Abstract

PURPOSE:

Delays initiating guideline-adherent postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) are common, contribute to excess mortality, and are a modifiable target for improving survival. However, the barriers that prevent the delivery of timely, guideline-adherent PORT remain unknown. This study aims to identify the multilevel barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT and organize them into a conceptual model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Semi-structured interviews with key informants were conducted with a purposive sample of patients with HNSCC and oncology providers across diverse practice settings until thematic saturation (n = 45). Thematic analysis was performed to identify the themes that explain barriers to timely PORT and to develop a conceptual model.

RESULTS:

In all, 27 patients with HNSCC undergoing surgery and PORT were included, of whom 41% were African American, and 37% had surgery and PORT at different facilities. Eighteen clinicians representing a diverse mix of provider types from 7 oncology practices participated in key informant interviews. Five key themes representing barriers to timely PORT were identified across 5 health care delivery levels: (1) inadequate education about timely PORT, (2) postsurgical sequelae that interrupt the tight treatment timeline (both intrapersonal level), (3) insufficient coordination and communication during care transitions (interpersonal and health care team levels), (4) fragmentation of care across health care organizations (organizational level), and (5) travel burden for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients (community level).

CONCLUSION:

This study provides a novel description of the multilevel barriers that contribute to delayed PORT. Interventions targeting these multilevel barriers could improve the delivery of timely, guideline-adherent PORT and decrease mortality for patients with HNSCC.

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is diagnosed in 65,000 patients annually in the United States and results in 14,600 deaths per year.1 Standard of care for locoregionally advanced HNSCC consists of multimodal therapy that includes combinations of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.2 Unfortunately, treatment delays are common and are a key driver of mortality.3 For patients with locoregionally advanced, surgically treated HNSCC, standard of care, according to the National Comprehensive Care Network (NCCN) Guidelines, is to initiate postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) with or without concurrent chemotherapy within 6 weeks of surgery.2 The time interval between surgery and PORT is the only measure of timely care incorporated in NCCN Guidelines for HNSCC and is a measure of quality head and neck oncology care.4 Unfortunately, more than half of patients with HNSCC who are undergoing surgery and PORT experience a treatment delay,4,5 increasing their risk of recurrence and decreasing survival.3,6-8

The failure to deliver timely, guideline-adherent PORT is a major quality gap in care delivery for patients with HNSCC.4 Although studies have described risk factors for PORT delay5,9 and cancer care processes associated with that delay,10 the barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT and mechanisms underlying these delays remain unknown. The objectives of this study are to identify the barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT and develop a conceptual model of multilevel barriers to timely sequential multimodal care among patients with HNSCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To identify barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT, we performed a qualitative study in which head and neck oncology providers and patients (key informants) participated in one-on-one interviews. The study was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Institutional Review Board and reported in accordance with Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research Guidelines.11

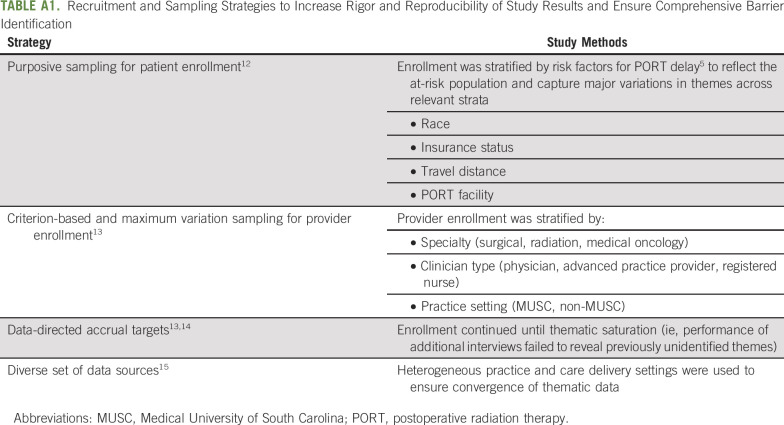

Sampling

Participants were enrolled by using purposive and criterion-based sampling strategies (Appendix Table A1, online only) to ensure the comprehensive identification of barriers to timely PORT.12-15 Participants were identified in the MUSC Head and Neck Clinic, screened by the project coordinator, and enrolled face-to-face by a study investigator after they provided written informed consent. Forty-five participants (27 patients, 18 providers) were screened; all accrued to the study. Our sample size was not determined a priori but instead reflects thematic saturation (ie, accrual stopped when performance of additional interviews failed to reveal previously unidentified themes [patterns of responses of meaning with the data]).14

Data Collection

A male and female team member trained in qualitative methods (E.M.G. and K.R.S.) conducted the interviews in person in individual sessions by using a semi-structured interview guide in a research suite. The interview guide and codebook were informed by our clinical expertise, previous research,5,10 literature review of postsurgical care transitions,16 and barriers to timely cancer care.17-19 The interview guide was pilot tested and refined to reflect language about the process of starting PORT. Interviews lasted between 9 and 49 minutes (median, 25 minutes) and used open-ended questions to elicit thought processes, knowledge, attitudes, experiences, barriers, and facilitators to timely PORT. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and entered into NVivo Version 12 for coding and analysis.

Analysis and Reflexivity

Coding and analysis were performed by E.M.G. and K.R.S. using thematic analysis (TA). TA is an inductive-deductive approach to analyzing qualitative data that generates meaning through the identification, analysis, organization, description, and reporting of themes (ie, patterns of meaning within the data).20-22 During TA, researchers start with a preliminary coding framework based on a priori codes (deductive), analyze a subset of the data, refine and develop new codes in an iterative fashion as they analyze additional data (inductive), and combine codes into themes until data are thoroughly coded.22 Themes are expressed as sentences that summarize the key meaning of the data.23,24 Although we identified facilitators to timely PORT, they generally represented the inverse of barriers, did not add explanatory value beyond barriers, and were dropped from the final codebook. After data analysis, we organized the themes into a theory-based25-29 multilevel conceptual model to facilitate understanding of the structure of care delivery and the levels at which the barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT operate30,31 and to guide the development of multilevel intervention.

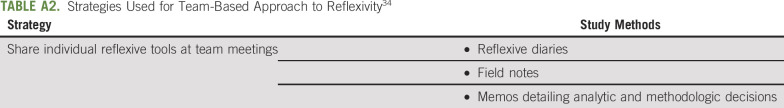

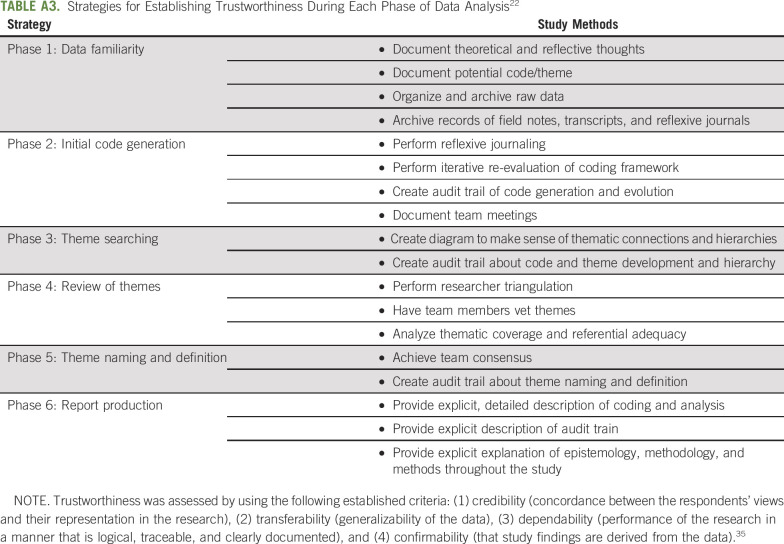

We maintained a critical realist epistemological paradigm (ie, theoretical position about the justification of knowledge and subsequent assumptions about the nature of the data)22,32 that was congruent with our beliefs that a qualitative approach can generate knowledge about how barriers to timely initiation of PORT can explain and be responsible for the observed phenomena.33 We used a team approach to reflexivity (ie, the conscious and systematic attention to the effect of the researcher on knowledge construction)34 (Appendix Table A2, online only) and took numerous steps to ensure trustworthiness and rigor during data analysis22,35 (Appendix Table A3, online only).

RESULTS

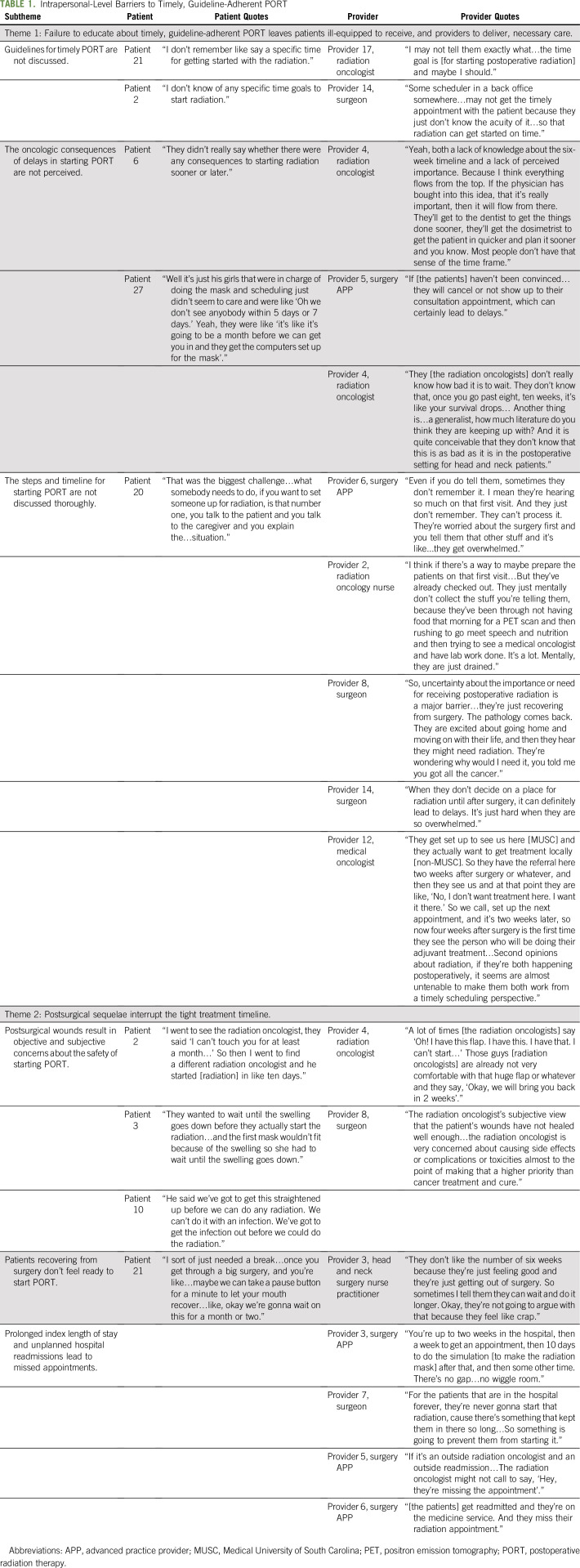

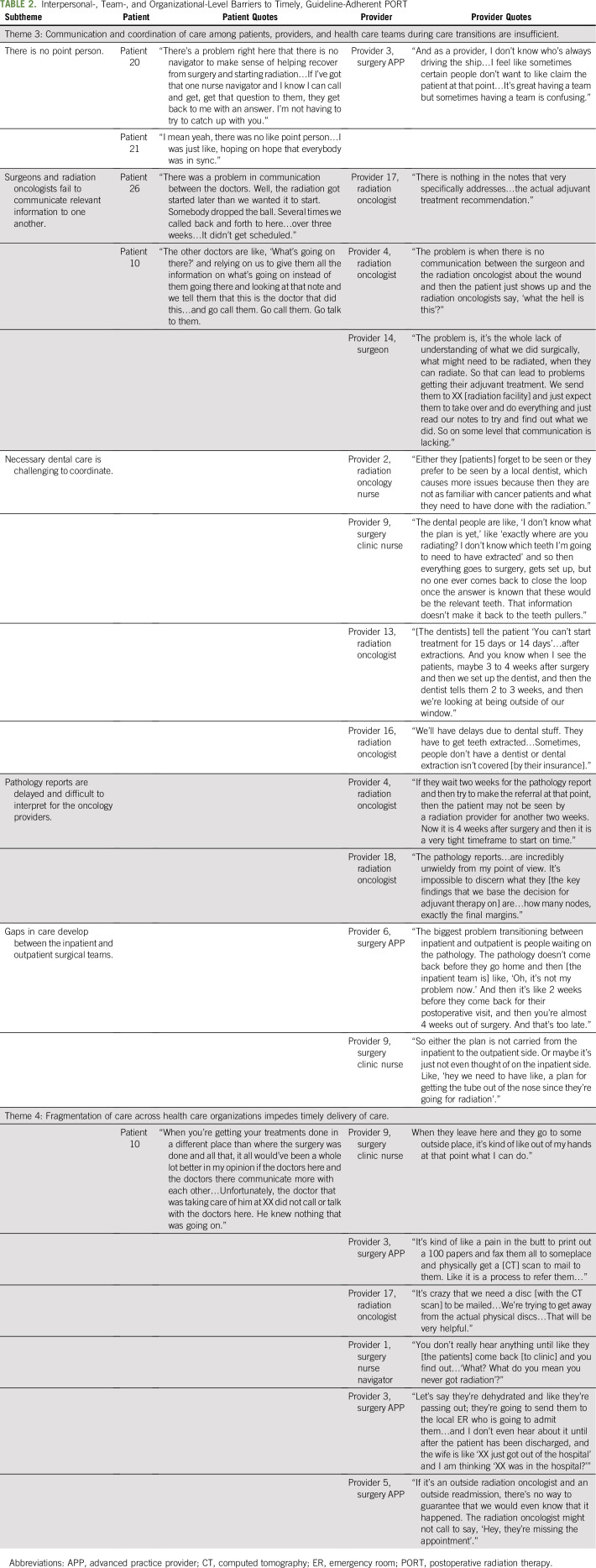

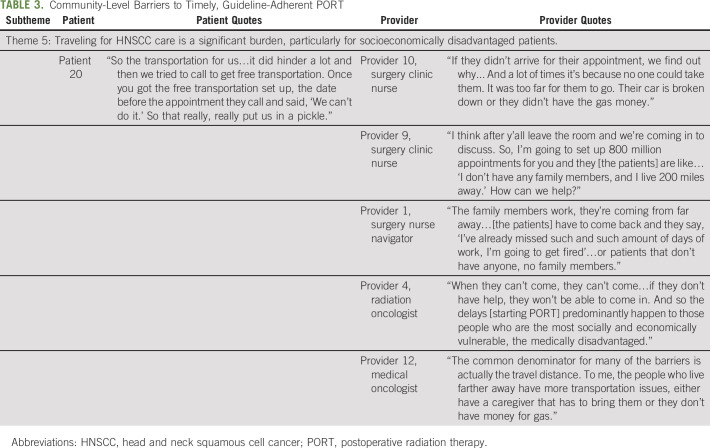

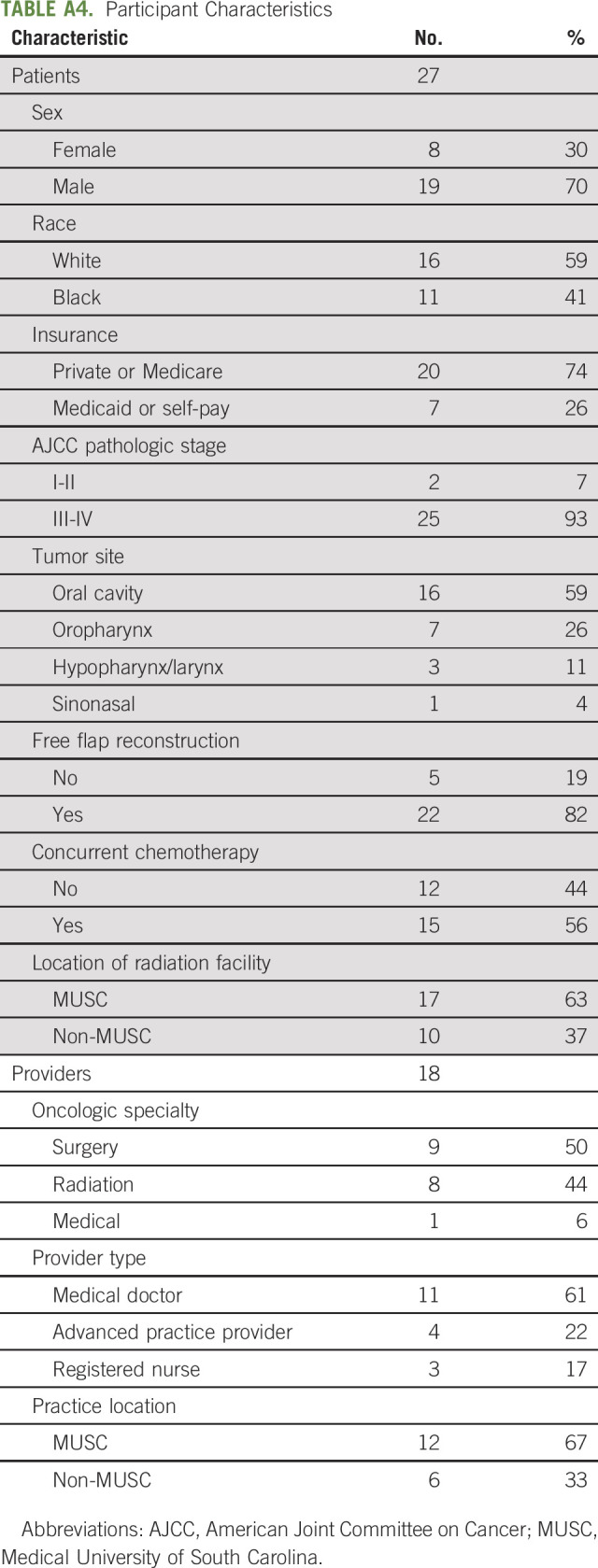

Of the 27 patients, 70% were male, 41% were African American, 26% had Medicaid or no insurance, 93% had American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage III to IV HNSCC, 56% received concurrent chemoradiation, and 37% had surgery and PORT at different facilities (Appendix Table A4, online only). Forty-four percent of providers were radiation oncologists, 61% were physicians, and 33% were not affiliated with MUSC. Five key themes of barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT were identified: (1) inadequate education about timely PORT, (2) postsurgical sequelae that interrupt the tight treatment timeline, (3) insufficient care coordination and communication during care transitions, (4) fragmentation of care across health care organizations that impedes care delivery, and (5) travel for HNSCC care as a burden for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. We describe each theme, expressed as a sentence, that describes the major findings of a barrier to timely, guideline-adherent PORT, and we include illustrative quotes supplemented by additional quotes in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

TABLE 1.

Intrapersonal-Level Barriers to Timely, Guideline-Adherent PORT

TABLE 2.

Interpersonal-, Team-, and Organizational-Level Barriers to Timely, Guideline-Adherent PORT

TABLE 3.

Community-Level Barriers to Timely, Guideline-Adherent PORT

Theme 1: A failure to educate about timely, guideline-adherent PORT leaves patients ill-equipped to receive, and providers to deliver, necessary care.

Almost universally, patients did not know that national treatment guidelines recommend starting PORT within 6 weeks of surgery, and ancillary staff were not made aware of guidelines for timely PORT, both of which led to delays in scheduling appointments (Table 1). There was a concern that some radiation oncologists, particularly those with a more general radiation oncology practice, did not appreciate the consequences of delayed PORT for patients with HNSCC. As a result, patients were not convinced of the importance of starting PORT and would skip necessary appointments, which would lead to delays.

In addition, patients were not adequately educated regarding the numerous steps required to initiate PORT and the associated timeline for each step. Providers believed that patients and caregivers were too overwhelmed to retain information about timely PORT in the hectic preoperative setting or while recovering from surgery in the hospital; thus, they omitted educating the patient until well after surgery:

“Even if you do tell them, sometimes they don’t remember it. I mean they’re hearing so much on that first visit. And they just don’t remember. They can’t process it. They’re worried about the surgery first and you tell them that other stuff and it’s like...they get overwhelmed” (Provider 6; surgery advanced practice provider [APP]).

However, patients said that the lack education about the steps to start PORT was a key barrier:

“That was the biggest challenge…what somebody needs to do, if you want to set someone up for radiation, is that number one, you talk to the patient and you talk to the caregiver and you explain the…situation” (Patient 20).

Theme 2: Postsurgical sequelae after complex head and neck surgery interrupt the tight treatment timeline.

After major head and neck surgery, which often includes complex reconstructions, patients and providers were forced to navigate a challenging array of postsurgical sequelae that could interrupt the tight treatment timeline and result in a delay starting PORT (Table 2). Objective surgical site complications (eg, fistulae, infections) can necessitate a delay in starting radiation to allow for more healing. However, there was subjectivity in determining whether a postsurgical wound was sufficiently healed to start PORT, contributing to delays:

“I went to see the radiation oncologist, they said I can’t touch you for at least a month…So then I went to find a different radiation oncologist and he started [radiation] in like ten days” (Patient 2).

Complex reconstructions, even when healing well, were a source of uncertainty and thus delay:

“A lot of time [the radiation oncologists] say ‘Oh! I have this flap. I have this. I have that. I can’t start’…Those guys [radiation oncologists] are already not very comfortable with that huge flap or whatever and they say, ‘Okay, we will bring you back in 2 weeks’.” (Provider 4; radiation oncologist).

Importantly, even when surgical wounds were healing well, radiation could be delayed because patients recovering from their extensive surgery did not feel ready to continue the marathon by starting radiation:

“I sort of just needed a break…once you get through a big surgery, and you’re like…maybe we can take a pause button for a minute to let your mouth recover…like, okay we’re gonna wait on this for a month or two” (Patient 21).

Finally, postsurgical sequelae often resulted in prolonged hospitalizations and hospital readmissions, making for a very tight treatment timeline in which any deviation could result in a delay:

“You‘re up to two weeks in the hospital, then a week to get an appointment, then 10 days to do the simulation [to make the radiation mask] after that and then some other time. There‘s no gap…no wiggle room” (Provider 3; surgery APP).

Theme 3: Communication and care coordination among patients, providers, and health care teams during care transitions are insufficient.

As patients transition across the numerous health care teams (eg, surgical, radiation, medical oncology, dental) and from inpatient to outpatient care, communication and care coordination were insufficient (Table 2). Because there were so many teams and care transitions involved, it was unclear to patients and providers who was in charge at any point in time. In addition, care coordination across teams was often out of sync, leading to delays:

“There was a problem in communication between the doctors. Well, the radiation got started later than we wanted it to start. Somebody dropped the ball. Several times we called back and forth to here…over three weeks…It didn‘t get scheduled” (Patient 26).

Necessary preradiotherapy dental extractions were particularly challenging to coordinate:

“Either they [patients] forget to be seen or they prefer to be seen by a local dentist, which causes more issues because then they are not as familiar with cancer patients and what they need to have done with the radiation” (Provider 2; radiation oncology nurse).

Communication between the radiation and surgical teams was primarily restricted to indirect communication via the medical record, which lacked sufficient clinical detail:

“We send them to XX [radiation facility] and just expect them to take over and do everything and just read our notes to try and find out what we did. So on some level that communication is lacking.” (Provider 14; surgeon).

In addition to the challenges of coordinating care during transitions between teams, providers struggled to coordinate across transitions between care settings (eg, inpatient to outpatient after hospital discharge):

“The biggest problem transitioning between inpatient and outpatient is people waiting on the pathology. The pathology report doesn‘t come back before they go home and then [the inpatient team is] like, ‘Oh, it‘s not my problem now.’ And then it‘s like 2 weeks before they come back for their postop and then you‘re almost 4 weeks out of surgery. And that‘s too late.” (Provider 6; surgery APP).

Theme 4: Fragmentation of care across health care organizations impedes timely delivery of care.

Fragmentation of care across health care organizations, required for patients who have surgery and PORT at different facilities, impeded delivery of care necessary for timely PORT (Table 3). Providers felt limited in their ability to cross organizational boundaries to help get radiation started:

“When they leave here and they go to some outside place it‘s kind of like out of my hands at that point what I can do.” (Provider 9; surgery clinic nurse).

Because different health care organizations had incompatible electronic medical records that precluded electronic sharing of information, the clinical information needed to start PORT was transmitted by fax and physical mail. This cumbersome and time-consuming process delayed receipt of information necessary to meet the tight treatment timeline:

“It’s kind of like a pain in the butt to print out a 100 papers and fax them all to someplace and physically get a [computed tomography (CT)] scan to mail to them. Like it is a process to refer them…” (Provider 3; surgery APP).

The circumscribed authority for crossing organizational boundaries, combined with the challenges of sharing clinical information, impeded referral tracking and follow-up across health care organizations:

“You don’t really hear anything until like they [the patients] come back [to clinic] and you find out…’What? What do you mean you never got radiation’?” (Provider 1; surgery nurse navigator)

Theme 5: Traveling for HNSCC care is a significant burden, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients.

Because complex HNSCC surgical procedures are frequently regionalized to high volume facilities, patients often have to travel significant distances for care. The multidisciplinary nature of HNSCC care and logistics of surgical care result in multiple clinical encounters (before, during, and after surgery). Patients who lack reliable transportation, financial resources, or a caregiver to assist with travel were disproportionately burdened, missed necessary clinical encounters, and experienced delays (Table 3):

“If they didn‘t arrive for their appointment, we find out why...And a lot of times it‘s because no one could take them. It was too far for them to go. Their car‘s broken down or they didn‘t have the gas money.” (Provider 10; surgery clinic nurse).

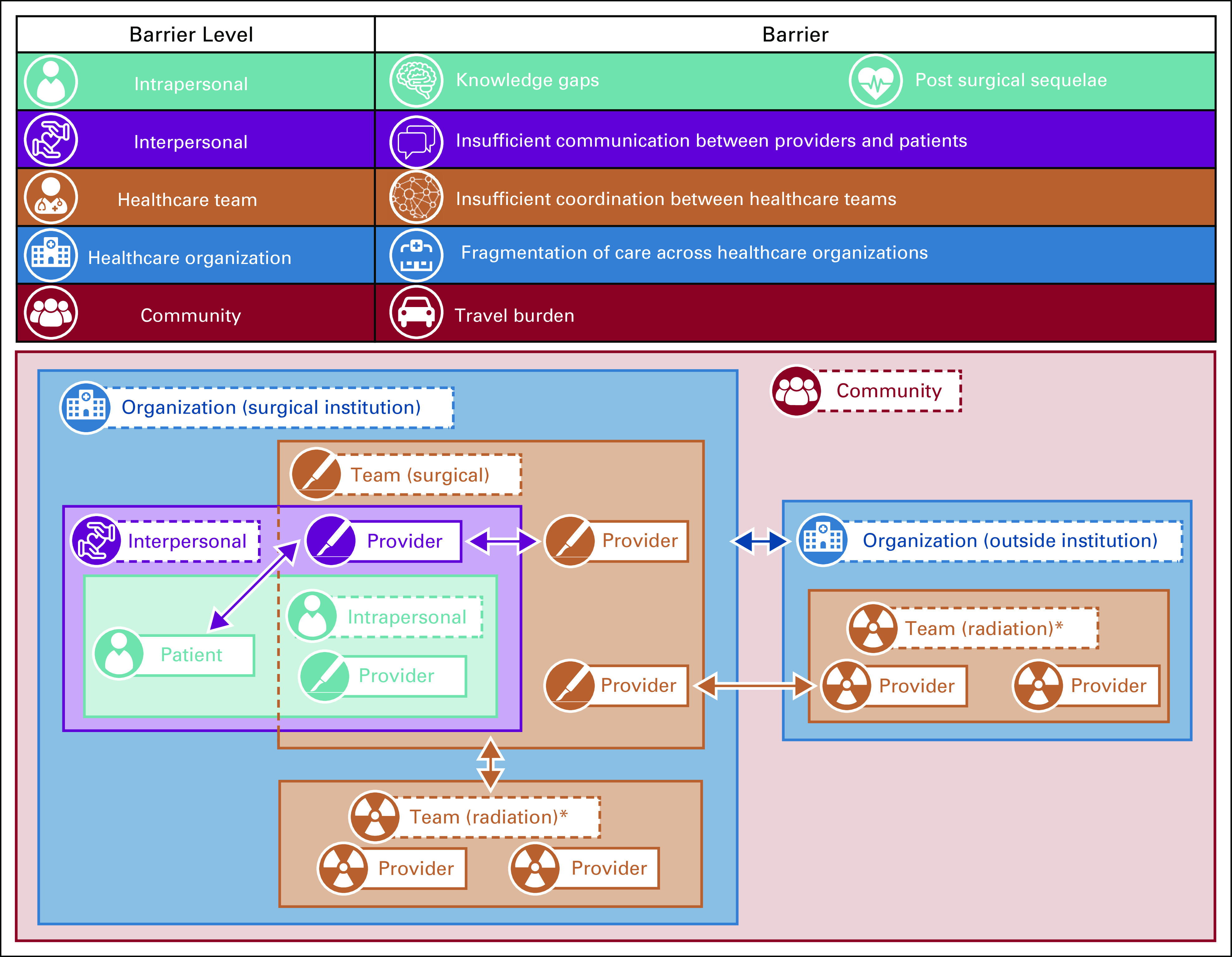

Conceptual Model

Our conceptual model (Fig 1) provides a framework for understanding the multilevel barriers to timely sequential multimodal delivery of cancer care (eg, surgery followed by PORT). By organizing themes at levels of health care delivery, the model reflects individual behaviors for both patients and providers and reciprocal interactions between patients and providers and among providers. It also shows that clinicians are embedded within and across numerous health care teams (eg, surgical oncology, radiation oncology), that teams are situated within and across health care systems, and that health care systems are located within communities.30

FIG 1.

Conceptual model inset: Barriers to timely, guideline-adherent postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) after surgery for head and neck cancer occur at multiple levels (intrapersonal, interpersonal, team, organizational, and community). Because cancer delivery occurs in a multilevel system in which behavior is affected by multiple levels of reciprocal interactions, key themes of barriers to the delivery of timely PORT reflect (1) individual behaviors of patients and providers (blue box), (2) reciprocal interactions between patients and providers and patients and caregivers (green box), (3) clinicians embedded within and across numerous health care teams (red boxes), (4) teams situated within and across multiple health care systems (purple boxes), and (5) health care systems located within communities across a geographic space (orange box). (*) Although the conceptual model depicts only 2 teams (surgical and radiation oncology), additional teams within and across organizations that routinely participate in the delivery of (and thus barriers to) timely PORT include medical oncology, dental, oral surgery, maxillofacial prosthodontics, speech language pathology, general surgery/gastroenterology/interventional radiology, and primary care.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified 5 themes that explain the mechanisms underlying delayed, guideline-nonadherent PORT after surgery for HNSCC: (1) inadequate education about timely PORT, (2) postsurgical sequelae that interrupt the tight treatment timeline, (3) insufficient communication and coordination of care during care transitions, (4) fragmentation of care across health care organizations, which impedes care delivery, and (5) travel for HNSCC care as a burden for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. Using these themes, we developed a theory-based, multilevel conceptual model to enhance our understanding of the delivery of sequential multimodal cancer care to patients with HNSCC and to guide the development of multilevel intervention.

These foundational qualitative data will enable future studies to gather prospective quantitative data about barriers to timely PORT that will characterize the frequency, number, timing, and dynamic evolution of barriers as patients progress through treatment. Our findings are hypothesis generating for quantitative studies to evaluate the strength of the association between these barriers and PORT delay (ie, to quantitatively compare how the number and/or type of barriers differ between patients who do and do not experience a delay). Importantly, our findings extend previous research on barriers to cancer screening, treatment initiation, and postsurgical care transitions by providing a theory-driven conceptual model to explain the determinants of timely multimodal sequential cancer care for patients with HNSCC who are undergoing surgery and PORT.

Our findings have significant translational importance as a way of informing the design of multilevel interventions to improve the delivery of timely, guideline-adherent PORT after surgery for HNSCC. Our data suggest that for an intervention to decrease PORT delays, it should target multiple levels (eg, intrapersonal and interpersonal) and address specific barriers related to inadequate education about timely PORT, postsurgical sequelae, insufficient communication and coordination of care during care transitions, fragmentation of care across health care organizations, and travel burden. Whether an intervention needs to target all barriers (or levels) or only a few critical barriers (or levels) is not known and should be explored in future research.

Finally, our rigorous qualitative approach also allowed us to overcome key methodologic limitations of previous studies about PORT delay. Previous research, which focused on risk factors for PORT delay, identified that race, social determinants of health, travel distance, and care fragmentation were associated with delays.5,9 Themes identified in this study reflect previously identified risk factors for PORT delay. However, this study goes beyond risk factors and correlations to identify (and conceptualize) the mechanisms responsible for PORT delay,36 thus enhancing our understanding of the determinants of timely, multimodal HNSCC care delivery and facilitating future translational research to decrease treatment delays.37

An important study limitation is that all patients underwent HNSCC surgery at a single institution. However, our themes are likely generalizable to other institutions because the prevalence of delays and risk factors for delayed PORT at MUSC10 resemble national data,5 and because we used numerous strategies12-15 to increase generalizability and ensure comprehensive identification of barriers. Nevertheless, additional qualitative work in other settings will help establish the generalizability of our findings. Because of our selected analytic approach, we could not compare the barriers faced by patients who experienced a delay when starting guideline-adherent PORT with those faced by patients who received PORT in a timely fashion. Therefore, future quantitative research is necessary to characterize how the number, type, and/or timing of barriers differs between patients with and without a delay.

In summary, we identified 5 themes that explain the mechanisms underlying delays in starting guideline-adherent PORT after HNSCC surgery. These barriers, which occur at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, health care team, organizational, and community levels, inform a theory-based, multilevel conceptual model for understanding the delivery of timely, guideline-adherent PORT to patients with HNSCC. Interventions targeting these barriers could improve the delivery of timely, guideline-adherent PORT and decrease mortality for patients with HNSCC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the head and neck patients, head and neck health care providers, and Julie Barroso, RN, PhD, for their time and expertise.

Appendix

TABLE A1.

Recruitment and Sampling Strategies to Increase Rigor and Reproducibility of Study Results and Ensure Comprehensive Barrier Identification

TABLE A2.

Strategies Used for Team-Based Approach to Reflexivity34

TABLE A3.

Strategies for Establishing Trustworthiness During Each Phase of Data Analysis22

TABLE A4.

Participant Characteristics

SUPPORT

This work was supported by Grants No. K12CA157688, K08CA237858, and P30CA138313 (Biostatistics Shared Resource of the Hollings Cancer Center) from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and No. DDCF2015209 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (E.M.G.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Evan M. Graboyes, Elizabeth A. Calhoun, Anand K. Sharma, David M. Neskey, Katherine R. Sterba

Financial support: Evan M. Graboyes

Administrative support: Chanita Hughes Halbert, Elizabeth A. Calhoun, Jessica McCay

Provision of study materials or patients: Terry A. Day

Collection and assembly of data: Evan M. Graboyes, Chanita Hughes Halbert, Courtney H. Marsh, Jessica McCay, Terry A. Day, Anand K. Sharma, Katherine R. Sterba

Data analysis and interpretation: Evan M. Graboyes, Chanita Hughes Halbert, Hong Li, Graham W. Warren, Anthony J. Alberg, Elizabeth A. Calhoun, Brian Nussenbaum, Terry A. Day, John M. Kaczmar, Anand K. Sharma, Katherine R. Sterba

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Barriers to the Delivery of Timely, Guideline-Adherent Adjuvant Therapy Among Patients With Head and Neck Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

John M. Kaczmar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Regeneron

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2020: Head and Neck Cancers. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf

- 3.Graboyes EM, Kompelli AR, Neskey DM, et al. Association of treatment delays with survival for patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145:166–177. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cramer JD, Speedy SE, Ferris RL, et al. National evaluation of multidisciplinary quality metrics for head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:4372–4381. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graboyes EM, Garrett-Mayer E, Sharma AK, et al. Adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for time to initiation of postoperative radiation therapy for patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:2651–2660. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graboyes EM, Garrett-Mayer E, Ellis MA, et al. Effect of time to initiation of postoperative radiation therapy on survival in surgically managed head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:4841–4850. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho AS, Kim S, Tighiouart M, et al. Quantitative survival impact of composite treatment delays in head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2018;124:3154–3162. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen MM, Harris JP, Orosco RK, et al. Association of time between surgery and adjuvant therapy with survival in oral cavity cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158:1051–1056. doi: 10.1177/0194599817751679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shew M, New J, Bur AM. Machine learning to predict delays in adjuvant radiation following surgery for head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160:1058–1064. doi: 10.1177/0194599818823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janz TA, Kim J, Hill EG, et al. Association of care processes with timely, equitable postoperative radiotherapy in patients with surgically treated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:1105–1114. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patton M. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. ed 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemper E, Stringfield S, Teddlie C.Mixed methods sampling strategies in social science researchinTashakkori A, Teddlie C.Handbook of Mixed Methods in the Social and Behavioral Sciences ed 2Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooke BS, Slager SL, Swords DS, et al. Patient and caregiver perspectives on care coordination during transitions of surgical care. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8:429–438. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: The Patient Navigation Research Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju115. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendren S, Chin N, Fisher S, et al. Patients’ barriers to receipt of cancer care, and factors associated with needing more assistance from a patient navigator. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:701–710. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30409-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramachandran A, Snyder FR, Katz ML, et al. Barriers to health care contribute to delays in follow-up among women with abnormal cancer screening: Data from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer. 2015;121:4016–4024. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12:297–298. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowell L, Norris J, White D, et al. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandelowski M, Leeman J. Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1404–1413. doi: 10.1177/1049732312450368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connelly LM, Peltzer JN. Underdeveloped themes in qualitative research: Relationship with interviews and analysis. Clin Nurse Spec. 2016;30:52–57. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Theory at a Glance: A Guide For Health Promotion Practice. (ed 2) https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/theories_project/theory.pdf

- 26.Sallis JF, Owen N.Ecological models of health behaviorinGlanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K.Health Behavior. Theory, Research, and Practice ed 5San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 201543–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Measures Atlas Update: Chapter 2. What is Care Coordination? http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/coordination/atlas2014/chapter2.html

- 28.Holt-Lunstad J, Uchino BN.Social support and healthinGlanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K.Health Behavior: Theory, Research, Practice ed 5San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2015183–204. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skinner CS, Tiro J, Champion VL: The Health Belief ModelinGlanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K.(eds)Health Behavior. Theory, Research, and Practice ed 5San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 201575–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: Understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:2–10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taplin SH, Yabroff KR, Zapka J. A multilevel research perspective on cancer care delivery: The example of follow-up to an abnormal mammogram. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1709–1715. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carter SM, Little M. Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: Epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1316–1328. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N.Choosing a qualitative research methodinHarper D, Thompson AR.Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners Wiley-Blackwell; 201126–44. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, et al. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:26–44. doi: 10.1177/104973299129121677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lincoln YS, Guba EG, Pilotta JJ. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teddlie C, Tashakkori A.Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciencesinTashakkori A, Teddlie C.Handbook of Mixed Methods in the Social and Behavioral Sciences ed 1Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 201013–50. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graboyes EM, Hughes-Halbert C. Delivering timely head and neck cancer care to an underserved urban population: Better late than never, but never late is better. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145:1010–1011. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]