Abstract

An intra-abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) belongs to a rare group of diseases initially described as an inflammatory pseudotumour. Even though it is seen more often in children, its incidence in adults is even rarer. Clinical presentations can vary depending on its site and inherent tumour properties. The colon is an uncommon site for IMT and pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) as its dominant clinical presentation is even rarer. A 27-year-old woman presented with PUO. She was evaluated under the department of internal medicine before undergoing an 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan. This showed an intensely enhancing descending colon mass. An image-guided biopsy of this lesion was reported as IMT. She underwent a left hemicolectomy and complete excision of the tumour, following which her symptoms resolved completely. The patient has been disease-free at a 6-month follow-up and is asymptomatic at 1 year.

Keywords: surgery, surgical oncology, pathology, colon cancer

Background

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours (IMTs) are a group of rare neoplasms that have an unclear aetiology and various modes of presentation. The age group most commonly affected are children and young adults with a predisposition for the female gender.1 This neoplasm is composed of myofibroblastic cells with a background of inflammatory infiltrate comprising of plasma cells, lymphocytes and eosinophil.2 3 The lungs are the most commonly affected site.3 The gastrointestinal tract, especially colonic IMTs, are rarely reported in the literature.2–4 The symptoms of the disease are generally non-specific and depend on the location of the tumour. Due to these reasons, the diagnosis of this condition poses a challenge to the treating physicians. The initial presentation of a colonic IMT as ‘pyrexia of unknown origin’ (PUO) is unique and rare.

Case presentation

A 27-year-old woman presented with complaints of high grade, intermittent fever for 3 months. There were no localising symptoms for the fever. She had no bowel-related complaints. Her clinical examination was unremarkable. She was initially evaluated at another centre and was diagnosed with PUO. She was referred to our centre for further evaluation and management. She was admitted under the department of internal medicine where she was documented to have an intermittent, high-grade fever.

Investigations

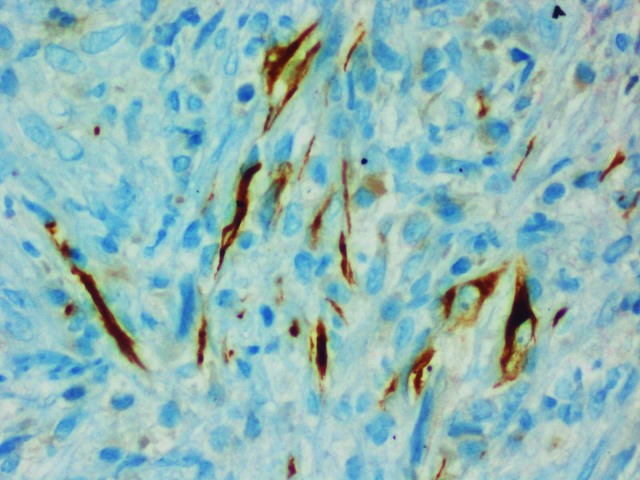

She was evaluated for PUO and all initial evaluations were unremarkable. Ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen/pelvis was normal. Since 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET-CT) scan has been shown to have a role in the evaluation of PUO, she was evaluated with the same.5 This showed a large, well defined intensely enhancing (standard uptake value of 21.62) retroperitoneal mass in the left lumbar region (figure 1). Corresponding CT images showed a well-defined 43×39 mm sized mass in the left lumbar region indenting the proximal descending colon with no luminal compromise (figure 2). Colonoscopy showed no mucosal abnormality. A USG-guided biopsy from this mass showed cores of a tumour comprising of interlacing fascicles of spindle cells with elongated nuclei exhibiting nuclear hyperchromasia, mild nuclear pleomorphism, inconspicuous nucleoli and moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic activity was inconspicuous. The intervening stroma showed few eosinophils (figure 3A–C). In the immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis, the tumour cells were focally positive for anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1 (ALK-1) (figure 4), desmin (figure 5) and smooth muscle actin (SMA) and negative for CD117, CD15 and CD30. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of the IMT was made.

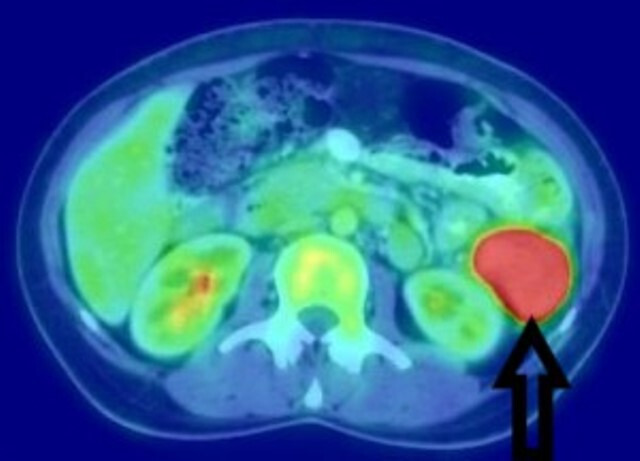

Figure 1.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan showing an intensely enhancing retroperitoneal mass in the left lumbar region.

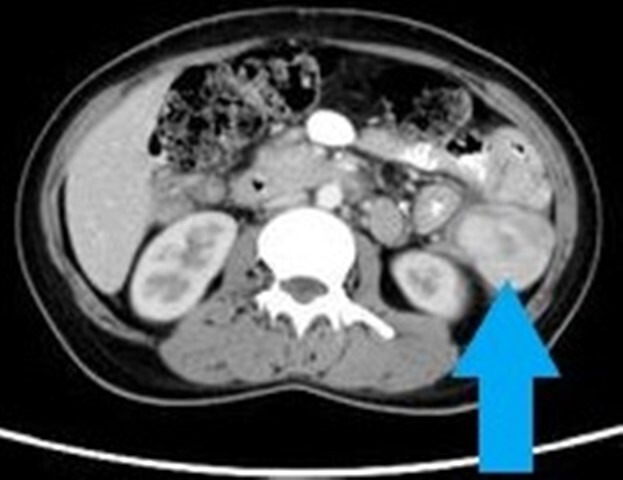

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the abdomen/pelvis showing a well-defined, intensely enhancing lesion in the left lumbar retroperitoneal region, indenting the proximal descending colon.

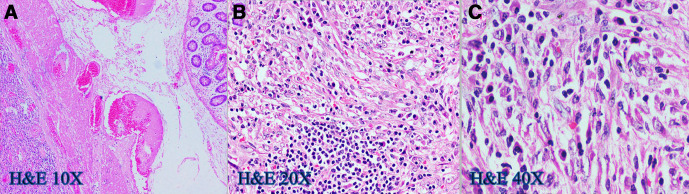

Figure 3.

(A–C) H&E slides showing sheets of polygonal cells with moderate nuclear pleomorphism, vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli and moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm and admixed lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils and foamy histiocytes.

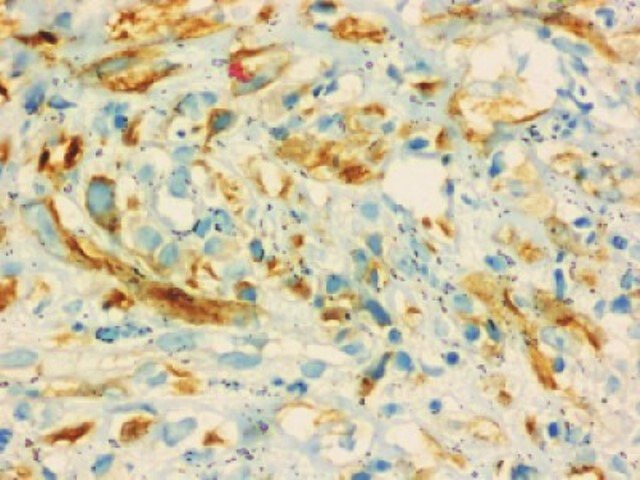

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry slide (40×) showing tumour cells with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1 (ALK-1) positivity.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry slide (40×) showing tumour cells with desmin positivity.

Differential diagnosis

She was a 27-year-old woman who presented with high-grade fever for the past 3 months without any localising signs. The differentials considered initially were infective conditions like tuberculosis, malaria, brucellosis and infective endocarditis, non-infectious inflammatory conditions and neoplastic conditions.

Baseline blood investigations showed mild anaemia (haemoglobin 84 g/L), a mild rise in alkaline phosphatase (142 U/L) with no other abnormalities. Her serial blood cultures were negative. An echocardiogram done did not show any vegetation ruling out infective endocarditis. The possibility of tuberculosis was considered higher in the list of differentials given its endemicity in our setting, but she did not have any respiratory symptoms or signs. Her induced sputum smear, Quantiferon-Gold test and CECT (contrast-enhanced CT) scan of the thorax were normal. The possibility of lymphoma and other haematological malignancies was considered but her cell lines were normal except for the mild anaemia, and the bone marrow examination was reported normal. She underwent a gynaecological evaluation which was also normal. Given female sex and young age, the possibility of autoimmune disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis was considered but the workup for both was negative. Given the persisting fever with all the medical workup and baseline imaging being unremarkable, it was decided to do an 18F-FDG-PET-CT scan which showed the intensely enhancing retroperitoneal mass; most likely to be arising from the descending colon.

Clinical differentials considered at this time were:

Hemangiopericytoma.

Extra-colonic gastrointestinal stromal tumour.

Castleman’s disease.

Paraganglioma.

IMT.

She underwent a USG-guided biopsy of the mass which confirmed the diagnosis of an IMT.

Treatment

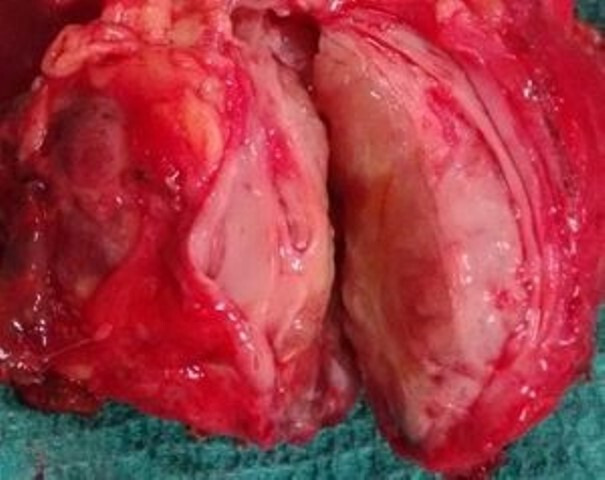

She was transferred under the Department of General Surgery and underwent a laparotomy. Intraoperatively, there was a 7×5 cm, hard, fleshy, exophytic mass arising from the proximal descending colon. The tumour appeared to be adherent to a focal area of Gerota’s fascia with desmoplasia. There was no infiltration of the surrounding structures or evidence of colonic luminal narrowing. The rest of the large bowel and small bowel were normal. USG-guided needle biopsy tract was not visualised intraoperatively. She underwent a left hemicolectomy. The part of the Gerota’s fascia where the tumour was focally adhered by desmoplasia was additionally resected to ensure complete circumferential clearance. Bowel continuity was restored with a hand-sewn colo-colic anastomosis. Cut opened surgical specimen is shown in figure 6.

Figure 6.

A cut section of the surgical specimen showing a fleshy tumour.

Surgical histopathology was consistent with an IMT of the colon. The maximum tumour dimension was 6.5 cm. The tumour was located in the subserosa and was <0.1 cm from the marked serosal margin in a focal area. Proximal and distal resection margins were free and there were nine regional lymph nodes with reactive changes. Additionally, submitted fibro-fatty tissue and ‘Gerota’s fascia’ had no tumour cells.

Her case was discussed in the multidisciplinary tumour board meet. No adjuvant therapy was advised since the resection was felt complete. She was advised closed follow-up because of the high risk of recurrence despite complete excision.

Outcome and follow-up

She remained afebrile in the postoperative period and was discharged well on the sixth postoperative day. At her first follow-up visit a week later, she was asymptomatic. Follow-up at 6 months was also uneventful. She was lost to follow-up then. However, at just more than a year now following the treatment, we had a telephonic conversation with the patient and she is asymptomatic. She is being counselled to come for the disease assessment at the earliest.

Discussion

An IMT was first described in 1939 by Dr Brunn.6 It was described previously as plasma cell granuloma, inflammatory pseudotumour, atypical fibromyxoid tumour, histiocytoma and fibroxanthoma.7

An IMT is a type of tumour comprised of differentiated myofibroblastic spindle cells, infiltrated by many inflammatory cells and is usually accompanied by conspicuous lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates and a myxoid stromal background. IMT is classified as an intermediate neoplastic lesion in the fourth edition of the WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone (2013).8

The primary IMT is a very rare neoplasm in adults and the exact aetiopathogenesis of the tumour continues to remain a mystery.9 The disease was initially thought to primarily involve children and young adults and the lungs were considered to be the most common organ involved.10 However, it can arise from any site ranging from the oral cavity to the central nervous system.11–15

Intra-abdominal IMT is rarely reported, most commonly being found in the stomach.16 17 Colorectum ranks fifth among the intra-abdominal sites preceded only by the liver and biliary tract, spleen, peritoneum and stomach. The most common site of colonic IMT is in the right colon.2 Jejunum-ileum, duodenum, pancreas and oesophagus were also reported.17 Gastrointestinal IMTs can have wide variations in clinical presentation. Commonly, they present with an abdominal mass with related compressive symptoms such as abdominal pain or obstruction.18 It can also present with acute intraperitoneal bleed.18 Luminal bleeding is rare due to the extra mucosal location of these tumours.3 It can also rarely present with peritoneal dissemination.19 Colonic IMT can present with abdominal pain, abdominal mass, weight loss, chronic hematochezia, diarrhoea, fever, intestinal obstruction, colo-colic or ileocolic intussusception.3 18

Colonic IMT with PUO as the sole presentation is rare.5 20 21 Our patient had a chronic fever as the only presenting complaint and never had any abdominal or other systemic complaints. Due to this, she was initially worked up extensively at two different centres under physicians. This resulted in a delayed diagnosis and treatment. The systemic manifestations including fever that may occur in this disease entity are due to an overproduction of interleukin-6 (IL-6).22 There are reports of cases where the IL-6 returned to normal levels postoperatively.23 24

The colonoscopy in a colonic-IMT often shows an intraluminal soft tissue mass with normal overlying mucosa and may mimic a gastrointestinal stromal tumour. In certain cases, the mucosa may show areas of erosions, ulcerations or hyperaemia and the biopsy in that case often shows chronic inflammation.2 3 5 In a diagnosed case of colonic-IMT, the role of colonoscopy is limited. The management is not altered by a colonoscopy in such situation. In our patient, the colonoscopy was performed before the USG-guided biopsy of the lesion and it showed no intraluminal mass. The radiological findings in a colorectal IMT are variable and non-specific. They can appear either as a well-demarcated, heterogeneous solitary mass or as non-capsulated, ill-defined, protruding or infiltrative mass.2 3 25 In our patient, the initial imaging modalities used for evaluation of the PUO included a CECT scan of thorax and USG abdomen/pelvis. If a CECT scan of abdomen/pelvis was performed as part of the initial evaluations, the colonic lesion could have been identified earlier and a subsequent PET-CT avoided. A CECT scan of the thorax/abdomen/pelvis should be considered as initial imaging of choice in patients with PUO. If the baseline imaging does not provide clues to the diagnosis, an 18-FDG-PET or a hybrid 18-FDG-PET-CT should be considered, although its use may be limited by availability.26

The histological appearance of gastrointestinal IMT is very similar to that of soft tissue IMT. Characteristic histopathological features of IMT are myofibroblastic proliferation, a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate distributed among the tumour cells and a myxoid background stroma. Three architectural patterns have been described in IMT—myxoid hypocellular pattern, a cellular fascicular or nested pattern and a sclerotic, hyalinised pattern.15 IHC plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis. Due to their myofibroblastic differentiation, IMTs are positive for SMA in 80%–90% of cases and express desmin and calponin in 60%–70%, although reactivity for these markers is often focal.27 28

It has been a matter of debate whether IMT is a tumour or inflammatory condition and also whether it is benign or malignant. Some authors propose a neoplastic origin, whereas others believe that it results from an immunological response to tissue injury from infections (Epstein-Barr-virus, Herpes virus, Campylobacter), surgery, trauma, radiotherapy or drugs.29 30 Improved molecular techniques, however, have identified that a subset of these tumours is neoplastic in nature, harbouring translocations of the ALK gene.31 32 Cytogenetic studies have identified rearrangements on the ALK gene on chromosome 2p23, clonal chromosomal abnormalities, DNA aneuploidy and the role of oncogenic viruses in the pathogenesis of IMT. Clonal abnormalities of the ALK gene were first expressed in anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), in which nearly 60% of the cases contain the translocation of the ALK gene.33 The most common fusion protein in ALCL (NPM-ALK) has not been identified in IMT, but the TPM3- ALK, ATIC-ALK and CLTC-ALK fusion proteins have been identified, thus representing translocation-derived chimeric tyrosine kinases driving both mesenchymal and lymphoid neoplasms.32–34 IHC can help in the detection of IMT in nearly 50% of the cases, though some series report a rate as high as 70%.35 ALK gene rearrangement in IMT can be detected with fluorescence in situ hybridisation or reverse transcription-PCR.36

The primary treatment choice of these tumours is complete surgical excision followed with long-term surveillance.37 Radiotherapy and chemotherapy have also been tried as an adjunct with no real reported benefit. The most common chemotherapy agents used are cisplatin, doxorubicin and methotrexate.38 39 Targeted therapy with ALK and mesenchymal-epithelial transition tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Crizotinib, is used to treat aggressive tumours that express ALK positivity, including unresectable ones.40

IMTs in the abdomen including the retroperitoneum generally have a more aggressive behaviour with high local recurrence rate, local invasion and metastasis. However, colorectal IMTs generally have a favourable prognosis with low recurrence in comparison to extra-colonic abdominopelvic locations.41

The overall recurrence rate of IMT is 18%–40% and is more common in extrapulmonary lesions (25%–37%), especially in those with size more than 8 cm and those with local invasion.41 42 Primary abdominopelvic IMTs have a high risk of a local recurrence rate of 25%–85%.42 Aggressive behaviour or progression can be predicted from a combination of atypia, aneuploidy and p53 expression.43 Malignant transformation can be predicted by the presence of tumour necrosis, prominent nucleoli, vesicular chromatin and spindle cell to atypical polygonal cell transition.44

Our patient had ALK gene-positive with histopathological features representative of IMT. She underwent a left hemicolectomy and had an uneventful postoperative period. She did not receive any adjuvant therapy as per the decision of our multidisciplinary cancer board meeting.

Learning points.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours are commonly seen in children and are rare in adults.

Colonic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour in adults is rarely reported and can be kept among the non-medical differentials for ‘pyrexia of unknown origin’.

The colonoscopy often shows normal mucosa and the radiological studies are non-specific.

The diagnosis is confirmed with histopathology including immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis.

The primary treatment modality with the least recurrence rate is complete surgical resection.

Acknowledgments

Dr Mayur Suryawanshi, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, India for the histopathology and IHC photomicrographs. Department of General Medicine Unit II, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, India for the initial management of the patient.

Footnotes

Contributors: VVC: concept, data collection and drafting the manuscript. SS: concept, drafting the manuscript, editing of the manuscript and review of the final manuscript. BR: concept, editing of the manuscript and review of the final manuscript. SC: editing of the manuscript, review of the final manuscript, overall patient management and guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Shi H, Wei L, Sun L, et al. Primary gastric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 5 cases. Pathol Res Pract 2010;206:287–91. 10.1016/j.prp.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim EY, Lee IK, Lee YS, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in colon. J Korean Surg Soc 2012;82:45–9. 10.4174/jkss.2012.82.1.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raffaeli E, Cardinali L, Fianchini M, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the transverse colon with synchronous gastrointestinal stromal tumor in a patient with ulcerative colitis: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2019;60:141–4. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S-H, Kim J-H, Min BW, et al. Exophytic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the stomach in an adult woman: a rare cause of hemoperitoneum. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:136–9. 10.3748/wjg.14.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou RU, Xiang J, Chen Z, et al. Fever of unknown origin as a presentation of colonic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in a 36-year-old female: a case report. Oncol Lett 2014;7:1566–8. 10.3892/ol.2014.1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunn H. Two interesting benign lung tumors of contradictory histopathology; remarks on necessity for maintaining chest tumor registry. J Thorac Surg 1939;9:119–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffin CM, Fletcher JA. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour : Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F, World health organization of classification of tumors: pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press, 2002: 91–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al. The fourth edition of the World Health Organiztion (WHO) Classifcation of tumours of soft tissue and bone, Mae-stro 38330. Saint-Ismier, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: where are we now? J Clin Pathol 2008;61:428–37. 10.1136/jcp.2007.049387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inamura K, Kobayashi M, Nagano H, et al. A novel fusion of hnRNPA1 – ALK in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of urinary bladder. Hum Pathol 2017;69:96–100. 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.JP W, Yunis EJ, Fetterman G, et al. Inflammatory Pseudo-tumours of the abdomen: plasma cell granulomas. J Clin Pathol 1973;26:943–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scully RE, Mark EJ, McNeely BU. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 13-1984. fever and anemia in a young man with a pelvic mass. N Engl J Med 1984;310:839–45. 10.1056/NEJM198403293101308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pisciotto PT, Gray GF, Miller DR. Abdominal plasma cell pseudotumor. J Pediatr 1978;93:628–30. 10.1016/S0022-3476(78)80903-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Day DL, Sane S, Dehner LP. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the mesentery and small intestine. Pediatr Radiol 1986;16:210–5. 10.1007/BF02456289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, et al. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor) a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:859–72. 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dial DH. Plasma cell granuloma-histiocytoma complex : Daile DH, Hamma SP, Pulmonary pathology. New York: Springer Verlag, 1988: 889–93. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Höhne S, Milzsch M, Adams J, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor (ipt) and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT): a representative literature review occasioned by a rare IMT of the transverse colon in a 9-year-old child. Tumori Journal 2015;101:249–56. 10.5301/tj.5000353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovach SJ, Fischer AC, Katzman PJ, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. J Surg Oncol 2006;94:385–91. 10.1002/jso.20516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosse K, Ott C, Biegner T, et al. 23-Year-Old female with an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the breast: a case report and a review of the literature. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2014;74:167–70. 10.1055/s-0033-1360185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souid AK, Ziemba MC, Dubansky AS, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in children. Cancer 1993;72:2042–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katara AN, Chandiramani VA, Dastur FD, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of ascending colon presenting as PUO: a case report. Indian J Surg 2004;66:234–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshizaki K, Matsuda T, Nishimoto N, et al. Pathogenic significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6/BSF-2) in Castleman’s disease. Blood 1989;74:1360–7. 10.1182/blood.V74.4.1360.1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azuno Y, Yaga K, Suehiro Y, et al. Inflammatory myoblastic tumor of the uterus and interleukin-6. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:890–1. 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00208-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gómez-Román JJ, Ocejo-Vinyals G, Sánchez-Velasco P, et al. Presence of human herpesvirus-8 DNA sequences and overexpression of human IL-6 and cyclin D1 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). Lab Invest 2000;80:1121–6. 10.1038/labinvest.3780118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the colon causing intussusception: a case report and literature review. WJG 2015;21:704–10. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright WF, Auwaerter PG. Fever and fever of unknown origin: review, recent advances, and Lingering dogma. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7:ofaa132. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Saito T, et al. P53 mutation and MDM2 amplification in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours. Histopathology 2003;42:431–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meis-Kindblom JM, Kjellström C, Kindblom LG. Inflammatory fibrosarcoma: update, reappraisal, and perspective on its place in the spectrum of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:133–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arber DA, Kamel OW, van de Rijn M, et al. Frequent presence of the Epstein-Barr virus in inflammatory pseudotumor. Hum Pathol 1995;26:1093–8. 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90271-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis JT, Gaffney RL, Casey MB, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen associated with a clonal Epstein-Barr virus genome. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol 2003;120:56–61. 10.1309/BUWN-MG5R-V4D0-9YYH [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coffin CM, Patel A, Perkins S, et al. Alk1 and p80 expression and chromosomal rearrangements involving 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Mod Pathol 2001;14:569–76. 10.1038/modpathol.3880352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin CA, Hawkins AL, Dvorak C, et al. Recurrent involvement of 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Cancer Res 1999;59:2776–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medeiros LJ, Elenitoba-Johnson KSJ. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;127:707–22. 10.1309/R2Q9CCUVTLRYCF3H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trinei M, Lanfrancone L, Campo E, et al. A new variant anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-fusion protein (ATIC-ALK) in a case of ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Cancer Res 2000;60:793–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Touriol C, Greenland C, Lamant L, et al. Further demonstration of the diversity of chromosomal changes involving 2p23 in ALK-positive lymphoma: 2 cases expressing ALK kinase fused to CLTCL (clathrin chain polypeptide-like). Blood 2000;95:3204–7. 10.1182/blood.V95.10.3204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lamant L, Dastugue N, Pulford K, et al. A new fusion gene TPM3-ALK in anaplastic large cell lymphoma created by a (1;2)(q25;p23) translocation. Blood 1999;93:3088–95. 10.1182/blood.V93.9.3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawrence B, Perez-Atayde A, Hibbard MK, et al. Tpm3-Alk and TPM4-ALK oncogenes in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am J Pathol 2000;157:377–84. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64550-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dishop MK, Warner BW, Dehner LP, et al. Successful treatment of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with malignant transformation by surgical resection and chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2003;25:153–8. 10.1097/00043426-200302000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagenstad CT, Kilpatrick SE, Pettenati MJ, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with bone marrow involvement. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:865–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butrynski JE, D'Adamo DR, Hornick JL, et al. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coffin CM, Humphrey PA, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinical and pathological survey. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanders BM, West KW, Gingalewski C, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the alimentary tract: clinical and surgical experience. J Pediatr Surg 2001;36:169–73. 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hussong JW, Brown M, Perkins SL, et al. Comparison of DNA ploidy, histologic, and immunohistochemical findings with clinical outcome in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Mod Pathol 1999;12:279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CDM. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:509–20. 10.1097/01.pas.0000213393.57322.c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]