ABSTRACT

Background: Recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases have affected members of religious communities. While major religions support vaccines, the views of individual clergy who practice and propagate major faith traditions are unclear. Our objective was to explore clergy attitudes toward vaccines and vaccine advocacy.

Methods: In 2018–2019, we conducted qualitative interviews with clergy in Colorado and North Carolina. We inductively analyzed transcripts using a grounded theory approach, developing codes iteratively, resolving disagreements by consensus, and identifying themes.

Results: We interviewed 16 clergy (1 Buddhist, 3 Catholic, 2 Jewish, 1 Hindu, 1 Islamic, 7 Protestant, and 1 Unity). Analyses yielded seven themes: attitudes toward vaccines, congregational needs, public health climate, perceived responsibility, comfort and competing interests, reported advocacy efforts, and clergy health advocacy goals. Most clergy had positive vaccination attitudes and were open to vaccine advocacy, although discomfort with medical concepts and competing interests in their congregations influenced whether many had chosen to advocate for vaccines. Over half reported promoting vaccination in various contexts.

Conclusions: In our sample, U.S. clergy held complex attitudes toward vaccines, informed by experience and social norms as much as religious beliefs or Scriptures. Clergy may be open to vaccine advocacy, but a perceived lack of relevance in their faith communities or a lack of medical expertise may limit their advocacy efforts in diverse contexts. Amidst growing vaccine hesitancy, pediatricians could partner with clergy in their communities, answer questions about vaccines, raise awareness of recent outbreaks, and empower clergy in joint educational events.

KEYWORDS: Religion, vaccination, vaccines, clergy, advocacy

Introduction

Vaccination is essential to public health, but vaccine hesitancy is an increasing, worldwide threat.1 The U.S. experienced over 1200 cases of measles in 2019; many outbreaks affected religious communities, such as Orthodox Jewish communities in New York.2 To address the mounting public health crisis of vaccine refusal, researchers have suggested novel communication approaches with vaccine-hesitant parents,3 sweeping changes to exemptions to school immunization laws,4 and financial incentives and legal charges to motivate parents to vaccinate.5 However, restoring confidence in vaccination may also require novel public health partnerships to disseminate information about and increase public trust in vaccines.

Religious leaders, or clergy, are community leaders who may strongly influence the health attitudes and habits of their congregations.6 As of 2014, nearly 75% of Americans reported adhering to a religious tradition with formal clergy.7 For nearly a century, public health leaders have recognized that clergy have opportunities to serve as public health advocates.8 Anecdotal reports suggest clergy could be influential advocates for vaccines. During a 2017 measles outbreak associated with vaccine misinformation in a Minnesotan Somali community, Muslim clergy (Imams) partnered with public health workers to increase trust in the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine through joint educational sessions.9 However, few studies of clergy attitudes toward vaccines or vaccine advocacy exist. The only U.S. study of which we are aware – a pilot survey we conducted in Denver, CO – suggested 25% of clergy were vaccine hesitant and only 10% had ever discussed vaccines, all doing so infrequently.10 Furthermore, we did not study determinants of clergy attitudes toward vaccines, identify why few clergy addressed vaccines, or investigate why many others did not. Thus, our objective was to use rigorous qualitative methods to explore clergy attitudes toward vaccines and vaccine advocacy.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study using grounded theory methodology, which is useful for the study of complex processes and generates theoretical understandings of studied experiences.11,12 We recruited participants with a purposeful sampling strategy to ensure representation from five major faith traditions (Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism), divergent vaccination attitudes (Positive, Neutral, and Hesitant), and different geographic locations (Colorado, North Carolina). Then, we pursued theoretical sampling to examine, test, and further develop emerging themes. We continued sampling until we reached thematic saturation. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

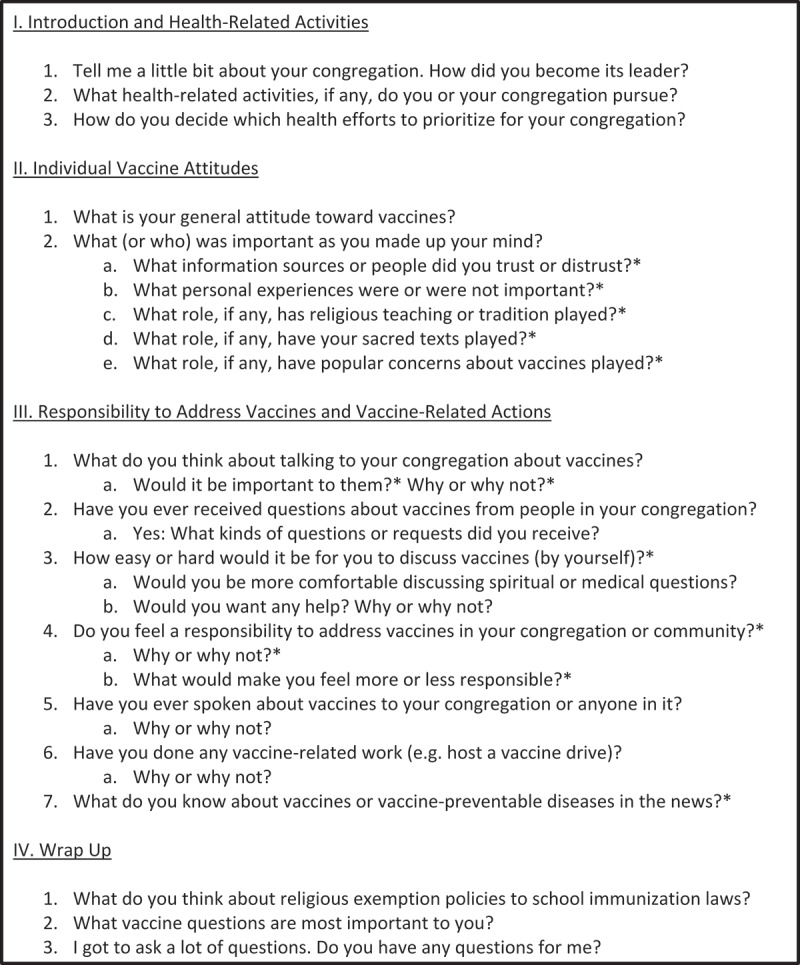

One investigator (JW) created a pool of potential contacts meeting purposeful sampling criteria from an existing contact list of over 100 Denver clergy from a prior quantitative study of clergy attitudes toward vaccines, randomly inviting Colorado clergy thereafter.10 A program administrator at Duke Divinity School e-mailed contacts from the Clergy Health Initiative at random to recruit individuals from North Carolina. We recruited participants by e-mail and phone; contacts received up to three e-mails and three phone calls. Clergy were asked to participate in an individual interview with a male academic pediatrician studying clergy attitudes toward vaccines and vaccine advocacy. Interviews occurred in person from October 2018 to September 2019. Fifteen occurred in clergy offices; one occurred in a reserved room at a library. Clergy provided verbal consent and then completed a brief online survey with demographic questions and a validated vaccine hesitancy questionnaire.13 We chose the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) short scale because it is five items long, correlates with five categories of vaccine acceptance, and is easy to self-administer (Appendix).13 We included the instrument to objectively recruit at least two vaccine-hesitant clergy, in case clergy attitudes toward vaccine advocacy differed by vaccination attitude. Data collection was securely facilitated with REDCap.14 One investigator (JW) conducted all interviews, which averaged 45 minutes, using a semi-structured interview guide developed for this study (Figure 1). We added or modified questions based on concurrent data analysis; questions explored clergy attitudes toward all vaccines, generally. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Figure 1.

Semi-structured interview guide. Questions with an asterisk (*) indicate they were added or revised during the analytic process

We conducted data analysis simultaneously with data collection, according to best practices.12 One investigator (JW) wrote field notes during and memos after each interview, analyzing emerging codes, forming possible thematic categories, and refining the semi-structured interview guide. Then, the same investigator (JW) reviewed all transcripts and developed lists of codes using an iterative approach, modifying and adding codes to best reflect data content. A second doctoral-trained investigator (MF) reviewed a subset of four transcripts and generated coding lists. The two investigators compared codes as a team, organized codes into themes, and resolved discrepancies by consensus. We used HyperRESEARCH 3.0 (Boston, MA) to collate data for our thematic summaries.

In the final analysis, the research team returned to the data to verify relationships within and across themes and construct a theory that arose from the data. We assessed the trustworthiness of our findings through sequential exploration of emerging hypotheses with subsequent clergy participants and reflexive team analysis. One investigator (JW) reviewed final themes, their interpretations, and the grounded theory with three participants from different faith traditions to elicit feedback. All found that the thematic summaries and theory resonated with their perspectives, and one additional insight was included in the final analysis.

Results

We contacted 31 clergy. Two declined due to busyness, and 13 did not return e-mails or phone calls; we interviewed 16 (response rate 52%). Clergy averaged 51 y old (range 32–68), were primarily male (n = 13), spoke English as a first language (n = 15), had children (n = 14), and resided in Colorado (n = 14). Table 1 provides full demographics. Nearly all clergy (14/16) had low vaccine hesitancy scores, although one was moderately hesitant and one was very hesitant. Analyses revealed seven themes and a grounded theory, which related themes to one another. Themes, sub-themes, and representative quotations are presented in the text and in Tables 2 and 3. The final theme, which places clergy advocacy specifically in the context of other clergy health-related advocacy efforts, is summarized in the text alone. To preserve clergy anonymity, especially for clergy from traditions with few congregations in our study areas, we preface individual leaders’ quotations with the generic term “clergy” or “minister” as needed.

Table 1.

Participant clergy demographics (n = 16) and scaled vaccine hesitancy scores (proportions may not add up to 100% due to rounding)

| Demographic characteristic | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| First language | ||

| English | 15 (94) | |

| Spanish | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (6) | |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 1 (6) | |

| Black | 2 (13) | |

| White | 12 (75) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (6) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 14 (88) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (6) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (6) | |

| Education | ||

| High school or GED | 1 (6) | |

| Associate degree | 1 (6) | |

| Master’s degree | 7 (44) | |

| Professional degree | 5 (31) | |

| Doctoral degree | 2 (13) | |

| Clergy role | ||

| Head pastor (or equivalent) | 11 (69) | |

| Associate pastor (or equivalent) | 3 (19) | |

| Other | 2 (13) | |

| Length of service | ||

| Less than 5 y | 1 (6) | |

| 5–10 y | 5 (31) | |

| 11–20 y | 4 (25) | |

| More than 20 y | 6 (38) | |

| Religion | ||

| Buddhism | 1 (6) | |

| Christianity (Catholicism) | 3 (19) | |

| Christianity (Protestantism) | 7 (44) | |

| Hinduism | 1 (6) | |

| Islam | 1 (6) | |

| Judaism | 2 (13) | |

| Unity Churches | 1 (6) | |

| Vaccine hesitancy | ||

| Low (0–4) | 14 (88) | |

| Medium (5–6) | 1 (6) | |

| High (7–10) | 1 (6) | |

Table 2.

Descriptions and determinants of clergy attitudes toward vaccines with representative quotations

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Clergy Attitudes | ● Positive | “We have different strains of the flu every year. We’ve got to be careful. For the tradeoff of what happens to the body to help build the resistance, it counts as one of the modern miracles.” |

| ● Unsure | “I think if I was a parent of a young child today, I would probably read closer to see which ones were required. I’m not sure I would take all of the optional things offered.” | |

| ● Negative | “I do have some resistance to vaccines, but not from a religious standpoint so much.” | |

| Factors Informing Clergy Attitudes toward Vaccines | ● Reason | “I trusted my pediatrician’s advice. My pediatrician also happened to be Buddhist – a Zen Buddhist. […] I did have a lot of trust in her, because I knew that we had a similar view of the world and the spiritual aspect of life. So, yea, I trusted her quite a bit.” |

| “We are flawed, and so we don’t always make the right vaccine for the right situation. […] Take the flu – I know there have been years when they thought they had the right vaccine and then it wasn’t the right one for the flu that hit that year. But that’s just the nature of our knowledge.” | ||

| ● Experiences | “Recently, I was supposed to get a shot for pneumonia. And I said, ‘I’m not going to get pneumonia. I’ll put it off.’ I said, ‘I’ll do that later.’ And then I got pneumonia! So, I’m going to be getting the shot! I’m not going to make that mistake again. That pneumonia is no joke!” | |

| ● Sacred Texts | “‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ Insofar as vaccines help the general population stay immune, I think that would be a key [verse]. Other than that, it’s pretty hard to come up with texts that I would say, ‘That really speaks to vaccines.’” | |

| ● Religious Beliefs | “I don’t know what religious concerns could be present for vaccines! […] As a Protestant person, I’m not aware of any arguments that have been made. I don’t know how one does that.” | |

| “There’s a public health component of a Jewish mindset. […] An acknowledgement that sickness can impact the rest of the community. I don’t know if we own that Jewishly, but it feels Jewish to me.” | ||

| “I think you are fine to take [vaccines] because life is precious. Life needs to be saved. Then, the process of circularization will go on. […] Hinduism sees that life is precious, and it should be saved so that the person who is born is given the opportunity to have the self-realization.” | ||

| ● Social Norms | “Many people in [my community] are very against vaccines – they do believe that they can be as harmful as they can be helpful. I’ve heard people say that there is evidence that they contribute to autism.” |

Table 3.

Descriptions of themes pertaining to congregational vaccine needs, public health climate, perceived responsibility to address vaccines, comfort and competing interests, and reported advocacy efforts, with sub-themes and representative quotations

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Congregational vaccine needs |

|

“I have been [asked], but I feel like I’m being asked as a parent, and not as a pastor. ‘What did you and your wife do about vaccines?’ Not, ‘Pastor, what does the church think about [vaccines]?’” “I sort of assume they’re down with vaccines, that they listen to their doctors. I might be surprised if we were to poll, to do the research here, that there are probably more anti–vaccine people here.” |

| Public health climate |

|

“Recent news has taken place in the Jewish community in Brooklyn. Interestingly, I heard there was a connection to Israel. I think they traced this recent [measles] outbreak in Brooklyn to Israel.” “There is generally a break down in our society’s sense that we’re in this together. And that’s a problem for religion, civic leaders broadly, and clergy – to rebuild a sense of social solidarity.” “For us [African-Americans], there’s always the nascent – with those kinds of questions – trust in the government piece […] There’s collective memory around the syphilis study and various other things.” |

| Perceived responsibility |

|

“I had not considered it as a responsibility until this conversation, because if I had, I would have said, ‘I’m sure there is a responsibility.’ And I would have thought, ‘I need to follow through on it.’” “It’s terrible to say this, but if I knew one of our kids – one of our babies – got infected with the measles right now, it would be a big issue […] It’s unfortunate, but that would be the thing.” “No, actually. I have to have some grip about the subject, and I don’t still. So if I don’t have the grip, even to some extent, then I don’t have any resolve in my mind that I need to talk to my people.” |

| Comfort and competing interests |

|

“I’m not going to give any false information or volunteer information I don’t know. […] I would want to get people who have their expertise in that particular area to see what they say.” “Increasingly, we’ve tried to narrow our focus over the last 10 years, instead of diluting the many things we could be doing and giving $500 here, $250 here, 3 hours to this, and 7 hours to that.” |

| Reported advocacy efforts |

|

“There’s a member of the congregation that I know, and she asked if I would write a letter to her employer […] I support her and her endeavors to be a person of faith. So that’s how I worded it.” “We have video boards at both entrances to the church, we usually make announcements after every mass starting about 3 weeks before [our congregational influenza vaccine drive], we put it in our bulletin, and then we also have an e-mail newsletter that goes out weekly.” “There was a time, in fact, over my first 5 years here as a pastor, that it was important for us to offer the opportunity to the community to come and have the flu shot, right here in the building.” |

A theory of clergy engagement in vaccine advocacy

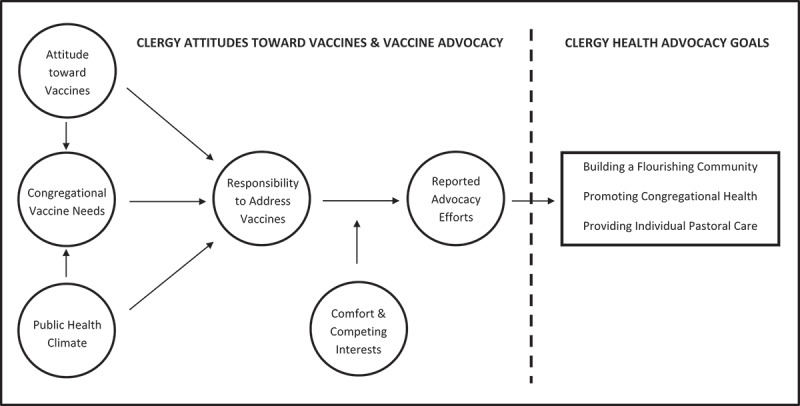

Figure 2 depicts the themes which arose from our analyses and illustrates how clergy attitudes toward vaccines, congregational vaccination needs, and a public health climate inform each other and clergy perceived responsibilities to address vaccines. Comfort with spiritual concepts, discomfort with medical concepts, and competing interests affect whether clergy ultimately advocate for vaccines. Clergy advocacy at individual, congregational, or community levels fits into a larger framework for health advocacy in which clergy provide individual pastoral care, promote holistic congregational health, and build flourishing communities.

Figure 2.

Grounded theory figure describing how clergy vaccine attitudes, perceived responsibility to address vaccines, and reported vaccine-related advocacy inform one another and work toward clergy health-related goals

Clergy attitudes toward vaccines

Most clergy view vaccines positively, although a range of perspectives exists

Most clergy viewed vaccines positively, noting their benefits to child and community health. As one clergyman summarized, “[Vaccines] are super important and have done a lot of good to reduce disease and illness. I’m very positive on vaccines.” Some clergy specifically viewed vaccines as a miraculous gift from God or a spiritual good. As one clergyman exclaimed, “[Vaccination] is a miracle! You know? It wasn’t too long ago that millions of people died because there were no vaccines.” Another religious leader agreed, referring to vaccines as “skillful means: tools that we use to do the right thing or to live a good life.” However, several clergy felt unsure about vaccines. One clergyman said, “I would assume [vaccines] are good things – they help us health-wise. But, I haven’t really thought too much about it.” Another from a different tradition felt similarly uncertain: “I want people to get the benefits of shots. At the same time, if there is a problem [with vaccines], I don’t want them to go through that. So, I’m not sure.” Two clergy endorsed negative attitudes toward vaccines, both distrusting the influenza vaccine for secular reasons. As one said, “I don’t know what’s in it. Why would I want to put that in my body, when I don’t really know what’s in it?”

Reason, experience, sacred texts, religious beliefs, and social norms inform clergy attitudes

Clergy described five authoritative sources that informed their attitudes toward vaccines: reason (i.e., knowledge), experiences, sacred texts, religious beliefs, and social norms. One minister provided this framework: “We hold Scripture, tradition, experience, and reason in relationship with one another. That all of them are supposed to inform [any decision].” A second added the concept of social norms, describing how “the other side to [those four sources] is cultural. Kind of – you know – things people see in the media, things people see on social media.” No clergyperson described using every source; most relied on just two or three. As per reason, all clergy trusted physicians – especially those within their own religious tradition – to provide accurate information about vaccines. All clergy trusted science, but two clergy who were not vaccine hesitant mentioned limitations to human wisdom. Some distrusted the motives of government or pharmaceutical companies. Clergy experiences with vaccines as patients and as parents were especially important. All clergy remembered their own experiences with vaccines as children. Parents discussed how making decisions about vaccines for their children caused them to thoroughly research them. Many clergy noted that sacred texts do not address vaccines, although most believed themes from their sacred texts – such as “Love your neighbor as yourself” – applied to vaccination. Clergy did not identify any religious beliefs prohibiting vaccination. Instead, most emphasized religious beliefs highlighting the preservation of life and importance of community. Finally, many clergy cited social norms about refusing vaccines due to rumors they are linked to autism or that the influenza vaccine causes influenza. As one minister reported, “There definitely are the conceptual ideas of, ‘Well, I got the flu shot and I definitely got sick.’” However, few clergy acted in agreement with these norms or based their attitudes toward vaccines on them; most disavowed them.

Congregational vaccine needs: clergy assumptions and explicit congregational requests

Clergy described a two-pronged approach to discerning the vaccine-related needs of their congregations: explicit requests from congregants and perceptions of their congregations’ needs. As a clergyman explained, “You get a lot of action on certain issues and you have to listen to the people. But then, there are certain things that come up, and it doesn’t matter what they’re telling me they want or need, they elected me to give a broader view.” Most clergy said they had never received explicit questions about vaccines or requests to discuss them, and most assumed their congregations were pro-vaccine. As a minister described, “The push comes from the bottom, to push me forward so that I am out front with those things that the community is saying, ‘we need.’ The other things have to deal with where my church role has led me to be forward, and I don’t know that vaccinations have risen to that point on either side.” Only one participant described explicit requests for access to vaccines; his aging congregation requested a yearly influenza vaccine drive for the sake of convenience.

Public health climate: awareness of measles outbreaks and increasing social isolation

Nearly all clergy were aware of news reports related to vaccines, vaccine-preventable diseases, or proposed vaccine policy changes. As a clergywoman stated, “Obviously, I’m aware of the measles outbreak – that it’s endangering peoples’ lives.” Some noted how our interview request increased their awareness of vaccine-related news. “Your presence here today,” said one minister, “has made me step up and pay a little more attention to the news headlines and the 20 states that are having anti–vaxx laws put forward. And I’m like, ‘Holy Cow!’” Many clergy believed that increasing social isolation and an emphasis on the strong right of the individual – instead of mutual responsibility for one another – had contributed to a public health climate in which vaccine refusal was increasing. Two African-American religious leaders also wondered if wariness with the government and the medical establishment contributed to distrust in vaccines, alluding to historical instances of exploitation.

Perceived responsibility to address vaccines: a conditional threshold to surpass

Clergy described a conditional responsibility to address vaccines, based on their own attitudes toward vaccines, explicit or assumed congregational needs, and the public health climate. Thus, an assurance of vaccines’ harms or benefits, clear congregational needs, and/or public health crises could increase their perceived responsibility to address vaccines to an actionable level. For example, two ministers who had positive attitudes toward vaccines and were acutely aware of measles outbreaks described a strong perceived responsibility to address vaccines. Conversely, several clergy felt no responsibility to address vaccines because of a “sense that people [in their congregations] do it.” Yet, most clergy had nuanced positions. As one leader mentioned, “If I was educated enough and I really believed it was not in the best interests of people, I might speak to that.” Another thought, “if I heard that there were people thinking, ‘Oh, I shouldn’t vaccinate my kids,’ that would be different. Then I would feel like, ‘Yea, we should have that conversation at some level.’” A third mentioned how “[news reports about measles outbreaks] give me some pause to think it’s worth addressing.”

Comfort and competing interests: factors that transform responsibility into advocacy

Comfort with spiritual concepts and discomfort with medical questions

For those clergy with a perceived responsibility to address vaccines, comfort with concepts and competing interests affected whether their responsibility translated into advocacy. Most clergy felt comfortable addressing spiritual or ethical concepts related to public health. Yet, all clergy were uncomfortable with the idea of entertaining medical questions about vaccines. As one clergyman noted, “Talking about the ethical part would be fairly easy, but I feel like I’m not well-equipped to address the medical.” Another cautioned, “[Vaccination] is an area that I have to be careful with because it’s not my expertise. […] It’s not that I wouldn’t speak to it. But, I’d want to bring in experts who know what they are doing to speak to it.”

Competing interests: desiring to do a few things well

Clergy desired to avoid diluting the health activities they engaged in, emphasizing a need to prioritize vaccine advocacy with competing interests for their congregation’s time or money. “We try to pick a few things and do them well,” said one clergyman. “Sometimes,” said another, “it’s just about responding to needs in the moment. I can set my goals all I want, but if we have a lot of people in the hospital or people dying then that’s going to go on the backburner.” Two clergy noted how the availability of vaccines at local supermarkets moved the idea of vaccine drives lower on their priority lists.

Reported actions: advocating for vaccines at individual, congregational, and community levels

Over half of clergy reported advocating for vaccines at individual, congregational, or community levels. Most often, clergy who acted at individual levels reported speaking with concerned congregants one-on-one. “I have a good friend who is a pediatrician,” said one leader, “and he’s just livid over [the increase in vaccine refusal]. He’s a good friend, and we’ve talked.” Another clergywoman described talking with a nurse in her congregation before writing a religious exemption letter for her to work without the influenza vaccine. Noting that her religion does not object to vaccines, the clergywoman still agreed to write the letter in order to support her congregant so that she could remain employed during the winter. Other clergy reported activities at the congregational level, such as a yearly influenza vaccine drive. Most clergy had never spoken about vaccines from the pulpit, but one had advocated for them publicly: “I’ve never preached a sermon that had the topic ‘To vaccinate or not’ or anything like that. But, it was part of a sermon series I did on science and faith.” At the community level, three clergy had coordinated influenza vaccine drives in their neighborhoods, one with a local department of public health. Two clergy described enforcing immunization laws for preschools and daycares. One minister worked at a religious camp that enforced a strict vaccination policy.

Clergy health-related advocacy: providing individual pastoral care, promoting congregational health, and building flourishing communities

All clergy viewed health as “part of our whole being. It’s mental health, it’s physical health; it’s all those kinds of things and self-care.” In this context, clergy described routine health advocacy efforts at three levels: individual, congregational, and community. At the individual level, clergy sought to provide personalized pastoral care, attending to specific needs. Most clergy cited the importance of visiting congregants in the hospital and praying with them. At the congregational level, clergy hired health nurses to screen congregants for hypertension or diabetes, formed grief or divorce groups to facilitate connection, or discussed healthy eating or other mental illness from the pulpit. At the community level, clergy reported participating in social justice initiatives, lobbying their congressperson to repeal the death penalty, funding subsidized housing, or growing fresh fruits and vegetables for their neighborhoods. “Flourishing,” envisioned one leader, “That’s where we want to get to.” Another declared, “I’m not appointed by the bishop to serve this church. I’m appointed by the bishop to serve the people of [my city]. […] It is my job to help this church serve the community.”

Discussion

We present the first qualitative study of American clergy attitudes toward vaccines and vaccine advocacy. In our study, most clergy viewed vaccines positively, were open to the idea of vaccine advocacy, and desired help from experts to address vaccines in local settings.

First, we provide detailed descriptions of American clergy attitudes toward vaccines, showing that clergy attitudes are complex and do not simply align with theological literature. Historically, with the exclusion of minor sects within Christianity (e.g., Christian Science, Dutch Orthodox Reformed Church), all major religions have supported vaccination.15 Yet, over 60 outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases have affected U.S. religious communities in the last few decades.15 While major religions support vaccines in principle, our study shows that religious leaders within supportive traditions often hold nuanced positions in practice. Without explicit scriptural references to vaccines and unaware of any official teachings regarding them, most clergy in our study relied on personal experience, social norms, and various information sources to form attitudes about vaccines. Thus, while most clergy in our study formed positive attitudes toward vaccines, several formed neutral or even negative attitudes, and none were from religious traditions that historically reject vaccines. Importantly, clergy who share negative attitudes with congregants can increase the risk of vaccine-preventable diseases in their houses of worship. In recent years, measles outbreaks in Jewish synagogues in New York and at a Christian church in Texas have been linked to individual clergy who disparaged vaccines.2,10

Our findings about clergy attitudes to vaccines also inform results from a prior survey of clergy attitudes toward vaccines, which noted hesitancy in a number of Catholic priests.10 The finding was surprising, as Catholicism strongly supports vaccines and has published a statement in their defense.16 Yet, our qualitative insights suggest that clergy without children may lack formative parental experiences with vaccines and thus rely on social norms or other information sources to assess their safety or efficacy. To address such discrepancies, religious organizations could craft and publicize policy statements intended for clergy specifically. Such engagement could educate religious leaders without formative parental experiences; it may also cause vaccine-hesitant clergy to reconsider their attitudes toward vaccines. Such engagement may create public health benefits. In 2014, the Catholic bishop of Orlando, FL, relied on a moral analysis by the Pontifical Academy for Life and National Catholic Bioethics Center to decide that the diocese of Orlando would no longer accept religious exemptions for students at Catholic schools.17 Future work should assess the impact of such decisions by influential clergy on public health in their communities.

Next, while nearly all our participants espoused positive views of vaccines, we show that positive attitudes toward vaccines do not immediately translate into advocacy. Rather, in our study, even clergy who viewed vaccines as divine gifts adopted cautionary approaches to advocating for them, wanting public health crises or perceived congregational needs to cue them to action. This finding may help explain why many clergy do not advocate for vaccines until outbreaks occur. For example, New York clergy championed vaccines in local media outlets in the spring of 2019, yet only after measles entrenched itself in Jewish communities.18 Likewise, Denver Marshallese clergy helped coordinate a vaccination campaign against mumps in 2017, only after mumps had infected multiple members of the same church.19 Conditional responsibility could also clarify why only 10% of clergy reported addressing vaccines in their congregations in a prior survey of religious leaders.10 Perhaps, the majority did not perceive a responsibility to do so, and those who felt responsible may have been deterred from acting by discomfort with medical concepts or competing health-related priorities. Finally, the concept of conditional responsibility may clarify findings from a small, qualitative study of 12 Dutch clergy from the Dutch Orthodox Reformed Church. In this study, the three clergy who did not advocate for vaccines had positive vaccine attitudes, believed their congregations were pro-vaccine, and reported rarely receiving questions about vaccines.20 Conversely, the five clergy who preached against vaccines had strong, negative attitudes toward them and perceived a clear duty to educate their congregants.20 Interestingly, no clergy advocated for vaccines in the Dutch sample; conversely, in our American sample, over half had advocated for vaccines in various contexts, and one had actively preached positively about them from the pulpit.

Finally, we unearth a possible advocacy opportunity for physicians and public health professionals. In our study, clergy highly trusted physicians for vaccine information and described a superior trust in physicians within their own religion. Studies estimate about half of U.S. physicians are religious,21 and compared with the general population, physicians are more likely to be affiliated with underrepresented faith traditions, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Mormonism.22 Thus, religious physicians may have a unique advocacy opportunity in their own churches, mosques, or temples. Furthermore, those who are not religious may be uniquely trusted as community leaders and welcomed into local houses of worship. Pediatricians could answer clergy questions about vaccines, request that clergy address them, and promote awareness of recent disease outbreaks. Such efforts may cue clergy with a perceived responsibility to action. To further assist clergy, physicians or health workers could agree to partner with them to address medical questions about vaccines at joint educational events. Such partnerships helped stop measles in Minnesota,9 but they may also work well in primary prevention. For example, clergy–health pairs could speak about childhood vaccines each summer before school begins or influenza vaccination each October before winter arrives. Community-based participatory research is underway to determine the preferred timing, format, and content of such events.23

This study has several strengths, including its sentinel description of clergy attitudes toward vaccines and vaccine advocacy in a sample of interfaith leaders during a time of measles outbreaks in several U.S. religious communities. It also has several limitations, including its small sample size for qualitative studies. Although we achieved saturation with our transcripts, we recruited a limited number of non-Christian clergy, and additional themes may emerge in studies of non-Christian clergy only. We also recruited few vaccine-hesitant clergy, and our sample did not include clergy who objected to vaccines on religious grounds. However, we believe our framework for clergy vaccine attitude determinants – reason, experience, sacred texts, and religious beliefs – can still illuminate how clergy with vaccine concerns related to sacred texts or religious traditions would weigh those concerns against reason and personal experience to form a personal attitude toward vaccines. Our results may not be transferable to clergy who work in rural settings, do not speak English, or have non-English-speaking congregations. Finally, while our findings were consistent in interviews with a small number of clergy in North Carolina, research is needed to determine the extent to which our model applies more broadly.

Conclusions

Amidst growing vaccine skepticism, clergy may be powerful vaccination advocates in need of cues to action from physicians and public health professionals. Future work must optimize and evaluate clergy and health-professional vaccination partnerships, especially for clergy who work with high numbers of vaccine-hesitant congregants. History suggests such alliances can be fruitful. In the 19th century England, Dr. Edward Jenner spoke to Reverend Rowland Hill about smallpox vaccination, and Hill’s later vaccination campaigns contributed to the eradication of smallpox in the British Isles.24 Today, such dialogue may be similarly influential as pediatricians work to counter vaccine skepticism in America.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work of Adrian Miller, JD, and Carl Weisner, who provided contacts for and supported our recruitment efforts.

Appendix.

Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) short form questions with response options. Answers of “Yes/Hesitant” receive 2 points, answers of “No/Not Hesitant” receive 0 points, and answers of “Don’t know/Not sure” receive 1 point. Scores are summed, creating a raw total. Vaccine hesitancy status is defined using the raw sum, with “Low” (0–4), “Medium” (5–6), and “High” (7–10) categories.

- I trust the information I receive about shots.

- Yes

- No

- Don’t know

- It is better for children to develop immunity by getting sick than to get a shot.

- Yes

- No

- Don’t know

- It is better for children to get fewer shots at the same time.

- Yes

- No

- Don’t know

- Children get more shots than are good for them.

- Yes

- No

- Don’t know

- Overall, how hesitant about childhood shots would you consider yourself to be?

- Hesitant

- Not hesitant

- Not sure

Funding Statement

This work was supported by unrestricted primary care fellowship funds from Denver Health Medical Center’s Departments of Pediatrics, Internal Medicine, and Family Medicine. REDCap data capture was supported by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR025780.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Ten threats to global health in 2019. [accessed 2019. November 7]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- 2.Patel M, Lee AD, Clemmons NS, Redd SB, Poser S, Blog D, Zucker JR, Leung J, Link-Gelles R, Pham H, et al. National update on measles cases and outbreaks – United States, January 1 – October 1, 2019. MMWR. 2019;68(40):893–96. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6840e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, Heritage J, DeVere V, Salas HS, Zhou C, Taylor JA.. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. AJPH. 2015;105(10):1998–2004. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gostin LO, Ratzan SC, Bloom BR. Safe vaccinations for a healthy nation: increasing US vaccine coverage through law, science, and communication. JAMA. 2019;321(20):1969–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weithorn LA, Reiss DR. Legal approaches to promoting parental compliance with childhood immunization recommendations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1610–17. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1423929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anshel MH, Smith M. The role of religious leaders in promoting healthy habits in religious institutions. J Relig Health. 2014;53(4):1046–59. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Research Center . America’s changing religious landscape. [accessed 2019. November 7]. https://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religiouslandscape/.

- 8.Ravenel RP, Calver HN, Young CC, Dublin LI, Hayhurst ER, Clark T, Wolman A, Redfield HW, Tomalin A, Tobey JA, et al. The clergy and public health. AJPH. 1925. September; 15(9):788–89. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall V, Banerjee E, Kenyon C, Strain A, Griffith J, Como-Sabetti K, Heath J, Bahta L, Martin K, McMahon M, et al. Measles outbreak – Minnesota, April–May 2017. MMWR. 2017;66(26):713–17. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6627a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JTB, O’Leary ST. Denver religious leaders’ vaccine attitudes, practices, and congregational experiences. J Relig Health. 2019;58(4):1356–67. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00800-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oladejo O, Allen K, Amin A, Frew PM, Bednarczyk RA, Omer SB. Comparative analysis of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) short scale and the five categories of vaccine acceptance identified by Gust et al. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):4964–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabenstein JD. What the world’s religions teach, applied to vaccines and immune globulins. Vaccine. 2013;31(16):2011–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pontifical Academy for Life . Moral reflections on vaccines prepared from cells derived from aborted human fetuses. National Catholic Bioethics Q. 2006;6:541–48. doi: 10.5840/ncbq20066334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noonan J. Immunization of students enrolling in catholic schools of the diocese of Orlando. [accessed 2019. November 7]. https://www.orlandodiocese.org/ministries-offices/schools/schools-parent-information/schools-immunization-policy/.

- 18.McNeil DG Jr. Religious objections to the measles vaccine? Get the shots, faith leaders say. The New York Times. 2019. April 26.

- 19.Marx GE, Burakoff A, Barnes M, Hite D, Metz A, Miller K, Davizon ES, Chase J, McDonald C, McClean M, et al. Mumps outbreak in a marshallese community – Denver Metropolitan Area, Colorado, 2016–2017. MMWR. 2018;67(41):1143–46. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruijs WL, Hautvast JL, Kerrar S, van der Velden K, Hulscher ME. The role of religious leaders in promoting acceptance of vaccination within a minority group: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2013;28(13):511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson KA, Cheng MR, Hansen PD, Gray RJ. Religious and spiritual beliefs of physicians. J Relig Health. 2017;56(1):205–25. doi: 10.1007/s10943-016-0233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curlin FA, Lantos JD, Roach CJ, Sellergren SA, Chin MH. Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):629–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams JTB, Nussbaum AM, O’Leary ST. Building trust: clergy and the call to eliminate religious exemptions. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):pii: e20190933. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams JTB, Nussbaum AM. Reverend Rowland Hill and a role for religious leaders in vaccine promotion. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(5):697–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- World Health Organization . Ten threats to global health in 2019. [accessed 2019. November 7]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.