Abstract

Objective

Major system change (MSC) has multiple, sometimes conflicting, goals and involves implementing change across a number of organizations. This study sought to develop new understanding of how the role that networks can play in implementing MSC, using the case of centralization of specialist cancer surgery in London, UK.

Methods

The study was based on a framework drawn from literature on networks and MSC. We analysed 100 documents, conducted 134 h of observations during relevant meetings and 81 interviews with stakeholders involved in the centralization. We analysed the data using thematic analysis.

Results

MSC in specialist cancer services was a contested process, which required constancy in network leadership over several years, and its horizontal and vertical distribution across the network. A core central team composed of network leaders, managers and clinical/manager hybrid roles was tasked with implementing the changes. This team developed different forms of engagement with provider organizations and other stakeholders. Some actors across the network, including clinicians and patients, questioned the rationale for the changes, the clinical evidence used to support the case for change, and the ways in which the changes were implemented.

Conclusions

Our study provides new understanding of MSC by discussing the strategies used by a provider network to facilitate complex changes in a health care context in the absence of a system-wide authority.

Keywords: Major system change, cancer surgery, networks

Background

Major system change (MSC) is defined as a ‘coordinated, system-wide change affecting multiple organizations and care providers, with the goal of making significant improvements in efficiency of health care delivery, the quality of patient care, and population-level patient outcomes’.1 Of growing importance and relevance internationally, examples of MSC include the centralization of specialist services to reduce variations in access, increase patient volumes and improve patient outcomes, as evidenced in cancer care.

There is increasing understanding of the impact of centralization in different areas of health care delivery,2–5 but there remain considerable gaps in knowledge about how MSC is planned and implemented. There may also be negative consequences of MSC as clinical teams, therapeutic relationships and collective identities may be disrupted, possibly without generating promised health care benefits for the population.6

In this article, we seek to develop new understanding of MSC implementation by analysing the centralization of specialist cancer surgery in London, UK. This change was developed and implemented by a network of National Health Service (NHS) provider organizations and involved centralization of services across four cancer pathways (bladder, prostate, renal, and oesophago-gastric cancers). Our main focus is the role of the provider-led network in managing the MSC. The case presents a departure from experiences of MSC in other areas of health care delivery in the UK, where regional system-wide organizations were previously identified as playing a central role in the implementation of MSC.2

We analyse the mechanisms and strategies used by network leaders and managers to implement MSC and develop new understanding of how these can influence its successful implementation. Defined as ‘formal and informal communication between diverse, but related, organizations to manage the flow of public services across the whole area of service provision’,7 networks can be used to work across institutional and professional boundaries, promoting joint working arrangements and the flow of knowledge, potentially improving patients’ access to and quality of care.8 Networks can also be inherently hierarchical, with some organizations in the network playing a more ‘dominant’ role in decision-making processes.9,10 They have the potential to address ‘wicked problems’, that is, problems requiring systemic response, behaviour change, and engagement across organizations.11

Our study explored the strategies used by a network of provider organizations to implement centralized specialist cancer surgery, considering network effectiveness in relation to the network’s ability to achieve this.8 We studied stakeholder preferences for centralizing services, the impact of the changes in relation to clinical, cost-effectiveness, patient experience and process outcomes.8,12

Centralizing specialist cancer surgery in London

The centralization of specialist cancer surgery followed the publication by the NHS Commissioning Support for London of the 2010 Case for Change and Model of Care for Cancer Services, which recommended the establishment of clinically led provider networks to optimize the whole pathway of cancer care and reduce variation.13,14 In 2012, a network of 12 provider organizations was commissioned to oversee the provision of cancer services for north east and north central London and west Essex (covering a population of 3.2 million). The aim was to improve cancer patients’ experience of care, increase access to a wider range of treatment options and participation in clinical trials, and, ultimately, to improve outcomes.15 One of the main changes planned by the network was the centralization of specialist surgical services.

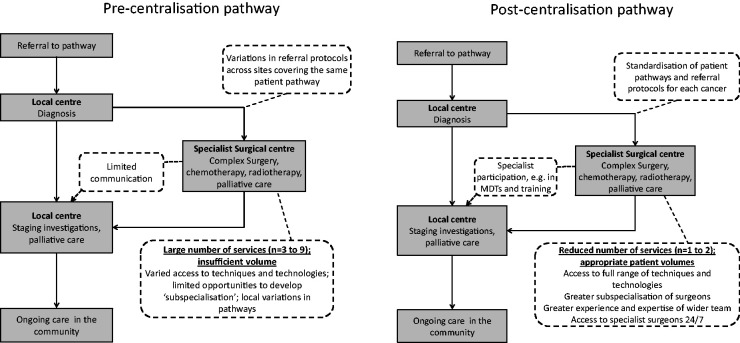

Pre-centralization, the number of centres providing specialist cancer surgery in London varied by pathway (for instance, nine in renal cancer and three in oesophago-gastric cancer) (Figure 1). Patients suspected of having cancer were referred to their local cancer centre for diagnostic testing; those diagnosed with cancer received treatment either at the same local cancer centre or were referred to a specialist centre. However, referral processes and the care received by patients varied across centres, with for example, robotic surgery for prostate and bladder cancer only available in certain specialist cancer surgery units. Surgery for renal cancer was performed in specialist and local non-specialist centres, potentially limiting the surgical options afforded to patients; also, patients were not guaranteed to see a specialist out of hours or at weekends. There was substantial variation in patient volumes across specialist centres and in the number of cases per surgeon.

The MSC involved reducing the number of centres delivering specialist cancer surgery from four to one for the prostate and bladder pathway, from nine to one for the renal pathway and from three to two for the oesophago-gastric pathway. Pathway boards led by clinical experts in the tumour type were established to oversee the service specifications of specialist and local centres and the implementation of the changes, and to monitor/improve care delivery. Pathway changes also introduced specialist multi-disciplinary teams (SMDTs) to facilitate clinical input from a wide range of professional groups across the network and to meet regularly with local multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) based at local centres to discuss patient cases. These meetings facilitated the coordination of patient care and sharing of expertise across the network of providers. All planned changes were fully implemented by April 2016.

Figure 1.

Illustrates pre and post centralization models of care that were implemented.

Methods

Data collection and sampling

We conducted a qualitative study using document review, non-participant observation and in-depth interviews from September 2015 to April 2019. The study focused on 10 sites in London, sampled as: (1) specialist centres, (2) sites that used to deliver specialist surgery but lost these services as a result of the centralization, and (3) sites that were local centres and remained local after the reconfiguration. Documentary evidence (100 documents) was gathered from online resources and from people involved in the planning and implementation of the centralization. We conducted non-participant observation (134 h) of relevant board meetings, SMDT meetings at specialist and local centres, and other events associated with the centralization. A sampling framework of potential participants to approach for interviews as well as relevant meetings to observe was developed in collaboration with staff who played a key role in the planning and implementation of the centralization. Observations were recorded in the form of unstructured field notes and through a structured observation guide. We interviewed stakeholders (n = 81) involved in the centralization of cancer surgery across London, identified through a review of documentary evidence on the changes and snowball sampling; participants were selected present a range of views on the MCS (Table 1). Only one participant refused to take part in the study.

Table 1.

Profile of interview participants.

| Participant group | Number |

|---|---|

| Network managers and other network staff members | 8 |

| Local contexta | 9 |

| Patient representatives | 3 |

| Urology Pathway Boardb members | 4 |

| Oesophago-gastric (OG) Pathway Boardb members | 4 |

| OG cliniciansc from provider organizations (specialist and local centres) | 14 |

| Urology cliniciansc from provider organizations (specialist and local centres) | 30 |

| OG managers from provider organizations (specialist and local centres) | 2 |

| Urology managers from provider organizations (specialist and local centres) | 7 |

aCommissioners (involved in the planning and purchasing of NHS and publicly funded social care services), academics, members from organizations outside of the network.

bPathway boards are led by clinical pathway directors and include representation from patients, primary care and cancer professionals from across the London area.

cSurgeons, nurses, oncologists, allied health professionals, pathologists and radiologists.

Potential interview participants were contacted by email or telephone and provided with a participant information sheet. Interviews were conducted in person or via telephone using an interview topic guide which covered the different stages of the centralization. The topic guide was designed in collaboration with staff who had played a key role in the planning and implementation of the centralization. Interviews lasted approximately 50 min and were audio recorded then professionally transcribed. Written informed consent was obtained at the beginning of each interview. Permission to observe meetings was obtained from the Chair in advance. Participants were given the option to opt out of observations. No members of staff opted out of the observations.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts, observation notes and documentary evidence were analysed using thematic analysis.16 Data from the interviews shed light on perceptions and experiences of the re-organization. The observations pointed to the ways in which the implementation was carried out in practice. The documentary analysis allowed us to capture retrospectively the early stages of centralization design and planning as well as the ‘official’ documents guiding implementation. We conducted an initial familiarization stage and identified preliminary codes. We then examined these codes in relation to our framework. Codes were grouped into themes concerning the main features guiding the planning and implementation of the centralization. We re-examined our framework based on these themes. Emerging findings were shared with a wide stakeholder group. Feedback was used to refine the focus of the analysis.

Ethical approval

The mixed-methods evaluation received ethical approval in July 2015 from the Proportionate Review Sub-committee of the NRES Committee Yorkshire & the Humber – Leeds (Reference 15/YH/0359).

Results

Our analysis of the stages involved in the design and implementation of the centralization pointed to a series of factors that contributed to the successful implementation of the re-organization. We describe these factors below.

Central network leadership drove the changes forward

As mentioned earlier, a network of provider organizations was commissioned to oversee the implementation of the centralization of specialist cancer surgery. A key facilitator of the implementation was the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) who was based at a local academic health science partnership (these partnerships bring together academic institutions, health care organizations, local authorities, industry and members from the third sector). Although a clinician by background, the CMO’s clinical specialty was not part of the centralization. The CMO was also based at an ‘independent’ organization, in the sense that it was not a part of the any of the provider organizations in the network. The CMO worked closely with a network board (an independent skills-based board formed of experts external to London and chaired by a former cancer patient). This Board was created to oversee a bidding process where provider organizations would be selected to host specialist centres. Where consensus was not achieved and competing bids were submitted by provider organizations, the proposals were reviewed externally by clinical experts selected by the Board. The Board then developed recommendations on the sites that should take on the role of specialist centres for each pathway. These were agreed by the chief executives and medical directors of the network provider organizations.

Our data showed that the CMO and chair of the Board were perceived by many managers and clinicians across the network as providing strong, objective leadership, with a clear vision and mandate to implement the changes outlined in the Model of Care. Some network members suggested that the relative independence of the CMO role and of some members of the Board allowed the central leadership of the network (that is, the CMO and the Board Chair) to be seen as ‘neutral’. However, as will be explained later, other actors in the network associated central leadership figures with dominant provider organizations, that is, those organizations that obtained most of the specialist cancer workload as a result of the reconfiguration. Constancy in network leadership (mainly the CMO and the Board Chair) over time was also perceived to have enabled the implementation of changes, even in light of the profound organizational restructuring of the health care system during and after the 2012 health and social care reform that took place in England as a whole at that time.

The central leadership team drew from existing evidence on the potential benefits of centralizing specialist cancer surgery and previous experiences of centralization as a way to justify the changes:

At the initial stages it was very much based on the evidence that we were putting together, we were driving it based on what you would probably drive most changes on, which is pure data. (LON 15, network manager)

Data were not always readily available, and some interview participants reported to have spent a considerable amount of time searching for and collating data and developing new sources when these were not available. There were some discussions about the quality, veracity, and inclusivity of the data used to guide decisions on the reconfiguration. Some local surgeons expressed concerns about how the data were used:

So we were easily the highest volume, best audited results, best research in the sector; that’s why we were particularly upset when renal cancer was given to [the specialist centre] who had no history of really renal cancer work at all. (LON 47, urology surgeon)

We were suddenly turning around to surgeons who had been operating 10, 15, 20 years of their career, doing the same procedure perhaps 50 to 100 times a year, and asking them to centralise their cases to [the specialist centre], who at the time, were only doing about 20 or 30 cases a year. So, there was the perception that it was very politically driven rather than an objective criteria-driven process. (LON 26, urology surgeon)

Network managers supported leaders

The CMO and Chair of the Board were central to the leadership, but staff members in managerial and clinical roles across other levels of the network also played an important role:

So, keeping the Chief Exec on board, keeping the Medical Directors on board, keeping the clinicians themselves on board and brought out, so all of those levels, so really try to make sure that the staff at ground level, knew that there was a place in this and that this was collective, working towards a shared ambition. (LON38, commissioning support staff member)

The network managers played an instrumental role in supporting leaders, mediating relationships across sites, and facilitating the day-to-day requirements of the changes. The Board appointed clinical leads to chair pathway boards and design the integrated cancer care pathways15:

So basically, we, being the [network] Board, prompted, encouraged, supported the pathway boards, which were almost entirely clinical, so that in a sense we gave them some degree of institutional coverage and support, external challenge through our Board members and a process under which they brought recommendations forward in a structured and disciplined way that addressed all the various things that needed to be addressed. (LON4, network board member)

The network core team designated, arranged training for, and supported leaders for each of the pathway boards; these leaders became a core leadership team that remained beyond the implementation of the changes. Leaders were selected for their skills in leading teams, engaging with a wide range of stakeholders, and building relationships, and changing culture. Leaders needed to act in hybrid roles, that is, combining clinical knowledge and managerial skills. An early planning document stated, ‘as we interview pathway directors, we will carefully screen for those with the leadership competencies to spread our culture quickly through the community’.17 The screening process was based on the use of competency models and role play simulations.17 The appointed leaders took part in personal leadership development sessions.

Engagement across provider organizations

The network encouraged the pathway leads to engage with a wide range of stakeholders within the network and ‘develop relationships with colleagues across the care pathway’.17 These relationships were considered central aspects of the objectives of the pathway leads and the leadership development programme mentioned above. Leaders used their own styles to create change. The successful implementation of the changes was associated with leaders who were viewed as trusted, had a clear vision, showed dedication and perceived as good at building relationships:

So, he was a tremendous leader […]. He was great at bringing people together, he was so unfazed and he wasn’t, he had no ego, he wasn’t brisk or brash or bold in what he was trying to do, he just worked quietly with everybody, he talked to them and said I want you involved. If you are not involved, you are choosing not to be. (LON 9, network manager)

Planning the changes entailed the inclusion of representatives from all provider organizations. There was an expectation that if all organizations were involved during early stages the implementation of the changes would be smoother as all organizations would have a sense of ownership of the new pathways, building momentum to drive the changes forward and sustain the changes over time.

However, engagement took place in a context interpreted by some as infused with competition for future surgical activity:

[T]here was a lot of concern from staff over the effect on their service’s future and sustainability and on a personal level, I think a lot of staff were concerned about their own personal practice and professional future. (LON 40, specialist centre staff member)

There was also a concern that specialist centres would be ‘taking over’ the network and absorbing all of the specialist care, leaving local centres without the ability to retain surgical expertise and recruit new members of staff.

Engagement of other stakeholders

Commissioners had a legal obligation to lead a public engagement process on the centralization.18 Following the 2012 reforms to the NHS in England, centralizations had to be authorized or approved by Clinical Commissioning Groups (newly formed payer organizations); the network Board could only make recommendations to commissioners. Whilst commissioners were kept informed in the early stages of planning, they only became more involved in 2013, when commissioning structures consolidated. Commissioners were involved in developing the reporting and governance mechanisms for the implementation of the changes (in the form of Gateway Reviews, a process by which programmes and projects are examined at key decision points in their lifecycle), and were also involved in carrying out two phases of an engagement process (late 2013 and in 2014), which comprised meetings with health care professionals, drop-in sessions for members of the public, and workshops.

I think when the new commissioning structures came in there was probably legal advice, strong legal advice to say, “If you want to have a really robust process, you need to be, have the commissioners working with this […].” The commissioners had a duty to look at those options with an open mind and review them and then make their own recommendations in an options appraisal. (LON36, Commissioning support staff member)

The engagement aimed to bring together a wide range of stakeholders to ‘gain their views and experience of current services and hear their aspirations for the health services they would receive in the future’.18 This engagement process included considering recommendations made by the Board as well as additional options not recommended by this Board (i.e. independent assessments). Patients, families and members of the public were asked about these changes through public meetings.

Some patient groups used this engagement process to express their concerns about the centralization plans. They felt the needs of patients would not be considered a priority in a centralized model of care; for example, some patients would be forced to travel for longer periods of time to undergo specialist surgery:

When you did raise any objections or problems, you felt you were being fobbed off, as I say, the reduced [travel] fares was the hilarious one, yeah, and it was more just, they were having discussions about getting extra parking spaces. We knew that from our other contacts with other groups and so on that East London and/or the eastern boroughs we call them, there was quite a resistance about going up west. (LON13, patient representative)

Patient representatives who had worked with members of the network and were in favour of the changes responded to these patients’ opposition by publicly highlighting the potentially positive effects of the changes on patient care, experience and health outcomes. Travel was recognized as a burden, but not a barrier to care: ‘my personal view is I think if you have got the best standards of treatment people will travel’ (LON10, patient representative).

Discussion

Our analysis of implementing the centralization of cancer surgical services across a network of providers in London combined existing knowledge about processes that facilitate MSC and the characteristics and strategies used by network leaders and managers to agree and create change. These changes were implemented after the major 2012 health care reform in England, in a context with substantially reduced system-wide, or ‘top-down’, authority. Our findings point to the role played by central network leadership figures and network managers in creating, supporting, and maintaining consensus in order to drive the changes. The network relied on key leadership figures as well as distributed, or more horizontal, forms of leadership across the network to bring together a diverse group of stakeholders and drive change. As in other types of health care networks, an emphasis on the ‘political neutrality’ of central network leaders and the Board was employed as a strategy to position themselves outside of the competitive health care landscape and drive the changes forward.9

Constancy in the people who enacted leadership roles allowed the network to drive the changes forward, even in the face of the organizational restructuring of the health care system. Senior clinical leaders who acted as pathway leads occupied hybrid leadership roles,19 where they assumed management responsibilities whilst retaining their clinical role. This granted them credibility within the network due to their clinical knowledge19 (also referred to as ‘reputational framing’)9 and allowed them to use their managerial skills to bridge organizational boundaries and bring together representatives from multiple professional groups.8

Clinical leadership of the changes was prioritized and actively fostered, as clinicians were strategically recruited and trained as leaders, developing their hybrid roles. Leadership training was based on inclusive models of participation in the changes and gave clinicians the skills to create ‘buy-in’ across sites and bring stakeholders on board. The work of these clinical leaders depended heavily on the support provided by programme-level network managers, who acted as facilitators, connections or bridges across organizations and professional groups.

Early engagement of a wide range of stakeholders led to the creation of local champions across different layers and sectors of the networks, building up the pressure to drive change. Fitzgerald et al. have discussed the role played by this cumulative effect of distributed leadership on organizational change and service improvement, where leadership enacted across multiple tiers creates a driving force to move events in a particular direction and sustain these changes through time.20 The changes were fully implemented, but many clinicians and managers continued to express disagreement with the rationale for the centralization, the evidence used to justify the changes and the ways in which the changes were made (i.e. how sites were selected to act as specialist centres), even several years after implementation.

Consistent with other studies of MSC,3,21 we found that patient and public involvement served various purposes, from a genuine interest in ensuring that the needs and interests of patients were represented in the planning and implementation of the changes, to more instrumental forms of involvement (i.e. to minimize resistance or act as champions). Engagement of commissioners was difficult in early stages, because of the wider system reform that involved a reorganization of commissioning landscape in England, as noted earlier.

Limitations

The retrospective nature of some of the interviews meant they could have been influenced by recall bias. To reduce the risk of bias, we used documentary evidence to complement interviewees’ narration of past events. We made an effort to maintain an inclusive sampling strategy, but we might have overlooked relevant individuals. Our study analysed the implementation of MSC in a specific health care area and in a predominantly urban setting; additional work is required to explore the role of provider networks in MSC in other specialties and contexts.

Conclusions

Our study of the role of the network in the centralization of specialist cancer surgery has shed light on the strategies that may be used by networks of provider organizations to implement MSC in health care contexts in the absence of a system-wide authority. Our study extends previous frameworks developed for the study of MSC, which pointed to the need for a combination of top-down and bottom-up leadership to implement MSC1,12 by describing the role networks can play in facilitating MSC, and the processes of negotiation involved in the implementation of such changes.

In the case of our study, MSC in specialist cancer was a contested process, where actors across the network, including clinicians and patients, questioned the rationale for the changes, the clinical evidence behind it, and the ways in which the changes were made. A core central team composed of network leaders, managers and clinical/manager hybrid roles was able to drive the changes forward by developing different forms of engagement with provider organizations, distributing leadership across vertical and horizontal layers, and maintaining constancy in central leadership over time.

As health care systems across the world turn to networks as a potentially valuable organizational model for health care delivery,22 greater attention needs to be paid to the role of these networks in transforming care, and which factors influence/facilitate their contribution. Future research should focus on the impact of such organizational forms on patient and population outcomes and the identification of network leadership styles that might be more successful in delivering MSC.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution made to this article by Neil Cameron, one of the patient representatives on this study, who died in May 2017. They also thank Ruth Boaden, Veronica Brinton, David Holden, Patrick Fahy, Michael Aitchison and Colin Jackson for their contributions to the development of this study, and Beck Taylor for feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KPJ is the chief medical officer of the network, MMM was Director of the OG Cancer Pathway Board for the network and Consultant Upper GI surgeon at UCLH, JH was pathway lead and CL was a pathway manager on the centralizations, and therefore have an interest in the successful implementation of MSC. DCS is the Medical Director of Greater Manchester Cancer and was involved in the engagement and design aspects of the Greater Manchester proposals working for Commissioners; he has no financial interests.

Ethics approval: The mixed-methods evaluation received ethical approval in July 2015 from the Proportionate Review Sub-committee of the NRES Committee Yorkshire & the Humber – Leeds (Reference 15/YH/0359).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Programme, funded by the Department of Health (study reference 14/46/19). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

ORCID iDs

Cecilia Vindrola-Padros https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7859-1646

Sarah Darley https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5420-6774

Caroline S Clarke https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4676-1257

References

- 1.Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, et al. Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q 2012; 90: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner S, Goulding L, Denis J, et al. Major system change: a management and organisational research perspective. In: Challenges, solutions and future directions in the evaluation of service innovations in health care and public health Health Services and Delivery Research. NIHR Journals Library, 2016. [PubMed]

- 3.Martin GP, Carter P, Dent M. Major health service transformation and the public voice: conflict, challenge or complicity? J Health Serv Res Policy 2018; 23: 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinder R, Petchey R, Shaw S, et al. What’s in a care pathway? Towards a cultural cartography of the new NHS. Sociol Health Illness 2005; 27: 759–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fulop NJ, Ramsay AIG, Perry C, et al. Explaining outcomes in major system change: a qualitative study of implementing centralised acute stroke services in two large metropolitan regions in England. Implement Sci 2016; 11: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones L, Fraser A, Stewart E. Exploring the neglected and hidden dimensions of large-scale healthcare change. Sociol Health Illn 2019; 41: 1221–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Addicott R, McGivern G, Ferlie E. The distortion of a managerial technique? The case of clinical networks in UK health care. Br J Manage 2007; 18: 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown B, Patel C, McInnes E, et al. The effectiveness of clinical networks in improving quality of care and patient outcomes: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 360–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waring J, Crompton A. The struggles for (and of) network management: an ethnographic study of non-dominant policy actors in the English healthcare system. Public Manage Rev 2020; 22: 297–315.

- 10.Muller-Seitz G. Leadership in interorganizational networks: a literature review and suggestions for future research. Int J Manage Rev 2012; 14: 428–443. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlie E, Fitzgerald L, McGivern G, et al. Public policy networks and ‘wicked problems’: a nascent solution? Public Admin 2011; 89: 324–387. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner S, Ramsay AI, Perry C, et al. Lessons for major system change: centralisation of stroke services in two metropolitan areas of England. J Health Serv Res Policy 2016; 21: 156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS Commissioning Support for London. A model of care for cancer services: Clinical paper. London: NHS Commissioning Support for London; http://www.londoncancer.org/media/11816/cancer-model-of-care.pdf (2010, accessed 16 March 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Commissioning Support for London. Cancer services case for change. London: NHS Commissioning Support for London, http://www.londoncancer.org/media/11798/cancer-case-for-change.pdf (2010, accessed 16 March 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 15.London Cancer. London cancer annual review 2012/2013, http://www.londoncancer.org/media/59497/London-Cancer-Annual-Review-2012-13.pdf (2013, accessed 16 March 2020).

- 16.Ritchie J, Spencer L, O’Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis In: Ritchie JLJ. (ed.) Qualitative research practice. London: Sage, 2003, pp.219–262. [Google Scholar]

- 17.London Cancer. London cancer: Integrated cancer system plan, http://www.londoncancer.org/media/62058/london-cancer-moa-2013-14.-final.pdf (2011, accessed 16 March 2020).

- 18.NHS England. Engagement feedback report: Phase two engagement, https://www.england.nhs.uk/london/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2014/07/er-app-e.pdf (2014, accessed 16 March 2020).

- 19.Ferlie E, McGivern G, Fitzgerald L. A new mode of organizing in health care? Governmentality and managed networks in cancer services in England. Soc Sci Med 2012; 74: 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzgerald L, Ferlie E, McGivern G, et al. Distributed leadership patterns and service improvement: Evidence and argument from English healthcare. Leadersh Q 2013; 24: 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKevitt C, Ramsay AIG, Perry C, et al. Patient, carer and public involvement in major system change in acute stroke services: the construction of value. Health Expect 2018; 21: 685–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Provan K, Kenis P. Modes of network governance: structure, management, and effectiveness. J Public Admin Res Theory 2007; 18: 229–252. [Google Scholar]