Abstract

Hydrogen can serve as an electron donor for chemolithotrophic acidophiles, especially in the deep terrestrial subsurface and geothermal ecosystems. Nevertheless, the current knowledge of hydrogen utilization by mesophilic acidophiles is minimal. A multi-omics analysis was applied on Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans growing on hydrogen, and a respiratory model was proposed. In the model, [NiFe] hydrogenases oxidize hydrogen to two protons and two electrons. The electrons are used to reduce membrane-soluble ubiquinone to ubiquinol. Genetically associated iron-sulfur proteins mediate electron relay from the hydrogenases to the ubiquinone pool. Under aerobic conditions, reduced ubiquinol transfers electrons to either cytochrome aa3 oxidase via cytochrome bc1 complex and cytochrome c4 or the alternate directly to cytochrome bd oxidase, resulting in proton efflux and reduction of oxygen. Under anaerobic conditions, reduced ubiquinol transfers electrons to outer membrane cytochrome c (ferrireductase) via cytochrome bc1 complex and a cascade of electron transporters (cytochrome c4, cytochrome c552, rusticyanin, and high potential iron-sulfur protein), resulting in proton efflux and reduction of ferric iron. The proton gradient generated by hydrogen oxidation maintains the membrane potential and allows the generation of ATP and NADH. These results further clarify the role of extremophiles in biogeochemical processes and their impact on the composition of the deep terrestrial subsurface.

Keywords: Acidithiobacillus, extremophiles, ferric iron reduction, hydrogen metabolism, multi-omics, oxygen reduction

Introduction

Microbial life in the deep terrestrial subsurface is a subject of considerable interest, as geochemical processes provide a source of energy for the metabolism of chemolithotrophic microbial communities. While the deep continental subsurface is estimated to contain up to 20% of the Earth’s total biomass (McMahon and Parnell, 2014), this biosphere is one of the least understood ecosystems because of the methodological limitations of studying niches dispersed in solid matrixes (Amils, 2015). Understanding the nature of deep terrestrial biospheres and how these are maintained is fundamental to deciphering the origin of life not only on Earth, but potentially on other planets and moons (Chapelle et al., 2002; Bauermeister et al., 2014). In addition, microbial processes impact the geochemistry of deep repositories and groundwater reservoirs, affecting the feasibility of resource extraction. Since raw materials, such as metal ores, located close to Earth’s surface are becoming depleted, the exploration of deep-buried (>1 km) mineral deposits is currently focused on the deeper subsurface (Johnson, 2015). Subsurface life is dependent on buried organic matter and geogenic reduced compounds such as hydrogen gas (H2) (Stevens, 1997; Bagnoud et al., 2016). Hydrogen in the subsurface can be generated by the process of hydration (serpentinization) of an igneous rock with a very low silica content and rich in minerals (ultramafic rock) (Mayhew et al., 2013) and the radiolysis of water (Blair et al., 2007). In addition, many anaerobic bacteria can exploit organic compounds to produce H2 by reducing protons (Teng et al., 2019). However, the importance of H2 as an electron donor for acidophiles in the subsurface and geothermal springs as well as deep-sea hydrothermal vents remains unknown. Also, most of the information that has been published on acidophilic life in the subterranean environments has come from the research of abandoned deep mines and caves (Johnson, 2012). Recently, drill cores taken from the largest known massive sulfide deposit have confirmed the presence of members of hydrogen, methane, iron and sulfur oxidizers, and sulfate-reducers many of which are acidophilic (Puente-Sánchez et al., 2014, 2018).

Four distinct bacterial phyla containing a number of acidophiles (Actinobacteriota, Acidobacteriota, Chloroflexota, and Verrucomicrobiota) have been experimentally shown to utilize atmospheric H2 by the [NiFe] group 2a hydrogenase (Islam et al., 2020). To date, autotrophic growth by dissimilatory H2 oxidation has been reported only for several acidophiles. Among the acidophilic archaea, members of the genera Sulfolobus, Acidianus, and Metallosphaera were found to be able to grow aerobically on H2 (Huber et al., 1992). Acidophilic bacteria growing aerobically on H2 include obligate autotrophs Acidithiobacillus spp. (iron/sulfur-oxidizing At. ferrooxidans, At. ferridurans, At. ferrianus, and sulfur-oxidizing At. caldus), iron/sulfur-oxidizing facultative autotrophs Sulfobacillus spp. (Sb. acidophilus, Sb. benefaciens, and Sb. thermosulfidooxidans), and iron-oxidizing facultative autotroph Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans (Drobner et al., 1990; Ohmura et al., 2002; Hedrich and Johnson, 2013; Norris et al., 2020). Of these, At. ferrooxidans, At. ferridurans, At. ferrianus, Sb. thermosulfidooxidans, and Sb. benefaciens have been reported to grow anaerobically using H2 as an electron donor and Fe3+ as an electron acceptor (Ohmura et al., 2002; Hedrich and Johnson, 2013; Norris et al., 2020). Although genomic studies have demonstrated the presence of genes encoding different hydrogenases in many acidophiles, their presence does not necessarily mean that these bacteria grow by oxidizing H2, as some hydrogenases may produce H2 (Valdés et al., 2008). Hydrogen metabolism can be divided into the respiratory oxidation of H2 to H+ (uptake) linked to quinone reduction in membrane-bound respiratory electron transfer chain, and H2 production by reducing H+ to H2 in non-energy conserving anaerobic system with a low electron transfer potential. The redox reactions are catalyzed by metalloenzymes (hydrogenases) (Lubitz et al., 2014). The transport of electrons to or from H2 is associated with H+ translocation across the membrane, which results in energy conservation in the form of proton motive force (PMF). Hydrogenases consist of three phylogenetically distinct classes, i.e., [NiFe], [FeFe], and [Fe] hydrogenases (Vignais and Billoud, 2007). The reduction potentials of the active site and prosthetic groups of [NiFe] hydrogenase from Allochromatium vinosum were determined to range from –390 to –30 mV (Armstrong and Albracht, 2005). The At. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270T genome has been shown to encode four different types of [NiFe] hydrogenases: (i) membrane-bound respiratory [NiFe] group 1 hydrogenase, (ii) cyanobacterial uptake and cytoplasmic [NiFe] group 2 hydrogenase, (iii) bidirectional hetero-multimeric cytoplasmic [NiFe] group 3 hydrogenase, (iv) H2-evolving, energy-conserving, membrane-associated [NiFe] group 4 hydrogenase (Valdés et al., 2008). Even though H2 as an electron donor has several advantages for acidophiles compared to other inorganic substrates, including avoiding generating or consuming acidity and Fe3+ precipitation, few physiological studies have been reported (Fischer et al., 1996; Ohmura et al., 2002; Islam et al., 2020), and no detailed information on H2 uptake and metabolic pathways in acidophilic mesophiles is available. Recently, the energy metabolism pathways for autotrophic growth on H2 in thermoacidophilic methanotrophs of the genus Methylacidiphilum and Methylacidimicrobium (both Verrucomicrobia) from extremely acidic geothermal systems have been proposed (Carere et al., 2017; Mohammadi et al., 2019; Schmitz et al., 2020).

At. ferrooxidans contains three types of membrane-bound terminal oxidases, including an aa3 cytochrome c oxidase and cytochrome ubiquinol oxidases of the bd and bo3 type. The level of their expression was found to be dependent on whether ferrous iron or zero-valent sulfur was provided as electron donor (Quatrini et al., 2009). The aa3 cytochrome c oxidase that is part of the rus operon was shown to be induced when the At. ferrooxidans cells oxidized Fe2+ aerobically, while the bd and bo3 cytochrome ubiquinol oxidases were induced during aerobic S0 oxidation. Although optical spectra of At. ferrooxidans cells grown with S0 showed higher intensity of peaks with an absorption maximum at 613 nm, indicating the ba3 type cytochrome c oxidase (Brasseur et al., 2004), the corresponding genes which encode this complex have not been found in the At. ferrooxidans genomes sequenced to date. The mechanism of respiratory Fe3+ reduction in Acidithiobacillus spp. has not been fully elucidated. It has been assumed that Fe3+ reduction occurs outside of the inner membrane due to the insolubility of Fe3+ above pH ∼2.5, and the toxicity of elevated concentrations of ferrous iron (Corbett and Ingledew, 1987). However, no respiratory Fe3+ reductase has been confirmed biochemically in Acidithiobacillus spp. to date. Tetrathionate hydrolase and arsenical resistance protein, both of which were previously suggested to mediate Fe3+ reduction in At. ferrooxidans (Sugio et al., 2009; Mo et al., 2011), were not detected during anaerobic oxidation of S0 coupled to Fe3+ reduction (Kucera et al., 2012, 2016b; Osorio et al., 2013), and also in this study. It follows, therefore, that respiratory Fe3+ reduction is mediated by another enzyme(s). An indirect mechanism has also been proposed involving the non-enzymatic reduction of Fe3+ by H2S generated by a disproportionation of S0 which is mediated by sulfur reductase during anaerobic growth with elemental sulfur (Osorio et al., 2013). However, this mechanism is not relevant during growth with H2. As early as the 1980s, the same cytochromes and electron transporters involved in the aerobic Fe2+ oxidation were suggested to mediate anaerobic Fe3+ reduction, but in reverse (Corbett and Ingledew, 1987). This hypothesis was subsequently confirmed by several transcriptomic and proteomic approaches in At. ferrooxidans grew anaerobically on S0 coupled to Fe3+ reduction (Kucera et al., 2012, 2016a,b; Osorio et al., 2013; Norris et al., 2018). The main proposed multiple mechanisms included products of the rus operon such as the outer membrane cytochrome c (Cyc2, expected to function as a terminal Fe3+ reductase), the periplasmic electron transporters rusticyanin and cytochrome c552 (Cyc1), as well as products of the petI and petII operons such as the periplasmic high potential iron-sulfur protein Hip, cytochromes c4 (CycA1 and CycA2), and the inner-membrane cytochrome bc1 complexes I and II (PetA1B1C1 and PetA2B2C2), with the UQ/UQH2 pool providing a connection to the electron donor oxidation (Kucera et al., 2016a). In addition, the loss of the ability to anaerobically reduce Fe3+ was observed in At. ferrooxidans subcultures subsequently passaged aerobically on elemental sulfur (Kucera et al., 2016b). Further analysis revealed dramatic changes within rus, petI, and petII operons products, resulting in a decrease in Cyc2 and Rus at both the RNA and protein levels, and down-regulation of cyc1, cycA1, petA1, and cycA2 (Kucera et al., 2016b). The loss of the ability to anaerobically reduce Fe3+ was also observed in At. ferridurans, which was caused by salt stress-induced insertional inactivation of the rus operon (Bonnefoy et al., 2018). This evidence pointed to the essential role of some gene(s) encoded by the rus operon in the mechanism of anaerobic respiratory Fe3+ reduction in iron-oxidizing acidithiobacilli.

In this study, a multi-omics approach, involving transcriptomics and proteomics, was used to reveal the respiratory pathways in the mesophilic acidophile At. ferrooxidans oxidizing H2 as the sole electron donor under both aerobic (coupled to oxygen reduction) and anaerobic (coupled to ferric iron reduction) conditions.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

At. ferrooxidans strain CCM 4253 (GCA_003233765.1) was plated onto a selective overlay medium containing ferrous sulfate (Johnson and Hallberg, 2007) and incubated aerobically at 30°C for 10 days, after which a single colony was transferred into a sterile medium containing basal salts and trace elements (Osorio et al., 2013), adjusted with sulfuric acid to pH 1.9. The re-purified culture was grown both aerobically and anaerobically with H2 as sole electron donor in 1 L shake flasks containing 500 mL basal salts medium placed in 2.5 L sealed jars (Oxoid, United Kingdom), where the atmosphere was enriched with both H2 and CO2, as described elsewhere (Hedrich and Johnson, 2013). In brief, 1.3 g sodium bicarbonate, 0.3 g sodium borohydride and 0.15 g citric acid was put into 20 mL universal bottles, 10 mL of water added, and the effervescing mixture placed into the jars, which were sealed as rapidly as possible. This generated an atmosphere containing up to 31.7 mmoles of H2 and 15.5 mmoles of CO2 (some of the nascent gases were invariably lost during sealing of the jars). The sealed jars were maintained at 30°C and agitated. Initially At. ferrooxidans was adapted to aerobic growth on H2 (where the sealed jars contained 23.0 mmoles of O2), and subsequently to anaerobic conditions where Fe3+ (25 mmoles; added from a 1 M filter-sterilized stock solution of ferric sulfate, pH 1.5) replaced oxygen as terminal electron acceptor. For the latter, O2 was removed by placing an AnaeroGenTM sachet (Oxoid) into each jar. This caused the O2 present to be reduced to CO2, producing an atmosphere containing up to 38.5 mmoles of CO2. Ferrous iron production was monitored using the ferrozine colorimetric method (Stookey, 1970). After almost all Fe3+ was reduced, the cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting pellets were washed with sterile dilute sulfuric acid (pH 1.7), frozen and stored at −70°C until further processing. Control triplicate aerobic cultures were grown in shake flasks (500 ml in 1 L conical flasks) in the basal salts medium as described above, containing 0.05 mmoles Fe2+, and supplemented with 31.25 mmoles magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, to compensate the osmotic stress caused by including ferric sulfate in anaerobic cultures. When the biomass densities reached 109 cells mL–1, the cultures were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, pellets frozen and stored at −70°C. Cells were enumerated using a Thoma counting chamber and a Leitz Wetzlar 766200 (Germany) phase-contrast microscope.

RNA Sequencing and Transcript Analysis

Three biological replicates were prepared for the aerobic and anaerobic H2-grown At. ferrooxidans. The total RNA was extracted with a TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) and was treated with a TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion) to remove the contaminating DNA. The quality and quantity of RNA were assessed with a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and by Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent). The cDNA libraries were constructed using the ScriptSeqTM Complete Kits (Bacteria) (Illumina), including Ribo-ZeroTM technology for ribosomal RNA removing and ScriptSeq v2 RNA-Seq Library Preparation Kit. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina MiSeq platform with MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (500 cycles), which generated 250 bp paired-end reads. Quality control of reads was performed using R package ShortRead (Morgan et al., 2009). Subsequently, reads were aligned to the genome sequence of the At. ferrooxidans CCM 4253 (GCA_003233765.1) using the software BBmap (Bushnell et al., 2017). R package DeSeq2 was used for differential analysis of count data (Love et al., 2014). Transcripts with |log2 fold change| > 1 and q < 0.05 (FDR-adjusted P-values) were considered as differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

MS Proteomics and Protein Identification

Three biological replicates for each condition were used for proteomic analyses. 200 μl of lysis buffer containing 8 M urea and 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was added to each bacterial pellet of aerobically and anaerobically grown cells. The suspensions were homogenized by needle sonication (90 × 0.5 s pulses at 50 W; HD 2200, Bandelin) and then incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatants (protein lysates) were stored at −80°C. The protein concentration was determined by RC-DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). One hundred μg of protein lysates were digested with trypsin (Promega; 1:30 trypsin:protein ratio) on 30 kDa Microcon columns (Merck Millipore) as previously described (Janacova et al., 2020). The eluted peptides were desalted on a C18 column (MicroSpin, Harvard Apparatus) (Bouchal et al., 2009), dried and stored at −80°C. Prior to LC-MS analysis, the peptides were transferred into LC-MS vials using acidic extraction and concentrated in a vacuum concentrator to 25 μL (Hafidh et al., 2018). The peptide concentration was assessed using LC-UV analysis on the RSLCnano system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) based on the area under the UV chromatogram (214 nm) using an external calibration curve using in-house MEC cell line lysate digest (from 50 to 2,000 ng per injection). One to two microliters of concentrated sample were spiked in with 2 μL of 10-fold diluted iRT peptide mix (Biognosys) for data dependent acquisition (DDA), or data independent acquisition (DIA), respectively. The sample volume was adjusted to 10 μL total volume by the addition of 0.5% (v/v) formic acid and 0.001% (w/v) poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG 20,000) (Stejskal et al., 2013). Then, 5 μL of the 10-, or 5-fold diluted samples corresponding to approximately 0.5, or 1.0 μg of peptide material was injected onto a column for DDA, or DIA analyses, respectively. LC-MS/MS analyses of diluted peptide mixtures with spiked in iRT peptides were performed using an RSLCnano System coupled to a TOF Impact II mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics). Before LC separation, the samples were concentrated online on the trap column (100 μm × 20 mm) filled with 5 μm, 100 Å, C18 sorbent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham). The trapping and analytical columns were equilibrated before injecting the sample into the sample loop. The peptides were separated using an Acclaim Pepmap100 C18 column (3 μm particles, 100 Å, 75 μm × 500 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 300 nL min–1 with the following LC gradient program, where the mobile phase A was 0.1% (v/v) FA in water and mobile phase B was 0.1% (v/v) FA in 80% (v/v) acetonitrile: the proportion of mobile phase B was increased from the initial value of 1–56% over 120 min, raised to 90% between 120 and 130 min, and then held at 90% for 10 min. The analytical column’s outlet was directly connected to a CaptiveSpray nanoBooster ion source (Bruker Daltonics). Each sample was analyzed in DDA mode for spectral library generation, and DIA mode for DIA-based quantification. In DDA mode, the NanoBooster was filled with acetonitrile, and then MS and MS/MS spectra were acquired with a 3 s cycle time. The mass range was set to 150–2,200 m/z, and precursors were selected from 300 to 2,000 m/z. The acquisition speeds of the MS and MS/MS scans were 2 and 4–16 Hz, respectively, with the precise speed for MS/MS acquisitions being based on precursor intensity. For protein quantification in all samples in DIA mode, the NanoBooster was bypassed. MS and MS/MS data were acquired by performing survey MS scan followed by 64 MS/MS scans variable SWATH windows (Collins et al., 2017) between 400 and 1,200 m/z (1 m/z overlap). The acquisition speed of MS/MS scans was 20 Hz, the speed of MS/MS spectrum acquisition depended on precursor intensity, and the cycle time did not exceed 3.5 s. To create a spectral library, DDA data were searched in MaxQuant 1.5.8.3.1 against the genome sequence of the At. ferrooxidans CCM 4253 (GCA_003233765.1) complemented with the iRT protein database (Biognosys) and the internal database of common protein contaminants in Andromeda using the default settings for a Bruker qTOF-type mass spectrometer. In these searches, trypsin was the designated enzyme (cleaving polypeptides on the carboxyl side of lysine or arginine except when either is followed by proline), the maximum missed cleavage sites were set to 2, and the taxonomy was set as At. ferrooxidans. The PSM, protein, and site FDR thresholds were all set to 0.01 based on decoy database search. The precursor and fragment mass tolerances were set to 0.07 Da/0.006 Da (first search/main search) and 40 ppm, respectively. The permitted dynamic modifications were Oxidation (M); Acetyl (Protein N-terminus), and the only permitted static (fixed) modification was Carbamidomethyl (C). The spectral library was created in Spectronaut 11.0 (Biognosys), based on MaxQuant search results for all DDA analyses; it contained 14,331 precursors representing 11,409 peptides (of these, 11,051 were proteotypic), 1,620 protein groups and 1,658 proteins. The spectral library file is available in the PRIDE dataset. Quantitative information was extracted from the DIA data using Spectronaut 11.0 for all corresponding proteins/peptides/transitions and all conditions, using an algorithm implemented in Spectronaut. Only proteotypic peptides detected with significant confidence (q < 0.01) at least three times across all DIA runs were included in the final dataset; this was ensured by using the “q-value 0.5 percentile” setting in Spectronaut. Local data normalization was applied between runs. Proteins with |log2 fold change| > 0.58 and q < 0.05 (calculated using Student’s t-test as implemented in Spectronaut) were considered as differentially expressed proteins (DEPs).

Results and Discussion

Global Multi-Omics Data

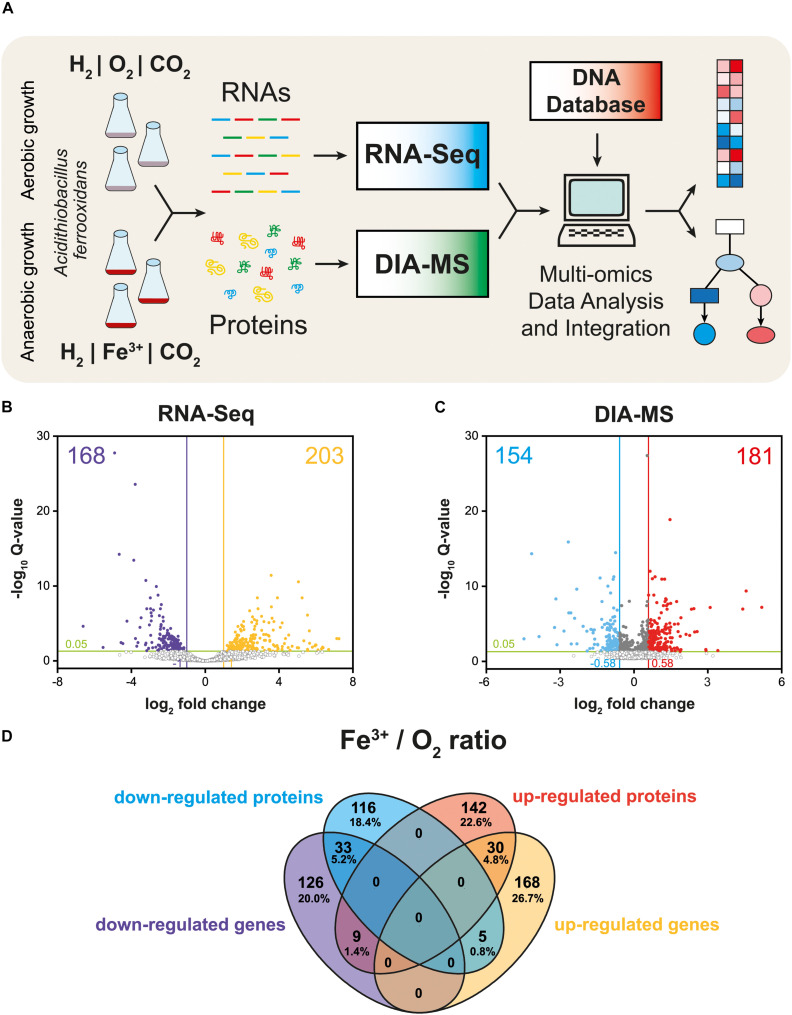

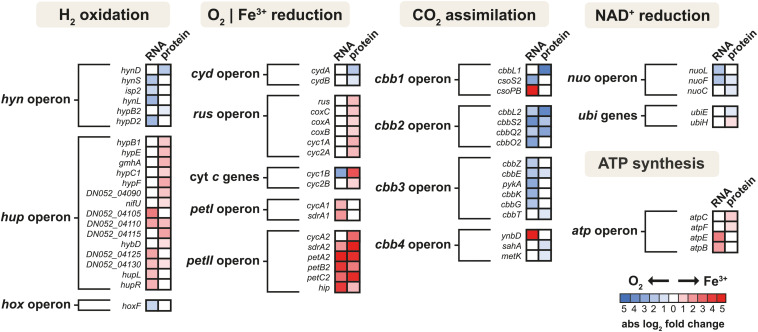

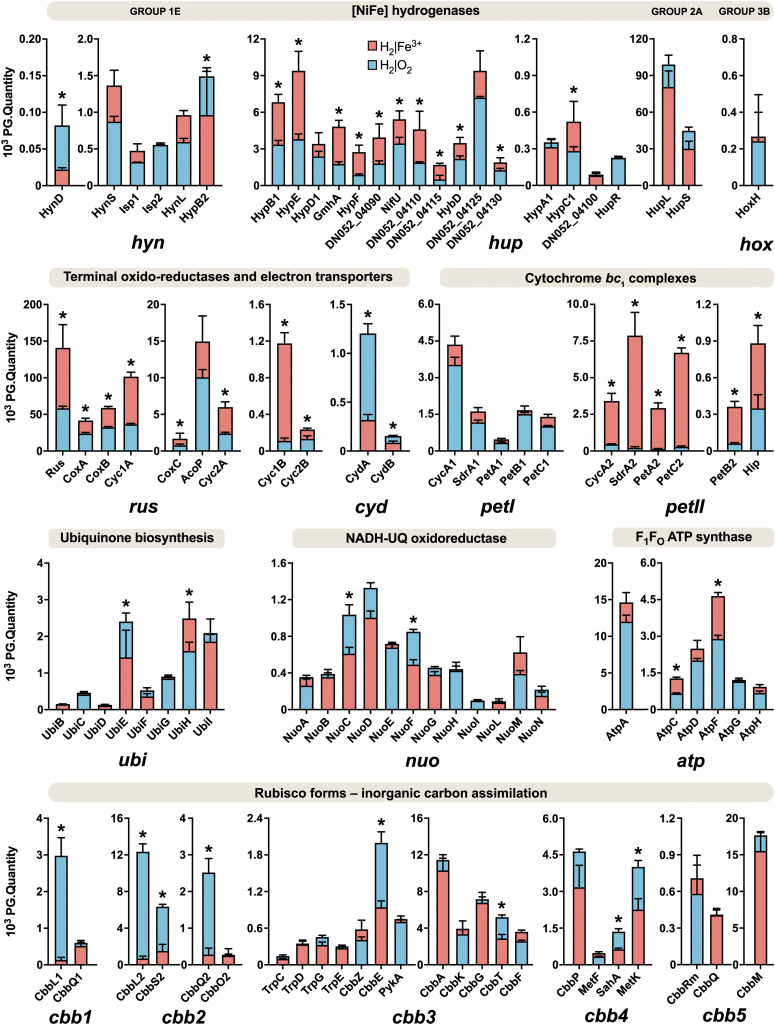

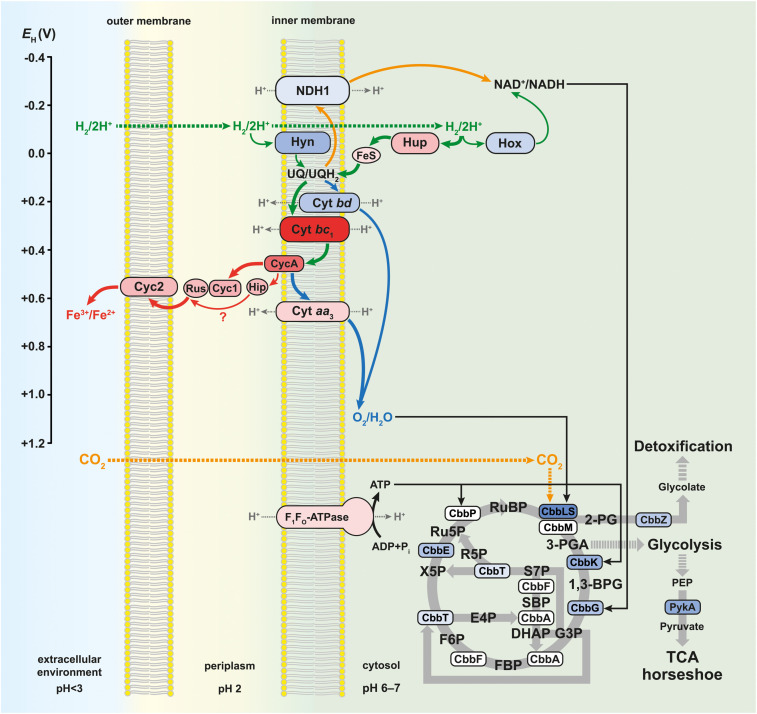

The schematic of the multi-omics approach used is shown in Figure 1A. This identified a total of 3,169 gene transcripts (98.4% coverage; a total of 3,219 coding sequences in At. ferrooxidans CCM 4253 genome) and 8,949 proteotypic (non-shared) peptides (Supplementary Table 1) representing 1,427 proteins (Supplementary Table 2), of which 1,412 proteins (46.2% coverage; a total of 3,059 protein-coding genes in At. ferrooxidans CCM 4253 genome) were quantified based on at least one proteotypic peptide in at least 50% measurements across the study. By comparing the anaerobic versus aerobic H2-oxidizing At. ferrooxidans cultures, a total of 371 DEGs (Supplementary Table 3) and 335 DEPs (Supplementary Table 4) were found. Of these, 203 DEGs and 181 DEPs were up-regulated during anaerobic growth on H2, while 168 DEGs and 154 DEPs were down-regulated (Figures 1B,C). Furthermore, 168 DEGs and 142 DEPs were uniquely up-regulated, and only 30 DEGs/DEPs showed mutual upregulation, while 126 DEGs and 116 DEPs were uniquely down-regulated and only 33 DEGs/DEPs exhibited mutual downregulation. Thus, the correlation between the DEGs and DEPs identified by each omics method was modest; 4.8% upregulation and 5.2% downregulation (Figure 1D), respectively. This relatively low overlap between mutually regulated genes and their products under the same growth conditions can be attributed to various factors, such as different half-lives and post transcription machinery (Haider and Pal, 2013). The most abundant proteins, representing more than 1% of the total protein in At. ferrooxidans, were the same for aerobic and anaerobic growth with H2. Among the most represented proteins were those encoded by the hup operon (small and large subunits of uptake [NiFe] group 2a hydrogenase involved in H2 oxidation), and the rus operon (cytochrome c552 and rusticyanin involved in electron transport during iron oxido-reduction, and two subunits of terminal aa3 oxidase involved in O2 reduction). Furthermore, outer membrane proteins (OmpA and Omp40, which increase cell hydrophobicity and help adhesion), and the GroEL/ES chaperonin system that functions as a protein folding cage, accounted for > 1% of total proteins (Supplementary Figure 1). The electron acceptor-dependent changes in the expression of gene cluster products (RNAs and proteins) that are involved in the energy metabolism of At. ferrooxidans growing on H2 are shown in Figure 2. The relative abundances of the energy metabolism proteins under both growth conditions are shown in Figure 3. Based on results obtained in this work, a model of aerobic and anaerobic metabolism of H2 connected with CO2 assimilation in the extremophile At. ferrooxidans is proposed (Figure 4).

FIGURE 1.

Multi-omics analysis of aerobically and anaerobically grown At. ferrooxidans cells with hydrogen as an electron donor. Experimental design including cultivation, next-generation sequencing, quantitative proteomics, and bioinformatic data analysis (A). Volcano plot representing all expressed genes (B). Volcano plot representing all identified proteins (C). Closed circles indicate gene transcripts and proteins that changed significantly (q < 0.05); colored circles indicate significant fold change (|log2 fc| > 1 for gene transcripts, and 0.58 for proteins, respectively). Venn diagram displays significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and proteins (DEPs) values (q < 0.05) with |log2 fc| > 1 for gene transcripts, and 0.58 for proteins, respectively (D).

FIGURE 2.

The heat map of products of energy metabolism-related gene clusters that were differentially expressed in aerobically and anaerobically grown At. ferrooxidans cells with hydrogen as an electron donor. Shown are only genes and proteins that changed significantly (q < 0.05) with absolute log2 fold change > 1 for gene transcripts and 0.58 for proteins.

FIGURE 3.

Relative abundances of energy metabolism proteins in aerobically and anaerobically grown At. ferrooxidans cells with hydrogen as an electron donor. Blue bars represent aerobic growth (electron acceptor: oxygen), and red bars represent anaerobic growth (electron acceptor: ferric iron). An asterisk indicates a significant change between the aerobic and anaerobic growth (|log2 fold change| > 0.58 and q < 0.05). Error bars are standard deviations of triplicate analyses.

FIGURE 4.

Model of aerobic and anaerobic metabolism of hydrogen connected with carbon dioxide assimilation in At. ferrooxidans. Solid green arrows indicate direct electron transfer, solid orange arrows indicate reverse electron transfer, and solid gray arrows indicate enzymatic reactions during the aerobic and anaerobic metabolism. Solid blue arrows indicate direct electron transfer during aerobic metabolism, while solid red arrows indicate direct electron transfer during anaerobic metabolism. The thickness of the colored arrows corresponds to the pathway significance according to the relative protein abundance in Figure 3. Dotted gray arrows indicate proton transfer, dotted green arrows indicate hydrogen influx, and dotted orange arrows indicate carbon dioxide influx. The color of proteins and multiprotein complexes corresponds to the log2 fold changes in Figure 2. The redox potential values (EH) for individual proteins and multiprotein complexes are referenced in the text. 2-PG, 2-phosphoglycolate; 3-PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; SBP, sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; X5P, xylulose 5-phosphate; Ru5P, ribulose 5-phosphate; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate; PEP, 2-phosphoenolpyruvate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Molecular Hydrogen Metabolism

Aerobic and anaerobic oxidation by acidophilic bacteria such as At. ferrooxidans contributes to the global H2 cycle and may promote microbial productivity in oligotrophic environments. The redox potentials (EH) of the H2/2H+ and O2/H2O couples are −118 mV (calculated using the Nernst equation) and +1,120 mV at pH 2 (Bird et al., 2011), respectively. To avoid ferric iron insolubility (at pH > 3), the iron oxidation and reduction occur on the outer membrane or periplasm of Acidithiobacillus spp., which have a similar pH to that of the acidic bathing liquors in which these obligate acidophiles thrive. The EH value of the Fe2+/Fe3+ couple in acidic, sulfate-rich solutions at pH 2.0 was measured to be +663 mV (Johnson et al., 2017). The net potential differences between H2 as electron donor and O2 or Fe3+ as electron acceptors are ∼1,238 and ∼781 mV, respectively. While the EH value of the Fe2+/Fe3+ varies with pH and whether one (or both) species of iron are complexed, it is always less electro-positive than the O2/H2O couple, inferring that anaerobic oxidation of H2 coupled to Fe3+ yields marginally less energy than oxidation coupled to O2. In addition, during aerobic growth, pH values remained steady (around 1.8), while slightly decreasing from 2.0 to 1.8 during anaerobic growth, which supported the theoretical equations and the formation of water under aerobic and protons and ferrous iron under anaerobic conditions, respectively. We have found all groups (1–4) of [NiFe] hydrogenases in the At. ferrooxidans CCM 4253 genome sequence, identical to those from the type strain (Valdés et al., 2008). However, our proteomic analysis revealed only the presence of three [NiFe] hydrogenases in At. ferrooxidans, namely group 1 Hyn, group 2 Hup, and group 3 Hox (Figure 3). The small subunit of Hyn (HynS) has a twin-arginine transport (TAT) signal sequence [ST]-R-R-x-F-L-K, it is transported across the membrane by the TAT system and is anchored to the membrane on the periplasmic side. The Hup and Hox have no signal for transport across the membrane, which makes them likely cytoplasmic enzymes. A comparison of protein abundance showed that H2 oxidation is predominantly ensured by the cytoplasmic Hup (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with earlier observations where 90% of the total hydrogenase activity was recovered from soluble fraction, while 12% of the total activity was found in the membrane fraction of At. ferrooxidans (Fischer et al., 1996). The hynS-isp1-isp2-hynL structural genes encode the inner-membrane respiratory H2-uptake [NiFe] group 1e hydrogenase (Isp-type), which is typically present in phototrophic and chemotrophic bacteria capable of respiratory sulfur oxidation and reduction. According to HydDB database, the group 1e-hydrogenase is bidirectional, O2-sensitive (some with a tolerance to microoxic conditions) enzyme thought to be involved in hydrogenotrophic respiration using sulfur as terminal electron acceptor (Søndergaard et al., 2016). The cluster also includes maturation-related genes, which are essential for respiratory hydrogenase complex formation. The structural genes hynS, isp2, hynL, and the maturation-related gene hypD2, were all significantly induced during aerobic growth with H2. At the protein level, only maturation related HynD and HynB2 were increased during aerobic H2 oxidation (Figure 2). Given the overall low abundance (Figure 3), it would be anticipated that the membrane-bound respiratory Hyn only complements H2 oxidation coupled to oxygen or ferric iron reduction. Transport of electrons from [NiFe] group 1–2 hydrogenases into the respiratory chain to quinones is assumed to be mediated by a protein carrying the [FeS] center (Islam et al., 2019). Therefore, the electrons derived from H2 oxidation in the active [NiFe] center of an enzyme are further transported up to the Ips2 subunit, [FeS]-binding protein (4Fe-4S ferredoxin-type), which transfers them to quinones in the cytoplasmic membrane (Figure 4). On the other hand, the main H2 oxidation pathway seems to be mediated by a soluble uptake Hup which was previously purified from At. ferrooxidans ATCC 19859 (Fischer et al., 1996). The enzyme consisting of two subunits (large of 64 kDa and small of 34 kDa) corresponds to alternative and sensory H2-uptake [NiFe] group 2a hydrogenase (Cyanobacteria-type), which is widespread among Cyanobacteria and aerobic soil bacteria. The group 2a hydrogenase is membrane-associated, unidirectional (some with high-affinity), O2-tolerant enzyme suggested to be involved in hydrogenotrophic respiration using O2 as the terminal electron acceptor (Søndergaard et al., 2016). The Hup reacted with methylene blue and other artificial electron acceptors, but not with NAD+, and has optimum activity at pH 9 and 49°C (Fischer et al., 1996). This cyanobacterial-like hydrogenase showed the characteristics of uptake [NiFe] hydrogenases as determined by EPR and FTIR (Schröder et al., 2007). The hupL-hupS structural genes encode the uptake [NiFe] group 2a hydrogenase. Similar to group 1e, the cluster contains maturation-related genes, in addition to transcriptional factor hupR and genes with unknown function. Hup showed about a 100-fold higher relative protein abundance compared to other hydrogenases in At. ferrooxidans growing on H2 under both growth conditions (Figure 3). Also, both subunits of Hup were among the most abundant proteins. The small subunit represented 2.5% (aerobic growth) and 1.4% (anaerobic growth) of total protein, while the large subunit represented 5.6% (aerobic growth) and 3.6% (anaerobic growth) of total protein (Supplementary Figure 1). In addition, gene loci with unknown function DN052_04105–04110 and DN052_04125–04130 were induced during anaerobic growth, as well as genes encoding the structural subunit and transcriptional regulator, hupL and hupR, respectively (Figure 2). Furthermore, the elevated levels of maturation proteins (HypB1, HypE, GmhA, HypC1, HypF, HybD), proteins with unknown functions (DN052_04090, DN052_04110, DN052_04115), iron-sulfur proteins (NifU and DN052_04130) were detected during anaerobic growth (Figure 2). There are two potential candidates of protein carrying the [FeS] center in the hup operon. The first candidate is the nifU gene, a locus DN052_04095, which encodes the Rieske protein with [2Fe-2S] iron-sulfur domain. Rieske proteins are components of cytochrome bc1 (proteobacteria) and b6f (cyanobacteria) complexes that are responsible for electron transfer in the respiratory chain (ten Brink et al., 2013). Another candidate is near the hupLS genes encoding the structural subunits, a locus DN052_04130, which encodes putative high potential iron-sulfur protein (HiPIP). HiPIPs are a specific class of high-redox potential [4Fe-4S] ferredoxins that are commonly found in various bacteria as periplasmic electron carriers between the bc1 complex and the reaction center or a terminal oxidase (Nouailler et al., 2006). One or both of these proteins are likely the missing link in the electron transfer between the H2 oxidation in the cytoplasm and the respiratory chain represented by the ubiquinone/ubiquinol (UQ/UQH2) pool in the cytoplasmic membrane. The ubiquinol molecule produced by the hydrogenases of the respiratory chain can diffuse within the membrane bilayer to the cytochrome ubiquinol oxidase or the cytochrome bc1 complex (Figure 4). The expression of the hoxF gene encoding the alpha subunit of cofactor-coupled bidirectional [NiFe] group 3b hydrogenase (NADP-coupled) was significantly increased during aerobic growth with H2 (Figure 2). The alpha subunit possesses a [4Fe-4S] ferredoxin domain that provides H2/H+ production. The group 3b hydrogenase is a cytosolic, bidirectional, O2-tolerant enzyme encoded in many diverse bacterial and archaeal phyla that was proposed to directly couple oxidation of NADPH to fermentative generation of H2. The reverse reaction may also occur. Some enzymes have been controversially proposed to harbor sulfhydrogenase activity (Søndergaard et al., 2016). At the protein level, however, only the beta subunit HoxH was detected whose low level was not significantly altered depending on the terminal electron acceptor (Figure 3). Group 3b hydrogenase may minorly oxidize H2 to form NAD(P)H, which can be further utilized, e.g., in the Calvin cycle (Figure 4). The reverse role of the group 3b hydrogenase could be NAD(P)+ recycling using protons or water and therefore serves as an electron sink under high reduction conditions (Valdés et al., 2008). None of the respiratory H2-evolving [NiFe] group 4 hydrogenase subunits were identified during either aerobic or anaerobic growth with H2. Non-hydrogenase catalytic subunit sequences were found in the hyfBCEFGI cluster (DN052_15040–15065) using an accurate classifier and a curated database of hydrogenases HydDB (Søndergaard et al., 2016). At. ferrooxidans thus probably has only three [NiFe] hydrogenases representing the groups 1e, 2a, and 3b. As At. ferrooxidans ATCC 21834 was shown to grow on formate when the substrate supply was growth limiting (Pronk et al., 1991), another role for the membrane-bound Hyf complex may involve the oxidation of formate (Valdés et al., 2008).

Molecular Oxygen Reduction

In this work, a significant increase in both the subunits I and II (CydA and CydB) of cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase was observed during aerobic growth with H2 (Figure 2). The bioenergetic function of cytochrome bd is to conserve energy in the form of ΔμH+, although the H+/e– ratio is one because the cytochrome bd does not pump protons. In addition to the generation of PMF, the bd-type oxygen reductase gives bacteria some other vital physiological functions. The apparent redox potentials of b558, b595, and d for cytochrome bd oxidase for E. coli at pH 7 were shown to be in the range of +176, +168, +258 mV, respectively. Furthermore, it was reported that these values are sensitive to pH, so they increase with decreasing pH (Borisov et al., 2011). None of the cytochrome bo3 ubiquinol oxidase subunits were identified during either aerobic or anaerobic growth with H2. On the other hand, the CoxC, CoxA, and CoxB subunits of aa3 cytochrome c oxidase were significantly increased during anaerobic growth with H2 (Figure 2). The a-type cytochromes in At. ferrooxidans also have pH-dependent redox potential of +725 mV and +610 mV at pH 3.2, and +500 mV and +420 mV at pH 7 (Ingledew and Cobley, 1980). The higher abundance of cytochrome aa3 oxidase in O2-free conditions was likely related to co-expression with other genes within the rus operon (Figure 2). Moreover, cytochrome aa3 may serve as a residual O2 scavenger to inhibit the degradation of O2-sensitive proteins and thus support anaerobic growth. The cytochrome aa3 subunits I and II represented the most abundant proteins under both aerobic (1.4 and 1.9% of total proteins, respectively) and anaerobic conditions (1.9 and 2.7%) in which their reductase function could be utilized (Supplementary Figure 1). By comparing the quantity of both terminal oxidases, the proportion of the aa3-type is much higher than that of the bd-type (Figure 3). We hypothesize that At. ferrooxidans reduces O2 to H2O in two parallel pathways during aerobic H2 oxidation. The first O2 reduction pathway includes cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase, which acquires electrons directly from the UQ/UQH2 pool. However, there is only one PMF-generating complex in this pathway, so less energy is conserved in the form of ATP and NADH. The second O2 reduction pathway includes cytochrome aa3 oxidase, which acquires electrons from the UQ/UQH2 pool via cytochrome bc1 complex by cytochrome c4. There are already two PMF-generating complexes in this pathway and therefore provide more energy (Figure 4). At. ferrooxidans genome sequence contains two operons encoding the cytochrome bc1 complex (petI–II). Products of the petI operon are known to be important in reverse electron flow to NADH-UQ oxidoreductase (NDH1) in aerobic Fe2+ oxidation, and petII products are likely to complement electron transfer from UQ/UQH2 pool to terminal oxidase in aerobic RISCs oxidation (Quatrini et al., 2009). By comparing the quantity of both cytochrome bc1 complexes during aerobic growth with H2, the proportion of the bc1 complex I is higher than that of the bc1 complex II, which is almost undetectable (Figure 2). Thus, it is likely that electrons from the UQ/UQH2 pool are transported to the terminal aa3-type oxidase via bc1 complex I (PetA1B1C1) by membrane-associated cytochrome c4 (CycA1). It would mean that the bc1 complex I can transfer electrons even in a direct flow to the terminal oxidase following the redox potential gradient, and not in reverse flow to the NDH1 complex, when the electron donor is H2.

Ferric Iron Reduction

In this work, almost all the rus operon products were significantly elevated at the protein level in At. ferrooxidans during anaerobic growth with H2 coupled to Fe3+ reduction (Figure 2). Significant changes were observed in the synthesis of rusticyanin, Cyc1A, and Cyc2A. Rusticyanin and Cyc1A represented the most abundant proteins in aerobically (3.3 and 2.1% of total proteins, respectively) and anaerobically (6.4 and 4.6%) grown At. ferrooxidans cells (Supplementary Figure 1). High level of soluble acid-stable 28 kDa c-type cytochrome was observed in At. ferriphilus JCM 7811 grown anaerobically on H2 coupled to Fe3+ reduction. Also, the presence of iso-rusticyanin in cells of this related bacterium grown anaerobically on H2 was detected by immunostaining (Ohmura et al., 2002). The At. ferrooxidans genome sequence contains a two-gene cluster DN052_01245–DN052_01250 encoding c-type cytochromes that are homologs of the Cyc1A and Cyc2A. The new c-type cytochromes (Cyc1B and Cyc2B) have been discovered in At. ferrooxidansT during anaerobic growth with S0 coupled to Fe3+ reduction. Their relative protein abundances under anaerobic conditions were even higher than the levels of their homologs encoded by the rus operon (Norris et al., 2018). In this work, both Cyc1B and Cyc2B were significantly increased during anaerobic growth of At. ferrooxidans with H2 coupled to Fe3+ reduction (Figure 2). However, their relative abundances were considerably lower compared to Cyc2A and especially Cyc1A (Figure 3). The significance of the role of these homologs in respiratory Fe3+ reduction may be related to specific strains, substrate, or longer adaptation, though cytochromes Cyc2 and Cyc1 seem to play an essential role in the electron transport and mechanism of Fe3+ reduction. The EH of c-type cytochromes from At. ferrooxidans typically are +560 mV Cyc2 (pH 4.8), +385 and +485 mV Cyc1 (pH 3), +510 and +430 mV CycA (pH 4), and +680 mV for blue-copper protein rusticyanin (pH 3.2) (Bird et al., 2011). Moreover, the formation of a complex between rusticyanin and Cyc1 decreases the rusticyanin redox potential by more than 100 mV, which facilitates electron transfer (Roger et al., 2012). Thus, the electrons needed for Fe3+ reduction are delivered via a cascade of periplasmic and membrane-associated electron carriers. Periplasmic rusticyanin forming a complex with Cyc1 receives electrons from the inner membrane-anchored cytochrome CycA and transmits them to outer membrane cytochrome Cyc2. Extracellular Fe3+ is then reduced from the outside of the outer membrane by Cyc2 (Figure 4). All homologs Cyc1 and Cyc2 are considered, i.e., variants A and B. Cytochrome c4 (CycA) accepts electrons from the inner-membrane cytochrome bc1 complex, which transfers them from the UQ/UQH2 pool. During anaerobic growth with H2, the complete petII operon was strongly induced at the level of transcription and protein synthesis (Figure 2). On the other hand, a significant increase in the expression of two genes of the petI operon was also detected. By comparing the protein quantity of both cytochrome bc1 complexes during anaerobic growth on H2, the proportion of the bc1 complex II is much higher than that of the bc1 complex I (Figure 3). The electrons appear to be transported from the UQ/UQH2 pool to the bcl complex II (PetA2B2C2), which further transfers them to CycA2 (Figure 4). Nevertheless, a slight involvement of the bc1 complex I (PetA1B1C1) and CycA1 in electron transport might be expected, as they are also present in At. ferrooxidans during anaerobic H2 oxidation (Figure 3), which is consistent with previous results in the anaerobic S0 oxidation (Kucera et al., 2016a). The involvement of high potential iron-sulfur protein (Hip, formerly Iro) in electron transport remains an issue. The Hip is part of the petII operon and was significantly increased during anaerobic H2 oxidation coupled to Fe3+ reduction (Figure 2), and also during anaerobic S0 oxidation coupled to Fe3+ reduction (Kucera et al., 2016a). The functional form of Hip contains a redox-active [4Fe-4S] cluster, which is usually sensitive to O2. This feature may predetermine its function in an anaerobic respiration process. The redox potential of Hip decreases linearly depending on pH in the range 3.5–5, but remains constant at lower and higher pH, and is +550 mV at pH 2 (Bruscella et al., 2005). The same pH dependence of redox potential was observed for rusticyanin (Haladjian et al., 1993) and Cyc1 (Haladjian et al., 1994). From their properties, it is possible that Hip and rusticyanin/Cyc1 function interchangeably to reduce terminal Fe3+ reductase in this bacterium (Figure 4). However, the role of Hip in the mechanism of anaerobic H2 oxidation in At. ferrooxidans may not be essential, due to the relatively non-specific electron transfer and comparison of its quantity to rusticyanin and other c-type cytochromes (Figure 3).

Energy Conservation

Because the EH values of UQ/UQH2 and NAD+/NADH are +110 and –320 mV, respectively, at cytoplasmic pH values (pH 6–7), some electrons coming from substrate oxidation are pushed uphill against the unfavorable redox potential. This reverse electron flow is driven by the PMF (Bird et al., 2011). Three subunits NuoL, NuoF, and NuoC of the NDH1 were induced when At. ferrooxidans grew aerobically with H2 (Figure 2). To date, there is no evidence that the same mechanism of reverse flow for NADH regeneration is the case for both aerobic and anaerobic respiration. On the other hand, many autotrophic bacteria use multiple electron donors and acceptors, suggesting the existence of a universal pathway for NADH regeneration through uphill transfer connecting to each respiratory chain (Ohmura et al., 2002). Our data support this hypothesis, with the finding of the same level of induction of the majority (10 of 14) of NDH1 subunits when At. ferrooxidans used H2 as an electron donor and either O2 or Fe3+ as electron acceptor (Figure 3). On the other hand, the upregulation of a few genes encoding the NDH1 complex under aerobic growth was likely related to the upregulation of other genes of the cbb operons involved in CO2 assimilation (discussed below), which require reducing equivalents such as NADH. The higher energy gain when the terminal acceptor is O2 may lead to an increased reduction of NAD+ to NADH, which allows a higher rate of CO2 assimilation resulting in higher biomass during aerobic growth. Also, the ubiquinone/menaquinone biosynthesis C-methyltransferase (UbiE) was more abundant under aerobic conditions, whereas 2-octaprenyl-6-methoxyphenyl hydroxylase (UbiH) was more abundant under anaerobic conditions (Figure 2), both of which are involved in the ubiquinone biosynthesis. Although UbiE and UbiH altered in protein quantity depending on electron acceptor, the majority of proteins in this pathway were constitutively synthesized (Figure 3) to provide the required ubiquinone pool for both aerobic and anaerobic respiration (Figure 4). At. ferrooxidans conserves energy by producing ATP from ADP via F1FO ATP synthase in the presence of a proton gradient (Ingledew, 1982). In this study, significant abundances in epsilon subunit (AtpC) of the F1 portion and subunit b (AtpF) of the FO portion were found during anaerobic growth of At. ferrooxidans on H2 (Figure 3). In addition, genes atpE and atpB encoding subunits a and c of FO portion, respectively, were increased at their transcript levels (Figure 2).

Carbon Metabolism

Chemoautotrophic acidophilic bacteria use different pathways for inorganic carbon (Ci) assimilation to produce complex organic compounds. Five operons (cbb1-5) in the At. ferrooxidans genome, encoding enzymes and structural proteins involved in Ci assimilation via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) pathway, have been described (Esparza et al., 2010, 2019). In this work, we investigated changes in the expression of all five cbb operons during aerobic and anaerobic growth of At. ferrooxidans with H2 (Figure 2). Interestingly, although the concentration of CO2 was greater under anaerobic conditions, we detected an upregulation of cbb genes under aerobic conditions, which may indicate not only their CO2-depending regulation, but also an impact of other factors, such as O2 concentration. A key enzyme in the CBB pathway is cytoplasmic ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco). Of all Rubisco forms, a form II (CbbM) was the most abundant under both growth conditions, although its abundance did not change significantly (Figure 3). The form II seems to be synthesized constitutively, independent of O2 concentration. Rubisco form II has a weak affinity for CO2 (Esparza et al., 2019), which might explain its higher abundance compared to IAc and IAq. Nevertheless, a large subunit of the form IAc (CbbL1) and both subunits of the form IAq (CbbL2S2) were significantly more abundant during aerobic growth of At. ferrooxidans with H2 (Figure 2). Both Rubisco IAc and IAq forms appear to be O2 dependent. As carboxylation and oxidation of RuBP coincide, both reactions may compete in the same active place. Enzymes passing the carbon from 3-phosphoglycerate produced by Rubisco via the CBB and glycolysis pathways to pyruvate and glycogen metabolism pathways are encoded by the cbb3 operon (Esparza et al., 2019), the expression profile of which is shown in Figure 2. The initial Ci assimilation pathways during H2 oxidation are proposed in Figure 4.

Conclusion

We provide the first overall insight into the mechanisms employed by acidithiobacilli to metabolize hydrogen in low-pH aerobic and anaerobic environments. The model presented here describes the molecular hydrogen metabolism and the energy conservation associated with the assimilation of inorganic carbon. This study is a fundamental step in identifying elements of metabolic pathways when At. ferrooxidans utilizes hydrogen as an electron donor and may further be a starting point for characterizing the physiology of hydrogen metabolism and ferric iron reduction in other mesophilic acidophiles.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The transcriptomic data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under reference number GSE154815. The mass spectrometry proteomics data are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD020361.

Author Contributions

JK and DBJ designed the study. JK and EP conducted the laboratory experiments. JL performed RNA sequencing and data analysis. KM performed the LC-MS/MS analysis. PB performed the analysis of MS/MS data. JK, MM, and OJ were involved in data analysis and biological interpretation of the results. JK prepared the manuscript. SH, EP, and DBJ edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Martina Zapletalova for her collaboration on data analysis using R packages. The current address of EP and DBJ (along with the Bangor University) is Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Coventry University, Coventry, United Kingdom.

Funding. CIISB research infrastructure project LM2018127 funded by MEYS CR was gratefully acknowledged for the financial support of the measurements at the CEITEC Proteomics Core Facility.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.610836/full#supplementary-material

Proteins representing more than 1% of the total protein in hydrogen-oxidizing Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans cells. Blue bars represent aerobic growth (electron acceptor: oxygen), and red bars represent anaerobic growth (electron acceptor: ferric iron). Labels show percentages of total protein in each growth condition. Error bars are standard deviations of triplicate analyses.

List of all quantified peptides in DIA-MS proteomics analysis.

List of all quantified proteins in DIA-MS proteomics analysis.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in aerobically and anaerobically grown At. ferrooxidans cells with hydrogen as an electron donor.

Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in aerobically and anaerobically grown At. ferrooxidans cells with hydrogen as an electron donor.

References

- Amils R. (2015). Technological challenges to understanding the microbial ecology of deep subsurface ecosystems. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 7 9–10. 10.1111/1758-2229.12219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong F. A., Albracht S. P. (2005). [NiFe]-hydrogenases: spectroscopic and electrochemical definition of reactions and intermediates. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 363 937–954. 10.1098/rsta.2004.1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnoud A., Chourey K., Hettich R. L., De Bruijn I., Andersson A. F., Leupin O. X., et al. (2016). Reconstructing a hydrogen-driven microbial metabolic network in Opalinus Clay rock. Nat. Commun. 7:12770. 10.1038/ncomms12770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister A., Rettberg P., Flemming H.-C. C. (2014). Growth of the acidophilic iron-sulfur bacterium Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans under Mars-like geochemical conditions. Planet. Space Sci. 98 205–215. 10.1016/j.pss.2013.09.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bird L. J., Bonnefoy V., Newman D. K. (2011). Bioenergetic challenges of microbial iron metabolisms. Trends Microbiol. 19 330–340. 10.1016/j.tim.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. C., D’Hondt S., Spivack A. J., Kingsley R. H. (2007). Radiolytic hydrogen and microbial respiration in subsurface sediments. Astrobiology 7 951–970. 10.1089/ast.2007.0150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy V., Grail B. M., Johnson D. B. (2018). Salt stress-induced loss of iron oxidoreduction activities and reacquisition of that phenotype depend on rus operon transcription in Acidithiobacillus ferridurans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84:e02795-17. 10.1128/aem.02795-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisov V. B., Gennis R. B., Hemp J., Verkhovsky M. I. (2011). The cytochrome bd respiratory oxygen reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807 1398–1413. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchal P., Roumeliotis T., Hrstka R., Nenutil R., Vojtesek B., Garbis S. D. (2009). Biomarker discovery in low-grade breast cancer using isobaric stable isotope tags and two-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (iTRAQ-2DLC-MS/MS) based quantitative proteomic analysis. J. Proteome Res. 8 362–373. 10.1021/pr800622b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasseur G., Levican G., Bonnefoy V., Holmes D., Jedlicki E., Lemesle-Meunier D. (2004). Apparent redundancy of electron transfer pathways via bc1 complexes and terminal oxidases in the extremophilic chemolithoautotrophic Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1656 114–126. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruscella P., Cassagnaud L., Ratouchniak J., Brasseur G., Lojou E., Amils R., et al. (2005). The HiPIP from the acidophilic Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans is correctly processed and translocated in Escherichia coli, in spite of the periplasm pH difference between these two micro-organisms. Microbiology 151 1421–1431. 10.1099/mic.0.27476-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell B., Rood J., Singer E. (2017). BBMerge – accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLoS One 12:e0185056. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0185056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carere C. R., Hards K., Houghton K. M., Power J. F., McDonald B., Collet C., et al. (2017). Mixotrophy drives niche expansion of verrucomicrobial methanotrophs. ISME J. 11 2599–2610. 10.1038/ismej.2017.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle F. H., O’Neill K., Bradley P. M., Methé B. A., Ciufo S. A., Knobel L. L., et al. (2002). A hydrogen-based subsurface microbial community dominated by methanogens. Nature 415 312–315. 10.1038/415312a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B. C., Hunter C. L., Liu Y., Schilling B., Rosenberger G., Bader S. L., et al. (2017). Multi-laboratory assessment of reproducibility, qualitative and quantitative performance of SWATH-mass spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 8:291. 10.1038/s41467-017-00249-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett C. M., Ingledew W. J. (1987). Is Fe3+/2+ cycling an intermediate in sulphur oxidation by Fe2+-grown Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 41 1–6. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1987.tb02131.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drobner E., Huber H., Stetter K., Mikrobiologie L., Regensburg U. (1990). Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, a facultative hydrogen oxidizer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56 2922–2923. 10.1128/aem.56.9.2922-2923.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza M., Cárdenas J. P., Bowien B., Jedlicki E., Holmes D. S. (2010). Genes and pathways for CO2 fixation in the obligate, chemolithoautotrophic acidophile, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, carbon fixation in A. ferrooxidans. BMC Microbiol. 10:229. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza M., Jedlicki E., González C., Dopson M., Holmes D. S. (2019). Effect of CO2 concentration on uptake and assimilation of inorganic carbon in the extreme acidophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Front. Microbiol. 10:603. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J., Quentmeier A., Kostka S., Kraft R., Friedrich C. G. (1996). Purification and characterization of the hydrogenase from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Arch. Microbiol. 165 289–296. 10.1007/s002030050329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafidh S., Potěšil D., Müller K., Fíla J., Michailidis C., Herrmannová A., et al. (2018). Dynamics of the pollen sequestrome defined by subcellular coupled omics. Plant Physiol. 178 258–282. 10.1104/pp.18.00648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider S., Pal R. (2013). Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data. Curr. Genomics 14 91–110. 10.2174/1389202911314020003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haladjian J., Bianco P., Nunzi F., Bruschi M. (1994). A permselective-membrane electrode for the electrochemical study of redox proteins. Application to cytochrome c552 from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Anal. Chim. Acta 289 15–20. 10.1016/0003-2670(94)80002-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haladjian J., Bruschi M., Nunzi F., Bianco P. (1993). Electron-transfer reaction of rusticyanin, a “blue”-copper protein from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, at modified gold electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 352 329–335. 10.1016/0022-0728(93)80276-N [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich S., Johnson D. B. (2013). Aerobic and anaerobic oxidation of hydrogen by acidophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 349 40–45. 10.1111/1574-6968.12290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber G., Drobner E., Huber H., Stetter K. O. (1992). Growth by aerobic oxidation of molecular hydrogen in archaea —a metabolic property so far unknown for this domain. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 15 502–504. 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80108-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingledew W. J., Cobley J. G. (1980). A potentiometric and kinetic study on the respiratory chain of ferrous-iron-grown Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 590 141–158. 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90020-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingledew W. J. J. (1982). Thiobacillus ferrooxidans the bioenergetics of an acidophilic chemolithotroph. BBA Rev. Bioenerg. 683 89–117. 10.1016/0304-4173(82)90007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z. F., Cordero P. R. F., Greening C. (2019). Putative iron-sulfur proteins are required for hydrogen consumption and enhance survival of mycobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 10:2749. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z. F., Welsh C., Bayly K., Grinter R., Southam G., Gagen E. J., et al. (2020). A widely distributed hydrogenase oxidises atmospheric H2 during bacterial growth. ISME J. 14 2649–2658. 10.1038/s41396-020-0713-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janacova L., Faktor J., Capkova L., Paralova V., Pospisilova A., Podhorec J., et al. (2020). SWATH-MS analysis of FFPE tissues identifies stathmin as a potential marker of endometrial cancer in patients exposed to tamoxifen. J. Proteome Res. 19 2617–2630. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. B. (2012). Geomicrobiology of extremely acidic subsurface environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 81 2–12. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01293.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. B. (2015). Biomining goes underground. Nat. Geosci. 8 165–166. 10.1038/ngeo2384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. B., Hallberg K. B. (2007). “Techniques for detecting and identifying acidophilic mineral-oxidizing microorganisms,” in Biomining, eds Rawlings D. E., Johnson D. B. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag; ), 237–261. 10.1007/978-3-540-34911-2_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. B., Hedrich S., Pakostova E. (2017). Indirect redox transformations of iron, copper, and chromium catalyzed by extremely acidophilic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 8:211. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera J., Bouchal P., Cerna H., Potesil D., Janiczek O., Zdrahal Z., et al. (2012). Kinetics of anaerobic elemental sulfur oxidation by ferric iron in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and protein identification by comparative 2-DE-MS/MS. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 101 561–573. 10.1007/s10482-011-9670-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera J., Pakostova E., Lochman J., Janiczek O., Mandl M. (2016a). Are there multiple mechanisms of anaerobic sulfur oxidation with ferric iron in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans? Res. Microbiol. 167 357–366. 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera J., Sedo O., Potesil D., Janiczek O., Zdrahal Z., Mandl M. (2016b). Comparative proteomic analysis of sulfur-oxidizing Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans CCM 4253 cultures having lost the ability to couple anaerobic elemental sulfur oxidation with ferric iron reduction. Res. Microbiol. 167 587–594. 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. 10.1186/S13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz W., Ogata H., Rüdiger O., Reijerse E. (2014). Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 114 4081–4148. 10.1021/cr4005814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew L. E., Ellison E. T., McCollom T. M., Trainor T. P., Templeton A. S. (2013). Hydrogen generation from low-temperature water–rock reactions. Nat. Geosci. 6 478–484. 10.1038/ngeo1825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S., Parnell J. (2014). Weighing the deep continental biosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 87 113–120. 10.1111/1574-6941.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo H., Chen Q., Du J., Tang L., Qin F., Miao B., et al. (2011). Ferric reductase activity of the ArsH protein from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21 464–469. 10.4014/jmb.1101.01020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi S. S., Schmitz R. A., Pol A., Berben T., Jetten M. S. M., Op den Camp H. J. M. (2019). The acidophilic methanotroph Methylacidimicrobium tartarophylax 4AC grows as autotroph on H2 under microoxic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 10:2352. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M., Anders S., Lawrence M., Aboyoun P., Pages H., Gentleman R. (2009). ShortRead: a bioconductor package for input, quality assessment and exploration of high-throughput sequence data. Bioinformatics 25 2607–2608. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris P. R., Falagán C., Moya-Beltrán A., Castro M., Quatrini R., Johnson D. B. (2020). Acidithiobacillus ferrianus sp. nov.: an ancestral extremely acidophilic and facultatively anaerobic chemolithoautotroph. Extremophiles 24 329–337. 10.1007/s00792-020-01157-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris P. R., Laigle L., Slade S. (2018). Cytochromes in anaerobic growth of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Microbiology 164 383–394. 10.1099/mic.0.000616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouailler M., Bruscella P., Lojou E., Lebrun R., Bonnefoy V., Guerlesquin F. (2006). Structural analysis of the HiPIP from the acidophilic bacteria: Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Extremophiles 10 191–198. 10.1007/s00792-005-0486-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmura N., Sasaki K., Matsumoto N., Saiki H. (2002). Anaerobic respiration using Fe3+, S0, and H2 in the chemolithoautotrophic bacterium Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Bacteriol. 184 2081–2087. 10.1128/JB.184.8.2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio H., Mangold S., Denis Y., Ñancucheo I., Esparza M., Johnson D. B., et al. (2013). Anaerobic sulfur metabolism coupled to dissimilatory iron reduction in the extremophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 2172–2181. 10.1128/AEM.03057-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk J. T., Meijer W. M., Hazeu W., Van Dijken J. P., Bos P., Kuenen J. G. (1991). Growth of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans on formic acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57 2057–2062. 10.1128/aem.57.7.2057-2062.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente-Sánchez F., Arce-Rodríguez A., Oggerin M., García-Villadangos M., Moreno-Paz M., Blanco Y., et al. (2018). Viable cyanobacteria in the deep continental subsurface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115 10702. 10.1073/PNAS.1808176115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente-Sánchez F., Moreno-Paz M., Rivas L. A., Cruz-Gil P., García-Villadangos M., Gómez M. J., et al. (2014). Deep subsurface sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in the iberian pyrite belt revealed through geochemistry and molecular biomarkers. Geobiology 12 34–47. 10.1111/gbi.12065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatrini R., Appia-Ayme C., Denis Y., Jedlicki E., Holmes D. S., Bonnefoy V. (2009). Extending the models for iron and sulfur oxidation in the extreme acidophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. BMC Genomics 10:394. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger M., Castelle C., Guiral M., Infossi P., Lojou E., Giudici-Orticoni M.-T., et al. (2012). Mineral respiration under extreme acidic conditions: from a supramolecular organization to a molecular adaptation in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40 1324–1329. 10.1042/BST20120141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz R. A., Pol A., Mohammadi S. S., Hogendoorn C., van Gelder A. H., Jetten M. S. M., et al. (2020). The thermoacidophilic methanotroph Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV oxidizes subatmospheric H2 with a high-affinity, membrane-associated [NiFe] hydrogenase. ISME J. 14 1223–1232. 10.1038/s41396-020-0609-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder O., Bleijlevens B., de Jongh T. E., Chen Z., Li T., Fischer J., et al. (2007). Characterization of a cyanobacterial-like uptake [NiFe] hydrogenase: EPR and FTIR spectroscopic studies of the enzyme from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 12 212–233. 10.1007/s00775-006-0185-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søndergaard D., Pedersen C. N. S., Greening C. (2016). HydDB: a web tool for hydrogenase classification and analysis. Sci. Rep. 6 1–8. 10.1038/srep34212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stejskal K., Potěšil D., Zdráhal Z. (2013). Suppression of peptide sample losses in autosampler vials. J. Proteome Res. 12 3057–3062. 10.1021/pr400183v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens T. (1997). Lithoautotrophy in the subsurface. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20 327–337. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00318.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stookey L. L. (1970). Ferrozine—a new spectrophotometric reagent for iron. Anal. Chem. 42 779–781. 10.1021/ac60289a016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio T., Taha T. M., Takeuchi F. (2009). Ferrous iron production mediated by tetrathionate hydrolase in tetrathionate-, sulfur-, and iron-grown Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 Cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73 1381–1386. 10.1271/bbb.90036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Brink F., Schoepp-Cothenet B., van Lis R., Nitschke W., Baymann F. (2013). Multiple Rieske/cytb complexes in a single organism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg 1827 1392–1406. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y., Xu Y., Wang X., Christie P. (2019). Function of biohydrogen metabolism and related microbial communities in environmental bioremediation. Front. Microbiol. 10:106. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdés J., Pedroso I., Quatrini R., Dodson R. J., Tettelin H., Blake R., et al. (2008). Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans metabolism: from genome sequence to industrial applications. BMC Genomics 9:597. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignais P. M., Billoud B. (2007). Occurrence, classification, and biological function of hydrogenases: an overview. Chem. Rev. 107 4206–4272. 10.1021/cr050196r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proteins representing more than 1% of the total protein in hydrogen-oxidizing Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans cells. Blue bars represent aerobic growth (electron acceptor: oxygen), and red bars represent anaerobic growth (electron acceptor: ferric iron). Labels show percentages of total protein in each growth condition. Error bars are standard deviations of triplicate analyses.

List of all quantified peptides in DIA-MS proteomics analysis.

List of all quantified proteins in DIA-MS proteomics analysis.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in aerobically and anaerobically grown At. ferrooxidans cells with hydrogen as an electron donor.

Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in aerobically and anaerobically grown At. ferrooxidans cells with hydrogen as an electron donor.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The transcriptomic data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under reference number GSE154815. The mass spectrometry proteomics data are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD020361.