Abstract

The origin and zoonotic transmission route of SARS-CoV-2 remain speculative. We discuss scenarios for the zoonotic emergence of SARS-CoV-2, and also explore the missing evidence and ecological considerations that are necessary to confidently identify the origin and transmission route of SARS-CoV-2 and to prevent future pandemics of zoonotic viruses.

Speculations about the Origin of SARS-CoV-2

In December 2019 a human outbreak of pneumonia, later named coronavirus disease (COVID-19), began spreading across the planet, infecting millions of people. The causative agent of COVID-19 was quickly identified as a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Some of the earliest cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan clustered around a local seafood market, giving rise to speculations about an animal origin for the virus, with the possibility that it may have crossed the species barrier to infect humans (zoonotic event , see Glossary) in the market [1].

Earlier this year, researchers in China isolated and sequenced the genome of SARS-CoV-2 [1,2]. On comparison with other CoV sequences, two bat SARS-related coronaviruses (SARSr-CoV), RaTG13 and RmYN02, were identified as the closest known ancestors of SARS-CoV-2. RaTG13, identified in intermediate horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus affinis) in Yunnan, China exhibits 96.2% sequence identity to SARS-CoV-2 at the whole-genome level and clusters with SARS-CoV-2 in phylogenetic analysis [1]. RmYN02, identified in Malayan horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus malayanus) from Yunnan is 93.3% identical to SARS-CoV-2 at the whole-genome level [3]. These SARSr-CoVs in bats could represent the evolutionary source of SARS-CoV-2. Alternatively, SARSr-CoVs detected in bats could represent a clade that evolved independently from a common ancestor of SARS-CoV-2. We discuss recent data that shed light on possible zoonotic origins of SARS-CoV-2, and speculate on evolutionary and spillover scenarios that may have played a role in its emergence.

Evidence Hinting at a Bat Origin

Although close evolutionary relationships to bat CoVs suggest a bat origin for SARS-CoV-2, our understanding is notably limited by the scarcity of available sequenced CoV genomes. These genomes represent a mere fraction of the natural CoV diversity. One may conclude that closer relatives to SARS-CoV-2 are likely to exist, but have not yet been sequenced, which raises the question – is 96.2% genomic identity between strains sufficient to confidently identify a reservoir host? For example, palm civets (Paguma larvata), the likely animal source of the SARS outbreak in 2002–2003, carried a SARS-CoV-related virus that was 99.8% identical to SARS-CoV [4]. CoVs highly homologous to SARS-CoV-2 have not been identified in any animal host, but detection of SARS-CoV-2 in an animal species in the future could be confounded by the possibility of zooanthroponosis. Recent phylogenetic analyses indicate that SARSr-CoVs likely diverged from an ancestral bat-derived CoV between 1948 and 1982 [5], suggesting that SARSr-CoVs have been circulating in selected bat species for some time. The order Chiroptera represents >1400 species of bats, and emerging theoretical and experimental data suggest that not all bat species may support SARS-CoV-2 replication [6]. It is also possible that a SARSr-CoV evolved into SARS-CoV-2 in humans after spilling over from an animal source, followed by rapid transmission of this human-adapted strain [7]. Theories on laboratory escape of existing SARSr-CoVs have no valid supportive evidence. Despite these speculations, the transmission route of SARS-CoV-2 or SARSr-CoV from bats to humans, either directly or through an intermediate animal species, remains elusive (Figure 1 ).

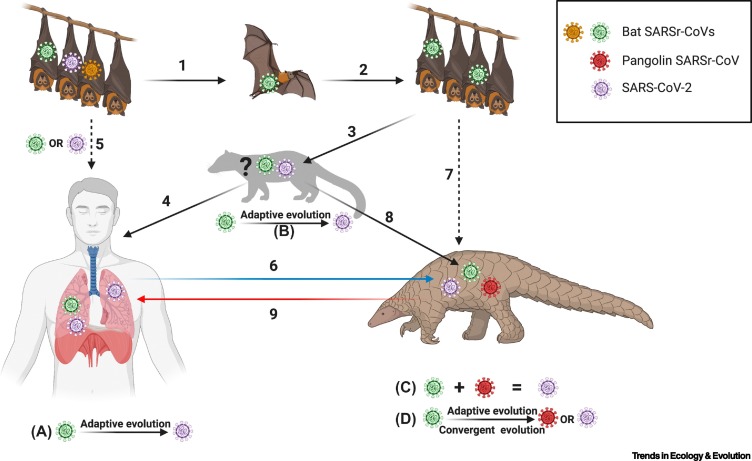

Figure 1.

Possible Scenarios for the Origin of SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-related coronaviruses (SARSr-CoVs) have been circulating in selected species of bats. It is possible that SARS-CoV-2 remains undiscovered in bats (1). Bats may spread CoVs within bat populations without causing clinical signs of disease (2). Owing to unknown factors, bats may occasionally shed CoVs. Bat SARSr-CoVs may infect humans directly (5) or via an intermediate host (3 and 4), and select for human-adapted strains such as SARS-CoV-2 through adaptive evolution (5; scenario A). A bat SARSr-CoV could have evolved into SARS-CoV-2 in bats before spilling over into humans (5). Alternatively, bat SARSr-CoVs may infect other mammalian intermediate species that remain to be discovered (3) (? indicates an undiscovered intermediate host), and the virus may undergo adaptive evolution in these animals (scenario B). Virus species with enhanced fitness, such as SARS-CoV-2, could then infect humans that are in close contact with the intermediate animal host (4). Pangolins could have been infected with a bat SARSr-CoV, either directly (7) or via an undiscovered intermediate host (8), leading to recombination events between existing pangolin SARSr-CoVs and bat SARSr-CoVs to generate SARS-CoV-2 (scenario C). The recombined virus could have then spilled over into humans (9). Alternatively, pangolins could have been infected with SARSr-CoVs from bats (6 or 7), followed by adaptive or convergent evolution (scenario D) to generate pangolin SARSr-CoVs and/or SARS-CoV-2. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Are Pangolins Intermediate Hosts?

Two independent studies identified SARSr-CoVs in confiscated Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica), whereas confiscated Chinese pangolins (Manis pentadactyla) tested negative [8,9] (Table 1 ). Both Lam and Xiao et al. isolated SARSr-CoVs from pangolins that were confiscated during illegal wildlife trade. Importantly, CoVs isolated from these pangolins were only 85.5–92.4% similar to SARS-CoV-2 at the whole-genome level [8], but possess intriguing similarities to SARS-CoV-2 in regions that are crucial for interaction with the human cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

Table 1.

Detection of SARSr-CoVs in Pangolins

| Common name | Species | Number positive for CoV | Tissue or sample tested | Source | Percent sequence identity to SARS-CoV-2 (whole genome) | Health status | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese pangolins | Manis pentadactyla | 0/4 | Lung | Wildlife rescue center, Guangdong | No CoV detected | Not examined | [9] |

| Malayan pangolins | Manis javanica | 17/25a | Lung | Wildlife rescue center, Guangdong | 81.60% | Respiratory disease with alveolar damage, emaciation, lack of appetite, inactivity | [9] |

| Malayan pangolins | Manis javanica | 5/18 | Lung, intestine, blood | Guangxi customs office | 85.5–92.4% | Dead | [8] |

| Malayan pangolins | Manis javanica | 2/11a | Lung, lymph, spleen | Guangdong wildlife rescue center | Not compared at the time | Dead | [11] |

| Malayan pangolins | Manis javanica | 3/27a | Lung, lymph, spleen | Guangdong wildlife rescue center | 90.32% | Severe respiratory disease | [10] |

| Malayan pangolins | Manis javanica | 0/334 | Throat and rectum swabs | Peninsular Malaysia; Sabah, Malaysia | No CoV detected | Weak only | [13] |

Overlap between samples.

The receptor-binding domain (RBD) within the CoV spike protein makes key contacts with ACE2 to facilitate viral entry. One pangolin SARSr-CoV RBD is 97.4% identical to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may have either acquired the RBD from pangolin CoVs via recombination or developed this similarity through convergent evolution [8,9] (Figure 1). CoVs are prone to recombination, but a recent study reported an absence of any evidence for recombination in the spike proteins of CoVs in the lineage leading to SARS-CoV-2 and other related Sarbecoviruses [5]. Thus, the origin of a pangolin SARSr-CoV-like RBD in SARS-CoV-2 remains a mystery (Figure 1).

Intermediate hosts play an important role in the amplification and adaptation of zoonotic viruses. An ideal intermediate reservoir host does not develop severe disease on infection with a virus, a key feature that allows a virus to multiply and seek alternative hosts without killing its evolutionary host. However, SARSr-CoV-infected pangolins in two studies demonstrated clinical signs of disease, including histological changes and severe respiratory disease (Table 1) [9,10], observations that are inconsistent with pangolins being a successful intermediate reservoir. Because the sampled pangolins were either dead or extremely sick when specimens were collected (Table 1), and Koch’s postulates have not been established for SARSr-CoVs in pangolins, it is possible that other underlying factors produced disease symptoms in these animals. The presence of disease symptoms in infected pangolins is further complicated by the likely presence of other viruses such as Sendai virus [11]. The sampled pangolins could have also been exposed to CoVs by other animal species or humans along the wildlife trade route [12] (Figure 1). Recent data from surveillance of 334 Malayan/Sunda pangolins (Manis javanica) failed to detect CoV genetic material, raising further doubts about the role of pangolins as natural intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2 [13].

There is evidence suggesting that particular species of pangolins (Smutsia gigantea and Phataginus tricuspis) and bats (Hipposideridae spp., Emballonuridae spp. and Miniopterus spp.) cohabitat in a natural setting, such as in underground caves, which may facilitate the exchange of CoVs, although there was no evidence of CoV infection in this study [14] (Figure 1). Rhinolophid bats and pangolins also share some dietary overlap (e.g., termites), which may facilitate exchange of viruses; however, direct transmission via insects is unlikely. Indeed, full examination of bat and pangolin CoV susceptibility, species dependencies, and their ecological overlap will be needed before drawing conclusions about enzootic transmission cycles.

Interconnectedness of Ecosystem Health and Virus Spillover

There are currently only speculations about the origins of SARS-CoV-2, and direct evidence is lacking. Genetic evidence suggests that birds are the ancestral source of Delta- and Gammacoronaviruses, whereas bats are the original source for all Alpha- and Betacoronaviruses. However, it remains uncertain whether a bat species was only involved in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 or also mediated direct bat-to-human transmission. Identifying the wildlife source of SARS-CoV-2 will help to prevent future and/or ongoing zoonotic transmission events. Such ongoing transmission currently exists, given continued Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) spillover from camels to humans. Although current research focuses on tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a need to broaden our wildlife surveillance efforts to identify viruses with zoonotic potential.

Ecological factors may also promote the spillover of wildlife-borne viruses. For example, nutritional and reproductive stresses are associated with increased Hendra virus replication in bats [15]. Factors such as urbanization, deforestation and forest fragmentation, mixed farming practices, and other anthropogenic interference with wildlife habitats may indeed alter the delicate balance that reservoir species have evolved with their viruses. In addition, animal stress from unsustainable livestock industries, wildlife trade, and artificial co-housing of different animal species provides pathogens with the opportunity to find novel alternative hosts that are unlikely to occur in a natural setting. Indeed, investment in science with a One Health focus will tackle future emerging zoonoses and closely monitor ecosystem health to limit human interference and minimize exposure across the human–wildlife interface.

Glossary

- Adaptive evolution

the accumulation of advantageous mutations while propagating in a host.

- Convergent evolution

the independent evolution of similar mutations or traits in different species.

- Enzootic

the presence of disease within animal populations in a region.

- Koch’s postulates

four criteria for establishing a causal relationship between a pathogen and a disease.

- Phylogenetic analysis

the study of evolutionary relationships.

- Zooanthroponosis

human-to-animal transmission of a disease or pathogen.

- Zoonotic event

transmission of a pathogen from animal to humans.

References

- 1.Zhou P., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu F., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou H., et al. A novel bat coronavirus closely related to SARS-CoV-2 contains natural insertions at the S1/S2 cleavage site of the spike protein. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:2196–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan Y., et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boni M.F., et al. Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:1408–1417. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan H., et al. Many bat species are not potential hosts of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2: evidence from ACE2 receptor usage. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.09.08.284737. Published online September 8, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y.Z., Holmes E.C. A genomic perspective on the origin and emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020;181:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam T.T., et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583:282–285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao K., et al. Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583:286–289. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu P., et al. Are pangolins the intermediate host of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)? PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu P., et al. Viral metagenomics revealed Sendai virus and coronavirus infection of Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica) Viruses. 2019;11:979. doi: 10.3390/v11110979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han G.Z. Pangolins harbor SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2020;28:515–517. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J., et al. No evidence of coronaviruses or other potentially zoonotic viruses in Sunda pangolins (Manis javanica) entering the wildlife trade via Malaysia. Ecohealth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10393-020-01503-x. Published online November 23, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann D., et al. Pangolins and bats living together in underground burrows in Lope National Park, Gabon. Afr. J. Ecol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/aje.12759. Published online Jun 17, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plowright R.K., et al. Reproduction and nutritional stress are risk factors for Hendra virus infection in little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus) Proc. Biol. Sci. 2008;275:861–869. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]