Abstract

Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) is prevalent around the world and is a causative agent of skin and soft tissue infections in healthy individuals. Particularly, Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL)-positive CA-MRSA strains occasionally cause life-threatening infections, such as septic pulmonary emboli (SPE) and infectious endocarditis. However, severe infections caused by PVL-positive CA-MRSA strains have rarely been reported in Japan. For the first time, this study reports the case of a 20-year-old Japanese college athlete with life-threatening PVL-positive CA-MRSA USA300 clone infection, including sepsis, SPE, and skin and soft tissue infections with iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis.

Keywords: community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, USA300 clone, sepsis, bacteremia, acute respiratory distress syndrome

Introduction

USA300 clone is one of the highest pathogenic and global epidemic community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) clones and carries the Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes and arginine catabolic mobile element. It is a sequence-type (ST) 8-staphylococcal cassette chromosome (SCC) mec type IV (ST8-IV) (1). PVL targets polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages and induces cell death via necrosis or apoptosis (2). Therefore, PVL-positive CA-MRSA causes severe diseases, such as skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), necrotizing pneumonia, and bacteremia (3). Recently in Japan, USA300 clone infection has been increasing in not only hospitals but also in community settings (4). Here we report the case of a Japanese college athlete with septic pulmonary emboli (SPE) secondary to infectious iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and abscesses caused by the USA300 clone.

Case Report

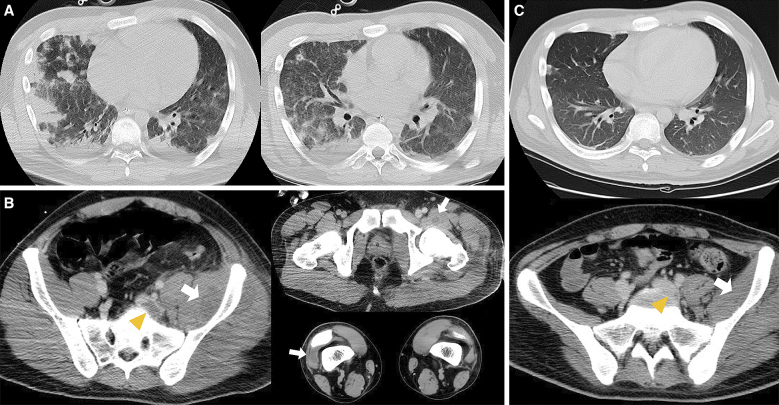

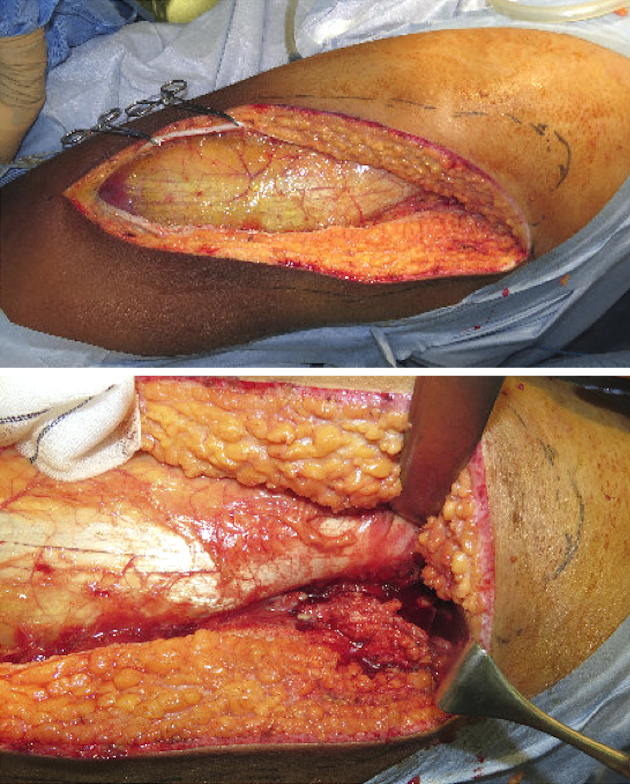

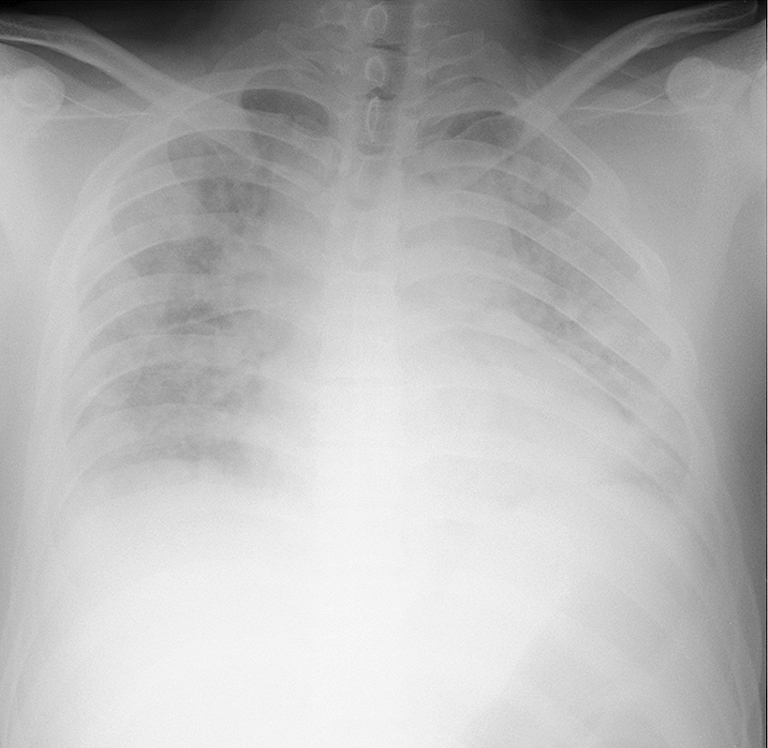

A 20-year-old male student was admitted to our emergency department for dyspnea since 2 weeks. He had no previous medical and travel history. His physical examination revealed the following: Glasgow Come Scale score, E4V4M6; blood pressure, 137/83 mmHg; heart rate, 148 beats/min; respiratory rate, 40 breaths/min; and body temperature, 40.4°C. He had several abrasions on his extremities caused by playing rugby football. Initial laboratory test results of the patient are listed in Table 1. His chest radiography revealed bilateral alveolar shadows (Figure 1), and computed tomography (CT) revealed pneumonia with a cavity in the right upper lobe, which was suspected to be SPE (Figure 2A). Abdominal CT revealed SSTIs of the hip and thigh with abscesses and iliofemoral DVT (Figure 2B). Intravenous administration of vancomycin combined with clindamycin was initiated. Subsequently, he underwent surgical drainage and debridement of the SSTIs of the hip and left thigh, followed by puncture drainage of bilateral knee joint abscess in the operating room (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Initial Results of the Patient’s Laboratory Test.

| Variables | Parameter | Reference rage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count | 31,000 | cells/μL | 4000–8000 | cells/μL |

| Platelet count | 11.3 × 104 | cells/μL | 15–35 × 104 | cells/μL |

| C-reactive protein | 33.1 | mg/dL | <0.3 | mg/dL |

| Fibrin/fibrinogen degradation product | 17.1 | μg/dL | <5.0 | μg/dL |

| D-dimer | 30 | μg/mL | <0.5 | μg/mL |

| Creatinine | 1.56 | mg/dL | 0.60–1.20 | mg/dL |

| Presepsin | 3,445 | pg/mL | <500 | pg/mL |

Figure 1.

Chest radiography revealed bilateral alveolar shadows.

Figure 2.

A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest revealed septic pulmonary emboli. B) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed left iliofemoral thrombosis (arrow head) and skin and soft tissue infection of the hip and left thigh with abscesses (arrow). C) CT after 1 month revealed the resolution of the iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis (arrow head).

Figure 3.

Surgical drainage and debridement of the skin and soft tissue infection of the hip and left thigh in the operating room.

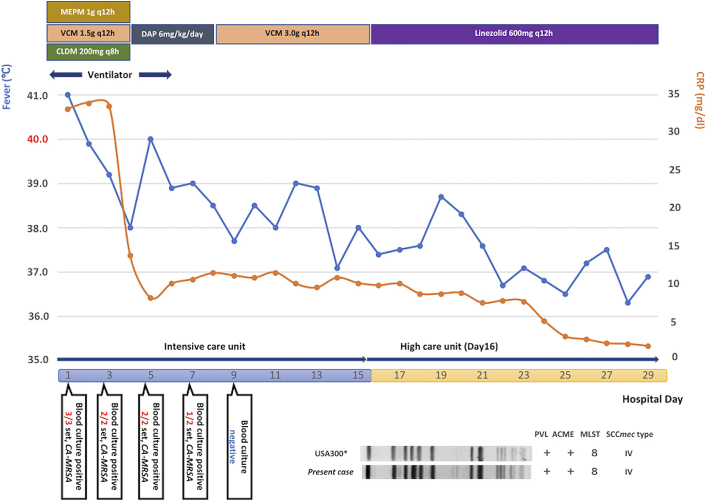

The analysis of the patient’s initial three sets of blood culture, sputum, urine, wounds, and abrasions revealed the presence of MRSA. PCR detection of virulence genes, production of PVL, SCC mec typing, multilocus sequence typing, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis identified the strain as USA300 clone (Figure 4). The patient recovered from the septic shock; no further SSTIs were encountered. CT after 1 month revealed the complete disappearance of iliofemoral DVT without new pulmonary embolization, concurrent infective endocarditis, or vertebral osteomyelitis (Figure 2C). The patient was treated for septic osteomyelitis of the hip joint for 8 weeks. The patient finally became ambulatory and was discharged from our hospital after rehabilitation therapy for 11 weeks.

Figure 4.

Clinical course and molecular typing of MRSA strain of the patient. ACEM arginine catabolic mobile element, CA-MRSA community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, CLDM clindamycin, CRP C-reactive protein, DAP daptomycin, MEPM meropenem, MLST multilocus sequence typing, PVL Panton–Valentine leukocidin, SCC staphylococcal cassette chromosome, VCM vancomycin.

Discussion

Outbreaks of PVL-positive CA-MRSA among club teams, including American football, soccer, rugby, or wrestling teams as well as interscholastic, intercollegiate, and professional athletic teams have been reported (5), (6). Athletes are particularly vulnerable to CA-MRSA infection because of the frequency of skin injury, close-contact situations, and sharing of equipment, which is customary in athletic settings (7). The USA300 clone is widely disseminated in both community and healthcare settings, which resulted in its emergence as a worldwide pandemic clone (3). In contrast, PVL-negative ST30-IV, ST30-V, ST59-IV, ST59-V, ST89-II, and ST89-V clones are the predominant CA-MRSA strains known in Asian countries, including Japan (8). Although the prevalence of USA300 clone has been increasing in both Japanese communities and hospital settings in recent years, we could not find any report of a life-threatening infection caused by USA300 clone in Japanese athletes to date (4). The transmission route of USA300 clone in this case still remains unknown, whereas we found the report that USA300 clone was detected in 42% of nasal swabs from professional football players and staff members (9). Therefore, we strongly hypothesize that the USA300 clone of this case was derived from the nasal cavity of his teammate. To demonstrate our hypothesis, nasal screening of the collegiate rugby team is now ongoing.

SPE has a high mortality rate (<20%), and death is caused most frequently due to septic shock accompanied by multiple organ failure. It is an uncommon syndrome characterized by the embolization of an infected thrombus from a primary infectious site into the venous circulation. In the present case, sustained bacteremia lasting for 7 days was considered extremely remarkable. It was difficult to perform a surgical drainage of the deep abscess of the hip joint as a source of infection that spread to the iliofemoral vein and caused DVT. In the field of emergency medicine, we recommend for the suspicion of SSTIs as a source of SPE.

In conclusion, we raise an alarm that PVL-positive CA-MRSA, especially the USA300 clone, could be a threat among collegiate football players in Japan. Hence, we recommend the active surveillance and eradication of nasal colonization of PVL-positive CA-MRSA among collegiate athletes.

Article Information

Conflicts of Interest

None

Authors’ Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: YR, TJ

Contributed to interpretation of data: MM, YH, KT, NH, TS, NN

Approved the final version to be submitted: MT, AT

Approval by Institutional Review Board (IRB)

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tokyo Medical University Hachioji Medical Center (H-232).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

References

- 1.Takadama S, Nakaminami H, Sato A, et al. Dissemination of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clone in multiple hospitals in Tokyo, Japan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(11):1211e1-e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genestier AL, Michallet MC, Prevost G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin directly targets mitochondria and induces Bax-independent apoptosis of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(11):3117-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nimmo GR. USA300 abroad: Global spread of a virulent strain of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(8):725-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi T, Nakaminami H, Ohtani H, et al. An outbreak of severe infectious diseases caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clone among hospitalized patients and nursing staff in a tertiary care university hospital. J Infect Chemother. Forthcoming 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romano R, Lu D, Holtom P. Outbreak of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections among a collegiate football team. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):141-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lear A, McCord G, Peiffer J, et al. Incidence of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization and soft tissue infection among high school football players. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(4):429-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karanika S, Kinamon T, Grigoras C, et al. Colonization with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and risk for infection among asymptomatic athletes: A Systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(2):195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakaminami H, Sugiyama T, Okamura Y, et al. Comparative analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from outpatients of dermatology unit in hospitals and clinics. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25(3):233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazakova SV, Hageman JC, Matava M, et al. A clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among professional football players. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(5):468-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]