Abstract

Introduction

Nepal passed a comprehensive tobacco control law in 2011. Tobacco control advocates successfully countered tobacco industry (TI) interference to force implementation of law.

Aims and Methods

Policy documents, news stories, and key informant interviews were triangulated and interpreted using the Policy Dystopia Model (PDM).

Results

The TI tried to block and weaken the law after Parliament passed it. Tobacco control advocates used litigation to force implementation of the law while the TI used litigation in an effort to block implementation. The TI argued that tobacco was socially and economically important, and used front groups to weaken the law. Tobacco control advocates mobilized the media, launched public awareness campaigns, educated the legislature, utilized lawsuits, and monitored TI activities to successfully counter TI opposition.

Conclusions

Both tobacco control advocates and the industry used the discursive and instrumental strategies described in the PDM. The model was helpful for understanding TI activities in Nepal and could be applied to other low- and middle-income countries. Civil society, with the help of international health groups, should continue to track TI interference and learn the lessons from other countries to proactively to counter it.

Implications

The PDM provides an effective framework to understand battles over implementation of a strong tobacco control law in Nepal, a low- and middle-income country. The TI applied discursive and instrumental strategies in Nepal in its efforts to weaken and delay the implementation of the law at every stage of implementation. It is important to continuously monitor TI activities and learn lessons from other countries, as the industry often employ the same strategies globally. Tobacco control advocates utilized domestic litigation, media advocacy, and engaged with legislators, politicians, and other stakeholders to implement a strong tobacco control law. Other low- and middle-income countries can adapt these lessons from Nepal to achieve effective implementation of their laws.

Introduction

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) commits parties to implement evidence-based tobacco control policies, including restrictions on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS), protection from secondhand smoke, strong health warnings, tobacco taxes, and preventing tobacco industry (TI) interference with tobacco control.1 Several countries adopted tobacco control policies after ratifying the FCTC2–9 and the FCTC led to a measurable decline on tobacco consumption.10

The TI’s strategies to limit the FCTC’s impact include third party alliances, trade and investment agreements, litigation, and lobbying.7,11–17 The TI often succeeds in delaying, blocking, or weakening tobacco control policies, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where weak governance and institutions often make them vulnerable to TI influence.4,18 Civil society groups and advocates can overcome TI interference, particularly with national and international technical and financial support.7,13,19 While civil society and health advocates’ efforts to pass tobacco control policies have been documented,13,20 research on implementation is more limited.7,18

Nepal faced longtime political turmoil and conflict until stabilizing in 2006.21 Nepal ratified the FCTC in 2006 and enacted the Tobacco Product (Control and Regulatory) Act in 2011 to implement the FCTC.22,23 The law established 100% smokefree public places, banned TAPS, required pictorial health warning labels (PHWLs) occupying 75% of the pack (90% after a subsequent amendment in 2014), and instituted a health tax on all tobacco products.22,23 In 2019, the UN Development Program estimated that investing in FCTC implementation in Nepal would save nearly 84 000 lives and avert the loss of 121 billion Nepali rupees by 2033.24

The objective of this study is to describe how the TI attempted to block effective implementation of Nepal’s law and how tobacco control advocates countered these strategies.

Methods

We reviewed media reports from Nexis Uni (https://advance.lexis.com/) and retrieved tobacco policy documents from the websites of Nepal’s Health Ministry (MoH) (http://www.mohp.gov.np/), Supreme Court (http://supremecourt.gov.np/web/), Law Paper (http://nkp.gov.np/), WHO FCTC, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (CTFK) Tobacco Control Laws (http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/), and news articles from Google (https://www.google.com/). We searched the UCSF Truth Tobacco Documents Library but we did not find TI documents related to Nepal between 2011 and 2019. We searched for relevant media reports and articles published in Nepalese or English between April 2011 and July 2018 using standard snowball techniques.25 We started the searches with “Nepal,” “tobacco control,” “tobacco industry interference,” “tobacco legislation,” “tobacco ban,” “tobacco advertisement,” “tobacco health warnings,” “tobacco policy,” and “tobacco tax.” In June and July 2018, we conducted nine key informant interviews (one Parliament member, two policymakers, three tobacco control advocates, and three MoH officials). Interviews were recorded and transcribed; all interviewees consented verbally on the record. This study was approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

This study uses the Ulucanlar et al.26 Policy Dystopia Model (PDM), first developed to identify discursive and instrumental strategies the TI uses to counter marketing bans and taxation based on a systematic review of the literature. The discursive strategies are argument-based strategies the TI uses to exaggerate the potential cost of a proposed policy while denying or dismissing its potential benefits. Instrumental strategies are actions to influence policymakers and other stakeholders against regulating tobacco (Table 2). Our study expands use of the PDM by also using it to examine the tobacco control advocacy response strategies to industry discursive and instrumental strategies.

Table 2.

Using the Policy Dystopia Model26 to Understand Strategies Used to Undermine Comprehensive Tobacco Control Policy in Nepal and Counter Strategies Used by Tobacco Control Advocates

| Domain | Tobacco industry (TI) arguments | Tobacco control advocates’ strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Discursive (arguments-based) strategies | ||

| Unanticipated costs to economy and society | ||

| The economy | Policy will lead to job losses, less pay and will affect workers and their families. Policy will lead to loss of revenue. | Clarified TI’s misinterpretation of law through media. No provision in proposed bill to shut down any tobacco company. |

| Law enforcement | Policy will increase smuggling. Policy difficult to implement. | No such statistics available support TI claim. Informed legislators and politician against industry’s false claims. |

| The law | Policy prohibits fundamental public freedom to trade and conduct business. Policy violated trade agreements and free trade provisions. Policy is unfriendly to trade and agriculture, does not provide alternate income source for tobacco farmers. HWLs are against trademark act. | No such statistics available with TI claim. Advocates alerted legislators and politician to industry’s false claim through media. Agriculture ministry developed guidelines to help tobacco farmers switch crops. |

| Politics/Governance | HWLs are not applicable, not sufficient for trademark. 180-Day implementation period is impractical. | Policy is in line with the FCTC. Informed legislators and politician against TI’s false claim through media. |

| Social justice | Policy is unfair to trade or tobacco business. | False claim of TI. |

| Unintended benefits to underserving groups | Unknown. | Informed media that some politicians were supporting TI for their personal gain. |

| Unintended costs to public health | Unknown. | |

| Intended public health benefits | Policy will not work and is not needed. Policy is impractical and difficult to implement. | Policy is in line with the FCTC. Informed through media writing. HWLs are utilized by governments all over the world. |

| Expected tobacco industry costs | Industry will lose business, will hurt economy and jobs, short term implementation of PHWLs costly. |

| Tobacco industry strategies | Tobacco advocates’ strategies | |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumental (activity-based) strategies | ||

| Coalition management | Coordinated with different tobacco groups, TI employee union, different associations. Used front groups and U.S. Chamber of Commerce to help weaken, block, and prevent implementation of the law. Met politicians and legislators to push for weaker law. | Met with politicians and MPs, highlighted TI and legislators engagements in the media. Nationwide awareness campaigns. Worked with civil society groups and stake holders, got support from international health groups. Met with restaurant and hotel associations, and labor unions. |

| Information management | Policy information collected from legislatures, MPs, and politicians. Disseminated TI contribution through press meets/conferences. | Met and alerted politicians against TI false claims. |

| Direct involvement and influence in policy | Gifting and financial support to the politicians, civil society, bureaucrats, judges, lawyers. Lobbied key politicians and health minister. Provided draft bill. Lobbied politicians, bureaucrats and health advocates to involve in government policy writing and implementation. | Monitored TI activity. Lobbied Prime Minister, key politicians and used media advocacy to counter corrupt behavior by politicians, ministers, legislatures, and bureaucrats. |

| Litigation | Filed lawsuits to weaken and delay tobacco control law implementation. Submitted letter to the Prime Minister, Finance Minister, Health Minister, and head of the political party. | Filed lawsuits to force implementation of the law. |

| Illicit trade | Unknown. |

FCTC = Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; MPs = Members of Parliament; PHWLs = pictorial health warning labels.

Results

Parliament passed the Tobacco Product (Control and Regulatory) Act on April 11, 2011, which the President approved on May 9, 2011, effective August 7, 2011, with the PHWL rule effective November 4, 2011.22,23

TI Activities to Prevent the President From Signing the Approved Bill

On April 12, 2011, the day after Parliament passed it, the TI lobbied politicians and ministers to stop the bill from reaching the president for his signature.27–30 The TI unsuccessfully demanded amendments to the bill, expressing concerns about PHWLs, the ban on smoking in public places and restrictions on sales to minors.31 After the President signed the bill into law, the TI said it would comply with restrictions on tobacco sales to pregnant women and minors, but that other restrictions, such as a ban on smoking in public places and PHWL, were inappropriate.32 The TI claimed that the public places’ smoking violated smokers’ rights and would be difficult to implement. The TI itself was not disobeying the law, but spreading misinformation that would lead to businesses and people to disobey the law. In December 2013,33,34 as it did in 200621 and 2009,22 the Supreme Court clarified that it is the state’s responsibility to restrict tobacco product use in public places, therefore the ban was appropriate.

Industry Argues There Were Unanticipated Costs to Economy and Society

After failing to prevent the President from signing the bill into law, the TI, consistent with the discursive strategy of PDM, used their employees, coalitions, and front groups to fight implementation27,35 (Tables 1 and 2). It claimed that the law would cause industry closures, job losses (claiming that over 600 000 people would lose their jobs), lower pay, increase cigarette smuggling from neighboring countries, costing revenue and jobs, affect legal tobacco business, and was impractical.

Table 1.

Key Players and Their Roles in Tobacco Control in Nepal (2011–2018)

| Role and involvement | |

|---|---|

| Government Organizations | |

| National Health Education, Information and Communication Center, Ministry of Health (MoH). | Develop, implement, and monitor tobacco control policy and programs. Nepal government liaison office for tobacco control. |

| Funding: CTFK/Bloomberg: (1) Fund to establish tobacco control program and secure passage of policy by the Parliament (2010–2012); (2) strengthening of tobacco-control efforts in Nepal through effective implementation and enforcement of tobacco control policies (2013–2015). Nepal government, and UKAID. | |

| Non-government Organizations—tobacco control | |

| 1. Nepal Cancer Relief Society (NCRS) | Advocacy for tobacco control policy and programs from 1982 onward. Case filed in the Supreme Court for policy implementation. |

| Funding: CTFK/Bloomberg: Smoke Free Kathmandu Valley: Towards implementation of 100% Smoke Free environments in the health and hospitality sectors (2012–2013). Receive funding from Nepal government, local resources and other international agencies after 2013. | |

| 2. Health and Environment Awareness Forum Nepal (HEAFON) | Advocacy for tobacco control policy from 2007 to 2014. |

| Funding: Nepal National Health Fund, and WHO. | |

| 3. Resource Centre for Primary Health Care (RECPHEC) | Advocacy for tobacco control policy and programs from 1991 onward. |

| Funding: CTFK/Bloomberg (2007–2010) for policy advocacy and other agencies. Did not receive funding for tobacco control after 2010 but used other funds for tobacco control program. | |

| 4. Action Nepal | Advocacy for tobacco control policy from 2008 onward. Case filed in the Supreme Court for 90% HWLs implementation. |

| Funding: CTFK/Bloomberg: (1) Enforcement of a 75% Pictorial Health warning in Nepal: mobilization of media and policy makers (2014–2015); (2) policy and media action to facilitate implementation of 90% Pictorial Health warning in Nepal (2015); (3) building government commitments to improve taxation on tobacco products and ensure effective implementation a 90% Pictorial Health warning in Nepal (2016–2017); (4) advancing tobacco control in Nepal (2018–2020). | |

| International Organizations | |

| The Union/International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease | Technical support to MoH. |

| World Health Organization | Technical support to MoH. |

| CTFK/Bloomberg Philanthropies (Bloomberg Initiative Grant) | Financial support to MoH and other NGOs. |

| The FCTC Secretariat | Technical support to MoH and other government sectors. |

| Key tobacco industry actors | |

| Surya Nepal Private Limited (SNPL) | Filed case in court and interference with tobacco control policy. A subsidiary of ITC India and BAT, since 2000 Nepal’s largest tobacco company. |

| Seti Cigarette Factory Ltd | Filed case in court and interference with tobacco control policy. |

| Perfect Blends Nepal Pvt Ltd (PBNPL) | Filed case in court and interference with tobacco control policy. |

| Gorkha Lahari Pvt. Ltd | Filed case in court and interference with tobacco control policy. |

| Other tobacco groups | |

| Shrestha Bidi Factory Mira Bidi Factory Arbinda Bidi Factory Anuska Production Pvt. Ltd Chetrapal Store (retailer) Sruti Churot Karkhana Ltd SNPL Bara employees Union Nepal Multinational Company Trade Union Santalal Banda (represented a tobacco farmer) | Filed case in the Supreme Court against the government (writ no. 068-WS-0022, and others). |

| Front groups and allies | |

| Nepal Multinational Company Trade Union Tobacco Farmer Association Tobacco Retailers Association Tobacco Industry Labor Union Hotel and Restaurant Labor Union Hotel Association Nepal Distributor Association Nepal Retailers Association Nepal Pan Traders Association Nepal Super Market Association Restaurant Association Nepal Tobacco Association | Supported tobacco industry against tobacco control law. |

| Transnational tobacco industry allies | |

| U.S. Chamber of Commerce | Opposed the law’s implementation. |

| Samriddhi Foundation86 | Coalition against plain packaging. |

In particular, the industry argued the law would cause job losses or lower pay to their employees’ labor unions.27,35 The President of Nepal’s Multinational Companies Workers Union (including tobacco) repeated these arguments, saying the law would significantly reduce tobacco sales and harm thousands of workers.36 The TI’s front groups (Table 1) requested the Prime Minister, Finance Minister, Health Minister, and heads of major political parties save the jobs of over 600 000 people by not implementing the law.32

On August 21, 2011, the Managing Director of Surya Nepal Private Limited (SNPL, a subsidiary of ITC, India, with 70% of market share21,22), argued that the law would increase cigarette smuggling from neighboring countries, costing revenue and jobs.37 Other tobacco manufacturers and a few Members of Parliament (MPs) argued the law would affect legal tobacco business, and was impractical.37 The TI’s arguments (Table 2) were the same used when it attempted to block the law in Parliament.27–30,38,39

Tobacco control advocates, with the help from the international health community, organized seminars, and meetings with hotel associations and labor unions, used media advocacy, and educated parliamentarians, key political leaders, and different ministers to counter the TI’s economic claims.

Tobacco Control Advocates’ Strategy

The Nepal Cancer Relief Society (NCRS), Health and Environment Awareness Forum Nepal (HEAFON), Resource Centre for Primary Health Care (RECPHEC), and Action Nepal (Table 1) organized a nationwide awareness campaign in August 2011 to support the law’s implementation, distributing colorful pamphlets with messages and pictures highlighting major points of the law to the public.40 The National Health Education Information Communication Center (NHEICC, under MoH), WHO and CTFK supported the campaign financially and technically.28,39,41 The Speaker of Parliament inaugurated the campaign.42 NCRS organized meetings with restaurant and hotel associations and labor unions to discuss health impacts of tobacco, the law, and how the TI was lobbying against the law.35

TI Direct Involvement and Influence in Policy

The TI built relationships with politicians, legislatures, ministers, and bureaucrats who supported industry positions (Table 2). The TI lobbied the personal assistant of the Chief of the Maoist Party, asking him to urge the Health Minister to delay implementation, especially the 75% PHWLs, and lobbied Health Minister, Rajendra Mahato, to block the directives27,30,43 which the MoH was required to publish to implement the law, including size and color of pictures, color of text, and PHWL location.44,45

The industry attempted to block, weaken, and delay these regulations to prevent implementation of the law. Tobacco control advocates lobbied Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai, and worked with the media to pressure Mahato, who had been delaying the implementation directives under pressure from the TI, telling the Prime Minister that they were going to file a complaint in the Supreme Court.27,30,35 Following these advocacy efforts, on November 5, 2011, Mahato approved the implementing directives for PHWLs.

The TI was already preparing to litigate against the PHWL immediately after the approval of directives to further delay implementation or defeat the directives. Tobacco control advocates were aware of this industry strategy and also used litigation to pressure for immediate implementation before the industry sued. While the health advocates eventually prevailed, the litigation delayed implementation of the final rules until 2014.

Both Sides Litigate

On November 8, 2011, NCRS and Forum for Protection of Consumer Rights Nepal (FPCRN) filed a case in the Supreme Court against the government demanding that sales and purchases of tobacco products not meeting the PHWLs criteria specified in the law be suspended.35,46 On November 9, 2011, the Supreme Court (Judges Kamal Narayan Das) issued an interim order directing the TI to stop importing or exporting tobacco products, and retailers to stop sales of tobacco products, without the 75% PHWLs and ordered the government to seize noncompliant tobacco products at customs.35,46

On November 17, 2011, SNPL filed a case in the Supreme Court against the government arguing that the law could not be implemented immediately because doing so would cause heavy losses on products already packaged and that the PHWLs were not consumer friendly. In response, the Supreme Court (Judges Tahir Ali Ansari) issued an interim order on November 21, 2011 ordering both sides (TI and government) to appear in court on November 23, 2011.47 The court made a final decision in December 2013 (discussed below).

By January 2012, 12 additional cases were filed in the Supreme Court by TI and protobacco groups (Figure 1) against the law.48,49 TI ignored several provisions of the law, including PHWLs, and the ban on sales to minors until January 2014.

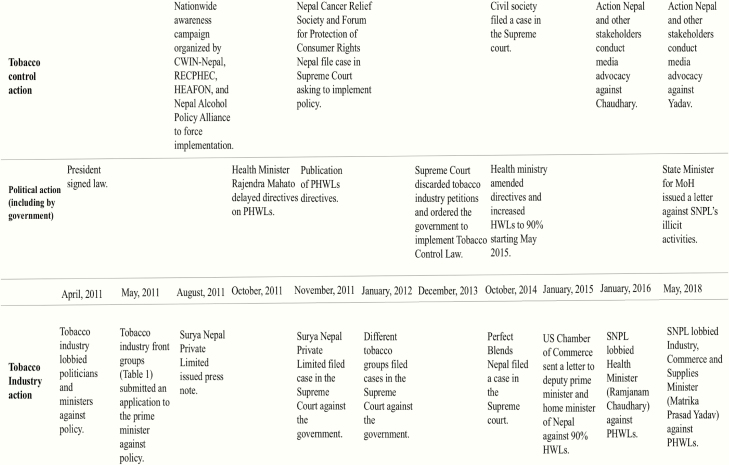

Figure 1.

Timeline of tobacco control events in Nepal between 2011 and 2018.

In its court case the TI claimed the tobacco control law: (1) was unconstitutional; (2) prohibited the public’s fundamental freedom to conduct trade and business; (3) violated existing trade agreements and free trade provisions; (4) was unfriendly to trade and agriculture because it did not provide alternative income sources for tobacco farmers; (5) required reporting to MoH of the amount of nicotine was not rational for tobacco farmers; (6) would negatively affect the economy and employment; (7) required a 75% PHWL that was not in line with the FCTC, would not work, and that the remaining 25% package cover was insufficient for displaying trademarks as secured by the trademark act, thus demanding that the PHWL be revised to 30% and not implemented for at least 3 years); (8) only allowed 180 days for implementation, which was impractical and should be extended to 18 months; (9) should permit TI representation in tobacco control regulatory committees; (10) imposed an impractical to ban sales within 100 m of public places such as schools, old age homes, government buildings, bars, and public parks (Table 2).33,34,48,49

Consistent with the PDM, the TI used well-established arguments, including that the law would increase illicit trade (law enforcement), that it was not consistent with domestic or international trade and investment law, it was not applicable and not liberal to tobacco business (politics and governance), and unfair to trade or tobacco business (social justice) and that the law would not work (intended public health benefits) (Table 2).

The Supreme Court Upholds the Law

Tobacco control advocates continued to educate politicians and legislators and used public awareness campaigns and media advocacy to expose the TI’s false claims.

In January 2012, civil society groups including HEAFON, NCRS, RECPHEC, and Action Nepal requested Prime Minister Bhattrai help with the hearing process in court.27,29,30 In addition, HEAFON and Action Nepal organized meetings with lawyers, health professionals, media groups to generate public awareness, and lobbied Nepal’s Attorney General to accelerate the Supreme Court hearing.27,30 In December 2013, NCRS organized a meeting with HEAFON, RECPHEC, Human Rights Organization of Nepal, FPCRN, Nepal Retailers Association (not related to tobacco), and lawyers to discuss the case50 and pressure judges to quicken the hearing.49,51

A key informant reported that the TI offered money to NGOs (especially NCRS and FPCRN) and their lawyer when the cases were pending in the Supreme Court. After the offer, FPCRN became passive during litigation but NCRS remained supportive.35 The TI allegedly had financial links with judges, possibly delaying the hearing process for 25 months27,30,52 and allowing the industry to increase efforts to influence politicians, legislators and civil society.27,30

In December 2013, the Supreme Court (Judges Kalyan Shrestha, Tark Raj Bhatta and Gyanendra Bahadur Karki) dismissed all the TI’s cases and ordered the government, including the office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers, MoH, Education Ministry, and Information and Communication Ministry to immediately implement the law.33,34,53 The Supreme Court ruled that “It is the State’s responsibility to compel the [tobacco] company to put the health warning labels in the packets or parcels, to regulate the tobacco trade and to prohibit its use in public places. Nepal’s Constitution secure the rights to live in a clean environment and tobacco smoke pollutes the environment which violate the basic rights of non-smokers to live in clean environment.” 33,34 Specifically the Court ruled that (1) the tobacco control law was constitutional and complied with the FCTC, including the PHWLs; (2) cases filed by the TI were against the public welfare and the law was in the public interest; (3) the TI must inform the public of the negative effects of tobacco; (4) MoH should develop regulations based on the law Parliament passed; (5) there was no rationale for granting the additional time TI demanded to implement PHWLs; (6) no one could violate the public’s rights to live in healthy environment; and (7) all noncompliant tobacco products should be removed from the market (Figure 1).33,34,48,54

In response to the court order, the MoH sent a letter to the Industry, Commerce and Supplies Ministry and Department of Customs asking them to completely close the import, production and distribution of tobacco products that were not compliant with the law.55 After the Supreme Court decision, the government implemented the law, with PHWLs effective from April 2014.45

TI Opposition to 75% PHWLs

The TI continued opposing the 75% PHWLs even after losing in the Supreme Court.45,56 In June 2014 the Secretary General of Nepal Tobacco Association held a press conference arguing that the international practice for PHWLs was 30%–40% and Nepal’s 75% requirement would mislead consumers.56 The Director of the Department of Commerce and Supply Management under the Industry Ministry, supported the industry, saying that the government should maintain tobacco products packaging uniformity between domestic and imported cigarette packs.56 This argument was misleading because the law imposed the same requirements for domestic and imported packs.

MoH Increases PHWLs

Action Nepal organized meetings in June 2014 with the Home Affairs, Industry, and Ministries, political leaders and media to facilitate implementation of 75% PHWLs.27 NCRS, Action Nepal, and The Union requested Health Minister Khagraj Adhikari increase the PHWLs to 90%.27 He and Secretary of Health Shanta Bahadur Shrestha showed a high-level political commitment to tobacco control and to increasing the PHWLs.27,36,39,57 On October 30, 2014, the MoH with the support of NCRS, Action Nepal, and The Union amended the directive on PHWLs to 90%,58,59 effective May 15, 2015,23,58,60,61 using the power conferred by the Tobacco Control law (Figure 2).

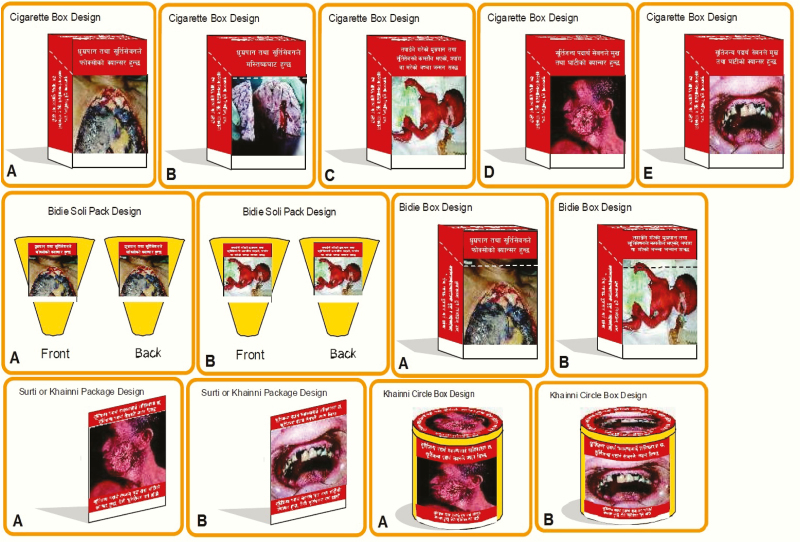

Figure 2.

Pictorial health warnings covering 90% of the both side of packs required in Nepal after May 2015.58

TI supporters argued that Adhikari’s decision to increase PHWLs would impact business and lobbied politicians to pressure him not to implement the change from 75% to 90%.63 The TI lobbied the Health Minister, political leaders, ministers, and bureaucrats against 90% PHWLs arguing that featuring five pictures on one pack was impossible to implement.27,29,35,39 In fact, the law only required one of five rotating pictures to appear on each pack.

Tobacco companies have longstanding ties with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (USCC) and the International Chamber of Commerce.63 In Nepal, as elsewhere, the USCC actively worked against tobacco control.15,63,64 The USCC senior vice president for Asia wrote the Deputy Prime Minister and Home Affairs Minister in January 2015 stating that “we would strongly encourage the MoH to reconsider this regulation’s implementation taking into account the unusual speed by which it was issued and the likely negative perception this could generate with the international business community. Specifically, we encourage outreach to business and industry in ongoing consultations regarding policies, sound policy implementation, and improved governance.” 65,66

After these efforts failed, the TI proposed 85% PHWLs. The MoH rejected the proposal, and health advocates ran a media campaign to support of the 90% PHWLs,27,62 which took effect in May 2015, as required. As a result, MoH received the Bloomberg Philanthropies Award for Global Tobacco Control during the 16th World Conference on Tobacco or Health in March 2015.67

Adhikari and Shrestha also planned to increase PHWLs gradually to 100% and implement plain packaging.28,39 These policies were not pursued because Adhikari was replaced by a new coalition government in October 2015 and Shrestha transferred to another ministry.

Consistent with the PDM, TI and civil society used information management and influence to affect policy (Table 2). The TI lobbied politicians and misinterpreted the provision of PHWLs and was countered by tobacco control advocates.

Continuing Opposition to 90% PHWLs

The USCC continued to lobby against the 90% PHWL. In June 2015, it emailed the chief secretary of the government warning “Nepal not to devise strict anti-tobacco measures and the proposal would negate foreign investment and invite instability.” 68

Perfect Blends tobacco company had filed a case in the Supreme Court on January 29, 2015 against the 90% PHWLs. The Supreme Court did not issue an order, but even with the case pending, Perfect Blends implemented the 90% PHWLs in May 2015.69 While the case was pending, other tobacco companies lobbied different judges, lawyers, and political leaders to stop the 90% PHWLs.27 Action Nepal and lawyer Hutaraj Koirala separately filed a case in the Supreme Court in March 2016 demanding the rejection of case filed by Perfect Blends and full implementation of the 90% PHWLs. SPNL claimed that while the case was pending, and until the Supreme Court make a decision, it would not apply the 90% PHWLs. As of May 2019 the cases filed by Perfect Blends, Action Nepal and Hutaraj Koirala remained pending,27 but all tobacco companies, except SNPL, implemented 90% PHWLs.

SNPL lobbied Prime Minister Sushil Koirala, Chief Secretary of the Government Lilamani Paudel, and Secretary of Industry Ministry Surya Silwal against the 90% PHWLs from May 2015 through February 2016. All three subsequently wrote separate letters to the Health Minister stating that the MoH must involve TI people when implementing tobacco control policies.27,29,35 Paudel and Silwal also urged that the 90% PHWLs be reconsidered due to the devastating earthquake on April 25, 2015, although they had no authority to give direction to the MoH.27,29,35,39 Action Nepal organized meetings with different MPs, civil society groups, and bureaucrats, and organized media advocacy to generate pressure on TI’s political allies to prevent them from implementing the SNPL’s requests.27,29,35,70

SNPL lobbied Ramjanam Chaudhary, the new Health Minister appointed in October 2015, to decrease PHWLs from 90% to 75%.27,39 Chaudhary verbally ordered Health Secretary Shanta Bahadur Shrestha to initiate the process to decrease PHWLs.27 Health advocates used media advocacy, with stories on Chaudhary favoring and receiving money from the TI to foster opposition.27,29,35 In addition, advocates successfully lobbied Shrestha to support 90% PHWLs. Without Shrestha’s support, Chaudhary could not change the 90% PHWLs.27

Similarly, in May 2018, SNPL lobbied Industry, Commerce and Supplies Minister (Matrika Prasad Yadav) through his personal assistant to reduce PHWLs.27 Action Nepal organized meetings with legislators, media, bureaucrats, and Kathmandu Metropolitan City Mayor to pressure Yadav. The media highlighted his support of the TI.27,71 In response, State Minister for MoH Padma Aryal issued a letter to SNPL opposing its activities.27 SNPL replied that it was obeying government rules and requesting inclusion of a TI representative in the policy process.27,28,39 As of May 2019, SNPL was applying 75% PHWLs and government was not penalizing it.

Discussion

Tobacco control advocates in Nepal secured implementation of the 2011 tobacco control law by engaging politicians, legislators, lawyers, the media, a national and international network, and using litigation. The TI delayed the bill’s implementation for almost 3 years but failed to stop it. A supportive Supreme Court decision and political commitment from some ministers, bureaucrats, and MPs helped implementation. As elsewhere, the TI used litigation, front groups and allies to influence bureaucrats and politicians to delay implementation of the law.11,17,18,72

Law enforcement agencies were not specifically funded and directed to monitor and enforce implementation and penalize the violators, leading to lax enforcement. The industry worked to undermine the law by promoting smokers’ rights and making tobacco products widely available to make it easier for people to smoke anywhere and for minors to obtain the products.

In Nepal, as in Nigeria,72 the PDM26 helped systematically assess TI discursive (argument-based) and instrumental (action-based) strategies to oppose tobacco control and tobacco control advocates’ strategies to counter the industry. TI discursive strategies focused on claims of unanticipated costs to the economy and society and aggressively targeted at weakening and delaying HWLs (Table 2). TI instrumental strategies centered mostly on direct involvement and influence in policy and litigation. Tobacco control advocates responded reactively with discursive counter arguments and proactively with instrumental actions, including litigation, media advocacy, and lobbying to support implementation of the tobacco control law.

The PDM is an evolving model to both analyze TI activities and plan strategies to counter the TI. Given the fact that the industry is fearful of diffusion of best practices spreading regionally and globally, our findings suggest that tobacco control advocates can use the PDM to proactively anticipate and counter TI interference in relation to where the industry acts most aggressively. The PDM can also guide advocates and governments in developing media advocacy and campaigns,72,73 and in contextualizing the TI strategies.

TI tactics in Nepal are similar to those documented across the world.6,7,11,14,18,21,22,26,72, 74–76 According to FCTC Article 5.3, parties must ensure that they implement measures to prevent TI interference. Such measures are facilitated by the fact that the TI’s responses are predictable, but Article 5.3 implementation remains a gap among FCTC parties.16,18 Nonetheless, being a Party to the FCTC supported Nepal’s tobacco control advocates arguments, and the Supreme Court decision mentioned compliance with the FCTC as a justifiable principle used by the government. In 2017, Nepal became one of the countries participating in WHO’s FCTC203077 project, which aims to accelerate implementation of the FCTC and support countries toward the Sustainable Development Goals. Being part of FCTC2030 will support maintaining progress made to date as well as addressing gaps, including implementation of Article 5.3. The UNDP tobacco control investment case in Nepal24 will continue to provide evidence against the TI’s fallacious economic arguments. As a party to the FCTC Nepal will continue to benefit from the international tobacco control network and receive legal and technical assistance.78 Nonetheless, the TI is expected to continue efforts to prevent full implementation of the law.

Implications for Nepal and Other Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Consistent with advocates’ experiences elsewhere, international financial and technical support facilitated tobacco control advocacy in Nepal, including policy formulation and implementation, and defending against TI interference.5–7,13,14,72,76,79–81 As in Uruguay, multisectoral coordination was a key element for success of tobacco control advocates.7

The TI used the media to disseminate several strategic arguments, but advocates successfully used media advocacy to counter its claims.17,82–84 It is important to systematically document TI strategies to counter them. Governments also need to invest in media campaigns highlighting TI interference and creating awareness among their citizens on different provisions of the tobacco control law.

As elsewhere,17,85,86 the TI established alliances with retailers, trade associations, employee unions, consumer groups, and trade unions, including the International Chambers of Commerce, to oppose the law’s implementation.82,87,88 Additionally, the TI maintained relationships with key legislators and politicians in its ongoing efforts to prevent and weaken the law’s implementation89–93 by fostering disagreements between governmental departments.17,18,75,91,94–99 This strategy succeeded in weakening legislation in several countries17,94,95,100–102 but failed in Nepal. Nepal illustrates the importance of civil society establishing relationships with different ministries, monitoring their relationships with the TI, and being prepared to denounce these relationships, and to use litigation.

Civil society groups in Nepal sued the government in the Supreme Court to implement comprehensive policy. The TI also sued the government to block the comprehensive policy as they did in other low- and middle-income countries.5,7,13,14,20,103–107 The TI used lawsuits to delay, increase legal costs, overturn, or weaken the public health law,108 and successfully pressed the court to delay the court hearing21 and implementation. Ultimately, these tactics failed because of active counter-intervention by health advocates.

Limitations

We collected publicly accessible and available information. Older government records were unavailable to verify some claims made by key informants. We used newspaper information to verify key informants’ material. TI documents for this period (2011–2018) were not available in the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Library to provide detailed information on TI internal discussions.

Conclusion

The PDM offers a template to systematically document and counter TI strategies. Nepal’s case adds to an emerging body of research on tobacco control law implementation.109 Strong political commitment, being a party to the FCTC, and in some cases, the courts, are necessary at all levels to have a successful tobacco control policy.1,7,110,111 Policy coherence and multisectoral coordination are essential for FCTC implementation.7,112–114 TI strategies and tactics are well known and countries need to prepare in advance to defend tobacco control legislation and its implementation.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as references numbered 51–114, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Supplementary data are available at Nicotine & Tobacco Research online.

Acknowledgments

We thank all key informants who provided valuable information and our colleagues Dan Orenstein, Candice Bowling, Tanner Wakefield, Amy Hafez, and Lauren Lempert for feedback on the manuscript.

Note: References 51–114 are in the supplemental text file.

Funding

This research was funded by National Cancer Institute grant CA-087472. The funding agency played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research. Approval number 10-01262.

Authors’ Contributors

DNB developed the idea for this study, carried out the data collection and analysis, wrote and revised the manuscript. SG developed the idea for this study, revised and edited the manuscript. SB and EC contributed to the final conceptualization of the study, and revised and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42811/1/9241591013.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hiilamo H, Glantz S. FCTC followed by accelerated implementation of tobacco advertising bans. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):428–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Uang R, Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Accelerated adoption of smoke-free laws after ratification of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):166–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Implementation of effective cigarette health warning labels among low and middle income countries: state capacity, path-dependency and tobacco industry activity. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124(0):241–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sankaran S, Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Implementation of graphic health warning labels on tobacco products in India: the interplay between the cigarette and the bidi industries. Tob Control. 2015;24(6):547–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. Costa Rica’s implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: overcoming decades of industry dominance. Salud Publica Mex. 2016;58(1):62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. Defending strong tobacco packaging and labelling regulations in Uruguay: transnational tobacco control network versus Philip Morris International. Tob Control. 2018;27(2):185–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fong GT, Chung-Hall J, Craig L; WHO FCTC Impact Assessment Expert Group Impact assessment of the WHO FCTC over its first decade: methodology of the expert group. Tob Control. 2019;28(suppl 2):s84–s88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gravely S, Giovino GA, Craig L, et al. Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: an association study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(4):e166–e174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chung-Hall J, Craig L, Gravely S, Sansone N, Fong GT. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the Impact Assessment Expert Group. Tob Control. 2019;28(suppl 2):s119–s128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(suppl 1):117–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gonzalez M, Glantz SA. Failure of policy regarding smoke-free bars in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(1):139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uang R, Crosbie E, Glantz SA. Tobacco control law implementation in a middle-income country: transnational tobacco control network overcoming tobacco industry opposition in Colombia. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(8):1050–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crosbie E, Sebrié EM, Glantz SA. Strong advocacy led to successful implementation of smokefree Mexico City. Tob Control. 2011;20(1):64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crosbie E, Eckford R, Bialous S. Containing diffusion: the tobacco industry’s multipronged trade strategy to block tobacco standardised packaging. Tob Control. 2019;28(2):195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fooks G, Gilmore AB. International trade law, plain packaging and tobacco industry political activity: the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Tob Control. 2014;23(1):e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weishaar H, Collin J, Smith K, Grüning T, Mandal S, Gilmore A. Global health governance and the commercial sector: a documentary analysis of tobacco company strategies to influence the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, Bialous SA, Jackson RR. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):1029–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gneiting U. From global agenda-setting to domestic implementation: successes and challenges of the global health network on tobacco control. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(suppl 1):i74–i86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. The importance of continued engagement during the implementation phase of tobacco control policies in a middle-income country: the case of Costa Rica. Tob Control. 2017;26(1):60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhatta DN, Crosbie E, Bialous S, Glantz S. Tobacco control in Nepal during a time of government turmoil (1960–2006). Tob Control. 2019:tobaccocontrol-2019-055066. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bhatta DN, Crosbie E, Bialous S, Glantz S. Exceeding WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) obligations: Nepal overcoming tobacco industry interference to enact a comprehensive tobacco control policy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019:ntz177. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ministry of Health and Population. Tobacco Product (Control and Regulation) Act.Nepal: Ministry of Health; 2011. https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Nepal/Nepal-TPRegs2011.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24. UNDP. Investment Case for Tobacco Control in Nepal: The Case for Investing in WHO FCTC Implementation in Nepal. New York, NY: One United Nations Plaza; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mamudu HM, Hammond R, Glantz S. Tobacco industry attempts to counter the World Bank report curbing the epidemic and obstruct the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(11):1690–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB. The policy dystopia model: an interpretive analysis of tobacco industry political activity. PLoS Med. 2016;13(9):e1002125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chand AB. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Joshi KP. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mulmi SL. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kandel TP. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Himalayan Times. Anti-tobacco Bid May Go Up in Smoke 2011. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/267a476d-bbe5-425c-b478-da184f299434/?context=1516831. Accessed July 23, 2019.

- 32. Himalayan Times. Traders Unite Against Tobacco Bill 2011. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/0920ab0d-ea7f-4706-b082-62ed55a98ece/?context=1516831. Accessed July 23, 2019.

- 33. Supreme Court Nepal. Decision no. 9120—certiorari/mandamus 2013. Nepal Law Mag. 2014. http://nkp.gov.np/full_detail/21. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- 34. Supreme Court Nepal. Decision no. 9132—mandamus 2013. Nepal Law Mag. 2014. http://nkp.gov.np/full_detail/33. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- 35. Rajkarnikar D. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Himalayan Times. Workers Against Tobacco Bill 2011. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/f29df62b-306b-497a-b16a-390175c621e1/?context=1516831. Accessed July 23, 2019.

- 37. Sarkar S. ITC Subsidiary Faces Double Whammy in Nepal Cambridge, MA: IANS; 2011. http://twocircles.net/2011aug21/itc_subsidiary_faces_double_whammy_nepal.html. Accessed September 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thapa Gk. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thapaliya R. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Himalayan Times. Anti-tobacco Campaign Launched 2011. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/18a02320-3ff5-491b-aa77-373310e1069b/?context=1516831. Accessed July 23, 2019.

- 41. Shrestha M. Interview with Dharma Bhatta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42. My Republica. Smoking in Public to Be Banned from Sunday 2011. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/af8166bf-1b2f-4c51-8c79-17f2dd582c3f/?context=1516831. Accessed July 23, 2019.

- 43. Gautam M. Anti-tobacco directive gathers dust on health minister’s table. The Kathmandu Post 2011. http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2011-10-25/anti-tobacco-directive-gathers-dust-on-health-ministers-table.html. Accessed June 12, 2018.

- 44. Ministry of Health and Population. Tobacco Products (Control and Regulation) Regulation Nepal: Ministry of Health; 2011. https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Nepal/Nepal-TPA.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ministry of Health and Population. Directives for Printing and Labeling of Warning Message and Graphics in the Boxes, Packets, Wrappers, Cartons, Parcels and Packaging of Tobacco Products. Nepal: Ministry of Health; 2011. https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Nepal/Nepal-PLDirective.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 46. The Kathmandu Post. Implement Anti-tobacco Directives.2011. http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/printedition/news/2011-11-09/implement-anti-tobacco-directives.html. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- 47. Ekantipur Report. Anti-tobacco directives: Supreme Court order to stay enforcement. The Kathmandu Post 2011. http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2011-11-18/anti-tobacco-directives-supreme-court-order-to-stay-enforcement.html. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- 48. Tobacco Control Laws. Nepal Health Warnings Challenge 2014. https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/litigation/decisions/np-20140101-nepal-ghws-case. Accessed December 15, 2018.

- 49. Ramakant B. Nepal Gearing to Protect Public Health from Tobacco Industry Interference Lucknow, India: Citizen News Service; 2014. http://www.citizen-news.org/2014/10/nepal-gearing-to-protect-public-health_27.html. Accessed January 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Himalayan Times. Smoking in Public. 2013. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/e594db86-ebde-4431-8148-5b2da82a71c6/?context=1516831 Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.