Significance

The atmospheric chemistry of mercury, a global priority pollutant, is key to its transport and deposition to the surface environment. Assessments of its risks to humans and ecosystems rely on an accurate understanding of global mercury cycling. This work shows that the chemical reactions and rates currently employed to interpret Hg chemistry in the atmosphere fails to explain observed atmospheric mercury concentrations and deposition. We report that model simulations incorporating recent developments in the photoreduction mechanisms of the oxidized forms of mercury (HgI and HgII) lead to a significant model underestimation of global observations of these oxidized species in the troposphere and their surface wet deposition. This implies that there must be currently unidentified mercury oxidation processes in the troposphere.

Keywords: atmospheric chemistry, gas-phase mercury reactivity, tropospheric chemistry, mercury photoreduction, atmospheric modeling

Abstract

Mercury (Hg), a global contaminant, is emitted mainly in its elemental form Hg0 to the atmosphere where it is oxidized to reactive HgII compounds, which efficiently deposit to surface ecosystems. Therefore, the chemical cycling between the elemental and oxidized Hg forms in the atmosphere determines the scale and geographical pattern of global Hg deposition. Recent advances in the photochemistry of gas-phase oxidized HgI and HgII species postulate their photodissociation back to Hg0 as a crucial step in the atmospheric Hg redox cycle. However, the significance of these photodissociation mechanisms on atmospheric Hg chemistry, lifetime, and surface deposition remains uncertain. Here we implement a comprehensive and quantitative mechanism of the photochemical and thermal atmospheric reactions between Hg0, HgI, and HgII species in a global model and evaluate the results against atmospheric Hg observations. We find that the photochemistry of HgI and HgII leads to insufficient Hg oxidation globally. The combined efficient photoreduction of HgI and HgII to Hg0 competes with thermal oxidation of Hg0, resulting in a large model overestimation of 99% of measured Hg0 and underestimation of 51% of oxidized Hg and ∼66% of HgII wet deposition. This in turn leads to a significant increase in the calculated global atmospheric Hg lifetime of 20 mo, which is unrealistically longer than the 3–6-mo range based on observed atmospheric Hg variability. These results show that the HgI and HgII photoreduction processes largely offset the efficiency of bromine-initiated Hg0 oxidation and reveal missing Hg oxidation processes in the troposphere.

Annually, about 8 Gg of mercury (Hg) are released to the atmosphere from present-day anthropogenic (∼39%) and natural (∼6%) sources, and reemissions of previously deposited Hg from natural and anthropogenic sources (∼55%) (1). The average concentration of Hg in the atmosphere is relatively low, in the range of 1–2 ng/m3 (equivalent to ∼100–200 parts per quadrillion mixing ratio). Earth’s atmosphere is therefore a minor Hg reservoir of ∼5 Gg, compared with terrestrial soil and marine Hg pools (1,450 and 280 Gg, respectively) (2). However, the atmosphere is a key component of the global Hg cycle because it facilitates the planetwide dispersion of the metal. This global dynamic is governed by a complex combination of emissions, atmospheric chemical processing, transport, and surface deposition (3, 4). In the atmosphere, Hg cycles between elemental Hg0 and oxidized monovalent HgI and divalent HgII forms (5, 6). Oxidation mechanisms of atmospheric Hg have been reviewed several times [e.g., Si and Ariya, 2018 (7) and references therein]. The current view is that the slow gas-phase oxidation of Hg0 by hydroxyl radical (OH) (8) and ozone (O3) is frequently complemented or replaced by the much more efficient oxidation by atomic bromine (Br) (9, 10). Although the knowledge of the amount and distribution of tropospheric Br has improved during the last decade (11, 12), more measurements of tropospheric Br concentrations and their spatial distribution are sorely needed to reduce uncertainty in atmospheric kinetic and transport models of Hg oxidation based on Br chemistry.

Mercury is released to the atmosphere mostly as gaseous elemental Hg0, which is currently assumed to be oxidized to HgII by a two-step mechanism (6, 9, 10, 13). The first step is initiated by photochemically produced Br atoms to form HgBr, a radical HgI intermediate that can then photolytically or thermally decompose back to Hg0, or be further oxidized to HgII compounds by atmospheric radicals such as NO2, HO2, Br, OH, I, Cl, BrO, ClO, and IO (6, 9, 13, 14). Based on this scheme, and despite Br being a minor atmospheric constituent, Holmes et al. (14) proposed that Hg0 oxidation by Br is potentially the dominant oxidation pathway at a global scale. Field and model studies have reported evidence of the Br-initiated oxidation over different environments where Br chemistry is active and relatively abundant such as the polar regions [e.g., ref. (15)], salt lakes [e.g., ref. (16)], tropical marine boundary layer (13) and free troposphere (17). Several models, however, still consider Hg0 oxidation by O3 and OH as the main pathway (18, 19), particularly in the continental atmosphere.

Once oxidized, gaseous HgII species are more water soluble and particle reactive, and eventually partition into aerosols and clouds, before efficient deposition to the Earth’s surface by wet and dry deposition processes. Recent theoretical work has shown that divalent (HgII: syn-HgBrONO, anti-HgBrONO, HgBrOOH, HgBrOH, HgBrNO2, HgBr2, HgCl2, HgBrOCl, HgBrI, HgBrOBr, HgBrOI) (20) and monovalent (HgI: HgBr, HgCl, HgOH, HgI) (21) species strongly absorb ultraviolet-visible light. Therefore, daytime solar radiation leads to efficient gas-phase photolysis, which can dominate HgI and HgII reduction in the atmosphere and shorten the lifetime of oxidized Hg species compared to previous reaction schemes where Hg reduction was restricted to the aqueous cloud phase (6). Experimental evidence of photoreduction of oxidized Hg has been reported from observations on the remote Tibetan Plateau (22) and in urban air (23). The rapid photodissociation of syn-HgBrONO has been suggested to produce the HgBrO radical, which upon reaction with volatile organic compounds swiftly forms HgBrOH (24). Finally, a recent computational study has reported quantitative photodissociation channels and photoproducts of the likely major gaseous oxidized HgII compounds (syn-HgBrONO, HgBrOOH, HgBrO, and HgBrOH), and constructed a quantitative mechanism of the photochemical and thermal conversion between Hg0, HgI, and HgII species in the atmosphere (25).

These recent theoretical works suggest that gas-phase photodissociation of oxidized HgI,II is a key process in the global atmospheric cycling of this metal. However, the influence of these combined new photochemical mechanisms on the redox chemistry, lifetime, and surface deposition of Hg in the global atmosphere is currently unknown. Here, a state-of-the-art global Hg chemical transport model is used to evaluate the impact of the recently proposed Hg photoreduction mechanisms against atmospheric Hg measurements. The evaluation includes the different photodissociation processes for HgI and HgII, and their impact on atmospheric Hg concentrations and surface deposition patterns, lifetime, and vertical profiles in the troposphere.

Chemical Mechanisms and Global Model Simulations

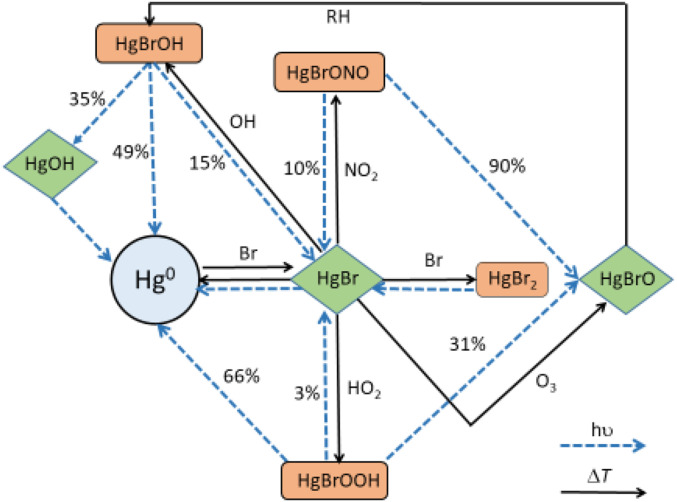

Fig. 1 shows the main reactions for thermal and photochemical conversion between Hg0, HgI, and HgII species (25). syn-HgBrONO and HgBrOOH are considered the major gaseous oxidized HgII species from Br-initiated two-step Hg0 oxidation (6, 26, 27). It has been calculated that following gas-phase photolysis, syn-HgBrONO breaks down to HgBrO (90%) and HgBr (10%) (24, 25), and HgBrOOH yields Hg0 (66%), HgBrO (31%), and HgBr (3%) (25). The computed tropospheric photolysis rate of the HgBrO radical (2.95 × 10−2⋅s−1) (25) is too slow to compete with the proposed reaction of the radical with methane [pseudo–first-order rate, k′ = 11 s−1 at 298 K and 1 atm (24)] to form HgBrOH. Note that the equivalent reaction of HgBrO with NO2 has a k′ = 2 × 10−2⋅s−1 at 298 K and 1 atm (24). Therefore, the photolysis of syn-HgBrONO does not lead directly to photoreduction but to the formation, with a 90% yield, of another HgII species, namely HgBrOH. Photodissociation of HgBrOH results in Hg0 (49%), HgOH (35%), and HgBr (15%). The resulting HgI photoproducts (HgBr and HgOH) will also efficiently photodissociate to Hg0 (21). Summed together, the photolysis of syn-HgBrONO, HgBrOOH, and HgBrOH reduces oxidized HgI,II to Hg0 directly (38%) and indirectly (62%) (25). Hence, the overall combination of the different photodissociation pathways indicates that the suggested main gaseous oxidized Hg compounds, both HgI and HgII, rapidly return directly and indirectly to Hg0 via gas-phase photolysis. This results in Hg0 being the predominant product of oxidized HgI,II gas-phase photoreduction in the atmosphere.

Fig. 1.

Thermal and photochemical reactions of major mercury species in the atmosphere, including the HgI (green) and HgII (orange) photoreduction processes. The photoproduct yields are shown as percentage. The reaction HgBr + O3 to yield HgBrO proposed in this work is discussed in detail in SI Appendix, Supplementary Note 2.

Recently, a large collaborative multimodel effort was conducted to investigate the impact of different Hg oxidation mechanisms (i.e., slow reaction with ozone and OH radical, and faster Br-initiated oxidation) and emissions on global Hg distributions (28, 29). However, the redox mechanisms tested in this multimodel evaluation did not consider the photoreduction of HgI and HgII species. To evaluate the global impact of these photoreduction mechanisms, and their competition with thermal Hg oxidation, we use the global chemical transport model GLEMOS (Global European Monitoring and Evaluation Program Multimedia Modeling System) (Methods). Several simulation tests (Table 1) were performed with the model using different combinations of the state-of-the-art chemical mechanisms. The first test (run 1) included the Br-initiated two-step oxidation of Hg0, including oxidation by OH, with thermal reduction of HgI and no photoreduction of HgI and HgII (Methods, SI Appendix, Table S1, reactions R1–R7). The second test (run 2) consisted of the Br and OH oxidation chemistry and photodissociation of HgI and HgII according to the chemical scheme shown in Fig. 1 (see SI Appendix, Table S1, reactions R1–R10). We also conducted two model sensitivity runs to assess the influence of the uncertainties in the key thermal reaction and photolysis rates as reported in the literature. In the first run (run 2a, Table 1), we take the upper limit of the uncertainty in key oxidation reactions and the lower limit of the uncertainty in Hg reduction reactions. This is done to test maximum Hg oxidation within the limit of kinetic uncertainties. The opposite, i.e., minimum Hg oxidation within uncertainty, was tested in run 2b. The evaluation was focused on a comparison of modeled and measured concentrations of Hg0, oxidized Hg (HgI + HgII), as well as HgII wet deposition. Model tests were carried out for the period 2007–2013 with the first 6 y as a model spin up and the year 2013 as the control run.

Table 1.

Model runs

| Run ID | Scenario |

| Run 1 | Two-step Hg° oxidation by Br (R1–R4) and OH (R5–R7) [see chemical scheme in SI Appendix, Table S1], with no photolysis of Hg(I) and Hg(II) species. |

| Run 2 | Two-step Hg° oxidation by Br (R1–R4) and OH (R5–R7), with photolysis of Hg(I) and Hg(II) species (R8–R10). |

| Run 2a | Run 2 with the value of reaction rates R1–R10 that would maximize Hg° oxidation, within the published uncertainty. |

| Run 2b | Run 2 with the value of reaction rates R1–R10 that would minimize Hg° oxidation, within the published uncertainty. |

| Run 3 | Run 2 with new reaction R11 (oxidation of HgBr by O3 to form HgBrO). |

| Run 4 | Run 2 with atmospheric bromine concentration increased by a factor of 2. |

As mentioned above, the gas-phase oxidation of Hg0 by O3 (Hg + O3 → HgO + O2) has been considered as a major oxidation pathway in the atmosphere. The rate coefficient for this reaction was measured to be 8.4 × 10−17 exp(−11.7 kJ mol−1/RT) cm3 molecule−1⋅s−1 (30), which implies a bond dissociation energy D0(HgO) ≥ 88 kJ mol−1. However, high-level theoretical calculation shows that the Hg–O bond is in fact rather weak, with a reported value ∼17 kJ mol−1 (31). This means that not only this reaction is too slow to effectively oxidize Hg in the troposphere, but also that any formed HgO has a high probability of promptly dissociating [for further details see the comprehensive discussion of Hynes et al. (32) and SI Appendix, Supplementary Note 1]. Therefore, here we do not consider gas-phase oxidation of Hg0 by O3. Similarly, due to the very rapid HgOH dissociation, the OH-initiated Hg0 oxidation is considered not to be important (8, 9), although it is included in our simulations (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Impact of HgI and HgII Photoreduction on Simulated Hg Concentrations

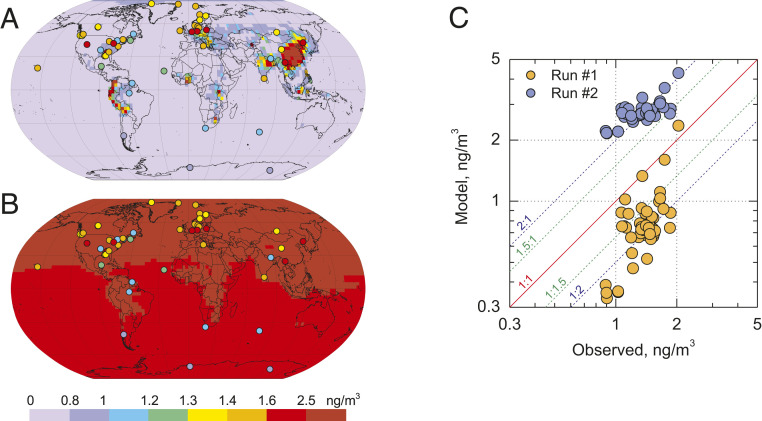

The total atmospheric Hg burden and, as a consequence, air concentration of Hg species and their lifetime depend on both the Hg redox chemistry and on global emissions. The Hg lifetime against deposition in the model varies from 3.5 mo in run 1 without photoreduction to 20 mo in run 2 when photolysis of HgI and HgII species is included, with calculated lifetimes of 16.3 and 22.4 mo for sensitivity run 2a and run 2b, respectively (Table 2). From observed atmospheric variability of Hg, the lifetime against deposition should be in the range of 3–6 mo (6). The total Hg0 mass increases by a factor of 5.7 from 1,390 Mg (run 1) to 7,865 Mg (run 2) (Table 2). This is due to photoreduction of (HgI + HgII) species back to Hg0. The unrealistically long atmospheric lifetimes against deposition obtained in model runs 2, 2a, and 2b are confirmed by comparison of observed and simulated standard deviations (SDs) of Hg0 concentrations across ground-based sites. We consider here the relative SD instead of the absolute one (6) due to considerable difference in mean concentration levels simulated in different tests. Model runs significantly deviate from Hg0 ground-based measurements with 43% underestimation for run 1 and 99% overestimation for run 2 (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The short lifetime in run 1 leads to very low surface Hg0 concentrations (0.3–1 ng m−3). In contrast, application of the photoreduction mechanism in run 2 leads to much higher Hg0 concentrations (2–3 ng m−3), which overestimate observations by a factor of 2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Table 2.

Total Hg lifetime against deposition, mass burden in the troposphere, and statistics of the model evaluation against measurements

| Parameter | Obs | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 2a | Run 2b |

| Total Hg0 mass, Mg | 3,856* | 1,390 | 7,865 | 6,485 | 8782 |

| Total HgI,II mass, Mg | 359† | 127 | 46 | 88 | 20 |

| Hg lifetime against deposition, months | 3.5 | 20 | 16.3 | 22.4 | |

| Hg0 concentration | |||||

| Mean, ng m−3 | 1.38 ± 0.25 | 0.79 ± 0.33 | 2.75 ± 0.34 | 2.39 ± 0.36 | 2.98 ± 0.33 |

| Relative bias, %‡ | −42.8 | 99.0 | 72.9 | 115.8 | |

| Spatial CC§ | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.7 | 0.67 | |

| HgI,II concentration | |||||

| Mean, pg m−3 | 11.7 ± 10.6 | 32.8 ± 13.9 | 5.7 ± 4.3 | 7.2 ± 4.6 | 4.7 ± 4.2 |

| Relative bias, % | 180.9 | −51.0 | −38.4 | −59.3 | |

| Spatial CC | 0.62 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.01 | |

| Hg wet deposition | |||||

| Mean, g km−2⋅y−1 | 9.1 ± 4.5 | 8.9 ± 3.0 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| Relative bias, % | −1.8 | −65.6 | −77.7 | −93.6 | |

| Spatial CC | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

Total Hg0 mass up to 20-km altitude estimated based on the measured vertical profiles of Hg0 concentration up to 12 km (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) and linear decrease of Hg0 concentration down to zero at 20 km.

Total HgI,II mass up to 20-km altitude estimated based on the aircraft measurement of the vertical profile of HgI,II concentration (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B).

Relative bias: ; M and O are modeled and observed values, respectively.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (CC):.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of modeled and observed spatial patterns of elemental mercury (Hg0) concentration in the atmosphere for run 1 (A, no photolysis), and run 2 (B, HgI,II photolysis), and scatter plot of the model-to-measurement comparison at ground-based sites (C) in 2013.

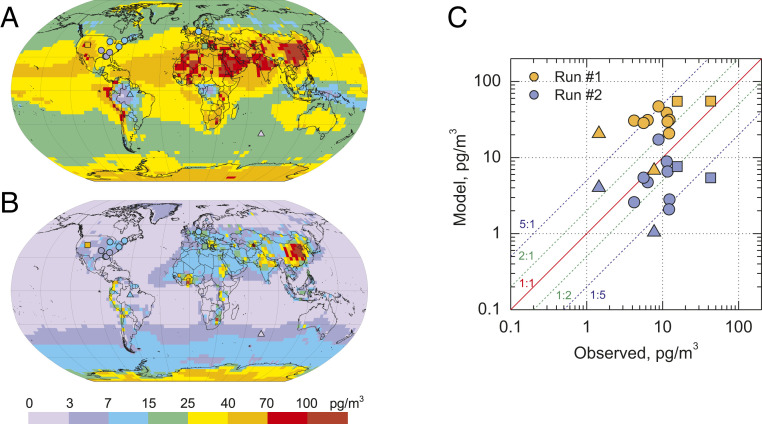

Simulation of the chemical mechanism without HgI,II photolysis (run 1) leads to a large overestimation (181%) of ground-based measurements of oxidized Hg (Fig. 3) despite underestimation of total Hg mass in the atmosphere (Table 2). In contrast, photoreduction of HgI and HgII (run 2) results in strong underestimation (51%) of oxidized Hg observations (Table 2). The model simulations considering the kinetics uncertainties, run 2a and run 2b, lead to underestimations of observed HgI,II of 38 and 59%, respectively. Note that ground-based observations of oxidized Hg based on KCl-coated denuder techniques are associated with large uncertainty, and possibly biased low by up to one order of magnitude (33, 34). This low bias in HgII observations would indicate even stronger underestimation in run 2. Furthermore, a recent experimental study has reported the reaction rate constant of HgBr + NO2 to HgBrONO to be 3–11 times lower than that predicted by theory (35), and incorporated in our model. Also, a new theoretical study, not included in this work, proposes the reduction of HgBrO by reaction with CO (HgBrO + CO → HgBr + CO2) (36). All of this implies that the model underestimation of HgII observations would be even larger with the inclusion of the results from these two very recent studies.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of modeled and measured spatial patterns of oxidized mercury (HgI + HgII) atmospheric concentrations for run 1 (A, no photolysis) and run 2 (B, HgI,II photolysis), and scatter plot of the model-to-measurement comparison at ground-based sites (C) in 2013. Circles present sea-level sites in northern midlatitudes; squares, high-elevation sites; triangles, sites in the southern hemisphere.

The effect of including photochemistry of oxidized HgI,II is smaller near source regions, which are affected directly by anthropogenic emissions, and increase with distance from sources, in particular at low latitudes (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). We therefore note a marked regionality in the relative differences from the different model runs. Large increases of total Hg atmospheric mass from run 1 to run 2 partly compensate for the lack of oxidation capacity of the atmosphere. Nevertheless, the mass of global atmospheric HgI,II decreases from 127 Mg (run 1) to 46 Mg (run 2) following efficient photoreduction (Table 2).

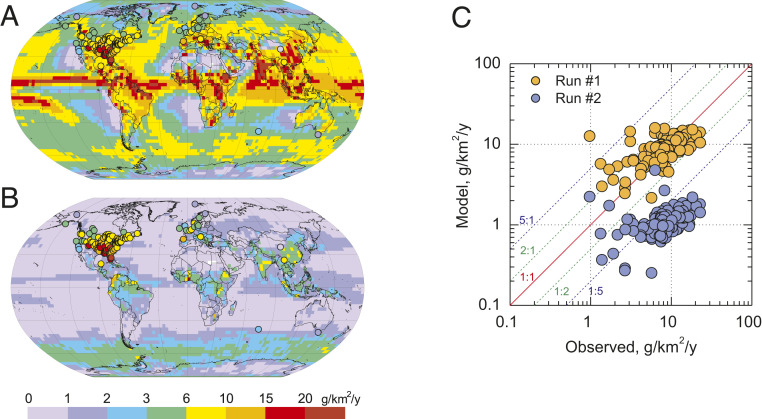

Mercury wet deposition is largely affected by the rate of Hg oxidation to yield soluble and particle-reactive HgI,II species in the free troposphere. Comparison with measurements shows that implementation of the new photoreduction mechanism leads to a large underestimation (66%) of Hg wet deposition fluxes in North America and Europe (Fig. 4). The largest decrease occurs in the tropics and the smallest over source regions, mirroring the changes of oxidized Hg concentrations. The apparently correct estimation of wet deposition in run 1 (Table 2 and Fig. 4) is a consequence of the large overestimation (181%) of ground-level oxidized Hg.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of modeled and measured spatial patterns of Hg wet deposition for run 1 (A, no photolysis) and run 2 (B, HgI,II photolysis), and scatter plot of the model-to-measurement comparison at ground-based sites (C) in 2013.

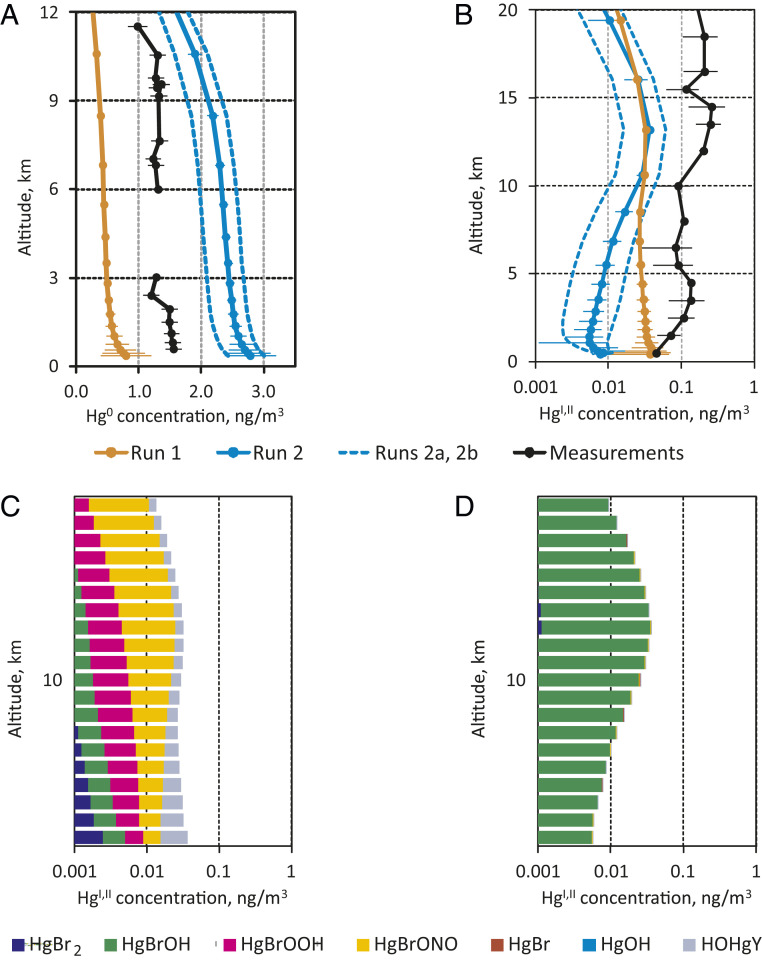

More insight into the effect of photoreduction can be obtained from the analysis of vertical profiles of Hg0 and oxidized Hg species (Fig. 5 and Methods). The difference in chemical mechanisms leads to significant differences between the modeled Hg0 vertical profiles and the measured one (Fig. 5A). Both model tests and measurements in the northern hemisphere midlatitudes (30–60°N) show elevated oxidized Hg concentrations in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere (UT/LS). However, the effect of the photoreduction mechanism differs in the upper and lower troposphere. In the lower troposphere (below 5 km), where influence of redox chemistry is smaller, the photoreduction results in a decrease of HgI,II concentrations. In contrast, in the UT/LS higher levels of Hg0 due to the longer lifetime caused by photoreduction (Fig. 5A) lead to increased production of oxidized Hg (Fig. 5B). It should be noted that both model tests are unable to reproduce the HgI,II concentration profile throughout the troposphere. This model underestimation of the HgI,II concentration profile is larger for run 2, even considering the kinetic parameter uncertainties (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Modeled and observed vertical profiles of atmospheric concentration of Hg0 (A) and HgI,II (B) over northern midlatitudes; and contribution of various species to HgI,II concentration for run 1 (C, no photolysis) and run 2 (D, HgI,II photolysis).

Not including photoreduction of HgI,II in the model leads to the globally integrated tropospheric predominance of HgBrONO and HgBrOOH among other oxidized Hg species (Fig. 5C). At the surface, HgBr2, HgBrOH, and HOHgY also contribute to the modeled HgII budget in run 1. Implementation of the photoreduction mechanisms drastically changes the composition of oxidized Hg to only HgBrOH (Fig. 5D). This results from the combined rapid photolysis of HgBrONO and HgBrOOH to HgBrO (Fig. 1), and the subsequent reaction of the radical with methane to yield HgBrOH (24).

We conducted two further exploratory model runs (Table 1) including an oxidation reaction not to our knowledge documented in the literature (HgBr + O3 → HgBrO + O2, Run#3, see SI Appendix, Supplementary Note 2) and one simulation in which Br concentrations are increased by a factor of 2 (run 4), to assess the sensitivity of the model results to the uncertainties in tropospheric Br concentrations. The results of these two additional tests, summarized in SI Appendix, Table S2, show that the model still overestimates the observed Hg0 concentration (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), although to a smaller extent, and significantly underestimates the measurements of HgII (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) by 40 and 15% for run 3 and run 4, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S2). Similarly, wet deposition is still largely underestimated under these exploratory simulations (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) as well as the tropospheric concentration profile of HgII (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The partitioning of oxidized Hg remains similar to run 2, with HgBrOH being the predominant species throughout the troposphere (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

In summary, although we acknowledge there are uncertainties in current redox kinetics, HgII processing in clouds and aqueous aerosols, and in the Br concentrations, our results imply, within the noted uncertainties, a missing Hg0 oxidation pathway in the troposphere. This Hg oxidation deficit leads to a calculated unrealistically long Hg0 lifetime. Furthermore, implementation of the photoreduction mechanism leads to underestimation of observed HgII wet deposition. These findings demonstrate that further laboratory, field, and modeling research on the atmospheric chemical cycle of Hg is urgently required.

Methods

Description of the GLEMOS Model.

For evaluating the Hg chemical mechanisms under the atmospheric conditions, we apply the three-dimensional multiscale chemical transport model GLEMOS. The model simulates atmospheric transport, chemical transformations, and deposition of Hg species (29, 37). In this study the model grid has a horizontal resolution 3° × 3° and covers troposphere and lower stratosphere up to 10 hPa (∼30 km) with 20 irregular terrain-following sigma layers. The atmospheric transport of the tracers is driven by meteorological fields generated by the Weather Research and Forecast modeling system (WRF) (38) fed by the operational analysis data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (39). In the current version the model treats Hg0, HgBr, HgBr2, HgBrO, HgBrOH, HgBrOOH, HgBrONO, HOHg, HOHgOOH, and HOHgONO as separate species. Gas-particle partitioning of HgII is parametrized following Amos et al. (40). Details of the chemical scheme used in the model are given in SI Appendix, Table S1. Note that direct formation of the BrHgO radical, from the insertion reaction between Hg0 and the BrO radical, was not included in the present mechanism due to the limited experimental and theoretical information available on this reaction (SI Appendix, Supplementary Note 3). Six-hourly concentration fields of Br are archived from a CAM-Chem simulation (41). Concentrations of OH, HO2, NO2, and particulate matter (PM2.5) are imported from MOZART (42). We have also included the gas-phase photoreduction of HgBr, HOHg, HgBr2, HgBrOH, HgBrOOH, HgBrONO, HOHgOOH, and HOHgONO using the photolysis rates calculated by CAM-Chem (20, 21, 43) (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Note 4 for HgBr2), including the photolysis yields determined theoretically by multiconfigurational quantum chemistry (24), and an aqueous-phase photoreduction in cloud droplets with a photolysis rate constant 0.153 h−1. We perform simulations for the period 2007–2013 using anthropogenic Hg emissions for 2010 (1) of 1,875 Mg/y. Prescribed fluxes of natural and secondary Hg0 reemissions from soil and seawater are generated depending on Hg concentration in soil, soil temperature, and solar radiation for emissions from land and proportional to the primary production of organic carbon in seawater for emissions from the ocean (37). Additionally, prompt reemission of Hg from snow is taken into account using an empirical parametrization based on the observational data (44–46). Total net evasion of Hg0 from natural terrestrial and oceanic surfaces varies from 3,050 to 3,200 Mg/y for different tests that is comparable with 3,370 Mg/y of net Hg0 emission estimated by Horowitz et al. (6). The first 6 y of the period are used for the model spin up to achieve steady-state Hg concentrations in the troposphere. The model results are presented as annual averages for 2013.

Hg0 and HgII Observations.

The dataset of ground-based Hg0, HgII, and HgII wet deposition observations used in this study is based on the compilation of observations published in Travnikov et al. (29). It contains observations from the Global Mercury Observation System (GMOS) monitoring network (47, 48), the EMEP regional network (49), the Mercury Deposition Network of the National Atmospheric Deposition Program (50), the Atmospheric Mercury Network (51), and the Canadian National Atmospheric Chemistry Database (52, 53). The dataset includes annual mean measurements of Hg0, HgII, and HgII wet deposition flux in 2013. Geographical location of the measurement sites is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7.

For the dataset of altitudinal HgII variability, we compiled northern hemisphere midlatitude (30-60°N) aircraft HgII data from the literature, with observations made by dual-channel oxidized Hg difference methods (17, 54, 55). Gaseous oxidized HgII observations made by KCl-coated denuder methods (56) were multiplied by 1.56 following ref. (57) for typically observed denuder HgII loss under free tropospheric conditions (55, 57). Gaseous oxidized HgII (loss-corrected) and particulate HgII in the Brooks et al. (56) study were summed to yield total HgII. The unique, but uncalibrated, stratospheric mean HgII observations by Murphy et al. (58) were anchored to the Slemr et al. (59) mean HgII observations for December–May (30–60°N). All available aircraft HgII data were subsequently binned for 1-km altitude levels, and mean and SDs are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S8.

For the dataset of vertical Hg0 distribution, we used data from two simultaneous aircraft measurement campaigns in northern Europe. The European Tropospheric Mercury Experiment (ETMEP) measured vertical profiles of the Hg0 concentration inside the planetary boundary layer and the lower free troposphere in an altitude range of 500–3,500 m (60). The measurements were performed with two collocated Tekran instruments (2537X and 2537B). These were both operated with upstream particle filters and one (2537B) with an additional quartz wool trap to remove oxidized Hg species (54, 61). The experiment was timed in a manner that the data are comparable to observations from the Civil Aircraft for the Regular Investigation of the atmosphere Based on an Instrumented Container project which measured total Hg and Hg0 in altitudes from 6,000–12,000 m using a Tekran 2537A (62, 63).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study has received funding from the European Research Council Executive Agency under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme (Project ERC-2016- COG 726349 CLIMAHAL) and the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO) /Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) (Projects CTQ2017-87054-C2-2-P, RYC-2015-19234, and CEX2019-000919-M). This work was supported by the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) Spain. A.F.-M. acknowledges the Generalitat Valenciana and the European Social Fund (Contract APOSTD/2019/149 and Project GV/2020/226) for the financial support. J.C.-G. acknowledges the Universitat de València for his Masters Scholarship. M.J. acknowledges funding by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant PZ00P2_174101). The ETMEP measurements as well as ground-based measurements of the GMOS network were funded by the EU FP7-ENV-2010 project (GMOS, Grant Agreement 265113). J.S.F. acknowledges the H2020 ERA-PLANET (689443) Integrated Global Observing Systems for Persistent Pollutants (iGOSP) and Integrative and Comprehensive Understanding on Polar Environments (iCUPE) programs.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1922486117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.

Change History

July 26, 2021: The text of this article has been updated; please see accompanying Correction for details.

References

- 1.AMAP/UN, Technical Background Report for the Global Mercury Assessment , “2018. Arctic monitoring assessment programme Oslo, Norway/UN environment programme chemical health branch” (Switz, Geneva, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obrist D., et al., A review of global environmental mercury processes in response to human and natural perturbations: Changes of emissions, climate, and land use. Ambio 47, 116–140 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driscoll C. T., Mason R. P., Chan H. M., Jacob D. J., Pirrone N., Mercury as a global pollutant: Sources, pathways, and effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 4967–4983 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L., et al., A synthesis of research needs for improving the understanding of atmospheric mercury cycling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 9133–9144 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ariya P. A., et al., Mercury physicochemical and biogeochemical transformation in the atmosphere and at atmospheric interfaces: A review and future directions. Chem. Rev. 115, 3760–3802 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horowitz H. M., et al., A new mechanism for atmospheric mercury redox chemistry: Implications for the global mercury budget. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 6353–6371 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Si L., Ariya P. A., Recent advances in atmospheric chemistry of mercury. Atmosphere (Basel) 9, 76 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dibble T. S., Tetu H. L., Jiao Y., Thackray C. P., Jacob D. J., Modeling the OH-initiated oxidation of mercury in the global atmosphere without violating physical laws. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 444–453 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodsite M. E., Plane J. M. C., Skov H., A theoretical study of the oxidation of Hg0 to HgBr2 in the troposphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 1772–1776 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes C. D., Jacob D. J., Yang X., Global lifetime of elemental mercury against oxidation by atomic bromine in the free troposphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L20808 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saiz-Lopez A., von Glasow R., Reactive halogen chemistry in the troposphere. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6448–6472 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson W. R., Brown S. S., Saiz-Lopez A., Thornton J. A., Glasow Rv., Tropospheric halogen chemistry: Sources, cycling, and impacts. Chem. Rev. 115, 4035–4062 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang F., et al., Enhanced production of oxidised mercury over the tropical Pacific Ocean: A key missing oxidation pathway. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 1323–1335 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes C. D., et al., Global atmospheric model for mercury including oxidation by bromine atoms. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 12037–12057 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S., et al., Direct detection of atmospheric atomic bromine leading to mercury and ozone depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 14479–14484 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obrist D., et al., Bromine-induced oxidation of mercury in the mid-latitude atmosphere. Nat. Geosci. 4, 22–26 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gratz L. E., et al., Oxidation of mercury by bromine in the subtropical Pacific free troposphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10,494–10,502 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gencarelli C. N., et al., Sensitivity model study of regional mercury dispersion in the atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 627–643 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pacyna J. M., et al., Current and future levels of mercury atmospheric pollution on a global scale. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 12495–12511 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saiz-Lopez A., et al., Photoreduction of gaseous oxidized mercury changes global atmospheric mercury speciation, transport and deposition. Nat. Commun. 9, 4796 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saiz-Lopez A., et al., Gas-phase photolysis of Hg(I) radical species: A new atmospheric mercury reduction process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8698–8702 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Foy B., et al., First field-based atmospheric observation of the reduction of reactive mercury driven by sunlight. Atmos. Environ. 134, 27–39 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Q., et al., Diel variation in mercury stable isotope ratios records photoreduction of PM2.5-bound mercury. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 315–325 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam K. T., Wilhelmsen C. J., Schwid A. C., Jiao Y., Dibble T. S., Computational study on the photolysis of BrHgONO and the reactions of BrHgO• with CH4, C2H6, NO, and NO2: Implications for formation of Hg(II) compounds in the atmosphere. J. Phys. Chem. A 123, 1637–1647 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francés-Monerris A.et al., Photodissociation mechanisms of major mercury(II) species in the atmospheric chemical cycle of mercury. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7605–7610 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dibble T. S., Zelie M. J., Mao H., Thermodynamics of reactions of ClHg and BrHg radicals with atmospherically abundant free radicals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 10271–10279 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dibble T. S., Schwid A. C., Thermodynamics limits the reactivity of BrHg radical with volatile organic compounds. Chem. Phys. Lett. 659, 289–294 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bieser J., et al., Multi-model study of mercury dispersion in the atmosphere: Vertical and interhemispheric distribution of mercury species. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 6925–6955 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Travnikov O., et al., Multi-model study of mercury dispersion in the atmosphere: Atmospheric processes and model evaluation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 5271–5295 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pal B., Ariya P. A., Studies of ozone initiated reactions of gaseous mercury: Kinetics, product studies, and atmospheric implications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 572–579 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shepler B. C., Peterson K. A., Mercury monoxide: A systematic investigation of its ground electronic state. J. Phys. Chem. A 107, 1783–1787 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hynes A. J., Donohoue D. L., Goodsite M. E., Hedgecock I. M., “Our current understanding of major chemical and physical processes affecting mercury dynamics in the atmosphere and at the air-water/terrestrial interfaces” in Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere: Emissions, Measurements and Models, Mason R., Pirrone N., Eds. (Springer US, 2009), pp. 427–457. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaffe D. A., et al., Progress on understanding atmospheric mercury hampered by uncertain measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7204–7206 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gustin M. S., Dunham-Cheatham S. M., Zhang L., Comparison of 4 methods for measurement of reactive, gaseous oxidized, and particulate bound mercury. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 14489–14495 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu R., Wang C., Dibble T. S., First experimental kinetic study of the atmospherically important reaction of BrHg + NO2. Chem. Phys. Lett. 759, 137928 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khiri D., Louis F., Černušák I., Dibble T. S., BrHgO• + CO: Analogue of OH + CO and reduction Path for Hg(II) in the atmosphere. ACS Earth Space Chem. 4, 1777–1784 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Travnikov O., Ilyin I., “The EMEP/MSC-E mercury modeling system” in Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere, Mason R., Pirrone N., Eds. (Springer, Boston, MA, 2009), pp. 571–587. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skamarock J. G., et al., A description of the advanced research WRF version 2. NCAR Technical Note, NCAR/TN–468+STR. (National Center Atmospheric Research Boulder Co Mesoscale Microscale Meteorology Div, Boulder, Co) (2005).

- 39.European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts , ECMWF operational analysis: Assimilated data. NCAS British Atmospheric Data Centre. http://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/c46248046f6ce34fc7660a36d9b10a71. Accessed 11 November 2020.

- 40.Amos H. M., et al., Gas-particle partitioning of atmospheric Hg(II) and its effect on global mercury deposition. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 591–603 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez R. P., Salawitch R. J., Kinnison D. E., Lamarque J.-F., Saiz-Lopez A., Bromine partitioning in the tropical tropopause layer: Implications for stratospheric injection. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 13391–13410 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emmons L. K., et al., Description and evaluation of the model for ozone and related chemical tracers, version 4 (MOZART-4). Geosci. Model Dev. 3, 43–67 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sitkiewicz S. P., Rivero D., Oliva-Enrich J. M., Saiz-Lopez A., Roca-Sanjuán D., Ab initio quantum-chemical computations of the absorption cross sections of HgX2 and HgXY (X, Y = Cl, Br, and I): Molecules of interest in the Earth’s atmosphere. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 455–467 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirk J. L., St Louis V. L., Sharp M. J., Rapid reduction and reemission of mercury deposited into snowpacks during atmospheric mercury depletion events at churchill, Manitoba, Canada. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 7590–7596 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson K. P., Blum J. D., Keeler G. J., Douglas T. A., Investigation of the deposition and emission of mercury in arctic snow during an atmospheric mercury depletion event. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D17304 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrari C. P., et al., Atmospheric mercury depletion event study in Ny-Alesund (Svalbard) in spring 2005. Deposition and transformation of Hg in surface snow during springtime. Sci. Total Environ. 397, 167–177 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sprovieri F., et al., Atmospheric mercury concentrations observed at ground-based monitoring sites globally distributed in the framework of the GMOS network. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 11915–11935 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sprovieri F., et al., Five-year records of mercury wet deposition flux at GMOS sites in the Northern and Southern hemispheres. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 2689–2708 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tørseth K., et al., Introduction to the European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme (EMEP) and observed atmospheric composition change during 1972-2009. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 5447–5481 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prestbo E. M., Gay D. A., Wet deposition of mercury in the U.S. and Canada, 1996–2005: Results and analysis of the NADP mercury deposition network (MDN). Atmos. Environ. 43, 4223–4233 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gay D. A., et al., The atmospheric mercury network: Measurement and initial examination of an ongoing atmospheric mercury record across North America. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 11339–11349 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cole A. S., et al., Ten-year trends of atmospheric mercury in the high Arctic compared to Canadian sub-Arctic and mid-latitude sites. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 1535–1545 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steffen A., et al., Atmospheric mercury in the Canadian Arctic. Part I: A review of recent field measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 509–510, 3–15 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lyman S. N., Jaffe D. A., Formation and fate of oxidized mercury in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere. Nat. Geosci. 5, 114–117 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swartzendruber P. C., Jaffe D. A., Finley B., Development and first results of an aircraft-based, high time resolution technique for gaseous elemental and reactive (oxidized) gaseous mercury. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 7484–7489 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brooks S., et al., Airborne vertical profiling of mercury speciation near Tullahoma, TN, USA. Atmosphere (Basel) 5, 557–574 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marusczak N., Sonke J. E., Fu X., Jiskra M., Tropospheric GOM at the Pic du Midi observatory-correcting bias in denuder based observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 863–869 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy D. M., Hudson P. K., Thomson D., Sheridan P. J., Wilson J. C., Observations of mercury-containing aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 3163–3167 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slemr F., et al., Mercury distribution in the upper troposphere and lowermost stratosphere according to measurements by the IAGOS-CARIBIC observatory: 2014–2016. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 12329–12343 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weigelt A., et al., Tropospheric mercury vertical profiles between 500 and 10 000 m in central Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 4135–4146 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ambrose J. L., Lyman S. N., Huang J., Gustin M. S., Jaffe D. A., Fast time resolution oxidized mercury measurements during the Reno atmospheric mercury intercomparison experiment (RAMIX). Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 7285–7294 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slemr F., et al., Mercury plumes in the global upper troposphere observed during flights with the CARIBIC observatory from May 2005 until June 2013. Atmosphere (Basel) 5, 342–369 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slemr F., et al., Atmospheric mercury measurements onboard the CARIBIC passenger aircraft. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 9, 2291–2302 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.