Abstract

The wide variation in size and content of eukaryotic genomes is mainly attributed to the accumulation of repetitive DNA sequences, like microsatellites, which are tandemly repeated DNA sequences. Sea turtles share a diploid number (2n) of 56, however recent molecular cytogenetic data have shown that karyotype conservatism is not a rule in the group. In this study, the heterochromatin distribution and the chromosomal location of microsatellites (CA)n, (GA)n, (CAG)n, (GATA)n, (GAA)n, (CGC)n and (GACA)n in Chelonia mydas, Caretta caretta, Eretmochelys imbricata and Lepidochelys olivacea were comparatively investigated. The obtained data showed that just the (CA)n, (GA)n, (CAG)n and (GATA)n microsatellites were located on sea turtle chromosomes, preferentially in heterochromatic regions of the microchromosomes (mc). Variations in the location of heterochromatin and microsatellites sites, especially in some pericentromeric regions of macrochromosomes, corroborate to proposal of centromere repositioning occurrence in Cheloniidae species. Furthermore, the results obtained with the location of microsatellites corroborate with the temperature sex determination mechanism proposal and the absence of heteromorphic sex chromosomes in sea turtles. The findings are useful for understanding part of the karyotypic diversification observed in sea turtles, especially those that explain the diversification of Carettini from Chelonini species.

Keywords: Cheloniidae, chromosomal rearrangements, Cryptodira, endangered species, repetitive DNAs

Introduction

Sea turtles (Testudines: Cryptodira) are grouped into Dermochelyidae and Cheloniidae families and only seven living species (Pritchard, 1997). Dermochelyidae is monotypic, represented by Dermochelys coriacea (leatherback sea turtle), and is the sister-taxon to a clade comprising all other extant sea turtles (Bowen and Karl, 1996; Dutton et al., 1996; Parham and Fastovsky, 1997; Iverson et al., 2007). Molecular phylogenetic studies supported recognition of two tribes in Cheloniidae: (i) Chelonini grouping Natator depressus (flatback sea turtle) and Chelonia mydas (green sea turtle) and; (ii) Carettini grouping Lepidochelys olivacea (olive ridley sea turtle), Lepidochelys kempii (Kemp’s ridley sea turtle), Eretmochelys imbricata (hawksbill sea turtle) and, Caretta caretta (loggerhead sea turtle) (Iverson et al., 2007; Naro-Maciel et al., 2008).

All sea turtle species show different levels of threat of extinction and are considered flag species for the conservation of biodiversity (IUCN, 2020) since numerous threats affect the populations maintenance (Lara-Ruiz et al., 2006; Proietti et al., 2014; Arantes et al., 2020). In addition, chromosomal studies in turtles demonstrated great karyotypic diversification among evolutionary lineages, making the cytogenetic knowledge important for recognition of species diversity and conservation (Valenzuela and Adams, 2011; Montiel et al., 2016; Rovatsos et al., 2017; Cavalcante et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Deakin and Ezaz, 2019; Clemente et al., 2020; Viana et al., 2020).

Testudines cytogenetic studies demonstrated karyotypes composed of macrochromosomes and a variable number of microchromosomes (mc), a characteristic shared with birds and squamate reptiles (Olmo, 2008; Pokorná et al., 2011a; Montiel et al., 2016). In turtles, three karyotypic groups were proposed according to the diploid number (2n): (i) high 2n (60 - 68 chromosomes) and high amount of mc; (ii) intermediate 2n (50 - 56 chromosomes) and relatively low amount of mc and; (iii) low 2n (26 - 28 chromosomes) and without mc (Ayres et al., 1969; Barros et al., 1976; Sites et al., 1979). However, genomic and cytogenetic studies using comparative analyses of chromosomal markers are scarce in Testudines species (Iannucci et al., 2019; Cavalcante et al., 2018, 2020a, b).

The wide variation of 2n (26 - 68 chromosomes) observed in turtles implies that their genomes have been deeply reorganized (Noleto et al., 2006; Valenzuela and Adams, 2011; Montiel et al., 2016; Noronha et al., 2016; Cavalcante et al., 2018, 2020a, 2020b; Clemente et al., 2020). In this sense, the characterization of repetitive DNA sequences present in heterochromatin sites allow us to understand chromosomal rearrangements in some species of the group (Cavalcante et al., 2018, 2020a, 2020b). In turtles, as well as in sister groups, heterochromatin is located in the pericentromeric region of most macrochromosomes and some mc (Nishida et al., 2013; de Oliveira et al., 2017; Cavalcante et al., 2018; Barcellos et al., 2019; Viana et al., 2020). In crocodilians, which do not have mc, the heterochromatic regions were also preferentially located in the pericentromeric regions (Amavet et al., 2003; Kawagoshi et al., 2008).

Heterochromatin is usually composed by an enriched repetitive DNA segment of satellite DNAs (Sumner, 2003). Satellite, minisatellites and microsatellites DNAs were initially classified according to both the length of the whole repeat cluster and the size of the repetitive unit (Tautz, 1993). Although controversy still exists, the term satellite DNA has been applied to any tandem repetitive sequence which is present in blocks of hundreds to thousands of units and which are located in heterochromatin sites regardless of unit size (Garrido-Ramos, 2015). For instance, microsatellites are 1-6 nucleotide units tandemly repeated and can be found accumulated as a part constituent of heterochromatin (Kubat et al., 2008; Schemberger et al., 2019; Viana et al., 2020; Zattera et al., 2020) or located dispersed in euchromatic chromosomes regions (Tóth et al., 2000; Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015). Their location on chromosomes can be species-specific or present a similar distribution pattern in close relationship species groups (Tóth et al., 2000; Ziemniczak et al., 2014; Pucci et al., 2016).

Based on phylogenetic analysis in Testudines, Montiel et al. (2016) proposed that the putatively ancestral condition for Dermochelyidae and Cheloniidae species is a 2n of 56 chromosomes (Figure 1). In previous studies, all sea turtle species shared 2n = 56 and their karyotypes were considered identical (Bickham et al., 1980; Bickham and Carr, 1983; López et al., 2008; Fukuda et al., 2014). However, a recent comparative cytogenetic study showed species-specific differences in chromosomal morphology, G-banding patterns, besides interstitial telomeric sites (ITS) occurrence, among C. mydas, L. olivacea, E. imbricata and, C. caretta, which ruled out the proposal of conserved structure of the macrochromosomes in Cheloniidae (Machado et al., 2020). Here, chromosomal data of sea turtle species from Cheloniidae that occur in the Brazilian coast: C. mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata, and L. olivacea were comparatively analyzed, aiming to describe the heterochromatin and microsatellites chromosomal locations, inferring its relations with the interspecific karyotype diversity.

Figure 1 - . Phylogeny, sampled area, and details of chromosome changes in four Cheloniidae species: In (a) phylogeny and ancestral reconstruction of sea turtle species adapted from Pereira et al. (2017); In (b), representative idiograms of the pairs 4, 5, 7 and 12 involved in chromosomal changes among sea turtle species; and (c) partial map of South America showing sea turtles sampled in different places in the Brazil and referred by geometric forms, C. mydas (circle), E. imbricatta (pentagon), C. caretta (asterisk), and L. olivacea (square). Images of sea turtles (Source: Projeto Tamar).

Material and Methods

Sampling and chromosome preparation

Chelonia mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea were cytogenetically compared. The biological samples were obtained captive or wild animals in different areas of the Brazilian coast (Figure 1; for details, see Table S1). Fifty sea turtles were sampled and karyotyped: (i) C. mydas (N = 27; one female and 26 juveniles), (ii) C. caretta (N = 11; two males, five females and four juveniles), (iii) E. imbricata (N = 6; two females and four juveniles ), and (iv) L. olivacea (N = 6; one male and five juveniles). The collection samples were authorized by the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio, licence number 52218-7; 43433-2/3). All experimental procedures were authorized and performed following the Ethical Committee on Animal Use of the Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa. (Protocol: 7200/2016).

Peripheral blood was used to obtain the chromosomal preparations by temporary culture of lymphocytes method (Rodríguez et al., 2003). The slides containing chromosomal preparations were submitted to C-banding for constitutive heterochromatin detection (Sumner, 1972) and to fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays, using microsatellites probes.

FISH

The (CA)15, (GA)15, (CAG)10, (GATA)8, (GAA)10, (CGC)10 and (GACA)8 microsatellites probes were directly labelled with Cy5 fluorochrome (Sigma-Aldrich, San Luis, Missouri, USA) at the 5’ end during DNA synthesis. FISH was performed according to the protocol proposed by Kubat et al. (2008), under ~77% stringency. Chromosomes were counterstained with 0.2 μg/mL 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole - DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) in the Vectashield mounting medium (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA). The images were captured in CCD Olympus DP-72 camera coupled in epifluorescence microscope Olympus BX51 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Twenty metaphases were analyzed per sampled individual for microsatellites signals detection.

Karyotype organization

Chromosomes were arranged by decreasing size and centromere position, as described by Montiel et al. (2016). They were classified as bi-armed and one-armed (acrocentric), depending on their arm ratio, and as macrochromosomes or mc, according to Bickham et al. (1980) description. Microchromosomes were remarkably similar (practically indistinguishable) and thus were ordered by approximate size and chromosome marks, where possible. Representative idiograms of the karyotype organization of the four species analyzed were designed, illustrating the data obtained in the present study and those of Machado et al. (2020).

Results

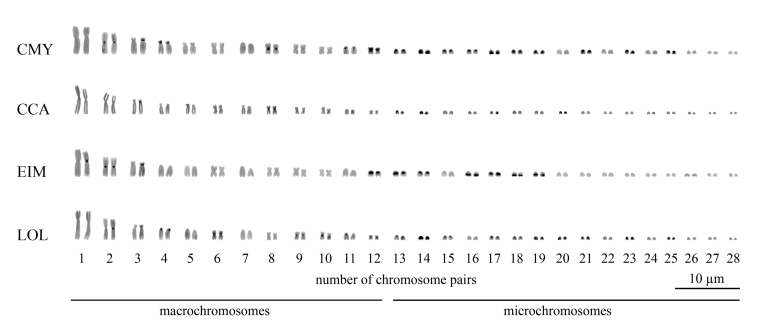

Constitutive heterochromatin organization

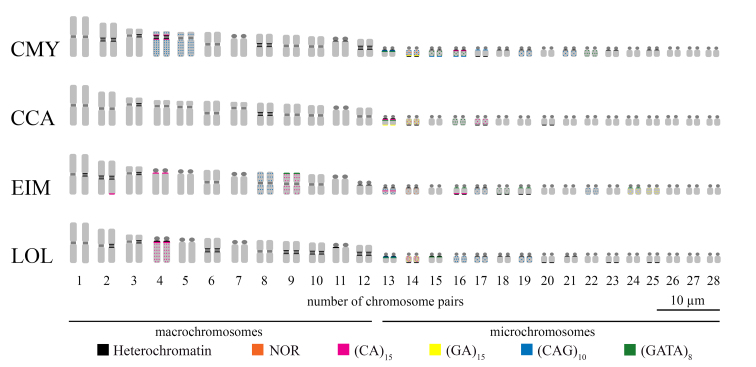

The four species presented 2n = 56 arranged in 12 macrochromosome and 16 mc pairs and without evidences for heteromorphic sex chromosomes occurrence among all individuals sampled (Figures 2-7). Chelonia mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea showed few heterochromatic blocks in the karyotypes, as follows: (i) C. mydas showed heterochromatic blocks in the pericentromeric regions of macrochromosomes 2-4, 8, 11 and 12, besides in the pericentromeric regions of mc long arms 13-19, 21, 23 and 25 (Figures 2 and 3); (ii) C. caretta has heterochromatic blocks in the pericentromeric regions of macrochromosomes 3 and 8, as well as in the pericentromeric region of mc 13 and, in the long arm of mc 14, 17 and 20 (Figures 2 and 3); (iii) E. imbricata showed heterochromatic bands located in the pericentromeric regions of the macrochromosomes 1-3 and 12, besides in the pericentromeric regions of mc 13, 14, and 17 and, in the subterminal region of the long arm of mc 16, 18 and 19 (Figures 2 and 3); and (iv) in L. olivacea heterochromatin is located in the pericentromeric regions of the macrochromosomes 2-4, 6 and 9-12, as well as in the pericentromeric regions of mc 13, 15, 17-19 and 21 and, in the long arms of mc 14, 20, 23 and 25 (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2 - . Representative idiograms of heterochromatic regions, NOR and microsatellite motifs on the chromosomes of the four sea turtle species. The species names were referred by their 3-letter acronym: C. mydas (CMY), C. caretta (CCA), E. imbricata (EIM) and L. olivacea (LOL).

Figure 7 - . Karyotypes of sea turtle species subjected to FISH using (GATA)8 microsatellites probes (red signals). The species names were referred by their 3-letter acronym: C. mydas (CMY), C. caretta (CCA), E. imbricata (EIM) and L. olivacea (LOL).

Figure 3 - . Karyotypes of sea turtle species subjected to C-banding. The species names were referred by their 3-letter acronym: C. mydas (CMY), C. caretta (CCA), E. imbricata (EIM) and L. olivacea (LOL).

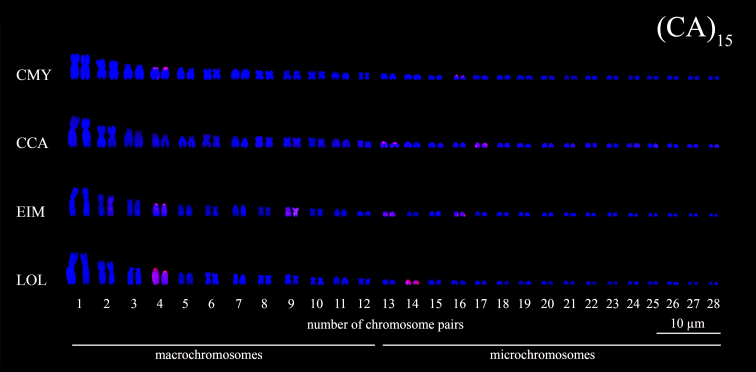

Microsatellites: distribution pattern

Distinct microsatellites signals were detected on chromosomes of C. mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea (Figures 4-7). The (GAA)10, (CGC)10 and (GACA)8 microsatellites probes were not detected on the chromosomes of these four species by FISH procedure. The microsatellite (CA)n was located as a block in the short arms of the chromosome pairs 4 and 16 in C. mydas (Figures 2 and 4). Caretta caretta has (CA)n block detected in mc 13 and dispersed in mc 17 (Figures 2 and 4). In E. imbricata, (CA)n signals were visualized as a block in chromosome pairs 2, 4, 13 and 16, and dispersed along chromosome pair 9 (Figures 2 and 4). Lepidochelys olivacea has (CA)n markers detected as a block in the short arms of the acrocentric pair 4, besides dispersed signals along the chromosome pairs 4 and 14 (Figures 2 and 4).

Figure 4 - . Karyotypes of sea turtle species subjected to FISH using (CA)15 microsatellites probes (red signals). The species names were referred by their 3-letter acronym: C. mydas (CMY), C. caretta (CCA), E. imbricata (EIM) and L. olivacea (LOL).

(GA)n signals were detected in the mc pair 14 of C. mydas, in the mc pairs 13 and 14 of C. caretta, in the mc pairs 24 and 25 in E. imbricata, and in the mc 14 of L. olivacea (Figures 2 and 5). The microsatellite (CAG)n was located as block in chromosome pairs 13, 15-17 of C. mydas, besides dispersed signals along chromosome pairs 4, 5, 14, 19 and 21 (Figures 2 and 6). (CAG)n motifs were not detected in C. caretta karyotype (Figure 6), while in E. imbricata (CAG)n signals were located dispersed along the chromosome pairs 8, 13, 17 and 22 (Figures 2 and 6). In L. olivacea, (CAG)n signals were detected in the mc 13, 16, 17 and 19 (Figures 2 and 6). (GATA)n motifs were in situ located in the mc pairs 13, 15, 16 and 22 in C. mydas karyotype, in the mc pairs 13 and 16 in C. caretta, in the chromosome pairs 9, 16, 18, 19 and 24 in E. imbricata and, in the mc pairs 13 and 15 of the L. olivacea (Figures 2 and 7).

Figure 5 - . Karyotypes of sea turtle species subjected to FISH using (GA)15 microsatellites probes (red signals). The species names were referred by their 3-letter acronym: C. mydas (CMY), C. caretta (CCA), E. imbricata (EIM) and L. olivacea (LOL).

Figure 6 - . Karyotypes of sea turtle species subjected to FISH using (CAG)10 microsatellites probes (red signals). The species names were referred by their 3-letter acronym: C. mydas (CMY), C. caretta (CCA), E. imbricata (EIM) and L. olivacea (LOL).

Discussion

Sea turtles have been studied from a cytogenetic point of view (Bickham et al., 1980; Bickham and Carr, 1983; López et al., 2008; Fukuda et al., 2014), but the lack of comparative karyotype studies prevents a more robust analysis of evolutionary chromosomal changes. The first comparative cytogenetic study in sea turtles was conducted by Machado et al. (2020) based on G-banding and in situ location of 18S rDNA and telomere sequences. The compared karyotypes revealed species-specific chromosomal morphology involving macrochromosomes pairs 4, 5, 7, and 12 among C. mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea (Machado et al., 2020) and ruled out the proposal of identical karyotypes for sea turtles. Additionally, the same four Cheloniidae sea turtles that inhabiting the Brazilian coast were here investigated and showed chromosomal differences in heterochromatin and microsatellites distribution on the karyotypes, making possible to infer new molecular mechanisms in sea turtle diversification.

The heterochromatic blocks found in macrochromosomes varied among species and demonstrated an unusual feature which only one member of the homologous bears pericentromeric heterochromatic block for macrochromosome pairs 1, 2, and 3 in some species, as also detected by Bickham et al. (1980) in C. mydas. It’s known that satellite DNA (including micro- and minisatellites) is made up of systematic in tandem repeats favoring the occurrence of ectopic recombination and genic conversion (Schweizer and Loidl, 1987; Louzada et al., 2020), which could led to a differential in cis accumulation of satellite DNA units on heterochromatin blocks, as visualized in sea turtles’ chromosomes. In other pathway, homologous recombination involving transposable elements surrounding pericentromeric region could promote substantial differences in heterochromatin block sizes (Xiao and Peterson, 2000).

Phylogenetic analyses proposed that Dermochelyidae and Cheloniidae diverged from Americhelydia ancestral lineage in the Cretaceous and that all Cheloniidae species diverged from Dermochelys coriacea (Iverson et al., 2007; Naro-Maciel et al., 2008; Valenzuela and Adams, 2011; Montiel et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2017). In addition, an ancestral reconstruction demonstrated that the Chelonini tribe (C. mydas and N. depressus) split from Carettini about 34 million years ago (Mya), and in Carettini, Eretmochelys split from Caretta and Lepidochelys about 23 Mya (see Figure 1; Pereira et al., 2017). Interestingly, the distinct chromosome pairs morphologies observed among C. mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea, proposed by Machado et al. (2020), also had diverged in pericentromeric heterochromatin composition, mainly in the pairs 4 and 12.

Different chromosome morphologies (considering the centromere position) in a homeologue chromosome pair among phylogenetically related species may be the result of chromosomal rearrangements (Charlesworth et al., 1994). However, some studies suggested that the repositioning of the centromere can occur, without changes of the DNA markers along the chromosomes (Montefalcone et al., 1999; Ventura et al., 2001). The repositioning of the centromere occurs because of the emergence of a new centromere due to numerous epigenetic changes and not by relocating an existing centromere from another genomic site (Amor et al., 2004). Thus, since G-banding technique did not evidence the occurrence of pericentric inversions among sea turtle chromosomes (Machado et al., 2020), the presence vs. absence or differences in the centromeric heterochromatin content reinforce the proposal of centromeric repositioning mechanism occurrence in the diversification of some chromosomes among C. mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea.

Changes in pericentromeric heterochromatin composition among sea turtles’ chromosomes, as partially demonstrated by microsatellites in situ localization and C-banding, could have emerged to new centromeres and could have led to morphological chromosome alterations. Applying the evolutionary scenario proposed by molecular phylogenetic studies (Iverson et al., 2007; Naro-Maciel et al., 2008; Valenzuela and Adams, 2011; Montiel et al., 2016, Pereira et al., 2017), the bi-armed chromosome pairs 4 and 5 from C. mydas could have diverged to acrocentric in E. imbricata and L. olivacea (Figure 1). Contrary to phylogenetic data that infers C. caretta diverged from E. imbricata, C. caretta shared chromosome pairs 4 and 5 morphology with C. mydas, probably indicating chromosomal homoplasy. In addition, C. caretta is the only turtle, among the four species studied, that have chromosome pair 7 bi-armed, indicating specific chromosomal changes in the evolutionary lineage that still need to be solved.

Following the phylogenetic proposal, the acrocentric pair 12 of E. imbricata diverged from a metacentric one present in C. mydas, since the location of a conspicuous heterochromatic block is shared between these chromosomes and G-banding recovered its probable homeology (Machado et al., 2020). The proposal by Machado et al. (2020) of partial deletion or translocation in the origin of the chromosome pair 12 in E. imbricata is corroborated in the present data once no chromosomal inversion or DNA repeat unit’s retraction has been detected. In this way, the chromosomal rearrangement should be a recent and specific event occurred in E. imbricata, once C. caretta and L. olivacea shared the metacentric pair 12 with C. mydas (Figure 1).

Usually, microsatellites accumulations were demonstrated in the terminal regions of vertebrate chromosomes, which seems to be a common feature due to different mechanisms that accumulate these sequences in these regions (Pokorná et al., 2011b; Torres et al., 2011; Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015; Ernetti et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019; Viana et al., 2020). The (CA)n, (GA)n, (CAG)n and (GATA)n microsatellites were reported for the first time in sea turtle’s karyotypes and demonstrated that most of them possibly make up part of the repetitive units of heterochromatin in C. mydas, C. caretta, L. olivacea and E. imbricata, especially in mc. Furthermore, the chromosomal location of microsatellites sequences in the pericentromeric regions for some chromosomes is common in species groups close to turtles, such as birds and crocodilians (Rao et al., 2010; Nishida et al., 2013; Matsubara et al., 2016; de Oliveira et al., 2017; Kretschmer et al., 2018; Barcellos et al., 2019). In this study, only the (CA)15 repetition was observed in pericentromeric region for the macrochromosome pair 4 of C. mydas, E. imbricata and L. olivacea, which reinforces the hypothesis of a probable homeology among the pairs and that the morphological differences observed among the chromosomes are the result of a possible centromeric repositioning (Machado et al., 2020).

The microsatellite (GA)n showed accumulated signals in the Nucleolus Organizer Region (NOR) locus, except for E. imbricata. Studies have shown that the frequent association between microsatellites and NOR regions is explained by large number of microsatellites in rDNA intergenic spacers (Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015; Agrawal and Ganley, 2018). Furthermore, the fact that these microsatellites could be found in blocks, dispersed or absents along the chromosome arms may reflect a possible trend of expansion of these microsatellites in the genomes (Pokorná et al., 2011b; Ruiz-Ruano et al., 2015). Dispersed distributions of microsatellite on chromosomes are constantly associated with TEs, which can contribute to the dispersion of these sequences in the genome (Pucci et al., 2016).

The absence of (CAG)n signals in the chromosomes of C. caretta demonstrated that this repetition may have contracted (deletion of repetitive units) in the genome (López-Flores and Garrido-Ramos, 2012) to a reduced number of copies, undetectable by FISH procedure (Kretschmer et al., 2018). The number of heterochromatic bands and microsatellites (CA)n, (GA)n and (GATA)n sites also were lower in C. caretta when compared to C. mydas, E. imbricata and L. olivacea, corroborating that C. caretta has a probable divergent karyotype evolution from the other Carettini species.

(GATA)n sequence can be found in the promoter region of the Doublesex and mab-3-related transcription factor 1 (Dmrt1) gene (Raymond et al., 2000). Dmrt1 is a gene that acts during sex determination stages in reptile development (Kettlewell et al., 2000; Mizoguchi and Valenzuela, 2020), in which the sex of the embryos is determined by the incubation temperature of the nest (temperature-dependent sex determination: TSD), the most common mechanism of environmental sex determination (ESD) (Ferreira Júnior, 2009). Although, genotypic sex determination was described to have evolved independently in five families of turtles (Chelidae, Emydidae, Geoemydidae, Kinosternidae and Trionychidae) (Valenzuela and Adams, 2011, Valenzuela et al., 2014; Badenhorst et al., 2013; Rovatsos et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019; Viana et al., 2020), sea turtles were described as belonging to a TSD lineage (Bickham et al., 1980; Morreale et al., 1982; Yntema and Mrosovsky, 1982; Mrosovsky et al., 1984, 1992; Valenzuela and Adams, 2011; Montiel et al., 2016). Previous in situ localization of (GATA)n in three species of turtles with TSD, using both sexes, detected markers preferably in mc and without evidence of sex-specific chromosomal sites (Mazzoleni et al., 2019). In situ location of (GATA)n in C. mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea showed accumulations in mc pairs, in addition to a macrochromosome in E. imbricata. However, the absence of size heteromorphism between homeologous chromosomes carrying (GATA)n sites reinforces the condition of the absence of heteromorphic sex chromosomes in this group.

In conclusion, this study corroborates the proposal of the centromere repositioning to explain chromosomal morphology alterations in sea turtle diversification, addressing important concerns to absence of pericentromeric heterochromatin in macrochromosomes of Carettini, especially in C. caretta. Furthermore, heterochromatic bands and microsatellite sites showed chromosomal differences among C. mydas, C. caretta, E. imbricata and L. olivacea karyotypes. These findings encourage further research on the chromosomal evolution in sea turtle species aiming to understand the diversification of Cheloniidae karyotypes.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Projeto TAMAR/Fundação Pro-Tamar; Aquário Natal; Laboratório de Ecologia e Conservação (LEC) and Laboratório de Citogenética Evolutiva e Conservação (CECA) of the Universidade Federal do Paraná; Centro de Tecnologias Avançadas em Fluorescência (CETAF/UFPR), and; Associação MarBrasil for all support provided. CRDM and LG would like to thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior Brasil (CAPES/PROAP - Financial Code 001) for the postgraduate scholarship.

Supplementary material.

The following online material is available for this article:

References

- Agrawal S, Ganley ARD. The conservation landscape of the human ribosomal RNA gene repeats. PloS One. 2018;13:e0207531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amavet P, Markariani R, Fenocchio A. Comparative cytogenetic analysis of the South American alligators Caiman latirostris and Caiman yacare (Reptilia, Alligatoridae) from Argentina. Caryologia. 2003;56:489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Amor DJ, Bentley K, Ryan J, Perry J, Wong L, Slater H, Choo KA. Human centromere repositioning “in progress”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6542–6547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308637101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arantes LS, Vilaça ST, Mazzoni CJ, Santos FR. New genetic insights about hybridization and population structure of hawksbill and loggerhead turtles from Brazil. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.17.046623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres M, Sampaio MM, Barros RMS, Dias LB, Cunha OR. A karyological study of turtles from the Brazilian Amazon region. Cytogenet Genome Res. 1969;8:401–409. doi: 10.1159/000130051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenhorst D, Stanyon R, Engstrom T, Valenzuela N. A ZZ/ZW microchromosome system in the spiny softshell turtle, Apalone spinifera, reveals an intriguing sex chromosome conservation in Trionychidae. Chromosome Res. 2013;21:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s10577-013-9343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos SA, Kretschmer R, de Souza MS, Costa AL, Degrandi TM, dos Santos MS, de Oliveira EHC, Cioffi MB, Gunski RJ, Garnero ADV. Karyotype evolution and distinct evolutionary history of the W chromosomes in swallows (Aves, Passeriformes) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2019;158:98–105. doi: 10.1159/000500621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros RM, Sampaio MM, Assis MF, Ayres M. General considerations on the karyotypic evolution of Chelonia from the Amazon region of Brazil. Cytologia. 1976;41:559–565. [Google Scholar]

- Bickham JW, Bjorndal KA, Haiduk MW, Rainey WE. The karyotype and chromosomal banding patterns of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) Copeia. 1980;1980:540–543. [Google Scholar]

- Bickham JW, Carr JL. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the higher categories of cryptodiran turtles based on a cladistic analysis of chromosomal data. Copeia. 1983;1983:918–932. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen BW, Karl SA. Population genetics, phylogeography, and molecular evolution. In: Lutz PL, Musick JA, editors. The Biology of Sea Turtles. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1996. pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante MG, Bastos CEMC, Nagamachi CY, Pieczarka JC, Vicari MR, Noronha RCR. Physical mapping of repetitive DNA suggests 2n reduction in Amazon turtles Podocnemis (Testudines: Podocnemididae) PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante MG, Nagamachi CY, Pieczarka JC, Noronha RCR. Evolutionary insights in Amazonian turtles (Testudines, Podocnemididae): co-location of 5S rDNA and U2 snRNA and wide distribution of Tc1/Mariner. Biol Open. 2020;9:bio049817. doi: 10.1242/bio.049817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante MG, Souza LF, Vicari MR, de Bastos CEM, de Sousa JV, Nagamachi Y, Pieczarka C, Martins C, Noronha RCR. Molecular cytogenetics characterization of Rhinoclemmys punctularia (Testudines, Geoemydidae) and description of a Gypsy-H3 association in its genome. Gene. 2020;738:e144477. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Sniegowski P, Stephan W. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature. 1994;371:215–220. doi: 10.1038/371215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente L, Mazzoleni S, Bellavia EP, Augstenová B, Auer M, Praschag P, Protiva T, Velenský P, Wagner P, Fritz U, et al. Interstitial telomeric repeats are rare in turtles. Genes. 2020;11:657. doi: 10.3390/genes11060657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin JE, Ezaz T. Understanding the Evolution of reptile chromosomes through application of combined cytohenetic and genomic approaches. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2019;157:7–20. doi: 10.1159/000495974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira TD, Kretschmer R, Bertocchi NA, Degrandi TM, de Oliveira EHC, Cioffi MB, Garnero ADV, Gunski RJ. Genomic organization of repetitive DNA in woodpeckers (Aves, Piciformes): Implications for karyotype and ZW sex chromosome differentiation. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton PH, Davis SK, Guerra T, Owens D. Molecular phylogeny for marine turtles based on sequences of the ND4-leucine tRNA and control regions of mitochondrial DNA. Mol Phyl Evol. 1996;5:511–521. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernetti JR, Gazolla CB, Recco-Pimentel SM, Luca EM, Bruschi DP. Non-random distribution of microsatellite motifs and (TTAGGG) n repeats in the monkey frog Pithecopus rusticus (Anura, Phyllomedusidae) karyotype. Genet Mol Biol. 2019;42:e20190151. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2019-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira PD., Júnior Aspectos ecológicos da determinação sexual em tartarugas. Acta Amazon. 2009;39:139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Katayama M, Kinoshita K, Kasugai T, Okamoto H, Kobayashi K, Kurita M, Soichi M, Donai K, Uchida T, et al. Primary fibroblast cultures and karyotype analysis for the olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2014;50:381–383. doi: 10.1007/s11626-013-9715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Ramos MA. Satellite DNA in plants: more than just rubbish. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2015;146:153–170. doi: 10.1159/000437008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannucci A, Svartman M, Bellavita M, Chelazzi G, Stanyon R, Ciofi C. Insights into emydid turtle cytogenetics: the European pond turtle as a model species. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2019;157:166–171. doi: 10.1159/000495833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson JB, Brown RM, Akre TS, Near TJ, Le M, Thomson RC, Starkey DE. In search of the tree of life for turtles. Chel Res Monogr. 2007;4:85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoshi T, Nishida C, Ota H, Kumazawa Y, Endo H, Matsuda Y. Molecular structures of centromeric heterochromatin and karyotypic evolution in the Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis) (Crocodylidae, Crocodylia) Chromosome Res. 2008;16:1119–1132. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-1263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettlewell JR, Raymond CS, Zarkower D. Temperature‐dependent expression of turtle Dmrt1 prior to sexual differentiation. Genesis. 2000;26:174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer R, de Oliveira TD, de Oliveira IF, Silva FAO, Gunski RJ, Garnero ADV, Cioffi MB, Oliveira EHCD, Freitas TROD. Repetitive DNAs and shrink genomes: A chromosomal analysis in nine Columbidae species (Aves, Columbiformes) Genet Mol Biol. 2018;41:98–106. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2017-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubat Z, Hobza R, Vyskot B, Kejnovsky E. Microsatellite accumulation on the Y chromosome in Silene latifolia. Genome. 2008;51:350–356. doi: 10.1139/G08-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Ruiz P, Lopez GG, Santos FR, Soares LS. Extensive hybridization in hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) nesting in Brazil revealed by mtDNA analyses. Conserv Genet. 2006;7:773–781. [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Montiel EE, Navarro-Domínguez BM, Valenzuela N. Chromosomal rearrangements during turtle evolution altered the synteny of genes involved invertebrate sex determination. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2019;157:77–88. doi: 10.1159/000497302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López AE, Hernández-Fernández J, Bernal-Villegas J. Condiciones óptimas de cultivo de linfocitos y análisis parcial del cariotipo de la tortuga cabezona, Caretta caretta (Testudines: Cheloniidae) en Santa Marta, Caribe Colombiano. Rev Biol Trop. 2008;56:1459–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Flores I, Garrido-Ramos MA. The repetitive DNA content of eukaryotic genomes. In: Garrido-Ramos MA, editor. Repetitive DNA. Vol. 7. Karger Publishers; Basel: 2012. pp. 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louzada S, Lopes M, Ferreira D, Adega F, Escudeiro A, Gama-Carvalho M, Chaves R. Decoding the role of satellite DNA in genomic architecture and plasticity - an evolutionary and clinical affair. Genes. 2020;11:72. doi: 10.3390/genes11010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado CRD, Glugoski L, Domit C, Pucci MB, Goldberg DW, Marinho LA, Costa GWWF, Nogaroto V, Vicari MR. Comparative cytogenetics of four sea turtle species (Cheloniidae): G-banding pattern and in situ localization of repetitive DNA units. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2020 doi: 10.1159/000511118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K, O’Meally D, Azad B, Georges A, Sarre SD, Graves JAM, Matsuda Y, Ezaz T. Amplification of microsatellite repeat motifs is associated with the evolutionary differentiation and heterochromatinization of sex chromosomes in Sauropsida. Chromosoma. 2016;125:111–123. doi: 10.1007/s00412-015-0531-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni S, Augstenová B, Clemente L, Auer M, Fritz U, Praschag P, Protiva T, Velenský P, Kratochvíl L, Rovatsos M. Turtles of the genera Geoemyda and Pangshura (Testudines: Geoemydidae) lack differentiated sex chromosomes: the end of a 40-year error cascade for Pangshura. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6241. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi B, Valenzuela N. Alternative splicing and thermosensitive expression of Dmrt1 during urogenital development in the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta. PeerJ. 2020;8:e8639. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montefalcone G, Tempesta S, Rocchi M, Archidiacono N. Centromere repositioning. Genome Res. 1999;9:1184–1188. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.12.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montiel EE, Badenhorst D, Lee LS, Literman R, Trifonov V, Valenzuela N. Cytogenetic insights into the evolution of chromosomes and sex determination reveal striking homology of turtle sex chromosomes to amphibian autosomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;148:292–304. doi: 10.1159/000447478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morreale SJ, Ruiz GJ, Standor EA. Temperature-dependent sex determination: current practices threaten conservation of sea turtles. Science. 1982;216:1245–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.7079758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrosovsky N, Dutton PH, Whitmore CP. Sex ratios of two species of sea turtle nesting in Suriname. Can J Zool 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Mrosovsky N, Bass A, Corliss LA, Richardson JI, Richardson TH. Pivotal and beach temperatures for hawksbill turtles nesting in Antigua. Can J Zool. 1992;70:1920–1925. [Google Scholar]

- Naro-Maciel E, Le M, FitzSimmon NN, Amato G. Evolutionary relationships of marine turtles: a molecular phylogeny based on nuclear and mitochondrial genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;49:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida C, Ishijima J, Ishishita S, Yamada K, Griffin DK, Yamazaki T, Matsuda Y. Karyotype reorganization with conserved genomic compartmentalization in dot-shaped microchromosomes in the Japanese mountain hawk-eagle (Nisaetus nipalensis orientalis, Accipitridae) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2013;141:284–294. doi: 10.1159/000352067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noleto RB, Kantek DLZ, Swarça AC, Dias AL, Fenocchio AS, Cestari MM. Karyotypic characterization of Hydromedusa tectifera (Testudines, Pleurodira) from the upper Iguaçu River in the Brazilian state of Paraná. Genet Mol Biol. 2006;29:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Noronha RCR, Barros LMR, Araújo REF, Marques DF, Nagamachi CY, Martins C, Pieczarka JC. New insights of karyoevolution in the Amazonian turtles Podocnemis expansa and Podocnemis unifilis (Testudines, Podocnemidae) Mol Cytogenet. 2016;9:73. doi: 10.1186/s13039-016-0281-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmo E. Trends in the evolution of reptilian chromosomes. Integr Comp Biol. 2008;48:4. doi: 10.1093/icb/icn049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham JF, Fastovsky DE. The phylogeny of cheloniid marine turtles revisited. Chel Cons Biol. 1997;2:548–554. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AG, Sterli J, Moreira FR, Schrago CG. Multilocus phylogeny and statistical biogeography clarify the evolutionary history of major lineages of turtles. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;113:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorná M, Giovannotti M, Kratochvíl L, Kasai F, Trifonov VA, O’Brien PC, Caputo V, Olmo E, Ferguson-Smith MA, et al. Strong conservation of the bird Z chromosome in reptilian genomes is revealed by comparative painting despite 275 million years divergence. Chromosoma. 2011;120:455. doi: 10.1007/s00412-011-0322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorná M, Kratochvíl L, Kejnovský E. Microsatellite distribution on sex chromosomes at different stages of heteromorphism and heterochromatinization in two lizard species (Squamata: Eublepharidae: Coleonyx elegans and Lacertidae: Eremias velox) BMC Genet. 2011;12:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-12-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard PCH. Evolution, phylogeny and current status. In: Lutz PL, Musick JA, editors. The Biology of Sea Turtles. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1997. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Proietti MC, Reisser J, Marins LF, Marcovaldi MA, Soares LS, Monteiro DS, Wijeratne S, Pattiaratchi C, Secchi ER. Hawksbill × loggerhead sea turtle hybrids at Bahia, Brazil: where do their offspring go? PeerJ. 2014;2:e255. doi: 10.7717/peerj.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucci MB, Barbosa P, Nogaroto V, Almeida MC, Artoni RF, Scacchetti PC, Pansonato-Alves JC, Foresti F, Moreira-Filho O, Vicari MR. Chromosoma l spreading of microsatellites and (TTAGGG)n sequences in the Characidium zebra and C. gomesi genomes (Characiformes: Crenuchidae) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;149:182–190. doi: 10.1159/000447959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SR, Trivedi S, Emmanuel D, Merita K, Hynniewta M. DNA repetitive sequences-types, distribution and function: a review. J Cell Mol Biol. 2010;7:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CS, Murphy MW, O'Sullivan MG, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. Dmrt1, a gene related to worm and fly sexual regulators, is required for mammalian testis differentiation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2587–2595. doi: 10.1101/gad.834100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez PA, Ortiz ML, Bueno ML. Agentes mitogénicos para cultivos de linfocitos en quelonios. Orinoquia. 2003;7:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rovatsos M, Praschag P, Fritz U, Kratochvšl L. Stable Cretaceous sex chromosomes enable molecular sexing in softshell turtles (Testudines: Trionychidae) Sci Rep. 2017;7:42150. doi: 10.1038/srep42150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ruano FJ, Cuadrado Á, Montiel EE, Camacho JPM, López-León MD. Next generation sequencing and FISH reveal uneven and nonrandom microsatellite distribution in two grasshopper genomes. Chromosoma. 2015;124:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s00412-014-0492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemberger MO, Nascimento VD, Coan R, Ramos É, Nogaroto V, Ziemniczak K, Valente GT, Moreira-Filho O, Martins C, Vicari MR. DNA transposon invasion and microsatellite accumulation guide W chromosome differentiation in a Neotropical fish genome. Chromosoma. 2019;128:547–560. doi: 10.1007/s00412-019-00721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer D, Loidl J. A model for heterochromatin dispersion and the evolution of C-band patterns. Chromosomes Today. 1987;9:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sites JJW, Bickham JW, Haiduk MW, Iverson JB. Banded karyotypes of six taxa of kinosternid turtles. Copeia. 1979;1979:692–698. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner AT. A simple technique for demonstrating centromeric heterochromatin. Exp Cell Res. 1972;75:304–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner AT. Chromosomes organization and function. Blackwell Science Ltd.; North Berwick: 2003. pp. 294–294. [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D. Notes on the definition and nomenclature of tandemly repetitive DNA sequences. In: Pena SD, editor. DNA fingerprinting: State of the science. Birkhäuser; Basel: 1993. pp. 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GA, Gong Z, Iovene M, Hirsch CD, Buell CR, Bryan GJ, Novák P, Jiří M, Jiang J. Organization and evolution of subtelomeric satellite repeats in the potato genome. G3: Genes Genom Genet. 2011;1:85–92. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth G, Gáspári Z, Jurka J. Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Res. 2000;10:967–981. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela N, Adams DC. Chromosome number and sex determination co-evolve in turtles. Evolution. 2011;65:1808–1813. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela N, Badenhorst D, Montiel EE, Literman R. Molecular cytogenetic search for cryptic sex chromosomes in painted turtles Chrysemys picta. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2014;144:39–46. doi: 10.1159/000366076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura M, Archidiacono N, Rocchi M. Centromere emergence in evolution. Genome Res. 2001;11:595–599. doi: 10.1101/gr.152101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana PF, Feldberg E, Cioffi MB, de Carvalho VT, Menezes S, Vogt RC, Liehr T, Ezaz T. The Amazonian Red Side-Necked Turtle Rhinemys rufipes (Spix, 1824) (Testudines, Chelidae) has a GSD sex determining mechansm with an ancient XY sex microchromosome system. Cells. 2020;9:2088. doi: 10.3390/cells9092088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YL, Peterson T. Intrachromosomal homologous recombination in Arabidopsis induced by a maize transposon. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;263:22–29. doi: 10.1007/pl00008672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yntema CL, Mrosovsky N. Critical periods and pivotal temperatures for sexual differentiation in loggerhead sea turtles. Can J Zool. 1982;60:1012–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Zattera ML, Gazolla CB, Soares ADA, Gazoni T, Pollet N, Recco-Pimentel SM, Bruschi DP. Evolutionary dynamics of the repetitive DNA in the karyotypes of Pipa carvalhoi and Xenopus tropicalis (Anura, Pipidae) Front Genet. 2020;11:637. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemniczak K, Traldi JB, Nogaroto V, Almeida MC, Artoni RF, Moreira-Filho O, Vicari MR. In situ localization of (GATA)n and (TTAGGG)n repeated DNAs and W sex chromosome differentiation in Parodontidae (Actinopterygii: Characiformes) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2014;144:325–332. doi: 10.1159/000370297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- IUCN The IUCN red list of threatened species. 2020. [March 19, 2020]. https://www.iucnredlist.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.