Abstract

Although the survival rate of patients with cancer have increased due to the use of current chemotherapeutic agents, adverse effects of cancer therapy remain a concern. The reversal of drug resistance, reduction in harmful side effects and accelerated increase in efficiency have often been addressed in the development of combination therapeutics. Tazemetostat (EPZ-6438), a histone methyltransferase EZH2 selective inhibitor, was approved by the FDA for the treatment of advanced epithelioid sarcoma. However, the effect of tazemetostat on colorectal cancer (CRC) and 5-FU sensitivity remains unclear. In this study, the enhancement of tazemetostat on 5-FU sensitivity was examined in CRC cells. Our findings demonstrated that tazemetostat combined with 5-FU exhibits synergistic antitumor function in vitro and in vivo in CRC cells. In addition, tazemetostat promotes PUMA induction through the ROS/ER stress/CHOP axis. PUMA depletion attenuates the antitumor effect of the combination therapy. Therefore, tazemetostat may be a novel treatment to improve the sensitivity of tumors to 5-FU in CRC therapy. In conclusion, the combination of 5-FU and tazemetostat shows high therapeutic possibility with reduced unfavorable effects.

Subject terms: Chemotherapy, Colon cancer

Introduction

Statistically, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common disease in the world and is the cause of one quarter of recorded cancer deaths1,2. Despite the survival rate of CRC patients has improved, it is still significantly lower than the rates of patients with other cancers3. The chance of 5-year survival has been reported as being less than the tenth percentile for patients with metastatic CRC3. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are the usual courses of treatment for patients with CRC3,4. Generally, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and irinotecan are utilized for CRC chemotherapy, but they have poor efficiency, relatively high toxicity, and confer various negative effects5. Additionally, adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimens are sometimes not effective for patients with stage II and III or distant metastasis CRC6. Therefore, the solution is to develop a combination therapy that overcome the harmful side effects and act against drug resistance7. Thus, new agents are needed to increase the efficiency of chemotherapy and reduce the negative effects of treatment.

Cancer can be caused by changes in epigenetic status, and more than one-half of cancer patients carry mutated proteins associated with chromatin8. In order to develop new and effective cancer treatments, there is growing interest in the development of drugs that particularly target epigenetic modifier complexes9. A prominent target is EZH2 (enhancer of zeste 2), which usually has mutations and is involved in the gain of function or overexpression in several types of tumors10,11. During embryogenesis, lysine 27 on histone 3 (H3K27me3) methylation is catalyzed by EZH2 and is a modification at the epigenetic level that is important for repressing developmental genes12. EZH2 is the catalytic portion of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which also includes the embryonic ectoderm development (EED) and suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12)13,14. The enzymatic activity of PRC2 is compromised when even one of these three protein subunits is inactivated, which leads to the loss of the H3K27me3 mark15.

The p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA, also known as BBC3) belongs to the Bcl-2 BH3-only family and potently induces apoptosis16. The binding of PUMA to the Bcl-2 family members that are antiapoptotic, including Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, and MCL-1, releases Bax and Bak, permeabilizes the mitochondrial membrane, and ultimately activates the caspase signaling cascade17,18. The induction of PUMA is modulated by p53-dependent and p53-independent processes18. Owing to p53 abnormalities, PUMA can be dysregulated. For instance, dysfunctional p53-dependent PUMA regulation leads to the survival of tumor cells and resistance to therapeutics19. However, various transcription factors, including FoxO3a20, p6521, CHOP22, and p7323, have been indicated in the induction of PUMA independent of p53.

In the current study, we investigated whether EZH2 inhibition enhances the antitumor effect of 5-FU in CRC. At concentrations that were non-cytotoxic to the cells, efficient induction of cell death was observed by 5-FU administered with tazemetostat to CRC cells. Our findings indicated that tazemetostat enhanced 5-FU-induced apoptosis by inducing PUMA upregulation and mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. We also showed that reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, mediated by tazemetostat, enhanced 5-FU sensitivity. Collectively, the results indicate that tazemetostat can enhance the therapeutic effect of 5-FU through the upregulation of PUMA in CRC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human CRC cell lines HCT116, SW480, HT29, SW48, and DLD1 and normal colon cell lines FHC and CCD-18Co were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) with fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone; 10%), sodium bicarbonate (26 mmol/L), and L-glutamine (1 mmol/L) for the single-layered cell culture. PUMA- and CHOP-knockout (PUMA-KO and CHOP-KO) HCT116 and DLD1 cells were generated using the CRISPR-Cas 9 system as described in a previous study24. The sgRNA used in this paper are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

sgRNA sequence.

| sg Name | gRNA target sequence |

|---|---|

| PUMA | 5′-GTAGAGGGCCTGGCCCGCGA-3′ |

| CHOP | 5′-CCGAGCTCTGATTGACCGAA-3′ |

MTS

The cell proliferation assay was carried out using the MTS (Invitrogen) according to the instructions. Indicated cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and cultured for 24 h. Then the cells were treated with tazemetostat and cell proliferation was determined through MTS assay. The cell proliferation was expressed in terms of absorbance at 590 nm. Each experiment was replicated at least thrice, independently.

Colony formation

Colony formation assay was performed as described in a previous study25. In 6-well plates, 1 × 103 cells were incubated per well for the colony formation assay. The colonies that were visible were fixed after 14 days using formaldehyde (4%) and crystal violet stained.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described in previous studies26,27. The cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, and 1% Na deoxycholate at pH 7.4) with a cocktail of phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). The bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to estimate the concentration of protein. Proteins in equivalent amounts were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by blocking with TBS-T (containing 5% non-fat milk and 0.5% Tween-20) and incubation overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. Then, secondary antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were added for 1 h at room temperature, and the signals were detected with X-ray film. The primary antibodies used are as follows: EZH2 (ab191080, Abcam), SUZ12 (ab175187, Abcam), EED (ab4469, Abcam), H3K27me3 (ab192985, Abcam), cleaved caspase 3 (#9661, Cell Signaling Technology), cleaved caspase 9 (#9502, Cell Signaling Technology), PUMA (#12450, Cell Signaling Technology), BAK (#6947, Cell Signaling Technology), Mcl-1 (#94296, Cell Signaling Technology), Bcl-2 (#4223, Cell Signaling Technology), Bcl-xL (#2764, Cell Signaling Technology), Survivin (#2808, Cell Signaling Technology), Bim (#2819, Cell Signaling Technology), cytochrome c (ab133504, Abcam), COX IV (#4850, Cell Signaling Technology), CHOP (#2895, Cell Signaling Technology), eIF2α (#5324, Cell Signaling Technology), p-eIF2α (#9721, Cell Signaling Technology), p53 (sc-126, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FoxO3a (#2497, Cell Signaling Technology), p-FoxO3a (#9466, Cell Signaling Technology), p65 (#8242, Cell Signaling Technology), p-p65 (#3033, Cell Signaling Technology), p73 (#14620, Cell Signaling Technology), 4HNE (ab46545, Abcam), 3NT (ab61392, Abcam), and β-actin (A5441, Sigma).

Real-time PCR

The total RNA isolation was carried out with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). After the RNA isolation, the reverse transcription of RNA (1 μg) was performed via M-MLV RT (reverse transcriptase, Promega). Real-time PCR was analyzed using SYBR Green (Invitrogen) and CFX96 Touch sequence detection system (Bio-Rad, USA). β-Actin was used as the internal control. Equation, 2−ΔΔCT was used for the determination of relative gene expression. All reactions were evaluated in triplicates. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

PCR primers.

| PUMA | |

| Forward | 5′-ACGACCTCAACGCACAGTACG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCCATGATGAGATTGTACAGGA-3′ |

| β-Actin | |

| Forward | 5′-CGTGATGGTGGGCATGGGTC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ACGGCCAGAGGCGTACAGGG-3′ |

Small interfering RNA

The siRNAs for the negative control (sc-37007), EZH2 (sc-35312), and p53 (sc-44218) were procured from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. These siRNAs were transfected into cells with Lipofectamine RNAi Max reagents (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell apoptosis analysis using flow cytometry

Apoptosis was analyzed by an Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions28. Briefly, the cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min with Annexin V/PI reagent in the dark. Then, after terminating the staining reaction, the cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

ROS measurements

Dihydroethidium (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to measure ROS generation. The cells were incubated with DHE (dihydroethidium; 10 mmol/L) for 1 h. Furthermore, by using a flow cytometer, the intensity of the fluorescence was studied after the cells were washed with PBS.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were performed with HCT116 cells using a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described22. The Primers for ChIP are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

ChIP primers.

| Primers for amplification of the PUMA promoter | |

| #1 Forward | 5′-GCAGGAGTTTGAAACCAGCC-3′ |

| #1 Reverse | 5′-AGAAACTGACCACCCACACA-3′ |

| #2 Forward | 5′-GCGAGACTGTGGCCTTGTGT-3′ |

| #2 Reverse | 5′-GACAGTCGGACACACACACT-3′ |

| Primers for amplification of the CHOP promoter | |

| #1 Forward | 5′-AAGGCACTGAGCGTATCATG-3′ |

| #1 Reverse | 5′-CCAGCAGCACAGAGCAGGGC-3′ |

| #2 Forward | 5′-CGGAGGGGTGGCAAGAGAAG-3′ |

| #2 Reverse | 5′-ACAGGCATGCACTGCCATGC-3′ |

| #3 Forward | 5′-ACCTGAAAGCAGGTAAACTT-3′ |

| #3 Reverse | 5′-GGCTGGAACAAGCTCCATGT-3′ |

| Primers for CHOP binding site on PUMA promoter | |

| Forward | 5′-GACAAGTTCAGGAAGGACAGC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CGGAGGAGGTGAGTGAGTCA-3′ |

Tumor xenograft experiment

Animal Care Guidelines were strictly followed for all the animal experiments as established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Xiangya Hospital. Nude BALB/c mice were kept in a specific pathogen-free environment and allowed access to water and chow ad libitum. For longer than a week, the animals had free access to food and water and were allowed to acclimatize to the new environment. Mice (4–6-week old, female) were injected subcutaneously in both flanks with 5 × 105 WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells. After tumor growth for 1 week, mice were treated with 5-FU (25 mg/kg, every other day, i.p. injection), tazemetostat (125 mg/kg, daily, oral gavage), or their combination (n = 6) for 10 days. 5-FU were dissolved in 0.9% NaCl solution with 10% Tween-80 and 1% DMSO. Tazemetostat was suspended in 0.5% NaCMC with 0.1% Tween-80. Tumor volume was measured by calipers, and the volumes were calculated based on the formula: 0.5 × L × W2, where L, length; W, width. Mice were euthanized when tumors reached 1500 mm3 in size. Tumors were dissected and fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

After being subjected to an alcohol gradient, sections of the tumor specimens were embedded in paraffin and fixed in formalin and then rehydrated after deparaffination in xylene. Hydrogen peroxide (3% in distilled water) was used to block endogenous peroxidase for 15 min, and then, the samples were heated for 20 min at 100 °C for antigen retrieval. The slides with the tissue were incubated for 15 min using a universal blocking solution at room temperature and then maintained overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The IF was detected by using an AlexaFluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for detection.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad software VI (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used for all statistical analyses. To determine the significance between two groups, an unpaired t-test was used. One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey post hoc tests were performed to determine the significance in more than two groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

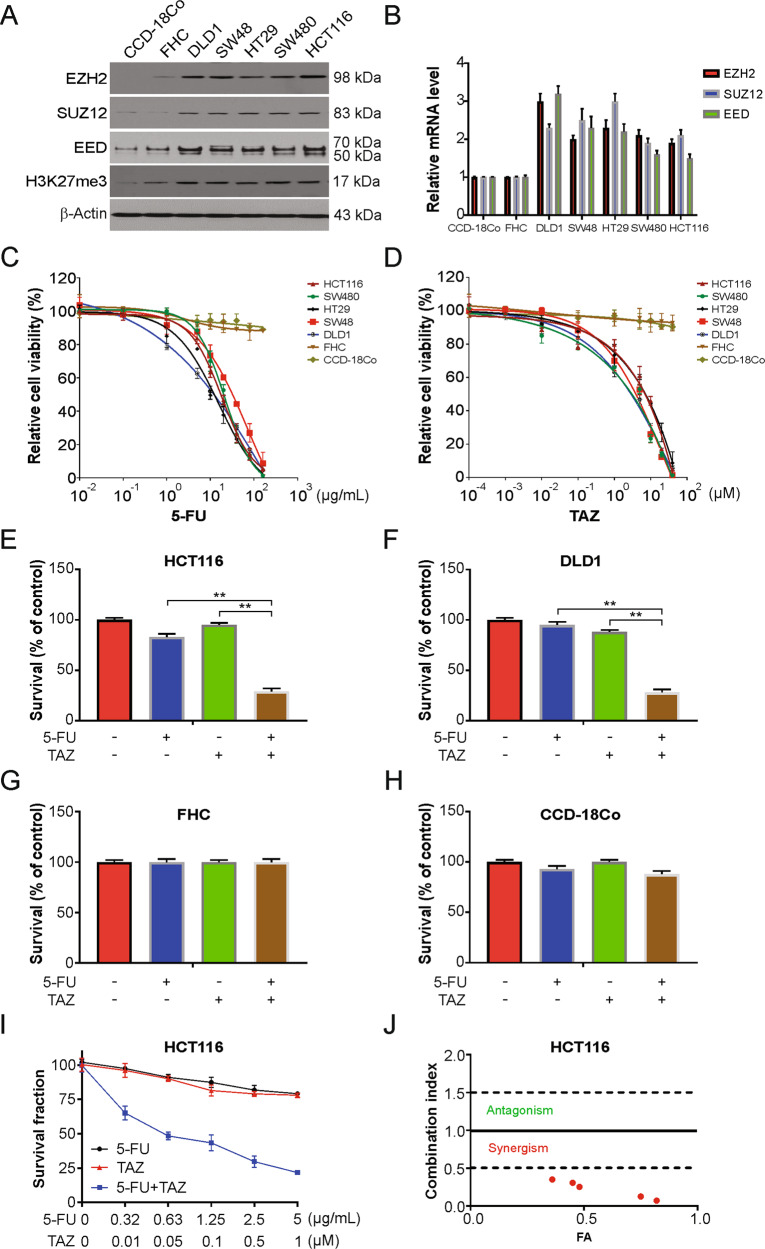

Tazemetostat increases the 5-FU sensitivity of the CRC cells

To investigate the synergistic effect of EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat and 5-FU in CRC cells, we first checked the level of EZH2, as well as other members of PRC2 complex including SUZ12 and EED in CRC cells using western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1A, when compared to CCD-18Co and FHC normal colon cells, these proteins were expressed at higher levels in the CRC cells. Moreover, the level of H3K27me3 increased in the CRC cells than in the normal colon cells (Fig. 1B). We next analyzed the level of EZH2 from the TCGA database. We found that the level of EZH2 was strikingly increased in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) and rectal adenocarcinoma (READ) compared to normal tissues (Fig. S1A–C).

Fig. 1. Tazemetostat enhanced the sensitivity of 5-FU in CRC cells.

A Western blotting of indicated proteins in the indicated cell lines. B mRNA level of indicated genes were analyzed by real-time PCR in the indicated cell lines. C Indicated cells were treated increasing dose of 5-FU for 24 h. Cell viability was analyzed by MTS. D Indicated cells were treated increasing dose of tazemetostat for 24 h. Cell viability was analyzed by MTS. E FHC cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 0.5 μM tazemetostat, or their combination for 24 h. Cell viability was analyzed by trypan blue. F CCD-18Co cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 0.5 μM tazemetostat, or their combination for 24 h. Cell viability was analyzed by trypan blue. G HCT116 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 0.5 μM tazemetostat, or their combination for 24 h. Cell viability was analyzed by trypan blue. H DLD1 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 0.5 μM tazemetostat, or their combination for 24 h. Cell viability was analyzed by trypan blue. I, J Sensitivity of HCT116 cells to 5-FU, tazemetostat, or their combination. Survival fraction (left) and the combination index (CI) (right) are shown. Fa, fraction affected. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01.

We next carried out a colorimetric MTS assay to identify the viability of the CRC cells post exposure to increasing dose of 5-FU, which was observed to induce the death of the CRC cells in a dose-dependent manner but not of the CCD-18Co and FHC normal colon cells (Fig. 1C). To examine whether 5-FU-induced apoptosis was enhanced by tazemetostat, we analyzed cell viability by MTS assay after treating the cells with tazemetostat for 24 h and found that tazemetostat did not induce the death of CCD-18Co and FHC cells (Fig. 1D), but induce the death of CRC cells in a dose-dependent manner. Further, the 5-FU and tazemetostat combination significantly increased the rate of cell death, as observed after the CRC cells were stained with trypan blue (Fig. 1E, F and Fig. S1D–H), and did not have any noticeable effect on the normal colon cells (Fig. 1G, H and Fig. S1I). Next, the extent of the synergistic effect of the FU-tazemetostat combination was assessed by a combination index (CI) generated using CompuSyn software, and as shown in Fig. 1I, J and Fig. S1J, K, a strong synergy was found in HCT116 and DLD1 cells. Therefore, tazemetostat increased the sensitivity of CRC cells to 5-FU.

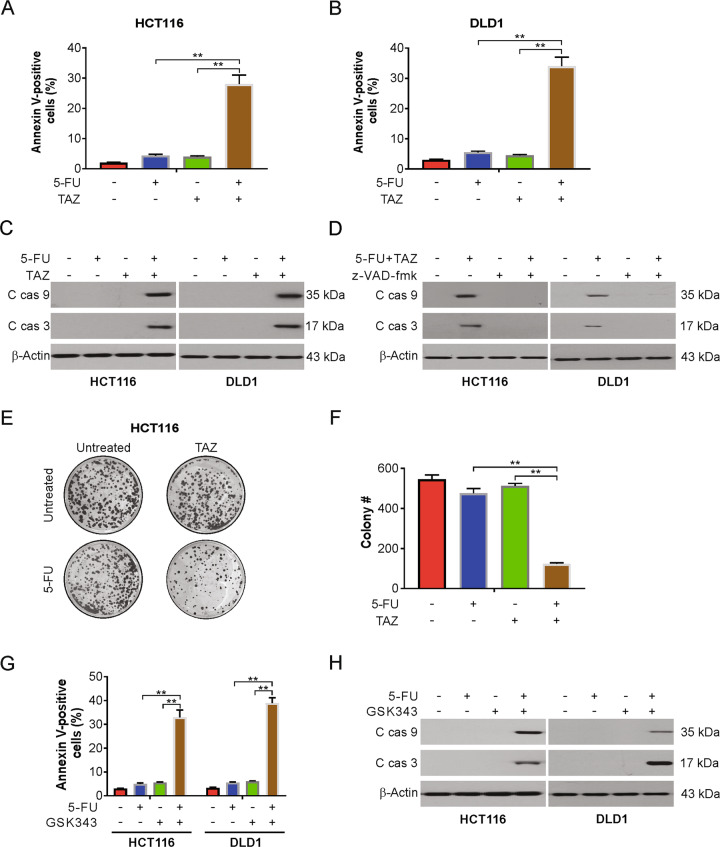

Tazemetostat increases the 5-FU-induced apoptosis in a p53-independent manner in CRC cells

Next, we investigated the mechanism of the synergizes of tazemetostat and 5-FU in CRC cells. Our findings indicated that tazemetostat enhanced 5-FU-induced apoptosis in HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Fig. 2A, B). We also found that the combination treatment increased the levels of cleaved caspase-3 and -9 (Fig. 2C). These results were confirmed by pretreating the cells with z-VAD-fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor, for 1 h to assess whether the combination induced caspase-dependent apoptosis. Indeed, the 5-FU-tazemetostat combination-induced caspase-3 and caspase-9 activities were reduced by z-VAD-fmk treatment (Fig. 2D). The long-term effect of tazemetostat, 5-FU single treatment, and their combination on cell proliferation revealed that the combination enhanced the inhibition of the colony-forming ability of the CRC cells (Fig. 2E, F). Moreover, GSK343, another EZH2 inhibitor, also sensitizes 5-FU-induced apoptosis in HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Fig. 2G, H). We next investigated the role of p53 in the combined effects of CRC cells. Our findings showed that the combination induces apoptosis in p53 WT (HCT116, SW48, SW480) and mutant (DLD1, HT29) cells, suggesting that the combination induces apoptosis in a p53-independent manner. To confirm the above results, we found that knocking down p53 cannot affect the combination-induced apoptosis (Fig. S2A, B). Taken together, our data demonstrated that the combination of tazemetostat and 5-FU-induced caspase-dependent apoptosis.

Fig. 2. Tazemetostat enhanced 5-FU-mediated apoptosis in CRC cells.

A, B HCT116 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 0.5 μM tazemetostat, or their combination for 24 h. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. C HCT116 or DLD1 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 0.5 μM tazemetostat, or their combination for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. D HCT116 or DLD1 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat with or without z-VAD-fmk pretreatment for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. E, F HCT116 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 0.5 μM tazemetostat, or their combination for 2 h. After 2 weeks, the plates were stained for cell colonies with crystal violet dye. G HCT116 or DLD1 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 1 μM GSK343, or their combination for 24 h. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. H HCT116 or DLD1 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU, 1 μM GSK343, or their combination for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01.

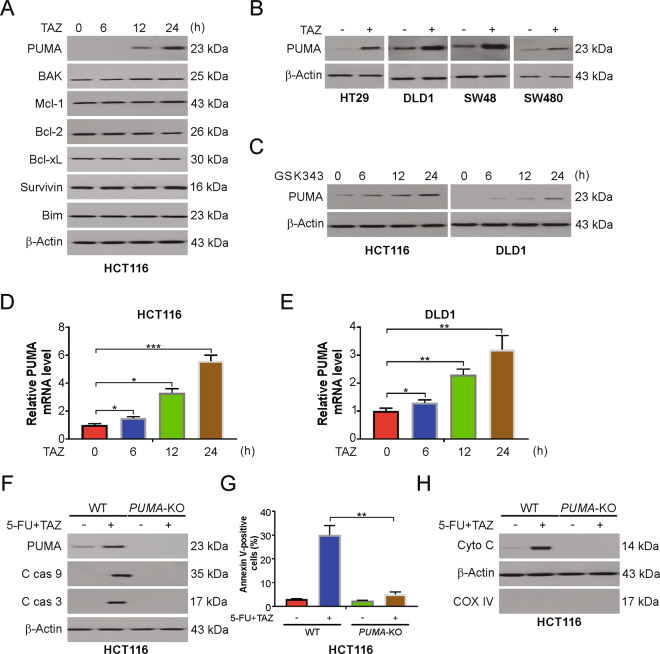

Tazemetostat promotes PUMA induction in CRC cells

To further examine the underlying mechanism of the increase in 5-FU sensitivity mediated by tazemetostat, we checked the levels of pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. We found that tazemetostat significantly increased the levels of proapoptotic proteins, PUMA and Bak (Fig. 3A). However, there was no change in the expression of the antiapoptotic Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, survivin, or Bcl-2. Tazemetostat-induced PUMA upregulation was observed in the HT29, DLD-1, SW48, and SW480 cells (Fig. 3B). GSK343 also induced PUMA upregulation in HCT116 and DLD1 cells in time-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). In addition, EZH2 deleption led to increased PUMA level (Fig. S3A), suggesting that tazemetostat-induced PUMA upregulation is an on-target effect. Furthermore, tazemetostat also induced PUMA mRNA expression in HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Fig. 3D, E). Next, PUMA expression was knocked out using the CRISPR-Cas 9 system to confirm the dependence of 5-FU/tazemetostat-induced apoptosis on PUMA. The PUMA knockout decreased the apoptosis-inducing effect of the 5-FU and tazemetostat combination. The caspase-3 and -9 cleavage levels were decreased in PUMA-KO HCT116 cells (Fig. 3F). Additionally, as determined by the FACS analysis, the apoptosis rate of the PUMA-KO HCT116 cells was markedly reduced (Fig. 3G). We further found that 5-FU/tazemetostat-induced cytochrome c release into the cytoplasm from the mitochondria was attenuated in the PUMA-KO HCT116 cells (Fig. 3H). WT and PUMA-KO DLD1 cells were treated with the combination of tazemetostat and 5-FU. The combination treatment induced apoptosis, caspase-3 and -9 activation, and cytochrome c release in WT DLD1 cells, but not in PUMA-KO DLD1 cells (Fig. S3B–S3D). Therefore, PUMA is required for tazemetostat to enhance 5-FU sensitivity.

Fig. 3. PUMA is required for tazemetostat/5-FU-induced apoptosis.

A HCT116 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat at indicated time points. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. B Indicated cell lines were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. PUMA expression was analyzed by western blotting. C HCT116 or DLD1 cells were treated with 1 μM GSK343 at indicated time points. PUMA expression was analyzed by western blotting. D HCT116 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat at indicated time points. mRNA level of PUMA was analyzed by real-time PCR. E DLD1 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat at indicated time points. mRNA level of PUMA was analyzed by real-time PCR. F WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. G WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. H Cytosolic fractions isolated from WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h were probed for cytochrome c by western blotting. β-actin and cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (Cox IV), which are expressed in cytoplasm and mitochondria, respectively, were analyzed as the control for loading and fractionation. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

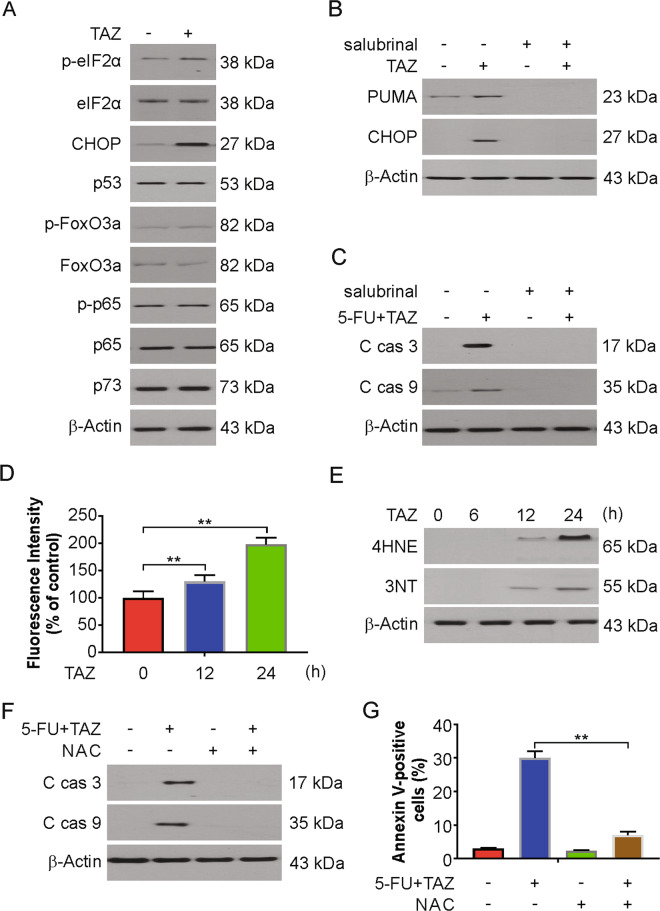

ROS/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress axis is required for tazemetostat-induced PUMA induction

Next, we investigated the mechanism of PUMA induction by tazemetostat in CRC cells. We tested whether tazemetostat regulates ER stress proteins since ER proteins induce the manifestation of PUMA29,30. Our findings demonstrated that tazemetostat increased CHOP and p-eIF2α levels in HCT116 cells (Fig. 4A). EZH2 depletion also induced CHOP and p-eIF2α upregulation in HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Fig. S4A, B). Consistent with a previous study31, we also found 5-FU-induced ER stress in HCT116 cells (Fig. S4C). We then pretreated the cells with an ER stress inhibitor, salubrinal, to confirm that ER stress increased the level of PUMA. ER stress inhibition remarkably reduced the tazemetostat-induced PUMA induction and the 5-FU and tazemetostat combination-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4B, C). We then analyzed the involvement of EZH2 in CHOP induction. We performed ChIP experiment with three primer pairs surrounding the core promoter and upstream region of CHOP gene (Fig. S4D). Our findings indicated that EZH2 binds to CHOP promoter (Fig. S4E). However, tazemetostat treatment had no effect on the binding of EZH2 to the CHOP promoter (Fig. S4E). Furthermore, ChIP assay with H3K27me3 was performed. As expected, no effect of H2K27me3 on CHOP promoter locus post tazemetostat treatment was observed (Fig. S4F). Therefore, our results indicated that CHOP is not regulated by EZH2 directly.

Fig. 4. Tazemetostat-induced PUMA via ROS/ER stress axis.

A HCT116 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. B HCT116 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat, 1 μM salubrinal or their combination for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. C HCT116 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat with or without salubrinal for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. D HCT116 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 12 or 24 h. The expression levels of ROS were measured by DHE staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. E HCT116 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. F HCT116 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat with or without NAC for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. G HCT116 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat with or without NAC for 24 h. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01.

Previous study has shown that ER stress can be induced by ROS32. Therefore, we hypothesized that ROS may also cause ER stress by tazemetostat stimulation. To estimate this effect, the levels of ROS generated by DHE were measured, and the results showed a significant ROS increase in the tazemetostat-treated system (Fig. 4D). Tazemetostat further increased the levels of 4HNE and 3NT, markers of oxidative stress (Fig. 4E). Consistent with previous studies33,34, 5-FU treatment increased ROS generation, as well as 4HNE and 3NT induction (Fig. S4G, H). To further examine whether ROS contributed to the synergistic 5-FU and tazemetostat combination treatment, cells were pretreated with the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; 5 mmol/L). The apoptotic protein levels were enhanced by the combination and reduced after NAC treatment (Fig. 4F), a finding confirmed by FACS analysis (Fig. 4G). These results demonstrated that tazemetostat enhances 5-FU sensitivity via the activation of ROS/ER stress.

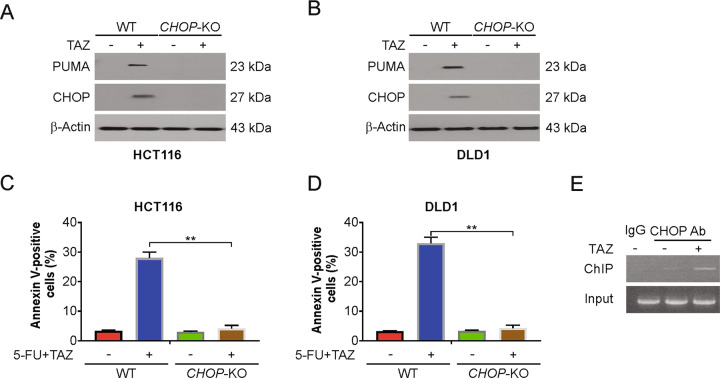

CHOP is required for tazemetostat-induced PUMA upregulation

A previous study has shown that CHOP regulates PUMA expression in islets with ER stress35. Therefore, we determined whether CHOP is required for tazemetostat-induced PUMA upregulation. Knocking out CHOP abrogated the tazemetostat-induced PUMA induction of the HCT116 cells (Fig. 5A) and the DLD1 cells (Fig. 5B). The increased apoptosis rate induced by tazemetostat was suppressed in CHOP-KO HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Fig. 5C, D). Furthermore, CHOP was found by ChIP analysis to be recruited to the PUMA promoter following tazemetostat treatment (Fig. 5E). A previous study has shown that EZH2 directly binds to the promoter region of PUMA gene36. Therefore, we then analyzed if CHOP and EZH2 complete for binding PUMA promoter. In WT HCT116 cells, tazemetostat treatment suppressed the binds of EZH2 on PUMA promoter locus. However, in the CHOP-KO cells, tazemetostat-induced EZH2 accumulation on PUMA promoter was attenuated (Fig. S5A, B). Next, ChIP assay with H3K27me3 antibody was performed. Our findings indicated that tazemetostat treatment decreased H3K27me3 at the PUMA locus, which was attenuated in CHOP-KO cells (Fig. S5C). These results indicate that CHOP directly binds to the PUMA promoter and complete with EZH2 to drive its transcriptional activation in response to tazemetostat treatment.

Fig. 5. CHOP mediated tazemetostat-induced PUMA upregulation.

A WT and CHOP-KO HCT116 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. B WT and CHOP-KO DLD1 cells were treated with 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. C WT and CHOP-KO HCT116 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. D WT and CHOP-KO DLD1 cells were treated with the combination of 2.5 μg/mL 5-FU and 0.5 μM tazemetostat for 24 h. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. E Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using anti-CHOP antibody on HCT116 cells following tazemetostat (0.5 μM) treatment for 12 h. The IgG was used to control for antibody specificity. PCR was carried out using primers surrounding the CHOP binding sites in the PUMA promoter. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01.

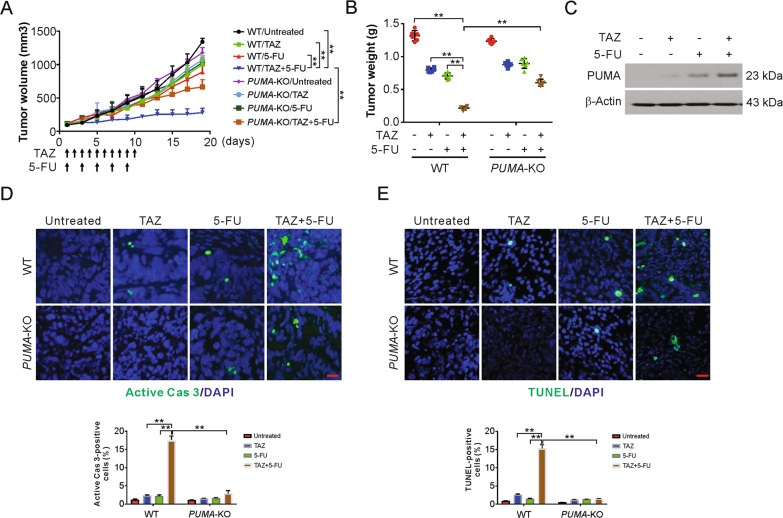

PUMA mediates the chemosensitization effect of tazemetostat in xenograft mouse model

To examine if PUMA mediates the antitumor effect of tazemetostat and 5-FU in xenograft, nude mice with WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 tumors were treated with tazemetostat, 5-FU, or their combination. The combination treatment in the mice more significantly reduced the tumor growth in contrast to that in the control or single treatments (Fig. 6A). Further, the combination group had markedly reduced tumor weight than the other groups (Fig. 6B). However, the enhanced tumor reduction was absent in PUMA-KO tumors (Fig. 6A, B). Subsequently, western blotting confirmed that, similar to the in vitro observations, PUMA expression was increased after tazemetostat alone or with 5-FU (Fig. 6C and Fig. S6A). There was no adverse effect on body weight following treatment with tazemetostat, 5-FU, and their combination (Fig. S6B). In addition, apoptosis induction, analyzed by active caspase 3 and TUNEL staining, by the combination treatment was also suppressed in the PUMA-KO tumors compared with WT tumors (Fig. 6D, E). Moreover, Ki67 staining results shown that PUMA-KO had no effect on the combination induced proliferation suppression (Fig. S6C). Altogether, these data suggest that the combination of 5-FU and tazemetostat induced PUMA-dependent apoptosis in vivo.

Fig. 6. The antitumor effects of regorafenib in vivo are PUMA-dependent.

A Nude mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 WT or PUMA-KO HCT116 cells. After 1 week, mice were treated with tazemetostat, 5-FU, or their combination as indicated. Tumor volume at indicated time points after treatment was calculated and plotted with P values, n = 6 in each group. B At the end of the treatment, the mice were sacrificed and the tumors were removed and weighed. C Mice were treated with tazemetostat, 5-FU, or their combination as in (A) for 4 consecutive days. The PUMA expression in the indicated tumors were analyzed by western blotting. D Mice were treated with tazemetostat, 5-FU, or their combination as in (A) for 4 consecutive days. Paraffin-embedded sections of WT or PUMA-KO tumor tissues were analyzed by active caspase 3 staining. Active caspase 3-positive cells were counted and plotted. E Mice were treated with tazemetostat, 5-FU, or their combination as in (A) for 4 consecutive days. Paraffin-embedded sections of WT or PUMA-KO tumor tissues were analyzed by TUNEL staining. TUNEL-positive cells were counted and plotted. The results were expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Many studies have concentrated on drug sensitivity by combining natural products and chemotherapy37. 5-FU is a widely used antitumor drug and plays a key role in the treatment of CRC and other types of cancers, such as breast cancer and head and neck cancer38. 5-FU is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound whose structure is similar to that of pyrimidine molecules DNA and RNA39. Due to its structure, 5-FU can interfere with the metabolism of nucleoside and can be incorporated into RNA and DNA, leading to cytotoxicity and cell death40. After 5-FU treatment alone, the overall remission rate of CRC is only 10–15%, while the combination of 5-FU and other antitumor drugs can only increase the remission rate to 40–50%41,42. Therefore, new strategies for treatment and drug resistance reversal are urgently needed.

PRC2 uniquely mediates H3K27 mono-, di-, or trimethylation, which is designated by the EZH2 SET domain43. Mice with non-functional Ezh2 display severe defects in cell proliferation and other developmental abnormalities44. The differentiation of potential cancer stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells was suppressed by EZH2 via the H3K27me3 mark45. Point mutations that increase the catalytic activity of EZH2 may facilitate the transformation in B-cell neoplasms46, thus, positioning EZH2 as a promising target for a patient population with this genetic constitution. In human models of B-cell lymphoma xenografts, EZH2 inhibitors exhibited strong antitumor effects47.

This study investigated the synergism of a tazemetostat and 5-FU treatment to enhance CRC treatment. Indeed, in this study, 5-FU along with tazemetostat remarkably suppressed the viability of the cells and induced apoptosis dependent on caspase in the CRC cells, with no observable difference in the normal colon cells. Further, this combination reduced tumor volume and increased the apoptotic rate of cells in the xenograft model. Therefore, 5-FU along with tazemetostat may decrease the negative side effects of 5-FU and enhance its cytotoxicity. This synergism in CRC cell lines may be due to the upregulation of PUMA, a proapoptotic protein.

Apoptosis mainly follows an intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathway48. The intrinsic pathway is regulated by the equilibrium between proteins favoring apoptosis (Bax, Bak, and PUMA) and proteins stalling the action of apoptotic proteins (Bcl-xL and Bcl-2) in the Bcl-2 family49. PUMA upregulation triggers the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and induces apoptosome formation and caspase-3 activation, thus inducing apoptosis50. Our results also show the importance of PUMA for increasing the sensitivity of 5-FU. Alternatively, the knockout of PUMA reduced the tazemetostat-induced increase of 5-FU-induced cell sensitivity.

During protein synthesis, folding, and trafficking, the ER plays vital roles51. When many unfolded proteins are created in the ER lumen, ER stress occurs52. The unfolded proteins and ER stress-related genes are activated in cells under these stressful environmental conditions52. Usually, oxidative agents that modulate the survival of cancer cells induce ER stress53. In this study, we found that tazemetostat-induced ER stress markedly enhanced PUMA expression via the induction of the ER stress/CHOP/PUMA pathway in the CRC cell lines. Additionally, ROS are produced by mitochondria and NADPH oxidase, and the increased production of ROS can be directly attributed to the increase in PUMA level due to ER stress54. The initiation and progression of cancer involve ROS as important players54. Cancer cells have higher levels of ROS than normal cells. Thus, cancer cells are more susceptible to acute oxidative stress induction. In our study, we observed that tazemetostat induced ROS generation, and ROS quenching by NAC weakens the tazemetostat-mediated rise in the levels of CHOP and PUMA. NAC protects against DNA damage and carcinogenesis and participates in antioxidant functions. This protection facilitates the coordination of the DNA damage and amount of ROS production by the platinum agents that are used in anticancer drugs. ROS quenching reduces the cell death induced by the tazemetostat and 5-FU combination. Therefore, tazemetostat-induced ROS play a key role in 5-FU sensitivity.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that the combination treatment of 5-FU and tazemetostat produces noticeable synergistic effects in CRC cell lines xenograft mouse model. ROS/ER stress/PUMA signaling pathway activation paved the way for heightened apoptotic potential and formed the basis for the combination synergy. Our results showed that the combined treatment of 5-FU and tazemetostat may be a groundbreaking CRC treatment strategy.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Science Foundation of China (82002616 to X.T.).

Author contributions

X.T. and J.S.T. developed the hypothesis and designed the experiments. X.T., Z.Z., P.L., H.L., and L.F. S. performed experiments and statistical analyses. X.T., H.Y., and J.S.T. wrote the main manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by N. Barlev

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-05764-6

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/29/2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: 10.1038/s41419-023-05764-6

Contributor Information

Xiao Tan, Email: tanx206@163.com.

Jing-Shan Tong, Email: tongjingshan@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-020-03266-3).

References

- 1.Xie YH, Chen YX, Fang JY. Comprehensive review of targeted therapy for colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020;5:22. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0116-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang CM, et al. Role of deficient mismatch repair in the personalized management of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13:892. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McQuade RM, Stojanovska V, Bornstein JC, Nurgali K. Colorectal cancer chemotherapy: the evolution of treatment and new approaches. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017;24:1537–1557. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170111152436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Jeught K, Xu HC, Li YJ, Lu XB, Ji G. Drug resistance and new therapies in colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3834–3848. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i34.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francipane MG, Bulanin D, Lagasse E. Establishment and characterization of 5-fluorouracil-resistant human colorectal cancer stem-like cells: tumor dynamics under selection pressure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1817. doi: 10.3390/ijms20081817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golshani G, Zhang Y. Advances in immunotherapy for colorectal cancer: a review. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820917527. doi: 10.1177/1756284820917527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond WA, Swaika A, Mody K. Pharmacologic resistance in colorectal cancer: a review. Therap. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2016;8:57–84. doi: 10.1177/1758834015614530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danese E, Montagnana M. Epigenetics of colorectal cancer: emerging circulating diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017;5:279. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.04.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patnaik S, Anupriya Drugs targeting epigenetic modifications and plausible therapeutic strategies against colorectal cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:588. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gan L, et al. Epigenetic regulation of cancer progression by EZH2: from biological insights to therapeutic potential. Biomark. Res. 2018;6:10. doi: 10.1186/s40364-018-0122-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim KH, Roberts CW. Targeting EZH2 in cancer. Nat. Med. 2016;22:128–134. doi: 10.1038/nm.4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Au SL, Wong CC, Lee JM, Wong CM, Ng IO. EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 is involved in epigenetic repression of deleted in liver cancer 1 in human cancers. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao H, Xu Y, Mao Y, Zhang Y. Effects of EZH2 gene on the growth and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2013;2:78–83. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2012.12.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim W, et al. Targeted disruption of the EZH2-EED complex inhibits EZH2-dependent cancer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:643–650. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jani KS, et al. Histone H3 tail binds a unique sensing pocket in EZH2 to activate the PRC2 methyltransferase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:8295–8300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819029116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu J, Wang Z, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhang L. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627984100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang LN, Li JY, Xu W. A review of the role of Puma, Noxa and Bim in the tumorigenesis, therapy and drug resistance of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:1–7. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2012.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu J, Zhang L. PUMA, a potent killer with or without p53. Oncogene. 2008;27:S71–S83. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CL, Blum JM, Kirsch DG. Role of p53 in regulating tissue response to radiation by mechanisms independent of apoptosis. Transl. Cancer Res. 2013;2:412–421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.You H, et al. FOXO3a-dependent regulation of Puma in response to cytokine/growth factor withdrawal. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1657–1663. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P, et al. PUMA is directly activated by NF-kappaB and contributes to TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1192–1202. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cazanave SC, et al. CHOP and AP-1 cooperatively mediate PUMA expression during lipoapoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G236–G243. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00091.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melino G, et al. p73 Induces apoptosis via PUMA transactivation and Bax mitochondrial translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8076–8083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong J, Tan S, Zou F, Yu J, Zhang L. FBW7 mutations mediate resistance of colorectal cancer to targeted therapies by blocking Mcl-1 degradation. Oncogene. 2017;36:787–796. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan X, et al. BET inhibitors potentiate chemotherapy and killing of SPOP-mutant colon cancer cells via induction of DR5. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1191–1203. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang X, et al. DYNLT3 is required for chromosome alignment during mouse oocyte meiotic maturation. Reprod. Sci. 2011;18:983–989. doi: 10.1177/1933719111401664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, et al. ERK3 is required for metaphase-anaphase transition in mouse oocyte meiosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan S, et al. PUMA mediates ER stress-induced apoptosis in portal hypertensive gastropathy. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1128. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein inhibits apoptosis by modulating endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Oncotarget. 2017;8:96027–96034. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yadunandam AK, Yoon JS, Seong YA, Oh CW, Kim GD. Prospective impact of 5-FU in the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, modulation of GRP78 expression and autophagy in Sk-Hep1 cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2012;41:1036–1042. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeeshan HM, Lee GH, Kim HR, Chae HJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and associated ROS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:327. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida K, et al. Preventive effect of Daiokanzoto (TJ-84) on 5-fluorouracil-induced human gingival cell death through the inhibition of reactive oxygen species production. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang KA, et al. Epigenetic modification of Nrf2 in 5-fluorouracil-resistant colon cancer cells: involvement of TET-dependent DNA demethylation. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1183. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wali JA, et al. The proapoptotic BH3-only proteins Bim and Puma are downstream of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial oxidative stress in pancreatic islets in response to glucotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1124. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, et al. EZH2-mediated Puma gene repression regulates non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation and cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56338–56354. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bayat Mokhtari R, et al. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:38022–38043. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deboever G, Hiltrop N, Cool M, Lambrecht G. Alternative treatment options in colorectal cancer patients with 5-fluorouracil- or capecitabine-induced cardiotoxicity. Clin. Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noordhuis P, et al. 5-Fluorouracil incorporation into RNA and DNA in relation to thymidylate synthase inhibition of human colorectal cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2004;15:1025–1032. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponce-Cusi R, Calaf GM. Apoptotic activity of 5-fluorouracil in breast cancer cells transformed by low doses of ionizing alpha-particle radiation. Int J. Oncol. 2016;48:774–782. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei Y, Yang P, Cao S, Zhao L. The combination of curcumin and 5-fluorouracil in cancer therapy. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018;41:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12272-017-0979-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klaassen U, Wilke H, Harstrick A, Seeber S. Fluorouracil-based combinations in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Oncol. 1998;12:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hock H. A complex Polycomb issue: the two faces of EZH2 in cancer. Genes Dev. 2012;26:751–755. doi: 10.1101/gad.191163.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Carroll D, et al. The polycomb-group gene Ezh2 is required for early mouse development. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;21:4330–4336. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4330-4336.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen Y, Cai J, Hou Y, Huang Z, Wang Z. Role of EZH2 in cancer stem cells: from biological insight to a therapeutic target. Oncotarget. 2017;8:37974–37990. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo M, et al. EZH2 represses the B cell transcriptional program and regulates antibody-secreting cell metabolism and antibody production. J. Immunol. 2018;200:1039–1052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beguelin W, et al. EZH2 is required for germinal center formation and somatic EZH2 mutations promote lymphoid transformation. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:677–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulda S, Debatin KM. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:4798–4811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Arcy MS. Cell death: a review of the major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Cell Biol. Int. 2019;43:582–592. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ming L, Wang P, Bank A, Yu J, Zhang L. PUMA dissociates Bax and Bcl-X(L) to induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16034–16042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwarz DS, Blower MD. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73:79–94. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao SS, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in cell fate decision and human disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;21:396–413. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forrester SJ, Kikuchi DS, Hernandes MS, Xu Q, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species in metabolic and inflammatory signaling. Circ. Res. 2018;122:877–902. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.