Abstract

As the United States population ages, a higher share of adults is likely to use long-term services and supports. This change increases physicians’ need for information about assisted living and residential care (AL/RC) settings, which provide supportive care and housing to older adults. Unlike skilled nursing facilities, states regulate AL/RC settings through varying licensure requirements enforced by state agencies, resulting in differences in the availability of medical and nursing services. Where some settings provide limited skilled nursing care, in others, residents rely on resident care coordinators, or their own physicians to oversee chronic conditions, medications, and treatments. The following narrative review describes key processes of care where physicians may interact with AL/RC operators, staff, and residents, including care planning, managing Alzheimer’s disease and related conditions, medication management, and end-of-life planning. Communication and collaboration between physicians and AL/RC operators are a crucial component of care management.

Keywords: assisted living, residential care, long-term services and supports, primary care physicians

Introduction

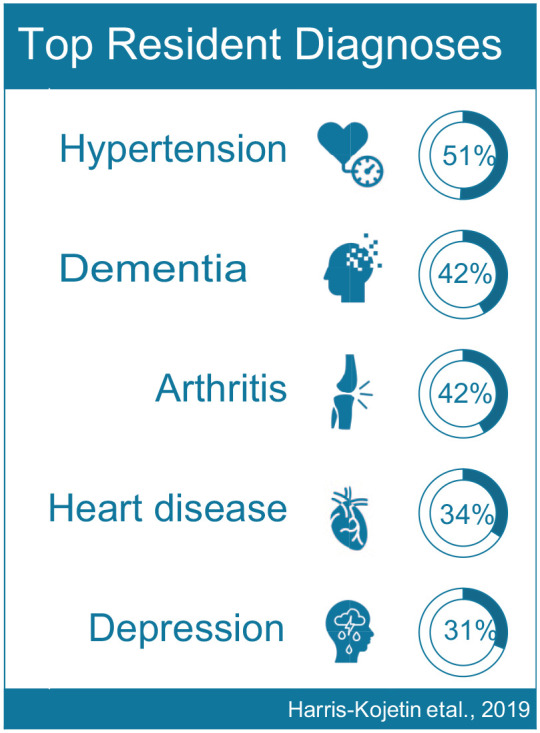

Demand for geriatric clinical practitioners and long-term care services will accompany increases in the older adult (65+) population (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020; Thach & Wiener, 2018). System changes, including a recent national shift toward interdisciplinary primary care teams (American Hospital Association, 2013; Engel et al., 2016; Young et al., 2011) and community-based care expansion (e.g., assisted living) rather than skilled nursing facilities (SNF) has implications for older adults’ care management (Cornell et al., 2020; Silver et al., 2018). Nationally, 29,000 assisted living and residential care (AL/RC) settings licensed for four or more adults serve over 800,000 residents, compared to 15,600 SNFs that serve 1.3 million residents. AL/RC residents have significant health and personal care needs as described in Figures 1 and 2 (Khatutsky et al., 2016; Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of AL/RC resident support needs.

Note. Data from National Study of Long Term Care Providers (NSLTCP) and National Study of Residential Care Facilities (NSRCF).

Figure 2.

Most prevalent chronic health conditions among AL/RC residents.

Note. Data from NSLTCP.

Physicians serve an essential role as part of the healthcare team providing clinical oversight and care to AL/RC residents. Physician roles in AL/RC may include clinical services consultant, interprofessional care team member, medical director, geriatric care manager (Stall, 2009; Stone, 2006). States’ AL/RC regulations vaguely specify physicians’ involvement in AL/RC residents’ care processes (e.g., resident evaluations upon move-in and for retention, medication administration and review, hospice orders) (National Center for Assisted Living [NCAL], 2019).

There is a significant need for physicians to understand the contexts where their patients live, especially given the coronavirus pandemic, which disproportionately affects older adults in congregate care settings (Dosa et al., 2020). Though they provide housing and health services to older adults, AL/RC settings have largely been left out of the coronavirus conversation (Zimmerman et al., 2020). A combination of third-party services, direct care staff, and family caregivers provide care and social support are now limited by precautions to mitigate the spread of coronavirus (Dobbs et al., 2020; Young & Fick, 2020). Social isolation, loneliness, delirium, dementia management, medication administration, and effects of the coronavirus pandemic on caregivers of residents all intersect with the overall health and wellbeing of AL/RC residents (Brooke & Jackson, 2020; Brown et al., 2020; O’Hanlon & Inouye, 2020). Infection control requirements in AL/RC might not be as robust as in other care settings; 31 states have AL/RC regulations for infection control (Bucy et al, 2020).

There are four main reasons to highlight physicians’ roles in AL/RC settings. First, 16% of adults over 65 and 40% of adults over 85 need long-term health-related support due to significant cognitive and physical impairments (Johnson, 2017). Second, there are not enough clinicians with geriatric training to meet this demand (Warshaw & Bragg, 2016). Third, older adults and their families often seek physician advice regarding physical or cognitive decline, and care transitions (Hamdy, 2015; Holt, 2017; Oh & Rabins, 2019; Sedhom & Barile, 2017). Lastly, there is a lack of consensus on physicians’ roles related to clinical oversight given the interdisciplinary nature of healthcare teams in AL/RC (Katz et al., 2018; Resnick et al., 2018).

Methods

We used a narrative review to identify key topics of research and themes in physicians’ roles in AL/RC (Grant & Booth, 2009; Green et al., 2006). We limited this review to studies published after 2003, when a comprehensive report including recommendations regarding physicians’ roles in medication management and service plan development, among others, was presented to the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging (Assisted Living Workgroup, 2003). In fall 2019, we queried Google Scholar using the boolean search: allintitle: physician OR physicians OR physician’s AND “assisted living” OR “residential care.” This approach returned 20 publications, of which 14 were peer-reviewed journal articles; we reviewed these for relevance, identifying seven papers that directly address physician roles and perspectives on care delivery in AL/RC in the U.S. (Katz et al., 2018; Nyrop et al., 2011, 2012; Resnick et al., 2018; Schumacher et al., 2005; Schumacher, 2006; Sloane et al., 2011).

Physician Roles in Assisted Living/Residential Care Settings

The identified studies highlighted topics of communication, perceptions of staff, care delivery, and assessment. According to one study, physicians trust AL/RC staff less than SNF staff, raising concerns regarding AL/RC staff reliability when taking orders over the phone (Schumacher et al., 2005). Others observed disagreement between physicians and AL/RC staff over treatment plans and physician frustrations regarding unexplained additional paperwork, including multiple faxes and signed orders (Schumacher et al., 2005; Schumacher, 2006; Sloane et al., 2011). Two studies suggest miscommunication with AL/RC staff regarding responsibility for residents’ fall risk assessments (Nyrop et al., 2011, 2012). Based on these studies, literature cited in these studies, and states’ AL/RC regulatory summaries (Carder et al., 2015; National Center for Assisted Living [NCAL], 2019), we discuss topics summarized in Table 1 as relevant for physicians with patients living in AL/RC settings.

Table 1.

Key Points and Recommendations for Physicians with Patients in AL/RC.

| AL/RC settings |

| State regulatory approaches are unique; states may have more than one AL/RC type Learn about AL/RC in your state, and bordering states, if relevant Reliance on paraprofessional staff, nurse availability varies Physicians are care convoy members |

| Care planning and communication |

| Evaluation/assessment informs the care plan Develop communication plans with AL/RC staff Identify residents’ preferences and key staff contacts |

| Care transitions |

| Move-in and move-out may require physician input Use communication plans to track care transitions/changes in condition Consider telemedicine options to facilitate in-place assessment and care |

| People living with dementia |

| Recognize dementia versus delirium Identify underlying causes of behavioral expressions Prioritize nonpharmacologic strategies Know psychotropic medication risks |

| Medication management |

| Frequently review medications and treatment orders Consider: Potential drug-induced delirium Untreated pain Unrecognized sleep disorders Anticholinergic effects Use clear, specific language in medication and treatment parameters |

| End-of-life care |

| Third-party services including hospice may require physician orders Discuss advance care planning with patients and families |

AL/RC Settings, Their Residents, and Staff

In the U.S., AL/RC settings vary due to different state regulations, development and finance models, consumer demands, and resident makeup (Armstrong et al., 2016; Carder et al., 2015; Cornell et al., in press; Grabowski et al., 2012; Trinkoff, 2020). Proponents of AL/RC settings promote the social model of care and home-like environment that supports resident choice through community operations (Brown Wilson, 2007; Carder, 2002; Carder & Hernandez, 2004; Kane & Wilson, 1993). Providers must balance these person-centered values with operations, regulatory oversight, and health care provider goals of safety and beneficence (Calkins & Brush, 2016; Kapp, 1997; Morgan, 2009; O’Dwyer, 2013).

Each state regulates AL/RC differently, using state-specific terminology (e.g., assisted living facility, residential care facility, community residence, personal care home, dementia care units) to license operators (Carder et al., 2015). Nationally, the average capacity of AL/RC settings is 35 beds, ranging from small homes, with a capacity for fewer than ten residents, to apartment buildings housing hundreds (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019). Additionally, 23% of AL/RC settings offer dementia care units with 40 states regulating a special license or certification for dementia care (Cornell et al., in press; Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019). In the U.S, one in five AL/RC settings reported policies allowing for admission of residents needing ongoing skilled nursing services (20%), four out of five allowed for residents with needs including assistance with incontinence (82%), daily monitoring of blood sugar levels or insulin (81%), half allowed residents with assistance with cognitive impairment (55%), and one-third allowed residents in need of two-person or Hoyer lift transfer (33%) (Han et al., 2017).

Staff mix within AL/RC settings can include registered nurses (RNs), licensed professional/vocational nurses (LPN/LVNs), certified nursing assistants (CNAs), certified medication aides (CMAs), unlicensed direct care workers, and administrators. Thirty-eight states require RNs or LPN/LVNs to provide or supervise care (Beeber et al., 2018; Rome et al., 2019). Administrators are responsible for all AL/RC operations, such as staffing, resident care provision, and regulatory compliance. Compared to SNFs, fewer states require AL/RC administrator licensure (Carder et al., 2015; Dys et al., 2020; National Center for Assisted Living NCAL, 2019). The majority of the workforce in AL/RC settings are paraprofessionals. In comparison to SNFs, a larger proportion of these staff identify as men and have completed college (Kelly et al., 2020). They provide an average of 2.27 care hours per resident per day compared to licensed and registered nurses 0.2 hours (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019). Sixteen state agencies require minimum staffing ratios, while most states specify “sufficient” staff be present to address residents’ needs (Carder et al., 2016). Currently, there is no standard measure of “sufficient” staffing (Zimmerman et al., 2016).

Care Planning and Communication Among Physicians, Families, Residents, and Staff

AL/RC settings develop care plans for each resident. An admission assessment can inform the care plan, as can communication between the AL/RC setting and the resident’s physician after a change in condition. Care plans can promote role clarity among the care team by emphasizing participatory decision making and care coordination (Burt et al., 2014). Care plan requirements vary from state to state, but generally, they describe resident needs and preferences and corresponding health and social services (Unwin et al., 2019). Residences may require a physician to conduct the pre-admission assessment which can include medication review and clinical assessment for fall risk, physical and cognitive decline, and behavioral symptoms (National Center for Assisted Living [NCAL], 2019).

Unless an AL/RC setting employs or contracts a healthcare professional, individual residents’ physicians provide oversight and input on medical care provided offsite and onsite. Examples of the former include visits to specialists and admission to hospitals or acute care rehabilitation centers. Physicians also prescribe treatments delivered by AL/RC staff (e.g., medications), and third-party providers (e.g., hospice and home health care services). Interprofessional collaboration in care provision within AL/RC settings varies. A South Carolina-based study found administrators of freestanding AL/RCs were less likely than those co-located with a memory care unit to use a multidisciplinary team approach (Kelsey et al., 2010).

Research suggests physician offices may benefit from established communication procedures and parameters for AL/RC patient treatment. Examples include identifying a consistent person in the physician office to receive and triage messages from AL/RC staff, co-creating a protocol with the AL/RC setting or family members regarding necessary information for residents’ records, and developing specific medication parameters for paraprofessional staff to implement (Burt et al., 2014; Tjia et al., 2009; Winn et al., 2004). States post information for consumers about requirements for AL/RC scope of practice, staffing, and health services that can be used by physician offices to clarify responsibilities.

As of 2016, one-quarter of AL/RC settings (26%) reported using electronic health records (EHR) compared to 79% of physicians (Caffrey et al., 2020; Rao et al., 2019). Settings using EHRs reported greater health information exchange with physicians and pharmacies compared to their non-EHR counterparts (Caffrey et al., 2020). One Florida-based study found AL settings primarily used EHR for tracking resident demographics and medication lists (Holup et al., 2014). AL/RC EHR use may be less familiar to physicians who are accustomed to an integrated EHR for clinical decision making and information sharing with other providers (Munchhof et al., 2020; Rao et al, 2019).

In the AL/RC context, physicians are one member of an interdisciplinary care network, or “convoy,” comprising family, friends, AL/RC staff, therapists, and pharmacists (Kemp et al., 2018, 2019). Families provide a source of socioemotional support and financial and medical oversight for AL/RC residents (Gaugler & Kane, 2007). Families report wanting improved communication regarding healthcare needs, including whether to send their relatives to the emergency department or complete advance directives (Sharpp & Young, 2015).

Transport to medical appointments can be a challenge for residents, who rely on family, caregivers, or formal transportation services (Eby et al., 2017; Wolf & Jenkins, 2014). Telemedicine consults with AL/RC operators, care teams, or virtual appointments may be useful, especially in patients living with dementia, cognitive impairment, and mobility limitations (Daniel et al., 2015). Teleconferencing may also benefit physicians via consults with geriatric, older adult behavioral health, or dementia care specialists (Bennett et al., 2018; Catic et al., 2014; Oh & Rabins, 2019; Tso et al., 2016).

Resident Transitions Into, During, and From AL/RC Care

Cognitive decline and dementia progression can lead to numerous care transitions, which are associated with declines in health and quality of life for people living with dementia (PLWD) and their caregivers (Chyr et al., 2020; Ryman et al., 2018). Older adults and their families may seek advice from their physicians as they decide whether to move into an AL/RC (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020; Chen et al., 2008; Reinardy & Kane, 2003). One study reported significant caregiver distress at the lack of information or engagement from physicians in anticipating future needs and transitions for their loved ones with dementia (Liken, 2001).

Although AL/RC residents typically want to age in place, a move-out might become necessary if their care needs exceed the level of care the residence is licensed to provide (Ball et al., 2004; Chapin & Dobbs-Kepper, 2001; Munroe & Guihan, 2005). Residents may transfer to a dementia care unit co-located on the same property, offsite, a SNF, or another care setting (Shippee, 2009). Other transitions during residents’ tenure in AL/RC may include hospitalizations or treatment in acute care rehabilitation centers (Berish et al., 2018). A qualitative study of AL/RC and SNF residents and their families found that few received information about reasons for hospital admissions, had limited contact with physicians during hospitalization, and expressed uncertainty about treatments and discharge planning (Toles et al., 2012). Standardized communication and care planning, interprofessional cooperation, and person-centered, dementia-competent care can mitigate the negative effects of these potential transitions (Hirschman & Hodgson, 2018). Older adults’ engagement in decisions to move into AL/RC and transition or discharge during their stay is unclear (Chen et al., 2008; Mead et al., 2005; Shippee, 2009). Evidence-informed practice promotes involving both families and residents using clear, direct communication at every stage of care transition regardless of the destination (Jackson et al., 2016).

Managing Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders (ADRD)

AL/RC settings increasingly provide care to PLWD. Dementia-specific settings typically have controlled egress to prevent residents from exiting the building (except in emergency), dementia-specific staff training, increased staffing levels, or additional cognitive assessments, though specific requirements vary by state (Carder et al., 2016). Physicians play an important role in dementia diagnosis and management (Hamdy, 2015). The prevalence of residents with an ADRD diagnosis in AL/RC varies by state from 24% in Minnesota to 47% in North Carolina (Thomas, Belanger, et al., 2020). Dementia is associated with behavioral expressions, such as agitation, anxiety, depression, delusions, irritability, and sleeplessness (Ismail et al., 2016; Lyketsos, 2007; Roth & Brunton, 2019). One multistate study reported one-third of AL/RC residents expressed one or more behaviors (e.g., physical/verbal aggression, wandering, resistance to care) at least once a week (Gruber-Baldini et al., 2004). However, nearly all PLWD experience behavioral expressions (Lyketsos et al., 2002; Zimmerman et al., 2014).

Treatment decisions should be driven by the multiple possible causes of residents’ behavioral expressions (Lanctôt et al., 2017). When residents express behaviors, they may be communicating some unmet need (e.g., hunger, pain, or using the bathroom) (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2015; Gaugler et al., 2005; Smith & Buckwalter, 2005). Insomnia, especially common among older adults with cognitive impairment, may also result in preventable agitation or stress that manifests as behaviors (Hamdy et al., 2018). PLWD may experience delirium, often characterized by acute changes in focus or attention, hallucinations, and disruption to sleep-wake cycles as opposed to gradual cognitive decline (Morandi et al., 2017). If clinically managing a resident with behavioral expressions, physicians can reinforce treatment plans that emphasize identifying underlying causes. For example, the Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (ABC), Needs-Driven Dementia Compromised Behavior (NDB), and Describe, Investigate, Create, Evaluate (DICE) models frame identification of preceding and underlying factors that result in behaviors and provide guidance on person-centered interventions (Algase et al., 1996; Kales et al., 2014; Volicer & Hurley, 2003).

Medication Management

Assistance with medication administration is a major driver of older adult AL/RC admissions (Lieto & Schmidt, 2005). Healthcare professionals prescribe medications to AL/RC residents and may be informed by resident and family preferences and staff requests (Kerns et al., 2018; Look & Stone, 2018; Wolff & Spillman, 2014). Potentially harmful drug classes for older adults include analgesics, anticoagulants, antidepressants, antihypertensives, and antipsychotics due to increased risks of drug interactions, anticholinergic effects, falls, and early mortality (Fick et al., 2019; Ruscin & Linnebur, 2018). With limited clinical staff, physicians may serve as a resource for AL/RC residents and staff for medication-related questions and concerns.

Medication management in AL/RC settings involves direct care staff, nurses, pharmacists, and prescribers (Stefanacci & Haimowitz, 2012; Young et al., 2013). Residents capable of self-administration, as assessed by a physician, may do so in most settings (Carder & O’Keeffe, 2016). Many states permit trained, unlicensed staff to administer medications (Carder & O’Keeffe, 2016; Reinhard et al., 2006; Sikma et al., 2014). AL/RC credentialed and paraprofessional staff implement physicians’ orders for prescribed medications and treatments. The implications of this arrangement on resident care quality have not yet been studied.

Nonpharmacologic practices (e.g., psychosocial and environmental interventions) are considered the first line of therapy to manage behavioral expressions in AL/RC residents, though medication may be considered if they prove ineffective (Brodaty & Arasaratnam, 2012; Scales et al., 2018). When changing a resident’s medications, physicians should consider potential drug-induced delirium, untreated pain, unrecognized sleep disorders, risk/benefit analysis, and commit to ongoing medication review (Gill et al., 2019; Kales et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2018). Medication interactions can induce changes to residents’ affect, behavioral expressions, or physical conditions, raising the importance of communication and review of medication changes with AL/RC staff (Gurwitz et al, 2018; Mitty, 2009).

Over two-thirds (68%) of AL/RC settings report having a physician or pharmacist review residents’ medications for appropriateness (Dwyer et al., 2014). Physicians might collaborate with pharmacists or RNs to evaluate the risks and benefits of stopping, starting, or continuing medications during medication reviews of residents in their care (Hohmeier et al., 2019; Martin, 2007). Further, connecting with the AL/RC setting’s consultant pharmacist or nurses may be beneficial, as they are often responsible for regular (e.g., quarterly) medication review (Coulson & Blaszczyk, 2016; Rhoads & Thai, 2003). Managing medications, especially those following transitions in care, can be challenging as medication orders might change and multiple prescribers can be involved (Chhabra et al., 2012; Fitzgibbon et al., 2013). Staff who work with AL/RC residents daily may provide physicians with additional information regarding additional orders from specialists or concerns regarding regulatory compliance given current orders, another reason for clear communication, follow-up, and ongoing medication review.

End-of-Life (EoL) Care

Over half of AL/RC residents (57%) reside in the setting at end-of-life (EoL) (Thomas, Zhang, et al., 2020). EoL care for AL/RC populations is accompanied by unique challenges due to the presence of other residents, who have cognitive impairment as well as staff with varying training and experience with EoL care (Zimmerman et al., 2015). Palliative AL/RC services orient toward management of chronic conditions as most AL/RC resident deaths are attributed to gradual decline (Ball et al., 2014). Physicians may be involved in their patients’ EoL services, including managing changing medical care needs and coordinating with AL/RC staff and third-party agencies.

AL/RC settings in most states allow residents to receive third-party care including home health or hospice services while residing in the AL/RC setting. In a nationally representative sample, AL/RC residents’ average days spent on hospice in the last month of life ranged from two to fourteen days, depending on the state (Thomas, Zhang et al., 2020). In comparison to older adults living at home, hospice users in AL/RC settings are more likely to have dementia, enroll in hospice services closer to death, and less likely to receive opioids or die in an acute-care setting (Dougherty et al., 2015). Relationships between third-party service providers and AL/RC operators may or may not exist, complicating resident care coordination (Carder & Hernandez, 2004; Hernandez, 2005; Zimmerman & Sloane, 2007). AL/RC administrators value hospice teams that understand and respect the AL/RC staff by coordinating with AL/RC settings (Dobbs et al., 2006). Additionally, preliminary evidence suggests that when AL/RC staff are educated on EoL services, hospice utilization increases (Dobbs et al., 2018). When compared to SNF, AL/RC provided less pain management at EoL, possibly because these settings typically lack a licensed nurse to coordinate prescriptions with physicians (Dobbs et al., 2006).

Families of AL/RC residents’ have expressed concerns about communication between care providers and physicians, inadequate monitoring, and lack of staff knowledge regarding symptom management at EoL (Biola et al., 2007). Introducing the topic of advance care planning may encourage AL/RC residents and their families to discuss advance directives and preferences for their EoL experience. Residents’ physicians are expected to oversee medical care, even after residents begin hospice (Weckmann, 2008). Though challenging, physicians can initiate conversations with residents and families in collaboration with AL/RC staff regarding advance care planning, including physicians orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST), resident preferences, and advance directives (Beck et al., 2015; Dixon et al., 2002; Greenstein et al., 2019; Hickman et al., 2010).

Conclusion

This narrative review describes roles physicians may play in the AL/RC context. Physicians’ involvement in care processes for AL/RC residents is crucial but often unclear. While not comprehensive, this review aims to amplify a topic that remains fragmented, yet intimately tied to AL/RC resident care and well-being. Since every state has different AL/RC regulations and specifications of physician responsibilities, future research is necessary to describe the differences across states and implications for physician practices and resident care. AL/RC settings provide varying levels of care services to residents, ranging from assistance with chores to clinical care and hospice aimed to support resident autonomy (Kane & Mach Jr., 2007; Zimmerman & Sloane, 2007). Compared to licensed healthcare settings, AL/RC staff have less clinical training, rendering the role of physicians particularly important.

Caring for AL/RC residents involves balancing clinically desirable goals with residents’ preferences and values (McConnell & Meyer, 2019). All care team members must understand how to support informed choices for those in their care to ensure resident well-being and cooperation (Calkins & Brush, 2016). The relationship between residents and their physicians is influenced by care staff, nurses, specialists, and families (Kemp et al., 2019; Schumacher, 2006). While few states require a medical director, most require physician assessment at move-in and after change in condition or at regular intervals thereafter (National Center for Assisted Living [NCAL], 2019). Models of conferencing and monitoring care transitions between acute and post-acute settings suggest improved communication, increased access to comprehensive information, and fewer medication errors (Farris et al., 2016) providing a potential avenue for physician engagement in AL/RC. By participating on an interprofessional team for residents’ care coordination, physicians and AL/RC operators can work together to ensure person-centered care coordination and role definition (Nyrop et al, 2011; Young & Siegel, 2016). Communication, follow-up, and interprofessional care coordination are critical to AL/RC residents’ health and healthcare and physician roles must be further clarified through research, policy, and innovative practice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. John G. Schumacher at the University of Maryland Baltimore County and Dr. Martin Lipsky at Portland State University’s Institute on Aging for their thoughtful review and comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Publication of this article in an open access journal was funded by the Portland State University Library’s Open Access Fund.

ORCID iDs: Sarah Dys  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4310-3048

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4310-3048

Lindsey Smith  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4630-3114

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4630-3114

References

- Algase D. L., Beck C., Kolanowski A., Whall A., Berent S., Richards K., Beattie E. (1996). Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: An alternative view of disruptive behavior. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 11(6), 10–19. 10.1177/153331759601100603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2020). 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 16(3), 391–460. 10.1002/alz.12068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Hospital Association. (2013). Workforce roles in redesigned primary care model. www.aha.org/sites/default/files/aone/primary-care-workforce-needs.pdf

- Armstrong H., Armstrong P., MacLeod K. (2016). The threats of privatization to security in long-term residential care. Ageing International, 41(1), 99–116. 10.1007/s12126-015-9228-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Assisted Living Workgroup. (2003). Assuring quality in assisted living: Guidelines for federal and state policy, state regulations, and operations. A report to the U.S. Senate Special Committee On Aging. www.theceal.org/images/alw/AssistedLivingWorkgroupReport-April2003-with-appendices.pdf

- Ball M. M., Perkins M. M., Whittington F. J., Connell B. R., Hollingsworth C., King S. V., Elrod C. L., Combs B. (2004). Managing decline in assisted living: The key to aging in place. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 59(4), 202–212. 10.1093/geronb/59.4.S202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M., Kemp C., Hollingsworth C., Perkins M. (2014). “This is our last stop”: Negotiating end-of-life transitions in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 30, 1–13. 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck E. R., McIlfatrick S., Hasson F., Leavey G. (2015). Healthcare professionals’ perspectives of advance care planning for people with dementia living in long-term care residences: A narrative review of the literature. Dementia, 16(4), 486–512. 10.1177/1471301215604997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeber A. S., Zimmerman S., Mitchell M., Reed D. (2018). Staffing and service availability in assisted living: The importance of nurse delegation policies. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(11), 2158–2166. 10.1111/jgs.15580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett K. A., Ong T., Verrall A. M., Vitiello M. V., Marcum Z. A., Phelan E. A. (2018). Project ECHO-geriatrics: Training future primary care providers to meet the needs of older adults. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10(3), 311–315. 10.4300/JGME-D-17-01022.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berish D. E., Applebaum R., Straker J. K. (2018). The residential long-term care role in health care transitions. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(12), 1472–1489. 10.1177/0733464816677188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biola H., Sloane P. D., Williams C. S., Daaleman T. P., Williams S. W., Zimmerman S. (2007). Physician communication with family caregivers of long-term care residents at the end of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(6), 846–856. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Wilson K. (2007). Historical evolution of assisted living in the United States, 1979 to present. The Gerontologist, 47(Supp1), 8–22. 10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H., Arasaratnam C. (2012). Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(9), 946–953. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke J., Jackson D. (2020). Older people and COVID-19: Isolation, risk, and agism. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2044–2046. 10.1111/jocn.15274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E. E., Kumar S., Rajji T. K., Pollock B. G., Mulsant B. H. (2020). Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(7), 712–721. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucy T., Smith L., Carder P., Winfree J., Thomas K. (2020). Variability in state regulations pertaining to infection control and pandemic response in US assisted living communities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(5), 701–702. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt J., Rick J., Blakeman T., Protheroe J., Roland M., Bower P. (2014). Care plans and care planning in long-term conditions: A conceptual model. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 15(4), 342–354. 10.1017/S1463423613000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C., Cairns C., Rome V. (2020). Trends in electronic health record use among residential care communities: United States 2012, 2014, 2016. National Health Statistics Reports, 140. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr140-508.pdf [PubMed]

- Calkins M., Brush J. (2016). Honoring individual choice in long-term residential communities when it involves risk: A person-centered approach. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 42(8), 12–17. 10.3928/00989134-20160531-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder P. C. (2002). The social world of assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(1), 1–18. 10.1016/S0890-4065(01)00031-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carder P. C., Hernandez M. (2004). Consumer discourse in assisted living. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 59(2), S58–S67. 10.1093/geronb/59.2.S58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder P. C., O’Keeffe J., O’Keeffe C. (2015). Compendium of residential care and assisted living regulations and policy: 2015 edition. RTI International; https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/compendium-residential-care-and-assisted-living-regulations-and-policy-2015-edition [Google Scholar]

- Carder P. C., O’Keeffe J., O’Keeffe C., White E., Wiener J. M. (2016). State regulatory provisions for residential care residences: An overview of staffing requirements. RTI International; www.rti.org/sites/default/files/resources/rti-publication-file-2b8bcdd9-32ba-4ca2-9ba4-81b77dc86108.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Carder P. C., O’Keeffe J. (2016). State regulation of medication administration by unlicensed assistive personnel in residential care and adult day services residences. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 9(5), 209–222. 10.3928/19404921-20160404-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra P. T., Rattinger G. B., Dutcher S. K., Hare M. E., Parsons K. L., Zuckerman I. H. (2012). Medication reconciliation during the transition to and from long-term care residences: A systematic review. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 8(1), 60–75. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catic A. G., Mattison M. L. P., Bakaev I., Morgan M., Monti S. M., Lipsitz L. (2014). ECHO-AGE: An innovative model of geriatric care for long-term care residents with dementia and behavioral issues. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(12), 938–942. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin R., Dobbs-Kepper D. (2001). Aging in place in assisted living: Philosophy versus policy. The Gerontologist, 41(1), 43–50. 10.1093/geront/41.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. L., Brown J. W., Mefford L. C., de La Roche A., McLain A. M., Haun M. W., Persell D. J. (2008). Elders’ decisions to enter assisted living facilities: A grounded theory study. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 22(1–2), 86–103. 10.1080/02763890802097094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chyr L. C., Drabo E. F., Fabius C. D. (2020). Patterns and predictors of transitions across residential care communities and nursing homes among community-dwelling older adults in the United States. The Gerontologist, 60, 1495–1503. 10.1093/geront/gnaa070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J., Dakheel-Ali M., Marx M. S., Thein K., Regier N. G. (2015). Which unmet needs contribute to behavior problems in persons with advanced dementia? Psychiatry Research, 228(1):59–64. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell P. Y., Zhang W., Smith L., Fashaw S., Thomas K. S. (in press). Developments in the market for assisted living: Residential care availability in 2017. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cornell P. Y., Zhang W., Thomas K. S. (2020). Changes in long-term care markets: Assisted living supply and the prevalence of low-care residents in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(8), 1161–1165.e. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson E., Blaszczyk A. T. (2016). Assisted living facilities: The next frontier for consultant pharmacists. Consultant Pharmacist, 31(2), 107–11. 10.4140/TCP.n.2016.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel H., Sulmasy L. S, Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. (2015). Policy recommendations to guide the use of telemedicine in primary care residences: An American College of Physicians position paper. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(10), 787–789. 10.7326/M15-0498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S., Fortner J., Travis S. S. (2002). Barriers, challenges, and opportunities related to the provision of hospice care in assisted-living communities. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 19(3), 187–192. 10.1177/104990910201900310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D., Hanson L., Zimmerman S., Williams C. S., Munn J. (2006). Hospice attitudes among assisted living and nursing home administrators, and the long-term care hospice attitudes scale. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(6), 1388–1400. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D., Kaufman S., Meng H. (2018). The association between assisted living direct care worker end-of-life training and hospice use patterns. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 4, 1–5. 10.1177/2333721418765522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D., Peterson L., Hyer K. (2020). The unique challenges faced by assisted living communities to meet federal guidelines for COVID-19. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 32(4–5), 334–342. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1770037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosa D., Jump R. L. P., LaPlante K., Gravenstein S. (2020). Long-term care facilities and the coronavirus epidemic: Practical guidelines for a population at highest risk. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 21(5), 569–571. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty M., Harris P. S., Teno J., Corcoran A. M., Douglas C., Nelson J., Way D., Harrold J. E., Casarett D. J. (2015). Hospice care in assisted living facilities versus at home: Results of a multisite cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(6), 1153–1157. 10.1111/jgs.13429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer L. L., Carder P. C., Harris-Kojetin L. (2014). Medication management services offered in U.S. Residential Care Communities. Seniors Housing and Care Journal, 22(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dys S., Tunalilar O., Carder P. C. (2020). Correlates of administrator tenure in US residential care communities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(3), 351–354.e4. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby D. W., Molnar L. J., Kostyniuk L. P., St. Louis R. M., Zanier N. (2017). Characteristics of informal caregivers who provide transportation assistance to older adults. PLoS ONE, 12(9), e0184085 10.1371/journal.pone.0184085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P. A., Spencer J., Paul T., Boardman J. B. (2016). The geriatrics in primary care demonstration: Integrating comprehensive geriatric care into the medical home: Preliminary data. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 64(4), 875–879. 10.1111/jgs.14026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris G., Sircar M., Bortinger J., Moore A., Krupp J. E., Marshall J., Abrams A., Lipsitz L., Mattison M. (2016). Extension for community healthcare outcomes—care transitions: Enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary video conference. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(3), 598–602. 10.1111/jgs.14690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick D. M., Semla T. P., Steinman M., Beizer J., Brandt N., Dombrowski R., DuBeau C. E., Pezzullo L., Epplin J. J., Flanagan N., Morden E., Hanlon J., Hollman P., Laird R., Linnebur S., Sandhu S. (2019). American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(4), 674–694. 10.1111/jgs.15767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbon M., Lorenz R., Lach H. (2013). Medication reconciliation: reducing risk for medication misadventure during transition from hospital to assisted living. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 39(12), 22–29. 10.3928/00989134-20130930-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., Kane R. L., Kane R. A, Newcomer R. (2005). Unmet care needs and key outcomes in dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(12), 2098–2105. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00495.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., Kane R. L. (2007). Families and assisted living. The Gerontologist, 47(Suppl 1), 83–99. 10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill D., Almutairi S., Donyai P. (2019). “The lesser of two evils” versus “medicines not smarties”: Constructing antipsychotics in dementia. The Gerontologist, 59(3), 570–579. 10.1093/geront/gnx178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski D. C., Stevenson D. G., Cornell P. Y. (2012). Assisted living expansion and the market for nursing home care. Health Services Research, 47(6), 2296–2315. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01425.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M. J., Booth A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B. N., Johnson C. D., Adams A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101–117. 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein J. E., Policzer J. S., Shaban E. S. (2019). Hospice for the primary care physician. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 46(3), 303–317. 10.1016/j.pop.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber-Baldini A. L., Boustani M., Sloane P. D., Zimmerman S. (2004). Behavioral symptoms in residential care/assisted living facilities: Prevalence, risk factors, and medication management. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(10), 1610–1617. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwitz J. H., Kapoor A., Rochon P. A. (2018). Polypharmacy, the good prescribing continuum, and the ethics of deprescribing. Public Policy & Aging Report, 28(4), 108–112. 10.1093/ppar/pry033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy R. C. (2015). Do we need more geriatricians or better trained primary care physicians? Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 1, 1–2. 10.1177/2333721414567129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy R. C., Kinser A., Dickerson K., Kendall-Wilson T., Depelteau A., Copeland R., Whalen K. (2018). Insomnia and mild cognitive impairment. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 4, 1–9. 10.1177/2333721418778421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K., Trinkoff A. M., Storr C.L., Lerner N., Yang B. K. (2017). Variation across U.S. assisted living facilities: Admissions, resident care needs, and staffing. Journal Nursing Scholarship, 49(1), 24–32. 10.1111/jnu.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L. D., Sengupta M., Lendon J. P., Rome V., Valverde R., Caffrey C. (2019). Long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015–2016. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_43-508.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M. (2005). Assisted living in all its guises. Generations, 29(4), 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman S. E., Nelson C. A., Moss A. H., Hammes B. J., Terwilliger A., Jackson A., Tolle S. W. (2010). Use of the physician’s orders for life sustaining treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice residence. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(2), 133–141. 10.1089/jpm.2008.0196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman K. B., Hodgson N. A. (2018). Evidence-based interventions for transitions in care for individuals living with dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(Supp 1), 129–140. 10.1093/geront/gnx152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeier K. C., McDonough S. L. K., Rein L. J., Brookhart A. L., Gibson M. L., Powers M. F. (2019). Exploring the expanded role of the pharmacy technician in medication therapy management service implementation in the community pharmacy. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 59(2), 187–194. 10.1016/j.japh.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt J. D. (2017). Navigating long-term care. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 3, 1–5. 10.1177/2333721417700368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holup A. A., Dobbs D., Temple A., Hyer K. (2014). Going digital: Adoption of electronic health records in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 33(4), 494–504. 10.1177/0733464812454009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail Z., Smith E. E., Geda Y., Sultzer D., Brodaty H., Smith G., Agüera-Ortiz L., Sweet R., Miller D., Lyketsos C. G., ISTAART Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Professional Interest Area. (2016). Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: Provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12(2), 195–202. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P. D., Biggins M. S., Cowan L., French B., Hopkins S. L., Uphold C. R. (2016). Evidence summary and recommendations for improved communication during care transitions. Rehabilitation Nursing, 41(3), 135–148. 10.1002/rnj.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. W. (2017). What is the lifetime risk of needing and receiving long-term services and supports? Urban Institute; https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/what-lifetime-risk-needing-and-receiving-long-term-services-and-supports [Google Scholar]

- Kales H. C., Gitlin L. N., Lyketsos C. G, Detroit Expert Panel on the Assessment and Management of the Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. (2014). Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical residences: Recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62(4), 762–769. 10.1111/jgs.12730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. A., Wilson K. B. (1993). Assisted living in the United States: A new paradigm for residential care for frail older persons? American Association of Retired Persons, 47, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. L., Mach J. R., Jr. (2007). Improving health care for assisted living residents. The Gerontologist, 47(Supp_1), 100–109. 10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz P. R., Kronhaus A., Fuller S. (2018). The role of physicians practicing in assisted living: Time for change. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(2), 102–103. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp M. B. (1997). Who is responsible for this? Assigning rights and consequences in elder care. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 9(2), 51–65. 10.1300/J031v09n02_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C., Craft Morgan J., Kemp C. L., Deichert J. (2020). A profile of the assisted living direct care workforce in the United States. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(1), 16–27. 10.1177/0733464818757000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey S. G., Laditka S. B., Laditka J. N. (2010). Caregiver perspectives on transitions to assisted living and memory care. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 25(3), 255–264. 10.1177/1533317509357737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., Morgan J. C., Doyle P. J., Burgess E. O., Perkins M. M. (2018). Maneuvering together, apart, and at odds: Residents’ care convoys in assisted living. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73(4), 13–23. 10.1093/geronb/gbx184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., Perkins M. M. (2019). Individualization and the health care mosaic in assisted living. The Gerontologist 59(4), 644–654. 10.1093/geront/gny065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns J. W., Winter J. D., Winter K. M., Kerns C. C., Etz R. S. (2018). Caregiver perspectives about using antipsychotics and other medications for symptoms of dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(2), e35–e45. 10.1093/geront/gnx042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatutsky G., Ormond C., Wiener J. M., Greene A. M., Johnson R., Jessup E. A., Vreeland E., Sengupta M., Caffrey C., Harris-Kojetin L. (2016). Residential care communities and their residents in 2010: A national portrait (DHHS Publication No. 2016–1041; p. 78). National Center for Health Statistics; www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsrcf/nsrcf_chartbook.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lanctôt K. L., Amatniek J., Ancoli-Israel S., Arnold S. E., Ballard C., Cohen-Mansfield J., Ismail Z., Lyketsos C. G., Miller D. S., Musiek E., Osorio R. S., Rosenberg P. B., Stalin A., Steffens D., Tariot P., Bain L. J., Carrillo M. C., Hendrix J. A., Jurgens H., Boot B. (2017). Neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: New treatment paradigms. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 3(3), 440–449. 10.1016/j.trci.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liken M. (2001). Caregivers in crisis: Moving a relative with Alzheimer’s to assisted living. Clinical Nursing Research, 10(1), 52–68. 10.1177/c10n1r6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieto J. M., Schmidt K. S. (2005). Reduced ability to self-administer medication is associated with assisted living placement in a continuing care retirement community. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 6(4), 246–249. 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Look K. A., Stone J. A. (2018). Medication management activities performed by informal caregivers of older adults. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 14(5), 418–426. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos C. G., Lopez O., Jones B., Fitzpatrick A. L., Breitner J., Dekosky S. (2002). Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the cardiovascular health study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(12), 1475–1483. 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos C. G. (2007). Neuropsychiatric symptoms (behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia) and the development of dementia treatments. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(3), 409–420. 10.1017/S104161020700484X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. M. H. (2007). Assisted living: Where are we now and where are we going? Consultant Pharmacist, 22(6), 462–466. 10.4140/tcp.n.2007.462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell E. S., Meyer J. (2019). Assessing quality for people living with dementia in residential long-term care: Trends and challenges. Gerontology and Geriatrics Medicine, 5, 1–7. 10.1177/2333721419861198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitty E. (2009). Medication management in assisted living: A national survey of policies and practices. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 10(2), 107–114. 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead L. C., Eckert J. K., Zimmerman S., Schumacher J. G. (2005). Sociocultural aspects of transitions from assisted living for residents living with dementia. The Gerontologist, 45(Suppl_1), 115–123. 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. L., Patel K., Boscardin W. J., Steinman M. A., Ritchie C., Schwartz J. B. (2018). Medication burden attributable to chronic co-morbid conditions in the very old and vulnerable. PLoS ONE, 13(4): e0196109. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandi A., Davis D., Bellelli G., Arora R. C., Caplan G. A., Kamholz B., Kolanowski A., Fick D. M., Kreisel S., MacLullich A., Meagher D., Neufeld K., Pandharipandhe P. P., Richardson S., Slooter A. J. C., Taylor J. P., Thomas C., Tieges Z., Teodorczuk A., …Rudolph J. L. (2017). The diagnosis of delirium superimposed on dementia: An emerging challenge. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(1), 12–18. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L. A. (2009). Balancing safety and privacy: The case of room locks in assisted living. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 23(3), 185–203. 10.1080/02763890903035530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munchhof A., Gruber R., Lane K. A., Bo N., Rattray N. A. (2020). Beyond discharge summaries: Communication preferences in care transitions between hospitalists and primary care providers using electronic medical records. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35, 1789–1796. 10.1007/s11606-020-05786-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munroe D. J., Guihan M. (2005). Provider dilemmas with relocation in assisted living: Philosophy vs. practice. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 17(3), 19–37. 10.1300/J031v17n03_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Assisted Living [NCAL]. (2019). 2019 Assisted living state regulatory review. www.ahcancal.org/ncal/advocacy/regs/Documents/2019_reg_review.pdf

- Nyrop K. A., Zimmerman S., Sloane P. D. (2011). Physician perspectives on fall prevention and monitoring in assisted living: A pilot study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 12(6), 445–450. 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyrop K. A., Zimmerman S., Sloane P. D., Bangdiwala S. (2012). Fall prevention and monitoring of assisted living patients: An exploratory study of physician perspectives. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(5), 429–433. 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dwyer C. (2013). Official conceptualizations of person-centered care: Which person counts? Journal of Aging Studies, 27(3), 233–242. 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E. S., Rabins P. V. (2019). Dementia. Annals of Internal Medicine, 171(5), ITC33–ITC48. 10.7326/AITC201909030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanlon S., Inouye S. K. (2020). Delirium: A missing piece in the COVID-19 puzzle. Age & Ageing, 49(4), 497–498. 10.1093/ageing/afaa094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A., Shi Z., Ray K. N., Mehrotra A., Ganguli I. (2019). National trends in primary care visit use and practice capabilities, 2008–2015. Annals of Family Medicine, 17(6), 538–544. 10.1370/afm.2474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinardy J. R., Kane R. A. (2003). Anatomy of a choice: Deciding on assisted living or nursing home care in Oregon. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 22(1), 152–174. 10.1177/073346402250477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard S. C., Young H. M., Kane R. A., Quinn W. V. (2006). Nurse delegation of medication administration for older adults in assisted living. Nursing Outlook, 54(2), 74–80. 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B., Allen J., McMahon E. (2018). The role of physicians practicing in assisted living: What changes do we really need? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(2), 104–105. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads M., Thai A. (2003). Physician acceptance rate of pharmacist recommendations to reduce use of potentially inappropriate medications in the assisted living setting. The Consultant Pharmacist, 18(3), 241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rome V., Harris-Kojetin L., Carder P. (2019). Variation in licensed nurse staffing characteristics by state requirements in residential care. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 12(1), 27–33. 10.3928/19404921-20181212-03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T., Brunton S. (2019). Identification and management of insomnia in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Family Practice, 68(8), 32–38. 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscin J. M., Linnebur S. A. (2018, December). Drug-related problems in older adults. MERCK Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/geriatrics/drug-therapy-in-older-adults/drug-related-problems-in-older-adults

- Ryman F. V. M., Erisman J. C., Darvey L. M., Osborne J., Swartsenburg E., Syurina E. V. (2018). Health effects of the relocation of patients with dementia: A scoping review to inform medical and policy decision-making. The Gerontologist, 9(6), e674–e682. 10.1093/geront/gny031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales K., Zimmerman S., Miller S. J. (2018). Evidence-based nonpharmacological practices to address behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(Supp 1), 88–102. 10.1093/geront/gnx167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J. G., Eckert J. K., Zimmerman S., Carder P., Wright A. (2005). Physician care in assisted living: A qualitative study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 6(1), 34–45. 10.1016/j.jamda.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J. G. (2006). Examining the physician’s role with assisted living residents. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 7(6), 77–82. 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedhom R., Barile D. (2017). Teaching our doctors to care for the elderly: A geriatrics needs assessment targeting internal medicine residents. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 3, 1–3. 10.1177/2333721417701687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpp T., Young H. (2015). Experiences of frequent transfers to the emergency department by residents with dementia in assisted living. Geriatric Nursing, 36(1), 30–35. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee T. P. (2009). “But I am not moving”: Residents’ perspectives on transitions within a continuing care retirement community. The Gerontologist, 49(3), 418–427. 10.1093/geront/gnp030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver B. C., Grabowski D. C., Gozalo P. L., Dosa D., Thomas K. S. (2018). Increasing prevalence of assisted living as a substitute for private-pay long-term nursing care. Health Services Research, 53(6), 4906–4920. 10.1111/1475-6773.13021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikma S. K., Young H. M., Reinhard S. C., Munroe D. J., Cartwright J., McKenzie G. (2014). Medication management roles in assisted living. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40(6), 42–53. 10.3928/00989134-20140211-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane P. D., Zimmerman S., Perez R., Reed D., Harris-Wallace B., Khandelwal C., Beeber A. S., Mitchell M., Schumacher J. G. (2011). Physician perspectives on medical care delivery in assisted living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(12), 2326–2331. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03714.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M., Buckwalter K. (2005). Behaviors associated with dementia: Whether resisting care or exhibiting apathy, an older adult with dementia is attempting communication. Nurses and other caregivers must learn to “hear” this language. American Journal of Nursing, 105(7), 40–52. 10.1097/00000446-200507000-00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R. (2009). The physician’s role in long-term care culture change. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 10(8), 587–588. 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanacci R. G., Haimowitz D. (2012). Medication management in assisted living. Geriatric Nursing, 33(4), 304.e1–12. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R. I. (2006). Physician involvement in long-term care: Bridging the medical and social models. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 7(7), 460–466. 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach N., Wiener J. M. (2018). An overview of long-term services and supports and Medicaid: Final report. RTI International; https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/overview-long-term-services-and-supports-and-medicaid-final-report [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K. S., Belanger E., Zhang W., Carder P. C. (2020). State variability in assisted living residents’ end-of-life care trajectories. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 21(3), 415–419. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K. S., Zhang W., Cornell P. Y., Smith L., Kaskie B., Carder P. C. (2020). State variability in the prevalence of healthcare utilization of assisted living residents with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(7), 1504–1511. 10.1111/jgs.16410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjia J., Mazor K. M., Field T., Meterko V., Spenard A., Gurwitz J. H. (2009). Nurse-physician communication in the long-term care residence: Perceived barriers and impact on patient safety. Journal of Patient Safety, 5(3), 145–152. 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181b53f9b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toles M. P., Abbott K. M., Hirschman K. B., Naylor M. D. (2012). Transitions in care among older adults receiving long-term services and supports. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 38(11), 40–47. 10.3928/00989134-20121003-04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso J. V., Farinpour R., Chui H. C., Liu C. Y. (2016). A multidisciplinary model of dementia care in an underserved retirement community, made possible by telemedicine. Frontiers in Neurology, 7, 225 10.3389/fneur.2016.00225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff A. M., Yoon J. M., Storr C. L., Lerner N. B., Yang B. K., Han K. (2020). Comparing residential long-term care regulations between nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Nursing Outlook, 68(1), 114–122. 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin B. K., Loskutova N., Knicely P., Wood C. D. (2019). Tools for better dementia care. Family Practice Management, 26(1), 11–16. https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2019/0100/p11.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volicer L., Hurley A. C. (2003). Review article: Management of behavioral symptoms in progressive degenerative dementias. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 9(3), 837–845. 10.1093/gerona/58.9.M837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw G. A., Bragg E. J. (2016). The essential components of quality geriatric care. Generations, 40(1), 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Weckmann M. T. (2008). The role of the family physician in the referral and management of hospice patients. American Family Physician, 77(6), 807–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn P., Cook J. B., Bonnel W. (2004). Improving communication among attending physicians, long-term care facilities, residents, and residents’ families. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 5(2), 114–122. 10.1097/01.JAM.0000113430.64231.D9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf D. A., Jenkins C. (2014). Family care and assisted living: An uncertain future? In Golant S. M., Hyde J. (Eds.), The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. (pp 198–222). The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J. L., Spillman B. (2014). Older adults receiving assistance with physician visits and prescribed medications and their family caregivers: Prevalence, characteristics, and hours of care. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 69(Supp_1), S65–S72. 10.1093/geronb/gbu119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H., Fick D. (2020). Public health and ethics intersect at new levels with gerontological nursing in COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 46(5), 4–7. 10.3928/00989134-20200403-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H. M., Siegel E. O., McCormick W. C., Fulmer T., Harootyan L. K., Dorr D. A. (2011). Interdisciplinary collaboration in geriatrics: Advancing health for older adults. Nursing Outlook, 59(4), 243–250. 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H. M., Siegel E. O. (2016). The right person at the right time: Ensuring person-centered care. Generations, 40(1), 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Young H. M., Sikma S. K., Reinhard S. C., McCormick W. C., Cartwright J. C. (2013). Strategies to promote safe medication administration in assisted living settings. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 6(3), 161–170. 10.3928/19404921-20130122-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Sloane P. D. (2007). Definition and classification of assisted living. The Gerontologist, 47(Supp 1), 33–39. 10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Sloane P. D., Reed D. (2014). Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health Affairs (Millwood), 33(4), 658–666. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Cohen L., van der Steen J. T., Reed D., van Soest-Poortvliet M. C., Hanson L. C., Sloane P. D. (2015). Measuring end-of-life care and outcomes in residential care/assisted living and nursing homes. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(4), 666–679. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Cohen L. W., Washington T. M., Ward K., Giorgio P. (2016). Measures and instruments for quality improvement in assisted living. The Center for Excellence in Assisted Living; https://www.theceal.org/images/Measures-and-Instruments-for-Quality-Improvement-in-Assisted-Living_Final-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Sloane P. D., Katz P. R., Kunze M., O’Neil K., Resnick B. (2020). The need to include assisted living in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 21(5), 572–575. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]