Abstract

Background:

Frailty is highly prevalent among older adults, and associated with cognitive decline. Relationship between frailty and Motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR), a pre-dementia syndrome characterized by the presence of subjective cognitive complaints and slow gait, is yet to be elucidated.

Objective:

To examine whether frailty increases the risk of developing incident MCR.

Methods:

We analyzed 641 adults, aged 65 and above, participating in the LonGenity study. Frailty was defined using a 41-point cumulative deficit frailty index (FI). MCR was diagnosed at baseline and annual follow-up visits using established criteria. Cox proportional hazard models were used to study the association of baseline frailty with incident MCR, and reported as Hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) adjusted for age, sex and education.

Results:

At baseline, 70 participants (10·9%) had prevalent MCR. Of the remaining 571 non-MCR participants (mean age 75.0, 57.3% women), 70 developed incident MCR (median follow-up 2.6 years). Higher frailty scores at baseline were associated with an increased risk of incident MCR (Hazard ratio for each 0.01 increase in the frailty index: 1.07; 95% confidence intervals 1.03–1.11; p value = 0.0002). The result was unchanged even after excluding mobility related or chronic illnesses items from the frailty index as well as accounting for reverse causation, competing risk of death, baseline cognitive status, social vulnerability, and excluding participants with Mild Cognitive Impairment syndrome.

Conclusions:

Higher levels of frailty increase risk for developing MCR, and suggest shared mechanisms. This association merits further study to identify strategies to prevent cognitive decline.

Keywords: Dementia, cumulative frailty score, slow gait, Cognition

INTRODUCTION

The motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR) is a pre-dementia syndrome characterized by cognitive complaints and slow gait[1, 2]. The concept of MCR is based on extensive body of research that indicates that gait impairment is a very early clinical feature in the dementia process[3]. Individuals with MCR are at high risk for transitioning to dementia, both Alzheimer’s disease type dementia (AD)[2] and vascular dementia[1]. MCR has improved predictive validity for dementia compared to its individual components of cognitive complaints or slow gait, and even after accounting for clinical overlap with Mild Cognitive Impairment syndrome (MCI)[2]. Strengths of the MCR construct are that it does not require cognitive or laboratory tests and slow gait is defined objectively, independent of examiner dependent gait evaluations. Though gait dysfunction is multifactorial, slow gait predicts cognitive decline irrespective of underlying causes[4]. MCR pathogenesis is still being elucidated but its status is predicting dementia risk is robust[1, 2, 5].

Frailty is a multidimensional construct, associated with low physiologic reserves and increased vulnerability to adverse outcomes such as disability and death[6]. Frailty has also been noted to increase the risk of cognitive decline, Alzheimer pathology, and the expression of the neuropathology as dementia. For example, in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, age related deficits predicted dementia[7]. Both the frailty phenotype[8] (with which MCR overlaps in the criterion of slow gait) and the degree of frailty are associated with postmortem Alzheimer pathology in adults with and without antemortem dementia[9]. The degree of frailty, expressed as the degree of age-related deficit accumulation, may also moderate the relationship between Alzheimer neuropathology and AD dementia diagnosis[10]. In multivariable models that adjusted for age, sex and education, people with low levels of neuropathology who nevertheless met clinical criteria for Alzheimer disease dementia had significantly higher levels of frailty than those without dementia; in contrast, those who met neuropathological criteria for Alzheimer disease, but who did not meet dementia criteria had significantly lower levels of frailty than those who met both clinical and neuropathological criteria for Alzheimer disease[9]. Frailty has also been linked to risk of developing vascular dementia[11]; implicating vascular mechanisms in addition to neurodegenerative. An accompanying editorial suggested that a biopsychosocial model of frailty, in which social factors were also considered, would even better clarify these relationships[12].

Building on these observations, we hypothesized that frailty may increase the risk of developing MCR. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a prospective cohort study in community-residing Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) older adults. Establishing the role of frailty in developing MCR may provide new insights into preventive strategies for dementia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population:

The LonGenity study, established in 2007, recruited a cohort of AJ adults age 65 and older, who were either offspring of parents with exceptional longevity (OPEL), defined as having at least one parent who lived to age 95 and older, or offspring of parents with usual survival (OPUS), defined as having neither parent who survived to age 95. The goal of LonGenity is to identify genotypes associated with longevity and their association with successful aging. Study participants were systematically recruited using voter registration lists or through contacts at synagogues, community organizations and advertisements in Jewish newspapers in the New York City area. Potential participants were contacted by telephone to assess interest and eligibility. AJ adults age 65 and above were invited to our center for further evaluation. Exclusion criteria include the following: a score > 8 on the Blessed-Information-Memory-Concentration test or > 2 on the AD8 at the initial screening interview, severe visual impairment, and having a sibling in the study. Participants received medical history, clinical and cognitive evaluations at baseline and annual follow-up visits. All participants signed written informed consents for study assessment and genetic testing prior to enrollment. The Einstein institutional review board approved the study protocol.

MCR syndrome:

MCR syndrome was diagnosed based on established criteria[1, 2, 5] as the presence of subjective cognitive complaints and slow gait in older individuals without dementia or mobility disability. MCR builds on definitions of MCI; substituting impairment on cognitive tests criterion in MCI with the criterion of slow gait. Cognitive complaints were based on responses by participants to standardized questions about memory as a part of the Health Self-Assessment Questionnaire and from the Geriatric Depression Scale[5]. Gait speed was measured using an 8.5 meter long computerized walkway with embedded pressure sensors (GAITRite; CIR Systems, PA). The GAITRite system is widely used in clinical and research settings, and excellent reliability has been reported in our and other centers[13, 14]. Participants walked on the walkway at their normal pace in a quiet well-lit room wearing comfortable footwear and without any attached monitors. Slow gait was defined as walking speed one standard deviation (SD) or more below age and sex specific means as described in previous MCR studies in the LonGenity cohort[2, 5]. Dementia was diagnosed at consensus case conference after review of all available clinical, neuropsychological and medical information[15].

Frailty:

The two common clinical approaches to defining frailty are as a cumulative deficit index[16, 17] or a clinical syndrome[18]. We used the cumulative deficit frailty index (FI) as the predictor as commonly used syndromic frailty definitions have slow gait as a key criterion[18], which would lead to diagnostic circularity; using slow gait in both the predictor and outcome. The variables for the FI were selected using a standard procedure in which the criteria were:association with health status, biologically relevant, accumulates with age, should not saturate at an earlier age (e.g. presbyopia), and represent multiple organ systems[19]. A minimum of 30 variables is recommended for developing the FI[17], and has been shown to predict institutionalization, deteriorating health, and death[17]. We selected 41 variables to include in our FI based on this recommended approach[17]. Slow gait was not included in the FI as it is one of the main components of MCR. In case of binary variables, ‘0’ represents no deficit and ‘1’ represents a deficit. Continuous or rank variables were graded from 0 (no deficit) to 1 (maximum deficits). The variables and cut-off used for construction of FI are shown in Table 1. The FI was calculated by adding the number of deficits, and then dividing the total by total number of variables per participant; resulting in a range of scores from 0 (no frailty) to 1 (‘complete’ frailty) for each individual[17]. The distribution of FI was similar to that obtained in earlier studies[19] .

Table.1.

Health variables used for construction of cumulative frailty index

| Variable | Coding | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Help bathing | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 2 | Help dressing | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 3 | Help getting in/out of chair | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 4 | Help walking around house | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 5 | Help eating | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 6 | Help grooming | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 7 | Help using toilet | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 8 | Help up/down stairs | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 9 | Help lifting 10 lbs | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 10 | Help shopping | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 11 | Help with housework | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 12 | Help with meal preparations | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 13 | Help taking medication | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 14 | Help with finances | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 15 | Lost more than 10 lbs in last year | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 16 | Self rating of health | Poor = 1, Fair = 0.75, Good = 0.5, V. Good = 0.25, Excellent = 0 |

| 17 | How health has changed in last year | Worse = 1, Better/Same = 0 |

| 18 | Hospitalized/ER visits | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 19 | Cut down on usual activity (in last month) | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 20 | Walk outside | <3 days = 1, ≤ 3 days = 0 |

| 21 | Feel everything is an effort | Most of time = 1, Sometime = 0.5, Rarely = 0 |

| 22 | Feel depressed | Most of time = 1, Sometime = 0.5, Rarely = 0 |

| 23 | Feel happy | Most of time = 0, Sometime = 0.5, Rarely = 1 |

| 24 | Health interfered with social activities | Not at all - Slightly = 0, Moderately - Extremely = 1 |

| 25 | Have trouble getting going | Most of time = 1, Sometime = 0.5, Rarely = 0 |

| 26 | Moderate activity affected | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 27 | High blood pressure | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 28 | Heart attack | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 29 | CHF | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 30 | Stroke | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 31 | Cancer | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 32 | Diabetes | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 33 | Arthritis | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 34 | Chronic lung disease | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 35 | Cognitive test: Blessed | <2=0: 2-3=0.25: 4-7=0.50: >7 =1 |

| 36 | Peak flow | Men=<340 liters/min; Women=<310 liters/min |

| 37 | BMI | 1 if BMI <18.5 or >=30 |

| 38 | Grip strength | Men BMI=<24, GS=<29 :Men BMI 24.1-28, GS=<30:Men BMI>28, GS=<32: Women BMI=<23, GS=<17:Women BMI 23.1-26, GS=<17.3:Women BMI 26.1-29,GS=<18: Women BMI >29, GS=<21 |

| 39 | Falls | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 40 | Memory changes | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| 41 | History of Parkinson's disease | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

Statistical analysis:

Baseline characteristics of participants were compared using descriptive statistics (Table 3). Cox proportional hazard models were used to compute hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI to predict incident MCR syndrome based on baseline frailty status (Model:1). For ease of interpretation; the FI was multiplied by 100 (range 0-100), and risk for each 0.01 increase in the FI score reported. Time scale was follow-up time in years from baseline assessment to incident MCR diagnosis or final contact. Participants who developed incident dementia (n = 6) without an interim diagnosis of MCR at follow-up visits were not counted as incident MCR because there may be dementia pathways without an MCR stage. All models were adjusted for age, sex and education years. To graphically depict results using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, we created a categorical definition of frailty as a secondary predictor of incident MCR. This dichotomous frailty categorization was based on a validated cut-off score of 0.2 or more on the FI,[19] which is close to one SD over the mean FI value (mean 0.16, SD 0.08) for the overall LonGenity sample.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of LonGenity cohort at baseline by MCR status

| No MCR* (n=501) |

Incident MCR (n=70) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 75.03±6.34 | 75.05±6.52 |

| Women, n (%) | 291(58.1) | 34(48.6) |

| Education, mean y | 17.59±2.75 | 17.79±2.79 |

| Frailty index, Mean± SD | 0.15±0.07 | 0.17±0.08 |

| Social vulnerability index, Mean± SD | 0.10±0.09 | 0.12±0.11 |

| Medical illnesses | ||

| Global health score, mean ± SD** | 0.97±0.91 | 1.30±1.07 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 197(39.3) | 40(57.1)* |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 25(5.0) | 8(11.4) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 3(0.6) | 1(1.4) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 9(1.8) | 6(8.6)* |

| Cancer, n (%) | 173(34.5) | 24(34.3) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 36(7.2) | 9(12.9) |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 12(2.4) | 2(2.9) |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 200(40.0) | 25(35.7) |

| Parkinson, n (%) | 5(1.0) | 0(0) |

| Depression, n (%) | 96(19.2) | 16(22.9) |

| Cognitive tests | ||

| FCSRT free recall, mean (SD) | 33.80±5.22 | 33.27±4.80 |

| DSST, mean (SD) | 61.32±14.38 | 56.64±13.00 |

No MCR: participants who were free from MCR at baseline as well as throughout the study follow-up.

Significant difference in diseases prevalence at baseline when incident MCR participants were compared with non-MCR group.

Presence or absence of physician diagnosed depression, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, myocardial infarction, strokes, Parkinson's disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, and arthritis was used to calculate a global health score (range 0–9) as previously described.[4]

We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses; all adjusted for age, sex and education years. We recomputed the FI excluding four mobility-associated variables (Table 1) in addition to slow gait which was excluded in primary model: help walking around the house, difficulty climbing up or down stairs, difficulty walking outside, and falls (Model 2). To account for competing risk arising from death, we reran the analysis excluding participants who died during follow-up (Model 3). We used competing risk analysis to confirm our results. To account for overlap between physical and cognitive frailty, we adjusted the model for baseline Free recall from the Free and Cued selective reminding test[20] (memory) and Digit Symbol Substitution Test[21] (executive function) scores (Model 4). To account for overlap between MCR and MCI, we ran the model excluding prevalent MCI as well as participants who developed incident MCI on follow-up visits at or prior to the visit at which incident MCR was diagnosed (Model 5). To account for presence of frailty in individuals who missed meeting MCR criteria at baseline (reverse causation), we repeated the analysis excluding individuals who developed incident MCR in the first two years of follow-up (Model 6). A general measure of social vulnerability combining a variety of factors such as socioeconomic status, social supports and social engagement into a single measure can predict negative health outcomes including cognitive decline and mortality, especially in frail older adults[22, 23]. Social related variables that could be considered as deficits were identified (Table 2) to create a 18-point social vulnerability index using established approaches[22, 23], and included in our model (Model 7). To assess whether the association between frailty and MCR may be due to shared comorbidities, we recomputed the FI excluding nine physician diagnosed chronic illnesses reported by participants from the index (Model 8). We then adjusted this model for the nine individual chronic illnesses (diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, myocardial infarctions, strokes, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, chronic obstructive lung disease, and arthritis) in the model.

Table 2.

Variables used for construction of Social Vulnerability Index

| Sl.no | Variable | Coding |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Communication in English | First Language English (No=1; Yes=0) |

| 2 | Marital Status | What is your current marital status?(Married=0, Separated=1, Widowed=1, Never Married=1) |

| 3 | Live Alone | Currently live alone?( Yes=1; No=0) |

| 4 | Income | What is your current income? 1=<Poverty level (<$15000); 0= All others |

| 5 | Education | <12 years of education=1 |

| 6 | Assistance at home | Do you currently receive assistance at home? (Yes=1;, No=0) |

| 7 | Helplessness | Do you often feel helpless? (Yes=1;, No=0) |

| 8 | Hopelessness | Do you feel that your situation is hopeless? (Yes=1; No=0) |

| 9 | Telephone Use | Ability to use telephone Yes=0, No=1 |

| 10 | Mode of transportation: | Assistance from other=1: independent=0 |

| 11 | Get to places out of walking distance | Physical Ambulation :Assistance from other=1; independent=0 |

| 12 | Activities and Interests | Have you dropped may of your activities and interest? Yes=1, No=0 |

| 13 | Going out | Do you prefer to stay at home at night rather than go out and do new thing? (Yes=1;No=0) |

| 14 | Enjoying life | Wonderful to be alive now? (Yes=0 ;No=1) |

| 15 | Emptiness in Life | Do you feel that your life is empty? (yes=1; No=0) |

| 16 | Boredom | Do you get bored? (Yes=1; No=0) |

| 17 | Vulnerable | Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you? (Yes=1; No=0) |

| 18 | Satisfaction with life | Are you basically satisfied with life? (Yes=0; No=1) |

Proportional hazards assumptions of all models were tested graphically and analytically, and adequately met. All analyses were done with SPSS software (version 24; IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

Study population:

Of the 886 participants without dementia at baseline enrolled in the LonGenity study between October 2008 and January 2016, 641 completed gait and subjective cognitive complaint questionnaires. Of these 641 eligible participants, there were 70 prevalent cases of MCR and 571 participants were free from MCR at baseline. Demographic and clinical characteristics by MCR status are summarized in Table 3. Overall, the mean age was 75.09 years (SD 6.47), 56.90% of participants were female, and mean years of education was 17.64 (SD 2.77). Among the nine chronic illness, hypertension (p = 0.003) and stroke (p = 0.001) were significantly more prevalent in participants who developed MCR than those who remained MCR free (Table 3).

Incident MCR:

Over a median follow-up of 2.59 years (SD 2.09), 70 of the 571 initially MCR-free participants at baseline developed incident MCR. The median follow-up was similar in MCR (2.43 years, SD: 1.65) and non-MCR cases (2.63 years, SD: 2.15). The baseline FI score was 0.17 (SD 0.08) in incident MCR cases and 0.15 (SD 0.07) in non-MCR cases (Table 2). Baseline FI scores were associated with increased risk of developing MCR (HR per 0.01 increase on FI 1.07; 95% CI 1.03–1.11) (Model 1) (Table 4).

Table 4: Association of Frailty Index with incident MCR using Cox regression analysis.

All models below are adjusted for age, sex and education-years. Results are reported as Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI for each 0.01 Frailty Index increase.

| Model | Description | Events (MCR)/ Total participants |

HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adjusted for age, sex and education-years. | 68/551 | 1.07 | 1.03-1.11 | <0.001 |

| 2 | FI redefined excluding mobility related items. | 68/551 | 1.07 | 1.03-1.10 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Excluded participants who died before MCR. | 68/534 | 1.07 | 1.03-1.11 | <0.001 |

| 4 | Adjusted for cognitive scores. | 67/542 | 1.06 | 1.03-1.10 | 0.001 |

| 5 | MCI free model. | 57/514 | 1.06 | 1.02-1.10 | 0.004 |

| 6 | Excluded participants who developed incident MCR in the first two years of follow-up | 40/520 | 1.05 | 1.00-1.10 | 0.035 |

| 7 | Adjusted for social vulnerability index score. | 68/550 | 1.06 | 1.02-1.10 | 0.003 |

| 8 | FI redefined excluding chronic illness items. | 68/540 | 1.06 | 1.02-1.09 | 0.002 |

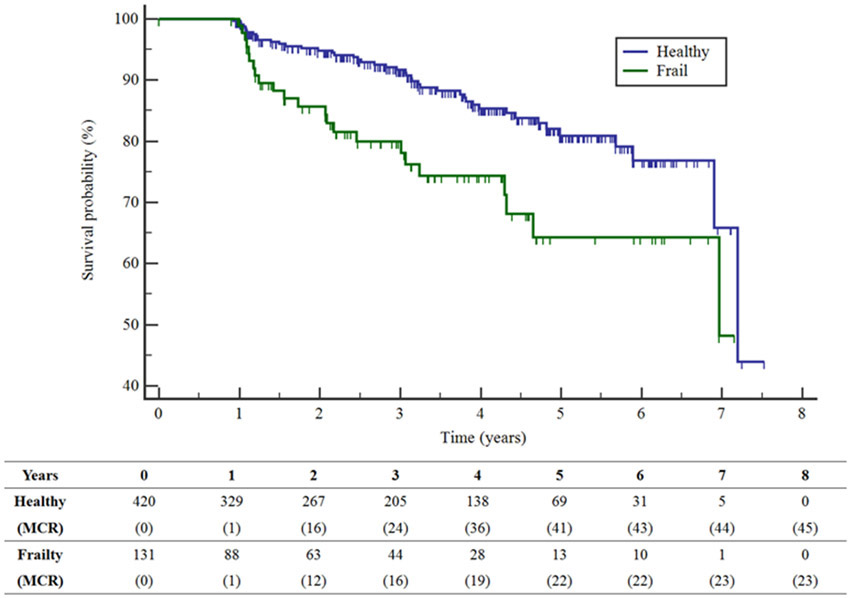

Figure 1 shows that the 131 participants with frailty (dichotomous definition) at baseline had significantly reduced time to developing incident MCR compared to the 420 participants without frailty at baseline (log rank test Chi-square=9.66, p=0.002). Twenty participants had missing data, and were not included in this analysis.

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier survival curves for time to MCR for participants who are healthy (blue) and frail (green).

Table shows number of participants at risk by frailty status and cumulative number of incident MCR cases (in parenthesis) at follow-up intervals in years.

Sensitivity analysis:

Table 4 summarizes the sensitivity analyses. Sample sizes varied from 517 to 551 due to missing data for specific models.

Model 2: The baseline modified FI score (excluding mobility related items) was 0.18 (SD 0.08) in incident MCR cases and 0.15 (SD 0.07) in non-MCR participants. The mobility free FI predicted incident MCR (HR 1.07).

Model 3: Baseline FI score predicted incident MCR even after accounting for death as a competing risk by excluding 17 cases who died over follow-up (HR 1.07). Cumulative incidence function estimates from competing risk data confirmed this association (data not shown).

Model 4: Additional adjustments for baseline memory and non-memory test scores in Model 1 did not materially change the association of FI with incident MCR (HR 1.06).

Model 5: After excluding 28 prevalent MCI cases and 9 participants who developed incident MCI before or on the same wave as incident MCR, FI remained a predictor of incident MCR (HR 1.06).

Model 6: To account for reverse causation, we excluded 31 participants who developed incident MCR in the first two years follow-up; FI predicted incident MCR in this model (HR 1.05).

Model 7: The mean social vulnerability scale score at baseline was 0.12 (SD 0.11) in incident MCR cases and 0.10 (SD 0.09) in non-MCR participants. The social vulnerability index predicted incident MCR (HR adjusted for age, sex and education 1.03, 95% CI 1.01-1.06). However, the social vulnerability index (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.99-1.04) was no longer significant when included in the model along with FI. FI still predicted incident MCR in this model (HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02-1.10).

Model 8: The FI score (excluding nine chronic illness items) at baseline was 0.17 (SD 0.08) in incident MCR cases and 0.15 (SD 0.08) in non-MCR participants. The modified FI without chronic illnesses items also predicted incident MCR (HR 1.06). When the nine chronic illnesses were added to the model, only hypertension (HR 1.80, 95% CI 1.05-3.09) and strokes (HR 6.44, 95% CI 2.08-20.01) predicted incident MCR. However, even in this model that adjusted for the nine chronic diseases, the modified FI excluding chronic illness items still predicted incident MCR (HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01-1.09).

DISCUSSION

We report an association between frailty, defined using a cumulative deficit score[19], and incidence of MCR in a community residing cohort of 571 well characterized AJ older adults. We showed that higher levels of frailty predicted the incidence of MCR; even after accounting for potential confounders and considering alternate explanations. Given the continuous nature of the Frailty Index used in our study, concurrence is likely with participants meeting MCR criteria at some point in the spectrum of frailty. The association observed between frailty and MCR also suggests possible shared etiologies, likely related to the many molecular and cellular features that constitute ageing.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to link frailty to MCR. Hence, previous comparisons are not available. However, we showed that individual variables linked to frailty such as obesity and sedentariness predicted risk of incident MCR in LonGenity and other cohorts[5]. Frailty has been reported to increase risk of other pre-dementia syndromes such as MCI[24, 25]. Physical frailty at baseline measured using a composite measure of four components (grip strength, timed walk, body composition, and fatigue) predicted incident MCI in over 700 participants without cognitive impairment recruited from retirement communities in Chicago[24]. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging reported that frailty measured using a cumulative deficit index predicted incident MCI in initially cognitively normal older adults[25]. A frailty index was associated with an increased risk of developing incident mild neurocognitive disorder and dementia in 1,575 community-living Chinese older adults in Singapore[26].

Frailty and MCR may be linked by multiple biological pathways that commonly are disordered in ageing. Inflammation, oxidative stress and endocrine pathways play important roles in the pathogenesis of frailty[27]. We reported that gene variants in the regulatory region of IL10 gene were associated with incident MCR in our cohort[28]. Furthermore, higher levels of inflammation increase risk for MCR components such as slow gait and cognition[29, 30].Genome wide association studies showed an overlapping hotspot (9p21-23 locus) with multiple complex disorders, and frailty was associated with this locus in the LonGenity cohort[31]. Obesity predicted incident MCR in our multi-center study[2]. We reported that obesity related genetic traits predicted MCR in participants with European ancestry in the Health and Retirement study[32].

Higher comorbidity (global health score[4]) was seen at baseline in incident MCR cases. In our analyses, we accounted for comorbidity by removing chronic illness items from FI as well as adjusting for individual diseases; frailty still predicted MCR in these analyses. Among the individual illnesses, hypertension and strokes predicted incident MCR. Strokes predicted MCR in our pooled analyses in four US based cohorts including LonGenity [5]. However, in our sensitivity anlysis, adjusting for hypertension and strokes in Model 8 did not take away the association of the modified FI with incident MCR; indicating involvement of other non-vascular pathways in the pathogenesis of MCR.

Frailty encompasses physical, cognitive, and psychosocial dimensions[12]. Presence and quality of social relationships have been linked to risk of developing dementia. In the present study, we observed an association of social vulnerability index with MCR that was no longer significant when frailty was accounted in the model; raising the possibility that social vulnerability may act via promoting risk of frailty through multiple mechanisms including factors related to socioeconomic status, education, access to health services, and lack of social support[22, 23]. Neuropsychaitric symptoms such as depression and loneliness are linked to biological pathways related to dementias, and could be examined in the context of frailty and MCR in future studies[33, 34].

The strengths of this study include the systematic cognitive and clinical assessments as well as use of a composite cumulative deficit frailty index. The FI may better capture the multidimensionality of frailty compared to syndromic frailty definitions. Having been involved in developing the MCR concept[1, 2, 5], we were careful to be consistent in defining MCR. Our sensitivity analyses accounted for multiple confounders and alternate explanations such as competing risks of death, overlap with MCI, social vulnerabilities and reverse causation; lending confidence to our findings. Frailty predicted MCR even after excluding prevalent and incident MCI cases as well as accounting for baseline cognitive status, suggesting that frailty might increase dementia risk through pathways independent from MCI. Misclassification of MCR cases as normal at baseline might result in spurious associations of frailty with MCR; however, excluding individuals who converted to MCR over the first two years of follow-up did not change the observed findings.

Limitations include the nature of the study population, which was racially homogenous (as LonGenity was set up as a genetic discovery study) and highly educated. Cognitive frailty has been proposed as a concept to capture combined cognitive and motor impairments early in the course of dementia; however, operational definitions of cognitive frailty can effect the prevalence of this concept and predictive validity for dementia [35]. For instance, the definition of cognitive frailty proposed by the IANA/IAGG working group includes both physical (presence of physical frailty) and cognitive (Clinical Dementia Rating scale score of 0.5) impairments. MCR could also be considered as an alternate definition of cognitive frailty as it includes both physical and cognitive criteria. The physical and cognitive impairments required to meet the IAGG/IANA cognitive frailty definition are more severe than those used to operationalize MCR, resulting in the former likely capturing individuals at later stages of cognitive decline [35]. Our findings suggest that the link between frailty (quantitative estimate of aging risk) and disease expression in late-life neurodegeneration is likely to be robust. Even so, our findings need to be replicated in other populations and settings.

Our findings support a role for frailty in the pathogenesis of MCR; underlying biological mechanisms need to be elucidated as a prelude to developing preventive interventions to reduce risk of cognitive decline in aging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS :

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (1R56AG057548-01). The LonGenity study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01AG044829, P01AG021654, R01 AG 046949, K23AG051148, P30AG038072, Paul Glenn Foundation Grant and American Federation for Aging Research.

Footnotes

Conflcit of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- [1].Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R (2012) Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and the risk of dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68, 412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Verghese J, Annweiler C, Ayers E, Barzilai N, Beauchet O, Bennett DA, Bridenbaugh SA, Buchman AS, Callisaya ML, Camicioli R (2014) Motoric cognitive risk syndrome Multicountry prevalence and dementia risk. Neurology 83, 718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kueper JK, Speechley M, Lingum NR, Montero-Odasso M (2017) Motor function and incident dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and ageing 46, 729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R, Xue X (2007) Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78, 929–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Verghese J, Ayers E, Barzilai N, Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Holtzer R, Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Wang C (2014) Motoric cognitive risk syndrome Multicenter incidence study. Neurology 83, 2278–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K (2013) Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381, 752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K (2014) Age-related deficit accumulation and the risk of late-life dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 6, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Buchman AS, Schneider JA, Leurgans S, Bennett DA (2008) Physical frailty in older persons is associated with Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology 71, 499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wallace LM, Theou O, Godin J, Andrew MK, Bennett DA, Rockwood K (2019) Investigation of frailty as a moderator of the relationship between neuropathology and dementia in Alzheimer's disease: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Lancet Neurol 18, 177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wallace L, Theou O, Rockwood K, Andrew MK (2018) Relationship between frailty and Alzheimer's disease biomarkers: A scoping review. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 10, 394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Solfrizzi V, Scafato E, Frisardi V, Seripa D, Logroscino G, Maggi S, Imbimbo BP, Galluzzo L, Baldereschi M, Gandin C (2013) Frailty syndrome and the risk of vascular dementia: the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Alzheimer's & Dementia 9, 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Panza F, Lozupone M, Logroscino G (2019) Understanding frailty to predict and prevent dementia. Lancet Neurol 18, 133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Holtzer R, Wang C, Verghese J (2012) The relationship between attention and gait in aging: facts and fallacies. Motor control 16, 64–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Brach JS, Perera S, Studenski S, Newman AB (2008) The reliability and validity of measures of gait variability in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89, 2293–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Kuslansky G, Sliwinski MJ, Stewart WF, Verghese J, Crystal HA, Buschke H (2003) Screening for Dementia by Telephone Using the Memory Impairment Screen. J Am Geriatr Soc 51, 1382–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K (2001) Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal 1, 323–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rockwood K, Mitnitski A (2007) Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62, 722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G (2004) Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K (2008) A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 8, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Grober E, Buschke H, Crystal H, Bang S, Dresner R (1988) Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology 38, 900–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wechsler D (1955) Manual for the Wechsler adult intelligence scale. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Armstrong JJ, Mitnitski A, Andrew MK, Launer LJ, White LR, Rockwood K (2015) Cumulative impact of health deficits, social vulnerabilities, and protective factors on cognitive dynamics in late life: a multistate modeling approach. Alzheimers Res Ther 7, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Andrew MK, Mitnitski AB, Rockwood K (2008) Social vulnerability, frailty and mortality in elderly people. PloS one 3, e2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA (2010) Physical frailty is associated with incident mild cognitive impairment in community-based older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 58, 248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bartley MM, Christianson TJ, Pankratz V, Roberts RO, Geda YE, Petersen RC (2014) Frailty and the risk of incident mild cognitive impairment: The mayo clinic study of aging. Alzheimers Dement 10, P267. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, Gao Q, Feng L, Lee TS, Tsoi T, Chong MS, Lim WS, Collinson S, Yap P (2017) Physical frailty, cognitive impairment, and the risk of neurocognitive disorder in the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 72, 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Walston JD (2005) Biological markers and the molecular biology of frailty In Longevity and frailty Springer, pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sathyan S, Barzilai N, Atzmon G, Milman S, Ayers E, Verghese J (2017) Association of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 polymorphisms with motoric cognitive risk syndrome in an Ashkenazi Jewish population. Neurobiol Aging 58, 238. e231–238. e238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Verghese J, Holtzer R, Oh-Park M, Derby CA, Lipton RB, Wang C (2011) Inflammatory markers and gait speed decline in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66, 1083–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yaffe K, Kanaya A, Lindquist K, Simonsick EM, Harris T, Shorr RI, Tylavsky FA, Newman AB (2004) The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline. Jama 292, 2237–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sathyan S, Barzilai N, Atzmon G, Milman S, Ayers E, Verghese J (2018) Genetic insights into frailty: Association of 9p21-23 locus with frailty. Front Med (Lausanne) 5, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sathyan S, Wang T, Ayers E, Verghese J (2019) Genetic basis of motoric cognitive risk syndrome in the Health and Retirement Study. Neurology 92, e1427–e1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lozupone M, Panza F, Piccininni M, Copetti M, Sardone R, Imbimbo BP, Stella E, D’Urso F, Rosaria Barulli M, Battista P (2018) Social dysfunction in older age and relationships with cognition, depression, and apathy: the GreatAGE study. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Donovan NJ, Okereke OI, Vannini P, Amariglio RE, Rentz DM, Marshall GA, Johnson KA, Sperling RA (2016) Association of higher cortical amyloid burden with loneliness in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA psychiatry 73, 1230–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, Van Kan GA, Ousset P-J, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Ritz P, Duveau F, Soto M, Provencher V (2013) Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (IANA/IAGG) international consensus group. The journal of nutrition, health & aging 17, 726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]