Cardiology has long been a male-dominated field. The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and other credentialing organizations estimate that approximately 10% to 14% of board-certified and/or active adult cardiologists in the United States are women (1,2). Over the past 12 years, the proportion of women in U.S. general cardiology fellowship programs has languished at 20% (3). Although the percentage of women in U.S. internal medicine training programs has increased over the last 25 years, with women now comprising more than one-half of all matriculants, the proportion of women training in subspecialty fellowships has decreased. From 1991 to 2016, cardiology attracted the fewest women of 9medical subspecialties and had the lowest rates of increase in enrolled women over this period (4).

The ACC and other societies have taken meaningful steps toward identifying sex disparities in cardiology and encouraging diversity and inclusion (1). Much has been written about barriers to the engagement of women, including wage inequality (5,6); bias, discrimination, and sexual harassment (7); lack of institutional support, mentorship, and role modeling (8); inadequate workplace support for pregnant and nursing cardiologists (9); and negative perceptions of the field (10–12). Fellows-in-training (FITs) and early career cardiologists (ECs) are particularly affected by these barriers at: 1) major career transitions, when cultivating mentorship and sponsorship relationships becomes essential; 2) during childbearing and early parenting years; and 3) because sex biases can adversely influence professional advancement (13,14). Specific action plans that individuals and institutions can implement to highlight and ameliorate these disparities are lacking.

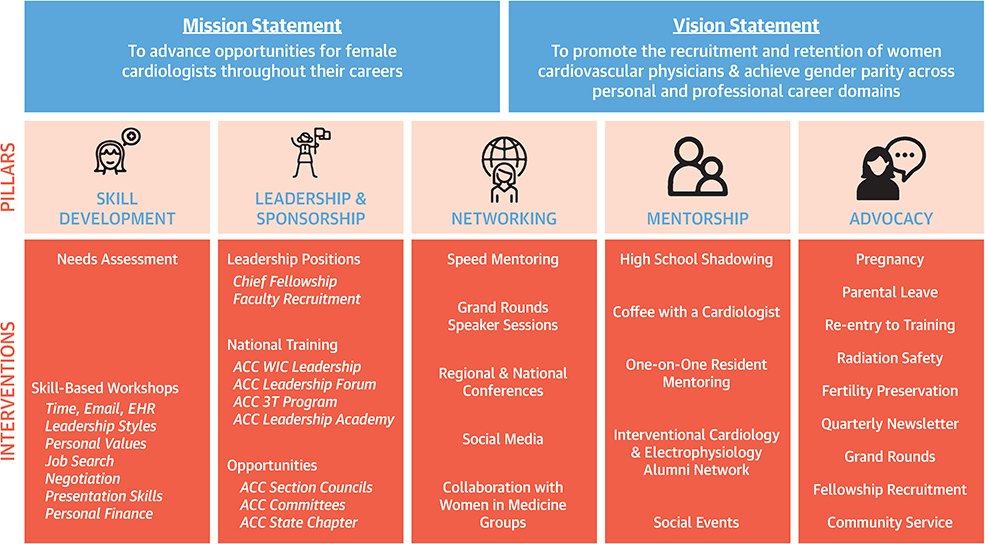

In 2017, we founded the Penn Women in Cardiology (PWIC), an organization of female FITs and faculty established to promote the recruitment, retention, and advancement of female cardiologists. Over the last 3 years, PWIC has implemented goal-oriented programming for all levels of trainees and faculty to directly address barriers faced by women in cardiovascular medicine (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Mission, Vision, and Framework for the Establishment of a Formal Program to Support Women in Cardiology.

Key pillars of this program include skill development, leadership and sponsorship, networking, mentorship, and advocacy. ACC = American College of Cardiology; EHR = electronic health record.

SKILL DEVELOPMENT

We conducted a needs assessment, targeted to female FITs and faculty, from which we identified deficiencies in professional skills as the initial target for intervention. Women from within and outside of our institution subsequently led a dedicated curriculum on these topics. In our Time, Email, and EHR Management workshop, women learned how to assign value to professional projects and responsibilities. In our Leadership Style practicum taught by an expert from the Wharton School of Business, attendees gained insight into their leadership preferences. In our Identifying and Balancing Personal Values seminar, an executive coach guided women through skill building in conflict resolution and negotiation. FITs learned about the fellow-to-faculty transition through our Job Search, Contracts, and Promotions didactic with the division business administrator.

LEADERSHIP AND SPONSORSHIP

We are creating a culture in which mentor and sponsor FITs and ECs for leadership opportunities. Over the last 5 years, 60% of our chief fellows have been women. FITs attend national leadership training conferences with support from the fellowship and share new knowledge with PWIC through formal presentations upon their return. We encourage and nominate FITs to apply for ACC opportunities and have had 3 women serve as FIT Editorial Fellows, 5 on Pennsylvania ACC Chapter task forces, 6 on national ACC leadership councils, 15 as speakers at national conferences, and many in leadership positions in multiple other professional societies.

NETWORKING

Women build, maintain, and utilize professional networks less effectively than men (15). We counteract this with programming focused on developing networks and networking skills. In our Speed Mentoring, FITs are paired with women faculty in a speed dating-style session to hone their “elevator pitches” and exchange perspectives on being good mentees and mentors. Visiting female Grand Rounds speakers regularly meet with PWIC for Special Speaker Sessions; over the last 3 years, we have met with 13 eminent female faculty in cardiovascular medicine. Through these opportunities, FITs and ECs learn about the careers of successful WIC and meet new potential mentors, sponsors, employers, and collaborators.

MENTORSHIP

From PWIC’s inception, we have prioritized outreach to students and residents. In Coffee with a Cardiologist, we pair individual medical students with PWIC members to discuss careers in cardiology. After their initial meetings, medical students shadow FITs and ECs and remain in contact with them. Internal medicine interns considering cardiology have One-on-One Mentoring Meetings in which PWIC members create action plans for the second to third years of residency, outline the fellowship application process, connect trainees with research mentors, and offer experiences for clinical cardiology exposure. These meetings also allow PWIC members to tackle perceived myths about cardiology that may otherwise deter trainees from the field. Three “undecided” women residents have chosen cardiology as a result of PWIC mentorship.

This year, we will launch our interventional cardiology and clinical cardiac electrophysiology (CCEP) Alumni Network. Last year, women comprised only 12% of CCEP and 10% of IC fellows (16). The lack of female role models in interventional cardiology and CCEP strongly deters women from pursuing these careers (17,18). We will use Internet-based platforms for remote mentoring sessions to strengthen the quantity and quality of role modeling for women in procedural specialties.

ADVOCACY

Many female cardiologists face significant workrelated barriers to pre-conception health, pregnancy, and breastfeeding (9). We developed and disseminated Guidelines and Expectations for Breastfeeding Mothers, which summarizes challenges faced by nursing FITs, delineates how each barrier should be addressed in the clinical environment, and offers resources to FITs and supervisors (19). The fellowship program offsets expenses related to childcare and pumping supplies incurred by new trainee mothers who attend national conferences. Radiation safety education is provided throughout training, and rotation schedules are modified to accommodate trainee preferences regarding radiation exposure during and after pregnancy.

Policies regarding parental leave for medical trainees are widely disparate (20,21). Insufficient length and lack of paid leave have been associated with parental stress and shorter breastfeeding durations (22). In contrast, shared caregiving has been associated with safer births and decreased risk of postpartum depression (23). The fellowship program’s approach to parental leave involves a personalized discussion with each expecting FIT regarding her/his options for parental leave, incorporating paid and unpaid leave, vacation time, and allowances through the Family and Medical Leave Act and American Board of Internal Medicine (24). We encourage new mothers to take 12 weeks leave and have created flexibility in the rotation schedule to accommodate longer leaves or unanticipated events. We also strongly encourage new fathers to take extended leave at intervals that are best for their families. Since establishing this practice, new fathers have each taken between 2 to 6 weeks leave, an improvement from the previous average of 1 week. In 2017, PWIC successfully advocated for a change in the health system’s House Staff Policy to allow for 12 weeks of parental leave for dual physician-trainee couples, instead of the previously permitted 6 weeks per household (25).

Finally, fertility preservation is a common and important consideration for FITs and ECs embarking on extended training pathways like cardiology (26). PWIC members have led departmental workshops on this topic and are creating a resource guide for FITs.

To address the known gender disparities in recognizing women trainee and faculty scholarship (27), PWIC publishes a quarterly newsletter and uses social media to promote women’s accomplishments. The newsletters are disseminated to deans, the division chief, and the faculty. Both interventions have helped us engage men and women from within and outside our institution as allies.

After identifying a gender disparity in invited Grand Rounds speakers, PWIC collectively nominated over 20 women for Grand Rounds lectureships for the 2019–2020 year. This year, one-half of the invitations were extended to women, as compared to 7% to 15% inprior years,and 9 of 18 speakers have been women. We also recruit women faculty to participate in fellow didactics, resulting in an increased representation of women at journal clubs and case conferences. We are tracking metrics like the annual proportions of women honorees of clinical, research, and teaching awards.

From 2016 to 2019, women comprised 50% of the general cardiology fellowship, making our program one of the most gender-balanced in the country. The PWIC program is presented to fellowship applicants on every interview day. Over the last 5 years, 36% of our new faculty recruits have been women, a remarkable feat given the low numbers of female cardiologists in training and in practice. To build on this success, the Women’s Faculty Development Program, an official division-level initiative, will focus on strategies for career advancement for ECs and midcareer faculty. The Program’s initial projects include an analysis of wage disparities by gender with the Department of Medicine and education on compensation for trainees entering the market.

The ACC considers diversity and inclusion essential to its mission for cardiology and as a professional society (1).Through the Penn Women in Cardiology, we strive to serve as an example of how a dedicated strategy and vision for culture change can engage and promote existing FIT and EC talent, provide value for under-represented populations in our field, and attract and retain future diverse generations of leaders in cardiovascular medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, including Drs. Thomas P. Cappola, Frank E. Silvestry, Monika Sanghavi, Victor A. Ferrari, and the women fellows and faculty for their inspiration and support in the creation of this program.

Dr. Reza is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Human Genome Research Institute Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service T32 Award in Genomic Medicine (T32 HG009495). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors' institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC author instructions page.

REFERENCES

- 1.Douglas PS, Williams KA, Walsh MN. Diversity matters. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1525–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AAMC. Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2017. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492560/1-3-chart.html Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 3.ACGME. ACGME Data Resource Book. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publicationsand-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 4.Stone AT, Carlson KM, Douglas PS, et al. Assessment of subspecialty choices of men and women in internal medicine from 1991 to 2016. JAMA Intern Med 2019;180:140–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagsi R, Biga C, Poppas A, et al. Work activities and compensation of male and female cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:529–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah RU. The $2.5 million wage gap in cardiology. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:674–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis SJ, Mehta LS, Douglas PS, et al. Changes in the professional lives of cardiologists over 2 decades. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:452–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, et al. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation 2017; 135:506–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarma AA, Nkonde-Price C, Gulati M, et al. Cardiovascular medicine and society: the pregnant cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douglas PS, Rzeszut AK, Merz CNB, et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among us internal medicine trainees: factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:682–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert MA. #Me_who anatomy of scholastic, leadership, and social isolation of underrepresented minority women in academic medicine. Circulation 2018;138:451–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oza NM, Breathett K. Women in cardiology: fellows’ perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65: 951–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma G, Narula N, Ansari-Ramandi MM, et al. The importance of mentorship and sponsorship: tips for fellows-in-training and early career cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep 2019;1:232–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma G, Sarma AA, Walsh MN, et al. 10 recommendations to enhance recruitment, retention, and career advancement of women cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:1839–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greguletz E, Diehl MR, Kreutzer K. Why women build less effective networks than men: the role of structural exclusion and personal hesitation. Hum Relat 2019;72:1234–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.AAMC. Table B3: Number of active residents, by type of medical school, GME specialty, and sex. Available at:https://www.aamc.org/data/493922/report-on-residents-2018-b3table.html Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 17.Yong CM, Abnousi F, Rzeszut AK, et al. Sex differences in the pursuit of interventional cardiology as a subspecialty among cardiovascular fellows-in-training. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2019;12: 219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Society of Cardiology. Women in electrophysiology: choose the right option for you. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-&-Events/EHRA-Congress/Congress-resources/News/women-in-electrophysiologychoose-the-right-option-for-you Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 19.Kay J, Reza N, Silvestry FE. Establishing and expecting a culture of support for breastfeeding cardiology fellows. JACC Case Rep 2019;1: 680–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magudia K, Bick A, Cohen J, et al. Childbearing and Family Leave Policies for Resident Physicians at Top Training Institutions. JAMA 2018;320: 2372–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varda BK, Glover M. Specialty board leave policies for resident physicians requesting parental leave. JAMA 2018;320:2374–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamond R. Promoting sensible parenting policies: leading by example. JAMA 2019;321: 645–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Promundo. State of the world’s fathers: unlocking the power of men’s care. Available at: https://stateoftheworldsfathers.org/report/stateof-the-worlds-fathers-helping-men-step-up-to-care/ Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 24.American Board of Internal Medicine. Special training policies. Available at: https://www.abim.org/certification/policies/general/special-training-policies.aspx Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 25.Penn Medicine. Graduate medical education. Available at: http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/gme/Default.aspx Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 26.Stentz NC, Griffith KA, Perkins E, et al. Fertility and Childbearing Among American Female Physicians. J. Womens Health 2016;25:1059–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotenstein LS, Berman RA, Katz JT, et al. Making the voices of female trainees heard. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:339–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]