Abstract

Introduction

The negative impacts of COVID-19 have rippled through every facet of society. Understanding the multidimensional impacts of this pandemic is crucial to identify the most critical needs and to inform targeted interventions. This population survey study aimed to investigate the acute phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in terms of perceived threats and concerns, occupational and financial impacts, social impacts and stress between 3 April and 15 May 2020.

Methods

6040 participants are included in this report. A multivariate linear regression model was used to identify factors associated with stress changes (as measured by the Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)) relative to pre-outbreak retrospective estimates.

Results

On average, PSS scores increased from low stress levels before the outbreak to moderate stress levels during the outbreak (p<0.001). The independent factors associated with stress worsening were: having a mental disorder, female sex, having underage children, heavier alcohol consumption, working with the general public, shorter sleep duration, younger age, less time elapsed since the start of the outbreak, lower stress before the outbreak, worse symptoms that could be linked to COVID-19, lower coping skills, worse obsessive–compulsive symptoms related to germs and contamination, personalities loading on extraversion, conscientiousness and neuroticism, left wing political views, worse family relationships and spending less time exercising and doing artistic activities.

Conclusion

Cross-sectional analyses showed a significant increase from low to moderate stress during the COVID-19 outbreak. Identified modifiable factors associated with increased stress may be informative for intervention development.

Trial registration number

NCT04369690; Results.

Keywords: public health, COVID-19, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Comprehensive picture of the psychological, financial and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Large population-based study with a lifespan perspective, but imperfect representativeness due to sampling bias.

Comparison of outbreak measures to pre-outbreak estimates allows for a better understanding of the extent to which COVID-19 disrupted people’s daily lives, but may be sensitive to recall bias.

Identification of modifiable factors associated with the psychological response to the pandemic.

Introduction

An outbreak of COVID-19, a cluster of acute febrile respiratory illness, was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on 11 March 2020, after infections were reported in 110 countries and territories. As of 4 June 2020, COVID-19 had spread to 216 countries and territories, infected 6 416 828 individuals and caused 382 867 deaths worldwide.2 This pandemic has created profound economic and social disruption, with the potential for widespread psychological impacts. Given the lack of specific treatments for the prevention and management of the COVID-19 infection and the rapid acceleration of the virus transmission, the negative impacts of COVID-19 are rippling through every aspect of society.3 Markedly, guidelines and new regulations have been put in place to promote self-isolation in order to limit the spread of the virus. As a result, most inpatient and outpatient health services cut down non-essential services. Several offices and businesses asked their employees to work from home; others reduced work hours or terminated jobs. Schools and universities were closed with some of them offering distance education. Overall, the pandemic situation has changed the core aspects of people’s lives in a unique and complex manner.

Early COVID-19 studies from China, India, Brazil, Paraguay and the USA indicated high levels of stress with associated sleep problems, poor life satisfaction and mental illness.4–8 Findings from a comparative study suggest that Western countries may have higher stress levels during the pandemic than Eastern countries, highlighting the needs for additional investigations in Western countries such as Canada.9 In the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, roughly 35% of 50 000 residents in China were experiencing psychological distress.7 In San Francisco (USA), there was an eightfold increase (from 7% to 66%) in feeling distressed compared to before the pandemic.10 In Australia, almost 80% of survey respondents reported moderate to extreme levels of uncertainty about the future, half reported feeling lonely and half reported moderate to extreme worry about their financial situation.11 Some financial stressors, such as employment loss, have also been associated with greater symptoms of depression and COVID-19-related concern.6 However, many of the previous studies did not estimate temporal changes before and during the outbreak, making it difficult to disentangle difficulties emerging in response to the outbreak from pre-existing ones. Also, many focused on isolated aspects of the consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak without presenting a comprehensive picture and thus have limited capacity to identify potential factors modulating the range of psychological responses to the outbreak.

The nature and extent of the outbreak consequences are bound to differ considerably from one individual to another and to be influenced by a range of demographic, occupational and physical/mental health factors.7 11 12 There is thus a need for comprehensive investigations to identify potential factors modulating psychological responses to this complex situation. Furthermore, most studies to date adopted a broad, representational sampling of adults, but increased efforts to reach individuals at elevated risk for negative outcomes and a lifespan perspective incorporating younger to older age ranges holds particular benefits in informing both prevention and intervention initiatives.

The current report presents the cohort characteristics and baseline observations from an ongoing longitudinal survey launched during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Perceived threats and concerns, occupational, financial and social distancing behaviours, impacts on social life as well as psychological stress changes relative to retrospective pre-outbreak estimates are reported.

Methods

Study design

A comprehensive longitudinal online survey was distributed via websites, social media and multiple organisations and hospitals across Canada. This recruitment strategy (see online supplemental section for details) was used to target three core groups: people with chronic mental or physical illnesses, healthcare providers and the general population. While subsequent reports will focus on specific subgroups, the current report introduces the full cohort.

bmjopen-2020-043805supp001.pdf (338.2KB, pdf)

The sole inclusion criterion was to be 12 years of age or older. The survey was available in English and French, nested in a secured access online platform (www.qualtrics.com), and designed on a decisional tree structure. It included a set of validated questionnaires and custom-built questions pertaining to the pandemic (see online supplemental section).

The survey was designed to address the following primary areas of interest: (1) symptoms related to COVID-19 and rates of positive tests; (2) physical and mental health conditions; (3) access to healthcare services4; (4) social distancing practices; (5) consequences of the outbreak for family, work-related and financial outcomes; (6) factors and coping mechanisms that may be protective against adverse health, psychosocial and financial impacts; (7) organisational support, work resources and difficulties, degree of moral distress and moral resilience in healthcare staff. The survey also included general demographics and indices for geocoding and socioeconomic status. To enable future comparisons, questions were aligned wherever possible with previous surveys such as those used by Census Canada and recent COVID-19 surveys circulated in China.13 14 The survey included a briefer version for healthcare workers and an adapted version for adolescents. At the start of the survey, participants were informed that they had the choice to skip items. Median completion time was 53.1 min (IQR: 38.6 min).

Themes covered in the current report include factors linked to the pandemic (eg, testing, perceived threat and concerns); occupational and financial life; social life and psychological stress. Retrospective questions were used to estimate temporal changes from ‘before the outbreak’ (ie, in the last month before the outbreak) to ‘during the outbreak’ (ie, in the 7 days prior to filling out the survey). The survey was developed and conducted following guidelines from the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys.15 Additional information about the survey and the psychometric properties of validated scales included are outlined in online supplemental material. Electronic informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Patient and public involvement

People from the general public, individuals with mental disorders, and healthcare professionals were consulted during the survey development and testing phase. They were asked to provide feedback on the survey content, both in terms of prioritising the most important questions (thereby influencing outcome measures) and the clarity of question formulation. They were also asked to comment on the survey format, notably in terms of the layout of the questions on the online platform, the general survey length and the distinct survey sections specifically targeting certain subgroups (thereby influencing the study design). These individuals were not directly involved in active recruitment or the dissemination plan for the study.

Primary outcome: psychological stress

Respondents retrospectively assessed their stress levels on the Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)16 for the last month before the outbreak (ie, pre-outbreak) and for the past 7 days (ie, during the outbreak). PSS scores were analysed continuously (ie, scale of 0–40)17 and categorically based on established thresholds: 0–13 (low stress), 14–26 (moderate stress) and 27–40 (high stress) and previously estimated minimal clinically important change corresponding to a 28% relative change.17

Factors hypothesised a priori to be associated with stress changes were pre-outbreak stress level, time elapsed since the pandemic declaration by the WHO, age, sex, education level, total family income, employment status, working with the general public, political views, having underage children, having travelled abroad in the past 60 days, index reflective of the number and severity of potential COVID-19 symptoms (ie, COVID-19 symptoms index), the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS) contamination subscale, Big 5 Personality subscales, Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS), having a mental disorder, alcohol and drugs use, having a physical condition at risk for COVID-19, sleep duration, quality of family relationships, amount of time spent outdoors, interacting with other people, following the news on COVID-19, and engaging in physical and artistic activities.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise survey respondents. To assess changes before and during the outbreak, χ2 analyses, paired t-tests/Wilcoxon tests and McNemar-Bowker tests were used as appropriate. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess the unadjusted cross-sectional temporal evolution of PSS change scores across the study period.

Multivariate linear regression was used to identify factors independently associated with PSS changes scores using the ‘enter’ pairwise approach with the predictors listed above. To improve sample homogeneity, this model was run solely on the subgroup of Canadian respondents. A series of multivariate linear models were also run to assess the relation between changes in stress and each independent variable separately while accounting for pre-outbreak PSS scores. Analyses were done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.23.0. Armonk, USA). Details on data cleaning procedures are provided in the online supplemental material.

Results

Survey and sample characteristics

Between April 3rd and May 15th, 2020 (ie, 23–65 days after the pandemic declaration by the WHO, a period starting around the peak of the first wave in Canada where 900–2000 new reported cases were deemed to emerge each week18), 6685 individuals consented to take part in this study and answered the first survey question. All 6040 respondents who filled out the minimally sufficient portion of the survey (90.4% of those who answered the first question; see details in online supplemental material) were included in the current report. From this sample, 81.7% respondents completed the entire survey.

Sample characteristics are presented in table 1. Respondents ranged between 12 and 83 years old. Most respondents were middle aged, women, Canadian (mostly from Ontario or Quebec), Caucasian, highly educated, lived in an urban residential area, had children, and were employed with a total yearly family income above $C40 000. More than 50% reported having a physical illness known to be at risks for adverse COVID-19 outcomes, and about 30% had a diagnosis of a mental disorder.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the survey responders at the time of the survey completion

| Total n | Missing values, % (frequency) | Mean±SD / % (frequency) | |

| Time since outbreak start (days) | 6040 | 0.0 (0) | 50.9±11.7 |

| General demographics | |||

| Age | 6034 | 0.1 (6) | 51.8±17.1 |

| Biological sex (females) | 6039 | <0.1 (1) | 70.3 (4248) |

| Gender/sex change | 5480 | 9.3 (560) | |

| Male | 31.6 (1730) | ||

| Female | 67.1 (3676) | ||

| Transexual | 0.2 (10) | ||

| Gender queer or expansive | 0.9 (50) | ||

| Other | 0.3 (14) | ||

| Current location | 6005 | 0.6 (35) | |

| Canada | 97.3 (5845) | ||

| USA | 1.3 (79) | ||

| Others* | 0.7 (40) | ||

| France | 0.4 (26) | ||

| Australia | 0.2 (15) | ||

| Ethnicity | 5577 | 7.7 (463) | |

| Caucasian | 86.6 (4832) | ||

| Others | 5.6 (311) | ||

| Asian | 3.4 (191) | ||

| First Nation, Metis or Inuk | 2.1 (115) | ||

| Arab | 1.2 (68) | ||

| Black | 1.1 (60) | ||

| Non-citizen (vs not) | 5634 | 6.7 (406) | 6.1 (343) |

| Political views (left-wing/right-wing) | 5167 | 14.5 (873) | 44.8 (2313)/14.6 (754) |

| Education | 5495 | 0.8 (49) | |

| University certificate, diploma or degree | 63.6 (3497) | ||

| College | 21.8 (1197) | ||

| High school | 14.8 (801) | ||

| Socioeconomic, occupational and living situation | |||

| Total family income (<$C40k/$C40k to $C100k/>$C100k) | 5601 | 7.3 (439) | 11.1 (624)/40.6 (2272)/48.3 (2705) |

| Employment status | 5958 | 1.4 (82) | |

| Unemployed/retired/student | 12.8 (764)/30.6 (1822)/3.6 (213) | ||

| Employed | 53.0 (3159) | ||

| Having work involves contact with the general public (vs not) | 5779 | 4.3 (261) | 14.3 (826) |

| Dwelling (house/apartment or condo) | 5417 | 10.3 (623) | 77.4 (4191)/22.6 (1226) |

| Living situation (alone/with another person/with multiple people) | 5606 | 7.2 (434) | 20.0 (1123)/44.2 (2478)/35.8 (2005) |

| Living area (rural/urban) | 5565 | 7.9 (475) | 11.8 (665)/88.2 (4910) |

| Health and risks factors | |||

| C19 Symptoms index (0–30 scale) | 6040 | 0.0 (0) | 2.1±3.6 |

| Presence of physical condition at risk for COVID-19* (vs not) | 5629 | 6.8 (411) | 52.1 (2934) |

| Sleep duration (hours; before the outbreak/during outbreak) | 4998 | 17.1 (1030) | 7.3±1.2/7.2±1.5 |

| Travelled abroad in last 60 days (vs not) | 5548 | 8.1 (492) | 11.0 (608) |

| Psychological domain | |||

| PSS scores (0–40 scale; before the outbreak /during outbreak) | 5132 | 15.0 (98) | 12.9±6.8/14.9±8.3 |

| DOCS—contamination (0–20 scale) | 4920 | 18.5 (1120) | 6.1±3.7 |

| Big 5 subscales (2–10 scale) | 4881 | 19.2 (1161) | |

| Extraversion | 6.2±2.1 | ||

| Agreeableness | 7.4±1.7 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 7.8±1.8 | ||

| Neuroticism | 5.6±2.3 | ||

| Openness to experiences | 6.9+1.9 | ||

| Brief Resilient Coping Scale (4–20 scale) | 4856 | 19.6 (1184) | 14.7±2.9 |

| Mental disorder diagnosis (vs not) | 5607 | 7.2 (433) | 29.0 (1626) |

| Social domain | |||

| Family relationship (0–100 scale; before the outbreak/during outbreak) | 5328 | 9.5 (572) | 79.5±19.9/74.7±25.4 |

| Has underage children (vs not) | 5731 | 5.1 (309) | 17.2 (985) |

| Behavioural domain | |||

| Number of alcoholic drinks/week (before the outbreak/during outbreak) | 5557 | 7.9 (476) | 4.1±6.5/4.8±6.9 |

| Number of cannabis use/week (before the outbreak/during outbreak) | 5512 | 8.6 (518) | 0.9±5.1/1.0±5.1 |

| Spent 30 min or less: | 5612 | 7.1 (428) | |

| Outdoor | 39.3 (2203) | ||

| Exercising | 47.7 (2668) | ||

| Following C19 news | 44.0 (2457) | ||

| Interacting with people in person | 50.6 (2767) | ||

| Interacting with people virtually | 39.5 (2194) | ||

| Doing an artistic activity | 75.6 (4155) | ||

Means, SD, frequencies and percentages (calculated on each item’s total sample) for main sample characteristics; location others: Armenia (n=1), Azerbaijan (n=1), Burkina (n=3), Congo (n=1), Czech Republic (n=1), Denmark (n=1), Germany (n=3), Ireland (n=1), Italy (n=1), Ivory Coast (n=1), Jamaica (n=1), Lebanon (n=1), Malaysia (n=1), Netherlands (n=3), New Zealand (n=1), Pakistan (n=1), Poland (n=1), Romania (n=2), Singapore (n=3), Spain (n=1), Sweden (n=1), UK (n=8), Vietnam (n=1), Other (n=1); gender expansive: fluid/non-binary; alcohol consumption (number of drinks per week); cannabis consumption (number of times per week), living area based on postal code.

*Physical condition at risk for COVID-19: for example, respiratory, cardiovascular or autoimmune conditions.

DOCS, Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

COVID-19 testing, perceived threats/concerns and changes relative to before the outbreak

79.3% of respondents endorsed at least two symptoms that could be linked to COVID-19 and 6.7% of respondents said they had been tested for COVID-19. Of those, 4.5% tested positive and 2.7% awaited results. Of those who had not been tested, 4.7% had contacted public health services to be tested. Within this group, 85.4% were declined testing. Rates of declined testing were similar between rural (85.0%) and urban areas (86.2%; χ2=0.02, p=0.886).

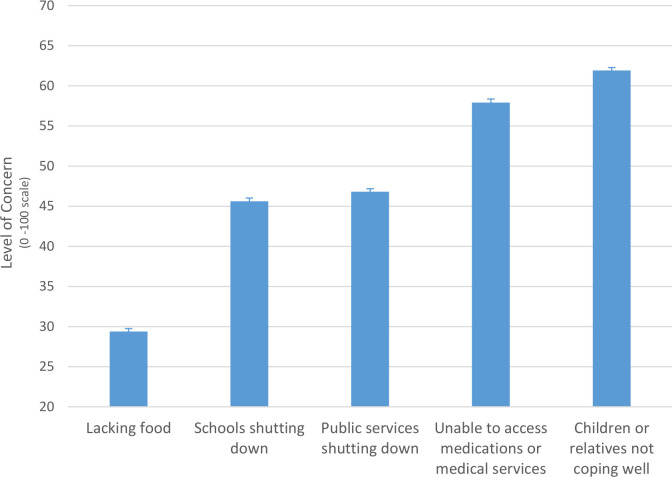

Among all respondents, 43.0% estimated that a coronavirus infection would pose high to very high threat to their health and 32.8% estimated moderate threat. A high to very high threat was estimated by 28.1% for their financial situation, 41.5% for their jobs or businesses and 62.8% for their country. Figure 1 shows the degree of concern related to different secondary effects of the outbreak. Overall, the highest concerns pertained to one’s children or relatives not coping well with the pandemic situation, closely followed by being unable to access medications or medical services. When asked when they expected the global situation to go back to normal, 37.2% replied ‘I have no idea’, 27.8% estimated after March 2021, 17.4% by March 2021, 14.9% by September 2020 and 2.7% by June 2020. Of the total sample, 30.4% anticipated that their own personal situation would get back to normal before the global situation resolves and 10.1% anticipated that it would take longer for their personal situation than for the global situation to get back to normal.

Figure 1.

Level of concern for potential secondary effects of the pandemic. Mean level of concern on a scale ranging from ‘0—not concerned at all’, to ‘50—neutral’ and ‘100— very concerned’. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

On average, when comparing pre-outbreak estimates and current states: sleep duration shortened (Z=−4.9, p<0.001, r=0.07), family relationships deteriorated (Z=−13.4, p<0.001, r=0.18) and weekly alcohol and cannabis consumption increased (Z=−18.1, p<0.001, r=0.24 and Z=−18.1, p<0.001, r=0.10). Specifically, 10.4% of the sample over 16 years of age increased their weekly alcohol consumption by five drinks or more.

Occupational and financial impacts

Within actively working respondents, 62.8% were working from home, 9.8% had increased work hours because of the outbreak, and 15.6% had decreased work hours. A total of 7.9% underwent a salary decrease due to the outbreak, with an overall median salary reduction of 35% (IQR=50). Of all respondents who were working in the month preceding the outbreak, 11.1% saw their employment terminated because of the outbreak.

Rates of employment termination due to the outbreak or salary loss exceeding 35% were higher in those with a family income below $C40k compared with those with higher family income (12.6%, χ2=121.0, p<0.001), in people without a university degree (23.6%) compared with those with a university degree (11.0%; χ2=74.6, p<0.001) and in people with a diagnosis of a mental disorder (16.8%) compared with those without (13.5%; χ2=4.9, p=0.027). Rates of employment termination/salary decrease were similar in women versus men (χ2=2.3, p=0.132), Caucasians versus other ethnicities (χ2=0.9, p=0.335) and people with or without physical illnesses (χ2=0.1, p=0.719).

Across the entire sample, 64.5% reported that their expenses had decreased since the start of the outbreak and 15.5% reported an increase, with a mean estimated rise in health-related expenses of 10.4%±20.3%, compared with 29.2%±38.0% for food-related expenses.

Social life

Family and other relationships

Half of the parents with underage children (54.0%) said that they or their partner were homeschooling. Most respondents estimated that the outbreak was being somewhat disruptive for the management of their work/study and family life (mean rating on a scale from ‘0—very disruptive’ to ‘50—not different from usual’ and ‘100—easier than usual’: 21.6±45.6).

The proportion of respondents interacting with their family more frequently since the start of the outbreak was significantly higher than the proportion of those who were interacting less frequently (p<0.001). The reverse pattern was found for interactions with friends (p<0.001). Among all respondents, 40.0% reported feeling more connected to their family during compared with before the outbreak, while 21.0% felt less connected. This pattern was reversed for connectedness to friends, with 36.2% reporting feeling less connected and 28.3% feeling more connected. On average, relationship ratings with both family and friends during the outbreak significantly deteriorated compared with pre-outbreak estimates (Z=−10.9, p<0.001 and Z=−28.1, p<0.001).

Social distancing

65.8% of respondents were following at least one social distancing guideline at the time of filling out the survey, with 51.6% maintaining a 2 metres distance from others, 46.3% avoiding gatherings in person, 42.5% not using public transport, 37.9% not attending public areas, 35.4% not going out of the home unless they had no choice (eg, to go to a medical appointment), 29.5% wearing a mask when leaving home and 17.9% having food/supplies delivered to their homes. A statistically significant proportion of individuals (between 57.7% and 89.0%) disengaged from some of the social distancing practices that they had initially followed since the start of the outbreak (all p<0.001).

Psychological stress

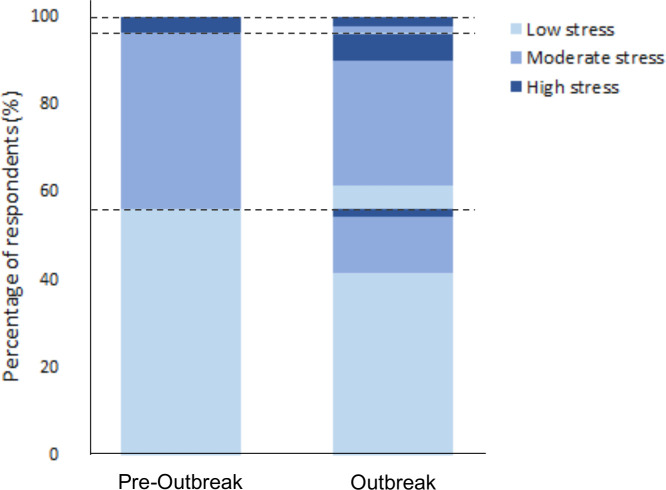

PSS scores globally increased from 12.9±6.8 before the outbreak to 14.9±8.3 during the outbreak (Z=−22.9, p<0.001, r=0.31), which reflects a transition from low to moderate stress. Rates of individuals with PSS score in the high stress range increased from 3.8% before the outbreak to 10.2% during the outbreak (figure 2). However, there was considerable heterogeneity in stress changes: a clinically meaningful increase in stress was noted in 30.3% of respondents, while 10.3% had a clinically meaningful reduction in stress.

Figure 2.

Transitions across stress levels relative to before the outbreak levels. Lasagna plot of the percentages (%) of respondents endorsing low, moderate and high stress levels (as per established severity threshold for the Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale) in the retrospective assessment of their stress levels in the month prior to the start of the pandemic (ie, Pre-outbreak) and in the past 7 days before filling out the survey (ie, Outbreak). Dashed lines indicate the transition points between the three stress severity ranges. As compared with before the outbreak, 20.8% (1063/5103) of respondents had progressed to a higher stress range during the outbreak, and 7.0% (n=355/5103) of respondents moved to a lower stress range.

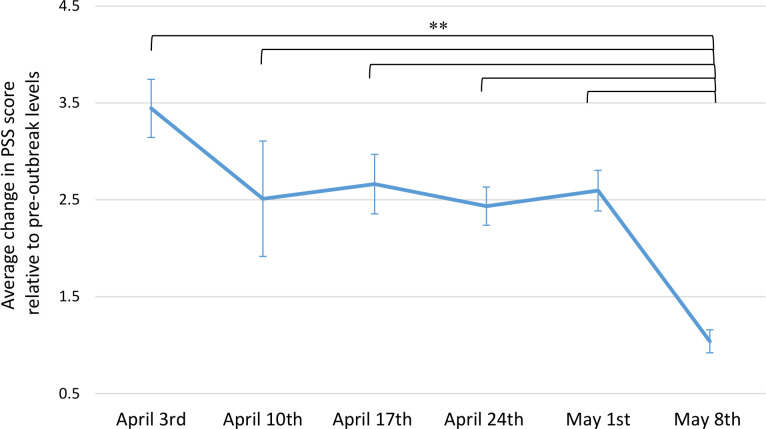

Figure 3 depicts the temporal dynamics of stress changes based on the time at which respondents filled out the survey. Over the course of the study period, there was an overall attenuation of stress worsening on PSS change scores (F(5, 5097)=20.07, p<0.001). There was a non-significant reduction in stress worsening between April 3rd and 10th, followed by a plateau, which persisted until May 8th, after which there was a significant drop (p≤0.006), compared with all preceding time periods.

Figure 3.

Patterns of stress changes across time. Average changes in score on the Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) from pre-outbreak to during the outbreak (ie, current PSS minus pre-outbreak PSS; higher scores indicating stress worsening) measured cross-sectionally across each time period of survey completion (each comprising 7 days starting on the date of the survey launch). Higher change scores reflect higher stress worsening relative to pre-outbreak stress levels. Error bars indicate the SE of the mean. Sample sizes for each 7 day time period are as follows: April 3rd: n=516, April 10th: n=135, April 17th: n=453, April 24th: n=1035, May 1st: n=936, May 8th: n=2028. **p<0.001.

In the multivariate linear regression model, the following variables were found to be significant independent factors linked to stress worsening (table 2, right panel): shorter time elapsed since the start of the outbreak, younger age, female sex, having left wing political views, work involving in-person contact with the general public, having underage children, worse COVID-19 symptoms index, shorter sleep duration, lower PSS scores before the outbreak, higher scores on the DOCS—contamination subscale and on the extraversion, conscientiousness and neuroticism scales of the Big5, lower BRCS scores, having a mental disorder diagnosis, having had more than five alcoholic drinks in the past week, worse family relationships and spending less time exercising and doing artistic activities.

Table 2.

Coefficients of the predictive model for changes in stress

| n | Single predictor variables | Full model | P value | ||||||||

| B | SE | 95.0% CI | P value | B | SE | 95.0% CI | |||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||||

| Time since outbreak start (per 7-day increase) | 5359 | −0.55 | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.07 | <0.001 | −0.18 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.002 |

| General demographics | |||||||||||

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 5357 | −0.96 | 0.01 | −0.11 | −0.09 | <0.001 | −0.52 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.04 | <0.001 |

| Male sex (vs female) | 5358 | −2.02 | 0.19 | −2.38 | −1.65 | <0.001 | −0.97 | 0.19 | −1.35 | −0.60 | <0.001 |

| Political views (vs centre or others) | |||||||||||

| Left wing | 4657 | 0.85 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 1.24 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 0.042 |

| Right wing | 4657 | 0.21 | 0.28 | −0.34 | 0.75 | 0.457 | 0.31 | 0.24 | −0.17 | 0.79 | 0.206 |

| Education: no university (vs university) | 5327 | −0.20 | 0.18 | −0.55 | 0.16 | 0.277 | −0.22 | 0.19 | −0.59 | 0.14 | 0.230 |

| Socioeconomic, occupational and living situation | |||||||||||

| Total family income (vs >$C100k) | |||||||||||

| < $C40k per year | 5009 | 0.72 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 1.33 | 0.019 | 0.30 | 0.18 | −0.05 | 0.65 | 0.094 |

| $C40 to $C100k per year | 5009 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.039 | 0.35 | 0.31 | −0.25 | 0.95 | 0.256 |

| Employment status (vs employed): | |||||||||||

| Unemployed, on leave or student | 5359 | 0.38 | 0.26 | −0.13 | 0.88 | 0.144 | 0.07 | 0.26 | −0.45 | 0.59 | 0.787 |

| Retired | 5359 | −2.37 | 0.19 | −2.75 | −2.00 | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.25 | −0.64 | 0.34 | 0.544 |

| Work contact with general public (vs not) | 5189 | 1.76 | 0.26 | 1.26 | 2.26 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 1.07 | 0.022 |

| Living in apartment or condo (vs house) | 4858 | 0.36 | 0.21 | −0.05 | 0.77 | 0.089 | −0.10 | 0.21 | −0.50 | 0.31 | 0.631 |

| Health and risks factors | |||||||||||

| C19 Symptoms index (scale from 0 to 30) | 5359 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Physical condition at risk* (vs no condition at risk) | 5342 | −0.76 | 0.17 | −1.09 | −0.42 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.18 | −0.21 | 0.50 | 0.415 |

| Sleep duration (per hour increase) | 4804 | −0.59 | 0.06 | −0.1 | −0.48 | <0.001 | −0.53 | 0.05 | −0.64 | −0.42 | <0.001 |

| Travelled abroad in last 60 days (vs no travel) | 4960 | −0.45 | 0.21 | −0.86 | −0.04 | 0.033 | −0.19 | 0.26 | −0.70 | 0.33 | 0.472 |

| Psychological domain | |||||||||||

| Preoutbreak PSS (0–40 scale) | 4920 | – | – | – | – | – | −0.44 | 0.02 | −0.47 | −0.41 | <0.001 |

| DOCS—contamination (0–20 scale) | 4717 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Big 5 Personality (2–10 scale) | |||||||||||

| Extraversion | 4680 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.001 |

| Agreeableness | 4681 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.933 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.319 |

| Conscientiousness | 4681 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.007 |

| Neuroticism | 4681 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.33 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Openness to Experiences | 4681 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.08 | 0.778 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.16 | 0.116 |

| Brief Resilient Coping Scale (4–20 scale) | 1663 | −0.17 | 0.03 | −0.23 | −0.11 | <0.001 | −0.24 | 0.03 | −0.30 | −0.17 | <0.001 |

| Mental disorder diagnosis (vs no diagnosis) | 5326 | 2.34 | 0.20 | 1.95 | 2.74 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 0.20 | 0.74 | 1.54 | <0.001 |

| Social domain | |||||||||||

| Family relationship (per 10 units; 0–100 scale) | 5028 | −0.55 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.05 | <0.001 | −0.39 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.03 | <0.001 |

| Has underage children (vs no underage children) | 5092 | 2.16 | 0.24 | 1.69 | 2.63 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 1.34 | <0.001 |

| Behavioural domain | |||||||||||

| Weekly alcohol consumption (vs no drinks) | |||||||||||

| One to five drinks | 5358 | −0.18 | 0.21 | −0.58 | 0.23 | 0.394 | 0.19 | 0.20 | −0.20 | 0.57 | 0.344 |

| More than five drinks | 5358 | 0.15 | 0.21 | −0.27 | 0.56 | 0.490 | 0.61 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 1.01 | 0.003 |

| Weekly cannabis or illicit drugs use (vs no use) | 5312 | 1.13 | 0.26 | 0.63 | 1.63 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.93 | 0.066 |

| Spent 30 min or less (vs more than 30 min): | |||||||||||

| Outdoor | 5317 | 0.91 | 0.18 | 0.56 | 1.25 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.19 | −0.32 | 0.45 | 0.736 |

| Exercising | 5295 | 1.03 | 0.17 | 0.70 | 1.37 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.87 | 0.010 |

| Following COVID-19 news | 5296 | −0.25 | 0.17 | −0.59 | 0.08 | 0.141 | −0.24 | 0.17 | −0.57 | 0.09 | 0.155 |

| Social interactions in person | 5201 | 0.14 | 0.17 | −0.20 | 0.48 | 0.406 | 0.21 | 0.16 | −0.11 | 0.53 | 0.205 |

| Social interactions virtually | 5277 | −0.46 | 0.18 | −0.80 | −0.11 | 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.17 | −0.33 | 0.34 | 0.969 |

| Doing an artistic activity | 5210 | 0.16 | 0.20 | −0.23 | 0.56 | 0.421 | 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.010 |

Coefficient parameters for multiple linear regression models including only each single predictors and baseline stress (left panel) and for the full model (right panel). B: Unstandardised coefficients (calculated per one unit for continuous variables, except for the time elapsed since the start of the outbreak, which was calculated for each 7 days, as well as age and family relationships which were calculated per 10 units). Units (for continuous variables) and reference groups (for categorical variables) are presented in parenthesis in the first column. Family relationship rated on scale from ‘0—very difficult/conflictual’, ‘50—neutral’ to ‘100—excellent’.

*Physical condition at risk for COVID-19: for example, respiratory, cardiovascular or autoimmune conditions.

DOCS, Dimensional Obsessive Compulsive Scale; LL, lower limit; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SE, standard error of B; UL, upper limit.

When assessed on their own, the following factors were found to be predictive of worse increases in stress levels (while controlling for stress levels before the outbreak) but became non-significant when controlling for confounders in the global model (table 2; left panel): lower family income (stronger relationship for the lowest income level), consuming cannabis or other drugs, spending less time outdoors and more time interacting with people virtually. Being retired, having travelled abroad in the past 60 days and having a physical condition at risk for COVID-19, were associated with lower stress worsening. Exploratory analyses stratified by biological sex are provided in supplemental materials.

Discussion

Results from this survey in 6040 respondents suggest that the financial, social and psychological correlates of the COVID-19 outbreak may interact in a complex manner and that they vary considerably across individuals. While some of our findings echo previous observations, we propose a more comprehensive integrated model of independent factors associated with worse stress responses to this pandemic.

In line with previous polls reporting that many people perceived the COVID-19 pandemic as a greater threat to the economy than to their health,19 we observed higher sense of threat related to external/global as opposed to more personal matters. Our observation of concerns about access to medical services is aligned with high rates of potential COVID-19 symptoms with low access to testing for COVID-19, a combination which may increase stress. Nearly 40% of respondents endorsed being uncertain about when the global situation would get back to normal. This contrasts with the 80% of Australians who reported moderate to extreme uncertainty about the future in a previous survey done in March and April 2020.11 This difference could stem from temporal, cultural or public health variants.

Previous studies indicated that lower income is associated to higher incidences of COVID-19 infections,20 but such economic factors are also affecting many collateral effects of the pandemic. Consistent with Canadian rates of employment that plummeted by about 11% from February to April 2020,21 but lower than the 50% worldwide job losses anticipated by the UN labor agency,22 11% of our respondents lost their job because of the outbreak and an additional 8% underwent salary cuts, with a non-trivial median reduction in salary of 35%. Low income and the lack of a university degree were found to be major risk factors for adverse work and salary outcomes, a phenomenon that may further widen economic disparities. Similarly, reports in the USA showed that 40% of people earning US$40k or less lost their jobs due to the COVID-19 outbreak and that most of those who kept their job had a university degree.23 These figures are however much lower than those observed in developing countries, with about two-thirds of respondents to a survey circulated in Vietnam reporting decreased income.24 Importantly, the current study is, to our knowledge, the first one to identify having a mental disorder as a risk factor for employment termination during the outbreak. The psychological impacts of unemployment are likely to further worsen mental health in these individuals, and they may be at higher risks for subsequent unemployment.25 Therefore, this subgroup may face additional challenges not only to cope with the occupational and financial consequences of the pandemic but also to find work after deconfinement, which highlights potential needs for targeted governmental relief packages and supporting programmes to find work. Increased expenses since the start of the outbreak seemed to be most prominently related to food. Although concerns about lacking food were rather mild in the current sample, some respondents may have been stocking up in the context of supply disruption and/or facing increases in pricing for food.26

In line with early COVID-19 reports from China describing major reductions in social contacts beyond the household,27 we observed increased interactions with family and decreased interactions with friends, which probably reflect social distancing. This change was accompanied by consistent changes in feelings of connectedness and, paradoxically, by a worsening in relationships quality. Together with previous observations of increased family violence during the pandemic,28 this stresses the need to better understand how close proximity in the context of confinement may create family tensions. Only 66% of respondents were following at least one social distancing guideline, a percentage similar to previously reported rates in a previous Canadian poll.29 Although the state of emergency still prevailed at the time of the survey, about 60%–90% of respondents had been phasing out their social distancing practices. This raises considerable concerns since even a 20% increase in adherence to social distancing can contribute to slow the spread of COVID-19.30

We found a significant increase in stress co-occurring with the outbreak, with 30% of individuals undergoing clinically meaningful stress worsening. This echoes findings from a recent systematic review31 and is consistent with rates of moderate to severe stress reaching 20%–27% in Asia, Europe and Australia.7 11 32–36 As anticipated, more acute stress reactions were observed in the earlier phases of the outbreak, with a sharp drop shortly after the mortality peak in Canada was announced. These preliminary observations suggest that although the degree of stress worsening during the outbreak may have been phasing out for many individuals, 2 months after the pandemic declaration, stress levels were not fully back to pre-outbreak levels. This supports the need for the development/promotion of self-help tools for stress management.

Having a current diagnosis of a mental disorder was found to be the strongest independent factor linked to stress worsening, a finding consistent with previous observations about pre-existing psychiatric conditions.7 11 32–35 This stresses the importance of further investigations in this group who may require more intensive stress management resources. Poorer coping skills and personality traits loading heavily on neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness were also associated with worse increases in stress. High neuroticism has previously been linked to maladaptive stress coping strategies.37 While personalities loading on conscientiousness are usually well-organised, goal-directed and more effective in dealing with stress, the uncertainty associated with this unprecedented outbreak may prevent them from relying on their usual coping strategies, leading to heightened stress. Since extraversion is characterised by a tendency to be active and sociable, social distancing measures probably contributed to worse stress responses in extraverted individuals. Accordingly, a Brazilian COVID-19 survey showed that higher extraversion was associated with lower engagement in social distancing practices, likely reflecting how challenging it is for extraverted individuals to reduce their social proximity.38 In line with our finding of an association between left-wing views and stress worsening, a recent Gallup poll in the USA39 found that liberals (as compared with conservatives) were more likely to worry about worst-case outcomes of the pandemic. Humans are known to outsource their understanding of the world to their political ingroup.40 The politicisation of the crisis and associated media bias (with risk-preventive, pro-lockdown perspectives in the liberal media and the conservative media appearing to take the crisis less seriously) is one possible explanation for worse pandemic-related distress in liberals.

Our results confirm that several factors previously linked to stress, such as female sex, younger age, having children, and having symptoms that could be linked to COVID-197 11 12 36 41–43 independently contribute to stress worsening. While previous reports highlighted high risks in healthcare workers,12 44 45 our findings suggest that this extends to other types of workers physically interacting with the public (e.g., people working in public transport, grocery stores). Importantly, the current study also identified some modifiable factors that were associated with lower stress responses. For instance, protecting a sufficient period for sleep, minimising alcohol and drug consumption, promoting better family relationships, exercising and doing artistic activities may be helpful. Sleep disturbances often emerge in response to external stressors and can further worsen physiological and psychological stress responses.46 Since sleep is thought to contribute to emotional regulation,47 attenuating the adverse effects of the pandemic on sleep may enable better coping resources. In addition to the benefits of exercise on sleep, about 30 min of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise three times weekly may also boost mood and reduce psychological distress.48 Planning family activities that may help alleviate tensions and foster more positive relations, as well as creating some time and space for individuals to offset the challenges posed by sustained family proximity may also be relevant to manage stress. Appropriate home-schooling support as well as better work adaptation for parents may also be required. Increased access to testing is likely to have the collateral effect of attenuating stress levels. Further investigations may be required to better understand if limiting the time spent on virtual interactions with people may also play a protective role against stress. From the current study, it is not possible to differentiate virtual interactions that may be related to work from those related to family/friend contacts. Also, the association with increased stress worsening and virtual communications may be in part driven by individuals seeking more frequent virtual contacts to alleviate their stress, but the cross-sectional nature of the current analyses does not allow to determine whether this is an effective strategy or not. There was also considerable sex differences in factors associated with stress, which may call for the development of sex-specific interventions. Furthermore, although this was not investigated in the current report, other studies indicated that preventative measures and personal protective equipment may facilitate lower stress in relation to the pandemic.49 50 The potential of several lines of psychological interventions to mitigate the mental health impacts of the pandemic is also rapidly being highlighted.51

The study has several important limitations. The observational and cross-sectional nature of this study precludes any causality inference and recall bias may have affected retrospective estimates of pre-outbreak metrics. Representativeness (e.g., age distribution skewed towards middle age, higher rates of women, highly educated individuals with high-income status, which are not representative of the global Canadian population) and generalisability are limited by the sample selection, dissemination strategy and volunteer bias; although our demographic characteristics are consistent with other published surveys. The length and online nature of the survey may have prevented some individuals from completing it. Although our multivariate model corrected for this, data collection spanned over a month, a period during which we did observe dynamic changes in stress responses. This study also has several strengths, such as a relatively large sample size, the comprehensive set of factors assessed and its launch in the acute phase of the outbreak.

Conclusion

Baseline data in 6040 respondents who shared their experiences in the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted adverse financial, social and psychological outcomes. Our preliminary findings start to draw a comprehensive model integrating multiple independent factors of the stress responses to this pandemic. Modifiable risk factors identified could inform the development of targeted interventions and support. Populations at risk that should be targeted include: people with pre-existing mental disorders, parents of underage children, people with low income, workers interacting with the general public, people with potential COVID-19 symptoms, and those with sleep disruptions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the participants who gave their time to fill out this extensive survey during a difficult period. The authors also extend their gratitude to: the individuals who provided their comments on the survey content and format during the development stage; to Rachel Théoret, Samantha Kenny, Rebecca Burdayron and Christopher Kalogeropoulos for their help with preparing some documents for some of the ethics applications; to the ethics boards who rapidly and diligently provided insights on this project to enable a timely launch; to the organizations who helped circulate the survey in their networks, including Ottawa Public Health, and to NIVA inc, for their advice on distribution strategies. The authors thank the Clinical Investigation Unit at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health for assistance with recruiting participants.

Footnotes

Contributors: RR, TK and JE were involved in project administration and participants’ recruitment as site primary investigators. RR, MS, AN and TK were additionally involved in the following: analyses of data and drafting of the manuscript. RR, MS, JE, ESo, M-HP, AD, SPLV, LQ, KD, AN, JP, RB, ESp, RG, BY, CR, WAG, MG, AB, RS and TK were involved in the following: study conception and design, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for the accuracy and important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. RR, MS, JE, ESo, M-HP, AD, SPLV, LQ, KD, AN, JP, RB, ESp, RG, BY, CR, WAG, MG, AB, RS and TK are accountable for all aspect of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Clinical Trials Ontario—Qualified Research Ethics Board via the Ottawa Health Science Network (Protocol number 2131).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Proposals to access data from this study can be submitted to the corresponding author and may be made available upon data sharing agreement.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus Infections-More than just the common cold. JAMA 2020;323:707–8. 10.1001/jama.2020.0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation [Internet]. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation, 2020. Available: https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=CjwKCAjw8pH3BRAXEiwA1pvMsXDoze2QLDa_4WTtExJMku1J3er_GLk-MjRPeOb4_6_ECkdivray6hoCh-oQAvD_BwE [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 3.Horesh D, Brown AD. Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: a call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2020;12:331–5. 10.1037/tra0000592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, Wang Y, Xue J, et al. . The impact of covid-19 epidemic Declaration on psychological consequences: a study on active weibo users. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2032 10.3390/ijerph17062032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lima CKT, Carvalho PMdeM, Lima IdeAAS, et al. . The emotional impact of coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Res 2020;287:112915 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson B, Pettitt A, Flannery J, et al. . Rapid assessment of psychological and epidemiological predictors of COVID-19 concern, financial strain, and health-related behavior change in a large online sample. PsyArXiv Prepr 2020. https://psyarxiv.com/jftze [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, et al. . A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr 2020;33:e100213. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. . Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1729 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang C, Chudzicka-Czupała A, Grabowski D, et al. . The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:901. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsing A, Zhang JS, Peng K, et al. . A rapid assessment of psychological distress and well-being: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Shelter-in-Place. SSRN Electron J 2020. 10.2139/ssrn.3578809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newby JM, O’Moore K, Tang S, et al. . Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. PLoS One 2020;15:e0236562 10.1371/journal.pone.0236562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Limcaoco RSG, Mateos EM, Fernandez JM, et al. . Anxiety, worry and perceived stress in the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic, March 2020. Preliminary results. medRxiv 2020. http://medrxiv.org/content/early/2020/04/06/2020.04.03.20043992.abstract 10.1101/2020.04.03.20043992 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Zhao N. Chinese mental health burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;51:102052. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, et al. . The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit 2020;26:e923549. 10.12659/MSM.923549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of Internet E-Surveys (cherries). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eskildsen A, Dalgaard VL, Nielsen KJ, et al. . Cross-Cultural adaptation and validation of the Danish consensus version of the 10-item perceived stress scale. Scand J Work Environ Health 2015;41:486–90. 10.5271/sjweh.3510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Government of Canada Epidemiological summary of COVID-19 cases in Canada, 2020. Available: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html#a4

- 19.Lacey N. Public divided on whether isolation, travel bans prevent COVID-19 spread; border closures become more acceptable, 2020. Available: https://www.ipsos.com/en/public-divided-whether-isolation-travel-bans-prevent-covid-19-spread-border-closures-become-more

- 20.Baena-Díez JM, Barroso M, Cordeiro-Coelho SI, et al. . Impact of COVID-19 outbreak by income: hitting hardest the most deprived. J Public Health 2020;42:698–703. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statistics Canada Canadian economic Dashboard and COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/71-607-x2020009-eng.htm

- 22.UN News Nearly half of global workforce at risk as job losses increase due to COVID-19: UN labour agency, 2020. Available: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1062792

- 23.Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2018, 2020. Available: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/default.htm

- 24.Dang AK, Le XTT, Le HT, et al. . Evidence of COVID-19 impacts on occupations during the first Vietnamese national Lockdown. Ann Glob Health 2020;86:112. 10.5334/aogh.2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olesen SC, Butterworth P, Leach LS, et al. . Mental health affects future employment as job loss affects mental health: findings from a longitudinal population study. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:144. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobbs JE. Food supply chains during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Can J Agric Econ Can d’agroeconomie 2020. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Litvinova M, Liang Y, et al. . Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science 2020;368:1481–6. 10.1126/science.abb8001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 2020;146:e20200982. 10.1542/peds.2020-0982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polls – research CO, 2020. Available: https://researchco.ca/polls/

- 30.Ottawa COVID19 projections, 2020. Available: https://613covid.ca/#

- 31.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. . Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2020;277:55–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, et al. . The enemy who sealed the world: effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med 2020;75:12–20. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, et al. . A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the covid-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3165. 10.3390/ijerph17093165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davico C, Ghiggia A, Marcotulli D, et al. . Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults and their children in Italy. SSRN Journal 2020. 10.2139/ssrn.3576933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreira PS, Ferreira S, Couto B, et al. . Protective elements of mental health status during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Portuguese population. medRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, et al. . COVID-19 pandemic and Lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:790. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kendler KS, Kuhn J, Prescott CA. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:631–6. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carvalho LdeF, Pianowski G, Gonçalves AP. Personality differences and COVID-19: are extroversion and conscientiousness personality traits associated with engagement with containment measures? Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2020;42:179–84. 10.1590/2237-6089-2020-0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarthy JUS. Coronavirus concerns surge, government trust slides, 2020. Available: https://news.gallup.com/poll/295505/coronavirus-worries-surge.aspx?utm_source=alert&utm_medium=email&utm_content=morelink&utm_campaign=syndicat

- 40.Veissière SPL, Constant A, Ramstead MJD, et al. . Thinking through other minds: a variational approach to cognition and culture. Behav Brain Sci 2019;43:e90. 10.1017/S0140525X19001213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, et al. . Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl 2020;104699:104699. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez-Rey R, Garrido-Hernansaiz H, Collado S. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Front Psychol 2020;11:1540. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, et al. . Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord 2020;277:379–91. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, et al. . Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One 2020;15:e0237301. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mo Y, Deng L, Zhang L, et al. . Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J Nurs Manag 2020;28:1002–9. 10.1111/jonm.13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Åkerstedt T. Psychosocial stress and impaired sleep. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:493–501. 10.5271/sjweh.1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gruber R, Cassoff J. The interplay between sleep and emotion regulation: conceptual framework empirical evidence and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014;16:500. 10.1007/s11920-014-0500-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paolucci EM, Loukov D, Bowdish DME, et al. . Exercise reduces depression and inflammation but intensity matters. Biol Psychol 2018;133:79–84. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. . A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:40–8. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, et al. . Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:84–92. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.CS H, Chee C, Ho R. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2020;49:155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043805supp001.pdf (338.2KB, pdf)