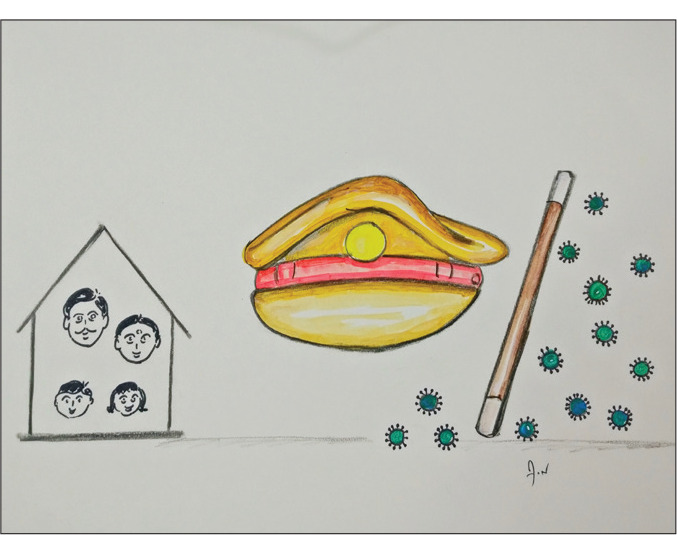

India reported the first case of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) on January 30, 2020. The government, since then has advocated wearing masks, physical distancing, avoiding public gathering, shutting down malls and theatres, isolation of positive cases, and quarantine of high-risk individuals as major preventive measures against COVID-19. Police were among the first responders to the COVID-19 disaster and are popularly listed among the “corona warriors,” along with health care personnel.

Police personnel in India are generally trained in dealing with natural and man-made disasters, though pandemic control is not emphasized as a subject during the training of the police.1 Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic required many police personnel to assume responsibility for the emergencies that were not part of their regular work profile.1, 2 The primary responsibility of implementing the lockdown through restricting public movement and ensuring physical distancing was shouldered by the police force during the pandemic, through the enforcement of the Epidemic Disease Act, 1987, and the Disaster Management Act, 2005.1 Police personnel was mobilized for a variety of tasks—to monitor check posts, monitor COVID-19 infection hotspots, and ensure lockdown as well as containment. In addition to this, police personnel also carried out a variety of unconventional duties, including creating social awareness, clarifying fake news, daily inspection of people in isolation or quarantine, assisting the health department in contact tracing activities, helping migrant workers to enter shelters, and helping the needy persons to access medical and other essential services.3, 4

Lack of awareness and specific knowledge of COVID-19 prevention and inadequate or inappropriate use of personal protective gear like mask and gloves substantially increase the risk of exposure to COVID-19 among police personnel.1 Table 1 shows the impact of COVID-19 on police personnel in India and Table 2 shows the infection rate in the police force in comparison to the general population as of August 31, 2020.5–7 It appears that police personnel are 8.78 times more likely to get affected by COVID-19 compared to the general population. In order to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19, the police departments have made risk mitigation plans like modifications in their human resource allotment (working with a small team, desk job for the vulnerable population rather than fieldwork) and use of technology in the services.1, 2, 4, 8

Table 1. The Impact of COVID-19 on Indian Police Personnel (as on August 31, 2020).

| Number of police personnel who tested positive | 71,832 | |

| Number of police personnel quarantined | 25,013 | |

| Number of police personnel who died | 428 | |

| Number of police personnel injured in attacks | 260 | |

| Top five states/division (personnel tested positive) | Maharashtra | 14,792 |

| Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) | 7,144 | |

| Telangana | 5,684 | |

| Border Security Force (BSF) | 4,983 | |

| West Bengal | 4,500 | |

| Top five states/division (personnel quarantined) | Maharashtra | 8,000 |

| Border Security Force (BSF) | 7,981 | |

| Madhya Pradesh | 2,000 | |

| Uttarakhand | 1,970 | |

| Kerala | 1,166 | |

Source: Indian Police Foundation website.6

Table 2. The Infection Rate in the Police Force in Comparison to the General Population (as on August 31, 2020).

| India | Indian Police Force | |

| Total population | 1,382,341,425 | 3,035,632 |

| Total cases reported | 3,679,411 | 71,832 |

| % of the population affected | 0.27 | 2.37 |

Sources: Indian Police Foundation website6 and Worldometer website.13,14

The unconventional responsibilities, demanding working conditions, and the ambiguity in the role of the police may result in job stress and burnout and have been established in earlier studies as a source of occupational stress among Indian police personnel.9, 10 The concern about being infected from the community and workplace may also be a potential source of fear among police personnel.1 Furthermore, concerns about carrying the infection to the family members may also be a source of psychological distress. Additionally, fear of quarantine and social stigma are possible causes of distress. This can result in a greater likelihood of police personnel developing a range of psychological problems such as burnout, emotional disturbances, psychological distress, sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression, substance use, and post-traumatic stress disorder.11 As per a recent online survey in which 102 police personnel of Maharashtra police department participated, 50% of the respondents had mental disturbance due to fear of the COVID-19 virus, whereas 32.4% reported being under stress due to multiple reasons at the workplace.12 There are sporadic incidents of suicide by police personnel associated with the fear of catching COVID-19.13, 14 In addition to increased workload and exposure to infection with coronavirus, police personnel, when trying to maintain law and order, are not uncommonly exposed to aggressive assaults by the public. Overall, since the COVID-19 crisis started, about 260 policemen have been injured in various incidents throughout the country.5 Such incidents pose a significant concern about their protection at work. This not only diminishes their morale but can also lead to significant psychological distress.

The COVID-19 crisis has undoubtedly impacted law enforcement practices across India. Therefore, the need of the hour is to pay attention to the psychological wellbeing of the police personnel. The first step towards this could be to raise awareness among them about mental health problems. It may be helpful to establish peer support networks within the police department to recognize and address their psychological problems. Because of high workload and stress, programs that target positive coping skills and building resilience can mitigate psychological distress. Training in relaxation practices such as deep breathing, meditation, or yoga can serve as methods to improve police personnel’s mental health and help them to cope with stress positively.11 Those police personnel who work away from their homes or undergo quarantine should be encouraged to maintain regular communication with the families through audio/video modalities to strengthen their primary system of support. In addition to ensuring adequate strategies for infection control and access to timely and affordable treatment, it may be advisable to establish facilities through telephone helplines or video consultation to provide psychological support. Police personnel with pre-existing psychiatric illnesses may be vulnerable to a worsening of those problems or developing new symptoms such as anxiety or depression. Timely referrals to seek psychiatric help for severe psychological symptoms should be encouraged.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Telangana State Police. Reference Handbook for Covid-19 Policing: Telangana State Police. Indian Police Foundation, https://www.policefoundationindia.org/images/resources/pdf/Reference_Handbook_for_Covid-19_Policing.pdf (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerala Police. COVID 19 standard operating procedure for day to day policing. Indian Police Foundation, https://www.policefoundationindia.org/images/resources/pdf/COVID_19_SoP.pdf (2020, accessed August 4, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haryana Police. Haryana police COVID-19 response. Indian Police Foundation, https://www.policefoundationindia.org/images/resources/pdf/Haryana_Police_COVID-19_Response-compressed.pdf (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assam Police. The new dimensions in policing: The case of Assam police as frontline anti-COVID workers. Indian Police Foundation, https://www.policefoundationindia.org/images/resources/pdf/Assam_Police_as_Frontline_anti-Covid_Workers.pdf (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Indian Police Foundation. COVID-19 resources: Indian Police Foundation. Indian Police Foundation; https://www.policefoundationindia.org/covid-19-resources (2020, accessed August 31, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worldometer. Coronavirus cases. Worldometer; 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/? (2020, accessed August 31, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worldometer. India population 2020. Worldometer, https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/india-population/ (2020, accessed August 31, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tripathi S. Health of police personnel in COVID times challenges and solutions: Maharashtra COVID-19 resources. Indian Police Foundation, https://www.policefoundationindia.org/images/resources/pdf/HEALTH_OF_POLICE_IN_COVID_TIMES_final.pdf (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank J, Lambert EG, Qureshi H. Examining police officer work stress using the job demands–resources model. J Contemp Crim Justice; 2017; 33: 348–367. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Kar SK. Sources of occupational stress in the police personnel of North India: An exploratory study. Indian J Occup Environ Med; 2015; 19: 56–60. http://www.ijoem.com/text.asp?2015/19/1/56/157012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stogner J, Miller BL, McLean K. Police stress, mental health, and resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Crim Justice. Epub ahead of print; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09548-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kokane PP, Maurya P, Muhammad M. Understanding the Incidence of COVID-19 among the police force in Maharashtra through a mixed approach. medRxiv. Epub ahead of print; 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.06.11.20125104. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raina M. Coronavirus outbreak: Covid-19 fear suicide in CRPF. Telegraph India, https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/coronavirus-outbreak-covid-19-fear-suicide-in-crpf/cid/1772507 (2020, accessed August 4, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy YM. Cop’s suicide adds to COVID fear. Bangalore Mirror, https://bangaloremirror.indiatimes.com/bangalore/others/cops-suicide-adds-to-covid-fear/articleshow/76539287.cms (2020, accessed August 4, 2020).