Abstract

Increasing evidence supports a positive association between periodontal disease and total cancer risk. We evaluated the association of clinically-assessed periodontal disease and a consequence, edentulism with total cancer mortality in participants without a prior cancer diagnosis in a US nationally representative population.

Included were 6,034 participants aged ≥40 years without a prior cancer diagnosis who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Periodontal health was measured by trained dentists. Cancer deaths (n = 702) were ascertained during a median of 21.3 years of follow-up. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the association of periodontal disease and edentulism with total cancer mortality using no periodontal disease/dentate as the reference and adjusting for potential demographic, lifestyle including smoking, and social factor confounders.

15% had periodontitis and 17% were edentulous. Periodontitis was not statistically significantly associated with risk of total cancer death after multivariable adjustment. Edentulism was associated with an increased risk of cancer mortality (hazard ratio=1.50, 95% confidence interval=1.12 to 2.00) after multivariable adjustment, including in men and women and in each racial/ethnic group studied. The positive association was observed in overweight/obese participants but not participants with normal body mass index, more strongly in pre/diabetic participants than in participants without diabetes, and in ever cigarette smokers but not never cigarette smokers.

In this US nationally representative population, those with edentulism, but not periodontal disease, had a higher risk of total cancer death, especially in those with shared risk factors for periodontal disease and cancer.

Keywords: periodontal disease, edentulism, cancer, mortality

Introduction

Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory condition caused by bacterial infection of the supporting gum and bone tissues around the teeth1, 2. A common consequence of severe periodontal disease is tooth loss and edentulism3. There has been increasing interest in understanding the relationship between this inflammatory condition and inflammation-associated chronic diseases, including cancer.

Although the underlying mechanisms are unknown, periodontal disease may influence cancer risk through acute systemic inflammation, pathogen invasion into blood circulation, and/or chronic changes in immune response4, 5. Several meta-analyses have examined the association between periodontal disease and cancer risk and/or mortality, and results consistently suggest that people with periodontal disease or tooth loss have a higher cancer risk3, 6, 7. However, some of these studies assessed periodontal disease and tooth loss by self report, or did not adjust important confounders such as smoking, and none of these studies investigated total cancer death in the general US population.

Given that 42% of dentate US adults aged 30 years and older have mild or worse periodontal disease (7.8% severe)8, 9 and that 4.9% of those 15 years and older are edentulous8, 9, and given the substantial cancer burden8, 9, the influence of periodontal disease and edentulism on cancer mortality should to be investigated in general populations. Using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III, a US nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized Americans, and its linked mortality data, we evaluated the association of clinically-assessed periodontal disease and edentulism with total cancer mortality in participants aged 40 and older without a prior cancer diagnosis. We hypothesized that participants with periodontal disease or edentulism, would have a higher risk of cancer death even after taking into account social factors and shared risk factors for periodontal disease and cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study population

NHANES is a series of cross-sectional studies conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The present analysis included data from participants in NHANES III, which was conducted from 1988–1994 at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes3/Default.aspx10. NHANES III utilized a multistate stratified probability sample with oversampling of Hispanics, non-Hispanic Blacks and the elderly to allow for more precise estimates in these subgroups. NHANES sample weights were calculated to represent the non-institutionalized general US population and to account for non-coverage and non-response. The National Center for Health Statistics received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and documented consent was obtained from participants in NHANES III. We used NHANES III public use data for this analysis.

Measurement and classification of periodontal disease and edentulism

Participants aged ≥13 years were eligible for the NHANES III clinical dental examination if they had at least one natural tooth and did not have any heart problems or other conditions that require antibiotics before a dental examination. A dentist performed the standardized dental examination and measured periodontal health around the teeth of one upper quadrant and one lower quadrant randomly selected at the beginning of each examination. The distance from the free gingival margin to the bottom of the sulcus and the distance from the free gingival margin to the cemento-enamel junction were recorded at the mesio-facial and mid-facial aspects of each tooth. Periodontal attachment loss was computed from the above measurements to represent the distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the bottom of the sulcus.

For analysis, we classified participants with respect to periodontal disease using two definitions: NHANES and the Centers for Disease Control/American Academy of Periodontology (CDC/AAP) definitions. The NHANES definition of periodontal disease, previously used in other studies utilizing NHANES III data11, 12, is the presence (versus absence) of one or more periodontal sites with both an attachment loss (AL) of ≥3 mm and probing depth (PD) of ≥4 mm. In the CDC/AAP definition13, no periodontitis was defined as no evidence of mild, moderate, or severe periodontitis. Mild periodontitis was defined as ≥2 interproximal sites with AL ≥3 mm, and ≥2 interproximal sites with PD ≥4 mm (not on the same tooth) or 1 site with PD ≥5 mm. Moderate periodontitis was defined as ≥2 interproximal sites with AL ≥4 mm (not on the same tooth), or ≥2 interproximal sites with PD ≥5 mm (not on the same tooth). Severe periodontitis was defined as ≥2 interproximal sites with AL ≥6 mm (not on the same tooth), and ≥1 interproximal site with PD ≥5 mm. We used both definitions to allow for comparisons among studies using these definitions and because the definitions capture different aspects and extents of periodontal disease. For both the NHANES and CDC/AAP definitions, edentulism was defined as not having any natural teeth remaining.

Measurement of total cancer mortality

NHANES III participants were followed passively until December 31, 2015 using multiple data sources, including death certificates and probability matching with the National Death Index to ascertain vital status and cause of death14. For total cancer mortality, we included deaths from malignant neoplasms. Site-specific cancer cause of death is not released in the public use dataset.

Measurement of covariates

Information on age, race/ethnicity, education, annual family income, cigarette smoking, type II diabetes mellitus, and health insurance coverage was collected by standardized in-home interview. Body height, body weight, fasting glucose, and glycated hemoglobin were measured during a mobile medical examination center visit. We categorized race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Mexican-American, and the other race/ethnicity. Attained education was categorized as less than high school, high school, and above high school. Annual family income was categorized as <$25,000, $25,000-$74,999, and >$74,999. Cigarette smoking was categorized as never (men who smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes during their lifetime), former (men who smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and reported that they now smoke “not at all”), and current smokers (men who smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and reported they now smoke “every day” or “some days”). Number of pack years was calculated from smoking duration and number of cigarettes smoked per day for former smokers and current smokers. Health insurance coverage was categorized as covered and not covered. We categorized diabetes status as non-diabetic (no physician diagnosis of diabetes), pre-diabetic (no physician diagnosis of diabetes, and fasting glucose between 100 and 125 mg/dL or glycated hemoglobin between 5.7 and 6.4%), and diabetic (physician diagnosis of diabetes, or fasting glucose >125 mg/dL, or glycated hemoglobin >6.4%). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height (kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

A total of 17,147 participants had the dental examination, and either had periodontal health assessed or were edentulous. We excluded 8,883 participants <40 years old because they have a low risk of cancer (only 1 person with edentulism and 3 people with severe PD died of cancer among those who were aged 18–40 years), and to reduce the likelihood of residual confounding by age and by birth cohort-related secular trends in periodontal disease, edentulism, and cancer. However, in a sensitivity analysis, we ran the analysis beginning follow-up at age 18. We also excluded 915 participants with prior cancer diagnosis, 179 participants with extreme BMI (<18.5 or >50 kg/m2) and 1,136 participants with missing characteristics (height, weight, income, education, cigarette smoking, pack years, diabetes status, and health insurance coverage). Thus, 6,034 participants were included in the analysis.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of the analytic population. NHANES III computed person-time of follow-up for each participant from the date of the baseline examination and questionnaire to the date of cancer death, or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2015), whichever came first. To evaluate the association of periodontal disease and edentulism with cancer mortality, we used Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of cancer mortality. We used age at NHANES III examination as the time scale. The reference group was participants without either periodontal disease per NHANES (or the CDC/AAP) definition or edentulism. In Model 1, we adjusted for age in years (continuous), sex (male, female), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Mexican-American, other race/ethnicity), in Model 2 we further adjusted for BMI (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current), pack-years (continuous), and diabetes (non-diabetic, pre-diabetic, diabetic), and in Model 3 we further adjusted for education (<high school, high school, >high school), annual family income (<$25000, $25000-$74999, >$74999), and health insurance (covered and not covered). We repeated these analyses separately among non-diabetics, and stratified by sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Mexican-American), BMI (normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight/obese ≥25 kg/m2), cigarette smoking history (ever, never), and median age (age <54.8 y, age ≥54.8 y). We tested for interaction using the Wald test. The Cox proportional hazards models all satisfied the proportionality of hazards assumption. All statistical analyses were survey weighted and performed with Stata version 14 (Stata Corp., TX, USA). Statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Data availability

We used data from participants in NHANES III, conducted from 1988–1994, and is available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes3/Default.aspx10. NHANES III participants were followed passively until December 31, 2015 for mortality data using multiple data sources, including death certificates and probability matching with the National Death Index to ascertain vital status and cause of death14. The data we used are publicly available; the analytic datasets used for the analyses will be made available upon reasonable request.

Results

Characteristics of the 6,034 participants are presented in Table 1 for the NHANES definition, and Supplement Table 1 for the CDC/AAP definition of periodontal disease, overall and by periodontal disease and edentulism. The weighted prevalences of periodontal disease and edentulism were 15% and 17%, respectively. Participants with periodontal disease were more likely to be older, male, non-Hispanic Black or Mexican-American, uncovered by health insurance, less educated, a former/current smoker with higher pack-years smoked, and pre-diabetic/diabetic, regardless of the definition used. They were also more likely to have lower annual family income. Participants with edentulism were more likely to be older, female, non-Hispanic White, covered by health insurance, less educated, a former/current smoker with higher pack-years smoked, and pre-diabetic/diabetic, regardless of the definition used. They were also more likely to have a lower annual family income.

Table 1.

Weighted Characteristics of Participants Overall and across NHANES Definitions of Periodontal Disease and Edentulism, 6,034 Participants ≥40 Years Old in NHANES IIIa

| Overall (n=6,034) | No Periodontal Disease (n=3,735) | Periodontal Disease (n=1,147) | Edentulism (n=1,152) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 56.7 (12.5) | 54.5 (11.2) | 56.0 (12.6) | 66.1 (12.7) |

| Male (%) | 48.4 | 46.6 | 61.5 | 44.2 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.4 (5.1) | 27.3 (4.8) | 27.7 (5.5) | 27.7 (5.8) |

| Race (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 80.1 | 81.3 | 70.2 | 84.1 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 10.1 | 8.5 | 17.3 | 10.0 |

| Mexican-American | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 1.4 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 6.4 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 4.60 |

| Health insurance (%) | ||||

| Covered | 96.8 | 96.9 | 95.5 | 97.5 |

| Education (%) | ||||

| <High school | 14.3 | 9.4 | 15.0 | 33.5 |

| High school | 46.4 | 43.7 | 51.8 | 52.4 |

| >High school | 39.4 | 47.0 | 33.2 | 14.1 |

| Income (%), dollars | ||||

| <16,000 | 20.0 | 14.3 | 23.2 | 40.2 |

| 16,000–39,999 | 35.6 | 34.7 | 37.9 | 37.1 |

| >39,999 | 44.4 | 51.0 | 38.9 | 22.7 |

| Pack-years, mean (SD) | 15.0 (24.8) | 11.5 (20.0) | 19.1 (28.3) | 25.2 (36.4) |

| Cigarette smoking status (%) | ||||

| Never | 44.8 | 50.6 | 31.3 | 33.6 |

| Former | 33.5 | 32.0 | 34.3 | 38.9 |

| Current | 21.7 | 17.5 | 34.4 | 27.5 |

| Diabetes (%) | ||||

| No diabetes | 53.3 | 57.6 | 49.7 | 39.2 |

| Pre-diabetes | 34.0 | 32.2 | 35.6 | 40.0 |

| Diabetes | 12.7 | 10.3 | 14.7 | 20.8 |

SD = standard deviation

Assessed one upper quadrant and one lower quadrant. One or more periodontal sites with both an attachment loss of ≥3 mm and probing depth of ≥4 mm

NHANES definition

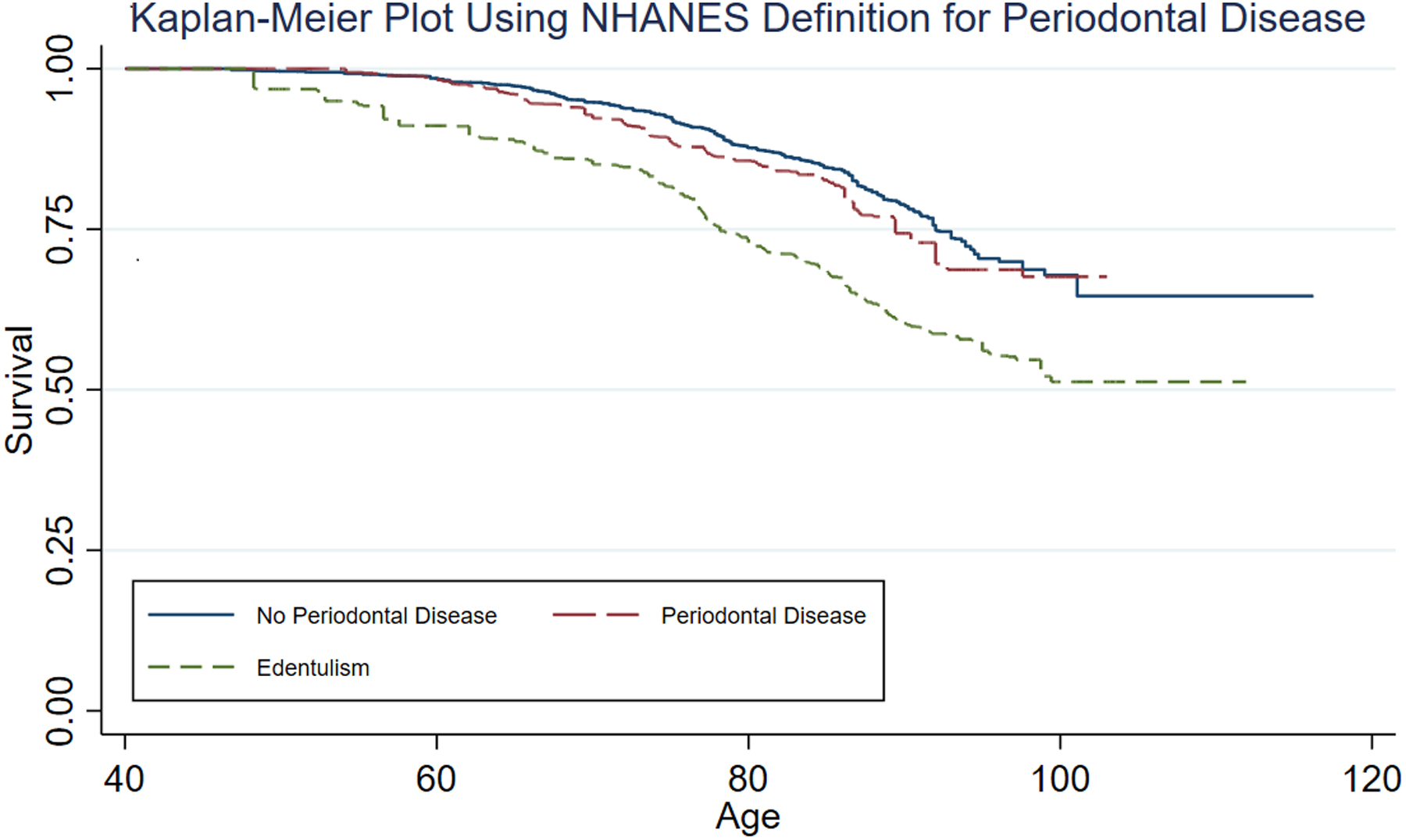

Using the NHANES definition, the Kaplan-Meier estimated crude cumulative risks of cancer mortality from baseline through 2015 were (Figure 1): 35.4% in dentate participants without periodontal disease, 32.4% in participants with periodontal disease, and 48.8% in participants with edentulism. Periodontal disease was not significantly associated with cancer mortality compared to no periodontal disease/dentate overall (Models 1 – 3; Table 2), in subgroups stratified by sex (Table 2), race/ethnicity (Table 3), BMI (Supplement Table 2), median age (data not shown), or in participants without diabetes (Supplement Table 3). Periodontal disease was not associated with cancer mortality in ever cigarette smokers, but we could not rule out an association in never smokers (Supplement Table 4).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Plot Using NHANES Definition for Periodontal Disease

Table 2.

Overall and Sex-Specific Association of Periodontal Disease and Edentulism with Total Cancer Mortality, 6,034 Participants ≥40 Years Old in NHANES IIIa

| Sex specifice | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Males | Females | |||||||

| Cases | Person-years | HR (95% CI) | Cases | Person-years | HR (95% CI) | Cases | Person-years | HR (95% CI) | |

| Periodontitis (NHANES) | |||||||||

| No | 353 | 70847 | 1 (ref) | 189 | 30972 | 1 (ref) | 164 | 39874 | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 151 | 20534 | 1.17 (0.85, 1.62) | 113 | 12071 | 1.24 (0.91, 1.69) | 38 | 8462 | 1.13 (0.55, 2.32) |

| Edentulism | 198 | 14537 | 1.96 (1.45, 2.65) | 118 | 5718 | 2.38 (1.59, 3.56) | 80 | 8819 | 1.64 (1.08, 2.47) |

| Periodontitis (CDC/AAP) | |||||||||

| No | 318 | 70483 | 1 (ref) | 163 | 30458 | 1 (ref) | 155 | 40026 | 1 (ref) |

| Mild | 17 | 3007 | 1.15 (0.60, 2.20) | 10 | 1579 | 0.69 (0.30, 1.56) | 7 | 1428 | 1.84 (0.61, 5.53) |

| Moderate | 133 | 14591 | 1.29 (0.89, 1.87) | 99 | 8738 | 1.29 (0.91, 1.84) | 34 | 5853 | 1.35 (0.63, 2.92) |

| Severe | 36 | 3299 | 1.72 (0.88, 3.35) | 30 | 2269 | 1.96 (0.89, 4.32) | 6 | 1030 | 1.14 (0.41, 3.16) |

| P-trend | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.39 | ||||||

| Edentulism | 198 | 14537 | 2.04 (1.49, 2.80) | 118 | 5718 | 2.46 (1.59, 3.81) | 80 | 8819 | 1.72 (1.11, 2.66) |

| Model 2c | |||||||||

| Periodontitis (NHANES) | |||||||||

| No | 353 | 70847 | 1 (ref) | 189 | 30972 | 1 (ref) | 164 | 39874 | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 151 | 20534 | 1.00 (0.73, 1.37) | 113 | 12071 | 1.07 (0.79, 1.43) | 38 | 8462 | 0.94 (0.47, 1.88) |

| Edentulism | 198 | 14537 | 1.58 (1.19, 2.09) | 118 | 5718 | 1.89 (1.25, 2.84) | 80 | 8819 | 1.34 (0.90, 2.01) |

| Periodontitis (CDC/AAP) | |||||||||

| No | 318 | 70483 | 1 (ref) | 163 | 30458 | 1 (ref) | 155 | 40026 | 1 (ref) |

| Mild | 17 | 3007 | 1.10 (0.59, 2.03) | 10 | 1579 | 0.69 (0.31, 1.55) | 7 | 1428 | 1.67 (0.60, 4.65) |

| Moderate | 133 | 14591 | 1.02 (0.70, 1.48) | 99 | 8738 | 1.05 (0.73, 1.50) | 34 | 5853 | 1.07 (0.49, 2.31) |

| Severe | 36 | 3299 | 1.23 (0.62, 2.45) | 30 | 2269 | 1.42 (0.63, 3.20) | 6 | 1030 | 0.75 (0.28, 2.01) |

| P-trend | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Edentulism | 198 | 14537 | 1.61 (1.20, 2.16) | 118 | 5718 | 1.92 (1.22, 3.01) | 80 | 8819 | 1.39 (0.92, 2.10) |

| Model 3d | |||||||||

| Periodontitis (NHANES) | |||||||||

| No | 353 | 70847 | 1 (ref) | 189 | 30972 | 1 (ref) | 164 | 39874 | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 151 | 20534 | 0.99 (0.72, 1.36) | 113 | 12071 | 1.02 (0.75, 1.38) | 38 | 8462 | 0.95 (0.48, 1.87) |

| Edentulism | 198 | 14537 | 1.50 (1.12, 2,00) | 118 | 5718 | 1.62 (1.05, 2.48) | 80 | 8819 | 1.43 (0.92, 2.22) |

| Periodontitis (CDC/AAP) | |||||||||

| No | 318 | 70483 | 1 (ref) | 163 | 30458 | 1 (ref) | 155 | 40026 | 1 (ref) |

| Mild | 17 | 3007 | 1.06 (0.56, 1.99) | 10 | 1579 | 0.60 (0.27, 1.33) | 7 | 1428 | 1.69 (0.63, 4.51) |

| Moderate | 133 | 14591 | 1.00 (0.68, 1.46) | 99 | 8738 | 1.02 (0.72, 1.44) | 34 | 5853 | 1.11 (0.49, 2.50) |

| Severe | 36 | 3299 | 1.20 (0.60, 2.38) | 30 | 2269 | 1.32 (0.57, 3.06) | 6 | 1030 | 0.79 (0.29, 2.16) |

| P-trend | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.92 | ||||||

| Edentulism | 198 | 14537 | 1.52 (1.12, 2.07) | 118 | 5718 | 1.63 (1.01, 2.61) | 80 | 8819 | 1.49 (0.94, 2.37) |

HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, CDC/AAP = Centers for Disease Control/American Academy of Periodontology

Model 1 adjusted for age in years (continuous), sex (males and females), and race/ethnicity (Nnon-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White, Mexican-American, other race/ethnicity).

Model 2 adjusted for age in years (continuous), sex (males and females), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White, Mexican-American, other race/ethnicity), body mass index (continuous), pack years (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current), and diabetes (non-diabetic, pre-diabetic, diabetic).

Model 3 adjusted for age in years (continuous), sex (males and females), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White, Mexican-American, other race/ethnicity), body mass index (continuous), pack years (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current), diabetes (non-diabetic, pre-diabetic, diabetic), education (<high school, high school, >high school), annual family income (<$25000, $25000-$74999, >$74999), and health insurance (covered and not covered).

For analysis stratified by sex, none of the three models adjusted for sex.

Table 3.

Race/Ethnicity-Specific Association of Periodontal Disease and Edentulism with Total Cancer Mortality, 6,034 Participants ≥40 Years Old in NHANES IIIa

| Race specific | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Mexican-American | |||||||

| Cases | Person-years | HR (95% CI) | Cases | Person-years | HR (95% CI) | Cases | Person-years | HR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1b | |||||||||

| Periodontitis (NHANES) | |||||||||

| No | 174 | 33497 | 1 (ref) | 93 | 16661 | 1 (ref) | 78 | 17633 | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 43 | 6498 | 1.08 (0.72, 1.64) | 60 | 7643 | 1.26 (0.85, 1.86) | 44 | 5467 | 1.45 (0.97, 2.18) |

| Edentulism | 112 | 8255 | 1.87 (1.34, 2.61) | 54 | 4047 | 1.83 (1.20, 2.78) | 27 | 1706 | 2.04 (1.00, 4.19) |

| Periodontitis (CDC/AAP) | |||||||||

| No | 163 | 33037 | 1 (ref) | 79 | 17064 | 1 (ref) | 68 | 17289 | 1 (ref) |

| Mild | 6 | 1009 | 0.86 (0.38, 1.95) | 5 | 1192 | 0.75 (0.34, 1.63) | 3 | 637 | 0.74 (0.18, 3.06) |

| Moderate | 39 | 5053 | 1.23 (0.76, 1.98) | 50 | 4693 | 1.62 (1.08, 2.44) | 43 | 4315 | 1.82 (1.19, 2.80) |

| Severe | 9 | 896 | 1.96 (0.77, 4.99) | 19 | 1355 | 2.40 (1.20, 4.81) | 8 | 858 | 1.48 (0.54, 4.06) |

| P-trend | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Edentulism | 112 | 8255 | 1.94 (1.39, 2.71) | 54 | 4047 | 2.09 (1.29, 3.40) | 27 | 1706 | 2.30 (1.07, 4.96) |

| Model 2c | |||||||||

| Periodontitis (NHANES) | |||||||||

| No | 174 | 33497 | 1 (ref) | 93 | 16661 | 1 (ref) | 78 | 17633 | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 43 | 6498 | 0.93 (0.62, 1.39) | 60 | 7643 | 1.23 (0.82, 1.85) | 44 | 5467 | 1.34 (0.85, 2.11) |

| Edentulism | 112 | 8255 | 1.50 (1.09, 2.05) | 54 | 4047 | 1.60 (1.05, 2.43) | 27 | 1706 | 1.96 (0.99, 3.88) |

| Periodontitis (CDC/AAP) | |||||||||

| No | 163 | 33037 | 1 (ref) | 79 | 17064 | 1 (ref) | 68 | 17289 | 1 (ref) |

| Mild | 6 | 1009 | 0.84 (0.37, 1.90) | 5 | 1192 | 0.79 (0.37, 1.70) | 3 | 637 | 0.72 (0.18, 2.81) |

| Moderate | 39 | 5053 | 0.96 (0.59, 1.54) | 50 | 4693 | 1.39 (0.92, 2.11) | 43 | 4315 | 1.67 (1.00, 2.79) |

| Severe | 9 | 896 | 1.40 (0.53, 3.68) | 19 | 1355 | 1.97 (0.93, 4.15) | 8 | 858 | 1.30 (0.37, 4.55) |

| P-trend | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.13 | ||||||

| Edentulism | 112 | 8255 | 1.52 (1.11, 2.09) | 54 | 4047 | 1.74 (1.06, 2.86) | 27 | 1706 | 2.16 (1.02, 4.59) |

| Model 3d | |||||||||

| Periodontitis (NHANES) | |||||||||

| No | 174 | 33497 | 1 (ref) | 93 | 16661 | 1 (ref) | 78 | 17633 | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 43 | 6498 | 0.94 (0.62, 1.40) | 60 | 7643 | 1.20 (0.81, 1.80) | 44 | 5467 | 1.23 (0.79, 1.94) |

| Edentulism | 112 | 8255 | 1.51 (1.08, 2.13) | 54 | 4047 | 1.53 (1.00, 2.33) | 27 | 1706 | 1.90 (0.91, 3.98) |

| Periodontitis (CDC/AAP) | |||||||||

| No | 163 | 33037 | 1 (ref) | 79 | 17064 | 1 (ref) | 68 | 17289 | 1 (ref) |

| Mild | 6 | 1009 | 0.83 (0.35, 1.94) | 5 | 1192 | 0.71 (0.32, 1.59) | 3 | 637 | 0.71 (0.10, 2.65) |

| Moderate | 39 | 5053 | 0.95 (0.58, 1.57) | 50 | 4693 | 1.40 (0.94, 2.10) | 43 | 4315 | 1.48 (0.84, 2.62) |

| Severe | 9 | 896 | 1.41 (0.52, 3.87) | 19 | 1355 | 1.92 (0.92, 3.98) | 8 | 858 | 1.12 (0.33, 3.78) |

| P-trend | 0.71 | 0.11 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Edentulism | 112 | 8255 | 1.54 (1.08, 2.19) | 54 | 4047 | 1.68 (1.03, 2.74) | 27 | 1706 | 2.04 (0.90, 4.64) |

HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, CDC/AAP = Centers for Disease Control/American Academy of Periodontology

Model 1 adjusted for age in years (continuous), and sex (males and females).

Model 2 adjusted for age in years (continuous), sex (males and females), body mass index (continuous), pack years (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current), and diabetes (non-diabetic, pre-diabetic, diabetic).

Model 3 adjusted for age in years (continuous), sex (males and females), body mass index (continuous), pack years (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current), diabetes (non-diabetic, pre-diabetic, diabetic), education (<high school, high school, >high school), annual family income (<$25000, $25000-$74999, >$74999), and health insurance (covered and not covered).

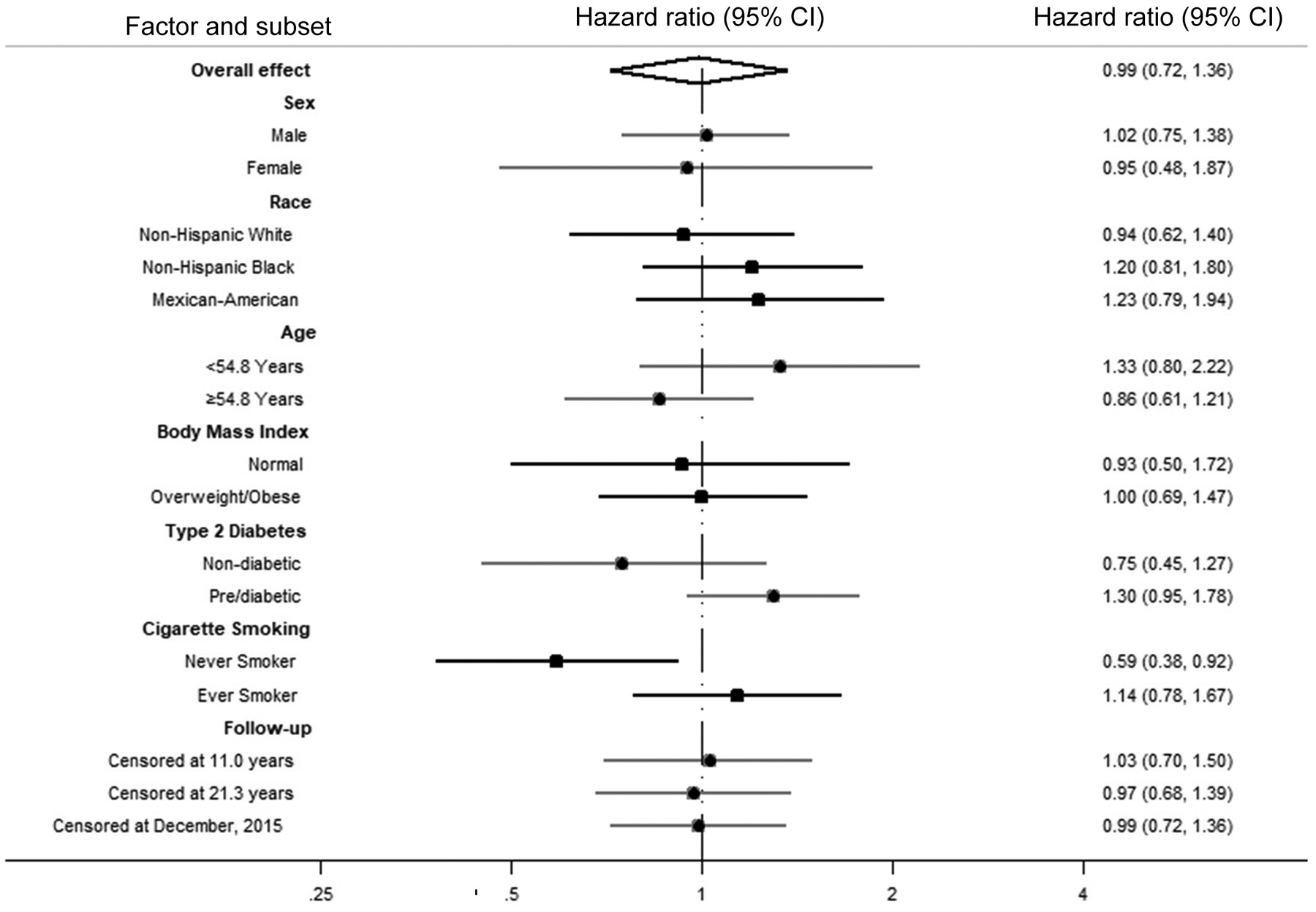

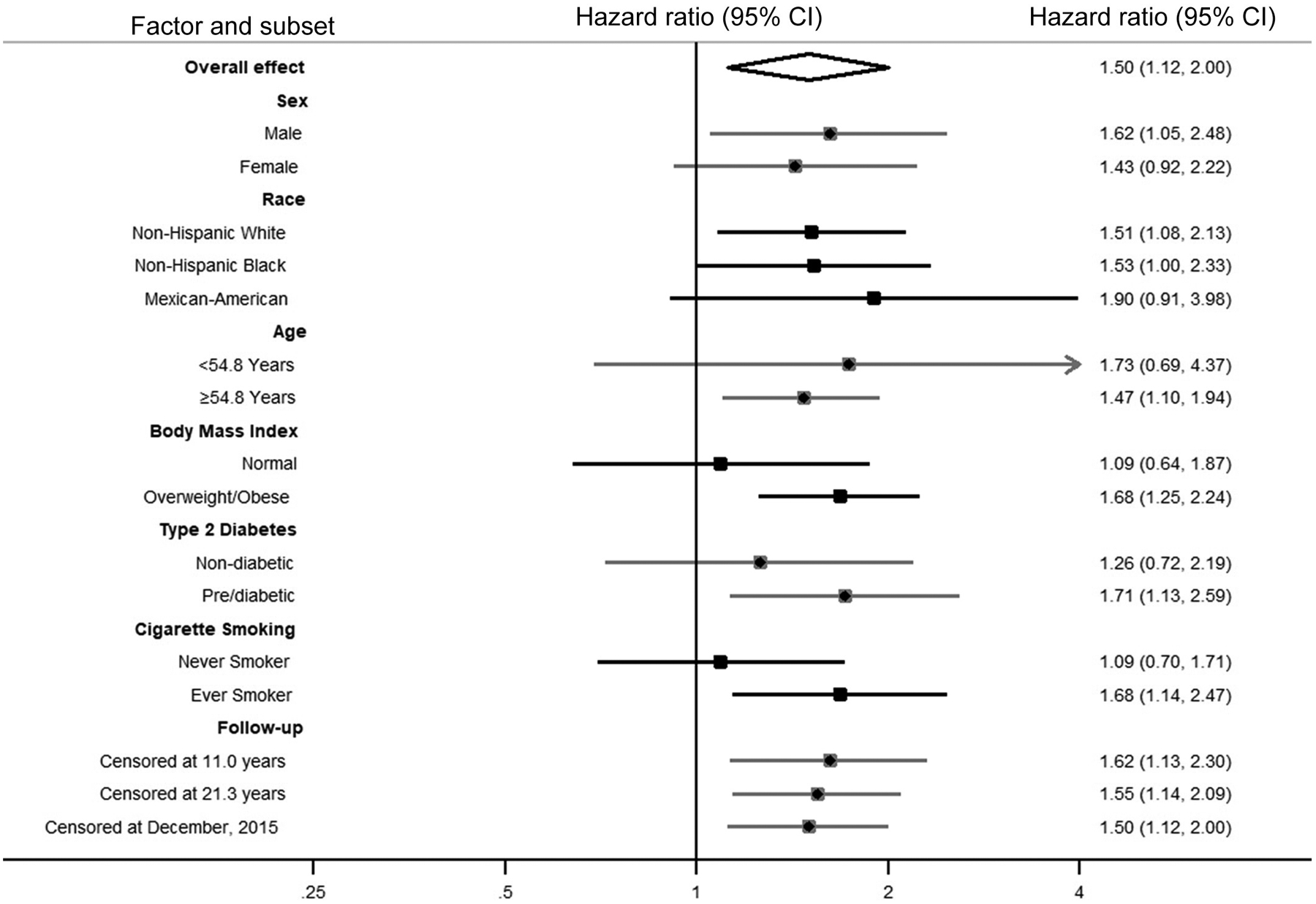

Compared with no periodontal disease/dentate, edentulism was associated with an increased risk of cancer mortality, including after adjustment for demographics, lifestyle factors, and education, annual family income, and health insurance coverage (Model 3: HR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.12 to 2.00; Table 2). The positive association between edentulism and cancer mortality was apparent in men (Model 3: HR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.05 to 2.48) and women (Model 3: HR = 1.43, 95% CI = 0.92 to 2.22; P -interaction = 0.19; Table 2), in non-Hispanic White (Model 3: HR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.08 to 2.13; Table 3), non-Hispanic Black (Model 3: HR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.00 to 2.33; Table 3), and in Mexican-American (Model 3: HR = 1.90, 95% CI = 0.91 to 3.98; P-interaction = 0.58; Table 3) participants, and in younger and older participants (data not shown). There was no difference when stratifying by median age (data not shown). The positive association between edentulism and cancer mortality was observed in overweight/obese participants but not participants with normal BMI (Supplement Table 2; P-interaction = 0.66), in pre/diabetic participants but possibly only weakly in participants without diabetes (Supplement Table 3; P-interaction = 0.07), and in ever cigarette smokers but not never cigarette smokers (Supplement Table 4; P-interaction = 0.059). Figure 2 and 3 show the forest plots of association of periodontal disease and edentulism with total cancer mortality overall and by subgroups.

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of Overall and Stratum-Specific Hazard Ratios of Total Cancer Mortality Comparing No Periodontal Disease to Periodontal Disease

Figure 3.

Forest Plot of Overall and Stratum-Specific Hazard Ratios of Total Cancer Mortality Comparing Edentulism to Periodontal Disease

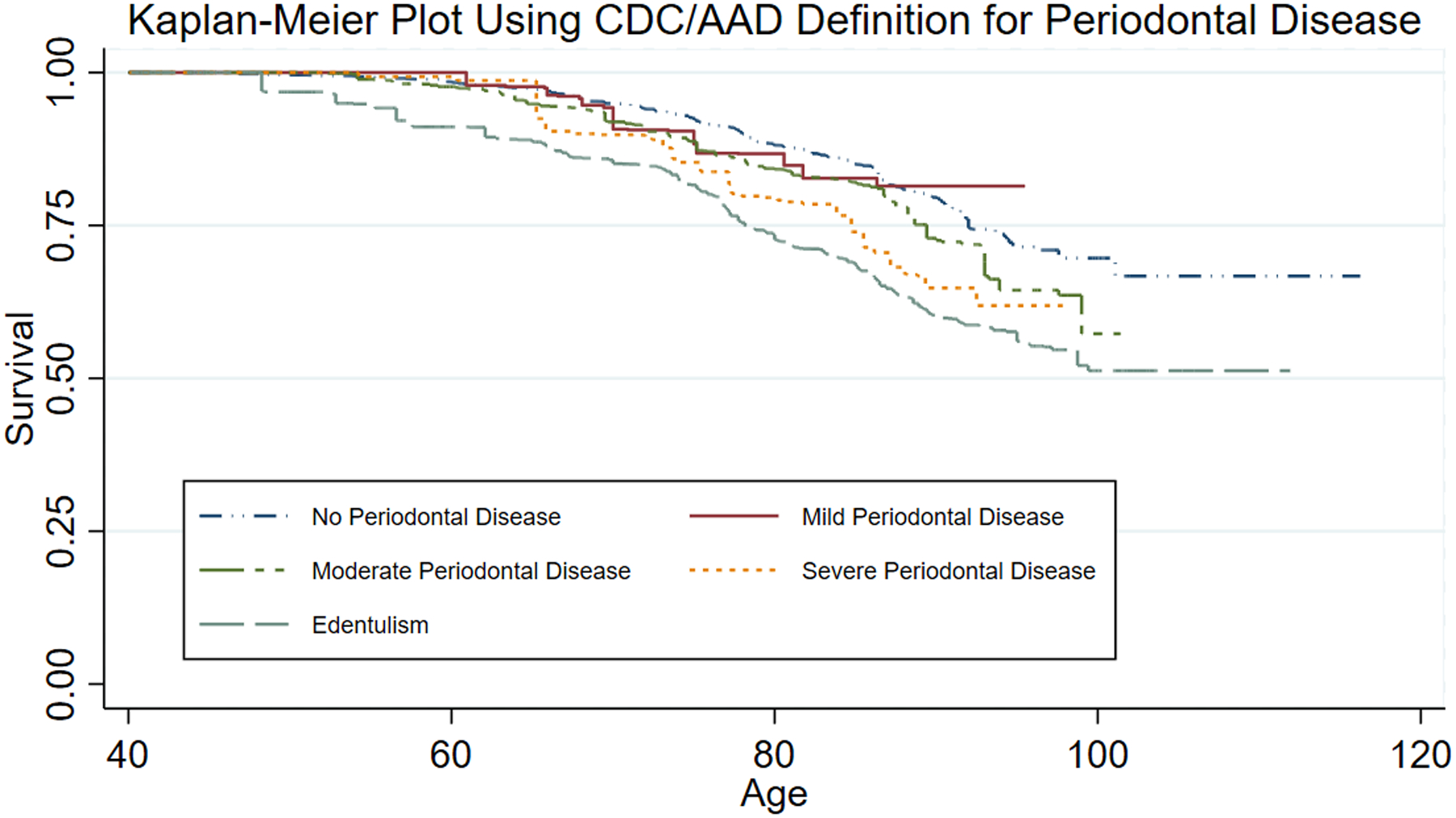

CDC/AAP definition

Using the CDC/AAP definition, the Kaplan-Meier estimated crude cumulative risks of cancer mortality from baseline through 2015 were (Figure 4): 33.3% in dentate participants with no periodontal disease, 18.6% in participants with mild periodontal disease, 42.3% in participants with moderate periodontal disease, 38.1% in participants with severe periodontal disease, and 48.8% in participants with edentulism. Periodontal disease was not significantly associated with cancer mortality compared to no periodontal disease/dentate overall (Models 1 – 3; Table 2), in subgroups stratified by sex (Table 2), race/ethnicity (Table 3), BMI (Supplement Table 2), median age (data not shown), in participants without diabetes (Supplement Table 3), or in never smokers (Supplement Table 4). The positive associations for edentulism observed using the NHANES definition were also observed when using the CDC/AAP definition and comparing to no periodontal disease/dentate (overall, Table 2; in men and women, Table 2, P-interaction = 0.32; in each racial/ethnic, Table 3, P-interaction =0.50; in overweight/obese participants, Supplement Table 2, P-interaction = 0.30; in pre/diabetic participants, Supplement Table 3, P-interaction = 0.049; in ever cigarette smokers, Supplement Table 4, P-interaction = 0.72; in each age group, data not shown).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier Plot Using CDC/AAP Definition for Periodontal Disease

Sensitivity analysis

When censoring follow-up at 11.0 years or at the median of 21.3 years, the patterns of association for periodontal disease (null) and edentulism (positive) remained (Supplement Table 5). When starting follow-up at age 18, the HRs for periodontal disease defined by NHANES definition (HR=1.09, 95% CI = 0.83 to 1.44) and edentulism (HR=1.53, 95% CI = 1.15 to 2.04) were slightly higher than in the main analysis (Supplement Table 6). Similarly, the HRs for severe periodontal disease defined by CDC/AAP definition (HR=1.49, 95% CI = 0.77 to 2.89; P-trend = 0.27) and edentulism (HR=1.58, 95% CI = 1.17 to 2.14) were slightly higher than in the main analysis (Supplement Table 6). When using the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) definition as done previously in Michaud et al.3, results were comparable to the main analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted on periodontal disease, edentulism, and total cancer mortality adjusting for social factors and shared risk factors for cancer and periodontal disease that used a standardized clinical dental examination in a nationally representative population. We observed an increased risk of total cancer mortality in participants with edentulism, but not periodontal disease, at baseline compared to those without periodontal disease and were dentate. Associations for edentulism were stronger in participants with shared risk factors for periodontal disease and cancer – those who were overweight/obese, pre/diabetic, and ever cigarette smokers, suggesting that these factors interact to increase risk of cancer mortality. Edentulism was associated with cancer mortality in non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Mexican-American participants, participants in the 40–54.8 age range, and participants ≥54.8 years old.

Previous studies have investigated the association between periodontal disease and cancer incidence and mortality. The increase risk of total cancer incidence associated with periodontal disease ranged between 14% and 24% in four prospective studies controlling for smoking, despite substantial differences in periodontal disease assessment and study populations3, 5, 15, 16. In the ARIC cohort, Michaud et al. reported a non-statistically significant positive association using the CDC-AAP definition between periodontal disease severity and total cancer mortality (P-trend = 0.07) and an increased risk of total cancer death for those with edentulism (HR = 1.49, 95% CI = 1.12 to 1.99), compared to those with no periodontitis and were dentate3. However, when using the ARIC definition, both severe periodontal disease and edentulism were statistically significantly positively associated with cancer mortality3. In the current NHANES III study, we adjusted for a similar array of shared risk factors for cancer and periodontal disease, including smoking and social factors. The findings for periodontal disease, edentulism and cancer mortality in the current NHANES analysis are consistent with those from ARIC when using the CDC/AAP definitions. However, our observation of a positive association between edentulism and total cancer mortality in non-Hispanic Black participants using both the NHANES and CDC/AAP definitions differs from the null association in Black participants in ARIC using the CDC/AAP definitions. The discrepancy remained even when both of NAHENS study and the ARIC study used ARIC definition for periodontal disease.

Both Michaud et al.3 and the current study each used two definitions of periodontal disease (ARIC study: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American Academy of Periodontology [CDC/AAP] and ARIC definitions; NHANES study: NHANES and CDC/AAP definitions). We used two definitions to allow for comparisons among studies using these definitions (e.g., compare the current study with Michaud et al. when using the CDC/AAP definition) and because the definitions capture different aspects and extents of periodontal disease. We observed some subtle differences in associations between the definitions. For example, in NHANES III in non-Hispanic Black participants, association for edentulism (HR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.74) using the CDC/AAP definition for no periodontal disease in those who are dentate as the comparison group appeared to be slightly stronger than edentulism (HR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.00 to 2.33) using the NHANES definition for no periodontal disease in those who are dentate as the comparison group. Observing such possible differences highlights the need to better understand how different definitions reflect underlying true periodontal health and biological mechanisms, and their associations with unmeasured confounders or different extents of residual confounding by known risk factors.

A subset of the NHANES III data with follow-up through 2006 that we used were used previously to investigate the association between periodontal disease and orodigestive cancer mortality17, finding a twofold increased risk among those with moderate (RR = 2.22, 95% CI = 1.11 to 4.46) and aggressive periodontitis (RR = 2.64, 95% CI = 0.85 to 8.23; P-trend = 0.01), compared with those with no periodontitis17; edentulism was not studied. Because the public use data for follow-up through 2015 that we used does not provide site specific cancer cause of death and because NHANES does not conduct active follow-up for incidence, we could not investigate with longer follow-up the prior NHANES finding on orodigestive cancer mortality, or the previously observed positive associations for periodontal disease and risks of pancreatic and lung cancers3, 7, 18, 19 or the less consistent possible associations for breast, colorectal, other cancers3, 7, 20–22 found in other studies.

Because of the richness of the NHANES III data, we were able to adjust for cancer risk factors that are also risk factors for periodontal disease and edentulism, including smoking, obesity, and diabetes. While the associations for edentulism were substantially attenuated when adjusting for these factors, they nevertheless persisted. Because of concerns about confounding by social factors including education, income, and health insurance coverage, we additionally adjusted for these, and observed only modest attenuation of the association for edentulism. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out residual confounding by these factors.

We observed possibly stronger associations for edentulism in men than in women, and associations that were largely restricted to those with shared risk factors for periodontal disease and cancer, including in those who are overweight/obese, pre/diabetic, or ever cigarette smokers. At least three explanations for these findings are possible. First, because we studied total cancer mortality, it is possible that these differences are due, at least in part, to different compositions of site-specific cancer deaths in those subgroups. For example for sex, in the ARIC study, Michaud et al. found that edentulism was associated with total cancer incidence and mortality only in men, and for incidence noted that the edentulism association for colorectal cancer was similar in men and women, but that the edentulism association for lung cancer was substantially stronger in men3. These observations suggest that different proportions of cancer sites in men in women could explain some of the difference in strength of the association between edentulism and total cancer by sex. Second, these stratum-specific differences may also be explained by biological interaction between the factors that lead to edentulism and the shared risk factors. Third, the number of events tended to be larger among those with the shared risk factors, increasing the ability to detect associations with precision. In those without shared risk factors, associations tended to be null or less consistent; for example, in never smokers, periodontal disease using the NHANES definition was inversely associated while severe periodontal disease using the CDC/AAP was not associated with cancer mortality.

Although periodontal disease was measured clinically and we used two definitions to define periodontal disease, these may still be imperfect. The NHANES III dental examination did not measure the periodontal health of all teeth, only one upper and one lower quadrant, and thus both the NHANES and CDC/AAP definitions may not have identified all participants who truly had periodontal disease, the effect of which would be to underestimate any positive association. More recent NHANES cycles assessed all teeth9, and report a higher age-specific prevalence of periodontal disease than NHANES III. We did not use the more recent NHANES cycles because the follow-up time is relatively short for cancer. In addition, we treated periodontal disease and edentulism as fixed exposure due to the design of NHANES III (cross-sectional) linked with mortality passive follow-up. Periodontal disease status or severity and edentulism could have changed during the long follow-up time, given that the dental examination predated cancer diagnosis by a median of 21.3 years. We expect that this possible source of misclassification of periodontal disease and edentulism could attenuate their associations with cancer death toward the null, which could account for the null associations that we observed for periodontal disease. We attempted to reduce that bias by excluding those who were eligible for and had the dental examination who were 13 to 40 years old. In one sensitivity analysis, we ended follow-up earlier and still noted a positive association for edentulism, but no association for periodontal disease. In another sensitivity analysis, we started follow-up at age 18. The slightly higher HRs for periodontal disease and edentulism as compared to the main analysis may due to residual confounding by age.

We studied edentulism as a common consequence or treatment for severe periodontal disease, and by doing so, assumed that edentulism marks biological pathways underlying periodontitis that are also etiologically relevant for carcinogenesis. However, edentulism can result from other reasons8. Thus, it is possible that the positive association between edentulism and cancer mortality, may be due to factors unrelated to periodontal disease. However, despite adjusting for numerous lifestyle and social factors, we cannot rule out residual confounding of the overall association between edentulism and cancer mortality by the factors we adjusted for or by unmeasured confounders. We took into account modifiable cancer risk factors that are also risk factors for periodontal disease and edentulism by both adjustment and stratification. Associations tended to be stronger in those with the shared risk factors, suggesting their interaction. We attempted to take into account social factors by adjusting for education, family income, and health insurance coverage. These social factors were assessed at the time of the dental examination and may not capture earlier life social factors and their correlates that may be linked with both edentulism and cancer.

Strengths of this study include the prospective design, the approximate 20-year follow-up since the dental examination, and the completeness of passive follow-up for cancer death. In addition, we studied a US nationally representative sample, increasing the likelihood that the findings are generalizable. We used data to classify periodontal disease from a standard dental examination performed by licensed dentists specially trained in the use of specific epidemiologic indices for oral health, reducing measurement error as compared to self-reported periodontal disease. The dental examination was performed as part of the NHANES protocol and not based on access to care, reducing selection bias.

In summary, in this US nationally representative population aged 40 and older, participants with edentulism, but not periodontal disease, had a higher risk of cancer death, especially in those with shared risk factors for periodontal disease and cancer. This study supports the growing literature on the importance of dental health for cancer prevention and control and suggests the need for investigation of the mechanisms underlying these associations we and others have observed.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Impact:

This is the first study conducted on periodontal disease, edentulism, and total cancer mortality adjusting for social factors and shared risk factors for cancer and periodontal disease that used a standardized clinical dental examination in a nationally representative population. Participants with edentulism, but not periodontal disease, had a higher risk of cancer death even after taking into account demographics, shared risk factors, and social factors in the US nationally representative population aged 40 and older.

Funding:

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (P30CA006973, Nelson), the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund at Johns Hopkins, and the 2018 AACR-Johnson & Johnson Lung Cancer Innovation Science Grant Number 18-90-52-MICH.

Abbreviations:

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- CDC/AAP

Centers for Disease Control/American Academy of Periodontology

- AL

attachment loss

- PD

probing depth

- BMI

body mass index

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Reference

- 1.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbial etiological agents of destructive periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 1994;5: 78–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, Seymour GJ, Kornman KS. Advances in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: summary of developments, clinical implications and future directions. Periodontology 2000 1997;14: 216–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michaud DS, Lu J, Peacock-Villada AY, Barber JR, Joshu CE, Prizment AE, Beck JD, Offenbacher S, Platz EA. Periodontal Disease Assessed Using Clinical Dental Measurements and Cancer Risk in the ARIC Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2018;110: 843–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajishengallis G Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nature reviews Immunology 2015;15: 30–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaud DS, Liu Y, Meyer M, Giovannucci E, Joshipura K. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and cancer risk in male health professionals: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Oncology 2008;9: 550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen BW, Tsai CS, Lin CL, Chang YJ, Lee CF, Hsu CH, Kao CH. Cancer risk among gingivitis and periodontitis patients: a nationwide cohort study. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians 2014;107: 283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michaud DS, Fu Z, Shi J, Chung M. Periodontal Disease, Tooth Loss, and Cancer Risk. Epidemiologic reviews 2017;39: 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slade GD, Akinkugbe AA, Sanders AE. Projections of U.S. Edentulism prevalence following 5 decades of decline. Journal of dental research 2014;93: 959–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Dye BA, Genco RJ. Periodontitis in US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2014. Journal of the American Dental Association 2018;149: 576–88 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezzati TM, Massey JT, Waksberg J, Chu A, Maurer KR. Sample design: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Vital and health statistics Series 2, Data evaluation and methods research 1992: 1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Borawskit EA. Obesity and periodontal disease in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Journal of periodontology 2003;74: 610–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of periodontology 2000;71: 743–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eke PI, Page RC, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco RJ. Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. Journal of periodontology 2012;83: 1449–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2015 Public-Use Linked Mortality Files.

- 15.Arora M, Weuve J, Fall K, Pedersen NL, Mucci LA. An exploration of shared genetic risk factors between periodontal disease and cancers: a prospective co-twin study. American journal of epidemiology 2010;171: 253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mai X, LaMonte MJ, Hovey KM, Freudenheim JL, Andrews CA, Genco RJ, Wactawski-Wende J. Periodontal disease severity and cancer risk in postmenopausal women: the Buffalo OsteoPerio Study. Cancer causes & control : CCC 2016;27: 217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn J, Segers S, Hayes RB. Periodontal disease, Porphyromonas gingivalis serum antibody levels and orodigestive cancer mortality. Carcinogenesis 2012;33: 1055–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maisonneuve P, Amar S, Lowenfels AB. Periodontal disease, edentulism, and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2017;28: 985–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mai X, LaMonte MJ, Hovey KM, Nwizu N, Freudenheim JL, Tezal M, Scannapieco F, Hyland A, Andrews CA, Genco RJ, Wactawski-Wende J. History of periodontal disease diagnosis and lung cancer incidence in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Cancer causes & control : CCC 2014;25: 1045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi T, Min M, Sun C, Zhang Y, Liang M, Sun Y. Periodontal disease and susceptibility to breast cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of clinical periodontology 2018;45: 1025–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu JM, Shen CJ, Chou YC, Hung CF, Tian YF, You SL, Chen CY, Hsu CH, Hsiao CW, Lin CY, Sun CA. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with periodontal disease severity: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. International journal of colorectal disease 2018;33: 349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Momen-Heravi F, Babic A, Tworoger SS, Zhang L, Wu K, Smith-Warner SA, Ogino S, Chan AT, Meyerhardt J, Giovannucci E, Fuchs C, Cho E, et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and colorectal cancer risk: Results from the Nurses' Health Study. International journal of cancer 2017;140: 646–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We used data from participants in NHANES III, conducted from 1988–1994, and is available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes3/Default.aspx10. NHANES III participants were followed passively until December 31, 2015 for mortality data using multiple data sources, including death certificates and probability matching with the National Death Index to ascertain vital status and cause of death14. The data we used are publicly available; the analytic datasets used for the analyses will be made available upon reasonable request.