Abstract

Background

Rice is a typical monocotyledonous plant and an important cereal crop. The structural units of rice flowers are spikelets and florets, and floral organ development and spike germination affect rice reproduction and yield.

Results

In this study, we identified a novel long sterile lemma (lsl2) mutant from an EMS population. First, we mapped the lsl2 gene between the markers Indel7–22 and Indel7–27, which encompasses a 25-kb region. The rice genome annotation indicated the presence of four candidate genes in this region. Through gene prediction and cDNA sequencing, we confirmed that the target gene in the lsl2 mutant is allelic to LONG STERILE LEMMA1 (G1)/ELONGATED EMPTY GLUME (ELE), hereafter referred to as lsl2. Further analysis of the lsl2 and LSL2 proteins showed a one-amino-acid change, namely, the mutation of serine (Ser) 79 to proline (Pro) in lsl2 compared with LSL2, and this mutation might change the function of the protein. Knockout experiments showed that the lsl2 gene is responsible for the long sterile lemma phenotype. The lsl2 gene might reduce the damage induced by spike germination by decreasing the seed germination rate, but other agronomic traits of rice were not changed in the lsl2 mutant. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the lsl2 gene will have specific application prospects in future rice breeding.

Conclusions

The lsl2 gene is responsible for the long sterile lemma phenotype and might reduce the damage induced by spike germination by decreasing the seed germination rate.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-020-02776-8.

Keywords: Rice (Oryza sativa L.), long sterile lemma mutant, Molecular marker, Gene cloning, Application prospect, Spike germination

Background

The flower forms of angiosperms are diverse, and flower morphology is the result of interactions among an established genetic programme, physical forces, and external forces induced by the pollination system [1]. Identifying floral organs and controlling the fate of meristems are essential for establishing this diversity. In eudicots, flowers are generally composed (from the outer to inner whorls) of sepals (whorls), petals (whorls), stamens (whorls), and pistils (whorls). Based on molecular and genetic analyses of several eudicot species, including Arabidopsis thaliana, snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), and petunia (Petunia hybrida), an ABC model that determines the characteristics of each organ and controls floral meristem determinacy based on the combination of A/B/C/D gene groups has been proposed [2–7]. According to the model, three homologous genes control the formation of flower organs. A-function genes independently specify sepal formation; the combination of A- and B-function genes determines petal identity; B- and C-function genes jointly regulate stamen development; and only the C-function gene specifies the innermost carpels. This genetic model applies to not only eudicots but also monocots, including some grass species such as rice (Oryza sativa L.) and maize (Zea mays) [8–12].

Rice is a typical monocotyledonous plant and an important cereal crop, and spikelets and florets are the structural units of rice flowers. The spikelet is the main unit of the rice inflorescence and contains a fertile floret and a pair of sterile lemmas (also known as “a sterile lemma”) [13], and the floret consists of a lemma, two lodicules (equivalent to petals), six stamens, and a pistil [14, 15].

A previous study showed that Sepallata (SEP) subfamily members and the LOFSEP subgroup of MADS-box genes play an important role in the development of rice flowers. During flower development, two SEP3 homologues and OsMADS7/8 are expressed in the inner three whorls and have redundant functions [16]. In addition to OsMADS7 and OsMADS8, LEAFY HULL STERILE1 (OsLHS1), OsMADS5 and OsMADS34/PAP2 reportedly function in flower development [17]. Some early studies found that OsMADS34/PAP2 regulates the identity of the spikelet meristem as well as ovule and sterile lemma development. In Osmads34/pap2 mutants, sterile lemmas are elongated to form leaf-like or lemma-like organs [17–19]. The results from evolution and sequence analyses of OsMADS34/PAP2 support the hypothesis that the sterile lemmas of rice originate from the degenerated floret lemma, which is named the rudimentary lemma [19]. LONG STERILE LEMMA1 (G1)/ELONGATED EMPTY GLUME (ELE) encodes a DUF640-containing protein that determines the identity of the sterile lemmas. The mutation of G1/ELE induces sterile lemmas to become lemma-like organs [20, 21]. Interestingly, natural mutations in the sterile lemmas cause similar homeotic conversions in the genome of allotetraploid Oryza grandiglumis, which suggests that sterile lemmas might constitute a series of lemma homologues modified by G1/ELE [20].

Although the molecular mechanisms that control the development of reproductive organs in rice are well known, the role of the long sterile lemma and whether it affects the agronomic character of rice remain unclear. In this study, long sterile lemma 2 (lsl2), a new strong mutant allele of G1, was identified in the Zhonghua11 (ZH11) background. We mapped lsl2, analysed the 3-D structure of the LSL2 protein, and found that the lsl2 protein harbours a one-amino-acid change, namely, the mutation of serine (Ser) 79 to proline (Pro), and this change is likely to alter the structure of the LSL2 protein. We also performed molecular cloning of lsl2 and analysed the agronomic characteristics of the lsl2 mutant. Together, the results indicate that lsl2 has specific value in rice crossbreeding.

Methods

Plant materials

Indica rice CO39 and japonica ZH11 were provided by the Plant Immunity Center at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University and were preserved at the Rice Research Institute at Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences (China). The long sterile lemma mutant in the ZH11 background was screened from the M2 population treated with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) and named long sterile lemma 2 (lsl2). In 2016 and 2017, about 800 individual plants of M1 population and 6000 individual plants of M2 population were planted in the field of Fuzhou Experimental Station of Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

In the summer of 2018, the lsl2 mutant was hybridized with the rice cultivars CO39 and ZH11 as the pollen donors. The F1 seeds were planted at Sanya (18.14 northern latitude, 109.31 east longitude) Experimental Station in Hainan Province in the spring, and F2 seeds were harvested. The F2 seeds lsl2 and ZH11 were sown at Fuzhou (26.08 northern latitude, 119.28 east longitude) Experimental Station in Fujian Province in the summer of 2019. The plant height, panicle number per plant, flag leaf length and width, spikelet number per panicle, and seed setting rate were measured at maturity. The segregation ratios of the mutant versus the wild-type plants were examined after maturity.

All the plants were planted in accordance with standard commercial procedures. The spacing between rows was 13.3 cm and 26.4 cm, and the field management of these plants generally followed normal agricultural practices.

Construction of the mapping population

The lsl2 mutant (japonica) was hybridized with CO39 (indica) to produce a mapping population. The F2 population was constructed through self-crossing of the F1 population, and 1084 mutant-phenotype plants in the F2 population were selected for fine mapping.

Microsatellite analysis

Simple sequence repeat (SSR) primers were obtained from the published rice database (http://www.Gramene.org/microsat/ssr.htm1). Indel markers were designed by manually comparing the genome sequences between japonica (cv. Nipponbare) [22] and indica (cv. 93–11) [23]. First, the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone sequences of japonica and indica were compared, and Primer premier 5.0 was then used to design primers for polymorphic regions between the two rice subspecies, which were used for gene localization.

PCR (polymerase chain reaction) amplification and marker detection

Plant DNA was extracted from frozen leaves of rice plants using the CTAB method [24], with minor modifications. For PCR amplification, every 20-μL reaction mixture contained 30 ng of DNA, 0.4 μM of each primer, and 2× Es Tag MasterMix (Dye). The amplification procedure was performed using the following program: 2 min at 94 °C, 33 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C, and a final extension of 2 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were electrophoresed in 3% agarose gels with ethidium bromide staining [25].

Bulked segregant analysis

Markers associated with target genes were identified by bulk segregant analysis (BSA). DNA from the leaves of 15 randomly selected mutant plants of the F2 population was used to construct a mutant DNA library. Linkage was detected based on the distribution of SSR markers in the rice genome through an analysis of DNA extracted from the lsl2 mutant and CO39 (used as a control). The bands of markers linked to the mutant genes were the same as those found with the lsl2 mutant.

Molecular mapping of the lsl2 gene

The band types of the mutants (lsl2 lsl2) and wild-type ZH11 (LSL2 LSL2) were denoted 1 and 3, respectively, and the heterozygote plants (lsl2 LSL2) were denoted 2. MAPMAKER Version 3.0 software was used for linkage analysis between the lsl2 locus and the SSR markers [26], and MapDraw V2.1 software was used for estimating the genetic distance [27]. The linkage map obtained in this study was almost equal to that reported previously [28].

First, 326 SSR markers were selected from the rice molecular map for analysis of the polymorphism between lsl2 and CO39 [29]. Among these markers, 205 pairs showed polymorphism, and based on these 205 markers, 15 mutant strains and 15 normal strains were selected from the F2 population for linkage analysis of the lsl2 locus. Second, to delineate the gene to a smaller region, we identified 1084 mutants from the F2 population of lsl2 × CO39, and indel markers from the open rice genome sequences were designed to predict the likelihood of polymorphisms between lsl2 and CO39 by comparing sequences from Nipponbare (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/) and the indica cultivar 93–11 (http://rice.genomics.org.cn/).

Physical map construction

Bioinformatics analysis was performed using Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and P1-derived artificial chromosome (PAC) clones of cv. Nipponbare released by the International Rice Genome Sequencing project (IRGSP, http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/IRGSP/index.html) to construct a physical map of the target gene. The clones were anchored to the target gene binding markers, and sequence alignment was performed by pairwise BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/bl2seq/b12.html).

Bioinformatics correlation analysis

Candidate genes were predicted based on existing sequence annotation database (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/; http://www.tigr.org/). The DNA and amino acid sequences of lsl2 and LSL2 were completely compared using Clustal X version 1.81. The 3-D structures of the lsl2 and LSL2 proteins were predicted and analysed (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/). A haplotype analysis of lsl2 and LSL2 was also performed (http://www.rmbreeding.cn/Genotype/haplotype).

Targeted mutagenesis of LSL2 in rice with CRISPR/Cas9

The LSL2 gene in ZH11 was targeted with one gRNA spacer that spanned 106 bp of the first exon of the gene. gRNA spacer sequences with high specificity (Supplementary Table 1) were designed using the CRISPR-plant database and website [30], and the genome-editing mutations of the target gene in the regenerated plants were evaluated. The chromosomal deletions and insertions were detected by PCR using primers located in gene target sites. The PCR products were selected from the transgenic CRISPR-edited lines for sequencing to identify specific mutations. Double peaks were resolved using the degenerate sequence decoding method [31]. The primers used in the CRISPR/Cas9 study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA extraction and expression status of LSL2 by RT-qPCR (quantitative reverse transcription PCR)

RNA extraction was performed using kits (Magen, IF210200) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Total RNA quality detection was performed with a Nanodrop for determining the RNA concentration; nondenaturing agarose electrophoresis for determining RNA integrity.

To verify the expression status of LSL2, empty glumes and lemma/palea were selected for qPCR. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription, Primer5 software was used to design QPCR primers, and the QPCR primer specificity was evaluated based on NCBI database (qPCR-F -5’CCGGGACTGGCAGACCTTCAC-3′, qPCR-R-5’GTCGCATCGCCGTCGTTCA3’). The ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 of constitutively expressed rice gene was normalized as an internal reference gene [32]. Three technical repeats were performed on each of the three biological repeats.

Measurement of the germination rates

Each rice material was incubated in a plant-light incubator for 24 h; 100 seeds of each material were germinated, and this process was repeated four times for each material. The germination test was conducted according to the standard germination test method. The germination bed consisted of paper, and the test was performed at 25 °C. The number of germinated seeds was recorded after 2 days, and the germination rate was continuously recorded until the 7th day. The moisture and temperature conditions were maintained.

Results

Main agronomic characteristics of lsl2

To elucidate the genes that regulate flower development in rice, we screened for a floret mutant phenotype among an EMS-mutagenized population and identified a long sterile lemma 2 (lsl2) mutant in the ZH11 background. Phenotypic comparisons between the lsl2 mutant and wild-type ZH11 plants are presented in Table 1. The results showed no significant differences in the major agronomic traits, including the plant height, panicle length, number of effective panicles, spikelets per panicle, seed-setting rate, 1000-grain weight, grain length and grain width.

Table 1.

Comparison of the main agronomic traits between ZH11 and lsl2

| Traits | ZH11 | lsl2 |

|---|---|---|

| Plant height (cm) | 77.62 ± 1.86 | 78.12 ± 1.82 |

| Panicle length (cm) | 25.22 ± 1.22 | 25.46 ± 1.20 |

| Number of effective panicles | 8.64 ± 1.04 | 8.84 ± 1.08 |

| Spikelets per panicle | 128.46 ± 4.26 | 132.36 ± 3.84 |

| Seed-setting rate (%) | 96.52 ± 0.16 | 97.38 ± 0.20 |

| 1000-grain weight (g) | 25.02 | 25.44 |

| Grain length (mm) | 8.57 ± 0.12 | 8.65 ± 0.13 |

| Grain width (mm) | 2.49 ± 0.08 | 2.52 ± 0.04 |

| Brown rice length (mm) | 5.72 ± 0.10 | 5.68 ± 0.08 |

| Brown rice width (mm) | 2.12 ± 0.04 | 2.14 ± 0.03 |

* P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 for the difference between ZH11 and lsl2. The data were derived from the trial performed at Fuzhou Experimental Station in October 2019

Phenotypic observations and analysis of the lsl2 mutant

At the vegetative stage, the phenotypes of the ZH11 and lsl2 plants were indistinguishable, but their spikelets displayed different phenotypes from the boot stage to the mature stage (Table 1 and Fig. 1a, b). The sterile lemma of the ls12 mutants was markedly longer than that of ZH11, although other components of the spikelet were the same (Fig. 1a, b). Interestingly, no significant difference in the grain size or brown rice size was found between lsl2 and ZH11 after maturation (Table 1 and Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypes of ZH11 and the ls2 mutant. a: grain phenotypes of ZH11; b: grain phenotypes of the ls2 mutant; c: brown rice phenotypes of ZH11; d: brown rice phenotypes of the ls2 mutant. The lsl2 mutant has a markedly longer sterile lemma compared with ZH11, and no significant difference in the grain size or shape were found between the lsl2 mutant and ZH11

We compared the germination rates of the lsl2 and ZH11 seeds. On the second day, the wild-type ZH11 plants started sprouting (69.3%), but the lsl2 mutant had barely begun to germinate (2.3%) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Compared with the wild-type plants, the lsl2 mutants showed clearly reduced germination rates from the second day to the fourth day (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the germination rate between lsl2 mutant and ZH11 seeds. ZH11 showed a higher germination rate than the lsl2 mutant starting on the second day

Table 2.

Comparison of the germination rates between ZH11 and lsl2

| Number of days | 1d | 2d** | 3d** | 4d * | 5d | 6d | 7d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of the material | |||||||

| Germination rate of ZH11 (%) | 0 | 69.3 | 94.8 | 95.3 | 95.8 | 96.8 | 96.8 |

| Germination rate of lsl2 (%) | 0 | 2.3 | 63.5 | 82.5 | 94.6 | 95.6 | 95.6 |

* P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 for the difference between ZH11 and lsl2

Genetic analysis of the lsl2 mutant

To determine whether the lsl2 mutant is caused by a single gene, we then crossed the lsl2 mutant with ZH11. The F1 generation showed normal phenotypes, and the F2 population exhibited Mendelian segregation (Table 3). Indeed, the segregation between the wild-type and mutant plants corresponded to a 3:1 segregation ratio in the two F2 populations (χ2 = 0.124 ~ 0.462, P > 0.5), which indicated that the lsl2 mutant phenotype is controlled by a single recessive gene.

Table 3.

Segregations of the F2 population produced by crossing the lsl2 mutant

| Crosses | F1 phenotype | F2 population | χ2 (3:1) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type plants | Mutant plants | Total plants | ||||

| lsl2/ZH11 | Normal type | 180 | 57 | 237 | 0.462a | 0.5–0.75 |

| ZH11/lsl2 | Normal type | 198 | 64 | 262 | 0.124a | > 0.9 |

a Denotes the segregation ratio of normal to mutant plants complying with 3:1 at the 0.05 significance level

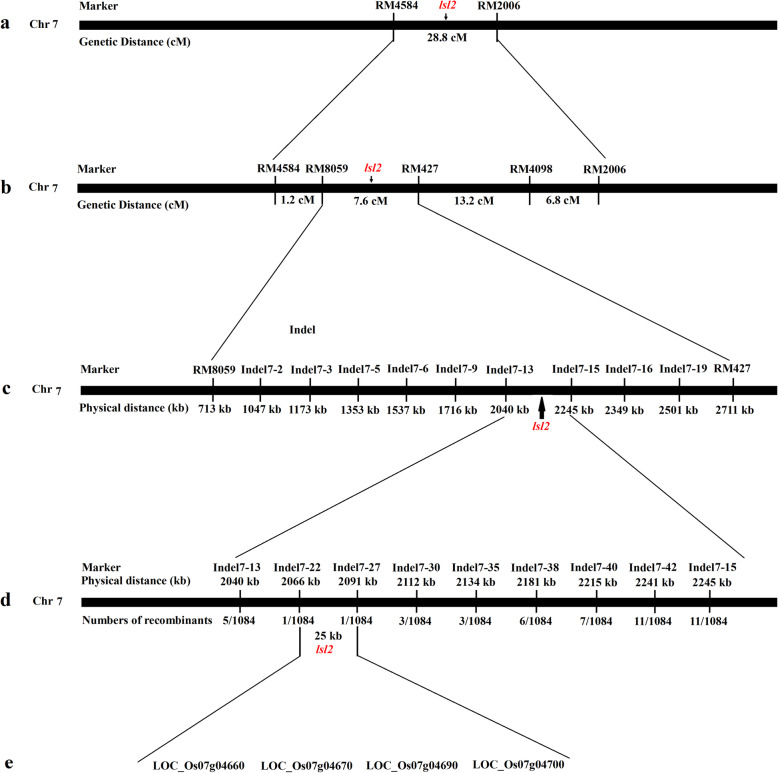

Initial localization of the lsl2 gene

To determine which gene mutation causes the lsl2 phenotype, we then mapped the lsl2 gene. Two SSR markers located on rice chromosome 7, RM4584 and RM2006, were found to be associated with mutant traits in 193 F2 individuals. Based on the recombination frequency, the genetic distance between RM4584 and RM2006 was calculated to equal 28.8 cM. Therefore, lsl2 is located in a 28.8-cM region on chromosome 7 flanked by the SSR markers RM4584 and RM2006 (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

The localization of the lsl2 gene. a: The lsl2 gene was primarily mapped the region between markers RM4584 and RM2006 on chromosome 7. b: The lsl2 gene was further mapped to the region between SSR markers RM8059 and RM427. c: The lsl2 gene was fine mapped to the region between InDel markers Indel7–13 and Indel7–15. d: The lsl2 gene was ultimately localized to a 25.0-kb region between InDel markers Indel7–22 and Indel7–27, and the physical distance and numbers of recombinants were shown below the corresponding markers. e: In the 25.0-kb region, 4 putative genes were annotated

Fine mapping of the lsl2 gene

To delineate the gene to a smaller region, an accurate map between RM4584 and RM2006 was constructed using published markers (Table 4). Through genetic linkage analysis, the lsl2 gene was mapped between the molecular markers RM8059 and RM427, with a distance of 7.6 cM (Fig. 3b). For further mapping, all recombinant genes were genotyped using nine polymorphic markers (Table 4). The results showed that the lsl2 gene is located between the molecular markers Indel7–13 and Indel7–15, with a physical distance of 205 kb (Fig. 3c and Table 4). For the fine mapping of the lsl2 gene, seven polymorphic indel markers for recombinant screening (Table 4) detected one, one, three, three, six, seven and 11 recombinant plants (Fig. 3d). Thus, we precisely localized the lsl2 gene between the molecular markers Indel7–22 and Indel7–27, with a physical distance of 25.0 kb.

Table 4.

Indel and SSR molecular markers used for fine mapping of the lsl2 gene

| Marker | Sequence of the forward primer | Sequence of the reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| RM8059 | GGAAAGACCAGTTTAGAGCAATGG | AGCTAGATCCCTTGTTTCACACG |

| RM427 | TCACTAGCTCTGCCCTGACC | TGATGAGAGTTGGTTGCGAG |

| RM4098 | CGTTTGGATGAAGAAGAAGA | AGTGTTCGTTTCGGATTAGA |

| Indel7–2 | CAGATATGATGTTCTTGCCCTTGC | GCTTGCCAGATCACCTACCTACC |

| Indel7–3 | CGGAGCTGTTGCCGTTCTGC | CGATGTGCCATGTCAGGATGACC |

| Indel7–5 | CCTACCGCGTCATTCACATGC | GACAAGATCGACAGCCGCTACG |

| Indel7–6 | TCACTCACACACTGACTGACACG | TCTCGTCGGAGAAGAAGATGAGC |

| Indel7–9 | CACTATGGATCTTGGTGGTCAAGG | TGCTATCTGCTACCGTCAACACG |

| Indel7–13 | GTAGGACATGAAGGCGGCTAGG | ATCTCCTGCCACTGCACACC |

| Indel7–15 | CGTCCATATCAAACCTCTTCTTCC | GTAACATTCCCTCCCGAACTCC |

| Indel7–16 | GGTGCAGACTACCTAAATATGACG | GTAAACCGATGGCTTAGAGTCC |

| Indel7–19 | AACGGGAGATCACAGGAATTTGC | GTGTTCGACTCGTCTCCATTTCG |

| Indel7–22 | ACAGTGAAAGCCACTACCAT | CTTGACTGGGTGTCCATATT |

| Indel7–27 | TAGGTGCAACTTCTTGAAGTG | GATCCCCTGTTCATTTGTAATT |

| Indel7–30 | AGGGGCGCACAGCGGGGAGGGTC | TCAATCCACGGAATCCACGAC |

| Indel7–35 | GATTTCAGAAGATGTTTGGG | GGTTTCCCAGTTTCTGTCTT |

| Indel7–38 | TGATTTTATCCTCGTCTTCC | AACATGCGCATATGTAACTG |

| Indel7–40 | TCTCTTCTCTCTTGCTTCTC | ATGTCAATTTGATGGGATGT |

| Indel7–42 | TGGAAAAGAACTTCAATGCT | TTGAATCACCACAATTTAGC |

Candidate genes in the 25.0-kb region

Four candidate genes (LOC_Os07g04660, LOC_Os07g04670, LOC_Os07g04690, and LOC_Os07g04700) were annotated in this 25.0-kb region (Fig. 3e). According to the available annotation database, these four genes all have a corresponding full-length cDNA. LOC_Os07g04660 encodes white-brown complex homologue protein 16, and LOC_Os07g04670, LOC_Os07g04690 and LOC_Os07g04700 encode a DUF640 domain-containing protein, UDP-arabinose 4-epimerase 1, and an MYB family transcription factor, respectively.

Sequence analyses of the lsl2 gene

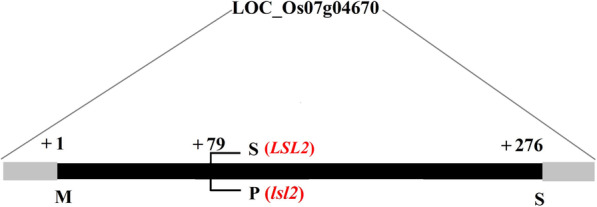

To analyse which gene causes the mutant phenotype, we sequenced the above-mentioned four genes in ZH11 and lsl2 and found only a single 1-bp change (T to C) in LOC_Os07g04670 between the wild-type ZH11 and lsl2 mutant plants. No other differences in the sequences of the three other genes were observed. Thus, we speculated that the LOC_Os07g04670 locus corresponds to lsl2. Interestingly, the G1/ELE gene, which encodes a DUF640 domain-containing protein, is present in this locus [20]. Based on the results from phenotypic similarity and localization analyses, we hypothesized that the long sterile lemma phenotype of lsl2 might be caused by functional changes in the product of the LOC_Os07g04670 locus. These results suggest that the lsl2 gene might be allelic with G1/ELE.

The analysis of the open reading fragment (ORF) of the LSL2 gene (LOC_Os07g04670) showed one exon and no intron. lsl2 was a 1-bp mutant that resulted in the exchange of a serine (Ser) for a proline (Pro) (Fig. 4). Ser is a polar amino acid, whereas Pro is nonpolar. Thus, this mutation might alter the function of a protein.

Fig. 4.

Structural comparison between the LSL2 and lsl2 proteins. Only one amino acid substitution (S79P) was found between LSL2 and lsl2

The lsl2 gene is responsible for the long sterile lemma phenotype

To confirm that the mutation phenotype can be attributed to lsl2, we examined whether the knockout of LSL2 in the cultivar ZH11 would lead to the long sterile lemma phenotype. One sequence-specific guide RNA (sgRNA) was designed to knock out the LSL2 gene using the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system. A total of three plants from three independent events were obtained and confirmed by sequencing to carry insertions and deletions in the target sites (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mutation site of three targeted mutant lines

| Line | Target type | Mutation site |

|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | gRNAs | ACTGGCAGACCTTCACGCAGTTACCTCGCCGCGCACCGCCCGC (1-bp insertion) |

| Line 2 | gRNAs | ACTGGCAGACCTTCACGCAGT--CTCGCCGCGCACCGCCCGC (2-bp deletion) |

| Line 3 | gRNAs | ACTGGCAGACCTTCACGCAGT-CCTCGCCGCGCACCGCCCGC (1-bp deletion) |

We then investigated the panicle characteristics of these three homozygous lines after maturity and found that all three exhibited a long sterile lemma phenotype (Fig. 5), which indicated that the knockout of LSL2 in ZH11 leads to the long sterile lemma mutation phenotype.

Fig. 5.

LSL2-knockout mutants show a long sterile lemma phenotype. The three knockout lines generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology exhibit a long sterile lemma phenotype

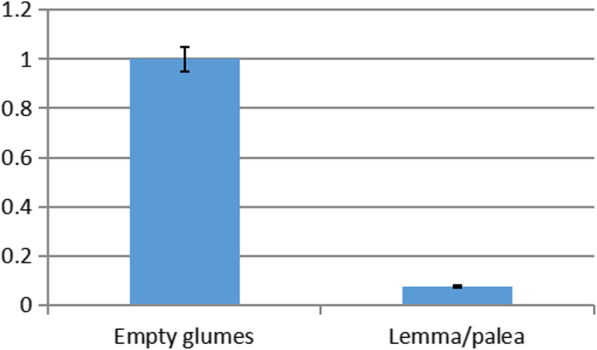

QPCR confirms expression status of LSL2

To verify the expression status of LSL2, empty glumes and lemma/palea were selected for qPCR. The results showed that the LSL2 was expressed significantly differently in empty glumes and lemma/palea, and the expression level in empty glumes was significantly higher than that in lemma/palea (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The expression status of LSL2 between empty glumes and lemma/palea. The expression level of LSL2 in empty glumes was significantly higher than that in lemma/palea

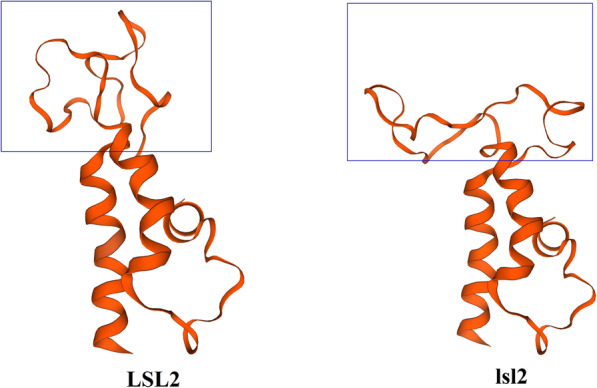

Analyses of 3-D structures between the LSL2 protein and the lsl2 protein

Further simulations of the 3-D structures of the proteins revealed changes between the lsl2 and LSL2 proteins (Fig. 7). Moreover, the change in residue 79 of LSL2 from Ser to Pro induced a significant change in the protein structure (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

3-D structures of the LSL2 protein and the lsl2 protein. There are significant structural changes based on the Swiss-Model, and the 79th residue of the LSL2 protein is changed from a serine (S) to proline (P), which significantly affects the structure. The blue box shows where the 79th amino acid is changed

Haplotype analysis of the LSL2 gene

To further investigate the genetic and evolutionary characteristics of the LSL2 gene, we performed SNP (Single nucleotide polymorphisms) calling and haplotype analysis of the 3000 sequenced rice genomes available in the CNCGB and CAAS databases [33] and found 492 haplotypes for the LSL2 gene, including 49 haplotypes among more than 15 rice resource materials (Supplementary Table 2). However, no haplotype or SNP was found for the lsl2 mutant in the 3000 sequenced rice genomes.

Discussion

Mechanism controlling the development of empty glumes and lemmas

The molecular mechanism that determines the development of the lemma differs from that involved in the development of the empty glume [13]. It is reported that two genes, G1/ELE and OsMADS34/PAP2, determine the identity of empty glumes [13]. Studies have shown that the G1/ELE gene is key for maintaining the identities of empty glumes [20]. Similarly, Lin et al. ‘s research shows that the OsMADS34/PAP2 gene plays a key role in empty glume development [19]. Through an analysis of Osmads34/pap2 mutant plants, Lin et al. proposes that the empty glume originates from the lemma and named it the basic lemma [19]. OsMADS1 specifies the identities of the lemma and palea and distinguishes the empty glume from the lemma/palea [34, 35].

However, there are several controversial explanations for regarding the identities of empty glumes, including true glumes and lemmas. For example, studies have shown that the empty glume was the remnant of two lower reduced florets [20], and in the same way, Lin et al. hypothesized that empty glumes were derived from the lemma and named these empty lemmas with degraded lemmas [19]. Most likely, as more and more genes controlling lemma development are cloned and identified, and their expression in empty glume is further analyzed, these findings will be provide clues for determining the identities of empty glumes.

In this study, we knocked out the LSL2 gene using the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system, and three independent lines were obtained for the target sites: Line 1 carries a 1-bp insertion, Line 2 harbours a 2-bp deletion, and Line 3 carries a 1-bp deletion. Further analysis of the panicle characteristics showed that all three lines exhibited a long sterile lemma phenotype (Fig. 5 and Table 5), and this phenotype was the same as that of the lsl2 mutant. Therefore, the lsl2 gene was found to be responsible for the long sterile lemma phenotype.

Further research and molecular evidence of lemma development will provide clues for determining the identity of empty glumes. Further investigations are also necessary to reveal the key genes that play a role in the lemma-based identification of glumes.

Genetic and evolutionary analyses of the LSL2 gene

A haplotype analysis of the 3000 sequenced rice genomes showed 492 haplotypes for the LSL2 gene (Supplementary Table 2). However, no haplotype or SNP for the lsl2 mutant, which contains a T-to-C mutation, was found in the 3000 sequenced rice genomes. We speculate that a mutation at this site would be strongly selected against in natural selection and would only be the result of manual selection. For example, the phenotypes of lsl2 might be inconsistent with the expectations of breeders; therefore, this mutation was gradually eliminated by manual selection.

Because simulations of the 3-D structures of LSL2 and lsl2 showed that the T-to-C amino acid change alters the protein structure (Fig. 7), we speculate that this change might affect the specific function of LSL2, such as its binding activity to its target protein.

Analysis of the application prospect of the LSL2 gene

Although the lsl2 mutation did not affect major agronomic traits, whether it affects the internal characteristics of rice remains unclear. The comparison of the germination rates of lsl2 and ZH11 seeds revealed that the lsl2 mutant exhibited obviously reduced germination rates from the second day to the fourth day (Table 2). We propose that the most likely reason for this difference is that the longer sterile lemma of lsl2 might inhibit the growth of embryos.

Spike germination in rice is closely related to the seed germination rate. In the production of hybrid rice worldwide, spike germination is a prominent issue that affects both the yield and processing quality of rice, and these effects cause economic losses to different degrees [36]. In this study, we found that the lsl2 mutation reduced the damage induced by spike germination by decreasing the seed germination rate. Interestingly, other agronomic traits of rice were not affected in the lsl2 mutant (Table 1). Therefore, the lsl2 gene has specific application prospects in rice breeding. First, breeders can develop excellent conventional rice varieties using lsl2. Second, the lsl2 gene is controlled by a single recessive gene (Table 3); thus, to breed a new hybrid rice variety, breeders can transfer this gene into both restorer and sterile lines using molecular marker-assisted selection.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified a novel long sterile lemma (lsl2) mutant from an EMS population and found that the lsl2 gene is responsible for the long sterile lemma phenotype and that a one-amino-acid change, the mutation of serine (Ser) 79 to proline (Pro) in the lsl2 protein compared with the LSL2 protein, might change the function of the LSL2 protein. The results of this study indicate that the lsl2 mutant might reduce the damage caused by spike germination by decreasing the seed germination rate.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Primer sequences used for the synthesis of gRNA spacers and the genotyping of CRISPR-edited mutants.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 2. Haplotype analysis of LSL2. (DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SSR

Simple sequence repeat

- Indel

Insertion/deletion

- ZH11

Zhonghua11

- BAC

Bacterial artificial chromosome

- PAC

P1-derived artificial chromosome

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- EMS

Ethyl methanesulfonate

- lsl2

long sterile lemma 2

- RT-qPCR

quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Authors’ contributions

DY planned and carried out the experiments and data collection and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. NH, XZ, YZ, ZX, CC and FH were involved in conducting the experiments, data collection and analyses. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of Fujian Province (No. 2020R11010016–3), Youth Technology Innovation Team of Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences (No. STIT2017–3-3) and the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2019 J01011040). These three funders provided financial support in our study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The genome sequence of the LSL2 can be found in the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and the number of GenBank is AB512480.1.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.De Craene LR. Understanding the role of floral development in the evolution of angiosperm flowers: clarifications from a historical and physico-dynamic perspective. J Plant Res. 2018;131:367–393. doi: 10.1007/s10265-018-1021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coen ES, Meyerowitz EM. The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature. 1991;353:31–37. doi: 10.1038/353031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theissen G, Saedler H. Plant biology: floral quartets. Nature. 2001;409:469–471. doi: 10.1038/35054172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irish V. The ABC model of floral development. Curr Biol. 2017;27:R887–R890. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali Z, Raza Q, Atif RM, Aslam U, Ajmal M, Chung G. Genetic and molecular control of floral organ identity in cereals. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(11):2743. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang HM, Tong CG, Jang S. Current progress in orchid flowering/flower development research. Plant Signal Behav. 2017;12(5):e1322245. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2017.1322245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson B, Wellmer F. Molecular regulation of flower development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2019;131:185–210. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagasawa N, Miyoshi M, Sano Y, Satoh H, Hirano H, Sakai H, Nagato Y. SUPERWOMAN 1 and DROOPING LEAF genes control floral organ identity in rice. Development. 2003;130:705–718. doi: 10.1242/dev.00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi T, Lee DY, Miyao A, Hirochika H, An G, Hirano HY. Functional diversification of the two C-class MADS box genes OSMADS3 and OSMADS58 in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell. 2006;18:15–28. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreni L, Jacchia S, Fornara F, Fornari M, Ouwerkerk PB, An G, Colombo L, Kater MM. The D-lineage MADS-box gene OsMADS13 controls ovule identity in rice. Plant J. 2007;2:690–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu W, Tao JH, Chen MJ, Dreni L, Luo ZJ, Hu Y, Liang WQ, Zhang DB. Interactions between FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER4 and floral homeotic genes in regulating rice flower development. J Exp Bot. 2017;68:483–498. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu Y, Liang WQ, Yin CS, Yang XL, Ping BZ, Li AX, Jia R, Chen MJ, Luo ZJ, Cai Q, Zhao XX, Zhang DB, Yuan Z. Interactions of OsMADS1 with floral homeotic genes in rice flower development. Mol Plant. 2015;8(9):1366–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu MJ, Li HF, Su YL, Li WQ, Shi CH. G1/ELE functions in the development of fice lemmas in addition to determining identities of empty glumes. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1006. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida H, Nagato Y. Flower development in rice. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:4719–4730. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardo F, Yoshida H. Interpreting lemma and Palea homologies: a point of view from rice floral mutants. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:61. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui RF, Han JK, Zhao SZ, Su KM, Wu F, Du XQ, Xu QJ, Chong K, Theissen G, Meng Z. Functional conservation and diversification of class E floral homeotic genes in rice (Oryza sativa) Plant J. 2010;61:767–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi K, Maekawa M, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Kyozuka J. PANICLE PHYTOMER2 (PAP2), encoding a SEPALLATA subfamily MADS- box protein, positively controls spikelet meristem identity in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:47–57. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao XC, Liang WQ, Yin CS, Ji SM, Wang HM, Su X, Guo C, Kong HZ, Xue HW, Zhang DB. The SEPALLATA-like gene OsMADS34 is required for rice inflorescence and spikelet development. Plant Physiol. 2010;53:728–740. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin XL, Wu F, Du XQ, Shi XW, Liu Y, Liu SJ, Hu YX, Theißen G, Meng Z. The pleiotropic SEPALLATA-like gene OsMADS34 reveals that the ‘empty glumes’ of rice (Oryza sativa) spikelets are in fact rudimentary lemmas. New Phytol. 2014;202:689–702. doi: 10.1111/nph.12657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida A, Suzaki T, Tanaka W, Hirano HY. The homeotic gene long sterile lemma (G1) specifies sterile lemma identity in the rice spikelet. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:20103–20108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907896106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong LL, Qian Q, Zhu KM, Tang DX, Huang ZJ, Gao L, Li M, Gu MH, Cheng ZK. EL Erestrains empty glumes from developing into lemmas. J Genet Genomics. 2010;37:101–115. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan TH, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H, Hadley D, Hutchison D, Martin C, Katagiri F, Lange BM, Moughamer T, Xia Y, Budworth P, Zhong J, Miguel T, Paszkowski U, Zhang S, Colbert M, Sun WL, Chen L, Cooper B, Park S, Wood TC, Mao L, Quail P, Wing R, Dean R, Yu Y, Zharkikh A, Shen R, Sahasrabudhe S, Thomas A, Cannings R, Gutin A, Pruss D, Reid J, Tavtigian S, Mitchell J, Eldredge G, Scholl T, Miller RM, Bhatnagar S, Adey N, Rubano T, Tusneem N, Robinson R, Feldhaus J, Macalma T, Oliphant A, Briggs S. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L ssp Japonica) Science. 2002;96:920–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu J, Hu SN, Wang J, Wong GK S, Li SG, Liu B, Deng YJ, Dai L, Zhou Y, Zhang XQ, Cao M L, Liu J, Sun JD, Tang JB, Chen YJ, Huang XB, Lin W, Ye C, Tong W, Cong LJ, Geng JN, Han YJ, Li L, Li W, Hu GQ, Huang XG, Li WJ, Li J, Liu ZW, Li L, Liu JP, Q, QH, Liu JS, Li L, Li T, Wang XG, Lu H, Wu TT, Zhu M, Ni PX, Han H, Dong W, Ren XY, Feng XL, Cui P, Li XR, Wang H, Xu X, Zhai WX, Xu Z, Zhang J S, He SJ, Zhang JG, Xu JC, Zhang KL, Zheng XW, Dong JH, Zeng WY, Tao L, Ye J, Tan J, Ren XD, Chen XW, He J, Liu DF, Tian W, Tian CG, Xia HG, Bao QY, Li G, Gao H, Cao T, Wang J, Zhao WM, Li P, Chen W, Wang XD, Zhang Y, Hu J F, Wang J, Liu S, Yang J, Zhang G , Xiong YQ, Li ZJ, Mao L, Zhou CS, Zhu Z, Chen RS, Hao BL, Zheng WM, Chen SY, Guo W, Li GJ, Liu SQ, Tao M, Wang J, Zhu LH, Yuan LP Yang, HM. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L ssp Indica). Science. 2002;296:79–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panaud O, Chen X, Mccouch SR. Development of microsatellite and characterization of simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) in rice (Oryza sativa L) Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:597–607. doi: 10.1007/BF02172406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lander ES, Green P, Abrahamson J, Barlow A, Daly MJ, Lincoln SE, Newberg LA. Mapmaker: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics. 1987;1:174–181. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(87)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu HR, Meng JL. MapDraw: amicrosoft excelmacrofor drawing genetic linkage maps based on given genetic linkage data. Hereditas (Beijing) 2003;25:317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman ML, Chu SH, Choi MS, Qiao YL, Jiang WZ, Piao RH, Khanam S, Cho YI, Jeung JU, Jena KK, Koh HJ. Identification of QTLs for some agronomic traits in rice using an introgression line from Oryaza minuta. Mol Cell. 2007;24:16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mccouch SR, Teytelma L, Xu YB, Lobos KB, Clare K, Walton M, Fu BY, Maghirang R, Li ZK, Xing YZ, Zhang QF, Kono I, Yano M, Fjellstrom R, Declerck G, Schneider D, Cartinhour S, Ware D, Stein L. Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza setiva L) DNA Res. 2002;9:257–279. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.6.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie KB, Zhang JW, Yang YN. Genome-wide prediction of highly specific guide RNA spacers for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in model plants and major crops. Mol Plant. 2014;7:923–926. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma XL, Chen LT, Zhu QL, Chen YL, Liu YG. Rapid decoding of sequence-specific nuclease-induced heterozygous and biallelic mutations by direct sequencing of PCR. Products. Mol Plant. 2015;8:1285–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jain M, Nijhawan A, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP. Validation of housekeeping genes as internal control for studying gene expression in rice by quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2006;345:646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li ZK, Fu BY, Gao YM, Wang WS, Xu JL, Zhang F, Zhao XQ, Zheng TQ, Zhou YL, Zhang G, Tai SS, Xu JB, Ws H, Yang M, Niu YC, Wang M, Li YH, Bian LL, Han XL, Li J, Liu X, Wang B. The 3,000 rice genomes project. Gigascience. 2014;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad K, Parameswaran S, Vijayraghavan Usha. OsMADS1, a rice MADS-box factor, controls differentiation of specific cell types in the lemma and Palea and is an early-acting regulator of inner floral organs. Plant J 2005;43(6):915–928. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Wang L, Zeng XQ, Zhuang H, Shen YL, Chen H, Wang ZW, Long JC, Ling YH, He GH, Li YF. Ectopic expression of OsMADS1 caused dwarfism and spikelet alteration in rice. Plant Growth Regul. 2017;81(3):433–442. doi: 10.1007/s10725-016-0220-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, Tang H. Effects of exogenous ABA on panicle sprouting of F1 in hybrid rice seed production. Acta Agron Sin. 2000;26(1):59–64. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Primer sequences used for the synthesis of gRNA spacers and the genotyping of CRISPR-edited mutants.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 2. Haplotype analysis of LSL2. (DOCX 17 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The genome sequence of the LSL2 can be found in the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and the number of GenBank is AB512480.1.