Abstract

Study Design:

Retrospective case series.

Objective:

Little is known about operative management of traumatic spinal injuries (TSI) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). In patients undergoing surgery for TSI in Tanzania, we sought to (1) determine factors involved in the operative decision-making process, specifically implant availability and surgical judgment; (2) report neurologic outcomes; and (3) evaluate time to surgery.

Methods:

All patients from October 2016 to June 2019 who presented with TSI and underwent surgical stabilization. Fracture type, operation, neurologic status, and time-to-care was collected.

Results:

Ninety-seven patients underwent operative stabilization, 23 (24%) cervical and 74 (77%) thoracic/lumbar. Cervical operations included 4 (17%) anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate, 7 (30%) anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest graft and plate, and 12 (52%) posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass screws. All 74 (100%) of thoracic/lumbar fractures were treated with posterolateral pedicle screws. Short-segment fixation was used in 86%, and constructs often ended at an injured (61%) or junctional (62%) level. Sixteen (17%) patients improved at least 1 ASIA grade. The sole predictor of neurologic improvement was faster time from admission to surgery (odds ratio = 1.04, P = .011, 95%CI = 1.01-1.07). Median (range) time in days included: injury to admission 2 (0-29), admission to operating room 23 (0-81), and operating room to discharge 8 (2-31).

Conclusions:

In a cohort of LMIC patients with TSI undergoing stabilization, the principle driver of operative decision making was cost of implants. Faster time from admission to surgery was associated with neurologic improvement, yet significant delays to surgery were seen due to patients’ inability to pay for implants. Several themes for improvement emerged: early surgery, implant availability, prehospital transfer, and long-term follow-up.

Keywords: spine trauma, spinal fractures, traumatic spinal cord injury, East Africa, Tanzania, global neurosurgery, global surgery

Introduction

Traumatic spinal injury (TSI), including fractures to the spinal column and spinal cord injury (SCI), represents a global disease burden, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).1,2 A recent systematic review concluded that the burden of TSI was 1.6 times higher in LMICs than high-income countries, with an annual incidence of 13 cases per 100 000 people.2,3 Operative treatment of TSI remains a scarce resource offered only by select centers.

Clinical conditions after SCI include temporary or permanent paralysis, sensory loss, autonomic imbalance, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Acute mortality rates from TSI in sub-Saharan Africa range from 18%4 to 25%,3 compared with close to zero in more resourced settings.5 In their series of 288 patients with SCI from Tanzania, Moshi and colleauges3 highlighted the added morbidity of post-SCI complications, such as pressure ulcers (20%) and respiratory dysfunction (15%), leading to an average hospital stay of over 2 months. Despite improvements in TSI management, resource-constrained settings have not yet benefitted from this progress to the same extent as more developed countries.6-8

Although neurosurgery has been developing in East Africa since the 1940s, it remains tertiary and expensive.9 Both stabilization techniques and time to surgery for spinal trauma are largely unreported. Such information would not only allow for improvement in operative decision making but also provide direction for future policy, government collaboration, and research initiatives critical to mitigating the burden of spinal trauma. To address this need, we describe the operative management of patients undergoing surgical stabilization for traumatic spinal injuries at a major LMIC hospital in Tanzania in order to: (1) assess the factors involved in the operative decision-making process, specifically implant availability and surgical judgment; (2) report neurologic outcomes; and (3) evaluate time to surgery. If implant availability is the principal driver of decision making, results from the current study will allow us to conclude if current practices are adequate or insufficient given the limited resources. Furthermore, knowing detailed operative information will facilitate planning for future implant needs.

Methods

Study Design and Clinical Setting

We conducted a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from the Muhimbili Orthopaedic Institute (MOI), a major referral hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. MOI houses approximately 120 general ward beds and 16 intensive care unit (ICU) beds. The local institutional review board approved the current study and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patient Identification

All patients who underwent surgical intervention for TSIs from October 2016 to June 2019 (32 months) were included. Exclusion criteria consisted of those who underwent decompression only (laminectomy without instrumentation or fusion), were <14 years old, sustained a concomitant brain injury, or underwent an operation >4 months from the time of injury. This case series represents an extension of a previously published cohort.10

Clinical and Operative Data

Several demographic and injury-specific data points were collected, including age, gender, and mechanism of injury. Injury levels were categorized according to prior studies.11 Owing to difficulty in deciphering the extent of decompression, this variable was kept binary (yes/no). Insurance status was classified as public (had to provide all funds prior to receiving hospital services) or private (no additional funds required to receive hospital services).

Classification of Fractures, Neurologic Status, Surgery, and Timing

Fractures were classified according to the thoracolumbar AO classification,12 a system used to classify spine trauma with good reliability,13 along with the addition of descriptive terms for each injury. To decipher trends in management, fractures of similar patterns were grouped by mechanism and amount of listhesis/translation. Listhesis was defined as: I = 25%, II = 50%, III = 75%, IV = 100%. Neurologic exams were obtained on admission and discharge according to the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale.14 One of 4 surgeries was performed: (1) anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate (ACDF), (2) anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest graft and plate (ACC), (3) posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass screws (PCLF), and (4) posterolateral thoracic or lumbar laminectomy and fusion with pedicle screws (PLF). Autograft was used in the majority of cases, either local or iliac crest harvesting. Time in days was recorded during the following points: injury to admission, admission to operating room (OR), OR to discharge, and total length of stay (LOS).

Guideline Comparison

For cervical TSI, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons (AANS/CNS) Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cervical Spine and Spinal Cord Injuries was used.15 For thoracic/lumbar injuries, the corollary document was used.16,17 Three additional parameters were used to assess the adequacy of each construct. First, short-segment stabilization was defined as 1 level above and 1 level below the injured level. Any construct more than 1 level above or below was not considered short-segment stabilization. Second, each construct was evaluated if the upper or lower instrumented vertebrae (UIV/LIV) involved the injured level. If the UIV/LIV involved a fractured level, or a level with facet or disc disruption, this variable was recorded as positive. For example, a patient with T6/7 listhesis and a T7 fracture that underwent T6-8 fusion would be positive because T6 was both injured and the UIV. Third, constructs that stopped at a junctional level (C7, T1, T12, L1) was recorded. Since postoperative imaging was often not obtained due to cost, imaging parameters such as change in kyphosis, reduction, and decompression could not be assessed.

Statistical Analysis

All continuous data was presented as mean (SD) and/or median (range), whereas all count data was presented as n (%). Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess predictors of improvement in neurologic function. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess predictors of timing. Significance was considered at an alpha of .05. All statistical analyses were performed in STATA version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient Cohort

On initial review, 114 patients with TSI underwent surgery. Two underwent decompression only without stabilization. Of the remaining 112 patients, missing data existed for 4 patients regarding level of injury, 9 patients regarding operative details, and 2 patients regarding postoperative outcomes. These 15 patients were excluded, leaving 97 patients with complete data. Of the 97 patients with TSI who underwent surgical stabilization, 25 (26%) sustained cervical injuries and 72 (74%) sustained thoracic/lumbar injuries (Table 1). Almost half of patients (48%) presented with complete injuries (ASIA A). All but 2 patients (98%) underwent concomitant decompression.

Table 1.

Demographics, Injury, and Operative Information (N = 97).

| Age, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 34.7 (11.7) |

| Median, (range) | 32 (14-74) |

| Male, n (%) | 78 (80) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |

| Public | 84 (86) |

| Private | 13 (13) |

| Mechanism, n (%) | |

| Motor vehicle accident | 30 (31) |

| Motorcycle | 10 (10) |

| Pedestrian | 7 (7) |

| Fall | 32 (33) |

| Blunt object | 16 (16) |

| Other | 2 (2) |

| AO fracture type, n (%) | |

| A | 3 (31) |

| B | 14 (14) |

| C | 53 (55) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| Axial cervical spine | 1 (1) |

| Subaxial cervical spine | 22 (23) |

| Cervicothoracic spine | 0 (0) |

| Thoracic spine | 34 (35) |

| Thoracolumbar | 13 (13) |

| Lumbar | 27 (28) |

| Neurologic status, n (%) | |

| Complete (ASIA A) | 47 (48) |

| Incomplete (ASIA B-D) | 37 (38) |

| Intact (ASIA E) | 13 (13) |

| Total operations, n (%) | |

| Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate | 4 (4) |

| Anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest graft and plate | 7 (7) |

| Posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass screws | 12 (12) |

| Posterolateral thoracic/lumbar laminectomy and fusion with pedicle screws | 74 (76) |

Operative Decision Making

Operative decision making depended on many factors. Public patients without insurance were forced to pay for their own implants, which often delayed surgery and limited the size of each construct. If a family could only pay for 4 screws, the surgeon was forced to treat the injury with these resources only. Overall, operative decision making—type of surgery, extent of construct, and timing—was based on 4 components: (1) resources available, (2) the patient’s ability to pay for implants, (3) clinical status, and (4) surgeon preference. Importantly, no formal spine trauma protocol was followed during the duration of this study.

Cervical

A total of 23 cervical fractures were treated with 4 (17%) anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate (ACDF), 7 (30%) anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest graft and plate (ACC), and 12 (52%) posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass screws (PCLF; Table 2). Tricortical iliac crest autograft iliac crest autograft were used for both ACDF and ACC. With respect to guidelines management, the AANS/CNS document states, “…either anterior or posterior fixation and fusion is acceptable in patients not requiring a particular surgical approach for decompression of the spinal cord.”15 No preference is made of short- or long-segment stabilization. Thus, as long as all patients were appropriately decompressed, we can conclude that the guidelines were followed based on the available information, albeit without postoperative imaging. Additionally, 22 (96%) of fractures were treated with short-segment stabilization, and 17 (74%) had the UIV/LIV involve the injured level. Fourteen (61%) constructs stopped at the cervicothoracic junction.

Table 2.

Cervical Fracture Management.

|

Level | Injury | N | Case No. & Surgery |

| O-C2 | C2 pars fracture | 1 | 1. O-C2 PCLF | |

| C3/4 | C3/4 listhesis I + C4 fracture | 1 | 2. C3-4 PCLF | |

| C4/5 | C4 + C5 burst fractures | 1 | 3. C4-6 PCLF | |

| C4/5 listhesis I | 1 | 4. C4-6 PCLF | ||

| C4/5 listhesis II | 1 | 5. C3-5 PCLF | ||

| C5/6 | C5/6 listhesis I | 2 | 6. C5-6 ACDF 7. C4-6 PCLF |

|

| C5/6 listhesis II | 2 | 8. C5 corpectomy, C4-6 plate 9. C6 corpectomy, C5-7 plate |

||

| C5/6 listhesis II + C5 or C6 fracture | 3 | 10. C6 corpectomy, C5-7 plate 11. C6 corpectomy, C5-7 plate 12. C4-6 PSF |

||

| C6 burst fracture | 2 | 13. C6 corpectomy, C5-7 plate 14. C5-7 PCLF |

||

| C6/7 | C6/7 listhesis I | 2 | 15. C6-7 ACDF 16. C6-7 ACDF |

|

| C6/7 listhesis II | 2 | 17. C6-7 ACDF 18. C5-7 PCLF |

||

| C6/7 listhesis III-IV | 4 | 19. C5-7 PCLF 20. C5-7 PCLF 21. C5-7 PCLF |

||

| C6/7 listhesis III + C7 fracture | 1 | 22. C6-7 PCLF | ||

| C7 burst fracture | 1 | 23. C7 corpectomy, C6-T1 plate |

Abbreviations: ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate; PCLF, posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass screws.

In assessing trends in management, the 6 cases of grade I listhesis were treated with 3 ACDFs and 3 PCLFs. All cases of grade II listhesis were treated with either ACC or PCLF, except for 1 ACDF (case 17). All cases of grade III-IV listhesis were treated with a 2-level fusion except for one case, which was treated with a 1-level fusion (case 22). All burst fractures were treated with either ACC or PCLF. No construct crossed the cervicothoracic junction. The one craniocervical spine injury, a C2 pars fractures, was treated with occipitocervical fusion.

Thoracic/Lumbar

A total of 74 thoracic/lumbar fractures (100%) were all treated with posterior thoracic or lumbar laminectomy and fusion with pedicle screws (PLF; Tables 3 and 4). With regard to guidelines management, the AANS/CNS document states, “…physicians may use an anterior, posterior, or a combined approach as the selection of approach does not appear to impact clinical or neurological outcomes.”16 Similar to the cervical guidelines, no preference is made of short- or long-segment stabilization, allowing us to conclude that as long as an appropriate decompression was accomplished, the guidelines were followed based on the available information, albeit without postoperative imaging. Additionally, 61 (82%) of fractures were treated with short-segment stabilization, and 43 (58%) had the UIV/LIV involve the injured level. Forty-six (62%) constructs stopped at the thoracic/lumbar junction.

Table 3.

Thoracic Fracture Management.

|

Level | Injury | N | Case No. & Surgery |

| T3/4 | T4 chance fracture | 1 | 24. T3-5 PLF | |

| T3 + T4 burst fractures | 1 | 25. T1-5 PLF | ||

| T4 burst fracture | 2 | 26. T3-5 PLF 27. T3-5 PLF |

||

| T4 burst fracture + T3/4 listhesis I | 1 | 28. T3-5 PLF | ||

| T4 burst fracture + T3/4 listhesis III-IV | 1 | 29. T3-4 PLF | ||

| T4/5 | T5 burst fracture + T4/5 listhesis III-IV | 1 | 30. T3-7 PLF | |

| T5/6 | T6 burst fracture + T5/6 listhesis I | 1 | 31. T4-6 PLF (left only) | |

| T6/7 | T6 – T9 burst fractures | 1 | 32. T7-9 PLF | |

| T6 burst fracture + T6/7 listhesis II | 1 | 33. T5-7 PLF | ||

| T7 burst fracture + T6/7 listhesis I | 1 | 34. T6-9 PLF | ||

| T7/8 | T8 burst fracture + T7/8 listhesis I | 1 | 35. T7-8 PLF | |

| T8/9 | T8 wedge-compression fracture | 1 | 36. T7-9 PLF | |

| T8 burst fracture + T8/9 listhesis II | 1 | 37. T8-10 PLF | ||

| T8/9 listhesis I | 1 | 38. T8-10 PLF | ||

| T9/10 | T9/10 listhesis II | 1 | 39. T8-10 PLF | |

| T10/11 | T10 wedge-compression fracture | 1 | 40. T9-12 PLF | |

| T10/11 listhesis II | 1 | 41. T9-11 PLF | ||

| T11/12 | T11/12 listhesis II | 4 | 42. T11-12 PLF 43. T11-L1 PLF 44. T11-L1 PLF 45. T12-L1 PLF |

|

| T11 burst fracture + T11/12 listhesis III-IV | 1 | 46. T11-L1 PLF | ||

| T12 chance fracture | 1 | 47. T11-L1 PLF | ||

| T12 burst fracture | 1 | 48. T11-12 PLF | ||

| T12 burst fracture + T11/12 listhesis I | 6 | 49. T10-L2 PLF 50. T11-L1 PLF 51. T11-L1 PLF 52. T11-L1 PLF 53. T11-L1 PLF 54. T11-L1 PLF |

||

| T12 burst fracture + T11/12 listhesis II | 3 | 55. T11-L2 PLF 56. T11-L2 PLF 57. T11-L2 PLF |

||

| T12/L1 | T12/L1 listhesis II | 2 | 58. T11-L1 PLF 59. T11-L2 PLF |

Abbreviation: PLF, posterolateral fusion.

Table 4.

Lumbar Fracture Management.

|

Level | Injury | N | Case No. & Surgery |

| L1/2 | L1 wedge-compression fracture | 3 | 60. T12-L2 PLF 61. T12-L2 PLF 62. T12-L2 PLF |

|

| L1 chance fracture | 2 | 63. T10-L2 PLF 64. T12-L2 PLF |

||

| L1 chance fracture + L1/2 listhesis I | 1 | 65. L1-3 PLF | ||

| L1 burst fracture + no listhesis | 11 | 66. T11-L1 PLF 67. T12-L2 PLF 68. T12-L2 PLF 69. T12-L2 PLF 70. T12-L2 PLF 71. T12-L2 PLF 72. T12-L2 PLF 73. T12-L2 PLF 74. T12-L2 PLF 75. T12-L2 PLF 76. T12-L2 PLF |

||

| L1 burst fracture + T12/L1 listhesis I | 4 | 77. T11-L2 PLF 78. T12-L2 PLF 79. T12-L2 PLF 80. T12-L2 PLF 81. T12-L2 PLF |

||

| L1 burst fracture + T12/L1 listhesis II | 4 | 82. T12-L2 PLF 83. T12-L2 PLF 84. T12-L2 PLF |

||

| L2 wedge-compression fracture + L1/2 listhesis I | 1 | 85. L1-2 PLF | ||

| L2 burst fracture + L1/2 listhesis I | 2 | 86. L1-2 PLF 87. L1-3 PLF |

||

| L2 burst fracture + L1/2 listhesis II | 3 | 88. L1-3 PLF 89. L1-3 PLF 90. L1-3 PLF |

||

| L2 burst fracture + L1/2 listhesis III-IV | 2 | 91. L1-3 PLF 92. T12-L4 PLF |

||

| L2/3 | L2 + L3 burst fractures | 1 | 93. L1-4 PLF | |

| L3 burst fracture + no listhesis | 3 | 94. L2-4 PLF 95. L2-4 PLF 96. L2-4 PLF |

||

| L3 burst fracture + L2/3 listhesis II | 1 | 97. L1-3 PLF |

Abbreviation: PLF, posterolateral fusion.

In assessing trends in management, the most common fracture types were L1 burst fracture without listhesis (n = 11), most of which were treated with T12-L2 PSF, except for one T11-L2 PSF. Second most common was T12 burst fractures with grade I listhesis, most of which were treated with T11-L2 PSF except for one longer construct of T10-L2 PSF. Few long segment constructs were utilized, which included 7 (9.5%) 3-level fusions and 4 (5.4%) 4-level fusions. The most severe fractures of grade III-IV listhesis were treated with T3-4 PSF (case 29), T3-7 PSF (case 30), T11-L1 PSF (case 46), L1-3 PSF (case 91), and T12-L4 PSF (case 92).

Neurologic Outcomes

Five patients had incomplete postoperative ASIA assessments—3 died and 2 were missing. Of the remaining 92 patients, 2 (2%) worsened by 1 ASIA grade (both B to A); 74 (80%) were stable; and 16 patients improved (17%), 12 (13%) by 1 grade, and 4 (4%) improved by 2 grades (Table 5, panels A and B). The three patients that died postoperatively during hospitalization included were C5/6 lesions. In assessing predictors of ASIA improvement, while controlling for age, gender, insurance status, and operation, multivariate logistic regression revealed that time from admission to OR was a small but significant predictor of an improved ASIA grade (odds ratio = 1.04, P = .012, 95%CI = 1.01-1.08; Table 5, panel C).

Table 5.

Neurologic Outcomes: (A) Changes in ASIA Score From Admission to Discharge; (B) Categorization ASIA Score Changes; (C) Predictors of Neurologic Improvement Logistic Regression Analysis.

| A. Changes in ASIA Score From Admission to Discharge | ||||||||||||

| ASIA on admission, n (%) | Total | 42 (46) | 13 (14) | 9 (10) | 11 (12) | 17 (18) | 92 (100) | |||||

| E | — | — | — | — | 13 (76.7) | 13 (14) | ||||||

| D | — | — | — | 8 (72.7) | 3 (17.7) | 11 (12) | ||||||

| C | — | — | 2 (22.2) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (5.9) | 5 (5) | ||||||

| B | 2 (4.8) | 11 (84.6) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (9.1) | — | 19 (21) | ||||||

| A | 40 (95.2) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (22.2) | — | — | 44 (48) | ||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | Total | |||||||

| ASIA on Discharge, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| B. Categorization of ASIA Score Changes | ||||||||||||

| Worsened, n (%) | Stable, n (%) | Improved, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Cervical (n = 20) | 1 (5.0) | 16 (80.0) | 3 (15.0) | |||||||||

| Thoracolumbar (n = 72) | 1 (1.4) | 58 (81.9) | 13 (18.1) | |||||||||

| Total (n = 92) | 2 (2.2) | 74 (80.4) | 16 (17.4) | |||||||||

| C. Predictors of Neurologic Improvement | ||||||||||||

| Univariate Logistic Regression | Multivariate Logistic Regression | |||||||||||

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | ||||||||

| Age (years) Young <30 (n = 36) Old ≥30 (n = 61) |

1.36 (0.42, 4.3) | .604 | — | — | ||||||||

| Gender Male (n = 78) Female (n = 19) |

0.68 (0.19, 2.42) | .548 | — | — | ||||||||

| Injury level Cervical (n = 23) Thoracic/Lumbar (n = 74) |

1.25 (0.32, 4.90) | .750 | — | — | ||||||||

| Insurance Public (n = 84) Private (n = 13) |

0.36 (0.04, 2.95) | .338 | — | — | ||||||||

| Operation ACDF/ACC/PCLF/PLF |

0.94 (0.47, 1.91) | .872 | — | — | ||||||||

| Time from admission to OR Continuous (days) |

1.03 (1.01, 1.07) | .011 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) | .012 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association; ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate; ACC, anterior cervical corpectomy with plate; PCLF, posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass screws; PLF, posterior thoracic or lumbar laminectomy and fusion with pedicle screw fixation; OR, operating room.

Timing

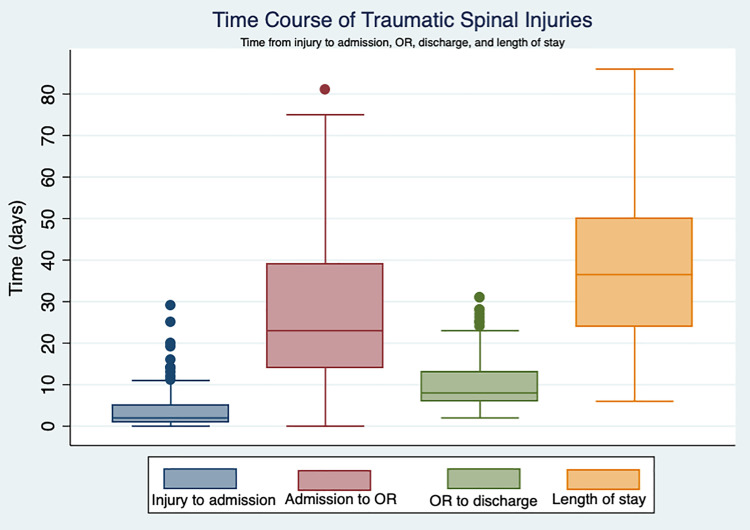

Timing of each phase of care was summarized (Table 6, Figure 1). Both cervical and thoracic/lumbar AANS/CNS guidelines concluded there was insufficient evidence on the effect of timing of surgical intervention on neurologic outcomes, “but it is suggested that ‘early’ surgery be considered an option…defined as <8 to <72 hours.” Thus, using the conservative estimate, we can cap these recommendations at 72 hours. Median time from admission to OR was 23 days, ranging from 0 to 81. A total of 4 patients (4.1%) were operated on within 72 hours of admission. Counting time from initial injury, 2 patients (2.1%) were operated on within 72 hours.

Table 6.

Time From Injury to MOI, MOI to OR, Time From OR to Discharge, and Total MOI LOS.

| Time From Injury to Admissiona (Days) | P b | Time From admission to OR (Days) | P b | Time From OR to Discharge (Days) | P b | Total LOS (Days) | P b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Median (range) Mean (SD) |

2 (0-29) 4.0 (5.4) |

— |

23 (0-81) 27.4 (17.8) |

— |

8 (2-31) 10.8 (7.1) |

— |

37 (6-86) 38.9 (18.1) |

— |

| Age in years, median (IQR) Young <30 (n = 36) Old ≥30 (n = 61) |

2 (1-4) 2 (1-6) |

.303 |

21 (13-36) 24 (14-40) |

.591 |

7 (6-12) 8 (7-14) |

.193 |

33 (21-43) 40 (26-50) |

.277 |

| Injury level, median (IQR) Cervical (n = 23) Thoracic/Lumbar (n = 74) |

2 (1-6) 2 (1-5) |

.718 |

16 (4-35) 25 (18-40) |

.010 |

11 (6-22) 8 (6-12) |

.248 |

36 (21-50) 37 (25-50) |

.521 |

| Operation, median (IQR) ACDF with plate Anterior corpectomy with plate Posterior cervical fusion Posterior thoracic/lumbar fusion |

0 (0-13) 1 (0-4) 3 (1-8) 2 (1-5) |

.378 |

21 (15-34) 10 (4-22) 13 (4-39) 25 (18-40) |

.051 |

21 (12-31) 6 (4-16) 9 (7-23) 8 (6-12) |

.055 |

47 (37-64) 24 (20-28) 40 (17-50) 37 (25-50) |

.220 |

| Insurance, median (IQR) Public (n = 84) Private (n = 13) |

3 (1-5) 1 (1-2) |

.287 |

25 (15-40) 18 (11-24) |

.084 |

8 (6-12) 13 (8-23) |

.026 |

39 (24-50) 31 (25-39) |

.283 |

| Neurologic, median (IQR) Complete/Intact (ASIA A/E) (n = 60) Incomplete (ASIA B-D) (n = 37) |

2 (1-5) 2 (0-5) |

.616 |

24 (14-34) 23 (14-45) |

.174 |

8 (7-13) 8 (5-14) |

.329 |

36 (24-48) 43 (27-57) |

.1625 |

Abbreviations: MOI, Muhimbili Orthopaedic Institute; OR, operating room; LOS, length of stay; ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate; ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association; IQR, interquartile range.

a One injury to MOI admission was a severe outlier (105 days) and removed from analysis, thus n = 96.

b All comparisons by nonparametric comparison of medians with Wilcoxon rank-sum test, except operation, which was Kruskal-Wallis test for comparison of more than 2 groups. Boldfaced P values indicate statistical significance (P < .05).

Figure 1.

Time course of traumatic spinal injuries.

Discussion

In a large cohort of traumatic spinal injury patients that underwent surgical stabilization from a major referral hospital in East Africa, we have described each fracture pattern with corresponding operative treatment, in addition to neurologic outcomes and timing of surgery. Short-segment stabilization was used in 86% of cases. While faster time from admission to surgery was associated with improved neurologic function, only 4% of patients underwent surgery within 3 days of admission, most commonly because of a patient’s inability to pay for instrumentation. The principal driver of operative decision making appeared to be cost of implants, leading to a high proportion of short-segment constructs and delays to surgery.

Surgical Details and Operative Decision Making

While surgery for traumatic spinal injury is performed in several LMICs, it remains sparse and carries great risk, as one study reported increased complications and mortality in patients undergoing surgery.18 Of the reports summarizing TSI in LMICs, little to no operative information is provided in series from India,18,19 Ghana,5 Nigeria,20 and Tanzania.3 One of the few studies reporting operative details was conducted by Choi and colleagues11 from Cambodia, in their series of 62 TSI patients who underwent surgery, which included ACDF, ACC, cervical laminoplasty, and posterior thoracic/lumbar stabilization with interspinous wiring, pedicle screws, and Luque rod fixation.

The current series described a total of 4 surgeries—anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest graft and plate, posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion, and posterolateral thoracic/lumbar fusion thoracic/lumbar fusion. Stabilization methods included tricortical iliac crest autograft and anterior cervical plating with screws, in addition to lateral mass and pedicle screws with rods. Short-segment stabilization was used in 86% of cases and almost two-thirds of all constructs had the upper and lower instrumented vertebrae involve an injured level or stopped at a junctional level. In terms of AANS/CNS guideline management, we can cautiously say that all fractures were decompressed and stabilized at or across the injured segment, thus the guidelines were appropriately followed. However, this conclusion is made cautiously for two reasons. First, because of cost, postoperative imaging was not available on all patients, thus parameters such as kyphosis, fracture reduction, and decompression could not be evaluated. Second, without long-term follow-up, construct durability could not be adequately assessed.

Equally important to operative details is the process of how each operation was planned, which was directly linked to the dearth of financial resources. Choi and colleagues11 reserved pedicle screws for less severe injuries that only required 1 level above and below, whereas Luque rod fixation was used for 2 levels above and below. In a Nigerian series of 17 patients undergoing surgery for TSI by Nwanko et al,20 strut grafts and interspinous wiring were used to minimize costs, yet 43% of the remaining 68 patients had indications for surgery but did not undergo operative treatment due to their inability to pay. Similarly, in our study, publicly insured patients (86%) had to garner funds for implants, which dictated construct size and timing of surgery. This may have led to undertreating complex fractures, as 5 severe fractures, with grade III-IV listhesis, could only be treated with short-segment constructs. Risk is undertaken with short-segment constructs, when the upper and lower instrumented vertebrae involve the fractured levels, and when constructs end at junctional levels. These risks could be easily avoided with improved access to implant availability, of which a study is currently ongoing at MOI in 2019-2020.

Neurologic Outcomes

In our series, 17% improved by at least 1 ASIA grade after surgery. Compared with higher income countries and clinical trials, this rate was expectedly lower. Austrian and Korean studies have reported a 31% and 47% improvement rate, respectively.21,22 A large report of 1410 SCI patients from a Canadian spinal cord injury registry showed that patients with incomplete injuries who underwent surgery within 24 hours improved by 6.3 motor points compared with those who underwent late surgery.23 Interestingly, a smaller US study showed a benefit to ultra-early decompression, where cervical SCI patients undergoing surgery within 8 hours improved significantly more than those in the 8- to 24-hour range—45.5% improvement by 2 ASIA grades versus 10% (P = .017).24 Though promising, these results from high-income countries should not be directly applied to an LMIC setting due to obvious environmental differences. In Nigeria, Nwankwo et al20 reported neurologic improvement in 53% of patients undergoing surgery; however, they operated on only 1 ASIA A patient (6%) compared to 48% in our series. Similar to our results, Lofven et al8 from Botswana reported an ASIA improvement rate of 16%. While a large study from Iran of 431 TSI patients reported early surgery (<48 hours) in 41% of patients, rates of neurologic improvement were unfortunately not included. Taken in the context of similar LMIC settings, our rate of neurologic improvement is acceptable, yet room for improvement exists.

Timing

Given the finding that 4% of patients went to the OR within 3 days of admission and median time from admission to OR was 23 days (range 0-81), the focus of our future work is obvious. The Surgical Timing in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (STASCIS) trial, a prospective, multicenter effort, showed that surgery in <24 hours lead to improved recovery,25 and an international survey of 971 spine surgeons noted that over 80% preferred to decompress the spinal cord within 24 hours.26 The commonly accepted guideline of <24 hours was simply not possible in our series, and moreover, factors regarding the LMIC setting make this a starkly different discussion than higher income countries. Our center is not unique in this regard. Lofven et al27 in Botswana reported a median time from injury to surgery of 12 days. Our results did reveal that cervical patients were able to go to surgery sooner than thoracic/lumbar patients, which is promising. In any case, both lack of financial resources and available instrumentation were the major culprits for delay.

Future Recommendations

TSI is a major health care burden that primarily affects young, active, males, leading to loss of manpower, decreased productivity, and death, all with economic implications.6,28 We offer the following recommendations:

Implementation of a spine trauma protocol: A triage system where incomplete SCI patients are prioritized for the OR should be implemented. Efforts to implement a “Spine Trauma Protocol” at MOI are currently ongoing.

Spinal implant availability: Spinal implants should be available for all patients, regardless of their ability to pay. Arrangements can be made through hospital policies, insurance agreements, donations, and government funding.

Avoid prehospital delays from injury to admission: Given the few neurosurgical centers that offer surgery for TSI in sub-Saharan Africa, this information should be widely disseminated to transferring emergency services to avoid unnecessary stays at outside facilities.

Track long-term follow-up of constructs: Patient follow-up, especially for poor laborers in remote villages, is difficult. To understand the efficacy of short-segment fixation, local follow-up can be written for simple postoperative x-rays to be obtained by local practitioners.

Limitations

This study is not without limitation. First, no long-term follow-up was included, which prevents us from making inferences regarding construct durability. Second, postoperative imaging was not routinely obtained due to cost, which made it difficult to determine if the guidelines were followed, which further cautions our interpretation. Third, neurologic evaluations were only made at time of discharge, and no opportunity for follow-up improvement or decline was possible. Fourth, though this case series was drawn from a prospectively maintained spine database, the data was retrospectively analyzed. Overall, though a lack of imaging and follow-up data limits our analysis, this also highlights the difficulties of research and surgery in a low-resource setting, and we hope the scientific conclusions offered can improve the care of spinal trauma patients in Tanzania.

Conclusions

The current study summarizes the operative management of a large cohort of TSI patients that underwent surgical stabilization from a major referral hospital in East Africa. Four surgeries were offered: anterior cevical discectomy and fusion, anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest and plate, posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass screws, and posterolateral thoracic/lumbar fusion. The majority of constructs (86%) involved short-segment stabilization, and in nearly two-thirds of cases, the UIV/LIV included the injured level or a junctional level. While faster time from admission to surgery was associated with improved neurologic function, only 4% of patients underwent surgery within 3 days of admission. Lack of finances to pay for implants was the driving factor for limited construct size and delays to surgery, both reducing the quality of care delivered. Several important themes emerge, such as prioritizing early surgery, improving implant availability, ensuring rapid prehospital transfer, and capturing long-term follow-up.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Scott L. Zuckerman, MD, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2951-2942

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2951-2942

References

- 1. GBD 2016 Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:56–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar R, Lim J, Mekary RA, et al. Traumatic spinal injury: global epidemiology and worldwide volume. World Neurosurg. 2018;113:e345–e363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moshi H, Sundelin G, Sahlen KG, Sorlin A. Traumatic spinal cord injury in the north-east Tanzania—describing incidence, etiology and clinical outcomes retrospectively. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1355604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Obalum DC, Giwa SO, Adekoya-Cole TO, Enweluzo GO. Profile of spinal injuries in Lagos, Nigeria. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Divanoglou A, Westgren N, Seiger A, Hulting C, Levi R. Late mortality during the first year after acute traumatic spinal cord injury: a prospective, population-based study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lofvenmark I, Norrbrink C, Nilsson Wikmar L, Lofgren M. ‘The moment I leave my home—there will be massive challenges”: experiences of living with a spinal cord injury in Botswana. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1483–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lofvenmark I, Wikmar LN, Hasselberg M, Norrbrink C, Hultling C. Outcomes 2 years after traumatic spinal cord injury in Botswana: a follow-up study. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lofvenmark I, Hasselberg M, Nilsson Wikmar L, Hultling C, Norrbrink C. Outcomes after acute traumatic spinal cord injury in Botswana: from admission to discharge. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Budohoski KP, Ngerageza JG, Austard B, et al. Neurosurgery in East Africa: innovations. World Neurosurg. 2018;113:436–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leidinger A, Kim EE, Navarro-Ramirez R, et al. Spinal trauma in Tanzania: current management and outcomes [published online April 5, 2019]. J Neurosurg Spine. doi:10.3171/2018.12.SPINE18635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choi JH, Park PJ, Din V, Sam N, Iv V, Park KB. Epidemiology and clinical management of traumatic spine injuries at a major government hospital in Cambodia. Asian Spine J. 2017;11:908–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schnake KJ, Schroeder GD, Vaccaro AR, Oner C. AOSpine Classification Systems (subaxial, thoracolumbar). J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31(suppl 4):S14–S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yacoub AR, Joaquim AF, Ghizoni E, Tedeschi H, Patel AA. Evaluation of the safety and reliability of the newly-proposed AO spine injury classification system. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40:70–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirshblum SC, Waring W, Biering-Sorensen F, et al. Reference for the 2011 revision of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gelb DE, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, et al. Treatment of subaxial cervical spinal injuries. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(suppl 2):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderson PA, Raksin PB, Arnold PM, et al. Congress of Neurological Surgeons systematic review and evidence-based guidelines on the evaluation and treatment of patients with thoracolumbar spine trauma: surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2019;84:E56–E58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eichholz KM, Rabb CH, Anderson PA, et al. Congress of Neurological Surgeons systematic review and evidence-based guidelines on the evaluation and treatment of patients with thoracolumbar spine trauma: timing of surgical intervention. Neurosurgery. 2019;84:E53–E55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aleem IS, DeMarco D, Drew B, et al. The burden of spine fractures in India: a prospective multicenter study. Global Spine J. 2017;7:325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lalwani S, Singh V, Trikha V, et al. Mortality profile of patients with traumatic spinal injuries at a level I trauma care centre in India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:40–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nwankwo OE, Uche EO. Epidemiological and treatment profiles of spinal cord injury in southeast Nigeria. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mattiassich G, Gollwitzer M, Gaderer F, et al. Functional outcomes in individuals undergoing very early (<5 h) and early (5-24 h) surgical decompression in traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: analysis of neurological improvement from the Austrian Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:3362–3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim M, Hong SK, Jeon SR, Roh SW, Lee S. Early (≤48 hours) versus late (>48 hours) surgery in spinal cord injury: treatment outcomes and risk factors for spinal cord injury. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:e513–e525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dvorak MF, Noonan VK, Fallah N, et al. The influence of time from injury to surgery on motor recovery and length of hospital stay in acute traumatic spinal cord injury: an observational Canadian cohort study. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:645–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jug M, Kejzar N, Vesel M, et al. Neurological recovery after traumatic cervical spinal cord injury is superior if surgical decompression and instrumented fusion are performed within 8 hours versus 8 to 24 hours after injury: a single center experience. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1385–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fehlings MG, Vaccaro A, Wilson JR, et al. Early versus delayed decompression for traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: results of the Surgical Timing in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (STASCIS). PLoS One. 2012;7:e32037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fehlings MG, Rabin D, Sears W, Cadotte DW, Aarabi B. Current practice in the timing of surgical intervention in spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(21 suppl):S166–S173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lofvenmark I, Norrbrink C, Nilsson-Wikmar L, Hultling C, Chakandinakira S, Hasselberg M. Traumatic spinal cord injury in Botswana: characteristics, aetiology and mortality. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ametefe MK, Bankah PE, Yankey KP, Akoto H, Janney D, Dakurah TK. Spinal cord and spine trauma in a large teaching hospital in Ghana. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:1164–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]