Abstract

Objective

To determine whether a fraction of patients with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) had been cured by systemic and intraventricular methotrexate- and cytarabine-based chemotherapy (Bonn protocol) after a very long-term follow-up of nearly 20 years.

Methods

Sixty-five patients (median age 62 years, range 27–75; median Karnofsky performance score 70, range 20–90) had been treated with systemic and intraventricular polychemotherapy without whole brain radiotherapy from September 1995 until December 2001. All patients still alive in 2019 were contacted and interviewed on their current life situation.

Results

Median follow-up for surviving patients was 19.6 years (17.5–23.3 years). Out of 65 patients, 11 (17%) were still alive. Six of those never experienced any relapse. For the whole study population, median overall survival (OS) was 4.4 years (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.9–5.9); for patients ≤60 years, 11.0 years (95% CI 4.8–17.0). The 10-year OS rate for the entire cohort was 29% and the estimated 20-year OS rate was 19%. Four late relapses were observed after 9.8, 10.3, 13.3, and 21.0 years.

Conclusion

At a median follow-up of 19.6 years, 17% of patients were alive and free of tumor; however, even after response for decades, an inherent risk of relapse, either systemic or cerebral, characterizes the biology of PCNSL.

Classification of evidence

This work provides Class III evidence that PCNSL treatment with methotrexate-based polychemotherapy including intraventricular therapy is associated with long-term disease control in some patients.

Primary CNS lymphomas (PCNSLs) are highly aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with a worse prognosis than their systemic counterparts.1 In the past 2 decades, treatment developments in PCNSL focused on establishing effective radiation-free2–7 or reduced dose radiation8 protocols to avoid late cognitive decline after whole brain radiotherapy.9–13 For most of these trials, no long-term data are available. There is one study with a follow-up period of up to 23 years on 149 patients with PCNSL treated with intraarterial methotrexate after osmotic blood–brain barrier disruption (BBBD) that reported a median overall survival (OS) of 3.1 years, a 5-year OS rate of 41%, and an 8.5-year OS rate of 25%.7

The Bonn protocol was one of the first radiation-free protocols. It produced promising results that had been reported on in 2003 and 2010.14,15 In a multicenter pilot/phase II trial, 65 patients had been treated with high-dose methotrexate- and cytarabine-based systemic therapy in combination with intraventricular methotrexate, prednisolone, and Ara-C. Durable responses in a high fraction of patients were observed (median OS 54 months) without neurocognitive decline at long-term follow-up.15 For patients ≤60 years, median OS had not yet been reached after a median follow-up of 100 months with a survival rate at 100 months of 57%.15 According to these results, we concluded that the Bonn protocol might be curative for PCNSL in a fraction of patients, particularly in younger patients. We carried out this very long-term follow-up to further substantiate this assumption.

Methods

Study procedures

Between September 1995 and December 2001, 65 patients had been enrolled in an multicenter pilot/phase II study evaluating a treatment protocol (Bonn protocol) including systemic and intraventricular therapy for PCNSL.14 Treatment consisted of systemic chemotherapy with 6 cycles of high-dose methotrexate (3–5 g/m2, cycles 1, 2, 4, and 5) and Ara-C (3 g/m2/d days 1–2, cycles 3 and 6) combined with vinca-alkaloids, ifosfamide, and cyclophosphamide. In addition, methotrexate, prednisolone, and Ara-C were administered via Ommaya reservoir in each cycle. The details of treatment, toxicity, and response were reported previously,14 as was data concerning favorable neurocognitive outcome for surviving patients at a median follow-up of 100 months.15

Current information on actual survival and independence in daily living was collected by reviewing the archives of participating centers, by information received from treating general practitioners, by nonstandardized telephone interviews with patients themselves, or, if no information was available by the aforementioned methods, by a formal inquiry at the local registration office.

Statistical analysis

OS was calculated from the date of histologic diagnosis to death or last date of follow-up. Time to treatment failure (TTF) was defined as time from onset of treatment to disease progression or relapse, death from any cause, discontinuation of treatment because of any cause, or last date of follow-up. OS and TTF were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Log-rank tests were used to compare survival between patient groups. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. A competing risk of death analysis was done comparing disease-related death and death for other reasons.

Standard protocol approvals, registration, and patient consent

The ethics committees of the Faculties of Medicine of the Universities involved in treatment had approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The trial was conducted from 1995 to 2001 and had therefore not been registered by ClinicalTrials.gov.

Data availability

Anonymized data can be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Classification of evidence

This work provides Class III evidence that treatment of PCNSL with methotrexate-based polychemotherapy including intraventricular therapy is efficient and is associated with long-term disease control in a fraction of patients (after a median follow-up of 19.6 years, 17% of patients were alive).

Results

Patient characteristics

In March 2019, a total of 65 patients was evaluated. Median age of all patients was 62 years (range 27–75 years) at first diagnosis, 30 of 65 patients were 60 years or younger, and 34 patients were male. Median Karnofsky Performance Scale score (KPS) was 70 (range 20–90). Sixteen patients (25%) had a KPS of ≤50 at first diagnosis. One of 65 patients had ocular involvement at first diagnosis. Intraventricular therapy was applied in 64 patients; 1 patient refused intraventricular treatment. Median follow-up for surviving patients was 19.6 years (range 17.5–23.3 years). One patient was lost to follow-up 21 years after first diagnosis (while reportedly alive and free of relapse). For 8 patients (12%), the cause of death was unknown.

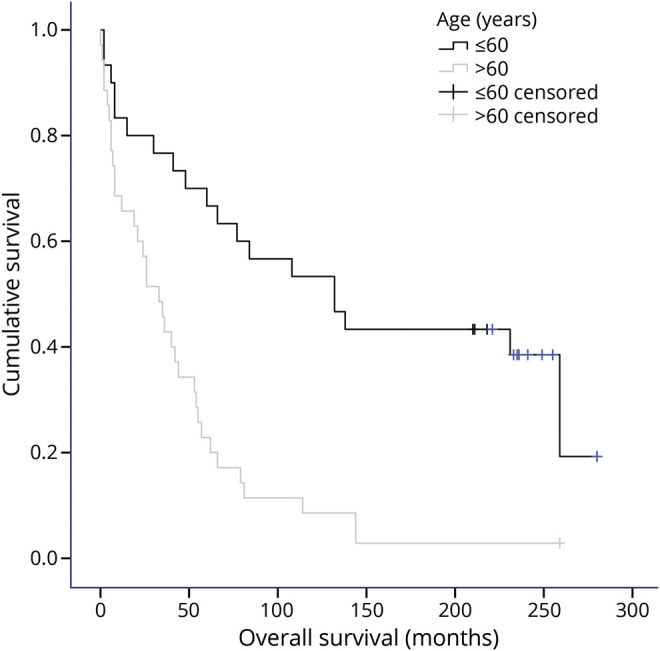

Survival analysis

Median OS for all patients was 53 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 35–71 months), 5-year OS 43%, 10-year OS 29%, and the Kaplan-Meier survival estimate at 20 years 19%. Median OS for patients ≤60 years was 11 years (132 months, 95% CI 57–204 months), and for patients >60 years, 33 months (95% CI 19–47 months, p < 0.001; figure). For patients ≤60 years, the 5-year OS was 70%, 10-year OS 53%, and the estimated 20-year OS 39%. For patients >60 years 5-year OS was 23%, 10-year OS 9%, and the estimated 20-year OS 3%. Median TTF was 21 months (95% CI 6–36 months) for all patients. Median TTF for patients ≤60 years was 41 months (95% CI 7–75 months), and for patients >60 years, 5 months (95% CI 0–18 months, p < 0.001).

Figure. Overall survival according to age.

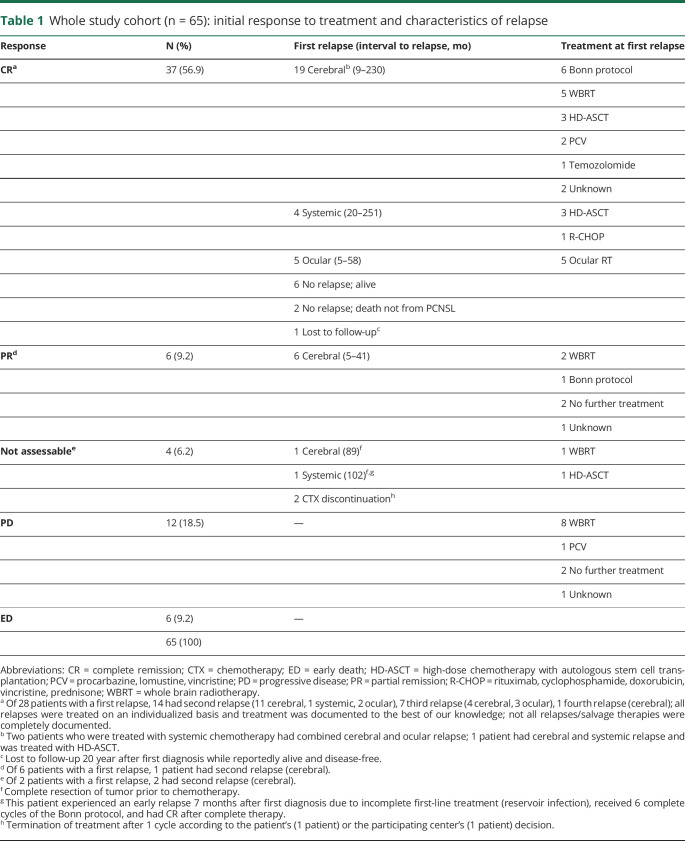

Initial response, response duration, and long-term survival

Of the entire cohort of 65 patients, 37 showed CR, 6 partial response (PR), 12 progressive disease, and 6 early death (ED) (table 1). Four responses were not assessable after complete resection of tumor (2 patients) or treatment termination after 1 cycle according to the patient's (1 patient) or the participating center's (1 patient) decision. One patient with PR was irradiated after incomplete chemotherapy as a result of nephrotoxicity, 1 patient with PR discontinued chemotherapy and received no further treatment, and the other 4 patients with PR showed only minimal residual lymphoma on MRI after completion of treatment and no further therapy was applied (complete response unconfirmed according to current criteria16).

Table 1.

Whole study cohort (n = 65): initial response to treatment and characteristics of relapse

Excluding patients with progressive disease and ED, in the remaining 47, a total of 36 documented first relapses occurred during follow-up (25 cerebral, 5 systemic, 1 systemic and cerebral, 5 ocular) after 5 months up to 251 months.

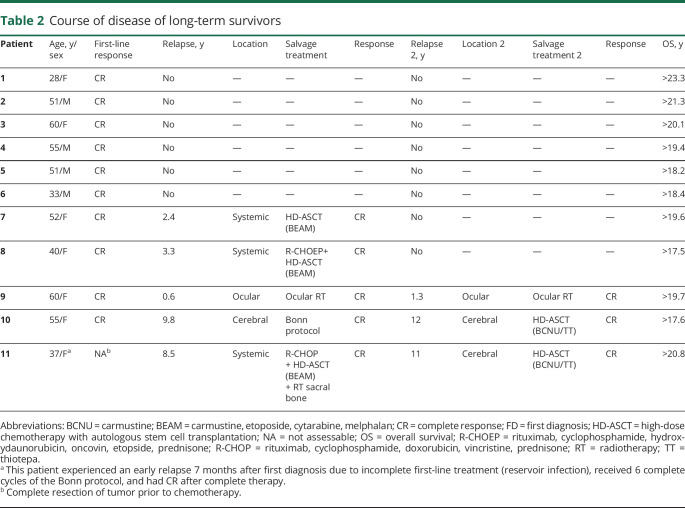

At follow-up in March 2019, 11 of 65 patients (17%) were still alive. Six of those never experienced a relapse. Five of 11 long-term survivors experienced first relapse (3 systemic, 1 cerebral, 1 ocular) after 7 up to 117 months and 3 patients also had second relapse (1 ocular, 2 cerebral) (table 2). Ten of 11 surviving patients were living at home at follow-up. One patient lived in a care facility after having had major cerebral ischemia. Three patients were still working. Five patients were retired but living independently at home (current age 72–80 years); 1 of these patients was the caregiver of his wife. For 2 patients, the current working status is unknown.

Table 2.

Course of disease of long-term survivors

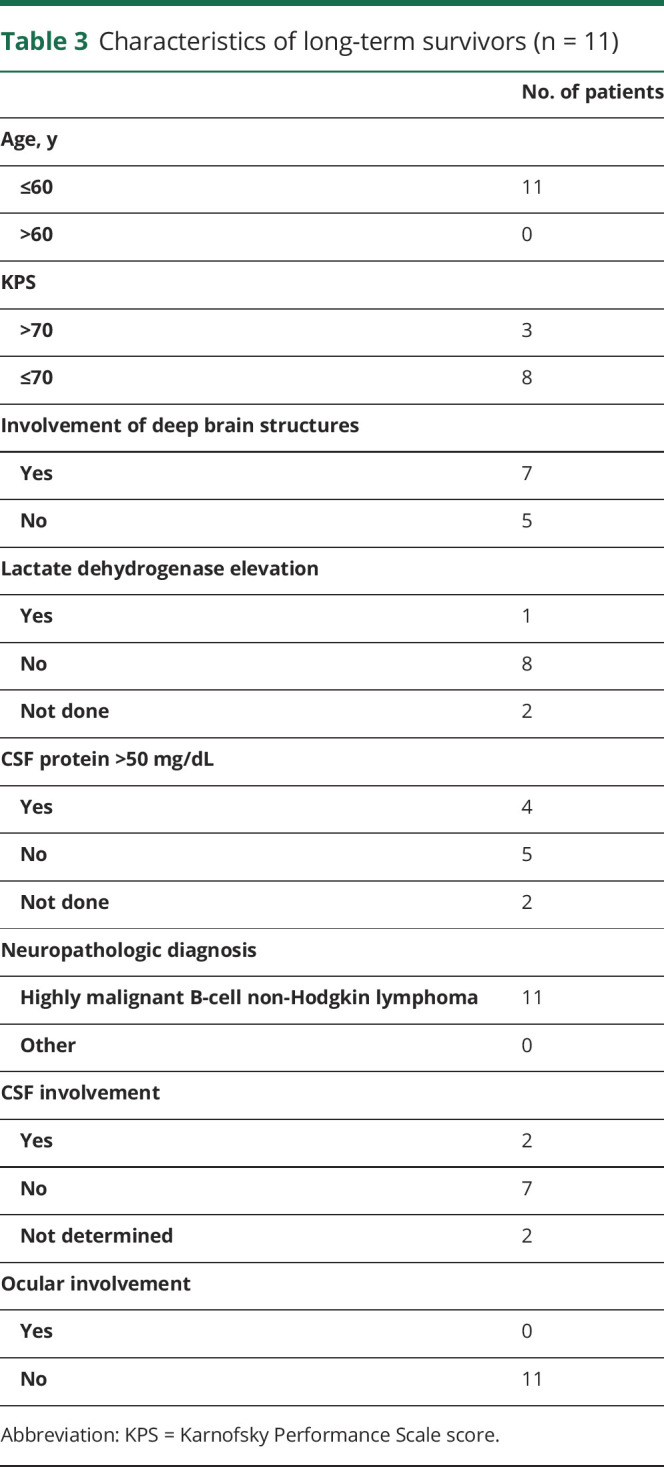

All long-term survivors were 60 years or younger at first diagnosis (range 28–60 years). Seven of 11 patients were female. Eight of 11 patients had a KPS of ≤70 and 1 of 11 had a KPS of ≤50 at first diagnosis. For 9 patients, the initial lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) serum value was available and 1 had elevated LDH at first diagnosis. For 9 patients, CSF sample data were available. Four of 9 patients had elevated protein (>50 mg/dL) in CSF and 2 of 9 patients had lymphoma cells in CSF cytology. In 7 of 11 patients, deep brain structures were involved by the tumor. None of the 11 patients had ocular involvement at first diagnosis. For details on patient characteristics of long-term survivors, see also table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of long-term survivors (n = 11)

Late relapses were observed in 4 patients after 9.8 (cerebral), 10.3 (systemic and cerebral), 13.3 (cerebral), and 21.0 (systemic) years (1 of these cases had already been published before17). Both patients with isolated cerebral relapses were treated with the Bonn protocol a second time, which again induced CR. The patient with systemic and cerebral relapse was treated with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) and died from treatment-related complications (sepsis). The patient with systemic relapse after 21.0 years was treated in another hospital unaware of the PCNSL diagnosis 21 years before. R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) was applied and the patient died from treatment-related complications (severe pneumonia).

Discussion

This analysis represents a very long-term follow-up of 65 patients with PCNSL, who had been treated within a pilot/phase II trial between 1995 and 2001. Results of the trial were published in 200314 and in 201015 with long-term disease control in about half of the younger patients (60 years and younger) after a median follow-up of 100 months.15 This very long-term follow-up after a median of 19.6 years for surviving patients shows that even after decades of complete response, relapses may occur. The possibility to compare our long-term data to those of other trials on chemotherapy alone,2 on chemotherapy with reduced dose radiation,8 or on HD-ASCT3–6 is limited, since these studies report on a median follow-up of 2.8–5.9 years. In our study, we observed very long-term survival in 12 patients (11 with documented follow-up and 1 lost to follow-up after 21 years when she was reportedly alive and disease free). Of the 11 patients with documented follow-up, 3 patients were still working, 5 patients were retired but living independently, 1 patient lived in a nursing facility after stroke, and for 2 patients the working status is unknown. No formal neuropsychological testing was done in this study for logistic reasons as patients were currently living in different places all over Germany. The 11 long-term survivors with documented follow-up were all 60 years or younger at first diagnosis; only the patient lost to follow-up with survival of more than 20 years was older than 60 years at diagnosis. Disregarding this single elderly patient, 6 of 11 long-term survivors never experienced relapse after a minimum of 18.2 years since first diagnosis. It is tempting to speculate that these 6 long-term survivors had actually been cured of PCNSL. However, we observed 4 late relapses after up to 21 years. This observation does not allow us to conclude that PCNSL can be considered cured after a definite time frame. Our results are in analogy to the results of a study on intraarterial methotrexate after osmotic BBBD in 149 patients, which also resulted in a small fraction of patients with long-term disease control with a follow-up period of up to 23 years (1982–2005, no range of follow-up was given). A median OS of 3.1 years was observed for all patients in this study: 5.2 years for patients <60 years of age and 2.2 years for patients ≥60 years. The 5-year OS rate was 41% and 8.5-year survival rate 25% for all patients. Patients <60 years had a 5-year OS rate of 52% and reportedly there was a plateau in the survival curve after 8.5 years. Relapses were observed also in this study after up to 9.7 years.7 These similar outcomes of 2 patient populations treated with different methotrexate-based protocols resulting in similar long-term results supports the hypothesis of an inherent risk of relapse in PCNSL due to the biology of the tumor itself rather than by the protocol applied. The question whether treatment protocols including HD-ASCT will lead to improved very long-term survival and to less risk of late relapse can only be answered when 20-year follow-up data on those trials3,5,6 will be available.

We cannot answer whether in late relapses the same B-cell clone is present as at first diagnosis, since none of our patients underwent biopsy at relapse. In a retrospective analysis on 378 patients with heterogenous first-line treatment, 10 patients relapsed after more than 5 years, with a median time to first relapse of 7.4 years (range 5.2–14.6). For 1 patient in this retrospective series, the persistence of the original PCNSL clone was histologically confirmed at cerebral relapse; for the other 2 patients for whom tissue was available, the investigation was uninformative.18 Other studies suggested that lymphoma cells in PCNSL at first diagnosis and at systemic or cerebral relapses have common precursor cells but also harbor unique somatic mutations.19,20

While durable responses with the Bonn protocol had been achieved with an estimated 20-year survival rate of 19%, the protocol had been criticized because of an Ommaya reservoir infection rate of 19%.14 We continue to use a modified version of the Bonn protocol at our clinic and by postponement of intraventricular therapy until the beginning of the fourth treatment cycle at the start of consolidation reduced Ommaya reservoir infection rates of 9% were achieved.21

Glossary

- BBBD

blood–brain barrier disruption

- CI

confidence interval

- ED

early death

- HD-ASCT

high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation

- KPS

Karnofsky Performance Scale

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- OS

overall survival

- PCNSL

primary CNS lymphoma

- PR

partial response

- TTF

time to treatment failure

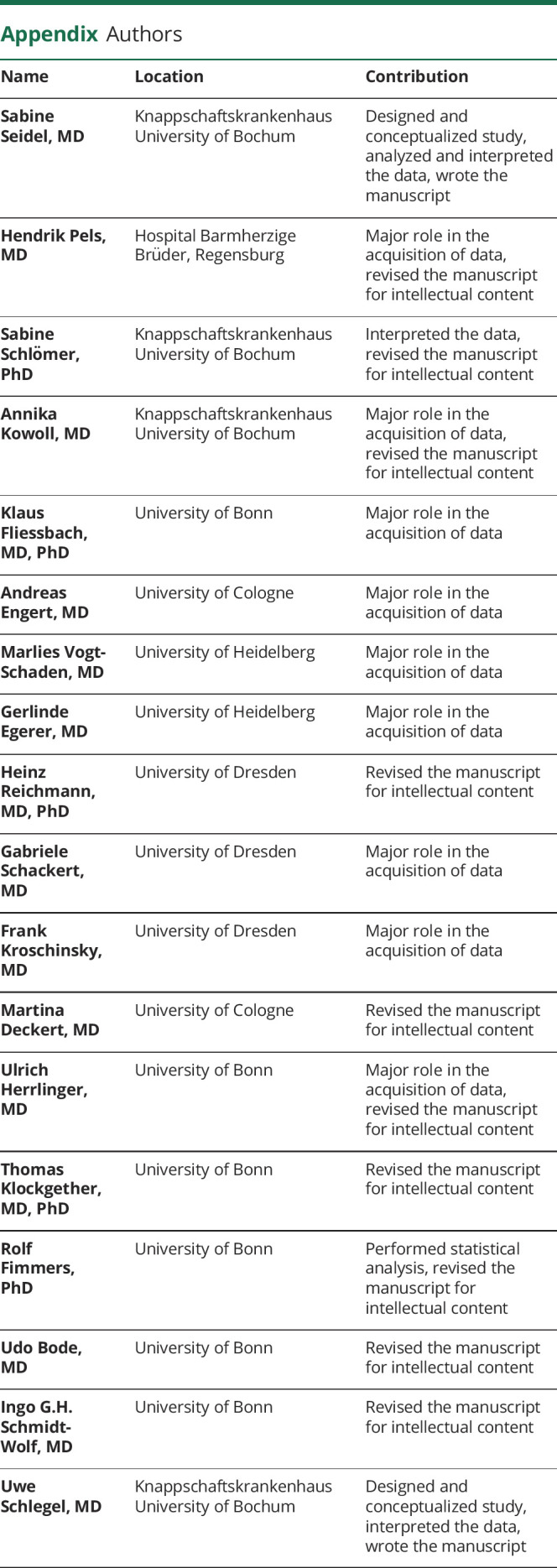

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

Dr. Seidel, Dr. Pels, Dr. Schlömer, Dr. Kowoll, Dr. Fliessbach, Dr. Engert, Dr. Vogt-Schaden, Dr. Egerer, Dr. Reichmann, and Dr. Schackert report no disclosures. Dr. Kroschinsky has received honoraria as a speaker and as an advisory board member from Roche and financial support for scientific investigations from Riemser. Dr. Deckert reports no disclosures. Dr. Herrlinger reports grants and personal fees from Roche; personal fees and nonfinancial support from Medac and Bristol-Myers Squibb; personal fees from Novocure, Janssen, Novartis, Daichii Sankyo, Riemser, Noxxon, AbbVie, and Bayer. Dr. Klockgether, Dr. Fimmers, Dr. Bode, and Dr. Schmidt-Wolf report no disclosures. Dr. Schlegel has received honoraria as a speaker from Novartis, GSK, medac, and as an advisory board member from Roche and Optune. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Grommes C, Rubenstein JL, DeAngelis LM, Ferreri AJM, Batchelor TT. Comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment of newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. Neuro Oncol 2018;21:296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenstein JL, His ED, Johnson JL, et al. Intensive chemotherapy and immunotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: CALGB 50202 (Alliance 50202). J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3061–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Illerhaus G, Kasenda B, Ihorst G, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: a prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2016;3:e388–e397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omuro AMP, Correa DD, DeAngelis LM, et al. R-MPV followed by high-dose chemotherapy with TBC and autologous stem-cell transplant for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. Blood 2015;125:1403–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreri AJM, Cwynarski K, Pulczynski E, et al. Whole-brain radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation as consolidation strategies after high-dose methotrexate-based chemoimmunotherapy in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: results of the second randomisation of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2017;4:e510–e523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houillier C, Taillandier L, Dureau S, et al. Radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation for primary CNS lymphoma in patients 60 years of age and younger: results of the intergroup ANOCEF-GOELAMS randomized phase II PRECIS study. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:823–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angelov L, Doolittle ND, Kraemer DF, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption and intra-arterial methotrexate-based therapy for newly diagnosed primary CNS Lymphoma: a multi-institutional experience. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3503–3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris PG, Correa DD, Yahalom J, et al. Rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine, and vincristine followed by consolidation reduced-dose whole-brain radiotherapy and cytarabine in newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: final results and long-term outcome. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3971–3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrey LE, Yahalom JDL. Long-term survival in primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher B, Seiferheld W, Schultz C, et al. Secondary analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group study (RTOG) 9310: an intergroup phase II combined modality treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurooncol 2005;74:201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien PC, Roos DE, Pratt G, et al. Combined-modality therapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: long-term data from a phase II multicenter study. Neuro Oncol 1999;1:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omuro AMP, Kim AK, Correa DD, et al. Delayed neurotoxicity in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1595–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doolittle ND, Korfel A, Lubow MA, et al. Long-term cognitive function, neuroimaging, and quality of life in primary CNS lymphoma. Neurology 2013;81:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pels H, Schmidt-Wolf IGH, Glasmacher A, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: results of a pilot and phase II study of systemic and intraventricular chemotherapy with deferred radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4489–4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juergens A, Pels H, Rogowski S, et al. Long-term survival with favorable cognitive outcome after chemotherapy in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Neurol 2010;67:182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Küker W, Nägele T, Thiel E, Weller M, Herrlinger U. Primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSL): MRI response criteria revised. Neurology 2005;65:1129–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinbeck JA, Stuplich M, Blasius E, et al. Relapse of primary central nervous system lymphoma 13 years after high-dose methotrexate-based polychemotherapy. J Clin Neurosci 2011;18:1554–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nayak L, Hedvat C, Rosenblum MK, Abrey LE, DeAngelis LM. Late relapse in primary central nervous system lymphoma: clonal persistence. Neuro Oncol 2011;13:525–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pels H, Montesinos-Rongen M, Schaller C, et al. Clonal evolution as pathogenetic mechanism in relapse of primary CNS lymphoma. Neurology 2004;63:167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattori K, Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Kusakabe M, et al. Genetic evidence implies that primary and relapsed tumors arise from common precursor cells in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Cancer Sci 2019;110:401–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seidel S, Korfel A, Kowalski T, et al. HDMTX-based induction therapy followed by consolidation with conventional systemic chemotherapy and intraventricular therapy (modified Bonn protocol) in primary CNS lymphoma: a monocentric retrospective analysis. Neurol Res Pract 2019;2:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data can be shared by request from any qualified investigator.