Abstract

Objectives

Patients with osteoarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis have lower cancer-related mortality than the general population. We examined risks of solid cancers at 16 sites in elderly patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis (KHOA) or ankylosing spondylitis.

Methods

In this population-based retrospective cohort study, we used US Medicare data from 1999 to 2010 to identify cohorts of persons with KHOA or ankylosing spondylitis, and a general population group without either condition, who were followed through 2015. We compared cancer incidence among groups, adjusted for age, sex, race, socioeconomic characteristics, geographic region, smoking and comorbidities.

Results

We studied 2 701 782 beneficiaries with KHOA, 13 044 beneficiaries with ankylosing spondylitis, and 10 859 304 beneficiaries in the general population group. Beneficiaries with KHOA had lower risks of cancer of the oropharynx, oesophagus, stomach, colon/rectum, hepatobiliary tract, pancreas, larynx, lung, and ovary than the general population. However, beneficiaries with KHOA had higher risks of melanoma, renal cell cancer, and cancer of the bladder, breast, uterus and prostate. Associations were similar in ankylosing spondylitis, with lower risks of cancer of the oesophagus, stomach, and lung, and higher risks of melanoma, renal cell cancer, and cancer of the renal pelvis/ureter, bladder, breast, and prostate.

Conclusion

Lower risks of highly prevalent cancers, including colorectal and lung cancer, may explain lower cancer-related mortality in patients with KHOA or ankylosing spondylitis. Similarities in cancer risks between KHOA and AS implicate a common risk factor, possibly chronic NSAID use.

Keywords: cancer, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis

Rheumatology key messages

Elderly patients with knee/hip osteoarthritis have lower risks of gastrointestinal and respiratory tract cancers.

Elderly knee/hip OA patients have higher risks of melanoma and kidney, bladder, breast and prostate cancer.

Elderly AS patients had a pattern of site-specific cancer risks similar to those with knee/hip osteoarthritis.

Introduction

Symptomatic knee and hip osteoarthritis (KHOA) affects 45% and 25% of older Americans, respectively, by age 85 [1, 2]. Two large population-based studies in the United States and Sweden reported lower cancer-related mortality among persons with knee osteoarthritis [3, 4]. Only one previous study has examined site-specific cancer incidence among patients with osteoarthritis, and reported lower than expected incidences of colorectal, stomach and lung cancer, and a higher incidence of prostate cancer [5]. The lower risk of colorectal cancer was attributed to chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory spinal arthritis that typically begins in young adulthood and persists throughout life. NSAIDs are the main pharmacological treatment. Mortality risks in AS are 30% to 50% higher than the general population, but cancer-related mortality was markedly lower than expected in two of three studies that reported cause-specific mortality [6–8].

The factors responsible for lower mortality due to cancer in KHOA and AS are unclear. One possible explanation may be that chronic treatment with NSAIDs results in lower cancer incidences. Use of NSAIDs is well-established to be associated with a reduced risk of esophageal, stomach and colorectal cancer [9, 10]. Whether NSAID use is associated with risks of other cancers is unclear, possibly because their effects on other cancers are weaker, or because chronic use, rather than the more common intermittent use, is needed to have an effect [11].

The aim of this study was to compare risks of solid cancers in patients with KHOA and patients with AS to those in the general population. We also compared the pattern of site-specific cancer associations between KHOA and AS, as shared patterns may implicate a common risk factor. We studied population-based cohorts of US Medicare beneficiaries age 65 or older, because cancer is largely a disease of the elderly.

Methods

Data source and study groups

We used Medicare fee-for-service hospitalization and outpatient data from 1999 to 2015 in this retrospective cohort study. We identified beneficiaries with either KHOA or AS, and an unaffected general population group and followed them for the development of cancer. We used International Classification of Diseases-9-Clinical Modification (ICD9) diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient claims to identify beneficiaries in each study group. We only used outpatient claims from in-person visits with physicians. Data were provided by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) through a data use agreement. The study was approved by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases institutional review board, which waived the requirement for informed consent.

Beneficiaries with KHOA were identified as those with two or more diagnosis claims of ICD9 715.X5 or 715.X6 at least seven days apart by either an orthopedist or rheumatologist in 1999–2013. A single claim by a specialist has a positive predictive value for KHOA of 0.83 [12]. Beneficiaries with AS were identified by the presence of two or more claims with a diagnosis code of 720.0 (positive predictive value 0.88) at least seven days apart in 1999–2013 [13]. To increase the specificity of this group, we excluded beneficiaries who also had two or more codes for either rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis. We identified a general population group that did not have any KHOA claims by a specialist or AS claims.

From among these groups, we identified beneficiaries who entered Medicare at age 65 during 1999–2010, were not enrolled in a managed care plan, and lived in the United States, to form groups of incident beneficiaries for analysis. Because patients in the disease groups more often entered Medicare early in the study period, and because the incidence of some cancers changed over time, we selected a random sample of the general population group to have the same distribution of year of Medicare entry as beneficiaries in the disease groups, frequency matched to the arthritis groups in a 4:1 ratio. Assembly of the groups is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online.

Identification of cancers

We identified cancers based on the presence of at least two inpatient or outpatient claims with the same 4-digit ICD9 diagnosis code occurring at least 30 days apart. In validation studies, this definition had positive predictive values of 0.66–0.77, and specificities of 0.82–0.99, for lung, colorectal and breast cancer [14, 15]. We then collapsed these to three-digit codes for site-specific cancers: oropharynx (ICD9 codes 140–149), oesophagus (150), stomach (151), colorectal (153, 154), hepatobiliary (155, 156), pancreas (157), larynx (161), lung (162), melanoma (172), female breast (174), uterus (179, 182), ovary (183), prostate (185) and urinary bladder (188). We examined renal cell carcinoma (1890) separately from cancer of the renal pelvis and ureter (1891, 1892) because of known associations of the latter with analgesic use [16]. We did not study hematological malignancies, nervous system or musculoskeletal cancers, and did not examine nonmelanoma skin cancer because incident skin cancer is difficult to identify in administrative data. We do not report results for testicular or cervical cancer because of small numbers.

Statistical analysis

Beneficiaries were followed, and person-years tabulated, from Medicare enrolment to the date of first claim with the related cancer code, death, enrolment in a managed care plan, or end of study (30 September 2015). We computed the incidence of cancer at each site by disease group. Beneficiaries could contribute events to more than one cancer site, as is standard for computation of cancer incidences [17]. We excluded cancer claims recorded during the beneficiaries’ first year in Medicare because these may have been prevalent rather than incident cancers [14]. To validate our incidence data, we compared incidences in the general population group to those of US Cancer Statistics registries [18].

We compared age-sex standardized incidences of cancers between beneficiaries in each arthritis group and the general population group. We used Poisson regression analysis to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRR) for KHOA and AS relative to the general population group, adjusted for age, sex, race (white, black, other), poverty, area-based socioeconomic status, geographic region, current smoking, and presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and chronic liver disease. Current smoking and each comorbidity were based on CMS Chronic Condition Warehouse data (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). Information on past smoking was not available. We designated beneficiaries as poor if they received subsidies for medical insurance premiums. As a second measure of socioeconomic status, we use a validated measure based on the economic characteristics of the beneficiary’s zip code of residence [19]. For 335 783 (2.4%) beneficiaries with missing data on zip code, we imputed state-specific values. We classified beneficiary residence into the nine US census divisions.

In addition, we determined if associations were similar in men and women with KHOA. We also examined the association of KHOA with tobacco-related cancers (lung, larynx, oropharynx, oesophagus, renal cell and bladder) separately among current smokers and non-smokers. We repeated this analysis using COPD as a surrogate for past or current smoking exposure. To determine whether propensity for preventive health care mediated associations with three screening-dependent cancers (melanoma, breast or prostate), we examined the subset of KHOA and general population beneficiaries who received influenza vaccination during 75% or more of their years of follow-up, based on vaccination administration claims.

We used SAS version 9.4 software for all analyses.

Results

We studied 2 701 782 beneficiaries with KHOA, 13 044 beneficiaries with AS and 10 859 304 beneficiaries in the general population group. A total of 63% of the KHOA group were women, while 66% in the AS group were men (Table 1). Beneficiaries in the general population group were slightly poorer than those in either arthritis group, and had lower prevalences of COPD, diabetes, and chronic kidney or liver disease. Median follow-up ranged from 8.75 years in the general population group to 10.8 years in the KHOA group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of beneficiaries at study entry

| Knee/hip osteoarthritis (n = 2 701 782) | Ankylosing spondylitis (n = 13 044) | General population (n = 10 859 304) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry, years | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| Men, n (%) | 981 760 (36.3) | 8609 (66.0) | 5 462 613 (50.3) |

| White, n (%) | 2 389 902 (88.5) | 11 858 (90.9) | 9 091 044 (83.7) |

| Black, n (%) | 215 423 (8.0) | 514 (3.9) | 1 095 819 (10.1) |

| Other, n (%) | 96 457 (3.5) | 672 (5.2) | 672 441 (6.2) |

| Poor, n (%) | 383 088 (14.2) | 1442 (11.0) | 1 945 643 (17.9) |

| Socioeconomic scorea | 2.0 (5.6) | 2.9 (5.7) | 1.5 (5.6) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 307 797 (11.4) | 1613 (12.4) | 1 487 196 (13.7) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 832 751 (30.8) | 4333 (33.2) | 2 844 489 (26.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1 212 799 (44.9) | 5481 (42.0) | 3 814 183 (35.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 879 796 (32.5) | 4858 (37.2) | 2 718 942 (25.0) |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 310 716 (11.5) | 1659 (12.7) | 936 095 (8.6) |

| Years of follow-up, median (range) | 10.8 (0.2 to 16.75) | 9.75 (0.2 to 16.75) | 8.75 (0.2 to 16.75) |

| Total person-years | 28 874 346.5 | 128 262.83 | 96 033 852.17 |

Based on seven census indicators of the zip code of residence. Zip codes at the national average on each of the seven measures would have a score of 0. Zip codes that were 1 standard deviation below the national average on each measure would have a score of –7, while those at 1 standard deviation above the national average on each measure would have a score of +7.

Incidences of cancer in the general population group were very similar to those reported in US Cancer Statistics data, except for a higher incidence of ovarian cancer and lower incidence of lung cancer (Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online). In our cohort, 1.5%, 1.6% and 2.0% of patients in the general population, KHOA and AS groups, respectively, had more than one cancer during observation.

Age-sex standardized incidences of cancer of the oropharynx, oesophagus, stomach, colon/rectum, hepatobiliary tract, pancreas, larynx, lung and ovary were lower in the KHOA group than in the general population group (Table 2). IRRs were lowest for lung cancer (IRR 0.60; 95% CI: 0.59, 0.62) and laryngeal cancer (IRR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.63, 0.68). Associations for these sites were similar or slightly attenuated in the multivariable-adjusted analysis but remained lower in the KHOA group than in the general population group. In contrast, age-sex standardized incidences of melanoma, renal cell cancer, and cancer of the renal pelvis, bladder, breast, uterus and prostate were higher in beneficiaries with KHOA. Results were similar in the multivariable-adjusted analysis, with two exceptions: there was no association between KHOA and cancer of the renal pelvis (IRR 0.97; 95% CI: 0.93, 1.01), and the association with prostate cancer was stronger (IRR 1.43; 95% CI: 1.42, 1.45).

Table 2.

Cancer incidence among Medicare beneficiaries with knee or hip osteoarthritis and beneficiaries in the general population group

| General populationa | Knee/hip osteoarthritisa | Age-sex adjusted IRR (95% CI) | Multivariable- adjusted IRR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oropharynx | 45 460; 47.4 (46.9, 47.9) | 9464; 37.1 (36.2, 37.9) | 0.78 (0.76, 0.80) | 0.88 (0.85, 0.90) |

| Oesophagus | 25 923; 27.0 (26.6, 27.4) | 4810; 20.4 (19.7, 21.0) | 0.75 (0.73, 0.78) | 0.81 (0.77, 0.83) |

| Stomach | 25 542; 26.6 (26.2, 27.0) | 5463; 21.1 (20.5, 21.7) | 0.79 (0.76, 0.82) | 0.88 (0.84, 0.91) |

| Colorectal | 162 820; 170.7 (169.8, 171.5) | 38 299; 138.0 (136.6, 139.5) | 0.80 (0.79, 0.82) | 0.89 (0.88, 0.90) |

| Hepatobiliary | 35 841; 37.3 (36.9, 37.8) | 8232; 30.4 (29.7, 31.2) | 0.82 (0.79, 0.84) | 0.78 (0.76, 0.80) |

| Pancreas | 42 944; 44.7 (44.3, 45.2) | 10 808; 38.7 (37.9, 39.5) | 0.87 (0.84, 0.89) | 0.86 (0.84, 0.88) |

| Larynx | 22 459; 23.4 (23.1, 23.8) | 3595; 15.3 (14.7, 15.8) | 0.65 (0.63, 0.68) | 0.77 (0.74, 0.80) |

| Lung | 276 345; 289.3 (288.2, 290.4) | 48 648; 175.1 (173.5, 176.7) | 0.60 (0.59, 0.62) | 0.68 (0.67, 0.69) |

| Melanoma | 65 613; 68.5 (68.0, 69.1) | 26 500; 102.0 (100.7, 103.3) | 1.48 (1.46, 1.51) | 1.49 (1.46, 1.52) |

| Renal cell | 59 683; 62.3 (61.7, 62.8) | 20 471; 78.1 (76.9, 79.2) | 1.25 (1.23, 1.27) | 1.25 (1.23, 1.28) |

| Renal pelvis/ureter | 12 923; 13.4 (13.2, 13.7) | 3781; 14.6 (14.1, 15.1) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) |

| Bladder | 99 960; 104.5 (103.8, 105.2) | 27 000; 113.0 (111.6, 114.4) | 1.08 (1.06, 1.10) | 1.10 (1.08, 1.12) |

| Breast | 228 036; 485.2 (483.2, 487.2) | 100 929; 564.5 (561.0, 568.1) | 1.16 (1.15, 1.18) | 1.29 (1.28, 1.31) |

| Uterus | 43 929; 91.6 (90.7, 92.5) | 17 948; 97.8 (96.3, 99.3) | 1.06 (1.04, 1.09) | 1.14 (1.12, 1.17) |

| Ovary | 30 543; 63.6 (62.8, 64.3) | 9650; 52.4 (51.3, 53.5) | 0.83 (0.80, 0.85) | 0.90 (0.87, 0.93) |

| Prostate | 358 577; 778.5 (776.0, 781.1) | 97 810; 993.1 (986.8, 999.3) | 1.27 (1.26, 1.29) | 1.43 (1.42, 1.45) |

Data are number of events; incidence per 100 000 person-years (95% CI).

Adjusted for age, sex, race, poverty, area-based socioeconomic score, census division, current smoking, and presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and chronic liver disease.

Risks were very similar in women and men across cancer sites (Fig. 1). An exception was bladder cancer, for which there was no association among women but a slight increased risk among men. Results were also similar if only the first observed cancer was analysed (Supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) in knee or hip osteoarthritis by gender. Lines represent 95% CIs

The risk of lung cancer was lower among both smokers and non-smokers in the KHOA group compared with the general population (Table 3). Reduced risks were also present in both smokers and non-smokers for cancer of the larynx, oesophagus and oropharynx, although these risks were substantially lower among smokers. Risk of renal cell cancer was higher among beneficiaries with KHOA in both non-smokers and, not than smokers. KHOA was associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer among non-smokers but a reduced risk among smokers. The pattern of associations was similar when beneficiaries were stratified by the presence of COPD, indicating that associations were robust to the measure of smoking exposure.

Table 3.

Multivariable-adjusted incidence rate ratios for tobacco-related cancers in beneficiaries with knee or hip osteoarthritis compared with the general population

| Non-smoker | Smoker | COPD absent | COPD present | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 0.66 (0.65–0.67) | 0.67 (0.65–0.68) | 0.66 (0.65–0.67) | 0.67 (0.65–0.68) |

| Larynx | 0.81 (0.77–0.85) | 0.67 (0.63–0.72) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | 0.67 (0.63–0.70) |

| Oropharynx | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | 0.69 (0.65–0.72) | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) | 0.74 (0.71–0.77) |

| Oesophagus | 0.81 (0.77–0.84) | 0.73 (0.68–0.78) | 0.81 (0.77–0.85) | 0.71 (0.68–0.74) |

| Renal cell | 1.27 (1.25–1.30) | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | 1.23 (1.21–1.27) | 1.15 (1.12–1.19) |

| Bladder | 1.16 (1.14–1.18) | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) | 1.13 (1.11–1.16) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) |

Models included age, sex, race, poverty, area-based socioeconomic score, census division, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, and reciprocally, COPD and current smoking as covariates.

Among 579 140 KHOA and 1 174 028 general population beneficiaries who consistently received influenza vaccinations, risks of melanoma (multivariable-adjusted IRR 1.21; 95% CI: 1.18, 1.26), breast cancer (IRR 1.17; 95% CI: 1.15, 1.19) and prostate cancer (IRR 1.11; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.13) in the KHOA group were attenuated compared with results in the overall group.

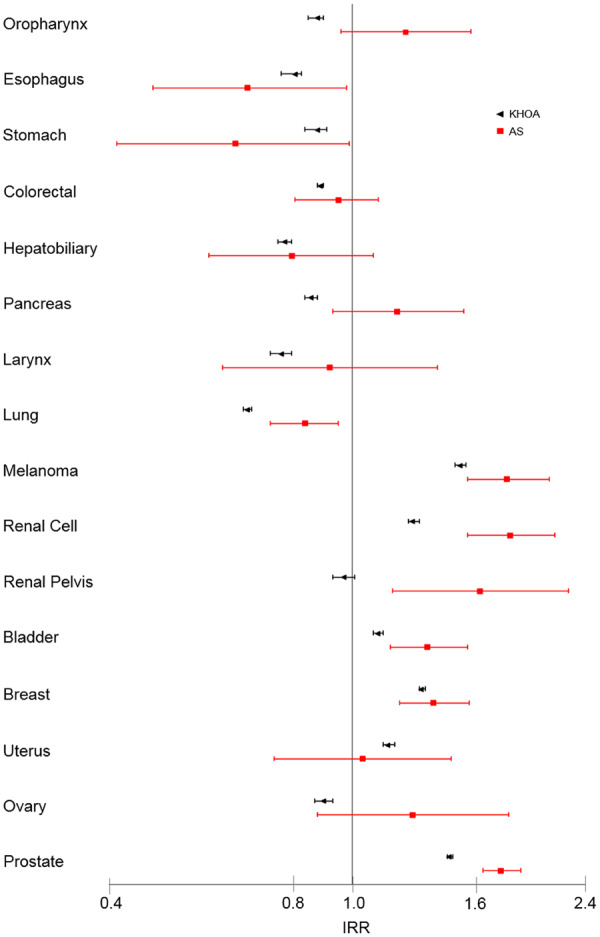

To determine whether associations were specific to KHOA, we compared incidences among beneficiaries with AS to those of the general population group. Age-sex standardized incidences of cancer of the oesophagus, stomach, colon/rectum and lung were significantly lower in the AS group than the general population group, while incidences of melanoma, renal cell cancer, and cancer of the renal pelvis/ureter, bladder, breast and prostate were higher in the AS group (Table 4). All but the association with colorectal cancer remained significant in the multivariable-adjusted analysis. The pattern of associations in AS was very similar to that in KHOA (Fig. 2). Differences included increased risks of cancer of the oropharynx, pancreas, renal pelvis/ureter, uterus and ovary in the AS group. Notably, the adjusted IRR of AS for cancer of the renal pelvis/ureter was 1.60 (95% CI: 1.16, 2.22), while the adjusted IRR of KHOA was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.93, 1.01).

Table 4.

Cancer incidence among Medicare beneficiaries with ankylosing spondylitis and beneficiaries in the general population group

| General populationa | Ankylosing spondylitisa | Age-sex adjusted IRR (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted IRR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oropharynx | 45 460; 47.4 (46.9, 47.9) | 71; 48.2 (36.5, 59.9) | 1.01 (0.79, 1.30) | 1.22 (0.96, 1.55) |

| Oesophagus | 25 923; 27.0 (26.6, 27.4) | 25; 16.5 (9.8, 23.2) | 0.61 (0.40, 0.92) | 0.68 (0.48, 0.98) |

| Stomach | 25 542; 26.6 (26.2, 27.0) | 21; 14.6 (8.1, 21.2) | 0.55 (0.35, 0.86) | 0.65 (0.42, 0.99) |

| Colorectal | 162 820; 170.7 (169.8, 171.5) | 180; 138.5 (117.2, 159.8) | 0.81 (0.69, 0.95) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.10) |

| Hepatobiliary | 35 841; 37.3 (36.9, 37.8) | 43; 29.9 (20.5, 39.2) | 0.80 (0.58, 1.09) | 0.80 (0.59, 1.08) |

| Pancreas | 42 944; 44.7 (44.3, 45.2) | 67; 52.7 (39.4, 66.0) | 1.18 (0.91, 1.52) | 1.18 (0.93, 1.51) |

| Larynx | 22 459; 23.4 (23.1, 23.8) | 25; 17.0 (10.0, 24.0) | 0.73 (0.48, 1.10) | 0.92 (0.62, 1.37) |

| Lung | 276 345; 289.3 (288.2, 290.4) | 274; 210.0 (183.9, 236.2) | 0.73 (0.64, 0.83) | 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) |

| Melanoma | 65 613; 68.5 (68.0, 69.1) | 170; 122.7 (103.4, 142.0) | 1.79 (1.52, 2.10) | 1.77 (1.53, 2.07) |

| Renal cell | 59 683; 62.3 (61.7, 62.8) | 156; 106.9 (89.6, 124.1) | 1.71 (1.46, 2.02) | 1.79 (1.53, 2.11) |

| Renal pelvis/ureter | 12 923; 13.4 (13.2, 13.7) | 37; 26.3 (17.4, 35.2) | 1.95 (1.39, 2.74) | 1.60 (1.16, 2.22) |

| Bladder | 99 960; 104.5 (103.8, 105.2) | 198; 126.7 (108.6, 144.8) | 1.21 (1.05, 1.40) | 1.32 (1.15, 1.53) |

| Breast | 228 036; 485.2 (483.2, 487.2) | 248; 577.4 (505.6, 649.4) | 1.19 (1.05, 1.35) | 1.35 (1.19, 1.54) |

| Uterus | 43 929; 91.6 (90.7, 92.5) | 37; 83.7 (56.7, 110.8) | 0.92 (0.66, 1.27) | 1.04 (0.75, 1.44) |

| Ovary | 30 543; 63.6 (62.8, 64.3) | 32; 72.4 (47.3, 97.5) | 1.13 (0.80, 1.61) | 1.25 (0.88, 1.78) |

| Prostate | 358 577; 778.5 (776.0, 781.1) | 899; 1142.0 (1067.4, 1216.7) | 1.46 (1.37, 1.57) | 1.73 (1.62, 1.86) |

Data are number of events; incidence per 100 000 person-years (95% CI).

Adjusted for age, sex, race, poverty, area-based socioeconomic score, census division, current smoking, and presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and chronic liver disease.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) in knee or hip osteoarthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Lines represent 95% CIs

Discussion

In this population-based study, older Americans with KHOA had lower risks of cancer at many sites in the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, including lung and colon/rectum, than the general elderly population. However, persons with KHOA also had higher risks of melanoma, breast, uterine, urinary tract and prostate cancer. The strongest protective associations were for the risks of lung and laryngeal cancer, while the greatest increased risks were for melanoma and prostate cancer. Site-specific associations were broadly similar among beneficiaries with AS, implicating a shared aetiology.

A previous cohort study of 91 583 inpatients with osteoarthritis reported lower than expected risks of stomach, colorectal and lung cancer, with IRRs that ranged from 0.66 for stomach cancer in women to 0.88 for colorectal cancer in men [5]. Risk of biliary tract cancer was also lower. Men with osteoarthritis had increased risks of melanoma and prostate cancer. Studies of cancer developing after total knee or hip arthroplasty, done to investigate implant safety, provide additional evidence [20, 21]. Patients with arthroplasty had lower subsequent risks of esophageal, stomach, colorectal, lung and laryngeal cancer, and increased risks of melanoma and prostate cancer, compared with the general population. Interpretation of these studies is limited by the consideration that arthroplasty recipients are a selected and healthier group, but the associations with gastrointestinal and respiratory tract cancers, melanoma and prostate cancer were similar to our findings [22].

The mechanisms by which KHOA, or factors associated with it, may be associated with site-specific cancer risks are unclear. Although KHOA produces elevated circulating levels of byproducts of cartilage, bone or synovial damage, there is no evidence that these are either cancer-promoting or protective. The major risk factors for KHOA, apart from age and sex, are injury, malalignment and obesity [23]. We did not have data on obesity or physical activity, and therefore could not adjust for these factors. Obesity/overweight is associated with increased risks of colorectal cancer, adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia, and cancer of the liver, gallbladder, pancreas and ovary, yet we found lower risks of these cancers in beneficiaries with KHOA [24]. Conversely, obesity/overweight is a shared risk factor for KHOA and postmenopausal breast, uterine and renal cell carcinoma. The increased risk of these cancers in KHOA may be related to a higher prevalence of obesity. Smoking has been associated with a lower risk of knee osteoarthritis [25]. While the percent of smokers was slightly higher in the general population group than in beneficiaries with KHOA, our analysis adjusted for smoking. Additionally, among smokers, KHOA was associated with lower risks of lung, laryngeal, oropharyngeal and esophageal cancer, indicating that smoking did not account for the association between KHOA and these cancers.

Preventive health behavior appeared to mediate some of the association between KHOA and risk of melanoma, breast and prostate cancer, as the risks of these screening-related cancers were attenuated among beneficiaries who consistently had influenza vaccinations. However, risks of these cancers remained elevated among those with KHOA in the subset of beneficiaries with consistent influenza vaccination.

Medications used to treat KHOA may be associated with the observed cancer risks. A total of 40 to 55% of patients with KHOA take non-aspirin NSAIDs regularly, while 10% to 20% take acetaminophen regularly [26, 27]. Non-aspirin NSAID use is associated with lower risks of colorectal, esophageal and stomach cancer and colonic adenomas [10]. Chronic NSAID use is likely responsible for the reduced risk of these cancers among beneficiaries with KHOA. Evidence of associations between NSAID use and risk of hepatobiliary, pancreatic and oropharyngeal cancer is limited [11]. Lung cancer had the lowest relative risk among all cancers in beneficiaries with KHOA. Previous studies of NSAID use and lung cancer risk have had inconsistent results, although protective associations have been more commonly reported with longer durations of NSAID use than with dose [11, 28, 29]. Risk of postmenopausal breast cancer has been reported to be lower in women who used non-aspirin NSAIDs, suggesting that the increased risk among women with KHOA may not be related to medication use [30–32]. Associations with melanoma, uterine and ovarian cancer have been either null or conflicting [11].

Long-term non-aspirin NSAID use has been associated with increased risk of renal cell carcinoma in some, but not all, cohort studies, raising the possibility that NSAID use contributed to the increased risk among beneficiaries with KHOA [33–35]. Associations with prostate cancer risk have been conflicting, although studies reporting increased risks with chronic NSAID use are notably more common for prostate cancer than for other sites [34, 36–41]. We found divergent associations between KHOA and the risk of bladder cancer between smokers and non-smokers, but in the direction opposite to that reported for NSAID use [42]. Although some studies have suggested associations between chronic acetaminophen use and bladder cancer or renal cell carcinoma, the body of evidence indicates no association with solid cancers [43].

Beneficiaries with AS and KHOA shared lower risks of esophageal, stomach and lung cancer, and higher risks of melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and bladder and prostate cancer. Patients with AS and KHOA may both experience chronic joint damage, low-grade inflammation, and possibly reduced physical activity, but how these relate to the observed site-specific cancer associations is unclear. The other main factor common to both AS and KHOA is use of NSAIDs, and the pattern of site-specific associations is consistent with prior studies on site-specific associations with chronic NSAID use. Risk estimates of esophageal and stomach cancer, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and prostate cancer were more extreme in AS than KHOA, which may also implicate NSAID use, as patients with AS would be anticipated to have used NSAIDs for longer durations than patients with KHOA. Whether urolithiasis may contribute to the risk of renal and urothelial cancers in AS is unknown [44]. Risk of colorectal cancer was lower in the AS group than the general population group in the age/sex standardized analysis, but this association did not remain after adjustment for the presence of comorbidities, particularly chronic kidney disease. Registry studies from Sweden reported lower risks of colorectal cancer and marginally higher risks of kidney and prostate cancer in persons with AS, while studies from Taiwan included groups with demographic features atypical of AS [45–49].

Our study has several limitations. We did not have data on factors such as obesity or physical activity that may mediate associations between KHOA and cancer. Also, we did not have data on particular cancer-specific risk factors, such as viral hepatitis or human papilloma virus infection, but there is no evidence these infections differ between persons with and without arthritis. We did not have complete medication data, and so could not test associations with NSAID use directly. Also, 10% of Americans age 50 or older use NSAIDs regularly, and we might expect similar use in the general population group [50]. Therefore, the arthritis and general population groups represent groups with different degrees of NSAID use, rather than users and non-users. Similarly, the general population group likely includes persons with KHOA who did not meet the study definition; their presence in the control group would attenuate associations between KHOA and cancers. Given the widespread use of nonprescription NSAIDs, detailed medication records over many years, starting in middle age, would be optimal to examine associations with NSAID use, but such studies are difficult to perform. Long follow-up is needed to accommodate cancer latency periods, but this is difficult to achieve in the large samples needed to study less common cancers. Patients with musculoskeletal conditions that require chronic NSAID treatment and that begin in middle age or earlier may be used as a surrogate for NSAID use to test cancer risks. Such an approach is analogous to that used in occupational epidemiology where job titles are used as surrogates for environmental exposures that were not directly measured. TNF inhibitors were used by <4% of patients with AS, possibly reflecting a delay in uptake or that many elderly patients were not judged appropriate candidates. Given this low prevalence, it is unlikely that use of TNF inhibitors had a meaningful effect on cancer risks. We do not know if similar risks apply to persons younger than age 65. The smaller number of beneficiaries with AS may have limited our power to detect associations with less common cancers. As with any study of administrative data, inaccuracies in coding may be present.

Lower risks of highly prevalent cancers, including lung and colorectal cancer, may underlie lower rates of cancer-related mortality in patients with KHOA. The lower risks of gastrointestinal and respiratory tract cancers in KHOA and AS are consistent with associations previously reported for NSAIDs. Beneficiaries with KHOA and AS appear to be at increased risk for melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and prostate cancer. Further study is needed to determine whether these risks are related to medication use, or if other factors are responsible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Data were provided by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services under a data use agreement, which prohibits public dissemination of the primary data. Qualified investigators may apply to this agency for access to the primary data. Orchid ID 0000-0003-1857-9367.

Funding: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health (ZIA-AR-041153).

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1. Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG. et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2008;59:1207–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA. et al. One in four people may develop symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in his or her lifetime. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:1372–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turkiewicz A, Kiadaliri AA, Englund M.. Cause-specific mortality in osteoarthritis of peripheral joints. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mendy A, Park J, Vieira ER.. Osteoarthritis and risk of mortality in the USA: a population-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:1821–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas E, Brewster DH, Black RJ, Macfarlane GJ.. Risk of malignancy among patients with rheumatic conditions. Int J Cancer 2000;88:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prati C, Puyraveau M, Guillot X, Verhoeven F, Wendling D.. Deaths associated with ankylosing spondylitis in France from 1969 to 2009. J Rheumatol 2017;44:594–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Exarchou S, Lie E, Lindström U. et al. Mortality in ankylosing spondylitis: results from a nationwide population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bakland G, Gran JT, Nossent JC.. Increased mortality in ankylosing spondylitis is related to disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1921–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dulai PS, Singh S, Marquez E. et al. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer in individuals with previous colorectal neoplasia: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;355:i6188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brusselaers N, Lagergren J.. Maintenance use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of gastrointestinal cancer in a nationwide population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Silva MT, Galvao TF, Zimmerman IR, Pereira MG, Lopes LC.. Non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs of the primary chemoprevention on non-gastrointestinal cancer: summary of evidence. Curr Pharm Des 2012;18:4047–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrold LR, Yood RA, Andrade SE. et al. Evaluating the predictive value of osteoarthritis diagnoses in an administrative database. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1881–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dubreuil M, Peloquin C, Zhang Y. et al. Validity of ankylosing spondylitis diagnoses in The Health Improvement Network. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25:399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Setoguchi S, Solomon DH, Glynn RJ. et al. Agreement of diagnosis and its date for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors between Medicare claims and cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control 2007;18:561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whyte JL, Engel-Nitz NM, Teitelbaum A, Gomez Rey G, Kallich JD.. An evaluation of algorithms for identifying metastatic breast, lung, or colorectal cancer in administrative claims data. Med Care 2015;53:e49–e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Landolph J, Gerkins V, Henderson BE.. Analgesics, cigarette smoking, and other risk factors for cancer of the renal pelvis and ureter. Cancer Res 1989;49:1045–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, Edwards BK.. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist 2007;12:20–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.2001–2015 Database: National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results SEER*Stat Database: NPCR and SEER Incidence – USCS 2001–2015 Public Use Research Database, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. Released June 2018, based on the November 2017. submission. www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/public-use.

- 19. Ward MM. Socioeconomic status and the incidence of ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;51:563–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Visuri T, Pukkala E, Pulkkinen P, Paavolainen P.. Decreased cancer risk in patients who have been operated on with total hip and knee arthroplasty for primary osteoarthrosis: a meta-analysis of 6 Nordic cohorts with 73,000 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2003;74:351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Onega T, Baron J, MacKenzie T.. Cancer after total joint arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:1532–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hunt LP, Ben-Shlomo Y, Whitehouse MR, Porter ML, Blom AW.. The main cause of death following primary total hip and knee replacement for osteoarthritis: a cohort study of 26,766 deaths following 332,734 hip replacements and 29,802 deaths following 384,291 knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharma L, Kapoor D, Issa S.. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006;18:147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IARC. Absence of excess body fatness. IARC Handb Cancer Prev 2018;16:1–646. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hui M, Doherty M, Zhang W.. Does smoking protect against osteoarthritis? Meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kingsbury SR, Hensor EMA, Walsh CAE, Hochberg MC, Conaghan PG.. How do people with knee osteoarthritis use osteoarthritis pain medications and does this change over time? Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abbate LM, Jeffreys AS, Coffman CJ. et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with nonsurgical osteoarthritis treatment among patients in outpatient clinics. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:1141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slatore CG, Au DH, Littman AJ, Satia JA, White E.. Association of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with lung cancer: results from a large cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:1203–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hernández-Díaz S, García Rodríguez LA.. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2007;120:1565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson TW, Anderson KE, Lazovich D, Folsom AR.. Association of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002;11:1586–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bardia A, Olson JE, Vachon CM. et al. Effect of aspirin and other NSAIDs on postmenopausal breast cancer incidence by hormone receptor status: results from a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;126:149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang X, Smith-Warner SA, Collins LC. et al. Use of aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen and postmenopausal breast cancer incidence. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3468–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cho E, Curhan G, Hankinson SE. et al. Prospective evaluation of analgesic use and risk of renal cell cancer. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1487–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sørensen HT, Friis S, Nørgård B. et al. Risk of cancer in a large cohort of nonaspirin NSAID users: a population-based study. Br J Cancer 2003;88:1687–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu W, Park Y, Purdue MP, Giovannucci E, Cho E.. A large cohort study of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and renal cell carcinoma incidence in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:1865–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu Y, Chen J-Q, Xie L. et al. Effect of aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on prostate cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2014;12:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Langman MJ, Cheng KK, Gilman EA, Lancashire RJ.. Effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on overall risk of common cancer: case-control study in general practice research database. BMJ 2000;320:1642–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murad AS, Down L, Davey Smith G. et al. Associations of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug and paracetamol use with PSA‐detected prostate cancer: findings from a large, population‐based, case–control study (the ProtecT study). Int J Cancer 2011;128:1442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Skriver C, Dehlendorff C, Borre M. et al. Low-dose aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and prostate cancer risk: a nationwide study. Cancer Causes Control 2016;27:1067–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Veitonmäki T, Tammela TL, Auvinen A, Murtola TJ.. Use of aspirin, but not other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is associated with decreased prostate cancer risk at the population level. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:938–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kang M, Ku JH, Kwak C, Kim HH, Jeong CW.. Effects of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, statin, and cox2 inhibitor on the developments of urological malignancies: a population-based study with 10-year follow-up data in Korea. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50:984–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Daugherty SE, Pfeiffer RM, Sigurdson AJ. et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer: a pooled analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:721–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weiss NS. Use of acetaminophen in relation to the occurrence of cancer: a review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes Control 2016;27:1411–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jakobsen AK, Jacobsson LT, Patschan O, Askling J, Kristensen LE.. Is nephrolithiasis an unrecognized extra-articular manifestation in ankylosing spondylitis? A prospective population-based Swedish national cohort study with matched general population comparator subjects. PLoS One 2014;9:e113602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Feltelius N, Ekbom A, Blomqvist P.. Cancer incidence among patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Sweden 1965-95: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1185–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hemminki K, Liu X, Ji J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K.. Autoimmune disease and subsequent digestive tract cancer by histology. Ann Oncol 2012;23:927–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu X, Ji J, Forsti A. et al. Autoimmune disease and subsequent urological cancer. J Urol 2013;189:2262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sun LM, Muo CH, Liang JA. et al. Increased risk of cancer for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Scand J Rheumatol 2014;43:301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chang CC, Chang CW, Nguyen PA. et al. Ankylosing spondylitis and the risk of cancer. Oncol Lett 2017;14:1315–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhou Y, Boudreau DM, Freedman AN.. Trends in the use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general U.S. population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014;23:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.