Abstract

With the growing demand for internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT), this pragmatic factorial (2 × 2 × 2) randomized controlled trial evaluated strategies for facilitating iCBT engagement and outcomes in routine care. Specifically, the benefits to patients and therapists of using homework reflection questionnaires and offering patients twice-weekly therapist support were examined. Patients (n = 632) accepted into iCBT for depression and/or anxiety were randomly assigned to complete homework reflection questionnaires or not (factor 1), receive once- or twice-weekly support (factor 2), and to receive care from therapists employed in one of two settings (iCBT clinic or a community mental health clinic; factor 3). Outcomes were measured at pre-treatment, and 8, 12, and 24-weeks post-enrollment. Therapist time was tracked and a focus group was conducted to examine therapist experiences. No differences in patient outcomes were found between therapists employed in the two settings; as such, these two groups were combined for further analyses. In terms of engagement, homework reflection questionnaires were associated with fewer website log-ins and days accessing iCBT; twice-weekly support was associated with more patient emails sent to therapists. Despite engagement differences, homework reflection questionnaires and twice-weekly support did not significantly impact primary outcomes; all groups showed large improvements in depression and anxiety that were maintained at 24-week follow-up. Therapists perceived a number of benefits and challenges associated with responding to homework reflection questionnaires and offering twice-weekly support; most notably the strategies did not benefit all patients. Twice-weekly support was associated with increased therapist time and organizational challenges. It is concluded that neither completion of homework questionnaires nor offering twice-weekly support significantly improve iCBT in routine care.

Keywords: Internet-delivered; Cognitive behaviour therapy; Therapist support, homework

Highlights

-

•

Randomized controlled factorial trial of internet-delivered CBT in routine care.

-

•

Examined homework questionnaires (yes/no) and therapist support (once/twice-weekly).

-

•

Homework questionnaires were associated with fewer log-ins and days in treatment.

-

•

Providing twice-weekly therapist support resulted in patients sending more emails.

-

•

Regardless of treatment approach patients reported significant symptom improvements.

1. Introduction

Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) represents an efficacious treatment approach that may reduce several challenges patients encounter when accessing face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), such as barriers related to time, location, stigma, and preference to self-manage symptoms (Andersson et al., 2019). During iCBT, patients access weekly online lessons typically consisting of text and visual materials that teach CBT strategies. In routine care, these lessons are most often offered with some degree of therapist support, such as weekly phone calls or emails (Titov et al., 2019). There is now a large body of research demonstrating that iCBT, especially when offered with therapist support, results in moderate to large effects for various mental health symptoms, such as depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic, social anxiety, and posttraumatic stress (e.g., Andersson et al., 2019; Etzelmueller et al., 2020; Romijn et al., 2019).

With growing interest in offering iCBT in routine care, there is a corresponding interest in research that facilitates implementation efforts and uncovers the conditions under which iCBT is more or less effective (Titov et al., 2018, Titov et al., 2019). Consistent with a pragmatic trial, which focuses on testing interventions in broad routine clinical practice (Pastopoulos, 2011), the purpose of the current study was to advance knowledge about how to optimally deliver therapist support in the routine delivery of iCBT. We were specifically interested in exploring whether patient engagement and outcomes would be improved by having patients complete homework reflection questionnaires (HWRQ) at the beginning of each lesson compared to no questionnaires (NHWRQ). Furthermore, we were interested in the benefits associated with twice-weekly (2W) versus once-weekly (1W) therapist support. The rationale for exploring these two factors is elaborated on below.

Examination of these two factors in routine practice is consistent with the Efficiency Model of Support (Schueller et al., 2017), which suggests that decisions related to whether and how therapist support is offered need to take into account the relative benefits versus costs and challenges of offering therapist support. The model highlights that therapist time is finite and ultimately it is most important to ensure that support is available when patients face challenges in usability, engagement, fit, knowledge or implementation of interventions. The model recommends employing practices that have the greatest impact on outcome and eliminating practices that do not enhance benefit. In this study, we sought to determine whether use of HWRQs and 2W support provide benefit to patients and or therapists.

1.1. Homework reflection questionnaires

In face-to-face CBT, assignment and review of homework (HW) by therapists is fundamental to treatment (Kazantzis et al., 2016). HW refers to “planned activities the patient carries out between sessions, selected together with the therapist, in order to progress toward therapy goals” (Kazantzis et al., n.d.). Review of HW by therapists at the beginning of each lesson is strongly recommended and is associated with an increased likelihood that patients complete HW (e.g., Bryant et al., 1999). In reviewing HW, it is recommended that therapists seek to understand the acquisition of skills, including benefits that patients' experience and challenges patients face when using skills (Kazantzis and L'Abate, 2007). Quality of HW practice is a particularly important predictor of outcome (Kazantzis et al., 2017), although quantity of HW also predicts patient outcomes (Kazantzis et al., 2016).

In the case of iCBT, consistent with face-to-face CBT, patients are typically assigned HW activities to complete between online lessons to facilitate learning of CBT skills (Andersson, 2016). There are some notable differences between HW in iCBT and face-to-face CBT. First, in iCBT, all lesson materials are presented online and in essence represent HW. Second, HW is not selected together with a therapist or ideographically designed, but instead is generically outlined for patients in lesson materials and then adapted by the patient, and acted or not acted upon. Qualitative interviews with patients who have completed iCBT suggest some patients are best categorized as readers of materials, others as doers of activities, and still others as “strivers” or individuals who complete activities, but express ambivalence and or skepticism about benefits (Bendelin et al., 2011).

Therapist review of patient activities in iCBT is accomplished a number of ways. In some programs, patients systematically complete online questionnaires related to the completion of HW and therapists subsequently review and comment on the questionnaires (Andersson, 2016). In other programs, therapists rely on patient emails to understand how patients respond to the lesson/HW (e.g., Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016) with the later discussion dependent on what patients share in terms of usage, benefits and challenges related to CBT skills. Actual discussion of HW in patient emails comprises only a small proportion of email content (Soucy et al., 2019). To our knowledge, the benefit for both patients and therapists of a more systematic approach to gathering information using HWRQ has not been investigated. It is possible that use of HWRQ could address patient (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2018a) and therapist (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017a) concerns that iCBT can feel impersonal, which, in turn, could impact patient engagement and outcomes as well as therapist work experiences. The inclusion of HWRQ may also facilitate learning new cognitive and behavioural skills, which we propose are key mechanisms of psychological health. A comparison of HWRQ and NHWRQ could inform delivery of iCBT in routine care.

1.2. 1W or 2W therapist support

While there has been considerable research comparing iCBT with or without therapist support (Baumeister et al., 2014), there has been less research exploring the optimal amount of support that should be available in iCBT. In our past research, we compared 1W support to support that was only offered when patients requested support. In that case, the optional support was found to result in lower completion rates than 1W support, although patient outcomes were still comparable (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017b). Recently, we examined whether 1W support supplemented with responding to patient emails in one-business-day conferred benefits over 1W support alone (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2020). No significant differences in patient engagement or outcomes were identified when patients were offered additional support. In terms of therapist experiences, however, combining 1W support with therapist response to patient emails in one-business-day was identified as being more satisfying for therapists to deliver in terms of building a relationship with patients. Nevertheless, it was also associated with increased therapist time (155 vs. 109 min of therapist time over 8 weeks) and often resulted in therapists reporting they felt rushed and produced lower quality emails. Therapists subsequently expressed a strong interest in offering 2W support perceiving this would allow them to be more responsive to patient concerns, but would not be as challenging to manage their time. Building on therapists' recommendation, in the current study, we explored the relative benefits for both patients and therapists of offering 2W versus 1W support. Comparison of 1W versus 2W email is also of interest as, similar to HWRQ, it could address patient (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2018a) and therapist concerns that iCBT can feel impersonal (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017a). Furthermore, there is some recent face-to-face literature showing that in the case of depression, 2W support appears to result in greater symptom improvement than 1W support (Bruijniks et al., 2020).

1.3. Study purpose

The purpose of this factorial randomized controlled trial was to contribute to pragmatic knowledge of iCBT in routine practice by examining the benefits of: 1) having patients complete HWRQ versus NHWRQ at the beginning of each lesson related to the previous lesson (e.g., HW effort, understanding, difficulties, and helpfulness); 2) offering 2W versus 1W therapist support; and 3) the interaction between HWRQ/NHWRQ and 1W/2W support. Reflecting the local environment, iCBT was delivered by therapists employed in either an iCBT clinic (iCBT is the only form of care offered) or a community mental health clinic (face-to-face care is the primary focus of this setting and iCBT is a secondary service). In both settings, therapists' workload primarily focused on delivery of iCBT. Groups were compared in terms of patient engagement with iCBT (e.g., lessons completed, emails, log-ins), treatment experiences with iCBT at 8-weeks post-treatment (e.g., treatment satisfaction, therapist alliance, negative effects), and symptom improvement (primary outcomes were depression and generalized anxiety) at 8, 12, 24-weeks post-enrollment. Consistent with implementation research (Hermes et al., 2019), we tracked therapist time required to offer support and explored therapist/supervisor experiences with the HWRQs and 2W support using focus groups/interviews. Understanding therapist experiences is critical in routine care as implementation challenges have significant potential to impact uptake and outcomes of iCBT (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017a; Folker et al., 2018).

It was hypothesized that patients who completed HWRQs and received 2W support would have higher levels of engagement, experience greater reductions in symptoms, and report more positive treatment experiences. Specifically, extrapolating from the Efficiency Model of Support (Schueller et al., 2017), it was predicted that HWRQ and 2W support would maximize the likelihood that support would be available when patients faced challenges and thus improve outcomes. Therapists were expected to have more positive experiences with the HWRQ condition and 2W support as these approaches have potential to overcome therapist concerns that iCBT is impersonal by increasing contact and opportunities for tailoring treatment. No hypotheses were made about therapist time; HWRQ and 2W support could feasibly increase, decrease or result in no changes in amount of time therapists required to deliver support. We did not expect differences between therapists employed by the iCBT clinic or community mental health clinic as past research has not found meaningful differences between these two groups (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016) and all therapists, regardless of setting, specialized in the delivery of iCBT; nevertheless, since there is therapist turnover, therapist setting was controlled for through random assignment. The two-way interaction between HWRQ/NHWRQ and 1W/2W was considered exploratory.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and ethics

This study was a pragmatic 2 × 2 × 2 factorial randomized controlled trial. A factorial trial was chosen as it allows for examination of varying conditions as well as interactions without significantly increasing sample sizes (Kahan et al., 2020) and is recommended when research is focused on optimizing treatment (Collins et al., 2005). The three random factors included were: HWRQ versus NHWRQ, 1W versus 2W support, and iCBT clinic versus community clinic. The nature of the study did not allow for blinding of therapists or patients to treatment group. The trial received research ethics board approval from the University of Regina and was registered (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03957330). The trial design included assessment of heath care usage and work status and a one-year follow-up; this data will be examined and reported on at a later time pending assessment of how data collection was impacted by COVID-19 public health measures (one-year follow-up data collection began May 2020 and will conclude November 2020). A total sample size of 505 participants was calculated as sufficient to detect small between group effects (d = 0.25) and two-way interactions, with power at 80% and alpha of 0.05. Conservatively, we increased the sample to 631 to allow for 25% drop-out.

2.2. Patient recruitment, screening, and randomization

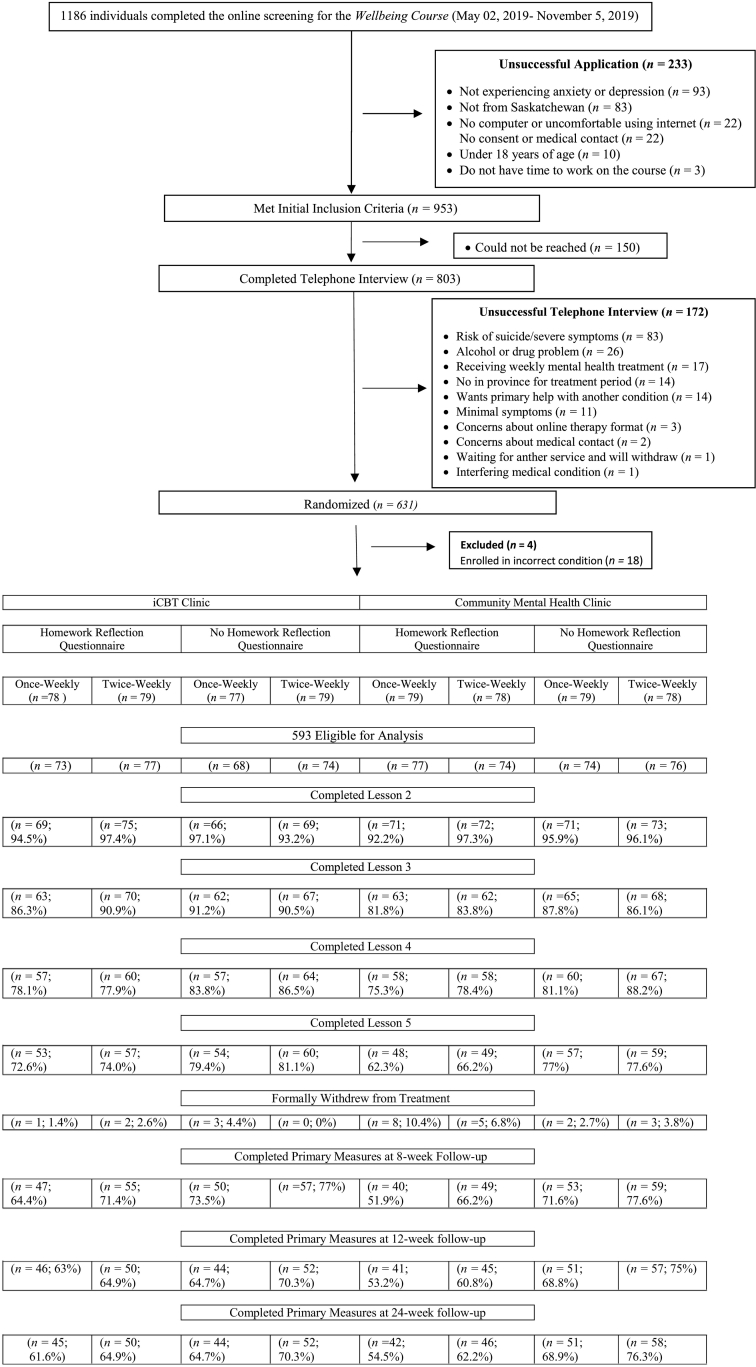

Recruitment took place between May 2 and November 5, 2019. Interested patients began by visiting the Online Therapy Unit website (www.onlinetherapyuser.ca) completing an online consent form, followed by an online screening questionnaire and then telephone interview. To be eligible, patients had to: 1) be over the age of 18; 2) self-report at least mild (≥5) symptoms of anxiety and/or depression on the primary outcome measures listed below; 3) be a resident of Saskatchewan; 4) have access to a computer and the Internet; 5) be within Saskatchewan for the 8-week treatment; 6) provide a medical contact for emergency purposes; and 7) have interest in and consent to iCBT. Exclusion criteria included: 1) severe symptoms and high risk of suicide; 2) severe alcohol or drug problems; 3) weekly mental health treatment; 4) seeking help for a different mental health condition; and 5) self-reported medical condition that would interfere with treatment. Of note, iCBT was not limited to those who have scores on measures in the clinical range as past evidence suggests that patients in the nonclinical range show significant benefit from iCBT (e.g., Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2020). Also of note, we did not conduct diagnostic interviews but instead used primary and secondary measures below to examine patient symptom severity. Immediately after being accepted to the trial, screeners used Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) to randomly assign patients meeting the above conditions into 1 of 8 unique conditions based on three levels: Level 1 (HWRQ vs. NHWRQ); Level 2 (1W vs. 2W) and Level 3 (iCBT clinic vs. community clinic). The computer-generated, permuted block randomization, with a fixed block size of 8, created a 1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1 allocation ratio. See Fig. 1 for patient flow.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow from screening to 24-week follow-up.

2.3. Intervention

All eligible patients received access to the 8-week 5 lesson transdiagnostic iCBT program called the Wellbeing Course (in depth description can be found in Titov et al., 2015), developed by the eCentreClinic at Macquarie University and licensed by the Online Therapy Unit. The Wellbeing Course consists of 5 core lessons: 1) an introduction to the cognitive behavioural model of anxiety and depression; 2) information about cognitive symptoms and thought challenging; 3) information about physical symptoms, de-arousal strategies (controlled breathing), and pleasant activity scheduling; 4) information about behavioural symptoms and graded exposure; and 5) relapse prevention and goal setting. Each lesson consists of the following components: 1) 50 to 60 presentation-like slides; 2) a downloadable guide that includes recommended HW; 3) case stories based on previous patients' experiences; and 4) a document containing frequently asked questions. Additional resources (i.e., assertiveness, communication skills, managing beliefs, managing worry, mental skills, panic, posttraumatic stress disorder, sleep, emergency information) are accessible to patients at any time. The five lessons are released to patients gradually over 8 weeks based on elapsed time (lesson 1 opens immediately; lesson 2 becomes available at start of week 2, lesson 3 at start of week 4, lesson 4 at start of week 5, lesson 5 at start of week 7) but also completion of the previous lesson. Brief automated emails notify patients about the availability and content of lessons (i.e., as soon as they are enrolled, patients receive one automated email each week that outlines the topic of the lesson).

2.4. Treatment conditions

2.4.1. Level one: HWRQ

At the beginning of lessons 2–5 and then at post-treatment, patients in the HWRQ condition answer questions about their response to the previous lesson and assigned HW. Specifically, patients were asked about how much of the lesson they were able to review (‘None’, ‘A little’, ‘Some’, ‘A lot’, or ‘All’), effort they put into the skills for the week (‘None’, ‘A little’, ‘Some’, ‘A lot’, or ‘A great deal’), how difficult it was to practice the skills (‘Not at all’, ‘Somewhat’, ‘Moderately’, ‘Very’, ‘Extremely’, or ‘Cannot rate at this point’), how understandable the lesson was (‘Not at all’, ‘Somewhat’ ‘Moderately’, ‘Very’, ‘Extremely’, or ‘Cannot rate at this point’), and how helpful the skill was (‘Not at all’, ‘Somewhat’ ‘Moderately’, ‘Very’, ‘Extremely’, or ‘Cannot rate at this point’). Patients were asked optional open-ended questions about any difficulties they had with practicing the skill/skills from the previous lesson and to provide an example of how they had used the skill/skills in the previous week. Patients were also asked about the extent to which they have used strategies from previous lessons (‘Not at all’, ‘A little’, ‘A lot’, or ‘A great deal’) and to share an example of the skills they were working on from previous lessons. Finally, patients were asked to indicate whether they had reviewed any of the additional resources and to provide an example of any skills they were practicing from the additional resources. Therapists were instructed to review the patients' HWRQ responses and to tailor their emails based on patient responses. Patients in the NHWRQ condition did not answer these questionnaires. In both HWRQ and NHWRQ, patients were informed they could email their therapist at any time to discuss HW or other issues they wanted to raise with the therapist.

2.4.2. Level two: support frequency

In both 1W and 2W conditions, therapists were instructed to send a secure email to their patients on a pre-determined day each week. Emails were to be formulated based on review of patient progress on the completion of lessons, symptom questionnaires, the HWRQ if applicable and emails from patients. The emails were expected to take approximately 15 min although therapists had the flexibility to increase amount of time spent when clinically indicated (i.e., increase in symptoms, suicidal ideation). In the 2W condition, therapists were additionally instructed to email their patients on a second pre-determined day each week, typically spaced out by two days (e.g., Monday/Thursday). The purpose of the second weekly email was to follow-up on any new emails from the patient or newly completed questionnaires; therapists were instructed to spend 10 min or less on this second email, although increased time could be taken if clinically indicated. If there was no new information from patients, the therapist left a brief email to indicate that the therapist had checked in on the patient and would email again on the next designated check-in date. In both 1W and 2W emails, therapists were to: (1) show warmth and concern; (2) provide feedback on any new completed questionnaires; (3) highlight relevant lesson content; (4) address patient questions about skill acquisition or challenges; (6) reinforce progress and practicing skills; (7) manage any risks (e.g., suicide); and (8) remind patients of course procedures as needed (e.g., timelines, next check-in). In both 1W and 2W conditions, therapists were instructed to call the patient by telephone when clinically indicated (e.g., increase in symptom scores of five points or more, endorsed suicidal ideation, patient had not logged on in a week, patient requested phone contact).

2.4.3. Level three: therapist setting

Patients were either assigned to therapists employed by the iCBT clinic or the community mental health clinic. The iCBT clinic is based at the University of Regina and focused on iCBT delivery, but also iCBT research. The community mental health clinic primarily focuses on face-to-face services and iCBT represents a small subservice within the clinic. Although the locations differ in terms of overall focus, in both locations, iCBT represented the primary workload of therapists involved in this study. All therapists received training (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2012) and had regular supervision in iCBT (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2018b).

2.5. Outcomes

Unless otherwise indicated, all primary and secondary measures were administered pre-treatment, and at 8, 12, and 24-weeks after randomization.1 Primary outcome measures were also administered at the beginning of Lessons 2–5 to assist therapists in monitoring symptoms.

2.5.1. Primary outcomes

2.5.1.1. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a validated 9-item self-report measure of depression with total scores ranging from 0 to 27 (Kroenke et al., 2001, Kroenke et al., 2010). A score of <5 has been used to indicate minimal depression and ≥10 on the PHQ-9 has been used as a cut-off score for probable major depressive disorder (Manea et al., 2012). Cronbach's alpha in this study ranged from 0.84 to 0.87.

2.5.1.2. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a validated 7-item self-report measure of anxiety with total scores ranging from 0 to 21 (Spitzer et al., 2006). A score of <5 has been used to indicate minimal anxiety and ≥10 on the GAD-7 has been used to identify those likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (Spitzer et al., 2006). Cronbach's alpha in this study ranged from 0.87 to 0.91.

2.5.2. Secondary outcomes

2.5.2.1. Kessler Distress Scale (K-10)

The K-10 is a validated questionnaire of psychological distress with scores ranging from 0 to 50 (Kessler et al., 2002). Cronbach's alpha in this study ranged from 0.88 to 0.93.

2.5.2.2. Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)

The SDS includes three items assessing functional impairment in work/school, social life, and family life, with each item rated 0 to 10 creating a total score ranging from 0 to 30 (Sheehan, 1983). The scale has strong psychometric properties (Titov et al., 2015). The Cronbach's alpha in this study ranged from 0.83 to 0.89.

2.5.2.3. Panic Disorder Severity Scale Self-Report (PDSS-SR)

The PDSS-SR is a validated 7-item questionnaire assessing panic disorder symptoms with total scores ranging from 0 to 28 (Shear et al., 2001) and a score ≥8 used to identify those who are likely to have panic disorder (Allen et al., 2016). Cronbach's alpha in this study ranged from 0.88 to 0.91.

2.5.2.4. Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Scale (SIAS-6/SPS-6)

The SIAS-6 and SPS-6 each consist of 6 items that are often summed to create a reliable and valid total score of social anxiety ranging from 0 to 48 (Peters et al., 2012). A cut-off score of ≥7 on the SIAS-6 and ≥2 on the SPS-6 is suggestive of social anxiety disorder (Peters et al., 2012). Cronbach's α in this study ranged from 0.83 to 0.86 on the SIAS-6 and 0.90 to 0.93 on the SPS-6.

2.5.2.5. Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5)

At pre-screening, patients were administered the LEC-5 self-report questionnaire to assess exposure to various potentially traumatic experiences (Weathers et al., 2013a). Patients endorsing more than one event were asked to select the event causing the most distress.

2.5.2.6. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

Patients who endorsed a distressing traumatic event on the LEC at pre-screening were administered the PCL-5, which consists of 20 items assessing posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 80 (Weathers et al., 2013b). The scale has strong psychometric properties (Blevins et al., 2015). As recommended by Weathers et al. (2013b) a score ≥ 33 was used to identify those with a likely diagnosis of PTSD. Cronbach's α in this study ranged from 0.93 to 0.95.

2.5.3. Treatment engagement

The following indicators were used to assess various aspects of treatment engagement, including number of: lessons accessed, days logging into the website, emails sent to therapist, emails from therapist to patient, and phone calls between patient and therapist.

2.5.4. Treatment experiences

2.5.4.1. HWRQ

As described above, patients in the HWRQ condition were administered HWRQs at five time-points during the iCBT course (i.e., at the beginning of lessons 2–5 and at the beginning of 8-week post-treatment questionnaires).

2.5.4.2. Working Alliance Inventory Short-Form (WAI-SR)

The WAI-SR, administered at post-treatment, includes 12 items representing three subscales: agreement on therapy tasks, agreement on therapy goals, and development of a bond between the therapist and patient (Hatcher and Gillaspy, 2006). Subscale scores range from 5 to 20 and the total score ranges from 15 to 60. Cronbach's alpha for the total scale was 0.94 and 0.92, 0.89, and 0.91 for the bond, task, and goal subscales, respectively.

2.5.4.3. Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ)

The CEQ includes three items assessing treatment credibility summed to create a total score ranging from 3 to 27 (Devilly and Borkovec, 2000). This measure was administered during the online screening and at 8 and 12-week follow-up, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.77 to 0.86.

2.5.4.4. Treatment satisfaction

At post-treatment, patients rated their satisfaction with various aspects of treatment (i.e., overall treatment, quality of materials, phone calls and emails from therapists) on “1-very dissatisfied” to “5-very satisfied” scales. Additional questions asked included whether the treatment was worth their time (“Yes” or “No”) and whether they would recommend the treatment to a friend (“Yes” or “No”). Patients also rated the extent to which the course affected their confidence in managing symptoms and their motivation to seek out future treatment if needed (rated “1-greatly reduced” to “5-greatly increased”).

2.5.4.5. Negative effects

Negative effects or events associated with iCBT were assessed at post-treatment. Patients were first asked whether they had experienced a negative effect or event (“Yes” or “No”), which was followed by questions about the impact the negative effect had on their life, as well as how much of an effect the event continued to have on their life (rated “0 - no negative impact” to “3 - severe negative impact”).

2.6. Therapist focus groups and supervisor interviews

Focus groups with therapists (approximately 90 min) and interviews (approximately 30 min) with supervisors were held after one-third of patients were enrolled in the trial and at the end of the trial. At each time point, separate focus groups were held with therapists at each site. All therapists had experience with all treatment conditions. At the same time periods, in-person interviews were held with supervisors in each location. The focus groups/interviews were led by an experienced female researcher with a graduate degree in applied psychology who was employed by the iCBT clinic to conduct qualitative research. In advance of the sessions, therapists/supervisors were informed that they would be asked about positive and negative perceptions of HWRQ and 2W support. The end of trial focus groups also included a review of themes identified during the first round and discussion of any changes in perceptions over the course of the trial. An audio recorder and scribe/note taker were used to ensure data accuracy.

2.7. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the patient sample and chi-square tests and generalized linear models assessed for any pre-treatment group differences. Following intention-to-treat principles (Hollis and Campbell, 1999), replacement values were generated for any missing values in dependent variables. The appropriateness of a missing at random assumption (MAR; Little and Rubin, 2014) was evaluated by comparing missing response rates across demographic and symptom variables. As in previous research (Karin et al., 2018a), the number of lessons completed was determined to be the dominant variable for predicting missing data at post-treatment (Wald's χ2 = 327, p < .001, Nagelkerke R Square = 44.0%) and at 12- (Wald's χ2 = 179, p < .001, Nagelkerke R Square = 23.6%) and 24-week follow-up (Wald's χ2 = 153, p < .001, Nagelkerke R Square = 20.0%). Based on this finding, a multiple imputation procedure was implemented for dependent variables controlling for lesson completion, group, pre-treatment symptom severity, and outcome measurements at adjacent time periods.

Next, differences in outcomes between therapist settings were evaluated and consistent with past research (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016), no significant differences were found; as such, no further quantitative analysis of therapist setting was undertaken. Analyses focused on examination of main effects or interactions involving HWRQ vs. HWNRQ and 1W vs. 2W. The analysis was carried out using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to estimate mean outcomes while accounting for within-subject correlation using robust error estimates (Hubbard et al., 2010; Liang and Zeger, 1986). Consistent with previous recommendations (Karin et al., 2018b), a gamma distribution with log-link was used to accommodate skewed response distributions. The working correlation structure for the GEE was an unstructured correlation, but for some imputed dependent variables (i.e. PHQ-9, SDS, and SIAS-6/SPS-6) the unstructured estimate did not converge. For these variables, a fixed correlation was specified based on the correlations that did converge (models for PHQ-9, SDS, and SIAS-6/SPS-6 used fixed correlations). According to statistical theory the parameter estimates and marginal means are still consistent and unbiased even if the working correlation is misspecified, although they are less efficient (Liang and Zeger, 1986).

To compare outcomes between treatment groups, marginal means were estimated examining groups (HWRQ vs. NHWRQ; 1W vs. 2W), interactions, and time (pre-treatment, 8, 12, and 24-weeks post-enrollment). Rates of change as a proportion of pre-treatment measurements and Cohen's d effect sizes were estimated from pre-treatment to post-treatment and to 24-week follow-up along with 95% confidence intervals. The GEE models were fit using R (R Core Team, 2020) and the geepack package (Højsgaard et al., 2006; Yan and Fine, 2004; Yan, 2002). The imputations were created using the mice package (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oushoorn, 2011). Analyses were also conducted to examine whether treatment engagement and treatment experiences varied as a function of group and interactions between groups. Two-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine continuous outcome variables and factorial logistic regression analyses to examine categorical outcome variables. Consistent with past research (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016; Titov et al., 2015), we examined reliable change on primary outcomes at post-treatment and 24-week follow-up. For the PHQ-9, reliable recovery was defined as patients scoring >9 at pre-treatment, <10 at post-treatment, and having a 6-point decrease or greater; reliable improvement was defined as a 6-point or greater decrease; deterioration was defined as a 6-point or greater increase; and no change was defined as not changing at least 6 points in either direction. The same approach was used for the GAD-7 except the critical value was 4. Alpha was adjusted from 0.05 to 0.01 for all analyses as a partial control for the number of analyses conducted.

Focus group and interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, de-identified and analyzed using QSR International's (2018) NVivo 12 qualitative analysis software as this software allows the researcher to classify and sort statements into themes (e.g., statements could be classified as pertaining to benefit or challenge for patients or therapists). A descriptive, inductive approach to thematic analysis was used to identify themes across the focus groups and interviews (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The facilitator read all transcripts closely to obtain an initial impression of the data and then engaged in inductive coding, wherein basic codes that represent each unit of meaning were derived. A second qualitative researcher associated with, but not employed by the iCBT clinic, reviewed the transcripts and themes were refined. A third researcher then reviewed the themes to sort the individual codes into those pertaining to the patient and those pertaining to the therapist. Participants served as the final check of themes to ensure they were an accurate reflection of the focus groups and interviews. Attention was given to whether themes changed at the two time points and whether there were notable differences between sites.

3. Results

3.1. Patient background

Patient background variables at pre-treatment are reported in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 37.23 years (SD = 15.89), 71.8% (n = 426) were women, 90.7% (n = 538) were Caucasian, 62.2% (n = 369) were married/common-law, 48.5% (n = 288) reported some university education, 69.8% (n = 414) reported part- or full-time employment, and 44.9% (n = 266) reported living in a large city (i.e., >200,000 residents). The majority of patients reported using psychotropic medication (56.8%; n = 377) and had pre-treatment symptoms of depression (64.6%; n = 383), generalized anxiety (62.7%; n = 372), and social anxiety (51.8%; n = 307) in the clinical range. Additionally, at pre-treatment, 40.0% (n = 237) had scores suggestive of panic disorder and 26.6% (n = 158) had scores suggestive of posttraumatic stress disorder. On average, patients scored above clinical cut-offs on 2.63 (SD = 1.51) of these five symptom measures. Only 11.5% of patients had no score in the clinical range. No significant pre-treatment group differences on the variables were found (p range: .15 to .91).

Table 1.

Pre-treatment patient characteristics by group.

| Variable | All groups (n = 593) |

Once-weekly support |

Twice-weekly support |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iCBT clinic (n = 141) |

Community clinic (n = 151) |

iCBT clinic (n = 151) |

Community clinic (n = 150) |

|||||||||||||||

| HWRQ |

NHWRQ |

HWRQ |

NHWRQ |

HWRQ |

NHWRQ |

HWRQ |

NHWRQ |

|||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.23 (15.89) | 38.25 (13.3) | 35.87 (11.45) | 36.82 (13.86) | 38.73 (13.09) | 34.56 (10.74) | 38.14 (14.04) | 34.69 (13.06) | 37.68 (14.17) | |||||||||

| Range | 18–88 | 18–88 | 18–69 | 18–89 | 18–66 | 18–63 | 18–72 | 18–62 | 19–69 | |||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 156 | 26.3 | 24 | 65.8 | 19 | 27.9 | 15 | 19.5 | 23 | 31.1 | 18 | 23.4 | 21 | 28.4 | 14 | 18.9 | 22 | 28.9 |

| Female | 426 | 71.8 | 48 | 32.9 | 49 | 72.1 | 61 | 79.2 | 48 | 64.9 | 56 | 72.7 | 52 | 70.3 | 59 | 79.7 | 53 | 69.7 |

| Two spirit | 4 | 0.7 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.3 | – | – | 1 | 1.4 | – | – |

| Non-binary | 4 | 0.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2.7 | 1 | 1.3 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1.3 |

| Not listed | 1 | 0.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Prefers not to disclose | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 1.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1.4 | – | – | – | – |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Single/never married | 167 | 28.2 | 20 | 27.4 | 23 | 33.8 | 20 | 26.0 | 16 | 21.6 | 19 | 24.7 | 24 | 32.4 | 18 | 24.3 | 27 | 35.5 |

| Married/common-law | 369 | 62.2 | 45 | 61.6 | 38 | 55.9 | 51 | 66.3 | 50 | 67.6 | 51 | 66.3 | 43 | 58.1 | 51 | 68.9 | 40 | 52.6 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 57 | 9.7 | 16 | 11 | 7 | 10.4 | 6 | 7.8 | 8 | 10.8 | 7 | 9.1 | 7 | 9.6 | 5 | 6.8 | 9 | 11.8 |

| Education | ||||||||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 8 | 1.3 | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2.7 | 3 | 3.9 |

| High school diploma | 118 | 19.9 | 17 | 23.3 | 12 | 17.6 | 21 | 27.3 | 17 | 23.0 | 12 | 15.6 | 14 | 18.9 | 15 | 20.3 | 10 | 13.2 |

| Post high school certificate/diploma | 179 | 30.2 | 18 | 24.7 | 25 | 36.8 | 19 | 24.7 | 26 | 35.1 | 26 | 33.8 | 23 | 31.1 | 19 | 25.7 | 23 | 30.3 |

| University education | 288 | 48.5 | 37 | 50.6 | 29 | 42.6 | 37 | 34.1 | 31 | 42 | 39 | 50.7 | 37 | 50 | 38 | 51.4 | 40 | 52.6 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Employed part-time/full-time | 414 | 69.8 | 53 | 72.6 | 49 | 72.1 | 50 | 64.9 | 55 | 74.3 | 54 | 70.1 | 47 | 63.5 | 54 | 73.0 | 52 | 68.4 |

| Unemployed | 38 | 6.4 | 5 | 6.8 | 7 | 10.3 | 5 | 6.5 | 4 | 5.4 | 3 | 3.9 | 4 | 5.4 | 5 | 6.8 | 5 | 6.6 |

| Homemaker | 47 | 7.9 | 6 | 6.8 | 2 | 2.9 | 10 | 13.0 | 8 | 10.8 | 7 | 9.1 | 4 | 5.4 | 4 | 5.4 | 6 | 7.9 |

| Student | 37 | 6.2 | 4 | 5.5 | 3 | 4.4 | 3 | 3.9 | 3 | 4.1 | 8 | 10.4 | 8 | 10.8 | 4 | 5.4 | 4 | 5.3 |

| Disability | 29 | 4.9 | 2 | 2.7 | 5 | 7.4 | 4 | 5.2 | 2 | 2.7 | 4 | 5.2 | 4 | 5.4 | 4 | 5.4 | 4 | 5.3 |

| Retired | 28 | 4.7 | 3 | 4.1 | 2 | 2.9 | 5 | 6.5 | 2 | 2.7 | 1 | 1.3 | 7 | 9.5 | 3 | 4.1 | 5 | 6.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 538 | 90.7 | 70 | 95.9 | 64 | 94.1 | 70 | 90.9 | 67 | 89.6 | 69 | 89.6 | 62 | 83.8 | 67 | 90.5 | 69 | 90.8 |

| Indigenous | 31 | 5.2 | 2 | 2.7 | 2 | 2.9 | 4 | 5.2 | 3 | 4.1 | 5 | 6.5 | 10 | 13.5 | 3 | 4.1 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Other | 24 | 4.1 | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.9 | 3 | 3.9 | 4 | 5.5 | 3 | 3.9 | 2 | 2.8 | 4 | 5.4 | 5 | 6.6 |

| Location | ||||||||||||||||||

| Large city (over 200,000) | 266 | 44.9 | 35 | 47.9 | 27 | 39.7 | 31 | 40.3 | 33 | 44.6 | 39 | 50.6 | 39 | 52.7 | 33 | 44.6 | 29 | 38.2 |

| Small to medium city | 155 | 26.1 | 17 | 23.3 | 22 | 32.4 | 19 | 24.7 | 23 | 31.1 | 16 | 20.8 | 18 | 24.3 | 12 | 16.2 | 28 | 36.8 |

| Small rural location (under 10,000) | 172 | 29 | 21 | 28.8 | 19 | 27.9 | 27 | 35.1 | 18 | 24.3 | 22 | 28.6 | 17 | 23 | 29 | 39.2 | 19 | 25 |

| Mental health characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||

| Taking psychotropic medications | 337 | 56.8 | 46 | 63.0 | 38 | 55.9 | 44 | 57.1 | 41 | 55.4 | 41 | 53.2 | 50 | 67.6 | 39 | 52.7 | 38 | 50.0 |

| Pre-treatment GAD-7 ≥ 10 | 372 | 62.7 | 46 | 63 | 48 | 70.6 | 51 | 66.2 | 43 | 58.1 | 48 | 62.3 | 40 | 54.1 | 44 | 59.5 | 52 | 68.4 |

| Pre-treatment PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | 383 | 64.6 | 51 | 69.9 | 40 | 58.8 | 52 | 67.5 | 40 | 54.1 | 48 | 62.3 | 52 | 70.3 | 52 | 70.3 | 48 | 63.2 |

| Pre-treatment PDSS-SR ≥8 | 237 | 40.0 | 25 | 34.2 | 28 | 41.2 | 34 | 44.2 | 31 | 41.9 | 24 | 31.2 | 30 | 40.5 | 33 | 44.6 | 32 | 42.1 |

| Pre-treatment SIAS-6 ≥ 7 and SPS-6 ≥ 2 | 307 | 51.8 | 33 | 45.2 | 44 | 64.7 | 42 | 54.5 | 25 | 33.8 | 46 | 59.7 | 37 | 50 | 42 | 56.8 | 38 | 50 |

| LEC-5 trauma and PCL-5 > 32 | 158 | 26.6 | 19 | 26 | 13 | 19.1 | 20 | 26 | 17 | 23 | 25 | 32.5 | 19 | 25.7 | 23 | 31.1 | 22 | 28.9 |

| No clinical scores | 68 | 11.5 | 8 | 11 | 3 | 4.4 | 8 | 10.4 | 10 | 13.5 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 12.2 | 9 | 12.2 | 11 | 14.5 |

| Mean number of measures above cut-off (SD) | 2.63 (1.51) | 2.38 (1.56) | 2.54 (1.35) | 2.58 (1.62) | 2.11 (1.40) | 2.48 (1.54) | 2.41 (1.40) | 2.62 (1.57) | 2.53 (1.68) | |||||||||

| Pre-treatment credibility | 26.96 (6.08) | 27.40 (6.19) | 27.90 (5.69) | 26.69 (5.79) | 27.66 (5.42) | 26.53 (5.79) | 25.44 (6.91) | 28.34 (5.02) | 25.88 (7.19) | |||||||||

Note. NHWRQ = no homework reflection questionnaires; HWRQ = homework reflection questionnaires; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PDSS-SR = Panic Disorder Severity Scale-Self Report; SIAS-6/SPS-6 = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale-6 and Social Phobia Scale-6; LEC-5 = Life Events Checklist for DSM-5; PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5.

3.2. Primary outcomes

The means, standard deviations, percentage reductions, and Cohen's d effect sizes for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 for groups are presented in Table 2. The GEE analyses revealed statistically significant time effects for the PHQ-9 (p < .001) and GAD-7 (p < .001) showing that these scores reduced over time for all treatment groups. There were no statistically significant main effects or interactions (p range .07–.92).

Table 2.

Estimated marginal means, 95% confidence intervals, percentage changes, and effect sizes (Cohen's d) for the primary and secondary outcomes by group pooled imputations.

| Estimated marginal means |

Percentage changes from pre-treatment |

Within-group effect sizes from pre-treatment |

Post-treatment between group effect sizeb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | 12-week follow-up | 24-week follow up | To post-treatment | To 24-week follow-up | To post-treatment | To 24-week follow-up | ||

| Primary outcomes | |||||||||

| PHQ-9a | |||||||||

| 1W | 11.96 (5.57) | 7.13 (5.67) | 6.32 (5.21) | 5.70 (4.97) | 40 [32, 48] | 52 [44, 59] | 0.70 [0.57, 0.83] | 1.00 [0.86, 1.14] | |

| 2W | 11.81 (5.49) | 6.67 (5.54) | 6.09 (4.82) | 6.44 (5.21) | 44 [35, 51] | 45 [39, 51] | 0.77 [0.64, 0.90] | 0.82 [0.69, 0.95] | 0.09 [−0.07, 0.25] |

| NHWRQ | 11.70 (5.57) | 7.03 (6.05) | 5.98 (4.83) | 5.72 (4.94) | 40 [30, 49] | 51 [45, 57] | 0.69 [0.56, 0.82] | 0.97 [0.83, 1.11] | |

| HWRQ | 12.08 (5.49) | 6.77 (5.13) | 6.45 (5.19) | 6.42 (5.24) | 44 [37, 50] | 47 [39, 54] | 0.78 [0.65, 0.91] | 0.85 [0.72, 0.98] | 0.05 [−0.11, 0.21] |

| GAD-7 | |||||||||

| 1W | 11.71 (5.06) | 6.32 (4.98) | 5.41 (4.51) | 5.05 (4.56) | 46 [37, 53] | 57 [49, 63] | 0.82 [0.69, 0.95] | 1.13 [0.98, 1.28] | |

| 2W | 11.48 (4.91) | 5.80 (4.89) | 5.09 (4.13) | 5.94 (4.94) | 49 [41, 57] | 48 [42, 54] | 0.91 [0.78, 1.04] | 0.88 [0.75, 1.01] | 0.12 [−0.05, 0.28] |

| NHWRQ | 11.58 (4.98) | 6.02 (5.05) | 5.00 (4.08) | 5.30 (4.73) | 48 [38, 56] | 54 [48, 60] | 0.88 [0.74, 1.01] | 1.05 [0.91, 1.19] | |

| HWRQ | 11.61 (5.00) | 6.10 (4.82) | 5.51 (4.54) | 5.65 (4.82) | 47 [40, 54] | 51 [44, 58] | 0.86 [0.73, 0.99] | 0.96 [0.82, 1.10] | −0.02 [−0.18, 0.14] |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||||

| K10 | |||||||||

| 1W | 27.41 (7.43) | 21.10 (7.61) | 19.99 (7.59) | 19.14 (7.69) | 23 [17, 28] | 30 [26, 35] | 0.73 [0.60, 0.86] | 1.01 [0.87, 1.15] | |

| 2W | 27.75 (7.56) | 21.06 (7.81) | 19.93 (7.76) | 20.82 (8.30) | 24 [19, 29] | 25 [21, 29] | 0.77 [0.64, 0.90] | 0.81 [0.68, 0.94] | 0.01 [−0.16, 0.17] |

| NHWRQ | 27.20 (7.37) | 21.38 (8.15) | 19.68 (7.53) | 19.30 (7.81) | 21 [15, 27] | 29 [25, 33] | 0.68 [0.55, 0.81] | 0.96 [0.82, 1.10] | |

| HWRQ | 27.96 (7.60) | 20.79 (7.24) | 20.24 (7.80) | 20.65 (8.22) | 26 [21,30] | 26 [21,31] | 0.83 [0.70, 0.96] | 0.85 [0.72, 0.98] | 0.08 [−0.08, 0.24] |

| PDSS-SR | |||||||||

| 1W | 6.74 (5.75) | 4.69 (5.15) | 3.62 (4.33) | 3.00 (4.21) | 30 [14, 44] | 55 [45, 64] | 0.32 [0.20, 0.44] | 0.71 [0.58, 0.84] | |

| 2W | 6.67 (5.89) | 4.20 (4.87) | 3.54 (4.47) | 3.39 (4.04) | 37 [21, 50] | 49 [40, 57] | 0.41 [0.29, 0.53] | 0.60 [0.48, 0.72] | 0.10 [−0.06, 0.26] |

| NHWRQ | 6.86 (5.72) | 4.52 (5.05) | 3.63 (4.38) | 2.74 (3.72) | 34 [16, 48] | 60 [51, 67] | 0.37 [0.25, 0.49] | 0.81 [0.68, 0.94] | |

| HWRQ | 6.55 (5.91) | 4.35 (4.97) | 3.53 (4.42) | 3.72 (4.44) | 34 [18, 46] | 43 [32, 53] | 0.36 [0.24, 0.48] | 0.50 [0.38, 0.62] | 0.03 [−0.13, 0.19] |

| SIAS-6/SPS-6a | |||||||||

| 1W | 14.05 (10.23) | 10.81 (8.62) | 9.94 (9.43) | 9.12 (8.97) | 23 [13,32] | 35 [26, 43] | 0.31 [0.19, 0.43] | 0.51 [0.39, 0.63] | |

| 2W | 15.17 (10.71) | 11.98 (9.50) | 10.39 (9.92) | 10.38 (9.58) | 21 [11,30] | 32 [23, 39] | 0.28 [0.16, 0.39] | 0.45 [0.33, 0.57] | −0.12 [−0.28, 0.04] |

| NHWRQ | 14.00 (10.13) | 10.54 (8.73) | 9.42 (9.18) | 8.72 (8.54) | 25 [14, 34] | 38 [30, 45] | 0.33 [0.21, 0.45] | 0.56 [0.44, 0.68] | |

| HWRQ | 15.22 (10.80) | 12.29 (9.35) | 10.96 (10.09) | 10.86 (9.88) | 19 [10, 28] | 29 [19, 37] | 0.25 [0.14, 0.36] | 0.40 [0.28, 0.52] | −0.18 [−0.34, −0.02] |

| PCL-5 | |||||||||

| 1W | 32.02 (18.24) | 15.68 (12.58) | 22.43 (16.69) | 19.77 (16.10) | 51 [40, 60] | 38 [24, 50] | 0.98 [0.84, 1.12] | 0.66 [0.53, 0.79] | |

| 2W | 34.05 (16.98) | 17.22 (14.31) | 19.72 (16.40) | 22.94 (16.46) | 49 [39, 58] | 33 [22, 42] | 0.93 [0.79, 1.06] | 0.54 [0.42, 0.66] | −0.13 [−0.35, 0.09] |

| NHWRQ | 30.85 (17.50) | 16.12 (13.68) | 20.67 (16.74) | 20.88 (16.76) | 48 [39, 56] | 32 [20, 42] | 0.89 [0.75, 1.03] | 0.53 [0.41, 0.65] | |

| HWRQ | 35.35 (17.44) | 16.75 (13.46) | 21.40 (16.47) | 21.72 (15.98) | 53 [43, 61] | 39 [28, 48] | 1.02 [0.88, 1.16] | 0.67 [0.54, 0.79] | −0.05 [−0.27, 0.17] |

| SDSa | |||||||||

| 1W | 16.61 (7.81) | 10.54 (8.64) | 8.73 (8.11) | 7.01 (7.58) | 37 [26, 46] | 58 [50, 64] | 0.55 [0.43, 0.67] | 1.03 [0.89, 1.17] | |

| 2W | 16.74 (7.72) | 9.30 (8.07) | 9.18 (8.40) | 8.65 (8.29) | 44 [34, 53] | 48 [40, 55] | 0.70 [0.57, 0.83] | 0.79 [0.66, 0.92] | 0.15 [−0.01, 0.31] |

| NHWRQ | 16.48 (7.76) | 9.59 (8.51) | 8.82 (8.44) | 6.84 (7.60) | 42 [32, 50] | 59 [51, 65] | 0.65 [0.52, 0.78] | 1.06 [0.92, 1.20] | |

| HWRQ | 16.88 (7.77) | 10.23 (8.26) | 9.08 (8.08) | 8.87 (8.23) | 39 [30, 48] | 47 [40, 54] | 0.60 [0.48, 0.72] | 0.77 [0.64, 0.90] | −0.08 [−0.24, 0.08] |

Note. 1W = once-weekly; 2W = twice-weekly; NHWRQ = no homework reflection questionnaires; HWRQ = homework reflection questionnaires; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; K10 = Kessler-10; PDSS-SR = Panic Disorder Severity Scale-Self Report; SIAS-6/SPS-6 = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale-6 and Social Phobia Scale-6; PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; standard deviations are shown in rounded parentheses for the estimated means; 95% confidence intervals are shown in square parentheses for the percentage changes and effect sizes.

A fixed working correlation structure was used for the PHQ-9, SIAS-6/SPS-6, and SDS models.

For 2W: Cohen's d compared to 1W. For HWRQ: Cohen's d compared to NHWRQ.

3.3. Secondary outcomes

The means, standard deviations, percentage reductions, and Cohen's d effect sizes for the secondary measures for the groups are shown in Table 2. The GEE analysis revealed statistically significant time effects for all variables (p < .001). For the PDSS-SR, the interaction between HWRQ and 24-week follow-up was significant (p = .007), such that, at this time, the NHWRQ group had a larger proportional PDSS-SR reduction than the HWRQ group (60% vs. 43%). There were no other statistically significant main effects or interactions (p range .02–.98).

3.4. Clinical significance

Percentage change and within-group effect sizes from the GEE models are available in Table 2. At post-treatment, examination of Cohen's d showed there were large effects on the GAD-7 (0.82–0.91) and PCL-5 (0.89–1.02), primarily medium effects on the PHQ-9 (0.69–0.78), K10 (0.68–0.83) and SDS (0.55–0.70), and small effects on the PDSS-SR (0.32–0.41) and SIAS-6/SPS-6 (Cohen's d: 0.25–0.41). At 24-week follow-up, effects were the same or larger for most measures with examination of Cohen's d showing mostly large effects on the GAD-7 (0.88–1.13), PHQ-9 (0.82–1.00), K10 (0.81–1.01), and SDS (0.77–1.06) and medium to large effects on the PDSS-SR (0.50–0.81), and small to medium effects on the SIAS-6/SPS-6 (0.40–0.56). For the PCL-5, the effects reduced from large to medium (0.53–0.67).

Table 3 shows results related to reliable change on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 at post-treatment and 24-week follow-up. No significant group differences were found (p range .05–.72). Overall, on the GAD-7, reviewing post-treatment and 24-week follow-up, 42.0–44.8% of patients demonstrated reliable recovery, 65.7–68.1% reliable improvement, 27.9–29.8% no change and 3.9–4.5% reliable deterioration. Overall, on the PHQ-9, reviewing post-treatment and 24-week follow-up, 32.8–38.8% of patients demonstrated reliable recovery, 43.0–48.2% reliable improvement, 49.9–53.4% no change and 1.9–3.5% reliable deterioration.

Table 3.

Reliable recovery, reliable improvement, no change, and deterioration on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 at post-treatment and 24-week follow-up using imputed data.

| All groups (%) | NHWRQ (%) | HWRQ | Significance | 1W (%) | 2W (%) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-treatment | |||||||

| PHQ-9 | |||||||

| In clinical range at assessment | 64.6 | 61.6 | 67.4 | χ2(1, N=593) = 1.93; p = .16 | 62.7 | 66.4 | χ2(1, N=593) = 0.77; p = .38 |

| Reliable recovery | 32.8 | 30.0 | 35.5 | F(1, 689) = 1.56; p = .21 | 31.7 | 33.9 | F(1, 1117) = 0.38; p = .54 |

| Reliable improvement | 43.0 | 41.6 | 44.5 | F(1, 1232) = 0.55; p = .46 | 43.1 | 43.0 | F(1, 1046) = 0.29; p = .59 |

| No change | 53.4 | 53.2 | 53.7 | F(1, 3397) = 0.13; p = .72 | 52.2 | 54.6 | F(1, 709) = 0.37; p = .55 |

| Reliable deterioration | 3.5 | 5.3 | 1.9 | F(1, 125) = 2.63; p = .11 | 4.7 | 2.4 | F(1, 141) = 1.30; p = .26 |

| GAD-7 | |||||||

| In clinical range at assessment | 62.7 | 62.7 | 62.8 | χ2(1, N=593) = 0; p = 1 | 64.4 | 61.1 | χ2(1, N=593) = 0.54; p = .46 |

| Reliable recovery | 42.0 | 41.4 | 42.6 | F(1, 2190) = 0.34; p = .56 | 42.3 | 41.6 | F(1, 3218) = 0.21; p = .64 |

| Reliable improvement | 65.7 | 67.0 | 64.5 | F(1, 275) = 0.43; p = .51 | 63.9 | 67.5 | F(1, 311) = 0.73; p = .39 |

| No change | 29.8 | 28.7 | 30.8 | F(1, 1168) = 0.33; p = .57 | 30.3 | 29.2 | F(1, 1470) = 0.24; p = .62 |

| Reliable deterioration | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.7 | F(1, 169) = 0.85; p = .36 | 5.8 | 3.3 | F(1, 158) = 1.49; p = .22 |

| 24-week follow-up | |||||||

| PHQ-9 | |||||||

| In clinical range at assessment | 64.6 | 61.6 | 67.4 | χ2(1, N=593) = 1.93; p = .16 | 62.7 | 66.4 | χ2(1, N=593) = 0.77; p = .38 |

| Reliable recovery | 38.8 | 38.2 | 39.3 | F(1, 3404) = 0.22; p = .64 | 40.0 | 37.5 | F(1, 951) = 0.45; p = .50 |

| Reliable improvement | 48.2 | 47.9 | 48.5 | F(1, 1394) = 0.25; p = .62 | 51.2 | 45.3 | F(1, 382) = 1.42; p = .23 |

| No change | 49.9 | 51.1 | 48.8 | F(1, 725) = 0.32; p = .57 | 47.0 | 52.7 | F(1, 581) = 1.44; p = .23 |

| Reliable deterioration | 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.7 | F(1, 205) = 1.49; p = .22 | 1.8 | 2.0 | F(1, 681) = 0.46; p = .50 |

| GAD-7 | |||||||

| In clinical range at assessment | 62.7 | 62.7 | 62.8 | χ2(1, N=593) = 0; p = 1 | 64.4 | 61.1 | χ2(1, N=593) = 0.54; p = .46 |

| Reliable recovery | 44.8 | 44.7 | 44.9 | F(1, 6464) = 0.15; p = .69 | 49.8 | 40.0 | F(1, 373) = 3.97; p = .05 |

| Reliable improvement | 68.1 | 70.1 | 66.3 | F(1, 521) = 0.86; p = .35 | 70.4 | 65.9 | F(1, 320) = 0.96; p = .33 |

| No change | 27.9 | 26.5 | 29.3 | F(1, 899) = 0.53; p = .47 | 26.6 | 29.2 | F(1, 769) = 0.47; p = .49 |

| Reliable deterioration | 3.9 | 3.4 | 4.5 | F(1, 298) = 0.44; p = .51 | 2.9 | 4.9 | F(1, 217) = 1.00; p = .32 |

Note. 1W = once-weekly; 2W = twice-weekly; NHWRQ = no homework reflection questionnaires; HWRQ = homework reflection questionnaires; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7.

3.5. Treatment engagement

Table 4 includes the HWRQ ratings for patients assigned HWRQ. Overall, patients rated that they reviewed ‘a lot’ of content, put in ‘some’ effort to skill development, found skills ‘somewhat’ difficult, endorsed ‘very good’ understanding of lesson material and found skills ‘moderately’ helpful. Evaluation of ratings suggested patients reviewed less content and put in less effort as the lessons progressed. The lesson content on thought challenging was rated as the most difficult to practice and the most helpful out of all lessons. The content on de-arousal strategies and pleasant activity scheduling were rated as easiest to understand.

Table 4.

Homework reflection questionnaire ratings by group.

| Combined Mean (SD) |

Once-weekly support Mean (SD) |

Twice-weekly support Mean (SD) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 |

L3 |

L4 |

L5 |

Post |

L2 |

L3 |

L4 |

L5 |

Post |

L2 |

L3 |

L4 |

L5 |

Post |

|

| n | 287 | 255 | 231 | 204 | 188 | 140 | 126 | 113 | 100 | 86 | 147 | 129 | 118 | 104 | 102 |

| Content revieweda | 3.34 (1.03) | 3.13 (1.09) | 2.97 (1.20) | 2.87 (1.27) | 2.61 (1.47) | 3.29 (1.10) | 3.13 (1.13) | 2.94 (1.16) | 2.84 (1.27) | 2.71 (1.48) | 3.39 (0.96) | 3.14 (1.06) | 3.01 (1.24) | 2.90 (1.28) | 2.53 (1.47) |

| Effort put into the skillsa | 2.31 (0.84) | 2.40 (0.84) | 2.24 (0.94) | 1.76 (0.99) | 1.54 (1.05) | 2.31 (0.89) | 2.37 (0.85) | 2.14 (0.91) | 1.72 (1.02) | 1.59 (1.14) | 2.32 (0.79) | 2.44 (0.82) | 2.33 (0.96) | 1.81 (0.97) | 1.50 (0.96) |

| Difficulty practicing skillb | 1.28 (1.01) | 1.80 (0.94) | 0.92 (0.90) | 1.61 (1.09) | 0.98 (0.90) | 1.21 (0.98) | 1.73 (0.89) | 0.93 (0.86) | 1.55 (0.98) | 0.97 (0.91) | 1.35 (1.04) | 1.88 (0.99) | 0.91 (0.94) | 1.66 (1.18) | 1.00 (0.89) |

| Understand lessonb | 2.75 (0.83) | 2.76 (0.80) | 3.04 (0.73) | 2.78 (0.78) | 2.69 (0.81) | 2.72 (0.82) | 2.68 (0.84) | 2.92 (0.79) | 2.73 (0.74) | 2.62 (0.78) | 2.77 (0.85) | 2.84 (0.76) | 3.15 (0.65) | 2.82 (0.82) | 2.75 (0.83) |

| Helpfulness of skillb | 2.22 (0.98) | 2.37 (0.96) | 2.33 (0.96) | 2.01 (1.05) | 2.21 (0.97) | 2.13 (0.98) | 2.29 (0.95) | 2.36 (0.93) | 1.89 (0.99) | 2.20 (0.92) | 2.31 (0.98) | 2.44 (0.97) | 2.31 (1.00) | 2.14 (1.10) | 2.22 (1.02) |

Note. L2 = Lesson 2; L3 = Lesson 3; L4 = Lesson 4; L5 = Lesson 5; Post = Post-treatment.

Rated on a scale of 0–4 where 0 = ‘None’, 1 = ‘A little’, 2 = ‘Some’, 3 = ‘A lot’, 4 = ‘All’.

Rated on a scale of 0–4 where 0 = ‘Not at all’, 1 = ‘Somewhat’, 2 = ‘Moderately’, 3 = ‘Very’, 4 = ‘Extremely’.

Table 5 displays treatment engagement scores. Most patients completed at least 4 lessons (81.8%, n = 481), with 73.7% (n = 437) completing all 5 lessons. Questionnaire completion rates were 69.0% (n = 409), 65.1% (n = 386) and 65.4% (n = 388) for the post-treatment, 12-week, and 24-week follow-up periods respectively. Patients, on average, had 0.95 (SD = 1.17) phone calls with their therapist. No main effects or interactions were found on these measures (p range .04–.89).

Table 5.

Program engagement by group.

| Variable | All groups (N = 593) |

Once-weekly support (n = 292) |

Twice-weekly support (n = 301) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HWRQ (n = 150) |

NHWRQ (n = 142) |

HWRQ (n = 151) |

NHWRQ (n = 150) |

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Engagement | ||||||||||

| Accessed | ||||||||||

| 4 lessons | 481 | 81.1 | 115 | 76.7 | 117 | 82.4 | 118 | 78.1 | 131 | 87.3 |

| 5 lessons | 437 | 73.7 | 101 | 67.3 | 111 | 78.2 | 106 | 70.2 | 119 | 79.3 |

| Post-treatment primary measures | 409 | 69.0 | 87 | 58.0 | 101 | 71.1 | 104 | 68.9 | 117 | 78.0 |

| 12-week primary measures | 386 | 65.1 | 87 | 58.0 | 95 | 66.9 | 95 | 62.9 | 109 | 72.7 |

| 24-week primary measures | 388 | 65.4 | 87 | 58.0 | 95 | 66.9 | 96 | 63.6 | 110 | 73.3 |

| Mean days between first and last log-in (SD) | 77.43 (46.23) | 67.12 (40.14) | 87.69 (51.10) | 67.74 (37.23) | 87.77 (51.01) | |||||

| Mean number of log-ins (SD) | 21.85 (13.15) | 20.01 (14.33) | 21.72 (12.96) | 21.01 (11.91) | 24.65 (12.94) | |||||

| Mean number of therapist emails to patient (SD) | 12.83 (4.17) | 9.08 (1.80) | 9.01 (1.57) | 16.25 (2.18) | 16.74 (1.87) | |||||

| Mean number of emails from patient to therapist (SD) | 4.70 (3.97) | 3.15 (3.01) | 3.77 (2.80) | 5.52 (4.11) | 6.29 (4.78) | |||||

| Mean number of phone calls (SD) | 0.95 (1.17) | 1.01 (1.17) | 0.88 (1.21) | 1.03 (1.09) | 0.87 (1.21) | |||||

Note. NHWRQ = no homework reflection questionnaires; HWRQ = homework reflection questionnaires.

In terms of differences in engagement, patients who received HWRQs compared to those who did not logged in fewer times (20.51 vs. 23.23 logins; F(1, 589) = 6.22, p = .01) and spent fewer days in the course from the first to their last login (67.43 vs. 87.73 days in course; F(1, 589) = 29.87, p < .001). As expected, patients who received 2W versus 1W support received more emails from their therapist (M = 16.49 vs. 9.05 therapist emails; F(1, 589) = 2350.84, p < .001). Similarly, patients who received 2W versus 1W support sent more emails to therapists (M = 5.90 vs. 3.45 patient emails; F(1, 589) = 62.22, p < .001).

3.6. Treatment experiences

Table 6 displays scores related to patient treatment experiences. Scores on the WAI-SR subscales were favourable (subscale scores ranged from 14.86–17.29 out of 20) and the treatment was perceived to be credible (M = 23 out of 27). The majority of patients indicated they were either ‘Satisfied’ or ‘Very satisfied’ with various treatment components (e.g., overall course, materials, telephone calls, emails). Nearly all patients indicated that they felt the treatment was worth their time (97.4%, n = 372), that they would recommend the treatment to a friend (97.4%, n = 372) and that the course increased or greatly increased their confidence in their ability to manage their symptoms (94.5%, n = 361). The majority also indicated that the course increased or greatly increased their motivation to seek additional help if they needed it in the future (84.3%, n = 322). No significant main effects (p range: .04–.88) or interactions (p range: .17–.84) were detected on these measures, with one exception. A significant interaction was found for how the course affected patient confidence to learn to manage symptoms (F (1,378) = 6.78, p = .01), with patients in the 1W/NHWRQ condition being most likely to indicate that their confidence had ‘Greatly increased’ (40.9%, n = 38), followed by 2W/HWRQ (33.7%, n = 32), 1W/HWRQ (31.0%, n = 26), and 2W/NHWRQ (21.8%, n = 24).

Table 6.

Treatment perceptions/experiences by patients completing post-treatment measures by group.

| Variable | All groups (N = 593) |

Once-weekly support (n = 177) |

Twice-weekly support (n = 205) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HWRQ (n = 84) |

NHWRQ (n = 93) |

HWRQ (n = 95) |

NHWRQ (n = 110) |

|||||||

| n or M (SD) | % | n or M (SD) | % | n or M (SD) | % | n or M (SD) | % | n or M (SD) | % | |

| Working alliance | ||||||||||

| WAI-SR total score | 47.55 (10.10) | 45.48 (10.36) | 47.82 (10.28) | 49.04 (10.35) | 47.54 (9.37) | |||||

| WAI-SR bond score | 17.29 (3.56) | 16.82 (3.63) | 17.33 (3.71) | 17.97 (3.34) | 16.99 (3.49) | |||||

| WAI-SR task score | 15.41 (3.43) | 14.54 (3.48) | 15.59(3.36) | 15.60 (3.80) | 15.72 (3.04) | |||||

| WAI-SR goal score | 14.86 (4.39) | 14.11 (4.66) | 14.90 (4.46) | 15.47 (4.31) | 14.83 (4.15) | |||||

| Treatment ratings | ||||||||||

| Posttreatment credibility | 23.18 (4.15) | 22.26 (4.67) | 23.57 (3.85) | 23.27 (4.44) | 23.44 (3.69) | |||||

| Satisfied/very satisfied overall | 342 | 89.6 | 71 | 84.5 | 86 | 92.4 | 83 | 87.4 | 102 | 92.7 |

| Satisfied/very satisfied with materials | 349 | 91.3 | 75 | 89.3 | 87 | 93.5 | 83 | 87.4 | 104 | 94.6 |

| Satisfied/very satisfied with telephone calls* | 179 | 74.6 | 45 | 75.0 | 46 | 73.0 | 41 | 74.5 | 47 | 75.8 |

| Satisfied/very satisfied with emails | 334 | 87.5 | 72 | 85.7 | 82 | 88.2 | 83 | 87.4 | 97 | 88.2 |

| Increased/greatly increased confidence | 361 | 94.5 | 77 | 91.7 | 90 | 96.8 | 90 | 94.8 | 104 | 94.5 |

| Increased/greatly increased motivation for other treatment | 322 | 84.3 | 76 | 90.5 | 76 | 81.7 | 82 | 86.3 | 88 | 80.0 |

| Course was worth the time (%) | 372 | 97.4 | 83 | 98.8 | 90 | 96.8 | 91 | 95.8 | 108 | 98.2 |

| Would recommend course to a friend (%) | 372 | 97.4 | 83 | 98.8 | 89 | 95.7 | 92 | 96.8 | 108 | 98.2 |

| Negative effects | ||||||||||

| Reported negative effects from treatment (%) | 46 | 12.0 | 10 | 11.9 | 11 | 11.8 | 13 | 13.7 | 12 | 10.9 |

| Negative effect impact (0–3) | 0.78 (1.12) | 0.83 (1.13) | 0.77 (1.15) | 0.75 (1.06) | 0.78 (1.14) | |||||

| Negative effect continues negative impact (0–3) | 0.43 (0.75) | 0.55 (0.87) | 0.39 (0.72) | 0.42 (0.68) | 0.40 (0.72) | |||||

| Contact preferences | ||||||||||

| Prefer no email | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Prefer automated emails | 18 | 4.7 | 5 | 6.0 | 3 | 3.2 | 4 | 4.2 | 6 | 5.5 |

| Prefer once-weekly email | 195 | 51.0 | 55 | 65.5 | 64 | 68.8 | 36 | 37.9 | 40 | 36.4 |

| Prefer twice-weekly email | 168 | 44.0 | 24 | 16.0 | 26 | 28.0 | 54 | 56.8 | 64 | 58.2 |

| Prefer no phone contact | 17 | 4.5 | 4 | 4.8 | 3 | 3.2 | 7 | 7.4 | 3 | 2.7 |

| Prefer occasional phone contact self-directed | 105 | 27.5 | 25 | 29.8 | 23 | 24.7 | 24 | 25.3 | 33 | 30.0 |

| Prefer occasional phone contact self- and therapist-directed | 194 | 50.8 | 41 | 48.8 | 48 | 51.6 | 50 | 52.6 | 55 | 36.7 |

| Prefer regular weekly phone call | 66 | 17.3 | 14 | 16.7 | 19 | 20.4 | 14 | 14.7 | 19 | 12.7 |

Note. NHWRQ = no homework reflection questionnaires; HWRQ = homework reflection questionnaires; WAI-SR = Working Alliance Inventory – Short Revised.

Few patients reported negative or adverse events resulting from participation in iCBT (12.0%, n = 46). Of the patients who reported negative effects, 43.5% (n = 20) reported an increase of existing symptoms, 30.4% (n = 14) reported negative emotions, 13.0% (n = 6) reported negative thoughts about self, time lost, or participation in the course, and 13.0% (n = 6) did not provide a specific reason. No main effects or interactions were found (p range: .69–.87).

In terms of preferences for contact, patients' who received 1W support were more likely to prefer 1W contact than patients who received 2W support (67.2% vs. 37.1%; Wald's χ2 (1, N=382) = 34.12, p < .001). The most common preference for frequency of phone calls was ‘occasional phone contact, self- and or therapist-directed’ (50.8%, n = 194) with no main effects or interactions were found (p range: .11–.58).

3.7. Therapist timing

The amount of time that therapists spent providing weekly support is reported in Table 7. Offering support 2W took significantly more time (M: 172; SD: 74 min) than 1W support (M: 124; SD: 54 min), F (1, 589) = 81.92, p < .001. No other differences were found (p = .36).

Table 7.

Means and standard deviations for therapist time (in minutes) spent on patients per week by group.

| All groups (N = 593) |

Once-weekly support (n = 292) |

Twice-weekly support (n = 301) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HWRQ (n = 150) |

NHWRQ (n = 142) |

HWRQ (n = 151) |

NHWRQ (n = 150) |

|||||||

| Min–max | Mean (SD) | Min–max | Mean (SD) | Min–max | Mean (SD) | Min–max | Mean (SD) | Min–max | Mean (SD) | |

| Week 1 | 0–113 | 22 (17) | 0–113 | 18 (14) | 1–104 | 20 (18) | 0–76 | 24 (17) | 0–104 | 24 (17) |

| Week 2 | 0–93 | 17 (14) | 0–63 | 15 (11) | 0–63 | 13 (11) | 0–93 | 21 (16) | 0–77 | 20 (15) |

| Week 3 | 0–56 | 17 (11) | 0–44 | 13 (9) | 0–54 | 14 (10) | 0–56 | 19 (13) | 0–56 | 21 (13) |

| Week 4 | 0–62 | 18 (13) | 0–55 | 14 (10) | 0–51 | 14 (10) | 0–62 | 21 (15) | 0–62 | 21 (14) |

| Week 5 | 0–130 | 18 (15) | 0–72 | 15 (13) | 0–72 | 14 (12) | 0–130 | 21 (17) | 0–72 | 21 (15) |

| Week 6 | 0–100 | 17 (14) | 0–94 | 15 (13) | 0–64 | 14 (12) | 0–73 | 18 (13) | 0–100 | 22 (17) |

| Week 7 | 0–75 | 16 (12) | 0–57 | 13 (10) | 0–58 | 13 (9) | 0–75 | 20 (14) | 0–58 | 19 (14) |

| Week 8 | 0–117 | 16 (15) | 0–117 | 14 (13) | 0–46 | 10 (8) | 0–103 | 20 (17) | 0–116 | 21 (16) |

| Week 9 | 0–57 | 7 (10) | 0–54 | 9 (11) | 0–46 | 8 (10) | 0–57 | 5 (11) | 0–43 | 6 (9) |

| Overall total | 28–396 | 148 (69) | 31–309 | 126 (57) | 28–264 | 122 (50) | 29–396 | 170 (72) | 33–389 | 175 (76) |

3.8. Qualitative analysis

Results of the qualitative analysis of therapist perceptions of HWRQs and 2W support are presented in Table 8. Benefits and challenges of each approach were noted by therapists. Benefits to HWRQ included a perceived increase in patient engagement and patient learning as well as increased therapist knowledge of patients and increased therapist efficiency in composing emails, especially among patients who sent brief or few emails to therapists. Challenges to HWRQ, however, were also noted including composing emails when the HWRQ was redundant with patient emails, ambiguous or left incomplete. At the end of the trial, a location difference was found such that those employed by the iCBT clinic (n = 4) expressed an interest in having patients complete HWRQs while therapists employed by the community clinic did not (n = 5). Both groups, however, preferred to reserve judgement pending research findings. Opinions related to HWRQ did not change over time.

Table 8.

Patient and therapist benefits and challenges related to homework reflection questionnaires and twice-weekly support.

| Homework reflection questionnaires | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | Subtheme | Description | |

| Patient benefits | Encourages and thus increases patient engagement | Encourages patient engagement and seems to be a more comfortable way for some patients to share | “So you're giving them more encouragement because of [their reflection answers], more praise but also more psychoeducation because I think it takes a certain amount of like bravery or level of comfort to write a specific email to your therapist that not all clients would feel comfortable with…But if a survey is asking you for an example that they've been struggling with and have a question about, it lets them ask the question without having to go outside of their comfort zone to ask the question. So I think for those maybe shyer, less communicative people, it gives them that avenue to do so without actually doing so.” Therapist 3 |

| Fosters and expedites patient learning | Encourages patients to share their experiences which fosters learning | “I think it facilitates understanding, especially if they are taking the time to fill in those text boxes where they write out their cycle of symptoms and if they're able to identify maybe two of the three of the cycle, then it's providing some – doing some facilitating of understanding of what that third cycle might look like.” Therapist 6 | |

| Therapist benefits | Increases knowledge of patient | Encourages patients to share experiences increasing therapist knowledge of patient | “I like having that concrete evidence they've been doing it and get a sense of where their thinking is at, what their concerns are. So I like that. I like reflecting that back and asking questions about it.” Therapist 1 |

| Increases efficiency | Provides easy way to review information reducing therapist time to compose emails | “It saves me time. I can read their answers and always pull something out to create my next question for them. It makes things faster for me.” Therapist 3 | |

| Therapist challenges | Managing redundant information | Requires therapist to manage information that is redundant with patient emails | “I find that if somebody is going to take the time to fill in the reflection, they're already sent me a detailed email anyway.” Therapist 4 |

| Managing ambiguous information | Requires therapist to make interpret ambiguous information | “I find that some of the questions in the reflection leave me more confused than clear, you know what I mean, especially if how they fill out, ‘I moderately did not understand’ … I'm like okay, did you get it or was it a struggle?” Therapist 6 | |

| Managing incomplete information | Requires therapist to manage incomplete information | “I find that probably only I would say a third of the clients are taking time– like really fill in the typed part [comment boxes]. I've had so few clients enter info into the dialogue boxes.” Therapist 6 | |

| Twice-weekly support | |||

| Patient benefits | More timely and personal care | More timely and personal emails for patients who email more than once a week | “For the clients that are using the twice a week condition and messaging in between contacts, you do utilize that second message to respond to questions, and [are] better able to quickly address those concerns instead of waiting a week to respond.” Therapist 3 |

| Increased engagement | Increases patient engagement with treatment | “What I have found is people who are engaged may become more engaged with twice a week contact … if they're expressing struggle, there is psychoeducation that's happening in those [second] emails and it's giving them direction to the additional resources and linking that with how they can – like how within their situation they can benefit from reviewing different content within the course.” Therapist 6 | |

| Patient challenges | Overwhelmed with support | Number of emails perceived to overwhelm some patients | “I actually have 2 clients now within the past couple of weeks in twice a week, have said I want to respond to all the questions that you have for me but it takes me a while so I'll just answer these 2 because they come to like 4 messages with 4 questions each and they don't know which ones to answer, which ones are most important.” Therapist 1 |

| Unnecessary support | Number of emails perceived as unnecessary by some patients | “I had a twice a week client and when they completed the treatment and satisfaction, the preferred level of contact was once a week. They did their work, they did write to me. I felt like everything went just fine; however, they said once [a week] was enough. So that is an example of direct feedback I have received.” Therapist 1 | |

| Therapist benefits | Increased connection to patients | Improves connection with some patients | “I think a huge advantage is just as a therapist, I feel like I know my clients better because I'm reviewing their work or whatever, their profile, twice a week, then it's doubled and I'm looking at the stuff. So I just feel like I have a stronger connection because of that. Whether I do or not, I feel like I do because I see them more, I see their name more and their process and I read their stuff more.” Therapist 3 |

| Increased recall of patient information improving efficiency | Improves recall of patient information and thus therapist efficiency | “I feel like there's opportunity for more familiarity. When it's once a week, I have to read through it and try to remember what we were talking about more so, but with twice a week it's just on my mind more consistently so I need less review time because I know what's in the note because I've already read it twice this week or whatever it may be.” Therapist 1 | |

| Therapist challenges | Therapist burden related to unpredictable heavier workload | Overwhelms/burdens therapist because of frequency/length of patients emails and difficulty predicting time needed to deliver care | “I found initially when we first started, this is easy, this is just to let you know I checked your progress, and you've been online so good. Three sentences, a minute, done. But as the weeks went on, I hadn't budgeted enough time for it and I was really struggling to get through because all of a sudden I was feeling there was all this engagement and long pages. I'm scrolling through messages from clients and I was quite overwhelmed by it actually because I hadn't anticipated having that big of a second, but I mean it's levelled off now and I can just budget enough time now.” Therapist 2 |

| Therapist discomfort with providing support when it is perceived as unwanted | Creates therapist discomfort when emailing patients who are perceived to want less therapist support | “When they are really disengaged I don't like the twice a week because I feel like I'm annoying them. Do this, please do it. Like over and over and over. I feel like I'm pestering them.” Therapist 1 | |

| Organization challenges | Increases need to manage missed contacts | Increases need to manage therapists missing planned patient contact related to holidays or sick time (16 vs. 8 planned contacts) | “Well in line with this and making up days, challenged with say vacations for twice a week, it's a lot of contacts missed, over a week. Not so bad if it's a one week vacation, but 2 weeks that's a lot of contacts missed. It's a quarter of the course.” Therapist 3 |

| Reduces number of patients treated | Reduces clinic capacity to treat patients as therapists need more time to provide support twice-weekly | “People [therapists] book themselves in anticipation of both those contacts being lengthy contacts… So regardless of whether or not they actually need the time for the second contact, because they don't know what that's going to look like, they reduce their availability because they potentially could have a whole caseload that is contacting them with problems on the same day.” Supervisor 1 | |

In terms of 2W support, therapists perceived 2W support as resulting in more timely and personal care for patients and improving patient engagement. They described offering 2W support as often being more satisfying to deliver in terms of connecting with patients and taking less time to recall patient information. Challenges related to 2W support were also noted and included perceiving many patients to be overwhelmed with the amount of support offered or finding 2W support unnecessary. Further challenges included perceptions that offering 2W resulted in an increased and unpredictable workload as well as discomfort related to having to provide this level of support when they perceived 2W as unwanted by patients. Of note, therapists in the iCBT clinic expressed that 2W support was preferable to a one-business-day response to patient emails which was trialed in a previous study (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2020). Supervisors identified organizational challenges related to offering support 2W including a greater likelihood of having to manage therapists missing patient contacts (e.g., due to vacation or sick time) and also having reduced capacity to offer patients iCBT in order to accommodate the increased time therapists needed to deliver 2W support. Five out of nine therapists reported that the benefits of 2W support were not greater than 1W support, with therapists who preferred 2W support all employed by the community clinic.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this factorial randomized controlled trial was to contribute to pragmatic knowledge of iCBT in routine practice by examining the potential benefits for patients and therapists of: 1) having patients complete HWRQ versus NHWRQ at the beginning of each lesson; 2) offering 2W versus 1W therapist support; and 3) the interaction between the two factors. It was hypothesized that patients in the HWRQ condition and those receiving 2W support would have higher levels of engagement, experience greater reductions in symptoms, and report more positive treatment experiences. It was also hypothesized that therapists would have more positive experiences with using the HWRQ and offering 2W support.

4.1. Patient engagement, outcomes and treatment experiences