

| Individual | Whitehead | 2017 | International (33 countries) | Trends in Adolescent Overweight Perception and its Association with Psychosomatic Health 2002–2014: Evidence From 33 Countries. | To examine trends (2002–2014) in the prevalence of adolescent overweight perceptions and their association with psychosomatic complaints. | Psychosomatic health complaints | Overweight |

| Individual | Baile | 2020 | National (Spain) | The Relationship between Weight Status, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Life Satisfaction in a Sample of Spanish Adolescents. | To analyse the relationship between weight status, which is evaluated by means of the body mass index (BMI), and the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and life satisfaction (LS) variables in Spanish adolescents |

Life satisfaction and KIDSCREEN Health related quality of life | Weight status (Body mass index) |

| Individual | Gobina | 2011 | International (19 countries) | The medicine use and corresponding subjective health complaints among adolescents, a cross-national survey | To investigate adolescents' medicine use and association with corresponding health complaints in Europe and USA. | Multiple health complaints | Medicine use |

| Individual | Canha | 2016 | National (Portugal) | Well-being and health in adolescents with disabilities | To investigated similarities and differences between students with and without disabilities regarding their self-ratings of life satisfaction, and psychological and physical symptoms | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic symptoms | Disabilities |

| Individual | Santos | 2015 | National (Portugal) | Psychological well-being and chronic condition in Portuguese adolescents. | To examine the differences in the psychological well-being of Portuguese adolescents living with and without a chronic condition | Psychological symptoms | Chronic condition |

| Individual | Sentenac | 2011 | International (11 countries) | Peer victimization and subjective health among students reporting disability or chronic illness in 11 Western countries. | To compare the strength of the association between peer victimization at school and subjective health according to the disability or chronic illness | Life satisfaction, Multiple Health Complaints | Disability/chronic condition |

| Individual | Lyyra | 2018 | National (Finland) | Loneliness and subjective health complaints among school-aged children. | To examine the association between loneliness and subjective health complaints | Subjective health complaints | Loneliness |

| Individual | Evans | 2019 | National (Ireland) | Comparison of the health and wellbeing of smoking and non-smoking school-aged children in Ireland | To determine the association between smoking and health and well-being indicators among Irish school-aged children. | Life satisfaction, multiple health complaints | Smoking |

| Individual | Braverman | 2016 | National (Norway) | Daily Smoking and Subjective Health Complaints in Adolescence | To examine associations between daily smoking, gender, and self-reported health complaints in five cohorts of adolescents over a 16-year period. | Multiple health complaints | Smoking |

| Individual | Kuntsche | 2004 | National (Switzerland) | Emotional well-being and violence among social and solitary risky single occasion drinkers in adolescence | To test whether risky drinker groups differ in terms of emotional well-being and violence-related variables. | Life satisfaction, depressive mood | Alcohol use |

| Individual | Monshouwer | 2006 | National (Netherlands) | Cannabis use and mental health in secondary school children: Findings from a Dutch survey. | To examine the association between cannabis use and mental health | Somatic health complaints, depression | Cannabis use |

| Individual | Madkour | 2010 | International (5 countries) | Early adolescent sexual initiation and physical/psychological symptoms: a comparative analysis of five nations. | To examine psychosocial correlates of early sexual initiation | Psychological symptoms | Sexual initiation |

| Individual | Arnasson | 2020 | International (6 countries) | Cyberbullying and traditional bullying among Nordic adolescents and their impact on life satisfaction | To examine potential associations between life satisfaction, on the one hand, and traditional bullying and cyberbullying on the other. | Life satisfaction | Bullying |

| Individual | Wang | 2011 | National (US) | Cyber bullying and traditional bullying: Differential association with anxiety. | To compare levels of depression among bullies, victims, and bully-victims of traditional and cyber bullying | Depression | Bullying |

| Individual | Garcia-Moya | 2014 | National (Spain) | Bullying victimization prevalence and its effects on psychosomatic complaints: can sense of coherence make a difference? Trends in bullying victimization in Scottish adolescents 1994–2014: changing associations with mental well-being |

To examine the prevalence of bullying victimization and its impact on physical and psychological complaints | Psychological complaints | Bullying |

| Individual | Cosma | 2017 | National (Scotland) | Trends in bullying victimization in Scottish adolescents 1994–2014: changing associations with mental well-being. | To analyse the changing associations over two decades between bullying victimization and mental well-being in a representative Scottish schoolchildren sample. | Confidence, happiness, psychological health complaints | Bullying |

| Individual | Hong | 2020 | National (US) | Exploring whether talking with parents, siblings, and friends moderates the association between peer victimization and adverse psychosocial outcomes | To explore whether talking with parents, siblings, and friends will moderate the association between peer victimization and internalising problems |

Feel low, feel nervous (2 items from psychosomatic symptoms scale) | Bullying |

| Individual | Carvalho | 2018 | National (Portugal) | Emotional Symptoms and Risk Behaviors in Adolescents: Relationships With Cyberbullying and Implications on Well-Being. | To analyse the relationships between emotional symptoms and cyberbullying | Emotional symptoms | Cyberbullying |

| Individual | Vieno | 2015 | National (Italy) | Cybervictimization and somatic and psychological symptoms among Italian middle school students. | To verify the association between cybervictimization and both psychological and somatic symptoms on a representative sample of Italian early adolescents | Psychological and somatic symptoms | Cyberbulling |

| Individual | Dutkova | 2017 | National (Slovakia) | Is spiritual well-being among adolescents associated with a lower level of bullying behaviour? The mediating effect of perceived bullying behaviour of peers. | To explore the association between spiritual well-being and bullying among Slovak adolescents | Spiritual well-being | Bullying |

| Individual | Gobina | 2008 | International (2 countries) | Bullying and subjective health among adolescents at schools in Latvia and Lithuania. | To investigate the prevalence of bullying among adolescents in Latvia and Lithuania and to study its association with self-rated health, health complaints, and life satisfaction. | Life satisfaction, health complaints | Bullying |

| Individual | Du | 2018 | National (US) | Peer Support as a Mediator between Bullying Victimization and Depression. | To assess the relationship of victimization with depression symptoms was assessed, | Depressive symptoms | Bullying |

| Individual | Walsh | 2020 | International (37 countries) | Clusters of Contemporary Risk and Their Relationship to Mental Well-Being Among 15-Year-Old Adolescents Across 37 Countries | To examine examined the association of clusters of risk behaviours with adolescent mental well-being | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic complaints | Clusters of risk behaviours |

| Individual | Kleszczewska | 2018 | National (Poland) | The Association Between Physical Activity and General Life Satisfaction in Lower Secondary School Students: The Role of Individual and Family Factors. | To investigate the association between physical activity and general life satisfaction in adolescents. | Life satisfaction | Physical activity |

| Individual | Mazur | 2016 | National (Poland) | Behavioural factors enhancing mental health-preliminary results of the study on its association with physical activity in 15–16 year olds | The objective of the study was to determine whether physical activity influences the variability of selected indices of mental health | Social dysfunction (GHQ), anxiety and depression | Physical activity |

| Individual | Brooks | 2014 | National (England) | Associations between physical activity in adolescence and health behaviours, well-being, family and social relations | To examine the association between physical activity and wellbeing | Life satisfaction | Physical activity |

| Individual | Meyer | 2020 | International (44 countries) | The mirror's curse: Weight perceptions mediate the link between physical activity and life satisfaction among 727,865 teens in 44 countries. | To examine the link between physical activity (PA) and life satisfaction in a large international study of adolescents. | Life satisfaction | Physical activity |

| Individual | Piccininni | 2018 | National (Canada) | Outdoor play and nature connectedness as potential correlates of internalized mental health symptoms among Canadian adolescents. | To explore how exposure to nature/outdoors is associated with the prevalence of recurrent psychosomatic symptoms. | Psychosomatic symptoms | Being in nature/the outdoors |

| Individual | Huynh | 2013 | National (Canada) | Exposure to public natural space as a protective factor for emotional well-being among young people in Canada | To examine the relationship between exposure to public natural space and positive emotional well-being among young adolescent Canadians | Emotional well-being (life satisfaction) | Being in nature |

| Individual | Dankulincova Veselska | 2018 | National (Slovakia) | Spirituality but not Religiosity Is Associated with Better Health and Higher Life Satisfaction among Adolescents | To explore the associations of spirituality with self-rated health, health complaints, and life satisfaction of adolescents with the moderating role of religiosity. | Life satisfaction | Spirituality |

| Individual | Gariépy | 2019 | National (Canada) | Teenage night owls or early birds? Chronotype and the mental health of adolescents | To investigate the association between chronotype and mental health | Emotional problems and emotional well-being | Sleep chronotype |

| Individual | Norell-Clarke | 2018 | National (Sweden) | Child and adolescent sleep duration recommendations in relation to psychological and somatic complaints based on data between 1985 and 2013 from 11 to 15 year-olds. | To investigate the association between sleep duration, sleep initiation difficulties and psychological and somatic complaints. | Psychosomatic health complaints | Sleep |

| Individual | Kosticova | 2020 | National (Slovakia) | Difficulties in getting to sleep and their association with emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents: does the sleeping duration influence this association? | To investigate the association between difficulties in getting to sleep/sleep duration and emotional problems | Psychosomatic symptoms | Sleep |

| Individual | Marino | 2016 | National (Italy) | Computer Use, Sleep Difficulties, and Psychological Symptoms Among School-Aged Children: The Mediating Role of Sleep Difficulties | To examine the association between computer use and psychological symptoms among Italian adolescents, taking into account the mediating role of difficulty in getting to sleep. | Psychological symptoms | Computer use and sleep |

| Individual | Vandendriessche | 2019 | International (12 countries) | Does Sleep Mediate the Association between School Pressure, Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Psychological Symptoms in Early Adolescents? A 12-Country Study. | To examine the mediating role of sleep duration and sleep onset difficulties in the association of school pressure, physical activity, and screen time with psychological symptoms in early adolescents. | Psychological symptoms | Sleep, school pressure, physical activity, screen time |

| Individual | Bonniel-Nissim | 2015 | International (9 countries) | Supportive communication with parents moderates the negative effects of electronic media use on life satisfaction during adolescence | To examine the impact of electronic media (EM) use on teenagers' life satisfaction (LS) and to assess the potential moderating effect of supportive communication with parents | Life satisfaction | Electronic media use |

| Individual | Keane | 2017 | National (Ireland) | Physical activity, screen time and the risk of subjective health complaints in school-aged children. | To explore if meeting physical activity and total screen time (TST) recommendations are associated with the risk of reporting health complaints weekly or more |

Psychosomatic health complaints | Computer use and physical activity |

| Individual | Lew | 2019 | National (USA) | Examining the relationships between life satisfaction and alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use among school-aged children | To examine association between life satisfaction and substance use | Life satisfaction | Tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use |

| Individual | Boniel-Nissim | 2015 | International (9 countries) | Supportive communication with parents moderates the negative effects of electronic media use on life satisfaction during adolescence | To examine the impact of electronic media use on teenagers' life satisfaction and to assess the potential moderating effect of supportive communication with parents | Life satisfaction | Electronic media use |

| Microsystem | /////////// | //////// | ///////////////// | /////////////// | ///////////////////////////////// | /////////////////// | ////////////////// |

| Microsystem (Family) | MacIntyre | 2016 | National (Denmark) | High and low levels of positive mental health: are there socioeconomic differences among adolescents? | To examine the socioeconomic patterning of aspects of low and high positive mental health among adolescents | Self-esteem, social competence and self-efficacy | Parents' occupational status |

| Microsystem (family) | Moreno-Maldonado | 2020 | International (2 countries) | Factors associated with life satisfaction of adolescents living with employed and unemployed parents in Spain and Portugal: A person focused approach. | To analyse the association of life satisfaction according to their parents' employment status | Life satisfaction | Parental employment status |

| Microsystem (Family) | Frasquilho | 2016 | National (Portugal) | Parental Unemployment and Youth Life Satisfaction: The Moderating Roles of Satisfaction with Family Life. | To explore the links between parental unemployment and youth life satisfaction by considering the potential moderating roles played by satisfaction with family life and perceived family wealth. | Life satisfaction | Parental employment status |

| Microsystem (Family) | Elgar | 2013 | International (8 countries) | Absolute and relative family affluence and psychosomatic symptoms in adolescents | To explore whether self-reported psychosomatic symptoms in adolescents relate more closely to relative affluence (i.e., relative deprivation or rank affluence within regions or schools) than to absolute affluence. | Psychosomatic symptoms | Family affluence (FAS) |

| Microsystem (Family) | Duinhof | 2020 | National (Netherlands) | Immigration background and adolescent mental health problems: the role of family affluence, adolescent educational level and gender. | To examine to what extent differences in the mental health problems of non-western immigrant and native Dutch adolescents were explained by adolescents' family affluence and educational level and differed with the adolescents' family affluence, educational level, and gender |

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | Family affluence |

| Microsystem (Family) | Morgan | 2019 | National (Wales) | Socio-Economic Inequalities in Adolescent Summer Holiday Experiences, and Mental Wellbeing on Return to School: Analysis of the School Health Research Network/Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Survey in Wales | To examine the role of summer holiday experiences in explaining socioeconomic inequalities in wellbeing | Psychological symptoms | Family affluence (FAS); summer holiday time spent |

| Microsystem (Family) | Elgar | 2017 | International (40 countries) | Early-life income inequality and adolescent health and well-being. | To examine lagged, cumulative, and trajectory associations between early-life income inequality and adolescent health and well-being. | Psychosomatic symptoms and life satisfaction | Family affluence |

| Microsystem (Family) | Buijs | 2016 | National (Czech Republic) | The role of community social capital in the relationship between socioeconomic status and adolescent life satisfaction: mediating or moderating? Evidence from Czech data. | To explain the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and adolescent health and well-being | Life satisfaction | Family affluence and perceived family wealth |

| Microsystem (Family) | Levin | 2010 | National (Scotland) | Family structure, mother-child communication, father-child communication, and adolescent life satisfaction: A cross-sectional multilevel analysis | To investigate the association between mother-child and father-child communication and children's life satisfaction, | Life satisfaction | Family structure, parental communication |

| Microsystem (Family) | Elgar | 2013 | National (Canada) | Family dinners, communication, and mental health in Canadian adolescents | To examine the association between frequency of family dinners and positive and negative dimensions of mental health in adolescents, and mediating role of communication between adolescents and parents | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic symptoms, emotional well-being | Parental communication, family meals |

| Microsystem (family) | Levin | 2012 | National (Scotland) | The association between adolescent life satisfaction, family structure, family affluence and gender differences in parent–child communication | To examine young people's life satisfaction in the context of the family environment | Life satisfaction | Family structure, family affluence and parental communication |

| Microsystem (family) | Dujeu | 2018 | National (Belgium) | Living arrangements after family split-up, well-being and health of adolescents in French-speaking Belgium | To identify the most favourable living arrangement to adolescent health and well-being in French-speaking Belgium. | Life satisfaction, multiple health complaints | Family structure |

| Microsystem (family) | Bjarnason | 2012 | International (36 countries) | Life satisfaction among children in different family structures: A comparative study of 36 western societies. | To examine differences in life satisfaction among children in different family structures in 36 western, industrialised countries | Life satisfaction | Family structure |

| Microsystem (family) | Steinbach | 2020 | International (37 countries) | Joint Physical Custody and Adolescents' Life Satisfaction in 37 North American and European Countries | To examine the association between physical custody arrangements and adolescent life satisfaction | Life satisfaction | Family structure/living arrangements |

| Microsystem (family) Intersectional | Zaborskis | 2018 | International (41 countries) | Gender and age differences in social inequality on adolescent life satisfaction: a comparative analysis of health behaviour data from 41 countries | To examine the gender and age differences in social inequality on life satisfaction among adolescents in 41 countries | Life satisfaction | Age, sex, family affluence |

| Microsystem (peers) | Matos | 2003 | National (Portugal) | Anxiety, depression, and peer relationships during adolescence | To examine correlates of depression and anxiety in a large, representative sample of adolescents. | Depression, anxiety | Peer relations |

| Microsystem (school) | Freeman | 2012 | International (3 countries) | The relationship between school perceptions and psychosomatic complaints: cross-country differences across Canada, Norway, and Romania | To examine the predictive value of school climate and peer support for psychosomatic complaints, perceived academic achievement, and school satisfaction in Canada, Norway, and Romania. | Psychosomatic complaints | Peer support, school climate |

| Microsystem (school) | Torsheim | 2001 | National (Norway) | School-related stress, support, and subjective health complaints among early adolescents: a multilevel approach | To investigate the relationship between shared psychosocial school environment and subjective health complaints | Subjective health complaints | School stress and support |

| Microsystem (school) | Danielsen | 2009 | National | School-related social support and students' perceived life satisfaction. | To examine the effect of school related social support from teachers, classmates, and parents on students' life satisfaction | Life satisfaction | School support |

| Microsystem (school) | Moor | 2014 | National (Germany) | Explaining educational inequalities in adolescent life satisfaction: do health behaviour and gender matter? International journal of public health, 59 (2), 309-317 | To investigate educational inequalities and life satisfaction of boys and girls. | Life satisfaction | Educational track |

| Microsystem (school) | Diseth | 2014 | National (Norway) | Autonomy support and achievement goals as predictors of perceived school performance and life satisfaction in the transition between lower and upper secondary school. | To investigate students' perceptions of their teachers' autonomy support, the students' personal achievement goals, perceived school performance, and life satisfaction | Life satisfaction | School support |

| Microsystem (school) | Sonmark | 2016 | International (2 countries) | Individual and Contextual Expressions of School Demands and their Relation to Psychosomatic Health a Comparative Study of Students in France and Sweden. | To investigate the association between school pressure and demands and mental health in 2 different school systems | Psychosomatic health complaints | School pressure |

| Microsystem (school) | Rathman | 2018 | National (Germany) | Is being a “small fish in a big pond” bad for students’ psychosomatic health? A multilevel study on the role of class-level school performance. | To investigate whether level of high-performing students in classroom is negatively associated with psychosomatic complaints of students who perceive themselves as poor performers. | Psychosomatic complaints | School classmate performance effects |

| Microsystem (school) | Nielsen | 2017 | International (2 countries) | School transition and mental health among adolescents: A comparative study of school systems in Denmark and Australia | To explore the influence of transition from primary to secondary schools in Australia versus no transition in Denmark by comparing age trends in students' school connectedness, emotional symptoms | Emotional symptoms from SDQ | School connectedness |

| Microsystem (school) | Volk | 2006 | National (Canada) | Perceptions of parents, mental health and school among Canadian adolescents from the provinces and the northern territories | To examine association between mental health and school achievement and enjoyment | Subjective health complaints | School achievement and enjoyment |

| Microsystem (school) | Saab | 2010 | National (Canada) | School differences in adolescent health and wellbeing: Findings from the Canadian Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Study | To assess the relationship between student- and school-level factors and student health and wellbeing outcomes | Emotional Wellbeing, and Subjective Health Complaints | School environment |

| Microsystem (school) | Garcia-Moya | 2015 | International (England and Spain) | Subjective well-being in adolescence and teacher connectedness: A health asset analysis |

To examine teacher connectedness in detail and its potential association with emotional wellbeing | Emotional wellbeing (KIDSCREEN) | Teacher – pupil relationship (connectedness) |

| Microsystem (school) | Levin | 2012 | National (Scotland) | Subjective health and mental well-being of adolescents and the health promoting school: A cross-sectional multilevel analysis | To examine the impact of the health promoting school (HPS) on adolescent well-being | Life satisfaction, multiple health complaints | Health promoting school status |

| Mesosystem | /////////// | //////// | ///////////////// | /////////////// | ///////////////////////////////// | /////////////////// | ////////////////// |

| Mesosystem (family and school) | Matos | 2006 | National (Portugal) | Family-school issues and the mental health of adolescents: post hoc analysis from the Portuguese National Health Behaviour in School aged children survey | To investigate the role of family and school in adolescent mental health | Anxiety/depression | Family communication |

| Mesosystem (school and family) | Moore | 2020 | National | Socioeconomic status, mental wellbeing and transition to secondary school: Analysis of the School Health Research Network/Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey in Wales | To examine mental health of students experiencing transition to secondary according to family affluence and school affluence | Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale |

School transition, family affluence |

| Mesosystem (school and family) | Nielsen | 2016 | National (Denmark) | Does school social capital modify socioeconomic inequality in mental health? A multi-level analysis in Danish schools | To examine if the association between socioeconomic position and emotional symptoms among adolescents is modified by school social capital |

Emotional symptoms | School social capital, family socioeconomic status |

| Mesosystem (family and peers) | Moreno | 2009 | International (36 countries) | Cross-national associations between parent and peer communication and psychological complaints. | To assess whether or not communication with parents and with peers is related to experiencing psychological complaints in an attempt to explore the hypotheses of continuity and compensation or moderation between contexts | Psychological complaints | Parental and peer communication |

| Mesosystem (family, school and peers) | Calmeiro | 2018 | National (Portugal) | Life Satisfaction in Adolescents: The Role of Individual and Social Health Assets | To explore the relationship between adolescents' life satisfaction and individual and social health assets. | Life satisfaction | Family and peer support, school connectedness |

| Mesosystem (family, school and peers) | M Moore |

2018 | National (Wales) | School, Peer and Family Relationships and Adolescent Substance Use, Subjective Wellbeing and Mental Health Symptoms in Wales: a Cross Sectional Study | To test the independent and interacting roles of family, peer and school relationships in predicting subjective wellbeing and mental health symptoms among 11–16 year olds in Wales | Life satisfaction, mental health symptoms | Family relationships, support from friends, school connectedness |

| Macrosystem | /////////// | /////// | ///////////////// | //////////////// | //////////////////////////////// | /////////////////// | /////////////////// |

| Macrosystem (trends) | Hagquist | 2010 | National (Sweden) | Discrepant trends in mental health complaints among younger and older adolescents in Sweden: An analysis of WHO data 1985–2005. Journal of Adolescent Health | To elucidate the time trends in self-reported mental health complaints (internalising problems) among school children in Sweden during a time characterized by economic downturns and upturns, with a focus on possible differences across grades and genders | Psychological health complaints | Secular trends |

| Macro (trends) | Gariepy | 2016 | National (Canada) | Trends in psychological symptoms among Canadian adolescents from 2002 to 2014: Gender and socioeconomic differences | To describe trends in psychological health symptoms in Canadian youth from 2002 to 2014 and examine gender and socioeconomic differences in these trends. | Psychological symptoms | Secular trends |

| Macrosystem (trends) | Hodacova | 2017 | National (Czech Republic) | Trends in life satisfaction and self-rated health in Czech school-aged children: HBSC study. | To describe trends in life satisfaction from 2002 to 2014 | Life satisfaction | Secular trends |

| Macrosystem (Trends) | Potrebny | 2019 | National (Norway) | Health complaints among adolescents in Norway: A twenty-year perspective on trends | To examine time trends in health complaints among adolescents in Norway between 1994 and 2014 | Health complaints | Secular trends |

| Macrosystem (trends) | Hogberg | 2020 | National (Sweden) | Gender and secular trends in adolescent mental health over 24 years – The role of school-related stress | To investigate whether trends in mental health are due to increasing amount of stressors in the school environment. | Psychosomatic symptoms | Secular trends |

| Macrosystem (trends) | Cavallo | 2015 | International (31 countries) | Trends in life satisfaction in European and North-American adolescents from 2002 to 2010 in over 30 countries. | To examine trends in life satisfaction according to age and gender | Life satisfaction | Secular trends |

| Macrosystem (cross-cultural differences) | Ravens-Sieberer | 2009 | International (38 countries) | Subjective health, symptom load and quality of life of children and adolescents in Europe | To examine cross-cultural differences in the prevalence of school children's subjective health types and the pattern of socio-demographic and socio-economic differences. | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic symptoms | Secular trends and country effects |

| Macrosystem (socioeconomic) | Rathman | 2015 | International (27 countries) | Macro-level determinants of young people's subjective health and health inequalities: A multilevel analysis in 27 welfare states | To investigate whether macro-level determinants are associated with health and socioeconomic inequalities in young people's health | Psychosomatic health complaints | Macro socioeconomic indicators |

| Macrosystem (socioeconomic) | Zaborskis | 2019 | International (41 countries) | Social Inequality in Adolescent Life Satisfaction: Comparison of Measure Approaches and Correlation with Macro-level Indices in 41 Countries | To investigate socioeconomic differences in wellbeing at macro-level | Life satisfaction | Macro socioeconomic indicators |

| Macrosystem (socioeconomic) | Levin | 2011 | International (35 countries) | National income and income inequality, family affluence and life satisfaction among 13 year old boys and girls | To investigate cross-national variation in the relationship between family affluence and adolescent life satisfaction, and the impact of national income and income inequality on this relationship | Life satisfaction | Macro socioeconomic indicators |

| Macrosystem (gender) | Torsheim | 2006 | International (29 countries) | Cross-national variation of gender differences in adolescent subjective health in Europe and North America. | To investigate cross-national consistency and variation of gender differences in subjective health complaints | Subjective health complaints | Macro gender equality index |

| Macrosystem (gender) | De Looze | 2018 | International (34 countries) | The happiest kids on earth. Gender equality and adolescent life satisfaction in Europe and North America. | To examine whether societal gender equality can explain the observed cross-national variability in adolescent life satisfaction | Life satisfaction | Macro gender equality index |

| Macrosystem (policy) | Minguez | 2017 | International (10 countries) | The role of family policy in explaining the international variation in child subjective well-being. | To examine to what extend family policies can explain the variability of subjective child well-being components in different European countries | Life satisfaction | Macro family policies |

| Macrosystem and Individual | Boer | 2020 | International (29 countries) | Adolescents' Intense and Problematic Social Media Use and Their Well-Being in 29 Countries | To examine whether intense and problematic social media use (SMU) is independently associated with adolescent well-being; and whether these associations varied by the country-level prevalence of intense and problematic SMU. | Life satisfaction, psychological complaints | Country level SMU, individual level SMU |

| Macrosystem and microsystem | Ottova | 2012 | International (34 countries) | The Role of Individual-and Macro-Level Social Determinants on Young Adolescents' Psychosomatic Complaints | To examine the social determinants of psychosomatic complaints in young adolescents | Psychosomatic health complaints | Family-, peer- and school-related factors as well as country level determinants (Human Development Index [HDI]) |

| Macrosystem and microsystem | Dierckens | 2020 | International (17 countries) | National-Level Wealth Inequality and Socioeconomic Inequality in Adolescent Mental Well-Being: A Time Series Analysis of 17 Countries | To examine the association between national wealth inequality and income inequality and socioeconomic inequality in adolescents' mental well-being at the aggregated level. | Life satisfaction, psychological and somatic symptoms | Country income and wealth inequality; family affluence |

| Macrosystem and microsystem; intersectional | Kern | 2020 | International (33 countries) | Intersectionality and Adolescent Mental Well-being: A Cross-Nationally Comparative Analysis of the Interplay Between Immigration Background, Socioeconomic Status and Gender | To investigate mental well-being from an intersectional perspective – ie consequences of membership in combinations of multiple social groups and in relation to national context (immigration and integration policies, national-level income, and gender equality). | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic health complaints | Family affluence, gender, migrant status; country indices of income, gender equality and migrant intergration |

| Macrosystem (trends) and microsystem (school) | Cosma | 2020 | International (36 countries) | Cross-National Time Trends in Adolescent Mental Well-Being From 2002 to 2018 and the Explanatory Role of Schoolwork Pressure | To investigate cross-national time trends in adolescent mental well-being and the extent to which time trends in schoolwork pressure explain these trends | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic health complaints | Secular trends, schoolwork pressure |

| Macrosystem (trends) and microsystem (family) | Elgar | 2015 | International (34 countries) | Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002–2010: a time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. | To examine trends in health and socioeconomic inequalities in health. | Life satisfaction, physical (somatic) and psychological symptoms | Macroeconomic indicators (mean income and mean income inequality), family affluence |

NOTE: Different authors use a variety of different terms for the same mental health survey measures in the case of Multiple Health Complaints comprising 4 psychological and 4 somatic complaints. In different papers the following alternative terms have been used: psychosomatic symptoms, psychosomatic health complaints, subjective health complaints, subjective health. In some papers only the 4 psychological complaints are used and various terms applied including: psychological symptoms, psychological health complaints.

As Table 2 shows, the scale and sub-scales have also been given other names by different authors - so while the underlying concepts have been the same, the terminology used has varied. As well as subjective health/subjective health complaints, other terms used include multiple health complaints, psychosomatic symptoms, psychosomatic health complaints, subjective health complaints, subjective health. In some papers only the 4 psychological complaints are used and various terms applied including: psychological symptoms, psychological health complaints.

Table 3 (web supplement) provides a chronology of mental health terms used in paper titles. In addition to mandatory items, some papers include findings on optional package measures including from: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997); KIDSCREEN (Erhart et al., 2009; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2014); the Center for Epidemiologic Studies’ Short Depression Scale (CES-D-R 10) (Bradley et al., 2010), the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1994) and the WHO (Five) Well-Being Index (Topp et al., 2015). Additionally, aspects of social and psychological health and well-being including loneliness, sense of coherence and spirituality have been introduced as optional areas in HBSC and are included in our review.

Table 3.

Chronology of mental health terms used in selected papers.

| Year | Mental health measures included |

|---|---|

| 2001 | Subjective health complaints |

| 2003 | Depression, anxiety |

| 2004 | Life satisfaction, depressive mood |

| 2006 | Subjective health complaints |

| 2006 | Anxiety/depression |

| 2006 | Subjective health complaints |

| 2006 | Somatic health complaints, depression |

| 2008 | Life satisfaction, health complaints |

| 2009 | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic symptoms |

| 2009 | Confidence, happiness, helplessness and feeling left out, multiple health complaints (MHC) |

| 2009 | Psychological complaints |

| 2009 | Life satisfaction |

| 2010 | Psychological health complaints |

| 2010 | Emotional Wellbeing, and Subjective Health Complaints |

| 2010 | Life satisfaction |

| 2010 | Psychological symptoms |

| 2010 | Life satisfaction, subjective health complaints |

| 2010 | Multiple health complaints |

| 2011 | Life satisfaction |

| 2011 | Life satisfaction |

| 2011 | Depression |

| 2011 | Life satisfaction, Multiple Health Complaints |

| 2011 | Multiple health complaints |

| 2011 | Subjective health complaints |

| 2011 | Life satisfaction |

| 2012 | Psychosomatic health complaints |

| 2012 | Life satisfaction, multiple health complaints |

| 2012 | Psychosomatic complaints |

| 2012 | Life satisfaction |

| 2012 | Life satisfaction |

| 2013 | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic symptoms, emotional well-being |

| 2013 | Psychosomatic symptoms |

| 2013 | Emotional well-being (life satisfaction) |

| 2014 | Life satisfaction |

| 2014 | Life satisfaction |

| 2014 | Life satisfaction |

| 2014 | Psychological complaints |

| 2015 | Psychological complaints, life satisfaction, self-confidence, helplessness, and body image |

| 2015 | Life satisfaction, physical (somatic) and psychological symptoms |

| 2015 | Life satisfaction |

| 2015 | Psychosomatic health complaints |

| 2015 | Emotional wellbeing (KIDSCREEN) |

| 2015 | Life satisfaction |

| 2015 | Life satisfaction |

| 2015 | Psychological and somatic symptoms |

| 2015 | Psychological symptoms |

| 2015 | Life satisfaction, distress |

| 2016 | Psychological symptoms |

| 2016 | Emotional symptoms |

| 2016 | Psychosomatic health complaints |

| 2016 | Life satisfaction |

| 2016 | Life satisfaction |

| 2016 | Self-esteem, social competence and self-efficacy |

| 2016 | Psychological symptoms |

| 2016 | Social dysfunction (GHQ), anxiety and depression |

| 2016 | Multiple health complaints |

| 2016 | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic symptoms |

| 2016 | Psychosomatic complaints and emotional problems |

| 2017 | Life satisfaction |

| 2017 | Life satisfaction |

| 2017 | Emotional symptoms from SDQ |

| 2017 | Psychosomatic symptoms and life satisfaction |

| 2017 | Psychosomatic health complaints |

| 2017 | Spiritual well-being |

| 2017 | Psychosomatic health complaints |

| 2017 | Life satisfaction |

| 2017 | Confidence, happiness, psychological health complaints |

| 2018 | Life satisfaction |

| 2018 | Multiple health complaints |

| 2018 | Life satisfaction |

| 2018 | Psychosomatic complaints |

| 2018 | Psychosomatic health complaints |

| 2018 | Psychosomatic symptoms |

| 2018 | Life satisfaction, multiple health complaints |

| 2018 | Life satisfaction |

| 2018 | Subjective health complaints |

| 2018 | Life satisfaction |

| 2018 | Life satisfaction, mental health symptoms |

| 2018 | Life satisfaction |

| 2019 | Psychological symptoms |

| 2019 | Psychological symptoms |

| 2019 | Life satisfaction |

| 2019 | Emotional problems and emotional well-being |

| 2019 | Life satisfaction, multiple health complaints |

| 2019 | Life satisfaction |

| 2019 | Health complaints |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction, psychological problems |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction and KIDSCREEN Health related quality of life |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction |

| 2020 | Feel low, feel nervous (2 items from psychosomatic symptoms scale) |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic complaints |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction |

| 2020 | Psychosomatic symptoms |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction |

| 2020 | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction |

| 2020 | Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale |

| 2020 | Psychosomatic symptoms |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction, psychological complaints |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction, psychological and somatic symptoms |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic health complaints |

| 2020 | Life satisfaction, psychosomatic health complaints |

NOTE: Different authors use a variety of different terms for the same mental health survey measures in the case of Multiple Health Complaints comprising 4 psychological and 4 somatic complaints. In different papers the following alternative terms have been used: psychosomatic symptoms, psychosomatic health complaints, subjective health complaints, subjective health. In some papers only the 4 psychological complaints are used and various terms applied including: psychological symptoms, psychological health complaints.

Determinants of mental health

In this section, each paper is allocated to a system level, according to the focus of the paper, i.e. whether it primarily examines associations between determinants and mental health at the individual, microsystem, mesosystem or macrosystem level. In some papers, multiple levels are examined, for example, macro and individual level. These are identified in Table 2 (web supplement), under the highest level in the bio-ecological framework. Key findings of each paper are briefly presented; however, the evidence is not critiqued or evaluated as this is beyond the scope of the scoping review.

Individual level

Individual characteristics

Age

While this has been a topic for the HBSC International Reports previously mentioned, there are very few academic papers that directly address the issue of age differences in mental health. One using data from Scotland finds that between 1994 and 2008, younger adolescents scored more favourably on measures of confidence, happiness, helplessness and feeling left out than older adolescents (Levin et al., 2009).

Pubertal status

Age at menarche is included in most HBSC surveys as a mandatory item and international papers have been produced on timing of menarche in relation to family structure (Steppan et al., 2019) and overweight/obesity (Currie, Ahluwalia, et al., 2012). However, to date there are no papers on the association between pubertal timing and mental health.

Sex/gender

In selected papers comparing the mental health of girls and boys, both sex differences and gender differences are referred to, with the terms often used interchangeably. Levin et al. (2009) compare mental health of girls and boys in Scotland between 1994 and 2006. They report that, boys score more favourably on measures of confidence, happiness, helplessness and feeling left out than girls; and multiple health complaints are more prevalent among girls than boys.

A Belgian study explored gender differences in psychological health complaints (feeling low, irritability/bad temper, nervousness, and sleeping difficulties) and the mediating role of well-being factors - life satisfaction, self-confidence, helplessness, and body image. These four well-being factors together explained more than half of the female excess in feeling low. After full adjustment, only gender differences in sleeping difficulties among 13–15-year-olds remained significant (Savoye et al., 2015).

Native/migrant status

Questions about country of birth and country of parents’ birth are used for the identification of migrant adolescents and comparisons to be made between migrant groups and between migrant and native adolescents.

Comparison of non-migrant v migrant

In an Israeli study, mental well-being of native Israeli youth is associated with the quality of their relationships with parents, teachers and peers. However, for immigrant adolescents, a positive school environment (parental support at school, teacher support and peer relationships) predicted better mental health (Walsh et al., 2010).

Another Israeli study compares first- and second-generation immigrant adolescents from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) and Ethiopia, examining psychosomatic symptoms, and host/heritage identities as mediators of the relationship between discrimination and aggressive behaviour/substance use. Discrimination leads to a weaker host identity and increased psychosomatic symptoms, associated with substance use and aggressive behaviour (Walsh et al., 2018).

A cross-national study of 10 countries compared the well-being of migrant compared to native adolescents. Once differences in gender, age and family affluence are taken into account, immigrant children do not significantly differ from their peers in their life satisfaction in most countries (Molcho et al., 2010). In contrast, a Swedish study comparing subjective health complaints (SHC) of native versus adolescents of ‘foreign extraction’ find an increased risk of SHC among girls with a foreign background compared with girls with a Swedish background. No such differences were seen among boys (Carlerby et al., 2011).

Differences between migrant categories

Adolescent immigrants to Italy from western Europe have lower levels of health complaints and higher life satisfaction than those from Eastern European and non-Western/non-European countries (Borraccino et al., 2018).

Comparing the psychological well-being of Polish and Asian immigrant youth in Iceland, compared to their native peers, less life-satisfaction and more distress was reported in all non-native groups compared with natives with outcomes more negative for youth of mixed ethnic origin (Runarsdottir et al., 2015).

Sexual orientation

Some countries included questions about sexual orientation in their national surveys.

In a Dutch study, same-sex attracted (SSA) adolescents reported lower levels of life satisfaction, higher levels of psychosomatic complaints and emotional problems than heterosexual adolescents. Not yet attracted (NYA) adolescents reported equal levels of life satisfaction and psychosomatic complaints as heterosexual adolescents, but higher levels of emotional problems (Kuyper et al., 2016).

In Iceland, lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) adolescents were worse off across most of the psychosocial measures across the three surveys (2006, 2010 and 2014) as compared with adolescents of unknown sexual orientation (USO). However, the gap between LGB and USO adolescents appears to be closing, at least for the 2010 to 2014 change, suggesting that outcomes for LGB adolescents have improved compared to four years earlier (Thorsteinsson et al., 2017).

Adopted and non-adopted

Complex differences and similarities are found in a Spanish study of non-adopted and adopted (native and non-native, and country of birth among non-native adoptees) and generalities do not apply (Paniagua et al., 2020).

Farm-living and non-farm-living

In a study of adolescent girls in Canada it was found that those from farms in the most rural schools reported more positive mental health than non-farm girls (Pickett et al., 2020).

Intersectional influences

The intersectional effects of being a member of several demographic groups have been explored in a few papers. Within our bio-ecological framework papers on intersectional effects are mainly considered at the individual level but can also be considered at the individual/microsystem level, where family socioeconomic status is a determinant.

One paper examined gender and age differences in socioeconomic inequality (SEI) in life satisfaction (LS) among adolescents in 41 countries. Family affluence was significantly positively associated with higher adolescent LS in nearly all countries, among girls and boys and across ages. However, the gender and age differences in this association were inconsistent across countries (Zaborskis & Grincaite, 2018).

Kern et al. (2020) examined intersectional effects on mental health and also examined macro-level effects - this paper is discussed in a later section (Macro and micro level interactions).

Other aspects of health

Body weight

One study examined the relationship between perceptions of being overweight and mental health and how this has changed over time across HBSC surveys in different countries. Between 2002 and 2014, perceived overweight became more strongly associated with psychosomatic complaints in 4 countries among boys and in 12 countries among girls (Whitehead et al., 2017).

A recent study of Spanish adolescents, Baile et al. (2020) reported that those classified as obese, according to their Body Mass Index, have lower life satisfaction and health related quality of life as measured by the KIDSCREEN instrument.

Medicine use

One international study explored medicine use and mental health in 19 countries. It reported that medicine use was strongly positively associated with the frequency of health complaints; and the prevalence of both medicine use and health complaints was higher among girls than boys (Gobina et al., 2011).

Chronic conditions/disabilities

Two national papers from Portugal and one cross-national paper were found in the database that examined the relationship between chronic conditions and mental health.

One Portuguese study found that adolescents with disabilities had more psychosomatic symptoms than their nondisabled peers. Furthermore, disabled students who report better health were happier and more satisfied with their lives (Canha et al., 2016). Another compared Portuguese adolescents living without and with a chronic condition (CC), the latter reporting more psychosomatic symptoms/health complaints than their peers without a CC (Santos et al., 2015).

The cross-national study examined bullying and mental health among adolescents who have a disability or chronic illness (D/CI) compared to those who have not. A higher level of victimization was found among those with a D/CI and victims of bullying were more likely to report low life satisfaction and multiple health complaints. However, there were no differences in the associations between peer victimization and subjective health indicators according to the D/CI status (Sentenac et al., 2013).

Loneliness

Lyyra et al. (2018) in a Finnish study reported that loneliness was associated with psychological symptoms among girls and among 15-year-old students (Lyyra et al., 2018).

Spirituality

Spirituality, has a broad definition and relates to wisdom, compassion, the experience of joy in life, moral sensitivities and “connectedness” (Michaelson et al., 2016). A Slovak study found associations between spirituality and both health complaints and life satisfaction (Dankulincova Veselska et al., 2018).

Sense of coherence

Sense of coherence (SoC) is considered to be part of the concept of resilience, reflecting an individual's resistance in the face of stress (Nielsen & Hansson, 2007). One paper, using Norwegian data, and finds SoC had stress-preventive, stress-moderating and health-enhancing effects (Torsheim et al., 2001).

Risk and health behaviours

Smoking

Two studies explored smoking and mental health, both national, one from Ireland and the other from Norway. The Irish study found smokers were more likely to report lower life satisfaction and higher rates of health complaints than non-smokers (Evans et al., 2019). The Norwegian study examined the association between smoking and health complaints in surveys between 1994 and 2010 and across all surveys, health complaint scores were significantly higher for smokers. Females had higher prevalence of health complaints and this association was stronger among smokers compared with non-smokers (Braverman et al., 2016).

Alcohol use

In a Swiss study, ‘risky single occasion drinkers’ (RSODs) had lower life satisfaction and more depressive moods, with solitary RSODs being even less satisfied and more likely to have depression than social RSODs (Kuntsche & Gmel, 2004).

Cannabis use

In a study using data from the Netherlands, after adjusting for confounding factors, cannabis use was not found to be linked to internalising problems such as somatic health complaints and depression (Monshouwer et al., 2006).

Sexual behaviour

One paper examined the links between sexual behaviour and mental health using data from 5 countries, and found that early age at sexual initiation was not related to psychological/somatic symptoms among boys in any nation. However, girls from Poland and the US who had early age of sexual initiation were more likely to report symptoms (Madkour et al., 2010).

Bullying and violence

Six national papers and one cross-national paper emerged from the interrogation of the database that had a focus on mental health in relation to bullying/violence.

A recent US study found that peer victimization is associated with higher risk of feeling low and feeling nervous, although this risk is decreased by support from friends (Hong et al., 2020).

In a Spanish study, the moderating role of Sense of Coherence (SOC) in the association between bullying and mental health was examined. Adolescents with weak SOC were significantly more likely to suffer from bullying victimization and to suffer physical and psychological symptoms than adolescents with a strong SOC (García-Moya et al., 2014).

Bully victimization rates in Scotland increased between 1994 and 2014 for most age-gender groups and over this time, female (but not male) victims reported less confidence and happiness and more psychological complaints than their non-bullied counterparts (Cosma et al., 2017). In a Portuguese study, the effect of cyberbullying on girls was found to be different to boys, with girls more likely to report emotional symptoms, especially fear and sadness (Carvalho et al., 2018).

An Italian study found that being a victim of cyberbullying was positively associated with psychological and somatic symptoms, after controlling for traditional bullying victimization and computer use. Cyber victimization has similar psychological and somatic consequences for boys and girls (Vieno et al., 2015).